Abstract

Microcosm dental plaques were grown from an inoculum of human saliva in a constant-depth film fermentor. The inoculum contained four tetracycline-resistant streptococcal species, each of which contained a Tn916-like element. This element was shown to transfer to other streptococci both in filter-mating experiments and within the biofilms in the fermentor.

Tetracyclines are used for the treatment of periodontal disease (15). However, resistance to the drugs limits their usefulness. The most widespread resistance gene is tet(M), usually found on conjugative transposons (cTn) of the Tn916/Tn1545 family (2). Transfer of Tn916-mediated tetracycline resistance (Tetr) between oral streptococci during filter-mating experiments has been observed (6, 7). Furthermore, the cTn Tn5397 can transfer from a nonoral organism (Bacillus subtilis) to oral streptococci in a microcosm dental plaque (13). Tn916-like elements are present within the oral microflora (1, 3, 6, 8), and in this paper we show that they transfer Tetr not only in filter-mating experiments but also in a model oral biofilm.

Bacterial strains are listed in Table 1 and were grown at 37°C anaerobically (80% N2, 10% H2, and 10% CO2) except Neisseria subflava and Acinetobacter lwoffii, which were grown aerobically. All strains were grown on brain heart infusion agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood (E and O Laboratories, Bonnybridge, United Kingdom) and appropriate antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom) at concentrations of 10 μg ml−1 (tetracycline) and 25 μg ml−1 (rifampin). Tetr organisms from human saliva were isolated by spreading four aliquots of pooled saliva onto selective media and incubating the plates aerobically or anaerobically for 48 h.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used throughout this study

| Group (bacterial strain) | Relevant propertiesa |

|---|---|

| Saliva inoculum expt | |

| S. gordonii | |

| SG0 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated before inoculation of the CDFF) from saliva inoculum; contains a Tn916 element |

| SG240 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 240 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SG336 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 336 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SG408 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 408 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| S. mitis SM0 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated before inoculation of the CDFF) from saliva inoculum; contains a Tn916 element |

| S. oralis SO0 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated before inoculation of the CDFF) from saliva inoculum; contains a Tn916 element |

| S. parasanguinis SP72 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 72 h) contains a Tn916 element |

| S. sanguinis | |

| SS218 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 218 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SS221 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 221 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SS240 | Tetr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 240 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SS408 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 408 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| S. salivarius | |

| SSa10 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 10 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| SSa172 | Tetr Ermr isolate (isolated from the CDFF experiment after 172 h); contains a Tn916 element |

| 11-membered consortium | |

| S. oralis | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| S. mitis | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| S. parasanguinis | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| S. parasanguinis SP150 | Tetr transconjugant |

| S. gordonii | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Veillonella parvula | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Veillonella atypica | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Neisseria subflava | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| Acinetobacter lwoffii | Tets isolate from saliva inoculum |

| S. salivarius SSa10 | Tetr Ermr isolate was used as a donor in filter-mating and 11-member consortium experiments |

| Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 | Tets Rifr recipient for filter-mating experiments |

Rifr, rifampin resistant; Ermr, erythromycin resistant.

Filter-mating experiments were carried out as described previously (17). Transconjugants were selected on media containing tetracycline and rifampin. Multispecies microcosms were produced in a constant-depth film fermentor (CDFF), with nutrients supplied from artificial saliva, as described previously (12, 13, 20). Saliva samples from 10 healthy individuals were pooled, aliquoted, and frozen at −70°C. The CDFF was inoculated as described previously (12). At 216 h postinoculation the CDFF was pulsed with tetracycline in artificial saliva at concentrations of 2 μg ml−1 for 1 h and 12 μg ml−1 for 2 h followed by 2 μg ml−1 for 1 h. These concentrations mimic the levels found in gingival crevicular fluid after an oral dose of tetracycline (5). Selection of Tetr organisms was carried out as previously described (13). Growth of the biofilm consortia was carried out essentially as described above; the inoculum, consisting of 11 species of bacteria (Table 1) which had been grown overnight in 5 ml of brain heart infusion broth, was added to 445 ml of artificial saliva, which was pumped into the CDFF. The fermentor in this experiment was pulsed with tetracycline at 150 h.

Streptococci were identified using API 32 Strep kits (Biomerieux, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (9) and analyzed using the Ribosomal Database Project II (10). Due to the high degree of homology of the 16S rRNA gene sequences, further differentiation of the streptococcal species was achieved by carbohydrate fermentation, enzyme substrate utilization tests (18), and comparison of 16S rRNA-23S rRNA intergenic nucleotide sequences (19).

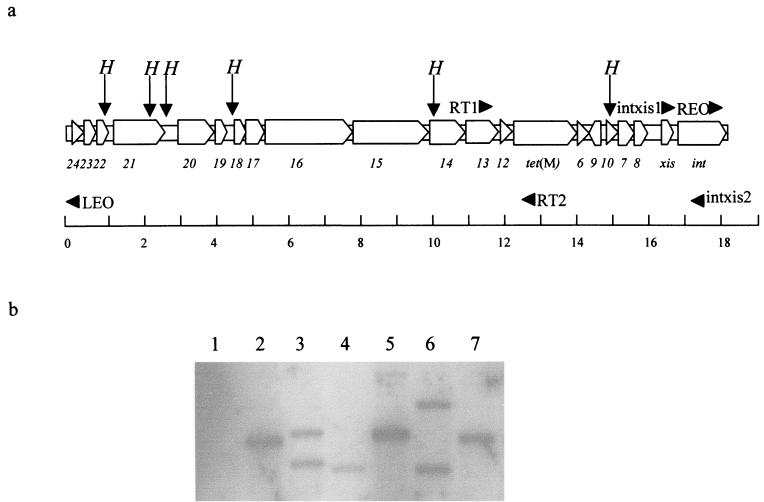

PCRs and sequencing reactions were performed as described previously (17). The positions and sequences of the primers (Sigma-Genosys Ltd., Pampisford, United Kingdom) used are shown in Fig. 1a and Table 2. Southern blots were carried out using ECL kits (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Enzymes were obtained from Promega (Southampton, United Kingdom).

FIG. 1.

(a) Tn916 showing the positions and names of the primers used in this study. The open reading frames of Tn916 are represented by unfilled arrows showing the probable direction of transcription and are named as described in the work of Flannagan et al. (4). The arrows labeled “H” show the positions of the HincII sites. Primers are shown as filled triangles (the point of a triangle shows the direction of priming) labeled with the names of the primers. The bottom line is the scale in kilobases. (b) HincII-digested genomic DNA from Tetr species isolated from the CDFF experiment and probed with a labeled PCR product derived from the xis and int genes present on Tn916. Lanes: 1, S. salivarius SSa10 (SSa172 showed a hybridization pattern identical to that of SSa10); 2, S. mitis SM0; 3, S. oralis SO0; 4, S. gordonii SG0; 5, S. parasanguinis SP72; 6, S. gordonii SG240 (SG336 and SG408 showed hybridization patterns identical to that of SG240); 7, S. sanguinis SS218 (SS221, SS240, and SS408 showed hybridization patterns identical to that of SS218).

TABLE 2.

Primers used throughout this work

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Amplification product |

|---|---|---|

| 27F | AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG | 16S rRNA gene |

| 1492R | TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT | |

| 1492F | AAGTCGTAACAAGGTARCCGTA | 16S-23S rRNA intergenic region |

| 188R | TACTMAGATGTTTCARTTC | |

| intxis1b | CGCCAAAGGATCCTGTATATG | xis and int fragment of Tn916 |

| intxis2b | GCTGTAGGTTTTATCAGCTTTTGC | |

| RT1 | CTCTATCCTACAGCGACAGC | orf13-tet(M) fragment of Tn916 |

| RT2 | ATATACGAGTTTGTGCTTGT | |

| REO | CGAAAGCACAGAGAATAAGGCTT TACGAGC | Joint of the circular form of Tn916 |

| LEO | GGTTTTGACCTTGATAAGTGTGAT AAGTCC |

Redundancies are as follows: M = C or A, Y = C or T, and R = A or G.

Primer sequence is from reference 11.

Before we inoculated the CDFF with the pooled human saliva, it contained the following Tetr (MIC, ≥32 μg ml−1) organisms: Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus gordonii, and Streptococcus salivarius. At 72 h the Tetr organisms isolated were Streptococcus parasanguinis and Streptococcus salivarius. Streptococcus sangiunis was isolated at 218, 221, and 240 h, and S. salivarius and S. parasanguinis could no longer be isolated. At 240, 336, and 408 h Tetr S. gordonii could also be isolated. S. sanguinis was isolated at 408 h.

To determine if a Tn916-like element was present a Southern blot was performed on HincII-digested genomic DNA (Fig. 1b). This blot was probed with a labeled PCR product from the int and xis regions of Tn916 (Fig. 1a and Table 2). As we were looking for functional Tn916 elements, the integration region was the best probe to use, as nonfunctional fragments of Tn916-like elements are found in many different bacteria (14, 16). Digestion with HincII will release a fragment containing the int and xis genes and the transposon-genome junction (Fig. 1). With Tn916 the number of hybridizing bands reflects the number of copies of the transposon. The hybridization showed that all of the streptococci possessed at least one copy of a Tn916-like element. We also demonstrated by PCR (primers RT1 and RT2) that all the Tetr streptococci contained the region from orf13 to tet(M) (results not shown). PCRs to detect the circular form of Tn916 (primers REO and LEO) were positive, indicating that the Tn916-like elements were being excised (results not shown).

Filter-mating experiments were carried out between each original streptococcal isolate and E. faecalis JH2-2. Transconjugants arose at 6 × 10−7 per recipient from S. salivarius SSa10 and S. gordonii SG0. No spontaneously resistant colonies were isolated. PCR, using the primers in Fig. 1, and Southern blot hybridization against the int-xis fragment of Tn916 produced identically sized products and positive hybridization, respectively, in the donor and the transconjugants; no PCR products or hybridization to the recipient DNA was observed (results not shown), indicating that a Tn916-like element was responsible for the transfer.

We set up a known biofilm consortium containing 10 tetracycline-sensitive (Tets) organisms and one Tetr organism, S. salivarius SSa10 (Table 1). After 150 h a Tetr S. parasanguinis organism could be isolated at every sampling occasion. A Tn916 element indistinguishable (determined by PCR, sequencing, and Southern blotting) from that in the donor was found in S. parasanguinis. The putative transconjugant could not be distinguished from the S. parasanguinis organism present in the initial inoculum by PCR amplification and partial sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. This experiment was repeated, and only the Tetr donor was isolated. The fact that no transfer was detected in the second experiment may be due to differences within the biofilm. The multispecies environment of the biofilm is more variable than the two-species environment used in filter matings.

This is the first demonstration of transfer of a native cTn within a model oral biofilm, an important finding because the oral cavity is one of the most colonized environments within humans and oral bacteria have the opportunity to come into contact with bacteria that pass through the oral cavity; also, oral bacteria can be readily transferred from one human to another. This work demonstrates that oral streptococci are responsible for harboring and disseminating these promiscuous mobile elements to other oral microflora.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to David Spratt for helpful discussions on the differentiation of streptococcal species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bentocha F, Clermont D, de Cespedes G, Horaud T. Natural occurrence of structures in oral streptococci and enterococci with DNA homology to Tn916. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:59–63. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clewell D B, Flannagan S E, Jaworski D D. Unconstrained bacterial promiscuity: the Tn916-Tn1545 family of conjugative transposons. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald G F, Clewell D B. A conjugative transposon (Tn919) in Streptococcus sanguis. Infect Immun. 1985;47:415–420. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.415-420.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flannagan S E, Zitzow L A, Su Y A, Clewell D B. Nucleotide sequence of the 18 kb conjugative transposon Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1994;32:350–354. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon J M, Walker C B, Murphy J C, Goodson J M, Socransky S S. Concentration of tetracycline in human gingival fluid after single doses. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;8:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1981.tb02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartley D L, Jones K R, Tobian J A, LeBlanc D J, Macrina F L. Disseminated tetracycline resistance in oral streptococci: implication of a conjugative transposon. Infect Immun. 1984;45:13–17. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.13-17.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuramitsu H K, Trapa V. Genetic exchange between oral streptococci during mixed growth. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2497–2500. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-10-2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacroix J M, Walker C B. Detection and incidence of the tetracycline resistance determinant tet(M) in the microflora associated with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1995;66:102–108. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 1996. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Lilburn T G, Parker C T, Jr, Saxman P R, Stredwick J M, Garrity G M, Li B, Olsen G J, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) continues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:173–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marra D, Scott J R. Regulation of excision of the conjugative transposon Tn916. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:609–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratten J, Smith A W, Wilson M. Response of single species biofilms and microcosm dental plaques to pulsing with chlorhexidine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:453–459. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts A P, Pratten J, Wilson M, Mullany P. Transfer of a conjugative transposon, Tn5397 in a model oral biofilm. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:63–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts A P, Johanesen P A, Lyras D, Mullany P, Rood J I. Comparison of Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile, Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis and the CW459tet(M) element from Clostridium perfringens shows that they have similar conjugation regions but different insertion and excision modules. Microbiology. 2001;147:1243–1251. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seymour R A, Heasman P A. Tetracyclines in the management of periodontal diseases. A review. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:22–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swartley J S, McAllister C F, Hajjeh R A, Heinrich D W, Stephens D S. Deletions of Tn916-like transposons are implicated in tetM-mediated resistance in pathogenic Neisseria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Roberts A P, Lyras D, Rood J I, Wilks M, Mullany P. Characterization of the ends and target sites of the novel conjugative transposon Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile: excision and circularization is mediated by the large resolvase, TndX. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3775–3783. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3775-3783.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whiley R A, Beighton D. Current classification of the oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:195–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiley R A, Duke B, Hardie J M, Hall L M. Heterogeneity among 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacers of species within the ‘Streptococcus milleri group’. Microbiology. 1995;141:1461–1467. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson M. Use of constant depth film fermentor in studies of biofilms of oral bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:264–279. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]