Abstract

Background As the COVID-19 pandemic persists and new vaccines are developed, concerns among the general public are growing that both infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and vaccinations against the coronavirus (mRNA vaccines) could lead to infertility or higher miscarriage rates. These fears are voiced particularly often by young adults of reproductive age. This review summarizes the current data on the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection and corona vaccinations on female and male fertility, based on both animal models and human data.

Method A systematic literature search (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science) was carried out using the search terms “COVID 19, SARS-CoV-2, fertility, semen, sperm, oocyte, male fertility, female fertility, infertility”. After the search, original articles published between October 2019 and October 2021 were selected and reviewed.

Results Despite the use of very high vaccine doses in animal models, no negative impacts on fertility, the course of pregnancy, or fetal development were detected. In humans, no SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in the oocytes/follicular fluid of infected women; similarly, no differences with regard to pregnancy rates or percentages of healthy children were found between persons who had recovered from the disease, vaccinated persons, and controls. Vaccination also had no impact on live-birth rates after assisted reproductive treatment. No viral RNA was detected in the semen of the majority of infected or still infectious men; however, a significant deterioration of semen parameters was found during semen analysis, especially after severe viral disease. None of the studies found that corona vaccines had any impact on male fertility.

Discussion Neither the animal models nor the human data presented in recent studies provide any indications that fertility decreases after being vaccinated against coronavirus. However, there is a growing body of evidence that severe SARS-CoV-2 infection has a negative impact on male fertility and there is clear evidence of an increased risk of complications among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The counseling offered to young adults should therefore take their fears and concerns seriously as well as providing a structured discussion of the current data.

Key words: COVID-19, corona vaccine, SARS-CoV-2, reproduction, sperm, oocyte, embryo, infertility

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the new beta-coronavirus, referred to by the WHO as 2019-nCov and by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Emerging in the final months of 2019, the disease has since triggered a global pandemic which has infected at least 326.3 million people and led to 5.53 million deaths (as per 17 January 2022) 1 , 2 .

Although the prevalence of disease has been approximately the same, a significant gender bias has been found with regard to both severity of disease and mortality 3 , 4 : men have a higher risk of requiring intubation and spend a longer time in hospital compared to women. In addition, the mortality rate in men is higher, even after comparing age groups and ethnicities and taking co-morbidities into account 5 . A possible protective effect of female but also male sexual hormones is currently being discussed in this context 6 , 7 . After acute infection, 2.3% of persons who fell ill report persistent side effects (> 12 weeks) in the form of so-called long/post-COVID syndrome 8 , 9 . The syndrome is characterized by symptoms such as fatigue, headache, dyspnea and anosmia and occurs more commonly in older patients (> 52 years), patients with a higher body mass index (BMI > 26), patients who have previously had severe COVID-19, and women 10 , 11 . In patients below the age of 52 years, SARS-CoV-2 infection is generally associated with lower morbidity and mortality rates than in older infected persons, with a lower percentage (25%) of “critically” ill patients according to the COVID-19 score 12 , 13 , 14 . However, the delta variant of the virus has also led to an increasing rate of hospitalizations among young adults aged between 18 and 34 years. 21% of patients in this patient population require intensive care. The mortality rate of 2.7% is twice as high as that occurring following myocardial infarction in the same age group 15 .

Initial studies have shown an impact on male fertility in severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19, particularly on sperm motility and morphology 16 , 17 , 18 . There is not much current data on the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on female fertility, particularly on oocyte quality, as assisted reproductive treatment is not carried out in cases with acute infection and oocytes are therefore not examined 19 .

Caring for pregnant women during a pandemic is a challenge. At the beginning of the pandemic, it was assumed that placental transmission of maternal infection did not occur 20 ; however, recent data have shown changes in the placenta of SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers, such as vascular malperfusion with increased syncytial knots and focal perivillous fibrin depositions 21 , 22 . Moreover, a reduction in mtDNA values was found in the placentas of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This is significantly associated with oxidative DNA damage and indicates that the placenta is under severe oxidative stress 23 . Pregnant women with COVID-19 also have a more severe course of disease compared to non-pregnant women 24 . The time spent in hospital is longer and the likelihood that they will require ventilatory support and may need to be moved to intensive care is higher for pregnant women 25 . Moreover, rates of cesarean section and preterm birth rates for fetal distress are higher for pregnant women who are SARS-CoV-2-positive 26 , 27 , 28 .

To date, the EU has approved two mRNA vaccines and two viral vector vaccines to contain the pandemic. Both mRNA vaccines have been shown to be 95% effective for the prevention of severe COVID-19 disease in the age group between 12 – 17 years, 85% effective in persons aged 18 – 39 years, and 86% effective in persons older than 40 years 29 , 30 . Vaccination with the vector vaccine by AstraZeneca resulted in 61% protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection with severe symptoms of disease for persons aged 18 – 39 years, 72% protection for persons aged 40 – 59 years and 80% protection for people above the age of 60 years 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 .

The rapid development and approval of these vaccines combined with the simultaneous spread of misinformation across social media has not just raised fears among persons strongly opposed to vaccinations. Such fears can include worries about possible long-term consequences, including the long-term impact on the fertility of vaccinated persons 33 , 34 . Such fears and concerns can only be countered by a detailed, structured presentation of the data available in recent studies. This article therefore presents the current data on possible impacts of corona vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection on fertility using both animal models and human data.

Available Vaccines and Currently Established Animal Models

Two different types of vaccine are currently approved for use against the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the European Union (EU): two mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 from BioNTech/Pfizer and mRNA-1273 from Moderna) and two viral vector vaccines (AZD1222 from AstraZeneca, JNJ-78436735 from Janssen).

Viral vector vaccines function by incorporating the DNA for the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in a modified adenovirus; the DNA is introduced into the cellʼs nucleus and transcribed in the RNA, which results in the production of spike proteins. The spike proteins are then transported to the cell surface, where they induce a targeted cellular and humoral immune response. This leads to the production of specific antibodies against the spike protein on the surface of the virus. In the event of an infection, the spike protein epitopes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are recognized and neutralized with the help of the available antibodies 32 , 35 . With mRNA vaccines, the viral RNA needed to create spike proteins is directly absorbed by the cells around the vaccination site through endocytosis. With this type of vaccine, the mRNA is enveloped by lipid nanoparticles to protect and allow it to enter cells of the body without being immediately broken down again. The viral RNA is then decoded, translated into spike proteins by the bodyʼs own ribosomes, and the antigen is transported to the surface of the cell. As with the immune response elicited by vector vaccines, the use of mRNA vaccines also results in the production of specific antibodies 29 , 31 , 36 . What is important is that just a few days later, no adenoviruses can be detected in persons who received vector vaccines and no spike protein-coding mRNA can be detected in the human organism of persons who received mRNA vaccines 29 , 31 , 32 .

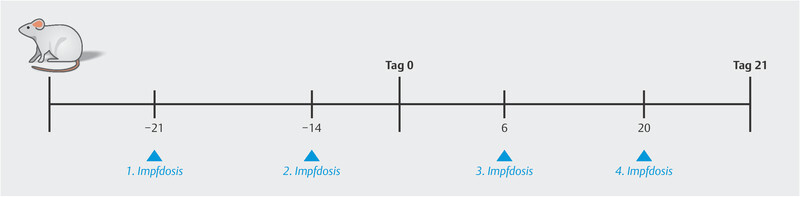

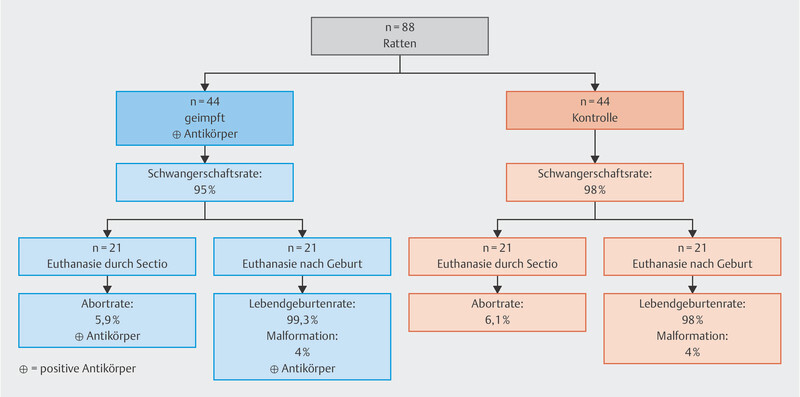

Several animal models have been used to investigate the possible side effects of a corona vaccine on fertility, pregnancy and offspring. Bowman et al. analyzed the impact of vaccinations using the mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2) on female fertility and the course of pregnancy in rats ( Fig. 1 ). The study was carried out in a total of 88 female rats of reproductive age. The control group was injected with a saline solution, while the rats in the study group received a total of 4 doses of the mRNA vaccine (30 μg/vaccination). Dosages were selected to be similar to the doses given to humans (70 kg) and were therefore 300 × higher than human doses on a μg/kg basis (220 g) 37 .

Fig. 1.

Study design and timing of administration of the vaccine (BNT162b2). Day 0 = start of gestation period, Day 21 = C-section or delivery 37 .

Injections were administered to all of the animals before the start of gestation (Day 0) and during pregnancy. Half of the rats in both the control group and the study group (n = 21/group) were euthanized and classified as the cesarean section group. The remaining animals and their offspring were examined after delivery. No differences with regard to fertility, duration of pregnancy, miscarriage or live-birth rates were found between the study group and the control group, although the rats received a 300-fold dose of the vaccine. In addition, all animals and their offspring in the study group had positive antibody titers against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein ( Fig. 2 ) 37 .

Fig. 2.

Course of the study 37 .

Another study investigated the safety of the vector vaccine Vaxzevria manufactured by AstraZeneca (AZD1222), with regard to the fertility and development of offspring in a mouse model. Both study phases focused on the developmental and postpartum period. In the 1st phase, the first dose of vaccine (0.035 ml) was injected on Day 14 (= Day 0 of gestation) and the second on Day 6 of gestation. Day 0 corresponded to the date of fertilization and C-section was carried out on Day 17. As the dose in humans (70 kg) is 0.5 ml, the dose administered to each mouse (30 g) was 163 × higher. In a 2nd phase, vaccines were administered after fertilization (Day 0), with the first vaccine dose administered on Day 6 after gestation and the second dose on Day 15. Animals and their offspring were investigated post partum. The viral vector vaccine used had no impact on fertility, the course of pregnancy, or offspring.

After having received the vaccination, animals showed no loss of appetite and experienced no weight loss. The pregnancy rate (PR) in the study group was 92% and the rate of spontaneous abortion was 6.8%, which did not differ from the control group (PR 94%, abortion rate 7.5%). The malformation rate for the offspring of the study group was 0.6% compared to 1.8% in the control group 38 .

Female Fertility and SARS-CoV-2 Infection or Vaccination

To determine the impact of an infection on individual cell types, the first questions that need to be answered are the fundamental questions whether and how cells can be infected. To understand the impact on female fertility, there must be an impact on the ovaries, particularly on the oocytes. Stanley et al. 33 showed in a small study population (n = 18) that human cumulus cells show no or only minimal RNA expression of transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) which is a point of entry for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The same study detected RNA expression of TMPRSS2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the ovarian cells of primates. SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2, which is encoded on the X chromosome, as a receptor to enter human cells. The more advanced the developmental stage of the oocytes, the more it was possible to detect expression of both proteins. The highest expression was found in the antral follicles 39 . This means that in a primate model, oocytes are most vulnerable just before ovulation or just prior to follicular atresia during the physiological cycle. The data on human oocytes is limited; there are only 3 case reports of women proven to have SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of follicular aspiration during assisted reproductive treatment 19 , 40 . No viral RNA was found in either the follicular fluid of a symptomatic patient 19 or the oocytes of two asymptomatic patients 40 . No infection was detected in the oocytes of these women even though, according to the animal model, they were in the most vulnerable phase of folliculogenesis.

A long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on ovarian function or ovarian reserve has not been detected. Wang et al. 35 reported on 4043 ART cycles in Wuhan, 70 of which were in patients found to be positive for IgG/IgM SARS-CoV-2 antibodies compared to women without detected antibodies. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, antral follicle count (AFC), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, number of retrieved oocytes, and pregnancy rate 41 .

A recently published study also found no differences in ovarian reserve (measured using AMH over the course of one year) between patients who had recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection and patients who had not been infected 43 .

Another study analyzed AMH values as well as serum concentrations of testosterone, estradiol, progesterone, LH and FSH in patients who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. The study found no differences compared to age-matched controls 44 . However, changes in menstrual cycles did occur after SARS-CoV-2 infection, irrespective of the severity of infection 44 .

Two further studies investigated the question whether vaccination has a significant impact on ovarian reserve 42 , 45 . One study compared the outcomes of assisted reproductive treatment (ART) cycles in couples who were not yet vaccinated and in couples who received two vaccinations with an mRNA vaccine; no differences were found in the number of (mature) oocytes or blastocysts 42 . The second study also found no differences in follicular function during ART cycles between women who had recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection, women vaccinated with an mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2), and healthy patients 45 ( Table 1 ). The effects of a corona vaccination on menstrual cycles are still largely unknown. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development has recently provided $1.67 million in research funding to investigate possible associations.

Table 1 Impact of corona vaccinations on assisted reproductive treatment (ART) cycles.

| Bentov et al. 43 | Orvieto et al. 40 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Recovered | Control | p-value | Before | After | p-value | |

| Data are given as mean ± SD, ns = not significant | |||||||

| Number of patients | 9 | 9 | 14 | 36 | 36 | ||

| Age in years | 35.3 ± 3.97 | 34.1 ± 4.7 | 32.5 ± 5.3 | ns | 37.3 ± 17.5 | ||

| Antral follicle count | 13.3 ± 4.7 | 13.6 ± 4.1 | 15.6 ± 6.7 | 0.008 | – | – | – |

| Estradiol peak (Pmol/L) | 8874 ± 2555 | 10 810 ± 5867 | 8379 ± 4167 | ns | 6041 ± 4052 | 7708 ± 7640 | ns |

| Progesterone peak (nmol/L) | 3.29 ± 2.09 | 3.31 ± 1.14 | 1.64 ± 0.67 | ns | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | ns |

| Number of oocytes | 12.4 ± 8.7 | 10.89 ± 4.8 | 11.2 ± 6.7 | ns | 9.7 ± 6.7 | 10.1 ± 8 | ns |

| Number of mature oocytes | 7.25 ± 2.77 | 8.37 ± 4.1 | 7.75 ± 4.7 | ns | 7.94 ± 5.7 | 8.0 ± 6.5 | ns |

| Number of good-quality embryos | 0.43 ± 0.5 | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.34 | ns | 2.8 ± 2.7 | 2.8 ± 3.3 | ns |

One of the first vaccine myths centered on the fear that corona vaccines could lead to infertility. The reason given for this assumption was a supposed similarity between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and syncytin-1, a protein that plays a role in implantation and placental development. This led to concerns being voiced on social media about the possible effect of vaccines on fertility. However, it has been shown that there is no evidence or functional basis for this hypothetical cross-immunity as the two proteins are completely different with regard to their composition and immunogenicity. It has also been shown that neither antibodies which develop after receiving a SARS-CoV2 vaccine nor antibodies which are present after infection with SARS-CoV2 bind to syncytin-1 and they can therefore not cause infertility 46 . This was also highlighted in post-marketing observational studies after the mRNA vaccines had been approved, which found no differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated women with regard to the incidence of pregnancies with no complications 47 . A recent study of 993 pregnant women who were vaccinated with a mRNA vaccine in their 2nd or 3rd trimester of pregnancy found no differences with regard to the course of pregnancy and birth compared to unvaccinated women 48 .

The data presented here show that concerns that corona vaccines may make women infertile are unfounded.

Male Fertility and SARS-CoV-2 Infection or Corona Vaccination

To investigate possible effects on the male reproductive system, it is necessary to study the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, spermatogenesis/spermiogenesis, and testosterone production 49 . It is also important to differentiate between SARS-CoV-2 infections which take a severe course and those that do not. Severe SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection is accompanied by high fever and a significant decrease in overall health; the unspecific effects on male fertility which also occur in the context of other infectious diseases must be differentiated from the specific effects caused by SARS-CoV-2 50 .

As some of the men who fell ill with COVID-19 complained of testicular pain, it became clear early on that gonadal involvement could not be excluded in cases with serious infection 55 .

Histological examinations of testicular tissue obtained from men who had died either from or with COVID-19 showed damage to the seminiferous tubules and to Sertoli and Leydig cells 51 .

As ACE2 is expressed in the spermatogonia and Sertoli and Leydig cells in the testes, there is a suspicion that the virus might be targeting these cells and that infection could affect male fertility 52 , 53 . SARS-CoV-2 uses spike proteins to bind to ACE2. TMPRSS2 then breaks down the S protein into S1 and S2 subunits. The S2 subunit promotes fusion of the membranes of the virus with those of the host cell, allowing viral RNA to enter the infected cell 54 . The data on the expression of TMPRSS2 in male genitalia is still contradictory 54 . As ACE2 receptors and TMPRSS-2 are influenced by androgens, it is important to consider possible specific effects of an infection with SARS-CoV-2 on the male organism and genital tract 55 – 61 .

A total of 21 original studies were found which investigated to what extent it is possible to detect SARS-CoV-2 in semen and whether SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces male fertility 16 , 17 , 18 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 ( Table 2 ). Two papers investigated semen parameters before and after COVID-19 vaccination 74 , 75 .

Table 2 Summary of recent studies on SARS-CoV-2 infection and male fertility.

| Author (year) | COVID-19 status 1 | Characteristics | Study population (n, patients/controls) | Age (median) | SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in semen | Sperm: concentration (million/ml) | Sperm: motility, WHO A+B (%) | Sperm: morphology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

Severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection was classified according to the COVID-19 Guideline (Xu et al. 2020

13

). Mild: clinical symptoms

are mild and there are no indications of pneumonia on chest imaging. Moderate: patients present with fever and respiratory symptoms; pneumonia is detected on chest imaging. Severe:

adult patients have at least one of the following symptoms: respiratory frequency of 30/min, oxygen saturation ≤ 93% at rest, partial arterial pressure of oxygen ≤ 300 mmHg. Children

present with at least one of the following symptoms: dyspnea (except when crying), oxygen saturation ≤ 92% at rest, ventilatory assistance, cyanosis, lethargy, unconscious, food is

rejected, dehydration. Critical: at least one of the following symptoms is present: respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory assistance, shock, organ failure requiring

monitoring and ICU.

2 Sperm parameters above WHO reference values are referred to as “normal range”: sperm concentration ≥ 15 × 10 6 /ml; sperm motility: percentage of progressive motile sperm ≥ 32%; percentage of morphologically unremarkable sperm ≥ 4%. Values below WHO references values are referred to as “pathological” (Nieschlag et al. 2021 82 , 84 ). 3 In studies which compared sperm parameters before and after SARS-CoV-2 infection, non-significant differences (p > 0.05) are reported as “no significant change” and significant deterioration (p < 0.05) as “significant deterioration”. | ||||||||

| Holtmann N (2020) | no infection | – | 14 | 33 | negative | normal range 2 | normal range | not investigated |

| could not be classified based on Guidelines | recovered; two patients with acute infection | 14 | 43 | negative | normal range | normal range | not investigated | |

| severe | 4 | 41 | negative | normal range | pathological 2 | not investigated | ||

| Paoli D (2020) | not tested; no symptoms | patients with different malignant neoplasms | 10 | 31 | negative | normal ranges | normal range | normal range |

| Gacci M (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | recovered; not hospitalized | 12 | 44 | negative | normal range | normal range | pathological |

| recovered; hospitalized (normal ward) | 26 | 52 | negative | normal range | pathological | pathological | ||

| critical | recovered; hospitalized (intensive care unit) | 5 | 59 | one person was positive | pathological | pathological | pathological | |

| Temiz MZ (2020) | moderate | smoker | 10 | 38 | negative | normal range | normal range | normal range |

| 10 | 37 | |||||||

| Maleki BH (2021) | mild | corticosteroid therapy, semen quality analysis during and after infection | 1 | 35 | not investigated | pathological | pathological | pathological |

| moderate | 23 | |||||||

| severe | 27 | |||||||

| critical | 33 | |||||||

| Pazir Y (2021) | mild | 50% nicotine abuse, semen quality analysis before and after infection | 24 | 35 | not investigated | no significant change | no significant change | not investigated |

| Honggang L (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | – | 23 | 41 | negative | pathological | not investigated | not investigated |

| Guo TH (2021) | mild to severe | – | 41 | 26 | not investigated | normal range | normal range | normal range |

| Erbay G (2021) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | before and after COVID-19 infection | 69 | 31 | not investigated | normal range | normal range | normal range |

| Koç E (2021) | not reported | before and after COVID-19 infection | 21 | 32 | not investigated | no significant change | significant deterioration | significant deterioration |

| Best JC (2021) | not reported | – | 30 | 40 | negative | pathological | not investigated | not investigated |

| Pan F (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | 50% of men had a BMI > 25; 3 men had hypertension | 34 | 37 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Song C (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | one man (age: 67) died of SARS-CoV-2 | 13 | 33 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Li D (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | 23 men recovered; 15 men with acute infection | 38 | not specified | 6 people positive | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Paoli D (2020) | moderate | dyslipidemia (treatment with simvastatin 20 mg/d for 1 year); androgenetic alopecia (topical treatment with finasteride 1 mg/d); cruciate ligament reconstruction | 1 | 31 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Huang C (2020) | not reported | qualified sperm donors | 100 | not specified | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Ruan Y (2021) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | tested positive with RT-PCR and recovered completely | 55 | 31 | negative | normal range | normal range | not investigated |

| Burke CA (2021) | tested positive | no one hospitalized | 19 | 32 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Kayaaslan B (2020) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | all hospitalized | 16 | 34 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

| Ma L (2021) | could not be classified based on Guidelines | 11 already recovered | 12 | 32 | negative | normal range | normal range | normal range |

| Pavone C (2020) | tested positive | no one hospitalized | 9 | 42 | negative | not investigated | not investigated | not investigated |

SARS-CoV-2 Infection

At the start of the pandemic, one of the important issues was whether SARS-CoV-2 could be sexually transmitted. Most of the 21 studies which examined this issue reported that no SARS-CoV-2 RNA could be detected in semen 16 , 17 , 18 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 ( Table 2 ). Only two studies reported positive findings 16 , 72 . In the study by Baldi et al. 13 , RT-PCR analysis for SARS-CoV-2 in semen was positive in one patient with critical symptoms. However, SARS-CoV-2 was also detected in the urine of this patient and it is therefore assumed that the semen sample was contaminated. Similarly, it was not possible to exclude contamination in the study by Li et al. 57 , which reported on six patients with a positive RT-PCR, as the time of last micturition was not recorded. The study also had a number of methodological errors. It is therefore currently assumed that the semen of men who are positive for SARS-CoV-2 is not infectious.

In the studies discussed here, male fertility during and after SARS-CoV-2 infection was evaluated using individual sperm parameters in accordance with the 5th edition of the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, published in 2010 82 . Because of the possible RNA-genome interaction, some of the studies additionally carried out reverse transcriptase-polymerase-chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect SARS-CoV-2 in semen samples. A few of the studies additionally analyzed semen samples to identify cytokines and other immune parameters 18 , 65 .

Semen analysis of patients was carried out in 13 of the original studies discussed here 16 , 17 , 18 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 77 , 80 . Four of the 13 found abnormalities with regard to sperm concentrations (million/ml) 16 , 18 , 65 , 69 . In 11 of the 13, semen analysis included an examination of sperm motility, and 4 of the 11 detected a deterioration of motility 16 , 17 , 18 , 68 . Eight of the 13 studies also analyzed sperm morphology, and three of the studies reported higher rates of morphologically abnormal sperm 16 , 18 , 68 . Two of the 13 original studies compared semen quality parameters of patients before and after having had COVID-19. One of these two studies reported a significant deterioration in motility and morphology after recovering from disease 64 , 68 .

In summary, it is important to be aware that the total number of semen analyses from men infected with SARS-CoV-2 examined in original studies is < 500. One third of the studies found changes, some of them significant, in the three relevant semen parameters. Severe COVID-19 disease in particular was found to lead to a reduction in sperm concentrations and motility and an increase in morphological abnormalities. It is also important to be aware of additional effects on spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis, particularly in men who have severe COVID-19 and experience a significant overall deterioration requiring hospitalization and treatment in an intensive care unit including life-sustaining measures.

Corona Vaccination

The data on the effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on male fertility includes two papers which studied the impact of the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2. Safrai et al. investigated the sperm quality of 43 men (37.1 ± 6 years) before and after being vaccinated 74 . Their semen was examined before and 33.6 ± 20.2 days after the first vaccination. Sperm concentrations before and after the vaccination were unaffected (43.6 ± 58 × 10 6 /ml vs. 47 ± 54.8 × 10 6 /ml; p = 0.7); there were also no significant changes in sperm motility (percentage of motile sperm × 10 6 : 48.5 ± 83.4 vs. 61.7 ± 92.9; p = 0.4). A second study included a total of 45 men (aged 28 ± 3 years) who were investigated before and after receiving two doses of BNT162b2 75 . Sperm samples were investigated before and on average 75 days (70 – 86 days) after receiving the second vaccination. Sperm concentrations before and after the vaccination were unaffected (respective median and interquartile interval: 26 [19.5 – 34] × 10 6 /ml vs. 30 [21.5 – 40.5] × 10 6 /ml; p = 0.2). Sperm motility was also unaffected (respective median and interquartile interval for the percentage of motile sperm × 10 6 : 58 [52.5 – 65] vs. 65 [58 – 70]; p = 0.001). Both studies confirm that sperm quality does not deteriorate after a corona vaccination.

Another study by Carto et al. investigated the association between approved COVID-19 vaccines and the occurrence of orchitis and/or epididymitis within 1 – 9 months after receiving the vaccine. A total of 663 774 men who had received at least one vaccination were compared with 9 985 154 men who were not vaccinated. Orchitis and/or epididymitis occurred significantly less often in men who had been vaccinated (OR = 0.568; 95% CI: 0.497 – 0.649; p < 0.0001) 83 .

Importance for Male Patients

In some men, infection with SARS-CoV-2 will negatively affect the quality of their sperm, depending on the severity of infection. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine does not result in any deterioration of sperm. In view of the potential impact of disease on male fertility, vaccinations should be recommended to men, especially as the possibility cannot be excluded that other testicular functions, for example the function of Leydig cells, could also be negatively affected by infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

In the animal models, vaccination with BNT162b2 or AZD1222 was found to have no effect on fertility and had no negative impact on existing pregnancies compared to placebo 38 . Moreover, antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were detected in the offspring in animal models 37 . This is particularly remarkable given the fact that animals were given far higher doses of the vaccines compared to humans.

Up to now, SARS-CoV-2 RNA has not been detected in the oocytes or follicular fluid of women proven to have had SARS-CoV-2 infection 19 , 40 . Similarly, no changes in ovarian reserve, specifically, no changes in AMH concentrations, were found in women who had recovered from COVID-19 infection 32 , 43 . Likewise, vaccination with mRNA vaccines did not change the ovarian response and was associated with good success rates in cases who were undergoing ART 42 , 45 .

Numerous studies found no traces of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the sperm samples of infected men 16 , 17 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 73 , 76 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 . As regards the two studies which detected viral RNA in sperm samples, the international debate has highlighted specific methodological errors made in the two studies 16 , 72 . In contrast to these studies, comparisons of semen parameters taken before and after men were vaccinated found that corona vaccines had no negative impact on male fertility 74 , 75 , 83 . However, male fertility was found to be at least temporarily impaired after SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in severe cases of disease, with more than one third of studies showing a deterioration of all 3 relevant semen parameters.

Based on the available data, the perennial question whether COVID vaccines lead to infertility can be answered with a resounding “No!”. But the erroneous belief that vaccines cause infertility has unfortunately taken hold among many young people wishing to have children and those who may wish to have children in future. Providing factual information is essential when attempting to change such beliefs, but it is also important to take the anxieties and concerns of target groups seriously and discuss them in detail. Social media channels which are able to reach a big audience, particularly channels used extensively by people under the age of 30, could be useful in this context.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autorinnen/Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.WHO WHO Coronavirus (Covid-19) DashboardAccessed January 17, 2022 at:https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Andersen K G, Rambaut A, Lipkin W I. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26:450–452. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin J-M, Bai P, He W. Gender Differences in Patients With COVID-19: Focus on Severity and Mortality. Front Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chauvin M, Larsen M, Quirant B. Elevated Neopterin Levels Predict Fatal Outcome in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.709893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen N T, Chinn J, De Ferrante M. Male gender is a predictor of higher mortality in hospitalized adults with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0254066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Klein S L, Levin E R. Estradiol, Progesterone, Immunomodulation, and COVID-19 Outcomes. Endocrinology. 2020 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanser L, Burkert F R, Thommes L. Testosterone Deficiency Is a Risk Factor for Severe COVID-19. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:694083. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.694083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund L C, Hallas J, Nielsen H. Post-acute effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals not requiring hospital admission: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:1373–1382. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonnweber T, Sahanic S, Pizzini A. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19: an observational prospective multicentre trial. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2.003481E6. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03481-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudre C H, Murray B, Varsavsky T. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo A E. Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2128568. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho F K, Petermann-Rocha F, Gray S R. Is older age associated with COVID-19 mortality in the absence of other risk factors? General population cohort study of 470,034 participants. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Chen Y, Tang X. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. Glob Health Med. 2020;2:66–72. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim L, Garg S, OʼHalloran A. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality Among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the US Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e206–e214. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham J W, Vaduganathan M, Claggett B L. Clinical Outcomes in Young US Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gacci M, Coppi M, Baldi E. Semen impairment and occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in semen after recovery from COVID-19. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1520–1529. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtmann N, Edimiris P, Andree M. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in human semen–a cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajizadeh Maleki B, Tartibian B. COVID-19 and male reproductive function: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Reproduction. 2021;161:319–331. doi: 10.1530/rep-20-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demirel C, Tulek F, Celik H G. Failure to Detect Viral RNA in Follicular Fluid Aspirates from a SARS-CoV-2-Positive Woman. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:2144–2146. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00502-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klaritsch P, Ciresa-König A, Pristauz-Telsnigg G. COVID-19 During Pregnancy and Puerperium – A Review by the Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020;80:813–819. doi: 10.1055/a-1207-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao L, Ren J, Xu L. Placental pathology of the third trimester pregnant women from COVID-19. Diagn Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13000-021-01067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong Y P, Khong T Y, Tan G C. The Effects of COVID-19 on Placenta and Pregnancy: What Do We Know So Far? Diagnostics. 2021;11:94. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandò C, Savasi V M, Anelli G M. Mitochondrial and Oxidative Unbalance in Placentas from Mothers with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Antioxidants. 2021 doi: 10.3390/antiox10101517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stumpfe F M, Titzmann A, Schneider M O. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pregnancy – a Review of the Current Literature and Possible Impact on Maternal and Neonatal Outcome. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020;80:380–390. doi: 10.1055/a-1134-5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delahoy M J, Whitaker M, OʼHalloran A. Characteristics and Maternal and Birth Outcomes of Hospitalized Pregnant Women with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19 – COVID-NET, 13 States, March 1–August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1347–1354. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:823–829. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medeiros K S, Sarmento A CA, Martins E S. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e039933. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magee L A, Von Dadelszen P, Kalafat E. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy–number needed to vaccinate to avoid harm. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00691-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polack F P, Thomas S J, Kitchin N. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chalupka A, Handra N, Richter L.Estimates of COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infections following a nationwide vaccination campaign AGES; 2021. Accessed November 19, 2021 at:https://www.ages.at/fileadmin/Corona/Immunschutz/Impfeffektivität_der_in_Österreich_eingesetzten_COVID19-Impfstoffe_Ergebnisse_einer_populatonsbasierten_Kohortenstudie__KW_05-35.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baden L R, El Sahly H M, Essink B. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voysey M, Clemens S AC, Madhi S A. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson L C, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif. 2021;172:110590. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz P, Reddy P, Ramasahayam R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy linked to increased internet search queries for side effects on fertility potential in the initial rollout phase following Emergency Use Authorization. Andrologia. 2021 doi: 10.1111/and.14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatsis N, Ertl H CJ. Adenoviruses as vaccine vectors. Mol Ther. 2004;10:616–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardi N, Hogan M J, Porter F W. mRNA vaccines – a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:261–279. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowman C J, Bouressam M, Campion S N. Lack of effects on female fertility and prenatal and postnatal offspring development in rats with BNT162b2, a mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine. Reprod Toxicol. 2021;103:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stebbings R, Maguire S, Armour G. Developmental and reproductive safety of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2021;104:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanley K E, Thomas E, Leaver M. Coronavirus disease-19 and fertility: viral host entry protein expression in male and female reproductive tissues. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barragan M, Guillén J J, Martin-Palomino N. Undetectable viral RNA in oocytes from SARS-CoV-2 positive women. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:390–394. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Yang Q, Ren X. Investigating the impact of asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection on female fertility and in vitro fertilization outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101013. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orvieto R, Noach-Hirsh M, Segev-Zahav A. Does mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine influence patientsʼ performance during IVF-ET cycle? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2021;19:69. doi: 10.1186/s12958-021-00757-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolanska K, Hours A, Jonquière L. Mild COVID-19 infection does not alter the ovarian reserve in women treated with ART. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li K, Chen G, Hou H. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bentov Y, Beharier O, Moav-Zafrir A. Ovarian follicular function is not altered by SARS-CoV-2 infection or BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:2506–2513. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girardi G, Bremer A A. Scientific Evidence Supporting Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine Efficacy and Safety in People Planning to Conceive or Who Are Pregnant or Lactating. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:3–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen F, Zhu S, Dai Z. Effects of COVID-19 and mRNA vaccines on human fertility. Hum Reprod. 2021 doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wainstock T, Yoles I, Sergienko R. Prenatal maternal COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy outcomes. Vaccine. 2021;39:6037–6040. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Köhn F-M, Schuppe H-C. Auswirkungen von COVID-19 auf die männliche Fertilität. J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 2021;18:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sergerie M, Mieusset R, Croute F. High risk of temporary alteration of semen parameters after recent acute febrile illness. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:9700–9.7E9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang M, Chen S, Huang B. Pathological Findings in the Testes of COVID-19 Patients: Clinical Implications. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6:1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Xu X. scRNA-seq Profiling of Human Testes Reveals the Presence of the ACE2 Receptor, A Target for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Spermatogonia, Leydig and Sertoli Cells. Cells. 2020;9:920. doi: 10.3390/cells9040920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verma S, Saksena S, Sadri-Ardekani H. ACE2 receptor expression in testes: implications in coronavirus disease 2019 pathogenesis†. Biol Reprod. 2020;103:449–451. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioaa080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borges E, Setti A S, Iaconelli A. Current status of the COVID-19 and male reproduction: A review of the literature. Andrology. 2021;9:1066–1075. doi: 10.1111/andr.13037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pascolo L, Zito G, Zupin L. Renin Angiotensin System, COVID-19 and Male Fertility: Any Risk for Conceiving? Microorganisms. 2020;8:1492. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8101492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vishvkarma R, Rajender S. Could SARS-CoV-2 affect male fertility? Andrologia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/and.13712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Younis J S, Abassi Z, Skorecki K. Is there an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on male fertility? The ACE2 connection. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E878–E880. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00183.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seymen C M. The other side of COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on male fertility. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1396–1402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shen Q, Xiao X, Aierken A. The ACE2 expression in Sertoli cells and germ cells may cause male reproductive disorder after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:9472–9477. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Illiano E, Trama F, Costantini E. Could COVID-19 have an impact on male fertility? Andrologia. 2020;52:e13654. doi: 10.1111/and.13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalra S, Bhattacharya S, Kalhan A. Testosterone in COVID-19 – Foe, Friend or Fatal Victim? Eur Endocrinol. 2020;16:88. doi: 10.17925/ee.2020.16.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paoli D, Pallotti F, Nigro G. Sperm cryopreservation during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44:1091–1096. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Temiz M Z, Dincer M M, Hacibey I. Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 in semen samples and the effects of COVID-19 on male sexual health by using semen analysis and serum male hormone profile: A cross-sectional, pilot study. Andrologia. 2021;53:e13912. doi: 10.1111/and.13912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pazir Y, Eroglu T, Kose A. Impaired semen parameters in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection: A prospective cohort study. Andrologia. 2021;53:e14157. doi: 10.1111/and.14157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li H, Xiao X, Zhang J. Impaired spermatogenesis in COVID-19 patients. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo T-H, Sang M-Y, Bai S. Semen parameters in men recovered from COVID-19. Asian J Androl. 2021;23:479–483. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_31_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erbay G, Sanli A, Turel H. Short-term effects of COVID-19 on semen parameters: A multicenter study of 69 cases. Andrology. 2021;9:1060–1065. doi: 10.1111/andr.13019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koç E, Keseroğlu B B. Does COVID-19 Worsen the Semen Parameters? Early Results of a Tertiary Healthcare Center. Urol Int. 2021;105:743–748. doi: 10.1159/000517276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Best J C, Kuchakulla M, Khodamoradi K. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 in Human Semen and Effect on Total Sperm Number: A Prospective Observational Study. World J Mens Health. 2021;39:489. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.200192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pan F, Xiao X, Guo J. No evidence of severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 in semen of males recovering from coronavirus disease 2019. Fertil Steril. 2020;113:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song C, Wang Y, Li W. Absence of 2019 novel coronavirus in semen and testes of COVID-19 patients†. Biol Reprod. 2020;103:4–6. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioaa050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li D, Jin M, Bao P. Clinical Characteristics and Results of Semen Tests Among Men With Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208292. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paoli D, Pallotti F, Colangelo S. Study of SARS-CoV-2 in semen and urine samples of a volunteer with positive naso-pharyngeal swab. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1819–1822. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Safrai M, Reubinoff B, Ben-Meir A. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine does not impair sperm parameters. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.30.21255690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gonzalez D C, Nassau D E, Khodamoradi K. Sperm Parameters Before and After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326:273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang C, Zhou S-F, Gao L-D. Risks associated with cryopreserved semen in a human sperm bank during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ruan Y, Hu B, Liu Z. No detection of SARS-CoV-2 from urine, expressed prostatic secretions, and semen in 74 recovered COVID-19 male patients: A perspective and urogenital evaluation. Andrology. 2021;9:99–106. doi: 10.1111/andr.12939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burke C A, Skytte A B, Kasiri S. A cohort study of men infected with COVID-19 for presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in their semen. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:785–789. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kayaaslan B, Korukluoglu G, Hasanoglu I. Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 in Semen of Patients in the Acute Stage of COVID-19 Infection. Urol Int. 2020;104:678–683. doi: 10.1159/000510531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma L, Xie W, Li D. Evaluation of sex-related hormones and semen characteristics in reproductive-aged male COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2021;93:456–462. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pavone C, Giammanco G M, Baiamonte D. Italian males recovering from mild COVID-19 show no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen despite prolonged nasopharyngeal swab positivity. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:560–562. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-00344-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nieschlag E, Schlatt S, Kliesch S, Behre H M. 5. Aufl. Berlin, Heidelberg:: Springer;; 2012. WHO-Laborhandbuch zur Untersuchung und Aufarbeitung des menschlichen Ejakulates. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carto C, Nackeeran S, Ramasamy R. COVID-19 vaccination is associated with a decreased risk of orchitis and/or epididymitis in men. Andrologia. 2021 doi: 10.1111/and.14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.World Health Organization . Geneva: WHO; 2010. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of human Sperm. 5th ed. [Google Scholar]