Abstract

Therapeutic interventions of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury to attenuate liver dysfunction or multiple organ failure following liver surgery and transplantation remain limited. Here we present an innovative strategy by integrating a platinum nanoantioxidant and inducible nitric oxide synthase into the zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 based hybrid nanoreactor for effective prevention of ischemia-reperfusion injury. We show that platinum nanoantioxidant can scavenge excessive reactive oxygen species at the injury site and meanwhile generate oxygen for subsequent synthesis of nitric oxide under the catalysis of nitric oxide synthase. We find that such cascade reaction successfully achieves dual protection for the liver through reactive oxygen species clearance and nitric oxide regulation, enabling reduction of oxidative stress, inhibition of macrophage activation and neutrophil recruitment, and ensuring suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. The current work establishes a proof of concept of multifunctional nanotherapeutics against ischemia-reperfusion injury, which may provide a promising intervention solution in clinical use.

Subject terms: Preclinical research, Nanomedicine, Biomaterials, Animal disease models, Biomedical engineering

Pharmacological interventions against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury remain limited. Here, the authors provide a nanotherapeutics-based solution combining reactive oxygen species scavenging and nitric oxide modulation.

Introduction

Currently, liver resection and transplantation have been widely used in the clinic to treat various liver diseases such as intrahepatic bile duct stones, liver trauma, tumors and other diseases1. During the surgery, liver ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) occurs due to the cessation and restoration of blood supply, which may result in an acute inflammatory response, severe liver damage, and even multiple organ failure and death2–4. Current intervention strategies for hepatic IRI include ischemic preconditioning, pharmacological agents preconditioning, gene therapy, and so on5,6. However, due to the complicated pathophysiological processes of IRI, there is so far no effective solution for the prevention and intervention of IRI in the clinic.

Hepatic IRI is a pathological process involving multiple factors, including acidosis, oxidative stress, intracellular calcium overload, and activation of macrophages and neutrophils caused by hypoxic metabolism2,7. Pharmacological interventions such as supplementation of antioxidants to reduce the oxidative stress have been explored to minimize the risk of liver damage8–10. The FDA approved drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an antioxidant and glutathione inducer indicated for the treatment of fulminant liver failure due to paracetamol overdose11. NAC has also been utilized for ameliorating hepatocyte damage in IRI experimental models, while more clinic outcome data is required before the routine use of NAC12,13. Recently, accumulating evidence reveals that nitric oxide (NO) plays diverse roles in modulating cell behaviors and NO-releasing materials have been designed for potential therapeutic applications14–18. In particular, it has been reported that the administration of inhaled NO, nitrite or NO donor drugs could attenuate ischemia/reperfusion injury during the liver surgery and accelerate the restoration of liver function19–21. However, challenges such as short half-life of NO, ambiguous therapeutic effect and drug tolerance remain and further improvements are needed17,22–24.

Since the discovery of Fe3O4 nanoparticles as the peroxidase mimics25, a variety of nanomaterials capable of mimicking the functions of natural enzymes, namely nanozymes, have attracted considerable interest26–28. Owing to advantages in stability, low cost, and recyclability, nanozymes have been widely used in areas of chemistry, biology, and medicine29–32. Among these nanozymes, several nanomaterials have displayed promising effect on the elimination of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which could be employed as biomimetic antioxidants to regulate ROS homeostasis31,33–36. In particular, platinum nanoparticles (Pt NPs) as the substitute of natural enzymes for the treatment of oxidative stress-related diseases have gained growing interest, owing to their cytocompatibility and enzyme-like catalytic ability37–39. Pt NPs display the catalase (CAT)-like properties that decompose hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into H2O and oxygen (O2). It was also reported they could scavenge superoxide anion (•O2−), similar to superoxide dismutase (SOD)40. In addition, nanozyme-catalyzed cascade reactions are intriguing for versatile biomedical applications41–45. For example, Li et al. integrated the artificial Au nanoparticle (NP) nanozyme and natural ATP synthase into hollow silica microspheres for mitochondria-mimicking oxidative phosphorylation41. In the designed natural-artificial hybrid architecture, the Au NPs could convert glucose into gluconic acid in the presence of oxygen (O2) and the resulting transmembrane proton gradient facilitated the production of ATP catalyzed by ATP synthase. Nanozyme-involved cascade reactions exhibit great benefits in reducing the diffusion barriers, minimizing intermediate decomposition and enhancing local concentrations of reactants, thereby improving the intercommunication and efficiency of catalytic reactions46–48.

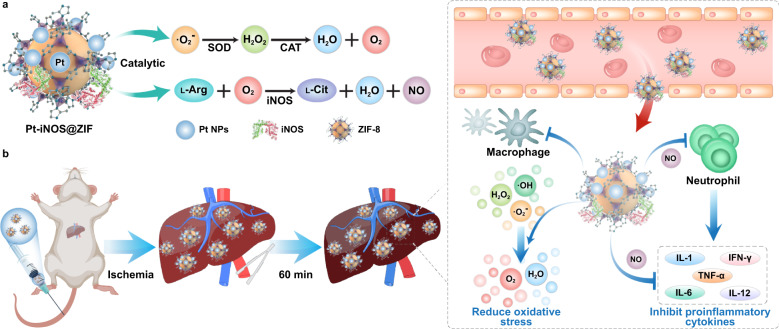

In this work, we rationally design a nanozyme-containing biomimetic cascade system to achieve simultaneous NO generation and noxious ROS depletion for effective prevention of IRI, given the endogenous synthesis of NO produced from ʟ-Arginine (ʟ-Arg) by the catalysis of nitric oxide synthases (NOS). To make full use of the inherent advantages of nanozymes and natural enzymes, ultrasmall platinum nanoparticles (Pt NPs) with SOD/CAT-like properties and induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were integrated into the zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) carriers to form a safe and effective nanoreactor (Pt-iNOS@ZIF). The process of eliminating ROS by Pt NPs nanozyme generated oxygen, which further promoted the production of NO via the catalysis of iNOS in the presence of ʟ-Arg (Fig. 1a). In the biological context, Pt-iNOS@ZIF was found to greatly reduce oxidative stress-induced damage, inhibit cell apoptosis, and reduce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to effective intervention of hepatic IRI (Fig. 1b). Overall, the designed nanoreactor not only improves the targeting and bioavailability of NO, but also exhibits dual protective effects via ROS elimination and NO modulation, thereby offering a promising strategy to protect the liver from IRI.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of hepatic IRI prevention performance by Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor.

a Illustration of the designed Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor. The synthesized Pt nanozyme with SOD/CAT-like properties could scavenge overexpressed ROS induced by IRI to generate O2. Then iNOS enzyme could further catalyze ʟ-Arginine (ʟ-Arg) and O2. to produce ʟ-Citrulline (ʟ-Cit) and NO. b Schematic of the hepatic IRI generation and treatment with the Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor. It can reduce oxidative stress and inhibit proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in effective prevention the liver from IRI.

Results

Design, synthesis, and characterization of Pt-iNOS@ZIF

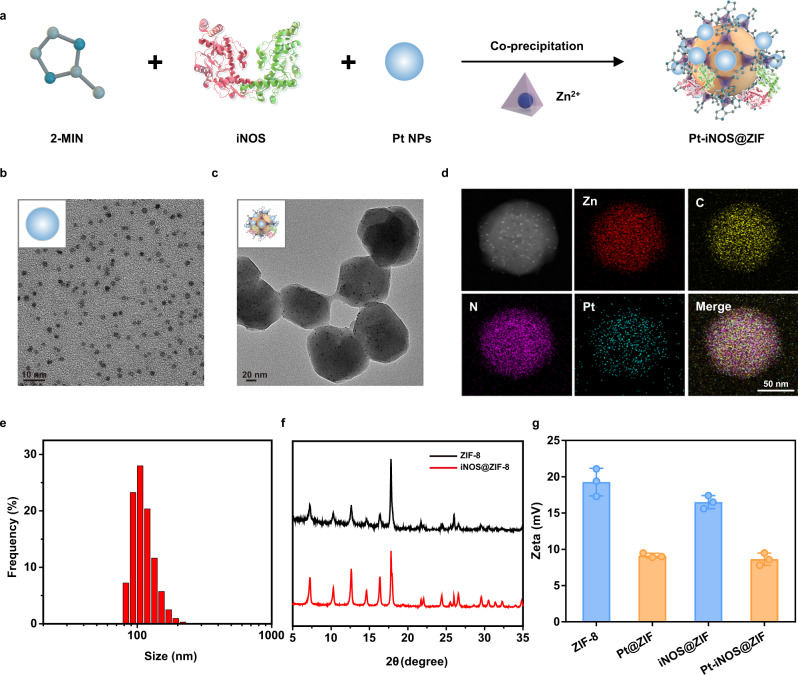

In this study, the natural-artificial hybrid nanoreactor was designed and synthesized. First, ultrasmall polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated Pt NPs were successfully synthesized according to the reported method49. Then the co-precipitation approach was applied to simultaneously embed enzyme molecules (iNOS) and Pt NPs into the ZIF-8 supporting matrix (Fig. 2a). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and elemental mapping results clearly indicated that the obtained Pt NPs had an average size of ~3 nm with a narrow size distribution. Interestingly, the Pt NPs could be effectively deposited in the whole ZIF-8 NPs during the co-precipitation process (Fig. 2b–d). The as-prepared Pt-iNOS@ZIF displayed an average size distribution of 99.7 ± 9.0 nm by dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement (Fig. 2e). Next, TEM results suggested the loading content of Pt element gradually increased with the increasing feeding amount of Pt NPs (Pt:Zn ratios of 1:250, 1:50, and 1:10) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The optimal loading content of Pt in Pt-iNOS@ZIF with good dispersibility in aqueous solutions was calculated to be 2.3% (wt%) by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). To investigate the process of enzyme embedding into ZIF-8, the iNOS@ZIF NPs were synthesized, which displayed similar morphology with ZIF-8 NPs. X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern suggested no significant difference in the crystal structure before and after the enzyme encapsulation (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, Fig. 2g showed that there were close zeta potential values before and after the iNOS encapsulation, further validating the enzyme embedding, rather than surface absorption processes50. In the absence of iNOS, the ZIF-8 NPs had an average size of around 69 ± 8 nm. With the addition of iNOS, the size of enzyme-encapsulated NPs gradually increased, which is likely attributed to the protein-mediated aggregative growth. However, continuous addition of iNOS may result in the increased NP size along with the polydispersity and aggregation (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, we fixed the loading content at around 6.8% with a relatively uniform size less than 100 nm, which is beneficial for cell internalization further in vivo applications. Additionally, the stability of Pt-iNOS@ZIF under biological conditions were carefully evaluated by monitoring the morphology, size and cargo release (Pt and iNOS), respectively. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, TEM results indicated that the nanoparticles maintained the integrity at 24 h, while the hydrodynamic diameter gradually increased over time and reach a plateau after incubation for about 6 h. The increase in size was likely attributed to the complexation between proteins in serum and zinc ions from the surface of the composite. Due to the pH-responsive nature of ZIF-8 structure, substantial release of both iNOS (77.3%) and Pt (54.2%) was observed under acidic conditions (pH 6.5) (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 2. Preparation and characterizations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor.

a Synthetic procedure of Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor. b, c TEM images of the synthesized Pt NPs and Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor. d, e Elemental mapping and size distribution of Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor analyzed by dynamic laser scattering (DLS), scale bar: 50 nm. f X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of ZIF-8 and iNOS@ZIF-8 NPs. g Zeta potentials of different NPs (ZIF-8, Pt@ZIF, iNOS@ZIF and Pt-iNOS@ZIF) (n = 3 independent samples). Experiments were performed twice (d) or three times (b, c), with similar results. Data presented as means ± s.d.

In vitro performance

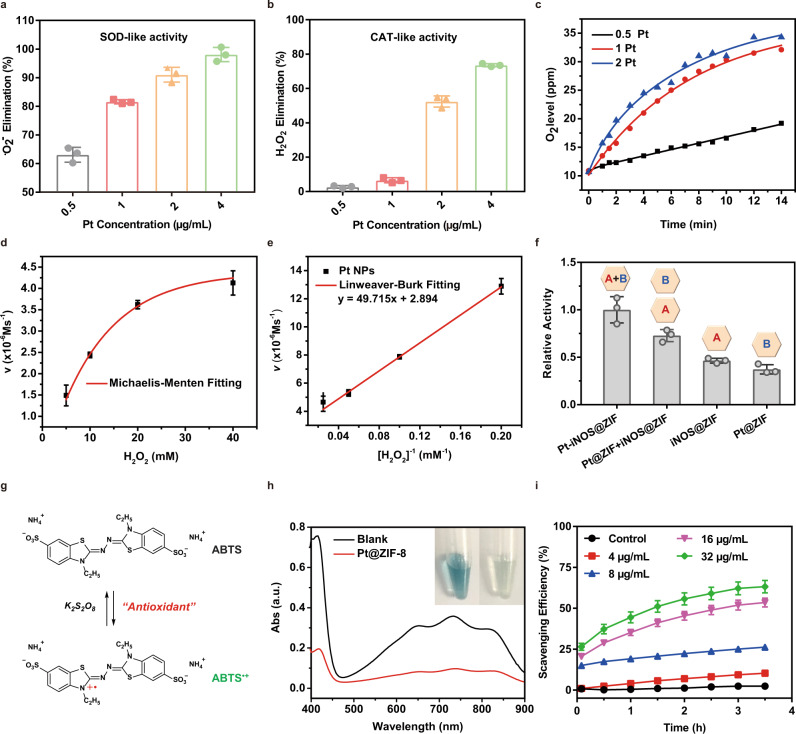

Firstly, the enzyme-like catalytic activities of Pt NPs were examined by superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay kit and hydrogen peroxide assay kit, respectively. SOD is known to catalyze the superoxide anion (•O2−) to generate oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), while catalase (CAT) is able to decompose H2O2 into H2O and O2. By following the commercially available standard protocols, the inhibition rate of •O2− and H2O2 was obtained. Results demonstrated the elimination ability of both •O2− and H2O2 increased with the increase of Pt NPs concentrations (Fig. 3a, b). To further verify the SOD/CAT mimic capability, the time course of O2 generation was monitored by dissolved oxygen probe. In the presence of Pt NPs, the O2 level gradually increased over time and the addition of more Pt NPs would undoubtedly accelerate the generation of O2 (Fig. 3c). Moreover, the Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) were determined to be 172 mM and 3.46 × 10−6 M s−1, given the Michaelis-Menten curves and Lineweaver-Burk plot (Fig. 3d, e). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrated that Pt NPs exerted both excellent SOD and CAT-like activities, enabling effective elimination of •O2− and H2O2.

Fig. 3. In vitro catalytic performance.

a, b ROS scavenging activities of Pt NPs with SOD-like and CAT-like properties. c Concentration-dependent generation of O2 in the presence of Pt nanozyme at different concentrations (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 µg/mL). d, e Michaelis-Menten steady-state kinetics of O2 generation from the decomposition of H2O2 by Pt NPs. f The normalized enzymatic activities of Pt-iNOS@ZIF, Pt@ZIF + iNOS@ZIF, iNOS@ZIF and Pt@ZIF at 12 h time point. The inside symbol [A] = iNOS, [B] = Pt. g The antioxidant principle of the ABTS assay. h Absorbance and pictures of ABTS radicals with or without treatment of Pt-iNOS@ZIF at 3 h time point. i Analysis of the scavenging efficiency of ABTS radicals by different concentrations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF. For 3a, b, d–f, i, n = 3 independent samples, data presented as means ± s.d.

Given the consumption of O2 during the synthesis of NO, we subsequently evaluated whether the generated O2 could continuously promote the oxidization of ʟ-Arg into NO. As shown in Fig. 3f, the co-assembled nanoreactor exhibited higher enzymatic activity compared to that of individual enzyme nanoplatform (Pt@ZIF or iNOS@ZIF) or the mixture of two separate systems (Pt@ZIF + iNOS@ZIF) at a fixed time-interval (12 h), clearly demonstrating that the spatial confinement of Pt and iNOS catalyst in the engineered ZIF-8 scaffold enhanced the efficiency of the biocatalytic cascade. To evaluate the overall antioxidant capacity of the as-prepared Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor, the 2,2′ -azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay was performed based on the reduction of ABTS•+ radicals by antioxidants (Fig. 3g). As shown in Fig. 3h, the ABTS•+ radicals with blue color exhibited obvious absorbance decrease and discoloration in the presence of Pt-iNOS@ZIF. Also, the radical scavenging efficiency is positively correlated with the nanoparticle concentrations, implying favorable antioxidant ability of Pt-iNOS@ZIF to scavenge ATBS radicals (Fig. 3i).

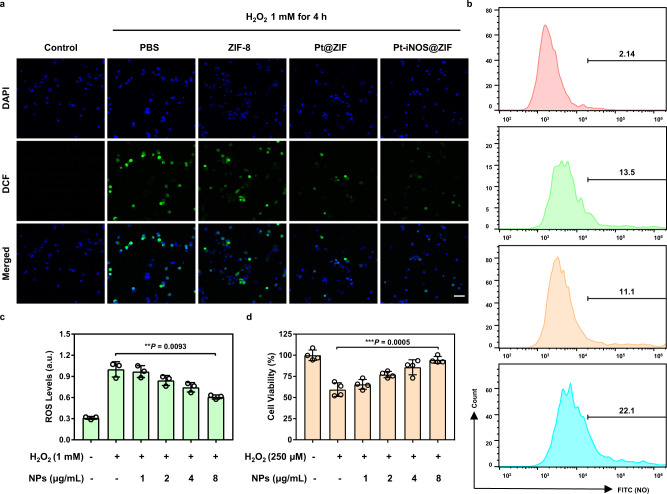

Cellular evaluation of Pt-iNOS@ZIF

Next, we examined the antioxidant effects of Pt-iNOS@ZIF in primary mouse hepatocyte FL83B cells. H2O2 was utilized to stimulate intracellular oxidative stress and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was applied as ROS indicator. As shown in Fig. 4a, strong green fluorescence signals were observed with the addition of H2O2 as compared to the control group without H2O2 treatment. When treated with Pt@ZIF or Pt-iNOS@ZIF, the intracellular fluorescence signals were remarkably decreased, while there was minimal fluorescence disturbance in the ZIF-8 NPs treated group. Quantitative analysis by flow cytometry revealed reduced intracellular ROS level (51.4%) in (Pt@ZIF + H2O2)-treated cells as compared to that in H2O2-stimulated cells (59.1%), suggesting the ROS scavenging effect from Pt nanozyme. As comparison, Pt-iNOS@ZIF treated group remarkably decreased ROS level to around 22.8% in H2O2-pretreated cells (Supplementary Fig. S6). Moreover, the Pt-iNOS@ZIF exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of ROS generation (Fig. 4c). Subsequently, intracellular NO levels were evaluated by the nitric oxide indicator (DAF-FM diacetate) via flow cytometry analysis and Pt-iNOS@ZIF + H2O2 group exhibited stronger fluorescence signals than the other groups (Fig. 4b). Then the protective effect of Pt-iNOS@ZIF against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in cells was evaluated by the standard methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay. Unsurprisingly, H2O2 (250 μM) treatment resulted in about 41% cell death after incubation for 24 h, while the addition of Pt-iNOS@ZIF exhibited concentration-dependent increase of the cell viability, implying its protective effect against oxidative damage (Fig. 4d). Compared to the Pt@ZIF or iNOS@ZIF alone, Pt-iNOS@ZIF exhibited improved therapeutic effect. Although simultaneous addition of Pt@ZIF and iNOS@ZIF achieved similar protective effect, the coformulation ensured equal biodistribution, which is valuable for the tandem reaction-based therapy (Supplementary Fig. S7). Moreover, all designed NPs would induce negligible cell death in hepatocytes, HEK 293 cells and macrophage cells (up to 40 µg/mL), suggesting their good biocompatibility and minimum side effect from the nanoformulas themselves (Supplementary Fig. S8-S12). Collectively, all these results demonstrated that Pt-iNOS@ZIF-8 NPs could effectively alleviate oxidative stress and rescue cells from ROS-induced damage.

Fig. 4. Antioxidant and cell protection activities in FL83B cells.

a Fluorescence images of ROS levels in H2O2-stimulated hepatocytes pretreated with PBS, ZIF-8, Pt-ZIF and Pt-iNOS@ZIF NPs (8 μg/mL). Cells were stained with DCFH-DA (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue) after 4 h incubation. Experiments were performed three times with similar results. Scale bar: 50 μm. b Flow cytometry analysis of NO levels with various treatments. The values indicate the percentage of cells staining with NO indicators out of total cells in the selected gate. c ROS levels H2O2-stimulated hepatocytes pretreated with different concentrations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF (0, 1, 2, 4, 8 μg/mL) (n = 3 biologically independent samples). d Cell viability in hepatocytes stimulated with H2O2 for 24 h in the presence of Pt-iNOS@ZIF (0, 1, 2, 4, 8 μg/mL) (n = 4 biologically independent samples). For c, d data presented as means ± s.d. one-tailed unpaired t-test. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

In vivo imaging, biodistribution and pharmacokinetics

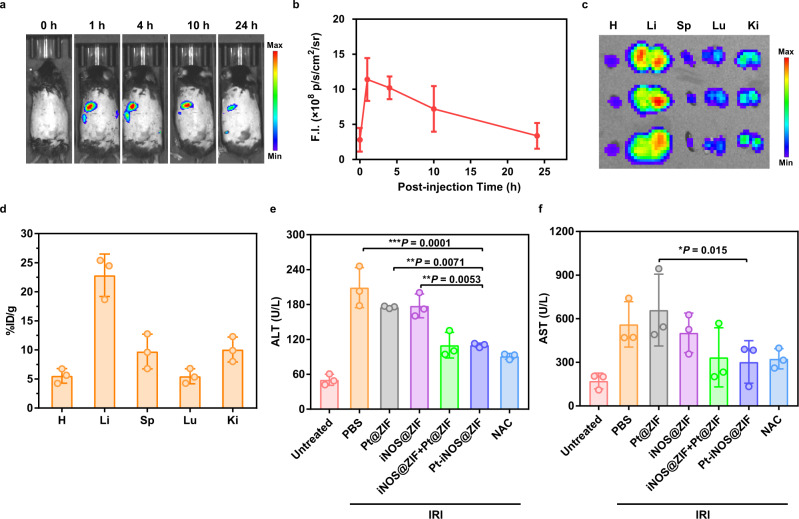

In comparison with small molecular drugs, various types of nanomaterials have intrinsic advantages of passive targeting and accumulation in the liver. To evaluate the biodistribution and liver accumulation of Pt-iNOS@ZIF in living systems, Cy5 labeled iNOS enzyme was applied to form Pt-iNOS (Cy5)@ZIF and real-time fluorescence imaging was carried out in mice after intravenous injection (i.v.) of the NPs. As shown in Fig. 5a–c and Supplementary Fig. S13, there was an obvious increase of fluorescence signals at 1 h post injection (p.i.) and semi-quantitative analysis revealed that the NPs could remain in the liver for up to 10 h (7.2 × 108 p/s/cm2/sr) and were gradually cleared from the liver by 24 h (3.4 × 108 p/s/cm2/sr) p.i. Moreover, the pharmacokinetics and ex vivo biodistribution in major organs at 24 h were verified by ICP-OES. The results demonstrated that the NPs were able to efficiently accumulate in the liver (22.84 ± 3.65%ID g−1), serving as an optimal candidate for IRI intervention (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. S14 and Table 1).

Fig. 5. In vivo performance.

a Representative in vivo fluorescence images of C57BL/6 mice at 1, 4, 10, and 24 h p.i. of Pt-iNOS@ZIF (n = 3). b Quantitative ROI assays of the fluorescence intensity in mice at designated time points. c Ex vivo fluorescence images of major organs at 24 h p.i. H: heart, Li: liver, Sp: spleen, Lu: lung, Ki: kidney. d Biodistribution of Pt-iNOS@ZIF in major organs at 24 h p.i. evaluated by ICP-OES. e, f Serum ALT and AST levels in mice after 60 min of ischemia and 12 h of reperfusion from each group. For 5b, d–f, n = 3 biologically independent animals. Data presented as means ± s.d. P values were calculated by ANOVA F-test, each comparison stands alone. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Protective effect in a hepatic IRI model

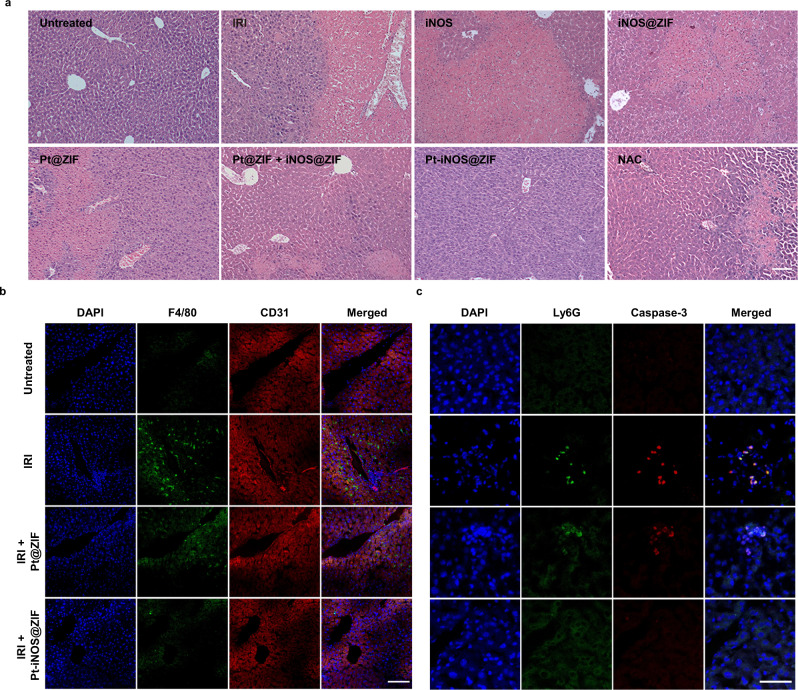

Based on the promising antioxidant effect of Pt-iNOS@ZIF, we further investigated the feasibility of the protective effect against IRI in a murine model. C57BL/6 mice were treated with different nanoplatforms for 12 h before the clamping of porta hepatis. The untreated group underwent the same procedure, but without vascular occlusion. After 60 min of ischemia and subsequent reperfusion, blood and liver samples were collected and liver functions at 12 h after surgery were further analyzed. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were applied as indicators of liver damage. To better evaluate the therapeutic effect, the antioxidant drug NAC was administered intravenously for comparison before surgery. Compared to the untreated control group, the IRI mice group displayed significant increase of ALT and AST levels, indicating alleviated liver injury. When the IRI mice were pretreated with different types of NPs, the Pt-iNOS@ZIF treated IRI mouse group had remarkably reduced ALT and AST levels compared to those in Pt@ZIF or iNOS@ZIF treated groups. Moreover, Pt-iNOS@ZIF at the dosage of 2 mg/kg achieved comparable therapeutic effect to that of NAC therapy (150 mg/kg), clearly demonstrating its advantage in intervention of liver injury (Fig. 5e–f and Supplementary Fig. S15). To further evaluate the therapeutic efficacy, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in liver tissues and blood test were performed after pretreatment with various NPs in IRI mice. As expected, severe hepatocyte necrosis and cytolysis was observed in the PBS-treated IRI group after 12 h. The ZIF-8 NPs, Pt NPs and iNOS treated groups displayed indistinguishable difference in the liver injury. iNOS@ZIF and Pt@ZIF slightly attenuated the damage, while it seemed there was no significant difference between the mixture of two separate system (Pt@ZIF + iNOS@ZIF) and co-assembled Pt-iNOS@ZIF. Given the complex physiological processes and multiple regulation factors in IRI, the mechanisms of action will need to be further explored, yet these results do not diminish the importance of coformulation with respect to simple operation and equal biodistribution (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Figs. S16-S17). Overall, the results were consistent with the trend of ALT and AST levels. Besides the therapeutic effectiveness of the designed nanomedicine, the safety in living systems is also important for further potential clinic applications. Hemolysis test (24 h p.i.) and H&E staining of major organs after injection of Pt-iNOS@ZIF for 7 days were evaluated (Supplementary Fig. S18-S21). All results showed Pt-iNOS@ZIF exhibited excellent biocompatibility and could be considered as an ideal candidate for the prevention of IRI.

Fig. 6. H&E and Immunofluorescence staining on liver tissues.

a H&E staining of liver tissues from each group (Untreated, PBS, iNOS, iNOS@ZIF, Pt@ZIF, Pt@ZIF+iNOS@ZIF, Pt-iNOS@ZIF, NAC) after 60 min of ischemia and 12 h of reperfusion. Scale bar: 100 µm. b Immunofluorescence staining of liver tissues with various treatments by using DAPI (blue) for nuclear staining, anti-F4/80 antibody (green) as monocyte/macrophage marker, and anti-CD31 antibody (red) as an endothelial marker from each group. Scale bar: 100 µm. c Enlarged images of immunofluorescence staining with various treatments by using DAPI (blue) for nuclear staining, anti-Ly6G antibody (green) as neutrophil marker and anti-caspase-3 antibody (red) as a cell apoptosis marker. Experiments were performed three times (a–c) with similar results. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Liver IRI is a pathophysiological event and oxidative stress is considered as one essential mechanism. To further obtain visual evidence for cellular events, immunofluorescence imaging was performed on liver tissues. Results indicated that hepatic IRI led to obvious activation of monocytes/macrophages compared to the untreated group. The designed Pt@ZIF NPs can slightly inhibit the activation of macrophages, likely due to its ROS scavenging effect (Fig. 6b). By employing both ROS scavenging derived from Pt nanozyme and NO-based modulating effect, Pt-iNOS@ZIF treated mice exhibited minimal activation of monocyte/macrophages. Similarly, the Pt-iNOS@ZIF treated group also greatly suppressed the recruitment of neutrophils and caspase activities for preventing cells from apoptosis compared to the IRI group (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. S22 and Table 2). Taken together, all these findings indicated that the preconditioning of Pt-iNOS@ZIF could inhibits IRI-induced macrophage activation, neutrophil accumulation, and subsequent apoptotic processes.

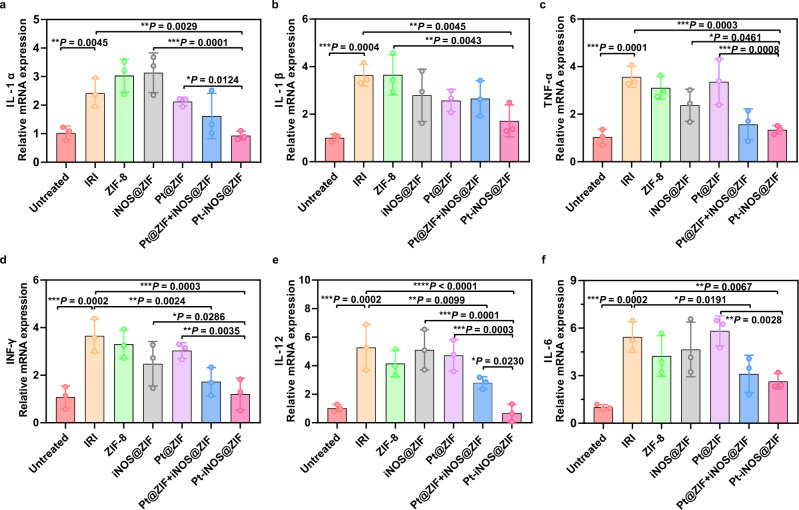

Encouraged by the above results, we further investigated the anti-inflammatory activities of the designed Pt-iNOS@ZIF, the expression of mRNAs for the pro-inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-12 (IL-12), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon gamma (INF-γ) were measured from each group. As shown in Fig. 7, the levels of these pro-inflammatory cytokines were significantly increased in the hepatic IRI group, while they were reduced to relatively normal ranges in Pt-iNOS@ZIF treated IRI group. TNF-α is one intensively studied cytokine in response to inflammatory and immunomodulatory stimuli, and is a regulator responsible for the production of ROS. Also, IL-1 can facilitate the synthesis of TNF-α by Kupffer cells and recruitment of neutrophils51. IFN-γ produced mainly by activated natural killer T cells will promote Kupffer cells or dendritic cell activation. Activation of Kupffer cells and neutrophils in turn induces the release of various chemokines and cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, etc. which further activates local immune cells, recruits circulating immune cells and aggravates liver damage52. Taken together, these results indicated that Pt-iNOS@ZIF preconditioning would significantly suppress the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, which is generally involved in the initiation and propagation of IRI.

Fig. 7. Anti-inflammatory activities in hepatic IRI.

Relative expression of mRNAs for cytokines of IL-1α (a), IL-1β (b), INF-γ (c), IL-12α (d), TNF-α (e), IL-6 (f) (n = 3 biologically independent animals). Data presented as means ± s.d. from three independent replicates, and P values were calculated by ANOVA F-test, each comparison stands alone. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

IRI include a series of complicated processes including the restriction of blood supply, subsequent restoration and reoxygenation, during which the imbalance of metabolic supply, inflammation and oxidative damage are involved. Additionally, the innate and adaptive immune responses will be activated, resulting in cell damage and organ dysfunction2. Oxidative stress is considered to play a pivotal role in ischemia and reperfusion damage. It has been reported that ROS scavenging via supplementation of antioxidants has the ability of diminishing oxidative stress and ensuing organ injury53. SOD can promote the conversion of •O2− to O2 and H2O2. Also, H2O2 can be decomposed to H2O and O2 under the catalysis of CAT. Therefore, both enzymes exhibited beneficial actions by accelerating the detoxification of ROS in IRI. However, the short half-life of these natural proteases in the body (half-life of SOD is about 6 min), difficulty of cell uptake, and low delivery efficiency hinder their further applications8. Besides, NO, one of therapeutic gaseous molecules, has multiple regulatory functions, such as improving the microcirculation, suppressing caspase activities, and inhibiting neutrophil infiltration and platelet aggregation54. NO-based therapy has been applied for pulmonary hypertension and cardiopulmonary disorders for many years55, and its therapeutic effect on protection liver from IRI has increasingly received considerable attention20,56.

In this study, we successfully synthesized ultrasmall Pt NPs, which could act as SOD and CAT mimics with excellent ROS scavenging capacity. In order to further enhance the therapeutic efficacy, NO-based therapy is incorporated by integrating the iNOS enzyme and Pt nanozyme into ZIF-8 architecture to achieve synergistic effect. Co-precipitation method was applied to obtain the hybrid nanoreactor, ensuring efficient embedding of iNOS into ZIF-8 during the process of nanoparticle formation. Such design not only prevents natural enzymes from inactivation and degradation in the body, but also promotes the molecular diffusion and intercommunication due to the intrinsic porous feature and large surface areas of metal-organic frameworks57,58. More importantly, as the synthesis of NO is O2-dependent, the generated O2 by Pt catalysis will further improve the iNOS-mediated cascade reaction activities. After the ischemia and reperfusion, the restoration of blood flow will cause the release of ROS, activation of macrophage cells and recruitment of neutrophils, which further leads to the release of large amount of chemokines and cytokines2. Apart from the ROS elimination by Pt nanozyme, protective actions of NO during ischemia and reperfusion are probably attributed to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. The prepared Pt-iNOS@ZIF nanoreactor could maintain ALT and AST levels of IRI mice in the relatively normal range. Additionally, it greatly suppressed the activation of macrophages cells, along with the minimized infiltration of neutrophils and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which eventually attenuated the liver damage caused by IRI. Considering the pathological process of induction of oxidative stress in various types of IRI, the cytoprotective effects of this approach in the liver may be applicable to other organ systems, such as heart and kidneys. It should be noted that nitric oxide may display both protective and toxic effects, depending on the NO levels, NO source, and timing of administration. Hence the therapeutic window for IRI in different organs should be carefully evaluated.

In summary, we developed an ZIF-8-based hybrid nanoreactor, which encapsulated the Pt nanozyme and natural enzyme iNOS, for protecting the liver from IRI. By using the excessive ROS generated during hepatic ischemia/reperfusion as a stimulus, the Pt nanozyme with SOD/CAT-like properties could scavenge •O2− and H2O2 to produce O2, which can further react with ʟ-Arg to form NO under the catalysis of iNOS enzyme. Such designed cascade reaction successfully achieved the ROS scavenging (•O2− and H2O2) and NO production, which effectively reduced oxidative stress and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the process of hepatic ischemia and reperfusion. So far, the pharmacological agents in routine clinical use to prevent liver IRI are rare, likely due to their short blood circulation time, poor solubility of most antioxidant and anti-inflammatory drugs and non-specific biodistribution after systemic administration. Our designed nanoformulation enables effective therapeutic outcome with a relatively low dosage, which is likely attributed to the improved pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution. More importantly, the intrinsic ROS in the pathological regions as the reactant initiate the catalytic reaction, thus conferring high specificity for mitigating side effects. In-depth understanding of the molecular mechanisms of IRI will be of great importance in improving current treatment regimens and developing innovative intervention strategies. Besides, efforts should also be made on the combination of multiple drugs, which will improve the effectiveness, success of liver surgery and survival rate of patients. Overall, this study may not only provide a promising solution of multifunctional nanotherapeutics for the treatment of IRI, but also shed light on dual protection mechanism of ROS clearance and NO regulation, which is beneficial to advance further clinical applications in hepatic IRI.

Methods

Materials

Hexachloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (H2PtCl6‚ 6H2O), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), 2-methylimidazole (2-MIN), nitric oxide synthases (iNOS) enzyme, ʟ-Arginine, 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT), 2,2’-Azino-bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) (ABTS), SOD assay kit, and hydrogen peroxide assay kit were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The Griess assay kit was purchased from Promega Corporation (U.S.A). Singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG), Hoechst 33342 solution, and DAF-FM Diacetate were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, U.S.A.). The primer pairs for indicated gentes were provided by Shanghai Personal Gene Technology Co., Ltd. China. All other ere purchased from Sigma without further purification.

Characterizations

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired on the FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope. Elemental mapping was acquired on the scanning transmission electron microscope (JEM-3200FS, JEOL, Japan). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were performed at a SZ-100 nano particle analyzer (HORIBA Scientific). The XRD pattern was recorded on a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Germany), UV-Vis absorption spectrum was recorded on a Shimadzu UV-2501 spectrophotometer. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was used to quantify Zn and Pt concentrations. Fluorescence images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 780, Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo V10. Tissue and tumor samples for eosin (H&E) staining were prepared by Shanghai Weiao Biotechnology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China) and observed using a BX41 bright field microscopy (Olympus).

Syntheis of platnium nanoparticles (Pt NPs)

The ultra-small platinum nanoparticles were prepared according to the reported method with slight modification49: Briefly, in 10 mL of 1 mM hexachloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (H2PtCl6•6H2O) solution, 111.1 mg of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added. After stirring for 15 min, 200 µL freshly prepared sodium borohydride (NaBH4) solution (100 mM) was added and stirred for 12 h. The solution turned dark brown and Pt NPs were obtained for further use.

Syntheis of ZIF-8, Pt@ZIF, Pt-iNOS@ZIF Nanosystms

The ZIF-8 nanoparticles were synthesized according to the reported method50. Briefly,100 μL Zn(NO3)2•6H2O aqueous solution (0.5 M) was added into 900 μL 2-methylimidazole (2-MIN, 3.5 M) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The obtained product was collected by centrifugation (3500 × g, 10 min) and washed with water for three times. Similarly, nanoscale Pt@ZIF was synthesized by mixing the 50 µL Pt NP solution with 900 μL 2-methylimidazole, followed by the additon of Zn(NO3)2•6H2O, The resulting Pt@ZIF was redispersed in water for further use. To synthezie nanoscale Pt-iNOS@ZIF, 0.3 mg iNOS enzyme was incubated with 900 μL 2-MIN for 10 min at 30 °C followed by addition of zinc nitrate. For the synthesis of Pt-iNOS(Cy5)@ZIF, 0.5 mg cyanine 5 NHS ester (Lumiprobe) was reacted with iNOS (0.3 mg) in PBS solution for overnight. Then the product was dialyzed to remove excessive dye molecules. The obtained iNOS (Cy5) was used to prepare Pt-iNOS(Cy5)@ZIF by using the same method for the synthesis of Pt-iNOS@ZIF. After centrifugation and washing with water for three times, the obtained products were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

In the Eqs. 1–3, ; ω(Pt) is the loading content of Pt

NPs, ω(ZIF) is the loading content of ZIF-8 NPs. m(Pt)total is the total weight of Pt element in one Pt-iNOS@ZIF particle. The average number of Pt NPs in one Pt-iNOS@ZIF was calculated to be about 41.

Assays of SOD-like and CAT-like activities

To evaluate the Pt nanozyme properties, the superoxide anion scavenging activity was conducted with a SOD assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The hydrogen peroxide quenching activity was performed with the Amplex® red hydrogen peroxide assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). All expreiments were carried out according to the standard protocol. To monitor the O2 production, different concentrations of Pt NPs (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 µg/mL) were mixed with 10 mM H2O2 in PBS buffer (pH 7.4), the dissiolved oxygen levels over time were measured by a dissolved oxygen probe. To obtain the enzyme kinetic parameters, different concencentraions of H2O2 were incubated with Pt NPs (2.0 µg/mL) for 10 min, the Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) were determined as following equation: .

In vitro measurement of total antioxidant capacity

The ABTS•+ radical scavenging assay was applied to evaluate the total antioxidant capacity of Pt-iNOS@ZIF. Briefly, 7 mM ABTS in deionized water was prepared and reacted with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate overnight. Then the solution turned dark blue and ABTS radical cation (ABTS•+) was obtained. Next, 200 µL diluted solution was mixed with different concentrations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF for 5 min and the UV-Vis spectra were recorded. The radical scavenging efficiency was calculated based on the absorbance changes at 734 nm. The data were analyzed using Origin 2015 software

General methods for cell culture

The murine hepatocyte FL83B cells (ATCC, #CRL-2390) were grown in F12K media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibico), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. The human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK 293) (ATCC, #CRL-1573), Raw264.7 cells (ATCC, TIB-71), Kupffer cells (Thermal Fisher Scientific, RTKCCS) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, Gibico) supplemented with 10% FBS at 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

Intracellular ROS and NO measurements

Intracellular ROS levels were measured using 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as the ROS indicator and NO levles were measured using nitric oxide indicators (DAF FM Diacetate). 8 μg/mL different types of NPs (ZIF-8, Pt@ZIF, Pt-iNOS@ZIF) were added into cells and cultured for 2 h, followed by the treatment with H2O2 (1 mM) and incubated for another 4 h at 37 °C. Then, the cells were stained with DCFH-DA (10 μM) or DAF probe (5 μM) for 30 min. After removing the excessive probe, fluoresence images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). H33342 channel (λex = 408 nm), FITC channel (λex = 488 nm). Quantative ROS levels with dfferent concentrations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF treatment (1, 2, 4, 8 µg/mL) were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cell viability assay

FL83B and HEK 293 cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a density of 1.0 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h incubation, the fresh medium containing different concentrations of Pt-iNOS@ZIF (1, 2, 4, 8 µg/mL) were added and incubated for another 2 h before addition of H2O2 (250 μM). Then cells were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and the cytotoxicity was evaluated by the standard MTT assay. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured by the microplate reader.

Preparation of hepatic IRI model in mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were received from Zhejiang Experimental Animal Center and were fed with a standard diet and water. The animals were hosted in equipped animal facility with ambient temperature of 22 °C and humidity at 30–70%, under a dark/light cycle of 12 h. All animal laboratory operations were carried out according to the Guide of Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital. For hepatic IRI model preparation, the mice were fasted for 12 h before the surgical operation. After the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, they were placed on a heated surgical pad and the abdomen of the depilated mice was disinfected with iodophor solution. Then a midline laparotomy was performed to expose the portal triplet. The portal triplet was carefully lifted using a vessel forceps, and all structures in the portal triplet (hepatic artery, portal vein, and bile duct) were blocked using a microvascular clamp. The abdominal wall was covered with PBS-soaked gauze and the blocking process lasted 60 min. After 60 min, microvascular clamp was removed for reperfusion. Signs of the reperfusion can be observed by the immediate color change of the central lobe and the left lobe of the liver.

In vivo imaging and biodistribution

For the fluorescence imaging, 100 μL Cy5-labled nanocomposite (Pt-iNOS(Cy5)@ZIF, 2 mg/kg) solutions was intravenously injected into male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old). In vivo fluorescence imaging was recorded at 1, 4, 10 and 24 h p.i. on an IVIS Spectrum system. At 24 h post injection, the above mice were sacrificed, and major organs were collected and washed before optical imaging. The fluorescence intensity of livers was acquired from the analysis of the region of interest (ROI) using a Living Image software. Moreover, the ex vivo biodistribution in major organs at 24 h was also measured by ICP-OES. The organs were weighted, and the percentage of injected dose per gram (%ID g−1) of tissue were calculated as the following equation: . The total injected does is 100 µg/mL. For pharmacokinetic studies, Pt-iNOS@ZIF was intravenously injected into mice and the blood samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 4, 12, and 24 h. Then blood samples were centrifuged at 10000 x g for 10 min to obtain the plasma. Then the supernatant was digested by aqua regia and the amount of Pt was quantified by ICP-MS.

Protective effect in a hepatic IRI model

The mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5) different formulations: (1) Untreated, (2) PBS + IRI, (3) ZIF-8 + IRI, (4) Pt NPs + IRI, (5) Pt@ZIF + IRI, (6) Pt-iNOS@ZIF + IRI. Nanoformulations (2 mg/kg) in each group were intravenously injected 12 h before surgical operation. After 12 h induction of the hepatic IRI model in mice, the blood was collected for biochemical analysis. Liver and kidney functions were evaluated by blood tests of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels (Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Center of Drug Safety Evaluation Research, CDSER, SIMM). The left liver lobes were dissected for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence staining

Frozen tissue sections were prepared and covered with OCT media. Then the liver tissue sections were fixed with zinc fixative solutions for 10 min. After rinsing slides with PBS for 3 times, the liver tissues were further treated with 2% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Then 100 µL blocking buffer (10% FBS in PBS) was added onto tissues for 1 h. Antibodies including F4/80 Monoclonal Antibody (BM8), FITC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #11-4801-85, 1:100), Alexa Fluor® 594 anti-mouse CD31 Antibody (Biolegend, #102520, 1:100), anti-mouse Ly6G/Ly6C (Gr-1) (BioXcel, #BE0075, 1:200) and Anti-Caspase-3 antibody (Abcam, #ab13847, 1:200) were diluted and added on slides and incubated for overnight at 4 °C. To stain the secondary antibody, slides were washed and incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 594) (Abcam, #ab150080, 1:200) or Goat Anti-Rat IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488) (Abcam, #ab150157, 1:200) for 1 h. After that, the slides were rinsed with PBS and mounted with DAPI-containing mounting solution. Fluorescence images were acquired via confocal microscopy.

Biocompatibility analysis

To evaluate the biocompatibility of nanoparticles, liver and kidney functions were assessed in healthy mice after intravenous injection of Pt-iNOS@ZIF for 7 days. Liver and kidney functions of untreated mice were also evaluated as control. Major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were harvested at 24 h and 7 days for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. H&E staining slides were viewed using a BX41 bright field microscope (Olympus).

Measurement of inflammatory cytokine levels in liver tissues

To evaluate inflammatory cytokine levels,the left liver lobe tissues in each group were harvested at 12 h after surgery to detect the relative mRNA expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12 and IL-6 using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay. Total RNA was extracted from the obtained liver tissues and reverse transcripted into cDNA in a gradient RNA apparatus. Subsequently, fluorescence qPCR amplification was performed and the relative mRNA expression levels of the cytokines mentioned above were measured and calculated. The primer pairs for indicated gentes were described in Supplementary Table 3.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical differences were calculated by Student’s t-test using Excel 2019 software and A One-way analysis of the variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software when appropriate. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and illustrated by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, respectively.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Basic Research Program of Shenzhen (JCYJ20180305163622079), Natural Science Foundation of China (32101074), National University of Singapore Start-up Grant (NUHSRO/2020/133/Startup/08) and NUS School of Medicine Nanomedicine Translational Research Programme (NUHSRO/2021/034/TRP/09/Nanomedicine). All animal experiments were conducted according to the Guide of Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital and the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Shenzhen University (AEWC-SZU).

Author contributions

J.M., L.H.,P.H., Y.Y., and X.C. conceived and designed the project. J.M., L.H., G.L., and J.Z. performed the material synthesis and characterizations. D.Z. and C.J. performed the X.R.D. and elemental mapping studies. J.M., Y.S. performed the cell studies. J.M., C.L., and L.H. performed the animal studies. J.M., C.L., X.W., P.H., and Y.Y. analyzed animal results. J.M., C.L., L.H., P.H., Y.Y., and X.C. analyzed the results and co-wrote the paper. All the authors have discussed the results and approved the final version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Christopher Butch and Horacio Cabral and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The authors declare that the experimental data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information Files. Extra data are available corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jing Mu, Chunxiao Li.

Contributor Information

Liangcan He, Email: liangcanhe@hit.edu.cn.

Peng Huang, Email: peng.huang@szu.edu.cn.

Yuxin Yin, Email: yinyuxin@bjmu.edu.cn.

Xiaoyuan Chen, Email: chen.shawn@nus.edu.sg.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-29772-w.

References

- 1.Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monga SP. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nat. Med. 2018;24:6–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froghi, F., Froghi, S. & Davidson, B. R. Liver sschaemia-reperfusion Injury. In Liver Dis. 129-141 (2020).

- 5.Zhai Y, Petrowsky H, Hong JC, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury in liver transplantation-from bench to bedside. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;10:79–89. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson SM, et al. Multitarget strategies to reduce myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dar WA, Sullivan E, Bynon JS, Eltzschig H, Ju C. Ischaemia reperfusion injury in liver transplantation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Liver Int. 2019;39:788–801. doi: 10.1111/liv.14091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannistrà M, et al. Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury: A systematic review of literature and the role of current drugs and biomarkers. Int. J. Surg. 2016;33:S57–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Li H, Xu X, Saw PE, Zhang L. Nanocarrier-mediated antioxidant delivery for liver diseases. Theranostics. 2020;10:1262–1280. doi: 10.7150/thno.38834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ni D, et al. Ceria nanoparticles meet hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: the perfect imperfection. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1902956. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walayat S, Shoaib H, Asghar M, Kim M, Dhillon S. Role of N-acetylcysteine in non-acetaminophen-related acute liver failure: an updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2021;34:235–240. doi: 10.20524/aog.2021.0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jegatheeswaran S, Siriwardena AK. Experimental and clinical evidence for modification of hepatic ischaemia-reperfusion injury by N-acetylcysteine during major liver surgery. HPB. 2011;13:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thirunavayakalathil MA, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial of N-acetylcysteine infusion following live donor liver transplantation. Hepatol. Int. 2020;14:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J, et al. In situ electrochemical generation of nitric oxide for neuronal modulation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:690–697. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0701-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Midgley AC, Wei Y, Li Z, Kong D, Zhao Q. Nitric-oxide-releasing biomaterial regulation of the stem cell microenvironment in regenerative medicine. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:1805818. doi: 10.1002/adma.201805818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter AW, Schoenfisch MH. Nitric oxide release: Part II. Therapeutic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3742–3752. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15273h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou J, et al. Targeted delivery of nitric oxide via a ‘bump-and-hole’-based enzyme-prodrug pair. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:151–160. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Z, Fu J, Zhang Y. Nitric oxide donor-based cancer therapy: advances and prospects. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:7617–7635. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duranski MR, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2005;115:1232–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu, P. & Li, W. Nitric oxide in liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. in Liver Pathophysiol. 125–127 (2017).

- 21.Bhatraju P, Crawford J, Hall M, Lang JD., Jr Inhaled nitric oxide: Current clinical concepts. Nitric Oxide. 2015;50:114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kröncke K-D, Fehsel K, Kolb-Bachofen V. Nitric oxide: cytotoxicity versus cytoprotection-how, why, when, and where? Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:107–120. doi: 10.1006/niox.1997.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rooks JP. Safety and risks of nitrous oxide labor analgesia: A review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health. 2011;56:557–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira C, et al. NO and HNO donors, nitrones, and nitroxides: Past, present, and future. Med. Res. Rev. 2018;38:1159–1187. doi: 10.1002/med.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao L, et al. Intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:577–583. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Ren J, Qu X. Nanozymes: classification, catalytic mechanisms, activity regulation, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:4357–4412. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, et al. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): next-generation artificial enzymes (II) Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:1004–1076. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00457A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiao L, et al. When nanozymes meet single-atom catalysis. Angew. Chem. 2020;132:2585–2596. doi: 10.1002/ange.201905645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang D, et al. DNA origami nanostructures can exhibit preferential renal uptake and alleviate acute kidney injury. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2:865–877. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan K, et al. In vivo guiding nitrogen-doped carbon nanozyme for tumor catalytic therapy. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02088-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han SI, et al. Epitaxially strained CeO2/Mn3O4 nanocrystals as an enhanced antioxidant for radioprotection. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:2001566. doi: 10.1002/adma.202001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang D, et al. Nanozyme: new horizons for responsive biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:3683–3704. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00718G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, et al. Bioactive ROS-scavenging nanozymes for regenerative medicine: Reestablishing the antioxidant firewall. Nano Sel. 2020;1:285–297. doi: 10.1002/nano.202000021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JY, et al. Bilirubin nanoparticle preconditioning protects against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomaterials. 2017;133:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang B, Chen Y, Shi J. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-based nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:4881–4985. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, et al. Biomimetic design of mitochondria-targeted hybrid nanozymes as superoxide scavengers. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:2006570. doi: 10.1002/adma.202006570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang D-Y, et al. Ultrasmall platinum nanozymes as broad-spectrum antioxidants for theranostic application in acute kidney injury. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;409:127371. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, et al. Nanozyme decorated metal-organic frameworks for enhanced photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:651–661. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katsumi H, et al. Pharmacokinetics and preventive effects of platinum nanoparticles as reactive oxygen species scavengers on hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Metallomics. 2014;6:1050–1056. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00018H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedone D, Moglianetti M, De Luca E, Bardi G, Pompa PP. Platinum nanoparticles in nanobiomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:4951–4975. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00152E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y, et al. Nanozyme-catalyzed cascade reactions for mitochondria-mimicking oxidative phosphorylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:5572–5576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201813771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huo M, Wang L, Chen Y, Shi J. Tumor-selective catalytic nanomedicine by nanocatalyst delivery. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-016-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai X, et al. Nanozyme-involved biomimetic cascade catalysis for biomedical applications. Mater. Today. 2021;44:211–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2020.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, et al. Integrated cascade nanozyme catalyzes in vivo ROS scavenging for anti-inflammatory therapy. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabb2695. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang G, He J, Liu J, Yan X, Fan K. Nanozyme for tumor therapy: Surface modification matters. Exploration. 2021;1:75–89. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen W-H, Vazquez-Gonzalez M, Zoabi A, Abu-Reziq R, Willner I. Biocatalytic cascades driven by enzymes encapsulated in metal-organic framework nanoparticles. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:689. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0117-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Z, et al. Nanocaged enzymes with enhanced catalytic activity and increased stability against protease digestion. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10619. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, C., et al. Enzyme-loaded hemin/G-quadruplex-modified ZIF-90 metal-organic framework nanoparticles: bioreactor nanozymes for the cascaded oxidation of N-hydroxy-ʟ-arginine and sensing applications. Small, 2104420, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Teranishi T, Hosoe M, Tanaka T, Miyake M. Size control of monodispersed Pt nanoparticles and their 2D organization by electrophoretic deposition. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:3818–3827. doi: 10.1021/jp983478m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan Y, Liu Y, Zeng G, Zhao L, Lai Z. Rapid synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanocrystals in an aqueous system. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2071–2073. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05002d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brenner D, Blaser H, Mak TW. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor signalling: live or let die. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:362–374. doi: 10.1038/nri3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roland CR, Walp L, Stack RM, Flye MW. Outcome of Kupffer cell antigen presentation to a cloned murine Th1 lymphocyte depends on the inducibility of nitric oxide synthase by IFN-gamma. J. Immunol. 1994;153:5453–5464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cuzzocrea S, Riley DP, Caputi AP, Salvemini D. Antioxidant therapy: A new pharmacological approach in shock, inflammation, and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:135–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coleman JW. Nitric oxide in immunity and inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1397–1406. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ambalavanan N, John ES, Carlo WA, Bulger A, Philips JB. Feasibility of nitric oxide administration by oxygen hood in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. J. Perinatol. 2002;22:50–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lang JD, et al. Inhaled NO accelerates restoration of liver function in adults following orthotopic liver transplantation. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;117:2583–2591. doi: 10.1172/JCI31892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mu J, He L, Huang P, Chen X. Engineering of nanoscale coordination polymers with biomolecules for advanced applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;399:213039. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen T-T, Yi J-T, Zhao Y-Y, Chu X. Biomineralized metal-organic framework nanoparticles enable intracellular delivery and endo-lysosomal release of native active proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:9912–9920. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the experimental data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information Files. Extra data are available corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.