Abstract

Catalytic asymmetric Tsuji–Trost benzylation is a promising strategy for the preparation of chiral benzylic compounds. However, only a few such transformations with both good yields and enantioselectivities have been achieved since this reaction was first reported in 1992, and its use in current organic synthesis is restricted. In this work, we use N-unprotected amino acid esters as nucleophiles in reactions with benzyl alcohol derivatives. A ternary catalyst comprising a chiral aldehyde, a palladium species, and a Lewis acid is used to promote the reaction. Both mono- and polycyclic benzyl alcohols are excellent benzylation reagents. Various unnatural optically active α-benzyl amino acids are produced in good-to-excellent yields and with good-to-excellent enantioselectivities. This catalytic asymmetric method is used for the formal synthesis of two somatostatin mimetics and the proposed structure of natural product hypoestestatin 1. A mechanism that plausibly explains the stereoselective control is proposed.

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

The catalytic asymmetric benzylations of prochiral nucleophiles are very limited. Here, the authors disclose an asymmetric α−benzylation of N-unprotected amino acids with benzyl alcohol derivatives by a chiral aldehyde-involved catalytic system.

Introduction

The catalytic asymmetric Tsuji–Trost allylation1–9 and benzylation10–12 reactions are important strategies for enantioselectively constructing carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds. Since it was first reported in 197013,14, catalytic asymmetric allylation has been studied extensively and now has widespread applications in organic synthesis15–18. However, few studies of catalytic asymmetric benzylation reactions have been reported19–26. This is probably because Tsuji–Trost allylation proceeds via a stable η3-allyl–palladium intermediate, whereas benzylation takes place via an unstable aromaticity-disrupted η3-benzyl–palladium complex (Fig. 1a)10–12. Catalytic asymmetric benzylation is therefore more challenging. Especially, the successful transformations of the catalytic asymmetric benzylation of prochiral nucleophiles were very limited. In 2010, Trost and Czabaniuk reported the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric benzylation of 3-aryloxindoles to chiral 3,3’-disubstituted oxindoles in excellent yields and with excellent enantioselectivities27. Subsequently, the catalytic asymmetric benzylation of azlactones was reported by the same research group28,29. In 2016, Tabuchi et al. found that the catalytic asymmetric benzylation of active methylene compounds proceeded via a dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation30. In 2018, Snaddon and coworkers used a combined catalytic system derived from a chiral Lewis base and a palladium species for the catalytic asymmetric benzylation of α-aryl- or α-alkenyl-acetic acid esters31. Recently, two highly efficient catalytic asymmetric benzylation reactions of sec-phosphine oxides have been reported by Zhang and Liu32, and Zhang33, respectively (Fig. 1b). The development of new Tsuji–Trost-type benzylation reactions is therefore important because this will provide new methods for the preparation of optically active benzylic compounds and enable new applications of this named reaction in organic synthesis.

Fig. 1. The catalytic asymmetric Tsuji–Trost-type reactions.

a The comparison of the allylation and benzylation reactions. b The reported prochiral nucleophiles involved in the catalytic asymmetric benzylation reactions. c The direct catalytic asymmetric α−benzylation of N-unprotected amino acid esters by a chiral aldehyde-involved catalytic system (this work).

The direct catalytic asymmetric α−benzylation of N-unprotected amino acids is one of the simplest methods for preparing optically active unnatural α−benzyl amino acids. However, the strong nucleophilicity of the amino group and the weak α−carbon acidity of the N-unprotected amino acid make this direct benzylation challenging. Until now, this type of prochiral nucleophile has not been used in Tsuji–Trost benzylation reactions (Fig. 1b)34,35. The chiral aldehyde catalysis based on imine activation disclosed by our group provides a promising strategy for achieving this challenging reaction because the chiral aldehyde catalyst can simultaneously mask the amino group and enhance the α−carbon acidity via in situ formation of an imine with a N-unprotected amino acid ester group36–43.

Here, we report a direct catalytic asymmetric Tsuji–Trost benzylation of N-unprotected amino acids. Use of a ternary catalytic system comprising a chiral aldehyde, a palladium species, and a Lewis acid enables the formation of the corresponding optically active α−benzyl amino acids in good-to-excellent yields and with good-to-excellent enantioselectivities (Fig. 1c). The use of this reaction for the synthesis of structurally diverse unnatural amino acids, somatostatin mimetics, and the natural product hypoestestatin 1, and identification of a possible reaction mechanism, are explored.

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

Our work began with the evaluation of the benzylation of ethyl alaninate (1a) with tert-butyl (naphthalen-2-ylmethyl) carbonate (2a) by using a combined catalytic system44–46 consisting of chiral aldehyde 3h (10 mol%), a palladium complex (5 mol%), and zinc chloride (40 mol%) in toluene, with the assistance of 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)propane (dppp, 10 mol%) as a ligand and the base 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (TMG, 100 mol%). This reaction proceeded smoothly at 60 °C in an inert atmosphere to give the desired product 5a in 51% yield and with 76% enantioselective excess (ee) (Table 1, entry 1). These conditions were adopted as the standard conditions and optimization of these conditions was investigated systematically. First, various chiral aldehydes were used as catalysts instead of 3h (Table 1, entry 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Among catalysts 3 and 4, chiral aldehyde 3m showed the highest catalytic activation ability in this reaction, and product 5a was obtained in the highest yield (85%) in 4hs. However, the enantioselectivity was lower than that achieved with 3h (62% ee vs 76% ee). Chiral aldehyde 4c gave 5a with the highest enantioselectivity (78% ee), but the yield was low (6%). Next, we tested various palladium sources in this reaction. We found that this reaction is sensitive to the palladium source; [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 gave the best results (Table 1, entry 3 and Supplementary Table 2). The ligands, Lewis acids, and bases were then sequentially screened, but no better results were obtained (Table 1, entries 4–6; Supplementary Tables 3–5). Screening of the alkoxy groups of amino esters 1 and leaving groups of benzyl alcohols 2 did not lead to further improvements in the yield and enantioselectivity of 5a (Table 1, entries 7 and 8; Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Various solvents were then screened; the use of mesitylene improved the yield to 94%, but the enantioselectivity decreased slightly (Table 1, entry 9 and Supplementary Table 8). Mesitylene was used as the solvent in the further screening of the bases and chiral aldehyde catalysts. We found that the combination of super organic base tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane (TDMAIP) (1.4 equivalents) and chiral aldehyde catalyst 3f could give 5a in 94% yield and with 84% ee (Table 1, entry 10). The enantioselectivity of 5a was further enhanced by doubling the reactant concentrations (Table 1, entry 11). On the basis of these results, the reaction conditions in Table 1, entry 12 were identified as the optimal conditions and were used in subsequent investigations.

Table 1.

Reaction condition optimization of naphthylmethanol involved benzylationa.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation from standard reaction conditions | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1 | No | 51 | 76 |

| 2 | 3h was replaced by other chiral aldehydes 3 or 4 | 4–85 | 20–78 |

| 3 | [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 was replaced by other transition metals | 0-trace | ND |

| 4 | dppp was replaced by other ligands | 0–35 | 48–75 |

| 5 | ZnCl2 was replaced by other Lewis acids | 0–46 | 6–74 |

| 6 | TMG was replaced by other bases | 0–46 | 15–55 |

| 7 | Et of 1a was replaced by Me, Bn or nPr | 40–60 | 69–76 |

| 8 | OBoc of 2a was replaced by other Leaving Groups | 4–47 | 32–72 |

| 9 | PhCH3 was replaced by mesitylene | 95 | 74 |

| 10 | mesitylene as solvent, TDMAIP as base, and 3f as catalyst | 94 | 84 |

| 11 | entry 10 and 0.5 mL mesitylene as solvent | 93 | 90 |

ND not determined.

aReaction conditions: 1 (0.30 mmol), 2 (0.20 mmol), 3 (0.02 mmol), dppp (0.02 mmol), [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (0.01 mmol), TMG (0.20 mmol), and ZnCl2 (0.08 mmol) were stirred in toluene (1.0 mL) at 60 °C for indicated time.

bIsolated yield.

cThe enantioselective excess was determined by chiral HPLC.

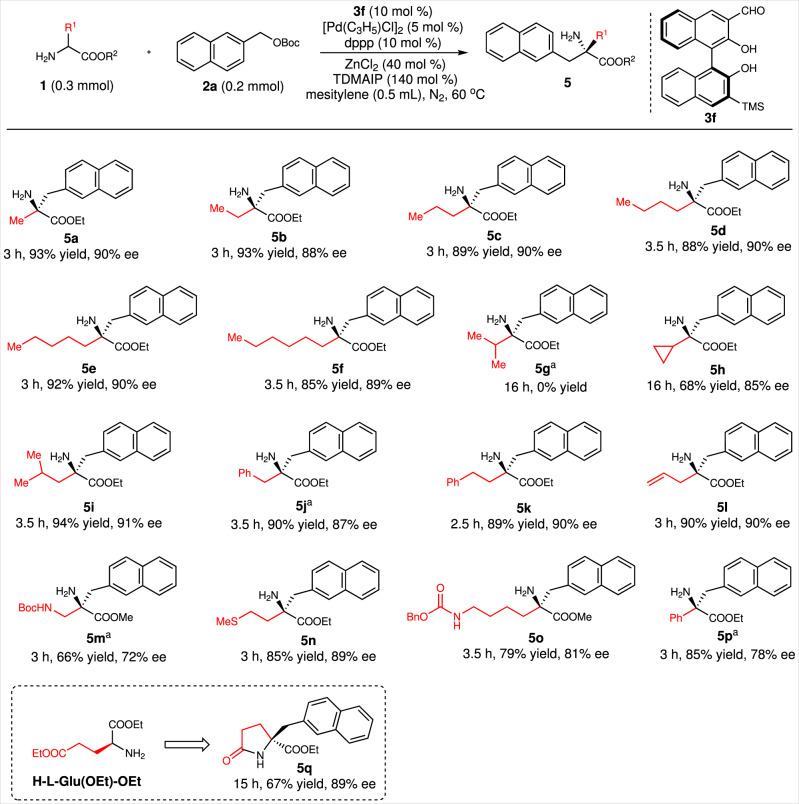

Substrate scope with amino acids

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, we then investigated the amino acid and arylmethanol substrate scopes. First, various amino acids bearing linear α−alkyl groups were introduced as reactants. The results indicated that amino acids containing linear alkyls with one–six carbon atoms all reacted efficiently with 2a to give products 5a–5f in excellent yields and with excellent enantioselectivities. The reactivities of amino acids with α-branched alkyls are greatly affected by the steric effects. For example, the ethyl valinate could not participate in this reaction under the optimal reaction conditions (Fig. 2, 5g), whereas the ethyl 2-amino-2-cyclopropylacetate and ethyl leucinate gave corresponding products in good yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 2, 5h–5i). The use in this reaction of amino acid esters bearing phenyl, C=C, amino, or sulfur ether groups on their side chains was then examined. All these amino acid esters reacted efficiently with 2a to give 5j–5o in good-to-excellent yields and enantioselectivities. α-phenyl glycine ethyl ester was also a good reaction partner for 2a, giving product 5p in 86% yield and 78% ee. When diethyl glutamate was used as the donor in the reaction with 2a, a tandem benzylation–lactamization proceeded smoothly to give γ-lactam 5q in 67% yield and with 89% ee. This type of chiral γ-lactams was extensively used as building blocks in the asymmetric synthesis of natural products47–50.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of amino acids.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.30 mmol), 2a (0.20 mmol), 3f (0.02 mmol), dppp (0.02 mmol), [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (0.01 mmol), tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane (TDMAIP, 0.20 mmol), and ZnCl2 (0.08 mmol) were stirred in mesitylene (0.5 mL) at 60 °C under the nitrogen atmosphere for indicated time. Isolated yields. The enantioselective excess (ee) was determined by HPLC. aAt 80 °C.

Substrate scope with polycyclic arymethyl alcohol derivatives

The polycyclic arylmethyl alcohol substrate scope was investigated. 2-Naphthylmethanol derivatives bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups were good reaction partners for amino acid ester 1a, and gave products 6a–6c in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. 1-Naphthylmethanol derivatives also reacted with 1a efficiently, but the required reaction temperature was higher than that for the reactions of 2-naphthylmethanols and 1a (Fig. 3, 6d–6h). This may be because of the steric effect of the 1-naphthyl group. A series of nitrogen-containing arylmethanol derivatives were then tested. All these compounds reacted efficiently with 1a to give the corresponding products 6i–6n in excellent experimental outcomes. Tricyclic arylmethanol derivatives, such as anthracen-2-ylmethanol and phenanthren-9-ylmethanol derived tert-butyl carbonates gave products 6o–6q in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Adapalene is a drug that is used in the treatment of skin diseases. Modification of this drug molecule was achieved by the catalytic asymmetric α-benzylation of amino acid ester 1a with the adapalene-derived tert-butyl carbonate; 6r was obtained in 95% yield and with 88% ee. We found the monocyclic tert-butyl benzyl carbonate could not react with 1a under the optimal reaction conditions.

Fig. 3. Substrate scope of polycyclic benzyl alcohol derivatives.

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.30 mmol), 2 (0.20 mmol), 3f (0.02 mmol), dppp (0.02 mmol), [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (0.01 mmol), tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane (TDMAIP, 0.20 mmol), and ZnCl2 (0.08 mmol) were stired in mesitylene (0.5 mL) at 60 °C under the nitrogen atmosphere for indicated time. Isolated yields. The enantioselective excess (ee) was determined by HPLC. aAt 80 °C. bYields and ees were given by the N-Boc-protected derivatives.

Optimization of the monocyclic benzyl alcohol involved benzylation reaction

To further expand the substrate scope, the reaction conditions of the asymmetric benzylation reaction with monocyclic benzyl alcohol were investigated (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 14). Inspired by Trost’s work29,30, we chose benzyl diethyl phosphate 2b as a benzylation reagent. As expected, this reaction proceeded smoothly giving desired product 7a in 26% yield and 75% ee (Table 2, entry 1). The introduction of chiral ligand L1 improved the yield of 7a greatly (Table 2, entry 2). Then, the matching relationship between chiral aldehyde and ligand was investigated. Results indicated that the combination of chiral aldehyde 3f and ligand (R)-L1 was suitable for this reaction (Table 2, entry 3 vs entry 4). After we replaced the reactant 1a with 1b, product 7b was generated in 83% yield and 95% ee (Table 2, entry 5). For the reaction of 1b and 2b, the usage of a single chiral catalyst, either with the chiral aldehyde 3f or with the chiral ligand (R)-L1, could not give satisfactory experimental outcomes (Table 2, entries 6–7). According to these results, the optimal reaction conditions for the catalytic asymmetric α−benzylation of N-unprotected amino acids with monocyclic benzyl alcohols were determined.

Table 2.

Reaction optimization of monocyclic benzyl alcohol involved benzylation reactiona.

| Entry | Ar*CHO | R | Ligand | Time (h) | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3f | Et | dppp | 12 | 26 | 75 |

| 2d | 3f | Et | (R)-L1 | 9 | 60 | 78 |

| 3d | 3a | Et | (S)-L1 | 12 | 51 | 19 |

| 4d | 3a | Et | (R)-L1 | 12 | 60 | 72 |

| 5 | 3f | tBu | (R)-L1 | 9.5 | 83 | 95 |

| 6d | 3f | tBu | dppp | 9.5 | 50 | 83 |

| 7 | rac-3a | tBu | (R)-L1 | 9.5 | 62 | 74 |

aReaction conditions: 1 (0.30 mmol), 2a (0.20 mmol), 3 (0.02 mmol), L1 (0.02 mmol), [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (0.01 mmol), TDMAIP (0.28 mmol), and ZnCl2 (0.08 mmol) were stirred in mesitylene (0.5 mL) at 60 °C for indicated time.

bIsolated yield.

cThe enantioselective excess was determined by chiral HPLC.

dWith 10 mol% palladium and 20 mol% (R)-L1.

Substrate scopes with monocyclic benzyl alcohol derivatives and amino acid esters

With these optimal reaction conditions listed in Table 2, entry 5, corresponding substrate scopes were investigated. Results indicated that various monocyclic benzyl phosphates bearing an ortho-, meta- or para-substituent were good acceptors for this reaction (Fig. 4, 7c–7k). Benzyl phosphates having two substituents on the phenyl ring also participated in this reaction well (Fig. 4, 7l–7m). Thiophen-3-ylmethanol-derived phosphate could give product 7n in 80% yield and 96% ee. Then, five amino acids derived tert-butyl esters were tested. All of them gave corresponding products in high yields and excellent enantioselectivities (Fig. 4, 7o–7s). Thus, both of poly- and monocyclic benzyl alcohol derivatives were successfully introduced as benzylation regents.

Fig. 4. Substrate scope of monocyclic benzyl alcohol derivatives and amino acid esters.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.30 mmol), 2 (0.20 mmol), 3f (0.02 mmol), (R)-L1 (0.02 mmol), [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (0.01 mmol), tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane (TDMAIP, 0.28 mmol), and ZnCl2 (0.08 mmol) were stired in mesitylene (0.5 mL) at 60 °C under the nitrogen atmosphere for indicated time. Isolated yields. The enantioselective excess (ee) was determined by HPLC. aEe values were given by the N-Cbz-protected derivatives. bWith 10 mol% palladium, 20 mol% (R)-L1, and at 80 °C.

Formal synthesis of SRIF mimetics

Compounds 11a and 11b are somatotropin release inhibiting factor (SRIF) mimetics with IC50 values of 2.44 and 1.27 μM, respectively, for the somatostatin receptor hsst 551. Chiral amino acid ester 10, which bears an aldehyde group, is one of the key chiral building blocks for the synthesis of these two SRIF mimetics. Ten steps are involved in the reported preparation of 10 from the corresponding amino acids. We envisioned that this chiral synthon could be obtained from amino acid ester 8 by sequential protection and oxidative cleavage. We chose amino acid ester 1b as the donor in reactions with naphthalenemethanol derivatives 2a and 2b under the optimal reaction conditions. As expected, products 8a and 8b were generated in good yields and with good enantioselectivities. After protection of the amino group in 7 with Cbz, oxidative cleavage of C=C bonds was performed. The chiral amino acid esters 9a and 9b were obtained in three steps and can be used for the formal synthesis of SRIF mimetics 10a and 10b (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. Synthetic applications.

a The retrosynthetic analysis and formal synthesis of somatotropin release inhibiting factor (SRIF) mimetics. b The retrosynthetic analysis and formal synthesis of (S)-hypoestestatin 1. TDMAIP tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane.

Formal synthesis of hypoestestatin 1

13a-Methylphenanthroindolizidine alkaloids are important members of the phenanthroindolizidine alkaloid family52–56. These alkaloids show a wide range of biological activities. Among them, four compounds, one of which is hypoestestatin 1, have the same core phenanthroindolizidine skeleton; their structures differ in terms of the substituents on the phenanthrene ring. Wang’s work indicated that hypoestestatin 1 can be prepared from the chiral α-phenanthryl amino acid ester 1357,58. We envisioned that this chiral synthon could be obtained from γ-lactam 12 by selective reduction. The result obtained for products 5q show that 12 can be generated by the asymmetric benzylation reaction of dimethyl glutamate and a carbonate derived from a substituted phenanthrylmethanol. On the basis of this retrosynthetic analysis, we began to explore new synthetic routes to the proposed molecule structure of hypoestestatin 1. Under the optimal reaction conditions, 1c and 2c reacted smoothly to give γ-lactam 12 in 65% yield and with 86% ee. Selective reduction of the amide group of 12 gave the desired chiral synthon 13 in 62% yield and with 85% ee. According to a reported procedure, hypoestestatin 1 can be synthesized from 13 in four steps (Fig. 5b)57. The target natural product could therefore be obtained via six steps in total. This strategy could be potentially used to synthesize other three natural products, as shown in Fig. 5b.

Discussion

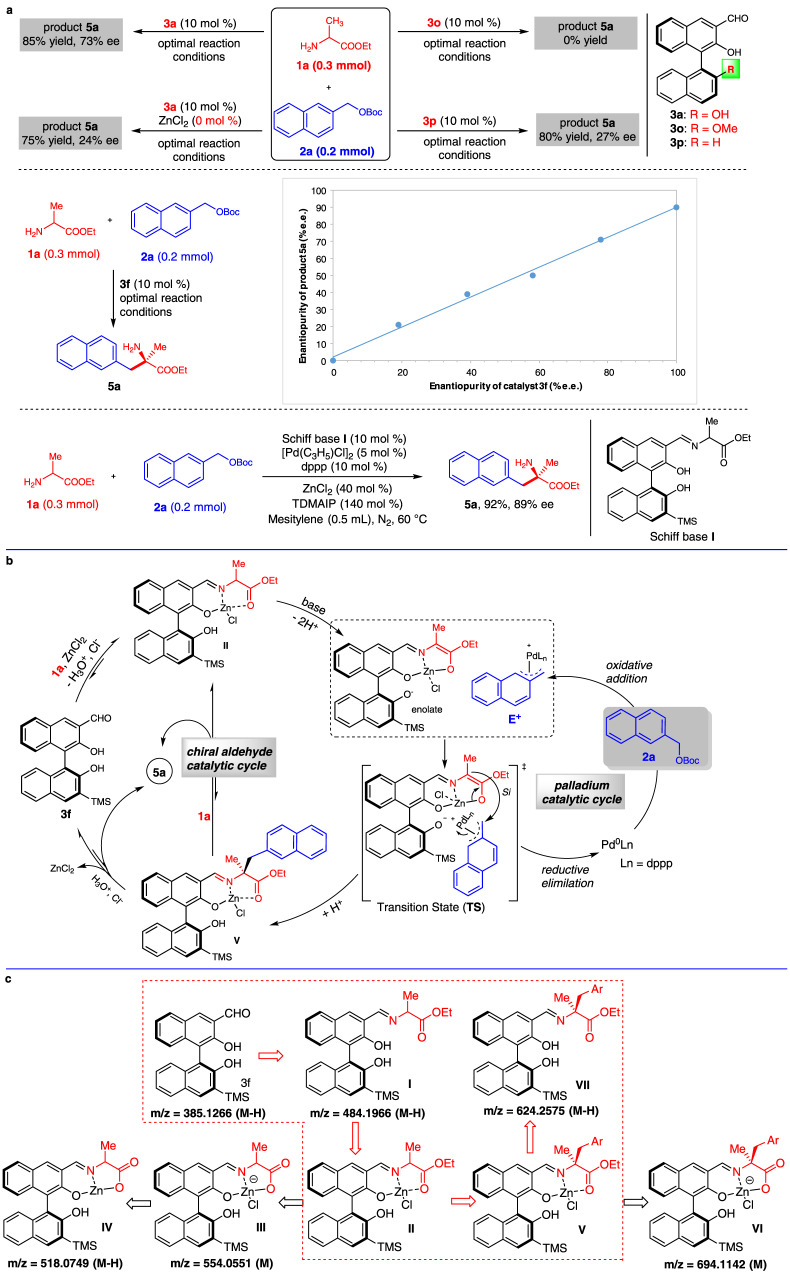

The possible reaction mechanism was then investigated. Generally, the chiral aldehyde catalyst generates an active enolate via sequential Schiff base formation and deprotonation, and the palladium catalyst generates an active electrophile by oxidative addition. The key issue is the identification of the transition state involved in this reaction. This was clarified by performing various control experiments (Fig. 6a). Under the optimal reaction conditions, chiral aldehyde 3a gave product 5a in 85% yield and with 73% ee. In the absence of the Lewis acid ZnCl2, both the yield and enantioselectivity of 5a decreased. This indicates the possible formation of a Zn2+–Schiff base complex during the reaction. Two modified chiral aldehydes were then used as catalysts. We found that chiral aldehyde 3o did not promote this reaction efficiently. Chiral aldehyde 3p gave product 5a in 80% yield, but the ee was only 27%. The results of these two control experiments indicate that the 2’-hydroxyl group in chiral aldehydes 3 is crucial for this reaction. We envisioned that the 2’- hydroxyl group in the chiral aldehyde catalyst acts as a site for coordination with an active η3-benzyl–palladium complex (E+). The linear relationship between the ee values of 3f and those of the product 5a indicated that one molecule of chiral aldehyde catalyst participated in the stereoselective control model. In addition, we found the Schiff base I was an efficient catalyst and produced 5a in 90% yield and 89% ee, which indicated a possible amine exchange process existed in the catalytic cycle. Based on these results, a transition state TS and possible catalytic cycles were proposed (Fig. 6b). In this transition state, the Si face of the enolate undergoes an intramolecular electrophilic attack to give Schiff base V enantioselectively. Finally, the chiral aldehyde catalytic cycle is completed by hydrolysis or amine exchange and the palladium catalytic cycle is completed by reductive elimination (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Reaction mechanism investigations.

a Control experiments and nonlinear effect investigation. b Proposed catalytic cycles. c Key intermediated detected by HRMS. TDMAIP tris(dimethylamino)iminophosphorane.

The key intermediates involved in this proposed reaction mechanism were then verified by HRMS with negative ion mode (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs. 2–6). The Schiff bases I (m/z = 484.1966, M–H) and VII (m/z = 624.2575, M–H) could be observed directly in the reaction system. Although we could not find the key intermediates II and V directly, three fragments derived from them were observed and confirmed by comparing their isotopic distribution with theoretical data. With the dissociation of ethyl, ionic fragments III (m/z = 554.0551, M) and VI (m/z = 694.1142, M) were generated from intermediates II and V, respectively. It was because the intermediates II and V were not stable enough for HRMS detection; with the activation of Lewis acid ZnCl2, the C–O bond of the ethoxy was readily dissociated by the electron impact of ESI source. As result, stable ionic fragments III and VI were generated. A neutral intermediate IV (m/z = 518.0749, M–H), which was most likely generated from fragment III with the dissociation of a Cl−, was also detected by HRMS. All of the isotopic distributions of III, IV, and VI were following the theoretical data (Supplementary Figs. 3–5). The existence of fragments III, IV, and VI confirmed the formation of Schiff base—Zn complexes II and V in this reaction.

In this work, we have developed a highly efficient asymmetric α-benzylation reaction of N-unprotected amino acids and arylmethanols. The reaction is promoted by a combination of catalytic systems, namely a chiral aldehyde, a palladium species, and a Lewis acid. Various chiral α-benzyl amino acids are produced in high-to-excellent yields and with high-to-excellent enantioselectivities. This strategy can be conveniently used in the preparation of SRIF mimetics and the formal synthesis of the natural product (S)-hypoestestatin 1. Based on the results of control experiments and nonlinear effect investigation, a reasonable reaction mechanism is proposed. The key intermediates involved in the chiral aldehyde catalytic cycle are confirmed by HRMS detection.

Methods

General procedure for the catalytic asymmetric α−benzylation of amino acids

To a 10 mL vial charged with [Pd(C3H5)Cl]2 (3.6 mg, 0.01 mmol) and ligand (dppp or R-L1) (0.02 mmol) was added 0.5 mL mesitylene, and the mixture was stirred under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature for 30 min. Then, ethyl amino acid ester 1 (0.3 mmol), benzyl alcohol derivative 2 (0.2 mmol), chiral aldehyde 3f (7.7 mg, 0.02 mmol), ZnCl2 (10.9 mg, 0.08 mmol) and TDMAIP (50.9 µL, 0.28 mmol) were added. The mixture was continuously stirred at indicated reaction temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere. After the reaction completed, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography column on silica gel (eluent: petroleum ether/ethyl acetate/triethylamine = 200/100/3). The details of the full experiments and compound characterizations are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from NSFC (22071199, 21871223) and the Chongqing Science Technology Commission (cstccxljrc201701, cstc2018jcyjAX0548).

Author contributions

W.W. and G.Q.X. conceived this project. L.J.H., L.J., S.Q.W., and L.Y. carried out the experiments. W.Z.L. and C.T. performed the HRMS analysis. G.Q.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wei Wen, Email: wenwei1989@swu.edu.cn.

Qi-Xiang Guo, Email: qxguo@swu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-30277-9.

References

- 1.Tsuji J. Dawn of organopalladium chemistry in the early 1960s and a retrospective overview of the research on palladium-catalyzed reactions. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:6330–6348. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trost BM. Metal catalyzed allylic alkylation: its development in the Trost laboratories. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:5708–5733. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver JD, Recio A, III, Grenning AJ, Tunge JA. Transition metal-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation and benzylation reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1846–1913. doi: 10.1021/cr1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trost BM, Machacek MR, Aponick AP. Predicting the stereochemistry of diphenylphosphino benzoic acid (DPPBA)-based palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation reactions: a working model. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:747–760. doi: 10.1021/ar040063c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost BM, VanVranken DL. Asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395–422. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu G, Wu J-R, Huang Y, Yang Y-W. Enantioselective synthesis of quaternary carbon stereocenters by asymmetric allylic alkylation: a review. Chem. Asian J. 2021;16:1864–1877. doi: 10.1002/asia.202100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian F, Zhang J, Yang W, Deng W. Progress in iridium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions via synergetic catalysis. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2020;40:3262–3278. doi: 10.6023/cjoc202005008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Yu J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhou Q. Efficient activation of allylic alcohols in Pd-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2020;40:2669–2677. doi: 10.6023/cjoc202005013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noreen S, et al. Novel chiral ligands for palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation/asymmetric Tsuji-Trost reaction: a review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2019;23:1168–1213. doi: 10.2174/1385272823666190624145039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bras J, Muzart J. Production of Csp(3)-Csp(3) bonds through palladium-catalyzed Tsuji-Trost-Type reactions of (hetero)benzylic substrates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016;15:2565–2593. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201600094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trost BM, Czabaniuk LC. Structure and reactivity of late transition metal η3‐Benzyl complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:2826–2851. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwano R. Catalytic transformations of benzylic carboxylates and carbonates. Synth.-Stuttg. 2009;7:1049–1061. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji J, Takahashi H, Morikawa M. Organic syntheses by means of noble metal compounds XVII. Reaction of π-allylpalladium chloride with nucleophiles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965;49:4387. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)71674-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trost BM, Fullerton TJ. New synthetic reactions. allylic alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:292–294. doi: 10.1021/ja00782a080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammadkhani L, Heravi MM. Applications of transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution in total synthesis of natural products: an update. Chem. Rec. 2021;21:29–68. doi: 10.1002/tcr.202000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, Y., Oble, J., Pradal, A. & Poli, G. Catalytic domino annulations through η3-allylpalladium chemistry: a never-ending story. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 942–961 (2020).

- 17.Trost BM, Kalnmals CA. Annulative allylic alkylation reactions between dual electrophiles and dual nucleophiles: applications in complex molecule synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2020;26:1906–1921. doi: 10.1002/chem.201903961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trost BM, Crawley ML. Asymmetric transition-metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations: applications in total synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2921–2944. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legros J-Y, Toffano M, Fiaud J-C. Asymmetric palladium-catalyzed nucleophilic substitution of racemic 1-naphthylethyl esters. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry. 1995;6:1899–1902. doi: 10.1016/0957-4166(95)00247-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legros J-Y, Boutros A, Fiaud J-C, Toffano M. Asymmetric palladium-catalyzed nucleophilic substitution of 1-(2-naphthyl)ethyl acetate by dimethyl malonate anion. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2003;196:21–25. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00631-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assié M, Legros J-Y, Fiaud J-C. Asymmetric palladium-catalyzed benzylic nucleophilic substitution: high enantioselectivity with the DUPHOS family ligands. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry. 2005;16:1183–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2005.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assié M, Meddour A, Fiaud J-C, Legros J-Y. Enantiodivergence in alkylation of 1-(6-methoxynaphth-2-yl)ethyl acetate by potassium dimethyl malonate catalyzed by chiral palladium-DUPHOS complex. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry. 2010;21:1701–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Najib A, Hirano K, Miura M. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric benzylic substitution of secondary benzyl carbonates with nitrogen and oxygen nucleophiles. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2438–2441. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsude A, Hirano K, Miura M. Palladium-catalyzed benzylic phosphorylation of diarylmethyl carbonates. Org. Lett. 2018;20:3553–3556. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najib A, Hirano K, Miura M. Asymmetric synthesis of diarylmethyl sulfones by palladium-catalyzed enantioselective benzylic substitution: a remarkable effect of water. Chem. Eur. J. 2018;24:6525–6529. doi: 10.1002/chem.201800744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen X, Qian L, Yu S. Photoredox/palladium-cocatalyzed enantioselective alkylation of secondary benzyl carbonates with 4-alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines. Sci. China Chem. 2020;63:687–691. doi: 10.1007/s11426-019-9732-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trost BM, Czabaniuk LC. Palladium-Catalyzed asymmetric benzylation of 3-aryl oxindoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15534–15536. doi: 10.1021/ja1079755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trost BM, Czabaniuk LC. Benzylic phosphates as electrophiles in the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric benzylation of azlactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5778–5781. doi: 10.1021/ja301461p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trost BM, Czabaniuk LC. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric benzylation of azlactones. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:15210–15218. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabuchi S, Hirano K, Miura M. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric benzylic alkylation of active methylene compounds with α−naphthylbenzyl carbonates and pivalates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:6973–6977. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz KJ, Yang C, Fyfe JWB, Snaddon TN. Enantioselective α-benzylation of acyclic esters using π−extended electrophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:12102–12105. doi: 10.1002/anie.201806742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai Q, Liu L, Zhang JL. Palladium/Xiao-phos-catalyzed kinetic resolution of sec-phosphineoxides by P-benzylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:27247–27252. doi: 10.1002/anie.202111957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai WQ, Wei Q, Zhang QW. Ni-catalyzed enantioselective benzylation of secondary phosphine oxide. Org. Lett. 2022;24:1258–1262. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng, Y. et al. Nickel/copper-cocatalyzed asymmetric benzylation of aldimine esters for the enantioselective synthesis of α-quaternary amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 10.1002/anie.202203448 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Chang X, Ran J-D, Liu X-T, Wang C-J. Catalytic asymmetric benzylation of azomethine ylides enabled by synergistic lewis acid/palladium catalysis. Org. Lett. 2022;24:2573–2578. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Gu Q, You S-L. Enantioselective carbonyl catalysis enabled by chiral aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:6818–6825. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JF, Liu YE, Gong X, Shi LM, Zhao BG. Biomimetic chiral pyridoxal and pyridoxamine catalysts. Chin. J. Chem. 2019;37:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu B, et al. Catalytic asymmetric direct α-alkylation of amino esters by aldehydes via imine activation. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:1988–1991. doi: 10.1039/c3sc53314j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, et al. Carbonyl catalysis enables a biomimetic asymmetric Mannich reaction. Science. 2018;360:1438–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen W, et al. Chiral aldehyde catalysis for the catalytic asymmetric activation of glycine esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:9774–9780. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b06676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen W, et al. Diastereodivergent chiral aldehyde catalysis for asymmetric 1,6-conjugated addition and Mannich reactions. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L, Luo M-J, Zhu F, Wen W, Guo Q-X. Combining chiral aldehyde catalysis and transition-metal catalysis for enantioselective α−allylic alkylation of amino acid esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:5159–5164. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu F, et al. Direct catalytic asymmetric α‑allylic alkylation of aza-aryl methylamines by chiral-aldehyde-involved ternary catalysis system. Org. Lett. 2021;23:1463–1467. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen DF, Han ZY, Zhou XL, Gong LZ. Asymmetric organocatalysis combined with metal catalysis: concept, proof of concept, and beyond. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2365–2377. doi: 10.1021/ar500101a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han ZY, Gong LZ. Asymmetric organo/palladium combined catalysis. Prog. Chem. 2018;30:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang PS, Chen DF, Gong LZ. Recent progress in asymmetric relay catalysis of metal complex with chiral phosphoric acid. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020;378:9. doi: 10.1007/s41061-019-0263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stathakis, C. I., Yioti, E. G. & Gallos, J. K. Total syntheses of (-)-α-kainic acid. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 4661–4673 (2012).

- 48.Clayden J, Read B, Hebditch KR. Chemistry of domoic acid, isodomoic acids, and their analogues. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:5713–5724. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2005.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panday SK, Prasad J, Dikshit DK. Pyroglutamic acid: a unique chiral synthon. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry. 2009;20:1581–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Najera C, Yus M. Pyroglutamic acid: a versatile building block in asymmetric synthesis. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry. 1999;10:2245–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(99)00213-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith AB, III, et al. Design, Synthesis, and binding affinities of pyrrolinone-based somatostatin mimetics. Org. Lett. 2005;7:399–402. doi: 10.1021/ol0476974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan CC, Dong JY, Liu YX, Li YQ, Wang QM. Target-directed design, synthesis, antiviral activity, and SARs of 9-substituted phenanthroindolizidine alkaloid derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69:7565–7571. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c02276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia XH, Zhao HX, Du CL, Tang WZ, Wang XJ. Possible pharmaceutical applications can be developed from naturally occurring phenanthroindolizidine and phenanthroquinolizidine alkaloids. Phytochemistry Rev. 2021;20:845–868. doi: 10.1007/s11101-020-09723-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jo YI, Burke MD, Cheon CH. Modular syntheses of phenanthroindolizidine natural products. Org. Lett. 2019;21:4201–4204. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu GQ, Reimann M, Opatz T. Total synthesis of phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids by combining iodoaminocyclization with free radical cyclization. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:6124–6148. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimada K, et al. An efficient synthesis of phenanthroindolizidine core via hetero Diels-Alder reaction of in situ generated alpha-allenylchalcogenoketenes with cyclic imines. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019;14:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Su B, Cai CL, Wang QM. Enantioselective approach to 13a-methylphenanthroindolizidine alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:7981–7987. doi: 10.1021/jo3012122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Su B, Cai CL, Deng M, Wang QM. Spatial configuration and three-dimensional conformation directed design, synthesis, antiviral activity, and structure−activity relationships of phenanthroindolizidine analogues. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:2039–2045. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b06112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.