Abstract

The hypothalamus is a central regulator of body weight and energy homeostasis. There is increasing evidence that innate immune activation in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) is a key element in the pathogenesis of diet-induced obesity. Microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain parenchyma, have been shown to play roles in diverse aspects of brain function, including circuit refinement and synaptic pruning. As such, microglia have also been implicated in the development and progression of neurological diseases. Microglia express receptors for and are responsive to a wide variety of nutritional, hormonal, and immunological signals that modulate their distinct functions across different brain regions. We showed that microglia within the MBH sense and respond to a high-fat diet and regulate the function of hypothalamic neurons to promote food intake and obesity. Neurons, glia, and immune cells within the MBH are positioned to sense and respond to circulating signals that regulate their capacity to coordinate aspects of systemic energy metabolism. Here, we review the current knowledge of how these peripheral signals modulate the innate immune response in the MBH and enable microglia to regulate metabolic control.

Subject terms: Microglial cells, Obesity, Metabolic syndrome, Hypothalamus, Neuroimmunology

Obesity: The role of immune cells in the brain

Immune cells in the brain that contribute to metabolic dysfunction could offer a therapeutic target for treating obesity. In a review article, a team led by Martin Valdearcos and Suneil Koliwad from the University of California, San Francisco, USA, discuss the evidence linking microglia and other immune cells found in the brain’s hypothalamus region to the regulation of food intake and weight gain. The researchers describe how hormones, inflammatory molecules, nutrients, and microbiome-derived factors can all impact microglia in ways that affect how the immune cells interact with the neurons responsible for metabolic control. Although much remains to be learned about which aspects of microglial function are integral to obesity promotion, the authors argue that, in principle, drugs that target these immune cells could help combat excess weight gain and related metabolic disorders.

Introduction

In many animal species, the central nervous system (CNS) plays a key role in sensing and controlling energy status. In this context, in mammals, the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) in particular has emerged as a master regulator of energy homeostasis. The MBH contains the median eminence (ME) and arcuate nucleus (ARC) and is particularly positioned to sense circulating factors that regulate metabolism. The ME and the ventromedial ARC are circumventricular organs (CVOs) that lack a true blood–brain barrier (BBB) formed by endothelial cells, resulting in exposure to circulating factors from the hypophyseal portal system1,2. The remaining portion of the ARC may be exposed to circulating factors via diffusion, and the ARC is also open to signals from the CSF via the infundibular recess1. Thus, the MBH is a critical brain region that integrates circulating signals from the periphery to regulate systemic metabolism.

Recent research has revealed that the regulation of hypothalamic function involves complex interactions between neurons and immune cells within the MBH3. Both the immune and nervous systems have evolved to sense intrinsic and extrinsic signals to coordinate a multicellular response that contributes to the maintenance of tissue homeostasis. Neuroimmune interactions are bidirectional, and immune cells produce signals such as cytokines, neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, and hormones to modulate neuronal functions4,5.

Microglia are specialized resident myeloid cells in the CNS, and there is growing evidence highlighting an expanding array of functions of these cells beyond their established roles in immunosurveillance and the clearance of cellular debris. For instance, microglia play a crucial role in shaping and maintaining neuronal circuits, which is a process called synaptic pruning, in which damaged or unnecessary synapses are eliminated to maintain synaptic homeostasis6,7. Furthermore, microglia also produce various neurotrophic factors to properly regulate neuronal excitability and promote the differentiation and survival of neurons8,9. Therefore, microglia are central players that contribute to neuroimmune interactions to maintain brain homeostasis.

With respect to the hypothalamus, we showed that microglia in the MBH can sense increased consumption of saturated fats and transduce this signal to instruct local neurons engaged in controlling hunger and satiety10. Moreover, microglial activation alone is sufficient to stimulate food intake and body weight gain in adult mice11. Hypothalamic inflammatory pathways are rapidly activated in response to the initiation of high-fat diet (HFD) feeding, far before any significant weight gain manifests, suggesting that this response is causative in the pathogenesis of obesity. As such, a better understanding of the dietary, metabolic, and immunological factors that drive microglial activation in the MBH will be critical in potentially developing new therapeutic strategies for obesity and related metabolic disorders.

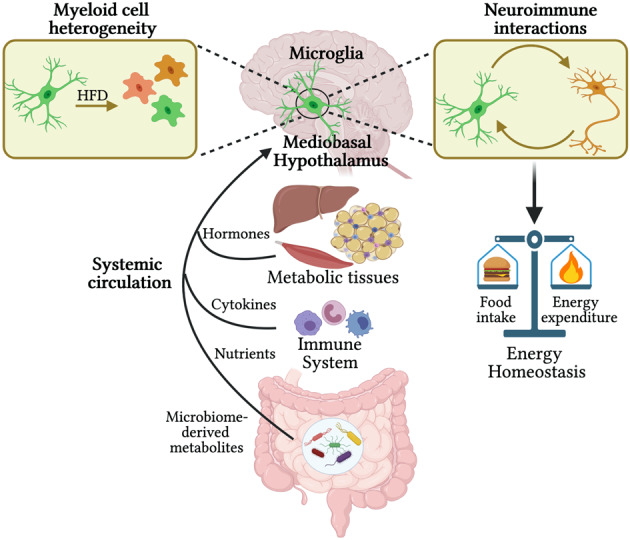

The signaling mechanisms connecting consumption of a HFD to the innate immune response in the MBH remain largely unknown, but ongoing work to elucidate connections between systemic signals and the MBH provides clues as to how such signals may be relayed (Fig. 1). One possible mechanism is circulating nutritional or hormonal signaling molecules that are either directly obtained from the diet or generated in the periphery in response to a HFD and received by the MBH. For example, the enteric immune system can also release cytokines directly into the circulation, and these cytokines can reach the brain and modulate the neuronal activity of CVOs, including the MBH12. In addition, circulating immune cells have been shown to respond to a HFD and can themselves be recruited to sites of damage or inflammation13.

Fig. 1. Systemic factors impacting myeloid cells in the MBH to regulate hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis.

Myeloid cells in the MBH are activated by HFD, which affects hypothalamic neuronal activity to regulate energy homeostasis. Myeloid cells in the MBH are exposed to the systemic circulation and are thus positioned to sense and respond to circulating factors. Diet-induced obesity (DIO) is characterized by changes in nutritional signals, inflammatory cytokines, metabolic hormones, and microbiome-derived molecules, which may modulate MBH microglial function. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Moreover, peripheral neurons can receive and convey long-distance information through complex neural circuits, forming a brain–gut axis in which visceral and vagal afferent fibers relay local signals from the gut to the brain14,15. In the brain, microglia express receptors for and have been shown to respond to neuropeptides and chemokines in addition to classical neurotransmitters16. However, vagal afferent fibers are not known to directly innervate the MBH and thus would require a more complex neuronal circuit to directly impact microglia in the MBH. Indeed, vagal afferent fibers synapse onto neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which in turn has reciprocal connections with metabolic neurons in the hypothalamus14,17. Manipulation of the vagus nerve in mice and humans has well-known effects on metabolism, but little is known about the impact of vagal inputs on the state of hypothalamic immune cells18. Given the paucity of literature in this area, we will instead focus this review on circulating factors that could allow nutritional stimuli to induce hypothalamic innate immune responses.

While the evidence supporting the causal role of the hypothalamic innate immune response in obesity comes primarily from rodent models, several studies have suggested that hypothalamic gliosis is relevant to human obesity. For example, the activation of immune cells within a specific brain area results in increased regional water content, which can be detected by quantitative MRI techniques. Given this, multiple MRI techniques to assess brain water content, including T2 relaxation time19,20, diffusion tensor imaging21, and proton density imaging22, have revealed a potential association between hypothalamic inflammation and BMI, central adiposity, and metabolic syndrome in humans20,22.

Obesity is associated with hypothalamic hypogonadism in men, and MRI indicators of hypothalamic gliosis are also inversely correlated with plasma testosterone levels23. Moreover, these imaging markers highlight a potential reduction in hypothalamic inflammation in obese individuals who experience weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery24,25. Overall, these studies provide evidence supporting the clinical relevance of hypothalamic inflammation24,25. It is, however, important to note that MRI-based indicators of inflammation in the MBH could reflect increased activation of microglia and/or astrocytes. However, human hypothalamic samples examined postmortem showed that elevated BMI is indeed associated with specific increases in microglial soma size, along with reductions in the extent of microglial ramifications, which are both morphological hallmarks of inflammatory activation26,27 that underscore the importance of microglia in human energy balance.

Myeloid cell heterogeneity in the mediobasal hypothalamus

The myeloid compartment of the CNS includes a heterogeneous population of tissue-resident macrophages, including microglia in the brain parenchyma and macrophages and dendritic cells in perivascular, meningeal, and choroid plexus compartments28,29. Microglia are the most abundant myeloid cell type in the CNS and the predominant cell type within the brain parenchyma28. CNS myeloid cells express numerous overlapping markers, and thus a major obstacle in the field has been the inability to discriminate between resident “homeostatic” microglia and the variety of other myeloid cell types in the brain. New technical approaches for single-cell profiling, however, have recently overcome this obstacle and revealed remarkable functional complexity within the CNS myeloid compartment in the context of normal health and disease30. Resident microglia are yolk sac-derived cells and self-renew within the brain throughout life, and there is increasing evidence that these cells function differently in the brain than bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages, which infiltrate the brain under conditions of CNS injury and disease31,32. Microglia are long-lived cells and depend highly on signals from their tissue environment to maintain identity, but there is growing evidence that even true microglia are not monolithic, exhibiting spatial heterogeneity and varying functional states dictated by anatomical location and physiological or pathological factors both in the rodent and human brain33. These findings have important therapeutic implications because they suggest that targeting a specific microglial subset or state may require strategies that are specific to a given brain region. Moreover, drug targeting of most parenchymal microglia is limited by the BBB. With this in mind, the MBH may provide an interesting therapeutic opportunity, as the ME and ventromedial ARC contain highly fenestrated blood vessels, which facilitate relatively open communication with the periphery1,2. Thus, myeloid cells in the MBH are potential targets that may be accessed by modulators delivered enterally, parenterally, or intranasally34. Furthermore, bloodborne (e.g., monocyte-derived) myeloid cells are recruited to the brain during pathological states that are associated with compromised BBB integrity, and these cells, once recruited into the brain parenchyma, have the capacity to gain key microglia-like characteristics28,35. As such, these infiltrating cells are also recognized as targets for therapeutic intervention in neurological disease36,37.

We used detailed immunofluorescence histochemistry and BM lineage tracing to show that the HFD-induced hypothalamic innate immune response actually involves diverse myeloid cell phenotypes and functional states with unique spatial distributions within the MBH11. Moreover, a recent study showed that inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activation in hypothalamic LysM+ macrophages contributes to the diet-driven immune response within the MBH by increasing local vascular permeability and lipid influx38. These LysM+ macrophages apparently accumulate in the MBH in response to a HFD through local proliferation, without the contribution of BM-derived cells39. Understanding the functional heterogeneity of individual myeloid cell types in the MBH, both resident and infiltrative, and the specific signaling pathways that are regulated by diet in these populations will be essential in developing selective cell-based and/or immunotherapeutics to correct diet-induced hypothalamic dysfunction.

Circulating factors that regulate hypothalamic innate immune responses

Translating knowledge of myeloid cells in the MBH for therapeutic purposes will require understanding which potential circulating factors influence the polarization of these cells. It has long been known that hypothalamic nutrient sensing is critical for the regulation of energy balance, with recent work focusing on the hypothalamic sensing of nutritional signals, especially glucose and lipids40. Hypothalamic neurons are well known to be regulated by circulating metabolic signals, and both hypothalamic neurons and glial cells have been shown to respond to lipid signals that regulate both food intake and energy homeostasis41. However, the comparative roles of the neuronal and nonneuronal compartments in this regard have not been fully elucidated. In addition to specific nutrients, this section will review the circulating hormonal, inflammatory, and microbiome-derived factors that may regulate hypothalamic immune activation in the development of diet-induced obesity (DIO).

Hormonal regulation of the hypothalamic innate immune response

There is an expanding list of peripherally generated hormones that regulate food intake and metabolism and act on hypothalamic signaling pathways15. However, the effects of these hormones, which are derived from the gut, adipose tissues, and muscle, on hypothalamic immune activation remain poorly characterized. Here, we review what is known about hormonal regulation of the hypothalamic innate immune response.

Leptin

Leptin is a peptide hormone secreted primarily by white adipocytes that is central to the regulation of body weight and energy expenditure42. While previously thought to be expressed predominantly by specific neuronal populations, including POMC and NPY/AgRP/GABA (NAG) neurons, leptin receptor mRNA has also been found in astrocytes and microglia43. Initial studies showed that while both leptin-deficient (ob/ob) and leptin receptor-deficient (db/db) mice are obese, this phenotype alone is not sufficient for mice in either model to develop microgliosis in the MBH. However, ob/ob mice develop hypothalamic microgliosis in a manner similar to that of wild-type controls when fed a HFD44. Taken together, these early results suggested that dietary excess, rather than obesity per se, mediates the activation of MBH microglia and that leptin-dependent signaling in the brain is not a dominant determinant of this response. However, there is more recent evidence suggesting that microglial reactivity may also be modulated by leptin signaling. For example, providing ob/ob mice with leptin replacement is sufficient to increase microglial numbers in the MBH44. Moreover, pretreating cultured microglia with leptin potentiates their inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and leptin increases the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-1 beta (IL‐1β) in primary hypothalamic microglia44,45. Finally, myeloid-specific deletion of the leptin receptor led to increased weight gain in mice fed a standard chow diet, although this was predominantly due to increased lean mass46. Notably, this study was performed in a noninducible genetic model, pointing to the possibility that the resulting hypothalamic and metabolic phenotypes might be influenced by impairments in synaptic pruning by microglia during embryonic and early-life development46.

Adiponectin

Adiponectin (APN) is an adipokine that is almost exclusively secreted by adipocytes47, and circulating levels of its high molecular-weight multimeric isoform are decreased in individuals with visceral adiposity and insulin resistance48. APN-deficient mice are resistant to HFD-induced obesity49. Exploration of this phenotype has revealed that APN is able to cross the BBB and stimulates food intake via activation of the two APN receptors (ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2) in the ARC; in rats, these receptors have been shown to be expressed not only in POMC and NAG neurons but also in microglia and astrocytes50,51. Notably, APN-deficient mice displayed enhanced microglial proliferation and inflammatory cytokine expression in both the hypothalamus and hippocampus following LPS injection, and this hyperresponsiveness was suppressed by i.c.v. injection of globular APN52. Treatment of mice fed a HFD for 4 weeks with systemic (i.p.) APN was associated with decreased microglial activation, as indicated by morphological changes, and decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines in the hypothalamus; however, this effect was not associated with an alteration in body weight51. Whether APN acts directly on hypothalamic microglia in vivo has not been studied.

Glucagon-like peptide 1

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a peptide hormone that is primarily secreted by enteroendocrine L-cells in the intestine53. Several GLP-1 receptor agonists have now been approved for the treatment of diabetes and/or obesity, and the anorectic effects of GLP-1, although pleiotropic, are increasingly linked to agonism of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) in multiple brain regions54. Indeed, GLP-1R is expressed by neurons, astrocytes, and microglia55,56. Within the hypothalamus, GLP-1 stimulates the activity of specific GLP-1R-expressing neuronal populations, including POMC neurons. However, GLP-1R expression by hypothalamic neurons was paradoxically dispensable in GLP-1 treatment to induce weight loss or improve glucose tolerance in mice57,58. Intriguingly, GLP-1 has direct anti-inflammatory effects on microglia, decreasing their secretion of proinflammatory cytokines59. Systemic administration of the GLP-1 analog exendin-4 and, in a separate study, liraglutide decreased microglial activation within the MBH of mice fed a HFD44,60. However, whether the beneficial effects of GLP-1R agonists are at least partly mediated by the modulation of hypothalamic microglial activation remains to be studied.

Although systemic GLP-1 can cross the BBB61, it is notable that GLP-1-producing (PPG) neurons in the NTS were recently shown to be another major source of GLP-1 within the brain62. Ablating NTS PPG neurons did not affect body weight or food intake on a standard chow diet but markedly increased feeding behavior following a fast, when food consumption rates are typically high62. Nevertheless, whether GLP-1 produced in the periphery or in the brain is more dominant in modulating the hypothalamic response to HFD has not been assessed.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone produced predominantly by the gut, but it is also expressed in other tissues, including the ARC63,64. While ghrelin has potent orexigenic effects that are mediated by NAG neurons in the ARC, it also has anti-inflammatory effects on microglia in vitro and in models of experimental autoimmune encephalitis65. In one study, pretreatment of mice with a single injection of purified ghrelin in its active acylated (n-octanoyl) form reduced the hypothalamic inflammatory response to a single day of HFD feeding66. Taken together, these results suggest that ghrelin signaling may play a role in disassociating hypothalamic microglial activation from the effects of dietary excess or perhaps even restraining it.

Estrogens

Estrogens may also serve to modulate both hypothalamic neurophysiology and the interaction between MBH neurons and local microglia. The hypothalamic microglial response to the consumption of a HFD exhibits striking sexual dimorphism in rodents, with males having higher levels of inflammatory cytokines and greater microglial activation than females67,68. There is evidence suggesting that both cell-intrinsic and environmental factors impact microglial function in a sexually dimorphic manner, and these factors may help determine sex-specific differences in susceptibility to neurological disease69. Ovariectomy-induced estrogen deficiency increases microglial activation in female mice68. In contrast, both 17-α-estradiol (17αE2) and 17-β-estradiol (17βE2) have anti-inflammatory effects on microglia in vitro, and 17αE2 treatment reduced aging-associated hypothalamic microglial activation in male mice and reduced microglial activation and accumulation within the MBH of ovariectomized female mice fed a HFD70,71. However, data also suggest that microglia show innate sexual dimorphism, independent of hormonal inputs72. Future studies should examine how such innate elements interact with environmental (hormonal, dietary) factors to functionally modulate MBH microglia.

BAIBA

β-aminoisobutyric acid (BAIBA) is a myokine that is increased by physical activity and was shown to mediate the benefits of exercise on obesity-related metabolic risk factors in mice but with only modest effects on weight gain itself73,74. A regimen of moderate exercise decreased the MBH microgliosis induced by the consumption of a high-carbohydrate HFD in LDL receptor-deficient mice75. Similarly, BAIBA treatment for 8 weeks lowered the hypothalamic mRNA levels of inflammatory genes and reduced the number of hypothalamic microglia in mice that had already been fed a HFD for 16 weeks, although it did not reverse weight gain73.

In summary, there are currently no data directly implicating circulating hormonal signals in driving the mechanism by which dietary excess causes hypothalamic innate immune activation. However, several hormones may play roles in modulating this response, with leptin being potentially proinflammatory, and most others have roles in restraining hypothalamic immune activation.

The hypothalamic innate immune response to systemic inflammation

Obesity can induce chronic systemic inflammation and increase the circulating levels of inflammatory molecules, including LPS, interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), and serum amyloid A (SAA), in certain individuals76. The levels of these factors can then rise in the MBH as well. In addition, the levels of other cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, are known to be increased in the MBH in obesity; however, these cytokines are most likely increased due to local production rather than import from the systemic circulation. Microglia express receptors and machinery that are involved in many aspects of innate immune signaling77, raising the possibility that circulating and/or local inflammatory mediators may play a role in regulating the polarization of MBH microglia in obesity. However, microglial activation in the MBH occurs rapidly in response to a HFD, and a recent study demonstrated a response as early as 6 h after exposure to a HFD78. In contrast, although some studies have demonstrated an increase in circulating inflammatory cytokines after a single high-fat meal, a recent systematic review showed that only IL-6 was consistently increased after one high-fat meal in healthy individuals79. Overall, these studies raise some doubt as to whether circulating levels of inflammatory factors rise fast enough in response to the initiation of a HFD to represent viable sources of factors that then stimulate microglial activation within the MBH. The alternative is to consider that noninflammatory factors (nutrients, microbiome-derived factors, hormones, etc.) alter the functional states of MBH microglia and that these effects precede any systemic inflammatory changes that may occur later on. Regardless, it seems likely that circulating cytokines and other immune-related signals may help regulate and modulate chronic diet-associated hypothalamic innate immune activation. Some potential signals are reviewed here.

LPS

LPS levels in the circulation can be increased by HFD consumption and remain elevated in obesity, possibly due to increased gut permeability80,81. Indeed, systemic administration of a low dose of LPS to mimic the levels seen upon chronic consumption of a HFD was sufficient to induce weight gain and insulin resistance in mice81. How peripheral LPS impacts brain function is unclear, as most of the brain is relatively protected against peripheral LPS, with an estimation that only 0.025% of an i.v. injection reaches the brain parenchyma82. A recent study showed that peripherally injected LPS is present, however, within CVOs, including the ME and that the transport of LPS into CVOs may be mediated by lipoproteins83. Thus, CVOs may function as sensors of peripheral LPS. Moreover, a single i.p. injection of LPS in mice induced the proliferation of microglia in hypothalamic CVOs, including the ME and ARC84. However, a recent study showed that while peripheral LPS injection caused microglial activation in lean animals, intermittent LPS injection decreased HFD-induced microglial activation and increased MBH astrogliosis85.

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is the cell-surface receptor for LPS and is expressed most highly by myeloid cells in the CNS, including in the hypothalamus86,87. Whole-body TLR4 knockout has shown variable effects on the response to a HFD in different studies, providing protection from weight gain in some but not in others88–90. One explanation for this discrepancy is that TLR4 deletion in different tissues may have variable effects on DIO. Intriguingly, the transplantation of TLR4-deficient BM also had variable effects on HFD-induced weight gain91–94. More recently, hepatocyte-specific targeting of TLR4 ameliorated hepatic steatosis and improved insulin resistance but did not affect weight, while macrophage-specific targeting of TLR4 did not protect mice from DIO, insulin resistance or hepatic steatosis95. In the hypothalamus, TLR4 targeting through stereotactic injection of TLR4 shRNA lentiviral particles into the ARC decreased microglial accumulation and body weight gain during 4 weeks of HFD feeding96. Daily intraperitoneal injection of a TLR4-inhibiting antibody to animals on a HFD decreased weight gain and the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the MBH97. However, microglia-specific TLR4 deficiency has not been examined in a mouse model of DIO. It has been previously hypothesized that TLR4 may also mediate innate immune activation in DIO by functioning as a direct receptor of saturated fatty acids (SFAs). However, a recent study demonstrated that while TLR4 may be required for SFA-induced innate immune activation, it is not an SFA receptor. Rather, TLR4 is required for priming cells for SFA-induced inflammatory responses98. The question remains whether increased LPS levels in the context of DIO are necessary for TLR4-dependent priming of microglia to drive hypothalamic inflammatory responses in vivo.

IL-6

IL-6 is a cytokine associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Indeed, acute IL-6 infusion is sufficient to induce insulin resistance in mice99. Interestingly, myeloid-specific depletion of the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) causes a shift toward M1 macrophage polarization in liver, white adipose tissue, and brown adipose tissue. Moreover, this polarization shift in macrophage populations is associated with impaired glucose homeostasis100. However, the effects of chronically increased systemic levels of IL-6 are pleiotropic and include some beneficial consequences, depending on the model101. For example, IL-6-deficient mice paradoxically develop maturity-onset obesity, and central IL-6 administration was able to increase energy expenditure in this model102.

When delivered into the CNS (i.c.v. injection), IL-6 decreased feeding and improved glucose homeostasis, but deleting IL-6R in neurons did not block these effects103. Moreover, CNS delivery of an antibody that inhibits IL-6 signaling blocked the anti-inflammatory effect of exercise on the hypothalamus104. Glycoprotein 130 (gp130) is the transmembrane receptor for IL-6 trans-signaling, which is engaged by IL-6 binding to soluble IL-6R. Targeting gp130 in neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus blocked the metabolic effects of central IL-6 administration103. The cellular source of soluble IL-6R that mediates IL-6 trans-signaling in the brain has not been found, but IL-6R mRNA is most highly expressed by microglia86. Interestingly, IL-6 trans-signaling was also essential in the neuroprotective effects of microglia in a model of traumatic brain injury105. IL-6 is released at high levels by exercised muscle106; however, multiple brain cell types may synthesize IL-6 locally107. Whether systemic and/or local IL-6 are involved in the regulation of hypothalamic function remains unknown. Further functional resolution of cell- and tissue-specific IL-6 signaling pathways will be important in determining why acute and chronic manipulations of IL-6, whether systemically or specifically in the CNS, produce wide-ranging and seemingly paradoxical effects on obesity.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) is produced by adipose tissues, and the levels are elevated in both adipose tissues and plasma in obesity108. Both genetic deletion and pharmacologic inhibition of PAI-1 protect against HFD-induced increases in food intake and body weight109,110, and this effect was found to be mediated at least in part by impaired leptin signaling in the hypothalamus109. The effects of PAI-1 on MBH immune activation have not been explored; however, PAI-1 has been shown to promote microglial migration and regulate phagocytosis111.

In summary, there are intriguing data suggesting that circulating immune-related factors may modulate the hypothalamic innate immune response by acting on microglia. However, detailed and systematic studies to determine how these factors might coordinately mediate hypothalamic dysfunction and the development of DIO have not yet been performed.

Dietary composition and regulation of the hypothalamic innate immune response

The effects of specific macronutrient proportions on obesity remain a subject of controversy and ongoing investigation. Most diets used to produce obesity in rodents are high in saturated fat; however, these diets contain significant calories from sugar as well. A recent systematic evaluation of the effect of macronutrient composition on body weight regulation showed that in mice, increased dietary fat content but not protein or carbohydrate content was associated with increased food intake and weight gain, plateauing with diets in which 60% of calories come from fat112. Importantly, this systematic comparison was performed in male C57BL/6J mice, which are sensitive to both DIO and HFD-induced hypothalamic innate immune activation, and it is unclear how transferrable these findings are to other mouse strains. Moreover, interpersonal differences in obesity-susceptibility genotypes have been shown to interact with dietary macronutrient composition to produce an integrated obesity risk profile in humans113,114. Thus, rodent experiments exploring the effects of macronutrient composition on aspects of DIO must be interpreted with these key limitations in mind.

Large-scale systematic evaluations of the effects of macronutrient composition on the activation state of hypothalamic immune cell types have not been performed, and most studies used standard HFDs varying from 40 to 60% of caloric intake from fat with the source of fat predominantly being either milk fat or animal lard, which are both high in saturated fat (Table 1). Common diets that have been demonstrated to induce hypothalamic innate immune activation include D12451 (Research Diets, 45% kCal fat, lard), 88137 (Teklad, 42% kCal fat, milk fat), and D12492 (Research Diets, 60% kCal fat, lard) (Table 1)115–117. These diets have been shown to increase the levels of hypothalamic inflammatory cytokines and promote microglial activation and also lead to increased caloric intake. This raises the question of whether increased caloric intake per se causes hypothalamic immune activation. However, calorically matched pair-feeding experiments with distinct HFDs demonstrate that consuming excess dietary fat is sufficient to cause weight gain and hypothalamic innate immune activation independent of overall caloric consumption117.

Table 1.

Dietary composition of high-fat diets used for studying hypothalamic innate immune response.

| Diets (Manufacturer) | caloric content (kcal/g) | %Fat (kcal) | %Carb (kcal) | %Prot (kcal) | Fat source | % SFA | microglial changes | MBH inflammatory cytokines | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | N | TNF | IL1β | IL6 | ||||||||

| D12492(RD) | 5.21 | 60 | 20 | 20 | Lard | 33% | + | + | + | + | + | 27,38,66,68,71 |

| D12451(RD) | 4.7 | 45 | 35 | 20 | Lard | 30% | + | + | + | + | + | 11,19 |

| D12331(RD) | 5.56 | 58 | 25 | 17 | Coconut oil | 82% | + | + | + | + | + | 140 |

| TD.88137(Envigo) | 4.5 | 42 | 43 | 15 | Milk fat | 62% | + | + | + | + | + | 10 |

| D11012901(RD) | 4.4 | 32 | 51 | 17 | Coconut oil | 75% | NR | NR | +a | −a | −a | 118 |

| D11061301(RD) | 4.4 | 32 | 51 | 17 | Butter | 60% | NR | NR | −a | +a | +a | 118 |

| D11012902(RD) | 4.4 | 32 | 51 | 17 | Olive oil | 20% | NR | NR | −a | −a | −a | 118 |

| HCHF1(NR) | 5.56 | 58 | 25 | 17 | Coconut oil | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | 120 |

| HCHF2(NR) | 5.08 | 62 | 19 | 19 | Beef tallow | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | 120 |

| LCHF1(Kliba Nafag) | 6.17 | 79 | 2 | 19 | Beef tallow | 68% | − | + | NR | NR | NR | 120 |

| LCHF2(Kliba Nafag) | 7.2 | 93 | 2 | 6 | Beef tallow | 60% | − | − | NR | NR | NR | 120 |

RD Research Diets, Inc., OY Oriental Yeast Co., M morphology, N number, NR not reported.

aInflammatory cytokines compared amongst HFD compositions without low-fat control.

Several studies have also examined the effects of the amount and source of saturated fat in the diet on hypothalamic innate immune activation. One study compared the effects of diets that were low in saturated fat (corn and olive oil, 20% of total fat calories as saturated fat), high in saturated fat of plant origin (coconut oil, 75% saturated fat), or high in saturated fat of animal origin (butter, 60% saturated fat) (Table 1)118. While there was no difference in adipose tissue inflammatory markers, animals on both types of high-saturated fat diets showed increased levels of inflammatory cytokine expression in the hypothalamus118. In another comparison of diets with similar macronutrient compositions, a diet with elevated levels of saturated fat caused a more rapid increase in food intake than did one with lower saturated fat content119. Moreover, in a direct comparison of two diets, one of animal origin and one containing olive oil, which is high in monounsaturated oleic acid, only the diet with animal fat caused increased inflammatory cytokine expression and myeloid cell immunostaining in the MBH, although the total fat content of both diets was matched at 36% of overall calories97. Thus, the available evidence suggests that high-saturated fat intake is required for a HFD to induce hypothalamic innate immune activation in mice. Furthermore, it was shown that even very short-term (1–6 h) exposure to excess dietary saturated fat is sufficient to induce changes in MBH microglia78. These studies suggest that the composition of consumed fat, rather total fat intake, regulates immune activation in the hypothalamus in promoting DIO. The rapidity of this response is consistent with a direct effect of dietary saturated fat.

A recent study explored the role of dietary carbohydrates in the pathogenesis of MBH innate immune activation using high-fat diets with either low or high amounts of carbohydrates. Neither of the two very low carbohydrate diets used in this study, a nonketogenic diet (LCHF1) and a ketogenic diet (LCHF2), were able to induce MBH microgliosis or weight gain (Table 1)120. Another low carbohydrate, high-fat diet (D11111601, Research Diets) suppressed both the increased microglial cell division seen in the MBH and the increased food intake produced by the consumption of a standard HFD (D12492)121. These studies suggest that very low carbohydrate intake can protect against HFD-induced MBH innate immune activation.

Our group has explored the specificity of saturated fat in mediating the MBH innate immune response by direct gavage into the stomachs of mice. Gavage with milk fat, which is high in palmitic acid, but not olive oil reproduced the MBH microglial response observed following the consumption of a HFD enriched in saturated fat10. Moreover, the inflammatory effects of dietary fats administered into the brain (i.c.v.) are linked to specific SFAs97,122. In contrast, i.c.v. administration of oleic acid actually decreased food intake and hepatic glucose production compared with the control123. Hypothalamic sensing of oleic acid appears to be mediated by the regulation and sensing of intracellular long-chain fatty acyl-CoA levels by MBH neurons124. There is no known role for MBH microglia in the hypothalamic sensing of oleic acid; however, short-term (3 days) HFD feeding abolishes the metabolic and anorexigenic effects of i.c.v. oleic acid administration125. Of course, i.c.v. injection is an artificial model, but there is evidence that the hypothalamic lipid composition reflects dietary fat composition over time. Radiolabeled palmitic acid delivered enterally and lipoproteins injected i.v. were both able to rapidly enter the MBH10,126.

Further supporting a direct role for SFAs in functionally regulating hypothalamic microglia, multiple groups have demonstrated that saturated but not unsaturated FAs have proinflammatory effects on cultured microglia127. We showed that treating organotypic hypothalamic slices with palmitic acid but not oleic acid initiates an inflammatory response in the hypothalamic slice, which requires the presence of microglia10. Indeed, oleic acid cotreatment abrogated the proinflammatory response of these slices to palmitic acid treatment. Thus, saturated fat itself may function as an immunomodulatory signal that is delivered via the systemic circulation to mediate hypothalamic innate immune activation in DIO.

Microglia are regulated by microbiome-derived factors

The gut microbiome is increasingly accepted to be an environmental factor linked to obesity and associated metabolic disorders. The diverse gastrointestinal microbial community participates in energy extraction from food, host lipid metabolism, immune responses, and endocrine function128. These observations were made using germ-free (GF) mice that were maintained in a sterile environment without a gut microbiome. GF mice are leaner than specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice despite consuming more calories. Furthermore, transplanting the microbiota from SPF mice into GF mice increased body fat by 60% within 2 weeks129. Indeed, the gut microbiome regulates both host energy expenditure and feeding behavior130. In humans, obesity, by contrast, produces a gut microbiome that is less diverse and consumes less energy than that of lean individuals131. Genetically obese mice (ob/ob) have a higher proportion of intestinal Firmicutes and 50% fewer Bacteroidetes and a parallel enrichment of microbial genes involved in polysaccharide degradation than in the microbiomes of lean siblings132.

The gut microbiome also controls the activity of CNS myeloid cells. Disruption of the gut microbiome resulted in significant alterations in microglial function in both GF mice and mice in which the microbiome was ablated by antibiotic treatment133,134, indicating that microglia may continuously sense inputs emanating from the gut microbiome. For instance, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are the main metabolites produced by the bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber in the gastrointestinal tract, and these SCFAs are rapidly absorbed by colonic cells. SCFAs influence gut–brain communication and brain function directly or indirectly through immune, endocrine, and vagal pathways135. Although SCFAs have been shown to protect against DIO in mice136 and overweight humans137, the underlying mechanisms are unclear. SCFAs are important regulators of innate immune responses and were recently shown to be involved in regulating microglial function. Indeed, GF mice display globally defective microglial phenotypes, leading to impaired CNS immune responsiveness. Remarkably, aspects of normal microglial homeostasis can be restored when GF mice are supplemented with SCFAs in their drinking water133. Furthermore, recent work suggests that microglial activity is directly regulated by the metabolites of dietary tryptophan metabolism produced by commensal gut flora and that this response controls a downstream inflammatory response in astrocytes138.

The gut microbiota is also affected by circadian rhythms, with some microbes showing diurnal fluctuations in their relative abundance and activity139. Microglia in the MBH are also affected by the intrinsic circadian clock, with microglial numbers and activity being increased in the dark relative to the light phase in mice under standard housing conditions140. However, it remains unknown whether any aspect of circadian regulation of microglial numbers or activity, particularly within the hypothalamus, is a function of the circadian aspects of the gut microbiome. Building on a wealth of information highlighting microglia and other CNS myeloid cell types as crucial mediators linking the gut microbiome to pathological outcomes in the context of several neurodegenerative disease models141, future studies will need to comprehensively evaluate how the composition, secretome, and circadian regulation of the gut microbiome interact to regulate hypothalamic control of energy and glucose homeostasis.

Novel tools to target distinct CNS immune cell subsets

The most commonly used mouse line to manipulate microglia is based on the Cx3cr1 (encoding fractalkine receptor) promoter, and Cx3cr1CreER mouse strains have substantially advanced the microglial field. However, Cx3cr1 gene expression within the CNS is not restricted to microglia, as it is also expressed in nonparenchymal macrophages at CNS border locations142. Furthermore, Cx3cr1 has been shown to be expressed by long-lived peripheral tissue-resident myeloid cell types143,144. Therefore, the results obtained using this mouse model in reference to microglia should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, this mouse line was generated based on knock-in strategies in which the endogenous gene is replaced, and there is evidence that Cx3cr1 haploinsufficiency affects microglial function145,146. Thus, more specific tools to label and manipulate microglia are needed to further understand how this cell type contributes to brain health and disease.

Recent advances in RNA sequencing and other profiling technologies have revealed new insights into CNS myeloid cells, including a greater degree of heterogeneity than had been previously recognized. This information has been used to attempt to develop better mouse tools. Single-cell RNA-sequencing studies identified distinct core signature genes for microglia, such as Sall1, Tmem119, P2ry12, and Hexb. Sall1, a conserved transcriptional regulator, emerged as a marker to distinguish bona fide parenchymal microglia from other brain myeloid cells147. However, Sall1CreER transgenic mice show prominent recombination in the neuroectodermal lineage148. Transmembrane protein 119 (Tmem119), a cell-surface protein, was also recently identified as a novel microglia-specific marker that is not expressed by peripheral myeloid cells149. However, a recent targeting approach revealed ectopic expression of Tmem119 in CD34+ vessels in the CNS and leptomeningeal pial cells150. P2ry12CreER transgenic mice have been recently described151. Since P2ry12 expression has been shown to be downregulated upon microglial activation152, this new mouse line will be particularly useful for tracking microglia during disease and development. Furthermore, hexosaminidase subunit beta (Hexb) is a highly enriched microglial gene with only minimal expression by other brain myeloid cell types, even in models of neuroinflammatory diseases. The Hexb locus has been used for the generation of two promising transgenic mouse lines: the HexbtdT and HexbCreERT2 strains153.

Despite these impressive recent advances, the use of single promoter activity could be insufficient to specifically target a desired population of microglia. To overcome this problem, a second dimension of recombination, such as using the “split-Cre” system where Cre recombinase expression is regulated by coincidental activity of two different promoters, increasing the specificity of Cre-mediated DNA recombination154, could be highly effective. Such a binary transgenic system involving complementation-competent NCre and CCre fragments whose expression is driven by distinct promoters was recently used to specifically target parenchymal microglia using Sall1NCre:Cx3cr1CCre mice and perivascular macrophages using Lyve1NCre:Cx3cr1CCre mice155 simultaneously.

Such new and more specific tools will be necessary for further experiments to identify the specific myeloid cell populations in the MBH that are responsible for the initial and ongoing hypothalamic immune activation in response to dietary excess.

Concluding remarks and future directions

The hypothalamic innate immune response is a component of DIO, and evidence suggests that myeloid cells, particularly microglia, are critical cellular drivers of this process. Recent studies have focused on the role of myeloid cells within the MBH in the pathogenesis of DIO. It is tempting to focus on myeloid cells in the MBH due to their position within hypothalamic CVOs, making them more amenable to drug targeting. However, currently available tools target microglia throughout the CNS. Thus, the specificity of MBH microglia in the pathogenesis of obesity compared to that of microglia in other brain regions, especially other CVOs positioned to sense circulating signals, remains intriguing.

How does innate immune activation in the MBH induce changes in neuronal activity to cause obesity? Hypothalamic neurons sense and integrate diverse signals to regulate energy homeostasis. For example, we showed that depleting microglia decreased SFA-induced neuronal injury and leptin resistance in ARC neurons and decreased SFA-induced hyperphagia10. However, the precise mechanism by which microglia interact with hypothalamic neurons remains largely unstudied. New tools aimed at real-time monitoring of hypothalamic neuronal function will enhance our ability to study the effects of microglia. A recent study utilizing fiber photometry and optogenetics to probe the effects of DIO on NAG neuronal circuits revealed complex changes in NAG neuronal sensitivity and downstream pathways156. These new tools will be central to probing how MBH innate immune activation impacts these HFD-induced changes in hypothalamic neuronal circuits.

Furthermore, it remains unclear what aspects of microglial physiology are integral to the obesity-inducing effects of the MBH innate immune response. General phagocytic function and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines have been postulated to be involved; however, recent work has shown that microglia have complex interactions with neurons, including selective phagocytosis of presynaptic structures and the induction of postsynaptic spine head filopodia157. Microglial phagocytosis in the context of synaptic pruning is tightly regulated. For example, the classical complement protein C1q is produced by microglia and tags synapses for elimination by microglia, both in the context of normal development and degenerative disease158. Another recent study showed that in the context of neuronal injury, microglia form specialized somatic junctions with neuronal cell bodies and that these connections are important for the neuroprotective role of microglia in brain injury159. How are these functions of microglia altered by a HFD to affect hypothalamic neurons? In addition, the heterogeneity of CNS myeloid cells has become apparent with the recent identification of disease-associated microglia (DAM) and lipid droplet-accumulating microglia (LDAM), which may play major roles in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases160,161. Further understanding of the heterogeneity of myeloid cells in the MBH will enhance our understanding of how microglial activation impacts hypothalamic neuronal pathways in the regulation of appetite and systemic metabolism.

With extensive ongoing work to target obesity-associated hormones, systemic inflammation, and the microbiome in the treatment of obesity, it is essential that we understand how these systemic and circulating factors influence the hypothalamic innate immune response. An improved understanding of the mechanisms by which myeloid cells in the MBH are activated by a HFD and modulate neuronal function to regulate obesity will allow more targeted experiments to understand the role of systemic factors in modulating this response.

Author contributions

A. Folick, R.T. Cheang, M. Valdearcos, and S.K. Koliwad wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martin Valdearcos, Email: Martin.ValdearcosContreras@ucsf.edu.

Suneil K. Koliwad, Email: Suneil.Koliwad@ucsf.edu

References

- 1.Rodríguez EM, Blázquez JL, Guerra M. The design of barriers in the hypothalamus allows the median eminence and the arcuate nucleus to enjoy private milieus: the former opens to the portal blood and the latter to the cerebrospinal fluid. Peptides. 2010;31:757–776. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciofi P. The arcuate nucleus as a circumventricular organ in the mouse. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;487:187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kälin S, et al. Hypothalamic innate immune reaction in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015;11:339–351. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reardon C, Murray K, Lomax AE. Neuroimmune communication in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:2287–2316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godinho-Silva C, Cardoso F, Veiga-Fernandes H. Neuro-immune cell units: a new paradigm in physiology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019;37:19–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolicelli RC, et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333:1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer DP, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalancette-Hébert M, Gowing G, Simard A, Weng YC, Kriz J. Selective ablation of proliferating microglial cells exacerbates ischemic injury in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2596–2605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5360-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coull JAM, et al. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valdearcos M, et al. Microglia dictate the impact of saturated fat consumption on hypothalamic inflammation and neuronal function. Cell Rep. 2014;9:2124–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valdearcos M, et al. Microglial inflammatory signaling orchestrates the hypothalamic immune response to dietary excess and mediates obesity susceptibility. Cell Metab. 2017;26:185–197.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P. Gut microbiota and the neuroendocrine system. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0600-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaitin DA, et al. Lipid-associated macrophages control metabolic homeostasis in a Trem2-dependent manner. Cell. 2019;178:686–698.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning KN, Verheijden S, Boeckxstaens GE. The vagus nerve in appetite regulation, mood, and intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:730–744. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi C-X, Tschöp MH. Brain-gut-adipose-tissue communication pathways at a glance. Dis. Model. Mech. 2012;5:583–587. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szepesi Z, Manouchehrian O, Bachiller S, Deierborg T. Bidirectional microglia-neuron communication in health and disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:323. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su M, Yan M, Gong Y. Ghrelin fiber projections from the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus into the dorsal vagal complex and the regulation of glycolipid metabolism. Neuropeptides. 2019;78:101972. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2019.101972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masi EB, Valdés-Ferrer SI, Steinberg BE. The vagus neurometabolic interface and clinical disease. Int. J. Obes. 2018;42:1101–1111. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thaler JP, et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schur EA, et al. Radiologic evidence that hypothalamic gliosis is associated with obesity and insulin resistance in humans. Obesity. 2015;23:2142–2148. doi: 10.1002/oby.21248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puig J, et al. Hypothalamic damage is associated with inflammatory markers and worse cognitive performance in obese subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:E276–E281. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kullmann, S. et al. Investigating obesity-associated brain inflammation using quantitative water content mapping. J. Neuroendocrinol. 32, e12907 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Berkseth KE, et al. Hypothalamic gliosis by MRI and visceral fat mass negatively correlate with plasma testosterone concentrations in healthy men. Obesity. 2018;26:1898–1904. doi: 10.1002/oby.22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hankir MK, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery progressively alters radiologic measures of hypothalamic inflammation in obese patients. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e131329. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van de Sande-Lee S, et al. Radiologic evidence that hypothalamic gliosis is improved after bariatric surgery in obese women with type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Obes. 2020;44:178–185. doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalsbeek MJ, et al. The impact of antidiabetic treatment on human hypothalamic infundibular neurons and microglia. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e133868. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baufeld C, Osterloh A, Prokop S, Miller KR, Heppner FL. High-fat diet-induced brain region-specific phenotypic spectrum of CNS resident microglia. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:361–375. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1595-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herz J, Filiano AJ, Smith A, Yogev N, Kipnis J. Myeloid cells in the central nervous system. Immunity. 2017;46:943–956. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prinz M, Erny D, Hagemeyer N. Ontogeny and homeostasis of CNS myeloid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:385–392. doi: 10.1038/ni.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prinz M, Priller J, Sisodia SS, Ransohoff RM. Heterogeneity of CNS myeloid cells and their roles in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginhoux F, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheng J, Ruedl C, Karjalainen K. Most tissue-resident macrophages except microglia are derived from fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2015;43:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gosselin D, et al. An environment-dependent transcriptional network specifies human microglia identity. Science. 2017;356:eaal3222. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dodd GT, et al. Intranasal targeting of hypothalamic PTP1B and TCPTP reinstates leptin and insulin sensitivity and promotes weight loss in obesity. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2905–2922.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H-R, et al. Fate mapping via CCR2-CreER mice reveals monocyte-to-microglia transition in development and neonatal stroke. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabb2119. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolborea M, Pollatzek E, Benford H, Sotelo-Hitschfeld T, Dale N. Hypothalamic tanycytes generate acute hyperphagia through activation of the arcuate neuronal network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:14473–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919887117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenz KM, Nelson LH. Microglia and beyond: innate immune cells as regulators of brain development and behavioral function. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:698. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CH, et al. Hypothalamic macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase mediates obesity-associated hypothalamic inflammation. Cell Rep. 2018;25:934–946.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CH, et al. Cellular source of hypothalamic macrophage accumulation in diet-induced obesity. J. Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:221. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruciani-Guglielmacci C, Fioramonti X. Editorial: brain nutrient sensing in the control of energy balance: new insights and perspectives. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:51. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Foll C. Hypothalamic fatty acids and ketone bodies sensing and role of FAT/CD36 in the regulation of food intake. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:1036. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan WW, Myers MG. Leptin and the maintenance of elevated body weight. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018;19:95–105. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujita Y, Yamashita T. The effects of leptin on glial cells in neurological diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:828. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, et al. Hormones and diet, but not body weight, control hypothalamic microglial activity. Glia. 2014;62:17–25. doi: 10.1002/glia.22580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafrance V, Inoue W, Kan B, Luheshi GN. Leptin modulates cell morphology and cytokine release in microglia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010;24:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y, et al. Deficiency of leptin receptor in myeloid cells disrupts hypothalamic metabolic circuits and causes body weight increase. Mol. Metab. 2018;7:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weyer C, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:1930–1935. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kubota N, et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 2007;6:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guillod-Maximin E, et al. Adiponectin receptors are expressed in hypothalamus and colocalized with proopiomelanocortin and neuropeptide Y in rodent arcuate neurons. J. Endocrinol. 2009;200:93–105. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H, Tu TH, Park BS, Yang S, Kim JG. Adiponectin reverses the hypothalamic microglial inflammation during short-term exposure to fat-rich diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5738. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicolas S, et al. Globular adiponectin limits microglia pro-inflammatory phenotype through an AdipoR1/NF-κB signaling pathway. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:352. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanoski SE, Fortin SM, Arnold M, Grill HJ, Hayes MR. Peripheral and central GLP-1 receptor populations mediate the anorectic effects of peripherally administered GLP-1 receptor agonists, liraglutide and exendin-4. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3103–3112. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwai T, Ito S, Tanimitsu K, Udagawa S, Oka J-I. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits LPS-induced IL-1beta production in cultured rat astrocytes. Neurosci. Res. 2006;55:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spielman LJ, Gibson DL, Klegeris A. Incretin hormones regulate microglia oxidative stress, survival and expression of trophic factors. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2017;96:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burmeister MA, et al. The hypothalamic glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor is sufficient but not necessary for the regulation of energy balance and glucose homeostasis in mice. Diabetes. 2017;66:372–384. doi: 10.2337/db16-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Secher A, et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:4473–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI75276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon G, Kim Y-K, Song J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 suppresses neuroinflammation and improves neural structure. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;152:104615. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barreto-Vianna ARC, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Effects of liraglutide in hypothalamic arcuate nucleus of obese mice. Obesity. 2016;24:626–633. doi: 10.1002/oby.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V, Pan W. Interactions of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) with the blood-brain barrier. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2002;18:7–14. doi: 10.1385/JMN:18:1-2:07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holt MK, et al. Preproglucagon neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract are the main source of brain GLP-1, mediate stress-induced hypophagia, and limit unusually large intakes of food. Diabetes. 2019;68:21–33. doi: 10.2337/db18-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kojima M, et al. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu S, et al. Immunocytochemical observation of ghrelin-containing neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;321:157–160. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu F, Li Z, He X, Yu H, Feng J. Ghrelin attenuates neuroinflammation and demyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis involving NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway and pyroptosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:1320. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Waise TMZ, et al. One-day high-fat diet induces inflammation in the nodose ganglion and hypothalamus of mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;464:1157–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morselli E, et al. A sexually dimorphic hypothalamic response to chronic high-fat diet consumption. Int. J. Obes. 2016;40:206–209. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dorfman MD, et al. Sex differences in microglial CX3CR1 signalling determine obesity susceptibility in mice. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14556. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han J, Fan Y, Zhou K, Blomgren K, Harris RA. Uncovering sex differences of rodent microglia. J. Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:74. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02124-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sadagurski M, Cady G, Miller RA. Anti-aging drugs reduce hypothalamic inflammation in a sex-specific manner. Aging Cell. 2017;16:652–660. doi: 10.1111/acel.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Butler MJ, Perrini AA, Eckel LA. Estradiol treatment attenuates high fat diet-induced microgliosis in ovariectomized rats. Horm. Behav. 2020;120:104675. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Villa A, et al. Sex-specific features of microglia from adult mice. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3501–3511. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park BS, et al. Beta-aminoisobutyric acid inhibits hypothalamic inflammation by reversing microglia activation. Cells. 2019;8:1609. doi: 10.3390/cells8121609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roberts LD, et al. β-Aminoisobutyric acid induces browning of white fat and hepatic β-oxidation and is inversely correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors. Cell Metab. 2014;19:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yi C-X, et al. Exercise protects against high-fat diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation. Physiol. Behav. 2012;106:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doens D, Fernández PL. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid β for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cansell C, et al. Dietary fat exacerbates postprandial hypothalamic inflammation involving glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells and microglia in male mice. Glia. 2020;69:42–60. doi: 10.1002/glia.23882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Emerson SR, et al. Magnitude and timing of the postprandial inflammatory response to a high-fat meal in healthy adults: a systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2017;8:213–225. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Erridge C, Attina T, Spickett CM, Webb DJ. A high-fat meal induces low-grade endotoxemia: evidence of a novel mechanism of postprandial inflammation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;86:1286–1292. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cani PD, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Banks WA, Robinson SM. Minimal penetration of lipopolysaccharide across the murine blood-brain barrier. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010;24:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vargas-Caraveo A, et al. Lipopolysaccharide enters the rat brain by a lipoprotein-mediated transport mechanism in physiological conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13113. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13302-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furube E, Kawai S, Inagaki H, Takagi S, Miyata S. Brain Region-dependent Heterogeneity and Dose-dependent Difference in Transient Microglia Population Increase during Lipopolysaccharide-induced Inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2203. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20643-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang H-T, Chen P-S, Kuo Y-M, Tzeng S-F. Intermittent peripheral exposure to lipopolysaccharide induces exploratory behavior in mice and regulates brain glial activity in obese mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:163. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01837-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Y, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reis WL, Yi C-X, Gao Y, Tschöp MH, Stern JE. Brain innate immunity regulates hypothalamic arcuate neuronal activity and feeding behavior. Endocrinology. 2015;156:1303–1315. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pierre N, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 knockout mice are protected against endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by a high-fat diet. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dalby MJ, et al. Diet induced obesity is independent of metabolic endotoxemia and TLR4 signalling, but markedly increases hypothalamic expression of the acute phase protein, SerpinA3N. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15648. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33928-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Camandola S, Mattson MP. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates fat, sugar, and umami taste preference and food intake and body weight regulation. Obesity. 2017;25:1237–1245. doi: 10.1002/oby.21871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coenen KR, et al. Impact of macrophage toll-like receptor 4 deficiency on macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and the artery wall in mice. Diabetologia. 2009;52:318–328. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Razolli DS, et al. TLR4 expression in bone marrow-derived cells is both necessary and sufficient to produce the insulin resistance phenotype in diet-induced obesity. Endocrinology. 2015;156:103–113. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saberi M, et al. Hematopoietic cell-specific deletion of toll-like receptor 4 ameliorates hepatic and adipose tissue insulin resistance in high-fat-fed mice. Cell Metab. 2009;10:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Orr JS, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency promotes the alternative activation of adipose tissue macrophages. Diabetes. 2012;61:2718–2727. doi: 10.2337/db11-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jia L, et al. Hepatocyte Toll-like receptor 4 regulates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3878. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhao Y, Li G, Li Y, Wang Y, Liu Z. Knockdown of tlr4 in the arcuate nucleus improves obesity related metabolic disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7441. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07858-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Milanski M, et al. Saturated fatty acids produce an inflammatory response predominantly through the activation of TLR4 signaling in hypothalamus: implications for the pathogenesis of obesity. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:359–370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2760-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lancaster GI, et al. Evidence that TLR4 is not a receptor for saturated fatty acids but mediates lipid-induced inflammation by reprogramming macrophage metabolism. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1096–1110.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim H-J, et al. Differential effects of interleukin-6 and -10 on skeletal muscle and liver insulin action in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1060–1067. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mauer J, et al. Signaling by IL-6 promotes alternative activation of macrophages to limit endotoxemia and obesity-associated resistance to insulin. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:423–430. doi: 10.1038/ni.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wueest S, Konrad D. The controversial role of IL-6 in adipose tissue on obesity-induced dysregulation of glucose metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;319:E607–E613. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00306.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wallenius V, et al. Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nat. Med. 2002;8:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Timper K, et al. IL-6 improves energy and glucose homeostasis in obesity via enhanced central IL-6 trans-signaling. Cell Rep. 2017;19:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ropelle ER, et al. IL-6 and IL-10 anti-inflammatory activity links exercise to hypothalamic insulin and leptin sensitivity through IKKbeta and ER stress inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 105.Willis EF, et al. Repopulating microglia promote brain repair in an IL-6-dependent manner. Cell. 2020;180:833–846.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chowdhury S, et al. Muscle-derived interleukin 6 increases exercise capacity by signaling in osteoblasts. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2888–2902. doi: 10.1172/JCI133572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Aniszewska A, et al. The expression of interleukin-6 and its receptor in various brain regions and their roles in exploratory behavior and stress responses. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015;284:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Alessi M-C, Juhan-Vague I. PAI-1 and the metabolic syndrome: links, causes, and consequences. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:2200–2207. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242905.41404.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hosaka S, et al. Inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 activation suppresses high fat diet-induced weight gain via alleviation of hypothalamic leptin resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:943. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ma L-J, et al. Prevention of obesity and insulin resistance in mice lacking plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Diabetes. 2004;53:336–346. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jeon H, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 regulates microglial motility and phagocytic activity. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:149. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hu S, et al. Dietary fat, but not protein or carbohydrate, regulates energy intake and causes adiposity in mice. Cell Metab. 2018;28:415–431.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Corella D, et al. APOA2, dietary fat, and body mass index: replication of a gene-diet interaction in 3 independent populations. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:1897–1906. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.San-Cristobal R, Navas-Carretero S, Martínez-González MÁ, Ordovas JM, Martínez JA. Contribution of macronutrients to obesity: implications for precision nutrition. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020;16:305–320. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.De Souza CT, et al. Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4192–4199. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Morselli E, et al. Hypothalamic PGC-1α protects against high-fat diet exposure by regulating ERα. Cell Rep. 2014;9:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Posey KA, et al. Hypothalamic proinflammatory lipid accumulation, inflammation, and insulin resistance in rats fed a high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;296:E1003–E1012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90377.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maric T, Woodside B, Luheshi GN. The effects of dietary saturated fat on basal hypothalamic neuroinflammation in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014;36:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sasaki T, et al. A central-acting connexin inhibitor, INI-0602, prevents high-fat diet-induced feeding pattern disturbances and obesity in mice. Mol. Brain. 2018;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao Y, et al. Dietary sugars, not lipids, drive hypothalamic inflammation. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]