Abstract

Gold nanoparticle (AuNP)-based optical assays are of significant interest since the molecular phenomenon can be examined easily with change in the color of AuNPs. Herein, we report the development of a dipstick using a AuNP-labeled single-chain fragment variable (scFv) antibody for the detection of morphine. The scFv antibodies for morphine were developed using phage display-based antibody library. Immunoglobulin variable regions of heavy (VH)- and light (VL)-chain genes were connected via a glycine–serine linker isolated from murine immune repertoire and cloned into the expression vector pIT2. The scFv was produced in Escherichia coli HB2151, yielding a functional protein with a molecular weight of approximately 32 kDa. The morphine scFv was labeled with gold nanoparticles and used as an optical immunoprobe in a dipstick. The competitive dipstick assay characterized the ability of the scFv antibody to recognize free morphine. The detection range was 1–1000 ng mL−1 with a limit of detection (LOD) of 5 ng mL−1 under optimal conditions, and the IC50 value was 14 ng mL−1 for morphine. The developed optical dipstick kit of scFv antibody was capable of specifically binding to free morphine and its analogs in a solution in less than 5 min and could be useful for on-site screening of a real sample in blood, urine, and saliva.

Dipstick device developed on the principle of lateral flow using gold nanoparticles for analysis of morphine in urine by morphine/scFv/immunoprobe.

Introduction

Heroin rapidly degrades to morphine after deacetylation into monoacetyl morphine (MAM).1 Glucuronidation of morphine occurs in the liver, where it results in the formation of morphine-3-glucuronide (M-3-G) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M-6-G).2 Morphine is an important analgesic and narcotic used in medicine; hence, it can be used as an indicator of drug abuse.3 Thus, there is a need to develop alternative, simple, and easy approaches to monitor these opiate drugs in biological samples. A number of chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques have been developed for monitoring of opiate drugs.4,5 However, most of these techniques are time consuming and complex, require trained personnel, and are not amenable to on-site applications. Various electrochemical, fluorescence-based methods are favored using antibodies for the identification or quantification of opiates as they are highly sensitive, specific, and robust.6–9 Previously, either polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies were used to conduct immunological assays for opiate drugs.10–12 These methods were based on sandwich immunoassay for the detection of multivalent antigen.13 In recent times, photoelectrochemical immunoassays have attracted significant attention due to their low cost and high sensitivity.14 Recently, recombinant DNA technology was used for the production of antibodies in Escherichia coli.15 This technology paved the way for the detection of novel antibodies and offered various advantages over polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies such as production of variety of antibodies using the libraries, thus facilitate alteration of antibody affinity and specificity, and acceleration of the process of antibody generation.16 The recombination of light- and heavy-chain DNAs of an antibody by reliable cloning is the main requirement for successful generation of single-chain fragment variable (scFv) antibodies.17 In this regard, optimized phage display library was engineered for the functional synthesis of scFv.18 Various parameters such as vector stability, controlled expression, and robustness have been optimized for the generation of highly specific and affinity-rich scFvs for the major metabolites of heroin.19,20 Detection of morphine using scFv will help in the development of highly specific biosensors. The epitopic region in scFv recognizes its antigen with certain degrees of similarity and specificity.

Optical methods are gaining importance in biomedical applications due to surface plasmon resonance properties of AuNPs.21,22 The resonance properties of AuNPs generate oscillation and scattering of conductive electrons. The resonance properties depend on the size, shape, and refractive index of AuNPs. Antibodies can be functionalized and attached on the surface of AuNPs by electrostatic, hydrophobic, or direct covalent bonding. A novel reverse colorimetric immunoassay was developed for the detection of prostate-specific antigens using magnetic and gold nanoparticles.23 The major advantages of the immunoassays that provide platform for the dipstick are the rapid color development due to the antigen–antibody reaction, cost-effectiveness, and on-site application. Combination of optical properties of gold nanoparticles and antibodies as an immunoprobe on a dipstick helps to design a rapid, on-site applicable device for opiates, other contaminants, such as antibiotics24,25 and pesticides,26–29 as well as for adulteration30 and gas sensing.31 In this study, we report the development of a dipstick-based optical nanosensor for the rapid detection of morphine in spiked urine samples. For this purpose, recombinant scFv for morphine was expressed by a phage display method in Escherichia coli. Characterization of specific scFv fragments was performed by various microscopic, spectroscopic, electrophoretic, and ELISA-based techniques using a well-characterized hapten–protein conjugate (Morphine-BSA).32 The developed gold nanoparticle-based dipstick is simple, rapid, and cost effective. It takes less than 5 min to complete the analysis of opiate drugs in spiked urine samples.

Experimental

Materials

Human single-chain scFv libraries – Tomlinson I + J – were obtained from the Medical Research Council, Cambridge, UK.33 This library contained (in phagemid/scFv format – fused to the pIII minor coat protein of M13 bacteriophage) helper phage KM13 and E. coli strains TG1 and HB2151 for the selection of specific antibody clones and production of soluble single-chain Fvs, respectively. The scFv phagemid library contained synthetic V-gene (VH–VL) from lox library vector recloned into a (pHEN2) phagemid vector.34 The library size is 1.47 × 108 phagemid clones in E. coli TG1 cells with approximately 96% of clones containing inserts. The Morphine-BSA conjugate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

Tris, skimmed milk powder, Bacto-agar, tryptone, and yeast extract (TY) were procured from Hi Media Laboratories. IPTG (isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside), ampicillin, kanamycin, glucose, glycerol, NaCl, Na2HPO4, NaH2PO4·2H2O, PEG 6000, CaCl2, and Trypsin T-1426 Type XIII from Bovine Pancreas were procured from Sigma Chemical Company Ltd., Delhi, India. Maxisorp immuno test tubes were procured from Tarsons Labwares, Delhi, India. Nunc Bio-Assay dish, Nunc 24, and 96 well Maxisorp plates were procured from Nunc, Delhi, India. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A and HRP-anti-M13 were procured from Amersham Biosciences, India. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was purchased from Bangalore Genei, India, and 0.22 μm filters were purchased from MDI, India.

Panning and selection of morphine scFv clones

The stock of I + J library and helper phage KM13 was expanded to retain sufficient quantity in several rounds of the panning procedure. The library was amplified, and the phage particles were rescued by superinfection with the helper phage.35,36 The panning was conducted separately for I + J libraries to ensure the selection of most morphine binding clones.

Briefly, immunotubes were coated with Morphine-BSA (50–5 μg mL−1) and kept overnight (O/N) at 4 °C. Blocking was performed with 2% skimmed milk prepared in a phosphate buffer saline (in PBSM, pH-7.4) for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Then, 1013 phage units of the library were added together to 4 mL of 2% PBSM and incubated for 1 h at RT using a rocker and allowed to stand for further 1 h at RT. Immunotubes were washed 10 times in the first round of panning and later 20 times in subsequent panning with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. Finally, the bound phages were eluted by adding 500 μL of trypsin-PBS (50 μL of 10 mg mL−1 trypsin stock solution + 450 μL PBS) and incubated for 10 min at RT. An aliquot of eluted (250 μL) phages was used to infect a fresh exponentially growing culture of (1.75 mL) TG1 cells and incubated in a water bath without shaking at 37 °C for 30 min to allow optimal infection. Phage particles were rescued by superinfection with the helper phage, amplified, and used for further rounds of panning as per the instruction in the Tomlinson (I + J) protocol. Further, six rounds of panning were carried out for selection of morphine-specific scFv-phage clones.

Screening of morphine-specific clones by monoclonal phage ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with 100 μL/well of morphine-BSA (5 μg mL−1) in 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and kept O/N at 4 °C. Blocking was performed as described in Section 2.2. A total of 96 individual colonies (supernatant) were added from the titration plates into 96-well ELISA plates (100 μL per well) and incubated for 2 h at RT. Phage solution was discarded, and the plates were washed three times with PBST. The protein L-HRP was added (100 μL per well) at a 1 : 3000 dilution in 2% PBSM and incubated for 1 h at RT. The TMB substrate (100 μL per well) was added and incubated at RT for 20 min. Blue color was developed. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL per well of 1 M H2SO4. The blue color that developed turned into yellow. The absorbance was measured at OD450 nm (Biotek-XS Plus).

Phagemid DNA sequencing, translation, and alignment

Isolated pIT2 phagemid DNA from all seven clones was sequenced by the Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH) Facility, Chandigarh. Primers used for phagemid sequencing were LMB3 (forward primer) (5′ CAGGAA ACA GCT ATG AC3′) and pHEN (reverse primer) (CTA TGC GGC CCC ATT CA). Alignment of DNA sequences was carried out using readily available web-based tools.

Expression and purification of soluble morphine scFv antibody fragments

From each selection round, 10 μL of eluted phages were taken and infected with 200 μL of exponentially growing HB2151 nonsuppressor strain (OD600 = 0.4) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. This was followed by transfer into culture flasks containing 1000 mL TY/ampicillin/0.1% glucose and incubation at 37 °C, 250 rpm until OD900 = 0.9. At this stage, the lacZ promoter carries out the transcription of scFv cassette after induction with isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM + 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin) and incubation at 30 °C, O/N, at 200 rpm to harvest antibody fragments after secretion into culture supernatant. The induced culture was centrifuged at 30 000× g at 4 °C for 30 min, and the supernatant was obtained. The scFv fragments specific for morphine were purified using protein-L immobilized on agarose resin (according to manufacturer's Pierce instructions). The eluted positive protein fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 1× PBS, pH 7.4. Purity of morphine-positive scFv antibodies was evaluated by separation with 12% polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gels.37 The concentration of the purified scFv was determined at 280 nm using the Hitachi 2800 UV-vis spectrophotometer.

Preparation of the morphine scFv–colloidal gold immunoprobe

Monodispersed (20 nm) gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were prepared.38,39 Briefly, 0.01% tetrachloroauric acid (gold chloride) was dissolved in 50 mL of Milli-Q water. When the solution reached the boiling point, 2 mL sodium citrate solution (1%, w/v) was added rapidly and further boiled for 10 min until bright wine red color was developed. The average particle size of colloidal gold was determined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Jeol, JEM-2100) operated at 120 kV. The TEM sample was prepared by placing a drop of colloidal gold on carbon-coated copper grid, and the measurement was conducted at an operating voltage of 120 kV. The morphine scFv/AuNPs conjugate was prepared to develop an immunoprobe. For this purpose, 100 μg of antibody was added dropwise to 1 mL of AuNP solution ([Au] = 2.4 × 10−4 mol L−1) prepared in a phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 100 μg mL−1. Before adding the antibody, 10 mM dilute Na2CO3 was added to maintain the pH of the AuNP solution at 7.4. The morphine scFv/AuNP immunoprobe was incubated O/N at 4 °C and unbound antibody was removed by centrifugation at 12 000 rpm for 30 min. The pellet was washed with 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) + 2% BSA three times to remove any traces of the unbound material. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) and stored at 4 °C until use. Characterization was conducted by TEM, UV-vis spectrophotometry (Hitachi 2800), and dynamic light spectroscopy (DLS; Malvern 2.0) to confirm the size and hydrodynamic diameter of the AuNPs and scFv/AuNP immunoprobe.

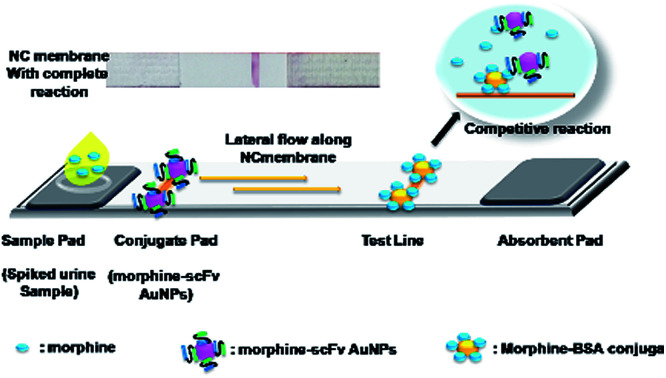

Dipstick-based optical detection of morphine

An optical immunochromatographic kit was developed using the morphine-BSA conjugate. The dipstick consists of an application pad, test line, and absorption pad, as shown in the graphical abstract. The test line was prepared on a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane (2.0 μL per line) with the morphine-BSA conjugate (2.0 mg mL−1 prepared in 3% methanol) and dispensed using an Easy Printer (Advance Microdevices, Ambala, India). Sample pads with a glass fiber were added to the morphine/scFv/AuNP immunoprobe solution (1 : 200). The assembled NC strip (sample pad, NC membrane, and absorption pad) was dried in laminar for 2 h and inserted into a plastic cassette to be used as a dipstick. Urine samples (50 μL) were spiked with heroin, MAM, morphine, and codeine in a sample well, separately. Competitive reaction of opiate drugs and scFv/AuNP immunoprobe took place instantaneously. The developed color intensity was inversely proportional to the amount of analyte present in the sample. The optical signal was measured by a gel doc system (CamiImager™ Ready, Alpha Innotech Corporation, USA) for quantification of the results.

Results and discussion

Selection and isolation of the scFv phages against morphine

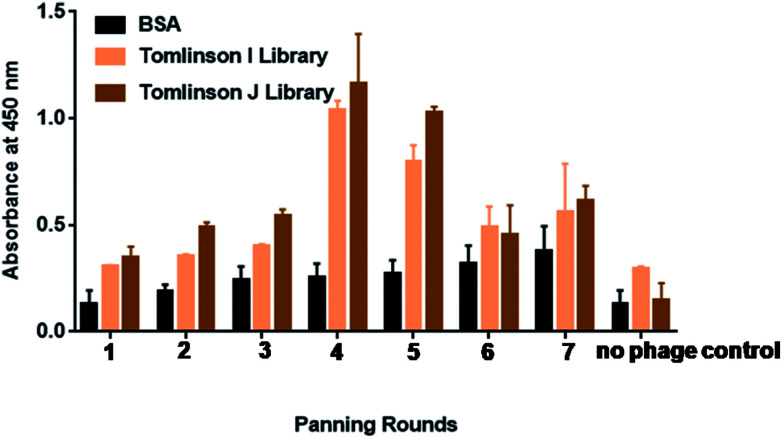

Biopanning was performed against morphine using Tomlinson (I + J) libraries for up to seven rounds, as shown in Fig. 1. Morphine-BSA was coated in the concentration range from 50 μg mL−1 to 5 μg mL−1 in successive rounds of panning. Table S1† shows the coated concentration of morphine-BSA antigen and yields of morphine-specific phages in successive rounds of panning. The yield of morphine-specific phages was very low in the first three rounds of panning with 7.3 × 10−7 pfu mL−1. Specific amplification of bacteriophage was significantly increased by more than 2-fold in the fourth and fifth panning. This is taken as a preliminary indication that effective enrichment of bacteriophages is necessary to enhance the binding capacity with morphine.40 This outcome confirmed that phage particles isolated with trypsin retained their infective properties.

Fig. 1. Binding of selected phage-scFv antibodies from 7 rounds of panning for morphine by polyclonal phage ELISA. Polyclonal phages were rescued at each round of panning against morphine. Culture supernatants containing approximately 1013 phage particles were analyzed using plaque forming unit per milliliter (pfu mL−1). Absorbance values are represented as the mean standard deviation (sd) for three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviation for each set of data. The background binding (negative control) values of the individual phage-bound scFv to the support solution (PBS) were subtracted from the total binding values, thus these data represent specific binding. Due to the fact that negative control values differed for each phage clone, they are not indicated on the figure.

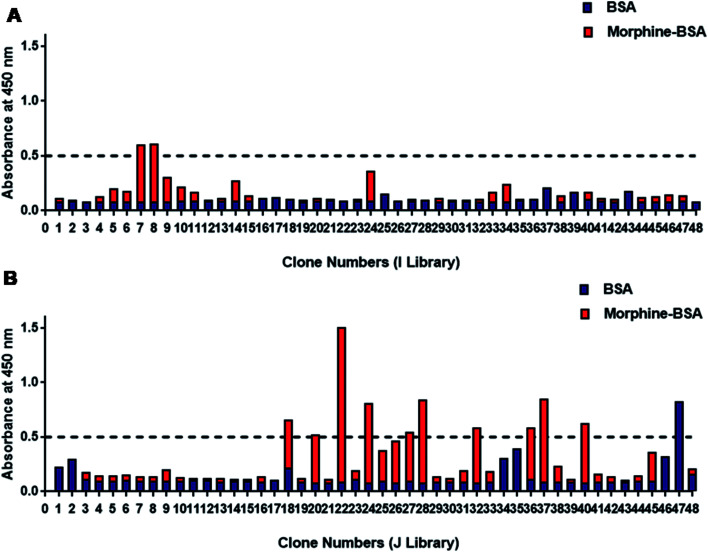

Specificity of individual scFv-phage clones measured by ELISA

Totally, 96 phage colonies were picked up randomly from TY plates for screening of morphine-positive clones (Fig. 2). Total six clones showed higher binding for morphine and were named as SP-7 and SP-8 from I library (Fig. 2A) and SP-22, 24, 28, and 37 from J library (Fig. 2B). The absorbance value of the selected clones for morphine vs. negative control was found to be above 0.5 : 0. Binding data confirmed that out of the two clones SP-22 and 37 from J library, SP-22 was highly specific for morphine (data not shown). Soluble scFvs were produced for and analyzed by monoclonal phage ELISA on immobilized morphine-BSA conjugate and BSA as a control. The ELISA analysis using soluble scFvs instead of scFv phage minimized the occurrence of false positives because some antibody fragments bound only as antibody phage particles to anti-M13-HRP. Therefore, to avoid this, we used protein-L-HRP that bound specifically to the scFv variable region only.41

Fig. 2. Binding of 96 selected phage-scFv antibodies to morphine by monoclonal phage ELISA. (A) 96 individual clone specificities to morphine are shown with Tomlinson I and (B) J library respectively. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using protein-L-HRP for the detection of bound phage-expressed scFv to morphine. Absorbance values are represented as the mean for three independent experiments. This data represent specific binding and background values (negative control) of the individual phage-bound scFv were subtracted from the total binding values.

Expression of soluble morphine-scFv

The expression of soluble scFv for morphine was in the range from 0.032 to 1 mg L−1 that was in close agreement with the yield obtained from the clones isolated from the E. coli culture using Tomlinson libraries.42 The amber stop codon between c-myc tag and gIII in the scFv clone is recognized as a stop codon, and soluble scFv fusion protein is produced as a consequence. This ensures the expression of all selected clones including those in which the scFvs contain TAG stop codons (TG1 is able to suppress termination and introduce a glutamate residue at these positions). Unfortunately, since the TAG stop codon between scFv and gIII gene is also suppressed, this leads to co-expression of scFv-pIII fusion. This tends to lower the overall levels of scFv expression, even in clones where there are no TAG stop codons in scFv itself. To circumvent this problem, the selected phage has been used to infect HB2151 (a nonsuppressor strain), which is then induced to obtain soluble expression of antibody fragments (scFv genes that do not contain TAG stop codons will now yield higher levels of soluble scFv than in TG1, but those that contain TAG stop codons will not produce any soluble scFv).43

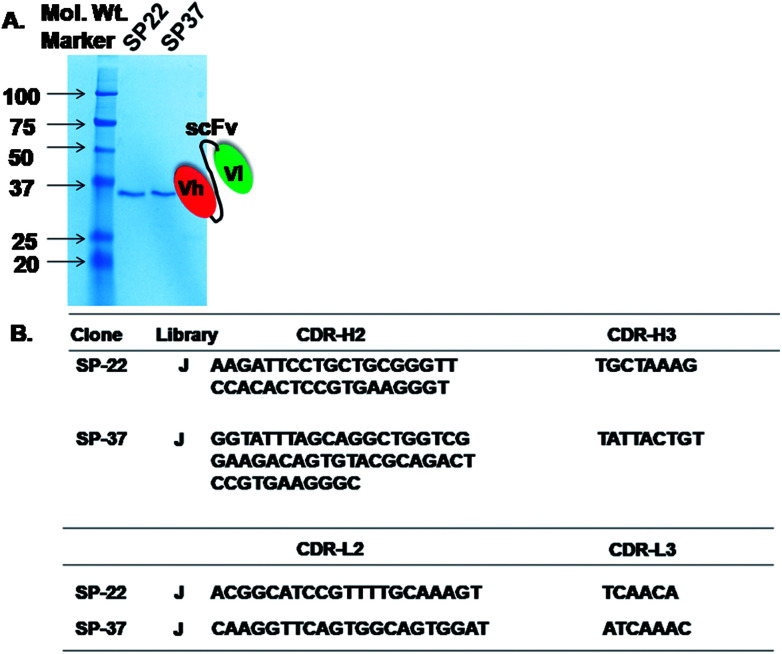

The results indicated that scFv was expressed in E. coli and showed bands corresponding approximately to 30 kDa when compared with the case of a ladder in parallel with the SP-22 and 37 from J library (Fig. 3A). These results indicated that the expression of scFv was successful in the HB2151 E. coli strain. The immunochromatographic dipstick assay was developed after successful expression and purification of morphine-specific scFv.

Fig. 3. (A) 12% SDS-PAGE analysis of purified scFvs from clones (SP-22 and SP-37) isolated from Tomlinson I and J library. The position of the bands appears to indicate that the molecular weight of the expressed scFv fragments is approximately 30–32 kDa. (B) Deduced nucleotide sequences (depiction of cdr-h (heavy) and cdr-l (light chain)) of scFv fragments with binding specificity to morphine isolated from Tomlinson I + J library.

Identification of the morphine-scFv clone by DNA sequencing

We used NCBI database to blast the obtained sequences of SP-22 and 37 from J library and confirmed that the nucleotide sequences were human VH (118 amino acids) and VL (100 amino acids). Fig. 3B shows a complete sequence of VH and VL regions of morphine scFv. On the basis of the abovementioned confirmation, a morphine-scFv antibody was used to express proteins in the HB2151 E. coli strain expressing soluble scFv.

Colloidal gold-labeled IgY: immunoprobe

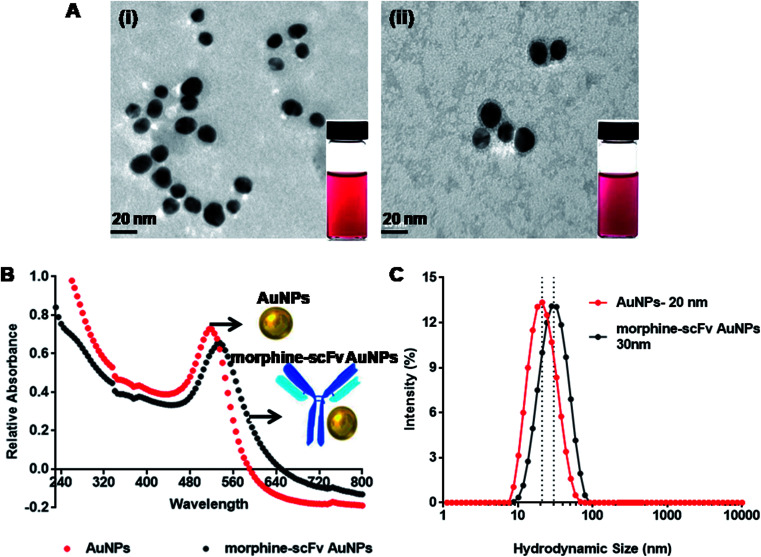

Monodispersed AuNPs were synthesized by reduction of chloroauric acid using sodium citrate by a chemical condensation method. TEM analysis (Fig. 4A-i) showed that the synthesized AuNPs were monodispersed with a median core size of 20 ± 1.95 nm. The morphine scFv antibody was adsorbed on the surface of AuNPs by electrostatic and hydrophobic interaction, also shown in TEM after negative staining (Fig. 4A-ii). The AuNPs were found to be encircled by morphine-scFv antibodies. UV-vis spectra of AuNPs (red line) and their immunoprobes (black line) are shown in Fig. 4B. The final concentration of AuNPs in morphine-scFv-AuNPs immunoprobe solution was 5.1 × 10−4 mol L−1, and the unbound antibody concentration was 0.23 μg mL−1. The surface plasmon resonance properties of the AuNPs showed a peak at ∼520 nm. The binding of morphine-scFv to AuNPs causes a red shift of 5 nm and broadens the surface plasmon band. DLS measurements were in close agreement with TEM and UV-vis spectroscopy results (Fig. 4C), and the hydrodynamic sizes of AuNPs and morphine-scFv-AuNPs were 20 and 30 nm, respectively. This size monodispersity is crucial for the development of an immunoprobe since the surface plasmon response of AuNPs is highly dependent on the size and size distribution of these NPs.44 We observed no significant change in their signal intensity before and after scFv conjugation with AuNPs.

Fig. 4. Labeling and characterization of AuNPs and morphine scFv/AuNPs/immunoprobe by (A-i) tem images of AuNPs of ∼20 nm and (A-ii) labeled AuNPs with scFv that clearly showed immobilization of the scFv antibody on the surface of AuNPs; (B) UV-vis spectroscopy also confirmed the labeling as showed from the red shift at 525 nm from 520 nm in case of AuNPs; and (C) DLS spectra showing hydrodynamic diameters of ∼20 nm with polydispersity index (pdi: 0.167) and ∼28 nm (pdi: 0.172), respectively.

Dipstick-based assay development

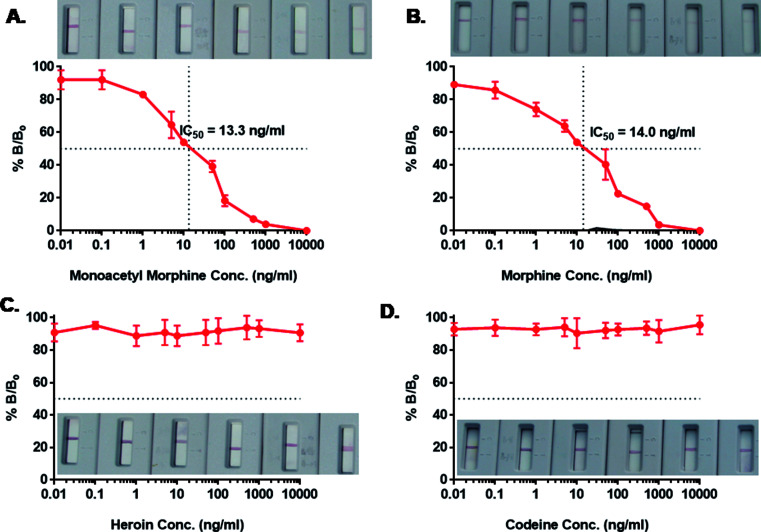

Immunochromatographic assay was developed for the detection of AuNP-labeled morphine scFv-immunoprobe. The illustration of the developed device is shown in Fig. 5. We tried an array of blocking agents (skim milk, PEG, PVP, PVA, and BSA), but they caused trailing effect on the strip due to its sticky nature and hence reduced the lateral wicking rate.45 Therefore, blocking was not performed at the time of the assay development. The detection of drugs was based on a competitive reaction between the target analyte and morphine-BSA conjugate that was coated onto the test line. A range of concentrations (1–10 000 ng mL−1) of morphine and its analogs (heroin, MAM, and codeine) was prepared in the same manner as in our previous studies for the IgY antibodies.10 The detection range was 1–1000 ng mL−1, and inhibition of tracer competitive binding (IC50) was observed around 13.3 and 14.0 ng mL−1 with a limit of detection (LOD) of 5 ng mL−1 for MAM and morphine, respectively. The IC50 value and LOD for morphine were quite similar to those of MAM; this explained the close similarity in their chemical structures with a difference only in the 3-hydroxyl group in MAM and the 3-acetyl group in the case of morphine. The isolated scFv fragments do not show any cross reactivity with heroin and codeine possibly due to their high recognition and specific binding with the selective antigen. The validation was also conducted by ELISA using the same samples (data not shown). A good correlation was observed to be 0.978 (n = 8) between ELISA and dipstick assay for morphine in spiked urine samples. The IC50 value obtained by ELISA was 4.5 ng mL−1, whereas in dipstick assay, it was 14 ng mL−1. Table 1 shows the scFv-based biosensors with their IC50 values and the limit of detection. The obtained values are in close agreement as the difference in the sensitivity can be compromised since ELISA is time consuming and requires a trained person for analysis. Therefore, scFv-based diagnosis of morphine using a dipstick kit can be used for rapid, highly selective, and on-site detection in urine, blood, and saliva samples.

Fig. 5. Competition ELISA determined binding properties of morphine recognizing soluble and purified scFv fragment synthesized from selected clone isolated from Tomlinson I library. Nitrocellulose membrane was coated with morphine-BSA as test line (2 mg mL−1) in 3% methanol. The morphine/scFv/AuNPs immunoprobe (1 : 200) was absorbed on to glass fiber lining, followed by addition of spiked morphine (B) in urine sample well. Cross reactivity studies were performed in heroin (C), MAM (A), codeine (D), where scFv did not showed any binding with heroin and codeine. The data represents mean ± standard deviation from duplicate measurements.

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity of various morphine-specific scFv-based biosensors.

| Name of drugs | Type of sensor | IC50 | Limit of detection (LOD) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papavarine | Lateral-flow immunochromatographic assay | — | 5 ng mL−1 | 46 |

| Morphine | Paper-based lateral flow assay | — | 1 ng mL−1 | 47 |

| Opium, morphine, codeine, and heroin | Surface plasmon resonance-based (SPR) | 257 ng mL−1, 36.4, 7.3, and 7.4 nM | — | 48 |

| Morphine | Surface plasmon resonance-based (SPR) | 100 ng mL−1 | 6 ng mL−1 | 49 |

| Morphine-3-glucuronide | Surface plasmon resonance-based (SPR) | 30 ng mL−1 | 9.7 ng mL−1 | 50 |

| MAM, morphine | Gold nanoparticles-based dipstick | 14 ng mL−1 | 5 ng mL−1 | Present work |

Conclusions

In this study, we have successfully performed the screening and isolation of morphine-specific scFv clones from Tomlinson I + J libraries. The developed recombinant antibodies bind very specifically to morphine, and MAM. ELISA-based results indicate that morphine-specific scFv antibodies have the potential to be used as a molecular affinity interface receptor and can be used as a tool for the development of biosensor devices. An optical, fast, and field-applicable dipstick immunosensor kit was developed for morphine detection with a limit of detection up to 5 ng mL−1 in spiked urine samples. The developed AuNP/morphine scFv device is quite comparable (5 ng mL−1) with our already established colloidal gold-based morphine IgY (2.45 ng mL−1) for opiate drugs. The main advantage of the new scFv strip test is that it is highly specific due to epitope recognition (recognizes a single change in amino acid residues), whereas our polyclonal anti-morphine IgY antibodies recognize heroin and its metabolites with similar specificity and sensitivity. The scFv immunochromatographic test kit is highly specific and recognizes morphine and MAM, whereas the IgY-based kit for morphine recognizes all major metabolites of heroin with similar sensitivity and specificity. The shelf-life of the developed device is higher, and it is stable at room temperature for up to 4 weeks without any significant loss of activity. Therefore, the developed device can detect the presence of drug in less than 5 min and can be used for on-site field monitoring of morphine and its analogs.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the funding support provided by the Central Forensic Science Laboratory (CFSL), Chandigarh, India and ECR/000075, Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi, India.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Table S1 for enrichment of morphine-specific single-chain fragment variable antibodies. See DOI: 10.1039/c7ra12810j

References

- Jones J. M. Raleighb M. D. Pentelb P. R. Harmond T. M. Keylera D. E. Remmele R. P. Birnbauma A. K. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013;74:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken L. G. Masman A. D. de Winter B. C. M. Koch B. C. P. Baar F. P. M. Tibboel D. van Gelder T. Mathot R. A. A. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:697–709. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lull M. E. Freeman W. M. VanGuilder H. D. Vrana K. E. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Huynh K. Barhate R. Liu J. Tam P. Rodrigues W. Coulter C. Moore C. Soares J. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2015;39:726–733. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkv090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. L. Ye X. X. Li Y. S. Tan Z. F. Jiang J. Z. Anal. Lett. 2016;49:1303–1309. doi: 10.1080/00032719.2015.1101603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa S. Zourob M. Microchim. Acta. 2017;184:2281–2289. doi: 10.1007/s00604-017-2261-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ensafi A. A. Abarghoui M. M. Rezaei B. Sens. Actuators, B. 2015;219:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ya Y. Xiaoshu W. Qing D. Lin J. Yifeng T. Anal. Methods. 2015;7:4502–4507. doi: 10.1039/C5AY00764J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. Han Y. Lin L. Deng N. Chen B. Liu Y. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:1290–1295. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S. Caplash N. Sharma P. Suri C. R. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009;25:502–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S. Tey J. N. Wijaya I. P. M. Palaniappan A. I. Wei J. Rodriguez I. Suri C. R. Mhaisalkar S. G. Small. 2010;6:993–998. doi: 10.1002/smll.200902139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S. Suman P. Kumar A. Sharma P. Capalash N. Suri C. R. BioImpacts. 2015;5:207–213. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei X. Zhang B. Tang J. Liu B. Lai W. Tang D. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;758:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu J. Tang D. Chem.–Asian J. 2017;21:2780–2789. doi: 10.1002/asia.201701229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano G. L. Ceccarelli E. A. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D. Hu S. Wan W. Xu M. Du R. Zhao W. Gao X. Liu J. Liu H. Hong J. PLoS One. 2015;10:e-0129125–e-0129141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland L. K. Norris N. A. Marquardt H. Tsu T. T. Hayden M. S. Neubauer M. G. Yelton D. E. Mittler R. S. Ledbetter J. A. Tissue Antigens. 1996;47:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebber A. Bornhauser S. Burmester J. Honneger A. Willuda J. Bosshard H. R. Pluckthun A. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;201:35–55. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(96)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon P. P. Manning B. M. Daly S. J. Killard A. J. O'Kennedy R. J. Immunol. Methods. 2003;276:151–161. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam A. Borgen T. Stacy J. Kausmally L. Simonsen B. Marvik O. J. Brekke O. H. Braunagel M. J. Immunol. Methods. 2003;280:139–155. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D. Cuia Y. Chen G. Analyst. 2013;138:981–990. doi: 10.1039/C2AN36500F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. Ye H. Tang D. Tao J. Habibi S. Minerick A. Tang D. Xia X. Nano Lett. 2017;17:5572–5579. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b02385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. Xu M. Hou L. Chen G. Tang D. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:6945–6952. doi: 10.1021/ac401433p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. Liu L. Song S. Cui G. Zheng Q. Kuang H. Xu C. Food Agric. Immunol. 2017;28:625–638. doi: 10.1080/09540105.2017.1309358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. Liu L. Xu L. Song S. Kuang H. Cui G. Xu C. Nano Res. 2017;10:108–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-016-1270-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L. Liu L. Song S. Kuang H. Xu C. Food Agric. Immunol. 2017;28:639–651. doi: 10.1080/09540105.2017.1309359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suri C. R. Boro R. Nangia Y. Gandhi S. Sharma P. Wangoo N. Rajesh K. Shekhawat G. S. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2009;28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2008.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suri C. R. Kaur J. Gandhi S. Shekhawat G. S. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:235502. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/23/235502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya I. P. M. Nie T. J. Gandhi S. Boro R. Palaniappan A. Hau G. W. Rodriguez I. Suri C. R. Mhaisalkar S. G. Lab Chip. 2010;10:634–638. doi: 10.1039/B918566F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Liu L. Xu L. Song S. Kuang H. Cui G. Xu C. Nano Res. 2017;10:2833–2844. doi: 10.1007/s12274-017-1490-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. Tang D. Tang D. Niessner R. Knopp D. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:10153–10160. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S. Sharma P. Capalash N. Verma R. S. Suri C. R. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:215–222. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbarnia L. Farajnia S. Babaei H. Majidi J. Akbari B. Khosroshahi S. A. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016;6:563–571. doi: 10.15171/apb.2016.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A. D. Williams S. C. Hartley O. Tomlinson I. M. Waterhouse P. Crosbyl W. L. Kontermann R. E. Jones P. T. Low N. L. Allison T. J. Prospero T. D. Hoogenboom H. R. Nissim A. Coxl P. L. J. Harrison J. L. Zaccolo M. Gherardi E. Winter G. EMBO J. 1994;13:3245–3260. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huovinen T. Syrjänpää M. Sanmark H. Seppä T. Akter S. Khan L. M. F. Lamminmäki U. BMC Res. Notes. 2014;7:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R. A. Cox F. van der Horst M. van den Oudenrijn S. Res P. C. M. Logtenberg T. de Kruif J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkilany A. M. Yaseen A. I. B. Kailani M. H. J. Nanomater. 2015;16:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Young J. K. Lewinski N. A. Langsner R. J. Kennedy L. C. Satyanarayan A. Nammalvar V. Lin A. Y. Drezek R. A. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavan B. Dalpiaz A. Ciliberti N. Biondi C. Manfredini S. Vertuani S. Molecules. 2008;13:1035–1065. doi: 10.3390/molecules13051035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhrif Z. Pugnière M. Henriquet C. di Tommaso A. Dimier-Poisson I. Billiald P. Juste M. P. Aubrey N. mAbs. 2016;8:379–388. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1116657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eteshola E. J. Immunol. Methods. 2010;358:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. Ke A. Doudna J. A. J. Immunol. Methods. 2007;318:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. H. Huang S. Brownlow W. Salaita K. Jeffers R. B. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:15543–15551. doi: 10.1021/jp048124b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J. Singh K. V. Boro R. Thampi K. R. Raje M. Varshney G. C. Suri C. R. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:5028–5036. doi: 10.1021/es070194j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W. Suryoprabowo S. Zheng Q. Kuang H. Food Agric. Immunol. 2017;28:1304–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Teerinen T. Lappalainen T. Erho T. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014;406:5955–5965. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukizono M. Kamegawa M. Tanaka K. Kohra S. Arizono K. Hamazoe Y. Sugimura K. Antibodies. 2013;2:93–112. doi: 10.3390/antib2010093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J. Dillon P. P. O'Kennedy R. J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2003;786:327–342. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend S. Finlay W. J. Hearty S. O'Kennedy R. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006;22:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.