Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) gene therapy has the potential to transform the lives of patients with certain genetic disorders by increasing or restoring function to affected tissues. Following the initial establishment of transgene expression, it is unknown how long the therapeutic effect will last, although animal and emerging human data show that expression can be maintained for more than 10 years. The durability of therapeutic response is key to long-term treatment success, especially since immune responses to rAAV vectors may prevent re-dosing with the same therapy. This review explores the non-immunological and immunological processes that may limit or improve durability and the strategies that can be used to increase the duration of the therapeutic effect.

Keywords: animals, gene expression, gene expression regulation, gene therapy, genetic therapy/methods, gene transfer techniques, genetic vectors, human genetics, transgenes

Durable transgene expression following rAAV gene therapy is key to long-term treatment success; however, it is currently unknown how long the therapeutic effect will last. In this review, Gao and colleagues explore non-immunological and immunological factors that may affect durability, and strategies to potentially optimize the duration of therapeutic effect.

Introduction

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) gene therapy offers the potential for long-term amelioration of a number of monogenic genetic disorders following only a single treatment. The success of such treatments depends not only on the magnitude of therapeutic effect but also on the duration. The longevity of the therapeutic effect is dependent on the maintenance of transgene expression over the long term.

Evidence is emerging that the effects of rAAV gene therapy can be maintained over long periods of time. Behavioral recovery in a monkey Parkinson’s disease model was demonstrated 15 years after administration of an rAAV-based gene therapy to the putamen.1 In humans, stable therapeutic expression of factor IX (FIX) in people with severe hemophilia B has been observed over a period of 8 years following the systemic administration of an rAAV8-based vector, as of 2018.2 In addition, FIX expression has been detected in human muscle tissue following muscle-directed gene therapy up to 10 years post-administration.3 In the first two rAAV approved human gene therapies—alipogene tiparvovec for the treatment of familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency and voretigene neparvovec for the treatment of Leber’s congenital amaurosis—durability of response up to 6 and 4 years has been reported in publications from 2016 to 2009, respectively.4, 5, 6 It is important to note that the timescales mentioned here do not represent the limits of treatment durability, but rather what has been observed and published to date. In its 2019 review of voretigene neparvovec, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) noted the existence of data showing sustained therapeutic effects up to 7.5 years, although this has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.7

However, loss of previously established transgene expression has also been reported in both animals and humans.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 From these studies, it appears that the durability of transgene expression following rAAV gene therapy is complex and multifactorial, although the timing of loss of expression may provide important clues as to the cause (Figure 1).

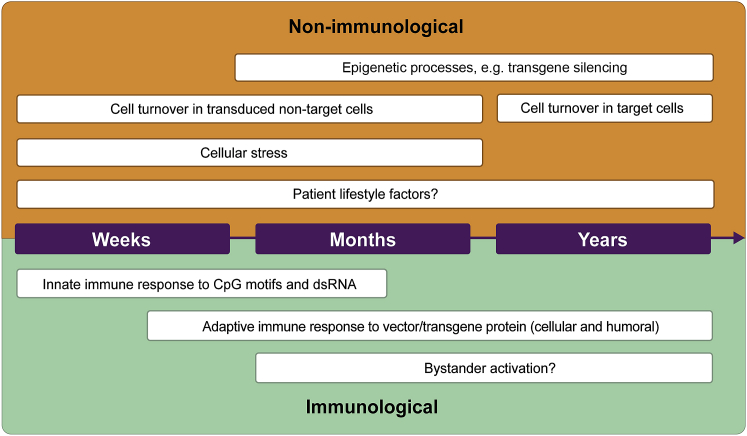

Figure 1.

Factors that may reduce durability

Non-immunological (orange) and immunological factors (green) that may affect durability over weeks, months, and years post-gene therapy administration. CpG, 5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA.

As more gene therapies enter the clinic, confidence in the durability of effect is of paramount importance to all stakeholders, including patients and their families/caregivers, physicians, researchers, industry, as well as payers and regulatory bodies, and will be key to deciding the value that each group of stakeholders attaches to gene therapies. For these reasons, it is important that the factors underlying durability are elucidated, so that therapies and long-term follow-up of patients can be optimized to provide durable transgene expression.

This review explores key concepts relating to the durability of transgene expression after it has been successfully established, outlining what we can observe from existing research and post-marketing data and what remains unknown. Starting with a brief review of rAAV vector design and biology, non-immunological and immunological factors that may affect the durability of transgene expression and approaches to address them are then considered in turn. Both animal and human data are included, although it should be noted that the degree to which animal model data can be extrapolated to human gene therapy remains uncertain, especially when considering immunological responses to rAAV from prior exposure to the wild-type virus. Each concept is discussed individually, and due to the remaining need for further research to fully elucidate the role of each factor and the possible complexities from interplay between these factors, we do not rank the concepts in terms of their importance in supporting the durability of transgene expression.

Overview of rAAV vector design and transduction biology

AAV, a parvovirus that is dependent on co-infection with other viruses to replicate, is one of the most investigated in vivo gene therapy delivery vehicles to date.13 However, since the first in-human application in 1995,14,15 there is still only a limited timescale for assessing transgene durability in humans. rAAV, which is 25 nm in diameter16 and lacks protein-coding viral DNA (rep and cap genes) of wild-type AAV, is a protein-based nanoparticle that can traverse the cell membrane and deliver the transgene DNA it carries into the nucleus of cells.13 rAAV vectors can be engineered to alter their tissue tropism and to evade host immunity, thereby enabling more efficient transduction of the intended target tissue and successful establishment of transgene expression.17

AAV is predominantly non-integrating, unlike other viral vector platforms, such as lentivirus.18,19 Persistence of therapeutic effect after treatment is dependent on the formation and maintenance of circular episomes in non-dividing cells.13,20 While the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) that characteristically flank the AAV genome clearly function as origins of DNA replication, as well as packaging signals in rAAV producer cells, their role in episomal persistence is not well characterized. The ITRs serve as primers for second-strand synthesis in recipient cell nuclei, and then are targets for DNA repair factors that either join them together to form a circle, or join them to other linear rAAV genomes to form concatemers, or to preexisting chromosomal double-strand (ds) breaks, leading to relatively rare integration events.21,22 While the ITR hairpin structures do appear to influence which DNA repair factors are needed to form circles, it is not clear that the process is more efficient, or leads to greater durability, than simple dsDNA ends.23,24

In tissues with low cellular turnover, episomal DNA may persist for many years, as evidenced by long-term transgene expression observed in animal and human studies.2,25,26 Figure 2 outlines the essential steps following the administration of rAAV gene therapy that must be achieved to establish transgene expression. For the remainder of this review, the focus is on the factors that affect durability after successful expression has been established.

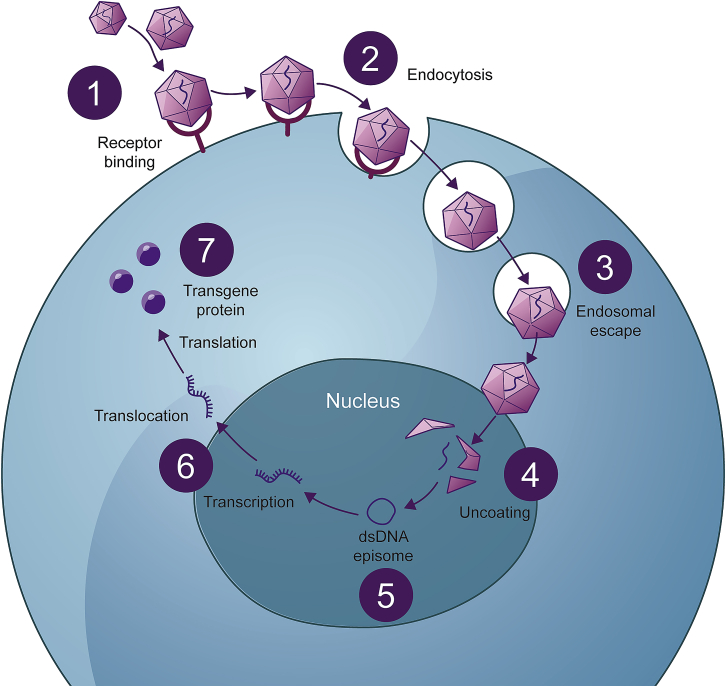

Figure 2.

From rAAV administration to long-term transgene expression

The rAAV vector binds to receptors on the target cell surface (1) and is taken into the cell by endocytosis (2). rAAV traffics from early to late endosomes (3) and is delivered to the nucleus. Once inside the nucleus, the capsid is removed (uncoating) (4), releasing the genetic material. The transgene, if single-stranded, undergoes second-strand synthesis before forming a double-stranded DNA episome (5), which is maintained in the nucleus of the cell where it can be expressed (6), resulting in the production of the protein of interest (7).

Non-immunological factors that may affect the durability of transgene expression

Several non-immunological parameters may affect the durability of rAAV-delivered transgene expression over the long term. Interplay between certain non-immunological and immunological factors is possible. For example, promoter choice, rAAV serotype, transgene characteristics, and route of administration may result in immune activation upon rAAV administration. This review explores each factor individually and does not examine the interplay in detail. We now focus on what we consider to be the relevant factors, highlighting key animal and human data for each.

Target cell population

At present, rAAV gene therapies are limited to targeting cells that are long-lived. Redosing through systemic delivery is not currently an option because of the host immune response to the initial therapy,27, 28, 29, 30 and therefore establishing durable transgene expression is of great importance. Different cell populations have differential rates of cell turnover (Table 1). Since episomes are not thought to be inherited by daughter cells and are likely to be lost during mitosis, the rate of cell turnover will determine the durability of transgene expression in the target tissue.

Table 1.

Human cell turnover of select cell types in various organ systems

| Organ system | Cell type | Mean lifespan in humans | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Hepatocytes | 200–300 daysa | 31 |

| Nervous system | Neurons | Lifetime—no replicative aging—in the absence of pathology, lifespan is only limited by lifespan of individual | 32,33 |

| Nervous system | Glial cells | 55 y | 34 |

| Skeletal muscle | Myocytes | 15.1 y | 33 |

| Eye | Lens | Lifetime: new cells are added to the outside of the lens as it grows, but cells in the lens nucleus are the same cells that were present at birth | 35 |

Several attempts have been made to measure the cell cycle of human hepatocytes, but no complete analysis exists and, therefore, it is hard to draw firm conclusions about the lifespan of human liver cells. Furthermore, the liver is made up of multiple different cell types, which are likely to have different lifespans. Existing data for liver-directed rAAV therapies show a durability far in excess of this commonly reported lifespan for human hepatocytes, indicating that either the lifespan of some transduced cells exceeds this figure or that episomes are maintained through some unknown mechanism at a sufficient rate to support ongoing therapeutic effect.

The rate of cell turnover may also vary depending on age. For example, as the liver grows in human children, cells turnover at a much higher rate than in adulthood.34,36,37 There is no known mechanism by which daughter cells inherit rAAV episomes, although this may happen under certain conditions. The episome may, by chance, segregate with one of the daughter nuclei and be maintained there until the next cell division. Alternatively, because many hepatocytes are either polyploid or multinucleated, they may undergo multiple modes of cell division during development or regeneration.38 Thus, a multinucleated cell carrying an rAAV episome in one nucleus could divide without entry into S phase, and pass the episome to a daughter cell more efficiently. Similarly, hepatocytes can undergo S phase without entry into M phase, potentially allowing the episome to remain associated with the nucleus, meaning that the durability of therapeutic effect would not be limited to one lifespan.38 Trials in children are planned and will provide insights into the degree and rate of episomal loss in pediatric livers, and therefore durability, following liver-directed rAAV gene therapy.39

Myofibers turn over slowly, and children have been included in studies for muscle-directed therapies. In humans, muscle-directed rAAV therapy for α-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency has thus far demonstrated stable transgene expression at 5 years after vector dosing.40 Neurons also have a very low rate of turnover, which should support long-lived durability of neuron-targeted rAAV treatments such as onasemnogene abeparvovec for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. According to a 2021 publication, onasemnogene abeparvovec has demonstrated a durability of up to 5.6 years after dosing.41

It should be noted that even though rAAV can be engineered to more specifically target particular tissues, tropism is not completely selective and there will be transduction of non-target tissues, which may result in transgene expression. The use of tissue- and cell-type-specific promoters can help to restrict expression to the tissue and cell population of interest;13 however, this will not completely prevent expression in non-targeted tissues.

Genome integration

Since rAAV-delivered transgenes exist predominantly as non-integrating episomes, with random integration events observed at varying frequencies,19,42, 43, 44 it is likely that the episomes will be diluted over time as cells undergo repeated rounds of replication. This could lead to reduced transgene expression and levels of the protein of interest, and this process will be accelerated in tissues with a high rate of cellular turnover. Although the non-integrating nature of AAV is generally thought of as a safety advantage, the application of rAAV-based therapy is currently limited to long-lived cells, whereas it is hypothesized that a degree of integration may allow more durable expression in tissues with a higher rate of cell turnover.

In cell culture, wild-type AAV has been shown to preferentially integrate into a locus on human chromosome 19, or similar sites bearing Rep binding elements.45,46 The integration of rAAV vector genomes has been noted in animal studies, but it is not targeted to a specific locus.47 In a 10-year follow-up of dogs with hemophilia A, evidence of rAAV integration has been observed. Interestingly, these changes were associated with increased levels of protein expression, indicating that a degree of integration may have a durability benefit. No evidence of malignancy has been found in any of the dogs and similar findings have not been reported in humans to date.26 Naturally, integration and the potential for insertional mutagenesis remain areas for continued study and vigilance in clinical research.

Transgene silencing: promoter shutoff and epigenetic processes

Promoters vary in their ability to maintain long-term transgene expression in certain cell populations, and promoter shutoff is associated with a decline in transgene expression.48, 49, 50 There is a tendency for some promoters to turn off in cells in which they are not normally active.51 For example, the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter used in some rAAV vectors is prone to shutoff in the liver within 5 weeks of administration.52 The same phenomenon has also been seen in the central nervous system, where initially the CMV promoter delivers high levels of neural expression that is silenced by 10 weeks in the murine spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia.53 Several studies have shown that the inclusion of neuron-specific promoters results in more efficient brain transduction compared with vectors carrying a CMV promoter.48,50,54,55

DNA methylation is one of the major epigenetic regulatory systems that modulates gene expression.56 In mammals, 5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′ (CpG) dinucleotide hypermethylation of promoters is associated with the inactivation of gene expression and has been identified as a mark of transgene silencing after murine leukemia viral vector transduction.57,58 However, the evidence for a role of DNA methylation leading to promoter shutoff is less clear-cut in rAAV gene therapy. In a study of muscle-directed rAAV in non-human primates (NHPs), there was no evidence of promoter methylation, suggesting that the reduction in protein expression observed was not due to methylation of the rAAV genome.59 The role of DNA methylation in rAAV transgene expression, and whether methylation would vary depending on the target tissue, remains to be determined.

Cellular stress

rAAV vectors are the most commonly studied approach in the development of in vivo gene therapies for lysosomal storage diseases with neurological involvement, as they efficiently transduce dividing and non-dividing cells in the CNS. The transgene product, in this case lysosomal enzymes, may be overexpressed following gene therapy. Animal evidence suggests that there is a limit to the degree of overexpression that can be tolerated.60 Monkeys receiving direct intracranial injections of an rAAV vector encoding β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (Hex) developed neurological symptoms in a dose-dependent manner. Histological examination of the brain tissue showed cellular loss with a dramatic increase in Hex activity measured in the thalamus.60 None of the animals had developed antibodies against Hex, suggesting a non-immune cause of the neurological damage.60 The possible mechanisms for this cellular loss include overwhelming protein trafficking pathways, the unfolded protein response, and improper glycosylation.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the site of folding of secreted and membrane proteins in eukaryotic cells. Incorrectly folded proteins are retained in the ER until they are stabilized, and irreparably misfolded proteins are targeted for proteasomal degradation.61,62 Overexpression of the transgene could overwhelm the ER quality control system, leading to the buildup of misfolded proteins, and result in ER stress. ER stress can trigger the unfolded protein response, a cascade that includes a reduction in protein translation, and may lead to the death of transduced cells.61,62

High levels of expression of factor VIII (FVIII) protein may prompt an unfolded protein response in hepatocytes. This phenomenon is not observed following the administration of a null vector or a vector expressing FIX in mice, suggesting that FVIII levels are the cause of the response.63 It is possible that the ectopic production of FVIII by hepatocytes, rather than liver sinusoid endothelial cells, could drive this response that may lead to the cessation of cellular translation and apoptosis, and ultimately a decrease in transgene expression.

Approaches to addressing non-immunological considerations for durability

As non-immunological factors that influence the durability of gene therapy become better understood, the techniques to improve durability are being explored. These approaches are still under investigation and, therefore, data supporting their use in humans are limited.

Optimizing promoter selection

By selecting promoters that limit expression to the target cell as far as is possible, inflammatory responses that may lead to the elimination of transduced cells in target tissues may be avoided. Optimizing promoter selection can also reduce the likelihood of promoter shutoff in the target organ and provide stable and efficient activity in the target tissues.55,64,65 Shortened promoter sequences have also been used successfully to restrict expression to target cells within the mammalian CNS.66,67

Using recombinases to restrict gene expression to target tissues

Intronic recombinase sites enabling combinatorial targeting (INTRSECT) uses vectors containing engineered introns to enable expression that is conditional on the presence of multiple recombinases to target gene expression to specific cell populations.68,69

Scaffold/matrix attachment region

Since rAAV vectors do not possess integrase activity, the application of rAAV gene therapy in diseases that require long-term treatment is limited to terminally differentiated tissues. To overcome this restriction, rAAV genomes can be equipped with scaffold/matrix attachment regions, which enable episomal replication and thereby achieve the maintenance of transgene expression in proliferating cells.70

Targeted genomic integration

Transgene persistence can be enhanced using a programmable nuclease to integrate the DNA into the target genomic locus. Following this, the homology-directed repair pathway of the host cell can use the rAAV genome as a donor template, leading to the heritable insertion of the therapeutic gene cassette into the host genome.71, 72, 73

Another strategy under investigation (GeneRide) uses an rAAV vector to deliver a corrective transgene that is capable of integration without the need for promoters or nucleases. The transgene is flanked by homologous strands of DNA that are recognized by the DNA repair machinery of the cell, allowing integration at a specific site in the host genome.74,75

A similar approach reported by Smith et al. uses a gene editing platform based on a class of hematopoietic stem cell-derived Clade F AAV, in which genome editing is guided by homology arms without the need for nuclease-dependent DNA breaks. Successful gene editing has been demonstrated in human cells in vitro and in vivo in mice.76

Immunologic factors that may affect the durability of transgene expression

Despite its low immunogenicity, immune responses to rAAV can occur at multiple stages following administration and have been shown to affect both the success of initial transduction and long-term durability of transgene expression.77, 78, 79, 80 In addition to an immune response to the rAAV capsid, it is possible that the expression of a therapeutic protein in an individual who does not produce the wild-type protein can result in the identification of the protein as foreign and elicit an immune response.78 An immune response to the rAAV vector or transgene product involves a complex series of interactions between the innate and adaptive immune systems (Figure 3).77,78

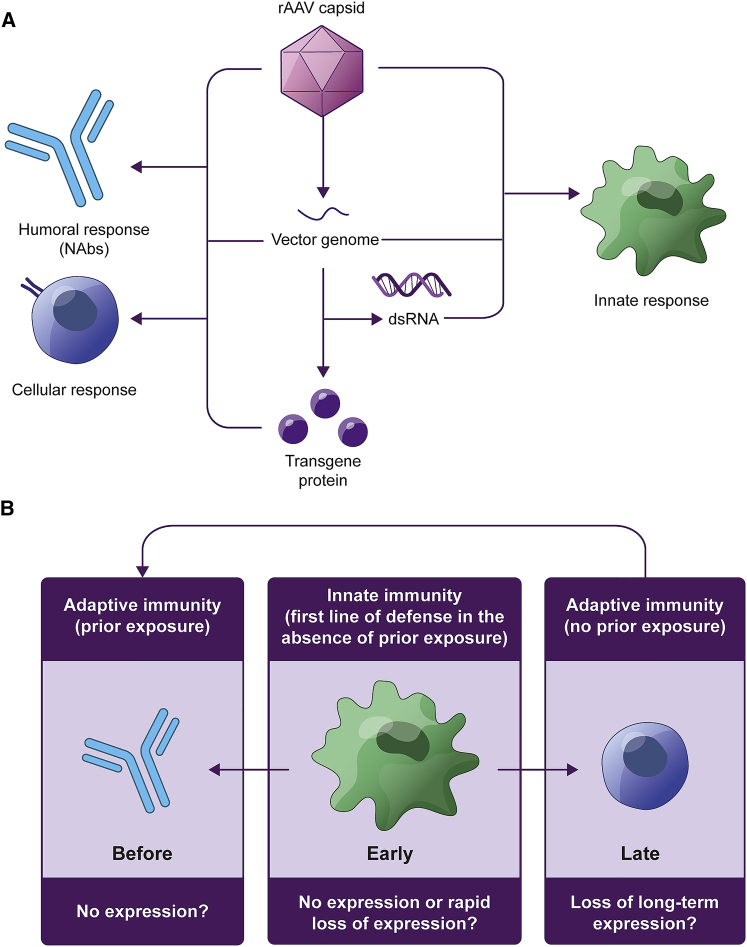

Figure 3.

Immune processes affecting the durability of rAAV gene therapy

(A) Immune responses can occur against the rAAV capsid, transgene, or transgene protein. (B) In the case of recipients with prior exposure to rAAV or a similar serotype, NAbs may prevent initial transduction, resulting in low or absent expression of the transgene. Innate immune responses could result in no expression or a rapid loss of expression, but they are more likely to provide important signals to the adaptive immune system, with the potential to reduce or eliminate expression at a later stage after transgene expression has been established. On subsequent exposure, memory cells of the adaptive immune system can respond rapidly, with the release of NAbs against the rAAV capsid. dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; NAbs, neutralizing antibodies; rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus.

Since the role of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in the potential prevention of initial transduction following the systemic delivery of rAAV has been well documented and reviewed elsewhere,30,78,81, 82, 83 and NAbs affect initial success rather than durability, they are out of the scope of this review. Of relevance to durability, if transgene expression is lost, then it is predicted that immune memory, particularly the presence of these highly specific NAbs, will prohibit systemic re-dosing with the same or a similar rAAV vector.83 However, it is worth acknowledging that most but not all current rAAV gene therapy trials (NCT03520712, NCT03569891) exclude AAV seropositive participants.84 It will be interesting to see whether successful transgene expression will be maintained over the long term in participants who had NAbs to AAV before rAAV gene therapy administration, or whether the interplay between NAbs and other aspects of the immune system may play a later role in limiting the durability of expression in these individuals.

Innate immune response to rAAV and the potential impact on durability

In the absence of prior exposure to AAV, the innate immune system is the first line of defense against rAAV and can react to both the capsid and genome (Figure 4).77,78,82 Although the innate immune response against rAAV gene therapy is considered to be mild and transient compared with other viral vectors,85 it is understood that the innate immune system plays a key role in determining the extent of a subsequent adaptive immune response,77 thus having the potential to affect the long-term durability of rAAV transgene expression. In particular, mouse studies suggest that the Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)/myeloid differentiation factor 88 pathway is critical for priming the CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response to the rAAV capsid and the transgene product.86,87 Unlike that in wild-type mice, administration of an immunogenic AAVrh32.33 capsid to the skeletal muscle of TLR9-deficient mice did not result in an interferon (IFN)-γ mediated CTL response. Furthermore, CpG depletion of AAVrh32.33 allowed evasion of the immune system and persistent transgene expression in wild-type mice.86 More recent mouse studies have shown that CpG depletion from an AAV1/2 expression cassette reduces the cross-priming of capsid-specific CD8+ T cells in mice, potentially reducing, but not completely inhibiting, T cell responses against the viral capsid and the therapeutic transgene.88

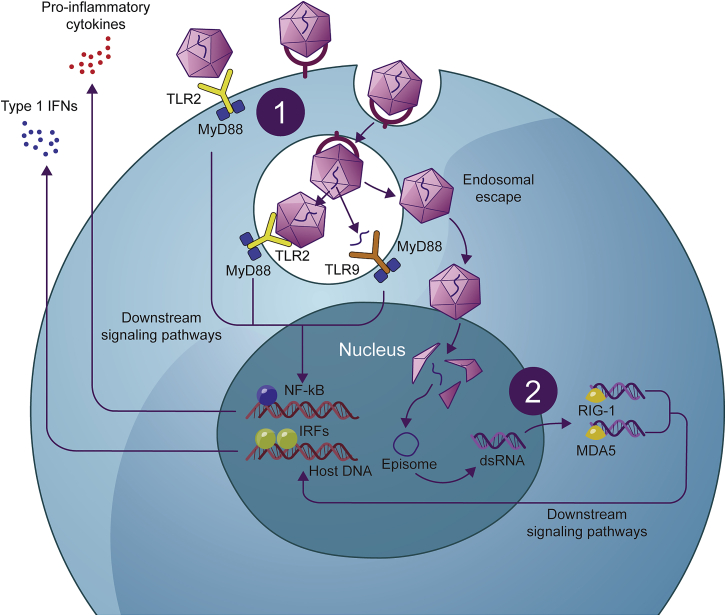

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of rAAV detection by the innate immune response

(1) TLRs are membrane-bound pattern-recognition receptors responsible for detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns, for example, in the genomes of bacteria and viruses. The rAAV genome, particularly unmethylated CpG motifs, can be detected by TLR9 on the endosomal membranes of dendritic cells following endocytosis and degradation by the endosome. In addition, TLR2, which recognizes microbial protein and glycolipid structures on the dendritic cell surface and within endosomes, has been shown to detect the AAV capsid in circulation.77,82 TLR2 and TLR9, with the downstream mediator MyD88 are believed to be the key pattern-recognition receptors responsible for initiating an innate immune response against rAAV-mediated gene therapy, triggering the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs via downstream signaling pathways involving the transcription factors nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and interferon (IFN) regulatory factor (IRF), respectively.77,82 (2) Following successful transduction, dsRNA can form and be detected by cytosolic RNA sensors, RIG-1 and MDA5, leading to the expression of IFN-β via downstream signaling pathways.77 In addition to triggering the destruction of the cell, these mechanisms led to an antiviral state in the surrounding tissue and the recruitment of innate immune cells, as well as providing activation signals for an adaptive immune response.77,78

In two hemophilia B clinical trials, codon optimization of the transgene resulted in the introduction of CpG motifs into the open reading frame of the rAAV gene therapy candidates BAX 3359 and DTX101.89 Within 3 months, FIX activity was diminished, suggesting that the loss of transgene expression may be due to the recognition of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides by TLR9 and subsequent destruction of transduced cells.9,89, 90 In the phase I/II BAX 335 trial, one participant achieved long-term transgene expression, likely due to a mutation within the interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) gene, making this participant less susceptible to innate immune signaling via IL-6.9 rAAV vectors with naturally occurring CpGs removed have demonstrated durable expression, with no or manageable CTL responses.86

Complement system

In addition to the role of pattern recognition receptors in the innate immune response, the complement system is responsible for recognizing molecular components of microorganisms via inactive proenzymes in serum. The resulting signaling cascade leads to the formation of a membrane attack complex on the surface of the pathogen or pathogen-infected cell, marking the pathogen for removal by phagocytes, as well as the lysis of target cells and the release of inflammatory mediators by leukocytes.77,80 This critical link between the innate and adaptive immune system serves as a co-stimulatory signal to increase the magnitude of an antibody response, as well as maintaining T cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation.77,91 Although the interaction between the rAAV vector and the complement system is not fully understood, it is believed to be primarily antibody driven (via the classical pathway);92 however, the exact immunoglobulins involved in this response are still under investigation. It is possible that potentially high doses of rAAV vector and choice of capsid may be involved in complement activation. For more detail, see the recent review by Muhuri et al.77

It has been generally believed that the complement system does not play a significant role in the immune response to rAAV-mediated gene therapy.77 However, complement activation has been implicated in adverse events in the clinical trials of rAAV9-mediated gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD; NCT0336250293 and NCT0336874294), as well as in immune mechanisms contributing to thrombotic microangiopathy after the administration of onasemnogene abeparvovec.95 Prophylactic complement inhibitors have now been incorporated into the protocol for the latter DMD trial for subsequent patients.96 If and how the complement system may affect the durability of gene therapy is still unknown, but since the complement system plays a role in augmenting adaptive immune processes, it could have a long-term impact on the expression of the therapeutic transgene.

Other mechanisms of the innate immune response

Less well-understood mechanisms of innate immunity that are not believed to have a significant impact on the success of gene therapy, but may have an unforeseen role in modulating subsequent long-term immune responses that could affect durability, include cytosolic DNA and RNA sensors.77 ITRs in the rAAV genome have inherent promoter activity, allowing the production of both sense and antisense RNA that can form dsRNA in the cytosol.97 dsRNA may be recognized by cytosolic RNA sensors (retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 [RIG-1] and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 [MDA-5]), leading to the production of IFN-β (Figure 4).77 For example, in mice engrafted with human hepatocytes and subsequently administered AAV8 vector expressing human FIX-Padua (R338L), expression of RIG-1 and MDA-5, as well as IFN-β, was higher at week 8 compared with untreated controls. Furthermore, blocking the dsRNA innate immune pathway increased transgene expression and inhibited IFN-β expression in AAV-transduced cells.97 This process may be of relevance to long-term durability since the production and subsequent immune recognition of dsRNA occurs after successful transduction.77,97

Mouse models indicate that sensing of IL-1 by IL-1Rs is critical for CD8+ T cell responses to the transgene product, especially at lower doses. However, at higher doses, other signaling pathways appear sufficient to invoke an immune response.98 The role of inflammasomes, which are important mediators of IL-1β-driven immune responses, is also being further characterized. Knockout mice appear to exhibit CD8+-driven responses despite lacking inflammasome machinery, suggesting that T cell activation in liver-directed gene therapy is independent of inflammasomes.99

Adaptive immune response to rAAV and the potential impact on durability

Early clinical trials of rAAV-mediated gene therapy highlighted the impact of the adaptive immune response on successful gene transfer.11,100,101 The adaptive immune response is considered the second line of defense, with the ability to elicit an antigen-specific response that targets and eliminates pathogens while developing immunological memory to protect against subsequent infections (Figure 5).79,83 As mentioned previously, the adaptive immune response is closely linked to the innate response, with the magnitude of response likely to be reliant on innate immune signals (Figures 3 and 4).77

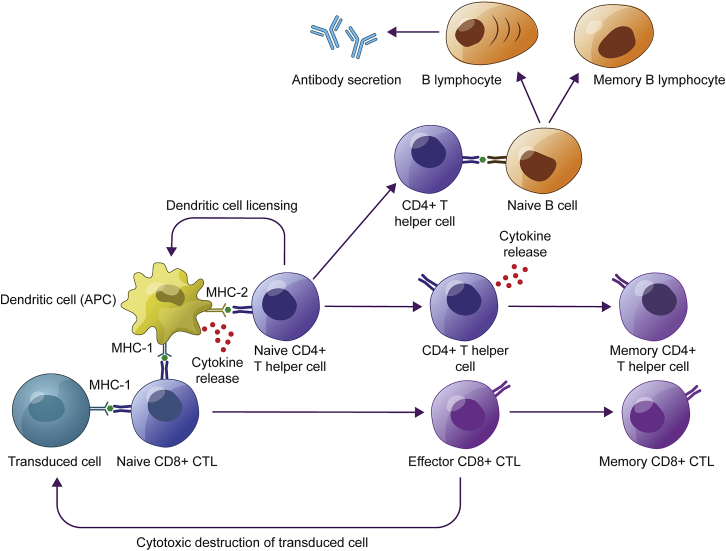

Figure 5.

Mechanisms of the adaptive immune system affecting durable transgene expression

Following rAAV vector administration and successful transduction, transduced cells present capsid-derived epitopes via MHC class I on the cell surface. This triggers the potential clearance of transduced cells by CTLs and recruitment of APCs, which are responsible for presenting antigens on their cell surfaces via MHC classes I and II. This, in turn, recruits additional CD8+ CTLs and CD4+ T helper cells and facilitates the release of antibodies by B cells, and establishment of a population of antigen-specific memory T and B cells.30,77,83,102 APC, antigen-presenting cell; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus.

Adaptive immune responses occur after the initial innate inflammatory response, resulting in a loss of transgene expression approximately 1–3 months after gene therapy administration.11,100,101,103 IFN-γ enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISpot) and flow cytometry can be used to estimate the presence of AAV capsid-specific CTLs both before and after gene therapy, but cellular responses are less commonly identified than antibody responses, likely due to the low number of lymphocytes found in the circulation.83 In the first clinical trial of gene therapy for hemophilia B, the first patient in the highest dose cohort achieved therapeutic levels of FIX transgene expression, but unlike in animals, which achieved stable long-term expression, a decline was observed after 4 weeks accompanied by a transient increase in liver transaminases and detection of AAV capsid-specific CTLs in the circulation.100 Similarly, T cell responses have been identified in clinical trials for neuromuscular disorders, although not always with a corresponding loss of expression.104,105 T cell responses, evidenced by IFN-γ ELISpot, following the administration of rAAV-mediated gene therapy, have now been observed in multiple clinical trials and have generally been successfully managed with the reactive or prophylactic administration of corticosteroids.103,105, 106, 107 The administration of corticosteroids may negatively affect B and T cell maturation.108 In a lipoprotein lipase deficiency gene therapy study, a 12-week course of steroids were started before gene therapy administration, and although capsid-specific T cells were generated, they appeared to lack cytotoxic properties.109 Of note, the cellular immune response to rAAV-mediated gene therapy is not always responsive to corticosteroids; for example, immune responses toward CpG-enriched vectors may not necessarily respond to steroid treatment.9,110

Hepatocellular injury, indicated by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations, has also been generally well managed with reactive or prophylactic administration of corticosteroids. Notably, ALT and AST elevations have been observed following rAAV gene therapy targeting other tissues; for example, following administration of onasemnogene abeparvovec for the treatment of SMA.111 Biodistribution studies have demonstrated that when rAAV vectors are infused intravenously, a substantial number of vectors will distribute to the liver even if they are targeting another organ.112, 113, 114, 115 Hepatocellular injury is therefore not only associated with liver-specific gene therapies and one should expect transient and often reversible effects with systemic rAAV gene therapy.

Although a relationship between dose and T cell response exists,11 there are inconsistencies between the observance of ALT and AST elevations and positivity on IFN-γ ELISpot,79,83 and these do not always correlate with the loss of transgene expression.116, 117, 118, 119

Role of regulatory T cells

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are vital for maintaining peripheral tolerance and preventing autoimmune disease, but they can also prevent effective viral clearance during chronic infection.120 In addition, in chronic infection, it is possible for T cells to exhibit an exhausted phenotype, characterized by the expression of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), whereby their functionality is severely impaired.120,121 It has been proposed that these T cells form a finely tuned population that is capable of a certain level of pathogen control without causing an overwhelming immune response.121 This exhausted phenotype has been observed in a Phase II trial (NCT01054339) of the intramuscular administration of AAV1-mediated gene therapy for the monogenic disorder AAT deficiency and was not associated in a decline in expression.122 More recent data from this particular trial has supported the hypothesis that Tregs and exhausted T cell populations can modulate the CTL response to the AAV capsid.123

In a Phase II clinical trial investigating an rAAV vector expressing human AAT for the treatment of AAT deficiency, a T cell response to the rAAV capsid was observed with no loss of AAT transgene expression, suggesting that an immune tolerance mechanism may have been involved.124 On further investigation, an expansion of Tregs was identified in situ as well as T cells with the exhausted phenotype. The group also identified intact capsids up to 1 year post-administration, potentially explaining the sustained presence of Tregs and exhausted T cells within the injected muscle, as would be expected during a chronic infection.124 After 5 years, these patients have sustained expression of the AAT transgene and continued evidence of infiltrated Tregs and exhausted CD8+ T cells in situ.40 This is a promising finding in terms of the durability of gene therapy, although the mechanism behind this tolerance requires further investigation, particularly in regard to the dose, transgene, and/or route of administration.40,120

Bystander activation

Why cellular immune responses vary between individuals and are often difficult to predict is an area of debate. An established concept of cellular immunity is the requirement for co-stimulatory signals alongside antigen presentation for a T cell response to occur.125 However, some believe that a process called bystander activation can occur when a pool of circulating memory T cells are activated by a subsequent unrelated virus, in the absence of specific antigen presentation for the original virus, through the release of cytokines and Toll-like receptor agonists by cells of the innate immune system, resulting in rapid, innate-like CTL destruction of infected cells.125,126 This points toward the importance of innate immune mediators and inflammation for subsequent T cell responses to the rAAV capsid and transgene. The impact of this mechanism on the durability of gene therapy is not known.

Adaptive response to the transgenic protein

Cellular immune responses against transgenic proteins, although rare, have been observed in some clinical trials. Mutation status may affect the risk of an immune response, given that those with null mutations (cross-reactive immunological material [CRIM] negative) are more likely to recognize the transgenic protein as foreign and develop more severe antibody and T cell responses than individuals who express the endogenous protein in some form.127,128 In clinical trials, additional immunosuppressive regimens have been shown to prevent responses to the transgenic protein in CRIM-negative individuals.127, 128, 129, 130

In a Phase I trial (NCT00428935) of intramuscular delivery of rAAV2 vectors carrying the mini-dystrophin gene under the control of a CMV promoter for the treatment of DMD (NCT00428935), no patient (N = 6) achieved long-term transgene expression (as measured on days 42 or 90), prompting further investigation. Spontaneously primed T cells were unexpectedly detected in two patients before the administration of gene therapy, with a rapid T cell response observed in one of the two patients following gene transfer, suggesting that while the mini-dystrophin protein was able to trigger memory T cells in one of the patients, the level of expression was not sufficient to elicit a response in the other.131

In a Phase II trial (NCT01054339) of intramuscular administration of AAV1-mediated gene therapy for the monogenic disorder AAT deficiency, one patient experienced a sustained and persistent T cell response against the transgene product, with a corresponding lower transgene expression than the other subjects who received the same dose. It was hypothesized that this was due to the presence of a rare human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-C allele in this patient that efficiently presented a peptide from the transgene-derived protein. Furthermore, polymorphisms in the AAT protein expressed by this patient may have resulted in a lack of tolerance to the transgene, which, when combined with an inflammatory response to the vector, resulted in a robust T cell response to the transduced cells.122 However, in an earlier Phase II clinical trial investigating an rAAV vector expressing human AAT, a T cell response to a single AAT peptide was detected in one subject, with no evidence of clinical effect (symptoms, antibody response, abnormal liver function tests, or AAT concentration).116

In NHP models, durable expression was observed at more than 6 years, as of 2005, after intramuscular injection of an rAAV vector encoding an inducible erythropoietin transgene, and no response was observed to erythropoietin or regulatory proteins in either the constitutive or regulated gene expression studies.132 More recently, durable expression was observed in NHPs 5 years after intravenous locoregional infusion of an rAAV2/1 vector encoding an inducible erythropoietin reporter gene, with no evidence of an immune response to the transgene product.133,134 The same group further tested the potential of a T cell response to the transgenic protein delivering a high-dose self-complementary (rather than the less immunogenic single-stranded) rAAV8 vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) via locoregional intravenous injection in an immunogenic NHP model. Despite the group using both an immunogenic recipient and transgene product, long-term transgene expression was achieved. Interestingly, analysis showed both a humoral and cellular immune response to the transgenic GFP protein that did not appear to affect expression levels.133 Two important conclusions may be drawn from this pre-clinical study: first, the route of administration appears to affect the potential for a deleterious immune response following gene therapy, perhaps due to the increased risk of an inflammatory response; and second, Tregs may play a role in regulating the CTL response to the AAV capsid and transgene product, helping to maintain stable transgene expression.133

Even though CTL responses to transgenes have been observed in NHPs following the systemic delivery of liver-directed AAV gene therapy, no immune responses against transgenic proteins have been reported to date in clinical trials of liver-directed gene therapy,103,106,118 potentially due to the tolerizing effects of expression in this organ.83 In fact, in FVIII or FIX antibody-prone dog models of hemophilia A and B, liver-directed rAAV gene therapy has been shown to have a tolerizing effect, with the ability to eradicate preexisting antibodies against the therapeutic protein (inhibitors).135, 136, 137

Factors affecting the immune responses to the rAAV vector and transgene

Both the extent and impact of immune responses to gene therapy are often difficult to predict83 and can vary according to the characteristics of the recipient (eg, underlying mutation/prior exposure to transgenic protein or HLA phenotype), characteristics of the vector and transgene, including impurities introduced during manufacturing, route of administration, and dose, as well as the target cell population.79,122

Different AAV capsids vary in terms of immunogenicity,83 with those that target antigen-presenting cells (APCs) more likely to activate a more potent CTL response.82 It has been shown that small differences in amino acid sequence can have a significant impact on the magnitude of the CTL response to the AAV capsid.121,138,139 For example, converting the amino acids RGNR to SGNT in the heparin-binding motif of rAAV2 reduced the CTL response to the capsid.139 Therefore, the choice of vector and modifications could have an impact on the durability of treatment.

Impurities in rAAV vector preparations may affect the immunogenicity of gene therapy. The presence of empty capsids increases the viral load without the benefit of delivering the transgene of interest, increasing the amount of antigenic material and thus the likelihood of an innate or adaptive immune response, with potential implications for durability.140,141 Some suggest that empty capsids can be used as decoys to reduce the impact of preexisting NAbs to the rAAV vector;142 however, in a hemophilia B gene therapy study, it was demonstrated that removing empty capsids from the final preparation did not increase the incidence of immune responses.2 It is also likely that this strategy would increase the risk of an innate or cellular adaptive response, including complement activation, without any therapeutic benefits.141 How exactly empty capsids affect the potential immune response to rAAV gene therapy remains a topic of scientific debate.

Approaches to addressing immunological considerations for durability

Several approaches are being used to manage or prevent an immune response to rAAV gene therapy to improve expression levels and long-term durability, as noted below.

Immunosuppression

A number of immunosuppressive treatments are available, and the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of various immunosuppression approaches are detailed elsewhere.143 We focus on some of the approaches being used alongside rAAV gene therapies.

A commonly used strategy to combat T cell responses in clinical trials involves the use of the corticosteroids prednisolone or prednisone, either in response to elevated liver enzymes or prophylactically;9,89,103,105,106 however, this is not always sufficient to recover transgene expression.9,89 In a Phase I/II trial investigating DTX101, an AAVrh10 expressing a codon-optimized FIX gene without CpG reduction (96 CpG motifs in the open reading frame),90 for the treatment of hemophilia B, two patients whose ALT elevations were initially managed using steroids experienced subsequent mild ALT elevations after the steroid course ended, resulting in a loss of FIX expression.89

Immunosuppressants other than corticosteroids have been considered, including in a Phase I trial (NCT02362438) of intrathecal delivery of an rAAV vector for the treatment of giant axonal neuropathy (sirolimus and tacrolimus),83 in a Phase I trial (NCT03369444) of FLT180a, a synthetic AAV vector containing a codon-optimized F9 gene, for the treatment of hemophilia B (tacrolimus),144 and a Phase I/II trial of SPK-8016, an rAAV vector containing a B-domain-deleted F8 expression cassette, for the treatment of hemophilia A (azathioprine and tacrolimus in two patients).145 Both hemophilia trials are ongoing and the immunomodulatory regimens are still being optimized.144,145

Antigenic peptides are presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules following proteasomal degradation of rAAV capsids;19 therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that proteasome inhibitors can be used to block CTL responses by preventing capsid breakdown and antigen presentation on MHC class I.146 Co-administration of bortezomib, a clinically approved proteasome inhibitor, with rAAV vectors to human hepatocytes resulted in increased transduction in vitro and dose-dependent inhibition of CTL destruction of transduced cells, consistent with reduced peptide-MHC presentation on the cell surface. The use of proteasome inhibitors in clinical studies remains to be determined.

Another novel approach to immunosuppression is the use of synthetic nanoparticles encapsulating sirolimus, which, when co-administered with rAAV vectors in previously exposed mice and NHPs, were able to inhibit CTL infiltration in the liver and memory T cell responses.147

Other immunosuppressive regimens have been considered, such as those used for transplant patients, but appear to be associated with an increase in CTLs and/or a decrease in AAV antigen-specific CD4+ Tregs.148,149 In a study of NHPs receiving an infusion of rAAV2-human (h)FIX through the hepatic artery, an IL-2R antibody (daclizumab) was included as part of the immunosuppression regimen. Immunosuppressant withdrawal led to increased immune response in treated animals, suggesting that blocking the IL-2R may have prevented the activation of CD4+/CD25+ Tregs.148

It is important to consider both the type and timing of immunosuppression used to maintain long-term durability of expression, particularly after the immunosuppressive regimen ends.

Administration route and dose

Route of administration is an important factor in the extent of an immune response to the rAAV vector. Administration to immune-privileged sites such as the CNS and eye may protect the vector and gene therapy product from detection by the immune system and improve durability compared with other routes of administration.79,150 Locoregional intravenous delivery has been shown to reduce inflammatory and subsequent T cell responses compared with intramuscular delivery, with the potential for improved durability versus direct tissue administration.133

Dose is also an important consideration since higher vector doses are more likely to be detected by the immune system, resulting in the loss of expression due to the elimination of transduced cells, as well as the potential for serious adverse events, including death, likely due to the innate immune response.83,107,151

Engineering the rAAV capsid and genome to reduce immunogenicity

There are various methods of rAAV capsid and genome engineering, with several approaches aimed at de-targeting the vector from the immune system.72,82 For example, as mentioned previously, unmethylated CpG motifs can be recognized by the innate immune system and engineering the rAAV genome to remove these CpG motifs can improve durability by evading MHC II expression and T cell responses.86 CpG motifs are present in both the expression cassette and the ITRs. Immune responses may be induced by the presence of a single CpG motif.152 Therefore, eliminating CpG motifs from the ITRs may further reduce AAV immunogenicity. A recent report of a mouse study indicates that CpG motifs can be depleted from the ITRs without compromising the biological activity of the vector.152 An alternative strategy, known as TLR9 cloaking, is to incorporate short DNA oligonucleotides (TLR9i) into the vector genome to antagonize TLR9 activation, potentially by outcompeting the CpG motifs.153

Another option is to use cis-acting regulatory elements within the rAAV transgene to tailor tissue specificity and the level of transgene expression.154 Promoters are a major cis-element that can be used to target immune-privileged sites such as the CNS, or tolerogenic tissue such as the liver, which can prevent detection by the immune system or induce immune tolerance, respectively, and could result in improved durability compared with other tissues.13,79,83,154,155 For example, AAV1- and AAV8-mediated delivery of immunoglobulin G1 transgene resulted in antibody responses in Rhesus monkeys receiving the rAAV vectors under control of muscle-specific but not liver-specific promoters.156

Promoter optimization could also be used to reduce the required vector dose, and thus the viral load. For example, use of a strong enhancer element upstream of a tissue-specific promoter can allow for strong transgene expression in the desired tissue.100,154,157,158 More recently, in silico engineering of a muscle-specific promoter, Sk-CRM4/Des, within a self-complementary AAV9 vector, resulted in up to 173-fold increased luciferase transgene expression in mice compared with the CMV promoter, with no evidence of apoptosis or T cell infiltration.159 It is also possible to use high-expression or high-specific activity constructs to increase expression at lower doses; for example, a naturally occurring high-specific activity FIX-Padua variant is widely used in hemophilia B gene therapy.106,160

Furthermore, micro (mi)RNA elements can be used to de-target expression in certain cell types, such as APCs, which may be useful in preventing adaptive immune responses.82,161,162 This approach was first demonstrated in lentiviral vectors containing target sequences for miR-142-3p, which allowed transgene expression in non-hematopoietic cells and suppression of expression in intravascular and extravascular hematopoietic lineages in mice.161 miR-142 binding sites (BSs) were then added to rAAV vectors to repress co-stimulatory signals in dendritic cells, significantly dampening the CTL response against the transgene and clearance of transduced cells, and thus allowing sustained expression of the highly immunogenic ovalbumin (OVA) transgene protein in skeletal myoblasts in mice.162 Subsequently, the combination of the miR-142BS and miR652-5pBS was shown to further block the activation of T cells and release of antibodies against the OVA transgene, inhibiting the activation of T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cells more effectively than miR-142BS alone.153 There are now several miRNA-regulated AAV vectors under investigation for gene therapy, particularly for preventing expression in the heart (miR-1), or liver and/or skeletal muscle (miR-122).163,164

Alternatively, mimicking a strategy used by viruses—expression of small proteins that interfere with antigen presentation (VIPRs)—could help the rAAV vector evade immune detection.165 For example, in mouse models, administration of AAV vectors either containing the AAT/OVA or mini-dystrophin protein transgenes fused to the ICP47 VIPR resulted in the inhibition of antigen-specific CTL responses against the capsid compared with no VIPR controls, with stable transgene expression achieved for the AAV-AAT/OVA vectors.165

Another method under investigation harnesses a powerful immunosuppressive mechanism specific to a transgene expressed in the eye, known as subretinal-associated immune inhibition.166 This involves introducing peptides from the transgene product into the subretinal space to elicit systemic antigen-specific immunosuppression.166 In mice, co-injection of the HY male antigen peptide with an AAV8 vector containing the HY transgene inhibited both CD8+ CTL and CD4+ T cell-specific primary and memory responses against HY compared with injection of the AAV8-HY vector without the peptide.167,168

Immunotolerance induction

Based on the observed tolerogenic profile of the liver and the role of Tregs in immune homeostasis, some groups are investigating the ability to tolerize individuals to the rAAV vector.83,169, 170, 171 One approach is exposure to a foreign antigen, while using sirolimus to induce T cell anergy or deletion, and inhibiting the stimulation of dendritic cells and the mechanistic target of rapamycin-independent Treg signaling, resulting in a pool of antigen-specific CD4+CD25+FoxP+ Tregs.169,170 In a hemophilia B mouse model (with a targeted F9 deletion), a 1-month protocol involving repeated administration of IL-10, sirolimus, and a hFIX-specific peptide before intramuscular administration of AAV1-CMV-hFIX resulted in the deletion of effector T cells and induction of Tregs, leading to low or undetectable hFIX antibodies (inhibitors) and higher hFIX expression compared with non-tolerized mice.171 The group went on to show that the combination of sirolimus, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, and FVIII antigen in hemophilia A mice resulted in lower inhibitor titers compared with untreated mice following weekly intravenous exposure to FVIII. They also showed that sirolimus was essential for the induction of tolerance.170 Another tolerization approach is to administer antigens orally. For example, prophylactic oral administration of the highly immunogenic protein OVA before intramuscular administration of AAV-OVA was able to prevent antibody formation and CTL responses to the transgene product, resulting in improved long-term transgene persistence and expression.172

In another study, taking advantage of the fetal immune system, intravenous administration of AAV-rh10 OVA-2A-GFP to a neonatal NHP followed by subsequent administration of AAV9 OVA-2A-GFP at 4 months resulted in sustained transgene expression for more than 1 year, demonstrating that operational tolerance to transgene-encoded proteins is possible in an NHP with an immune system similarly developed at birth to that of the human neonate.173 Similarly, in an NHP study investigating rAAV9 gene therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis type I gene therapy, animals tolerized at birth using an AAV8 vector expressing human α-1-iduronidase (IDUA) sustained transgene expression in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compared with non-tolerized animals in which antibodies led to the loss of the IDUA levels in the CSF.174 Whether these tolerization strategies can be applied to improve the durability of gene therapy in humans remains to be seen.

A look to the future

Many unknowns remain about the durability of rAAV gene therapy and it will not be possible to draw firm conclusions until sufficient time has elapsed with a large enough cohort of patients for each of the proposed applications. While the data are promising, with durable responses being reported up to 10 years post-administration in various studies,2,3 it has yet to be determined how this will play out in the real-world setting over the longer term.

Although we have concentrated here on the biology of rAAV vectors, there are several lifestyle considerations and other patient factors that may also affect durability. For example, excessive alcohol use after liver-directed gene therapy could result in the elimination of large numbers of transduced hepatocytes following liver-directed therapy. In some trials, patients must abstain from alcohol for up to 1 year after infusion.175 Patients who live for many decades after gene therapy will be at the same risk of the diseases of aging as the general population, and the potential impact of these diseases on long-term transgene expression has yet to be investigated.

In general, rAAV-based therapies are likely to be submitted for regulatory approval before the full extent of durability has been demonstrated. In the absence of long-term durability data from clinical trials, data modeling is one option that can be explored. In recommending voretigene neparvovec, the UK NICE reviewed modeled durability data provided by the manufacturer and concluded that the estimate value for durability of 40 years was “uncertain but reasonable.”7

Furthermore, complementing the data from clinical trials with real-world evidence after regulatory approval is essential. Registries that collect harmonized data on patients who have received gene therapy need to be in place to collect long-term data on durability, real-world effectiveness, as well as the safety of rAAV gene therapies. All stakeholders, including patient groups, physicians, researchers, policy makers, payers and industry, need to work together to address the remaining unknowns.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Sophie Day and Debbie McIntosh of Synergy Medical and Belinda Adams of Med Pen, and funded by Pfizer Inc. The authors thank Drs Stephen Kagan, Clark Pan, Ian Winburn, and Matthias Mahn for their critical review of the manuscript. G.G. has received research grant support from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS076991-01, 4P01HL131471-02, UG3 HL14736701, R01HL097088, U19 AI149646-01, R01 HL152723-01A1, and UH3 HL147367-04).

Author contributions

All of the authors collaborated in the preparation of the manuscript, and critically reviewed and provided revisions to the manuscript. Allof the authors granted final approval of the manuscript for submission.

Declaration of interests

D.I.L., M.S., and D.M. are employees of Pfizer Inc. and may own stock/options in the company. M.M. and G.G declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sehara Y., Fujimoto K.I., Ikeguchi K., Katakai Y., Ono F., Takino N., Ito M., Ozawa K., Muramatsu S.I. Persistent expression of dopamine-synthesizing enzymes 15 years after gene transfer in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2017;28:74–79. doi: 10.1089/humc.2017.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathwani A.C., Reiss U., Tuddenham E., Chowdary P., McIntosh J., Riddell A., Pie J., Mahlangu J.N., Recht M., Shen Y.-M., et al. Adeno-associated mediated gene transfer for Hemophilia B: 8 year follow up and impact of removing “empty viral particles” on safety and efficacy of gene transfer [abstract] Blood. 2018;132:491. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchlis G., Podsakoff G.M., Radu A., Hawk S.M., Flake A.W., Mingozzi F., High K.A. Factor IX expression in skeletal muscle of a severe hemophilia B patient 10 years after AAV-mediated gene transfer. Blood. 2012;119:3038–3041. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-382317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaudet D., Stroes E.S., Methot J., Brisson D., Tremblay K., Bernelot Moens S.J., Iotti G., Rastelletti I., Ardigo D., Corzo D., et al. Long-term retrospective analysis of gene therapy with alipogene tiparvovec and its effect on lipoprotein lipase deficiency-induced pancreatitis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:916–925. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maguire A.M., High K.A., Auricchio A., Wright J.F., Pierce E.A., Testa F., Mingozzi F., Bennicelli J.L., Ying G.S., Rossi S., et al. Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1597–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61836-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maguire A.M., Russell S., Chung D.C., Yu Z.F., Tillman A., Drack A.V., Simonelli F., Leroy B.P., Reape K.Z., High K.A., et al. Durability of voretigene neparvovec for biallelic RPE65-mediated inherited retinal disease: phase 3 results at 3 and 4 years. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:1460–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voretigene Neparvovec for Treating Inherited Retinal Dystrophies Caused by RPE65 Gene Mutations. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hst11/documents/final-evaluation-determination-document-2. Accessed: December, 2021.

- 8.BioMarin provides additional data from recent 4 year update of ongoing phase 1/2 study of valoctocogene roxaparvovec gene therapy for severe Hemophilia A in late-breaking oral presentation at World Federation of Hemophilia Virtual Summit [press release]. Biomarin, 2020. Available at: https://investors.biomarin.com/2020-06-17-BioMarin-Provides-Additional-Data-from-Recent-4-Year-Update-of-Ongoing-Phase-1-2-Study-of-Valoctocogene-Roxaparvovec-Gene-Therapy-for-Severe-Hemophilia-A-in-Late-Breaking-Oral-Presentation-at-World-Federation-of-Hemophilia-Virtual-Summit. Accessed: December, 2021.

- 9.Konkle B.A., Walsh C.E., Escobar M.A., Josephson N.C., Young G., von Drygalski A., McPhee S.W.J., Samulski R.J., Bilic I., de la Rosa M., et al. BAX 335 hemophilia B gene therapy clinical trial results: potential impact of CpG sequences on gene expression. Blood. 2021;137:763–774. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leavitt A.D., Konkle B.A., Stine K., Visweshwar N., Harrington T.J., Giermasz A., Arkin S., Fang A., Plonski F., Smith L., et al. Updated follow-up of the Alta study, a phase 1/2 study of giroctocogene fitelparvovec (SB-525) gene therapy in adults with severe Hemophilia A [abstract] Blood. 2020;136:12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathwani A.C., Tuddenham E.G., Rangarajan S., Rosales C., McIntosh J., Linch D.C., Chowdary P., Riddell A., Pie A.J., Harrington C., et al. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2357–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasi K.J., Rangarajan S., Mitchell N., Lester W., Symington E., Madan B., Laffan M., Russell C.B., Li M., Pierce G.F., et al. Multiyear follow-up of AAV5-hFVIII-SQ gene therapy for Hemophilia. A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:29–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naso M.F., Tomkowicz B., Perry W.L., 3rd, Strohl W.R. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31:317–334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flotte T., Carter B., Conrad C., Guggino W., Reynolds T., Rosenstein B., Taylor G., Walden S., Wetzel R. A phase I study of an adeno-associated virus-CFTR gene vector in adult CF patients with mild lung disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 1996;7:1145–1159. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.9-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flotte T.R. Birth of a new therapeutic platform: 47 years of adeno-associated virus biology from virus discovery to licensed gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1976–1981. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz E.D., Rahman K.S., Bower B.D., Dismuke D.J., Falvo M.R., Griffith J.D., Harvey S.C., Asokan A. Biophysical and ultrastructural characterization of adeno-associated virus capsid uncoating and genome release. J. Virol. 2013;87:2994–3002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03017-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C., Samulski R.J. Engineering adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;21:255–272. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulcha J.T., Wang Y., Ma H., Tai P.W.L., Gao G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6:53. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colella P., Ronzitti G., Mingozzi F. Emerging issues in AAV-mediated in vivo gene therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;8:87–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penaud-Budloo M., Le Guiner C., Nowrouzi A., Toromanoff A., Chérel Y., Chenuaud P., Schmidt M., von Kalle C., Rolling F., Moullier P., et al. Adeno-associated virus vector genomes persist as episomal chromatin in primate muscle. J. Virol. 2008;82:7875–7885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00649-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi V.W., McCarty D.M., Samulski R.J. Host cell DNA repair pathways in adeno-associated viral genome processing. J. Virol. 2006;80:10346–10356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00841-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakai H., Storm T.A., Fuess S., Kay M.A. Pathways of removal of free DNA vector ends in normal and DNA-PKcs-deficient SCID mouse hepatocytes transduced with rAAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003;14:871–881. doi: 10.1089/104303403765701169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cataldi M.P., McCarty D.M. Hairpin-end conformation of adeno-associated virus genome determines interactions with DNA-repair pathways. Gene Ther. 2013;20:686–693. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi V.W., Samulski R.J., McCarty D.M. Effects of adeno-associated virus DNA hairpin structure on recombination. J. Virol. 2005;79:6801–6807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6801-6807.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathwani A.C., Rosales C., McIntosh J., Rastegarlari G., Nathwani D., Raj D., Nawathe S., Waddington S.N., Bronson R., Jackson S., et al. Long-term safety and efficacy following systemic administration of a self-complementary AAV vector encoding human FIX pseudotyped with serotype 5 and 8 capsid proteins. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:876–885. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen G.N., Everett J.K., Kafle S., Roche A.M., Raymond H.E., Leiby J., Wood C., Assenmacher C.A., Merricks E.P., Long C.T., et al. A long-term study of AAV gene therapy in dogs with hemophilia A identifies clonal expansions of transduced liver cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39:47–55. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0741-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batty P., Sihn C.R., Ishida J., Mo A.M., Yates B., Brown C., Harpell L., Pender A., Russell C., Sardo Infirri S., et al. Long-term vector genome outcomes and immunogenicity of AAV FVIII gene transfer in the Hemophilia A dog model [abstract PB1087] Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;4:549. [Google Scholar]

- 28.George L.A., Ragni M.V., Rasko J.E.J., Raffini L.J., Samelson-Jones B.J., Ozelo M., Hazbon M., Runowski A.R., Wellman J.A., Wachtel K., et al. Long-term follow-up of the first in human intravascular delivery of AAV for gene transfer: AAV2-hfix16 for severe Hemophilia B. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2073–2082. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kattenhorn L.M., Tipper C.H., Stoica L., Geraghty D.S., Wright T.L., Clark K.R., Wadsworth S.C. Adeno-associated virus gene therapy for liver disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:947–961. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandamme C., Adjali O., Mingozzi F. Unraveling the complex story of immune responses to AAV vectors trial after trial. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017;28:1061–1074. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan A.W., Dorrell C., Grompe M. Stem cells and liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:466–481. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magrassi L., Leto K., Rossi F. Lifespan of neurons is uncoupled from organismal lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:4374–4379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217505110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spalding K.L., Bhardwaj R.D., Buchholz B.A., Druid H., Frisen J. Retrospective birth dating of cells in humans. Cell. 2005;122:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sender R., Milo R. The distribution of cellular turnover in the human body. Nat. Med. 2021;27:45–48. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes J.R., Levchenko V.A., Blanksby S.J., Mitchell T.W., Williams A., Truscott R.J.W. No turnover in lens lipids for the entire human lifespan. Elife. 2015;4:e06003. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baruteau J., Waddington S.N., Alexander I.E., Gissen P. Gene therapy for monogenic liver diseases: clinical successes, current challenges and future prospects. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:497–517. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coppoletta J.M., Wolbach S.B. Body length and organ weights of infants and children: a study of the body length and normal weights of the more important vital organs of the body between birth and twelve years of age. Am. J. Pathol. 1933;9:55–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyaoka Y., Miyajima A. To divide or not to divide: revisiting liver regeneration. Cell Div. 2013;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.EMA Decision P/0218/2019. European Medicines Agency (EMA), 2019. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/pip-decision/p/0218/2019-ema-decision-17-june-2019-agreement-pip-granting-deferral-adeno-associated-viral-vector_en.pdf Accessed: December, 2021.

- 40.Mueller C., Gernoux G., Gruntman A.M., Borel F., Reeves E.P., Calcedo R., Rouhani F.N., Yachnis A., Humphries M., Campbell-Thompson M., et al. 5 year expression and neutrophil defect repair after gene therapy in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendell J.R., Al-Zaidy S.A., Lehman K.J., McColly M., Lowes L.P., Alfano L.N., Reash N.F., Iammarino M.A., Church K.R., Kleyn A., et al. Five-year extension results of the phase 1 START trial of onasemnogene abeparvovec in spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:834–841. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalwadi D.A., Calabria A., Tiyaboonchai A., Posey J., Naugler W.E., Montini E., Grompe M. AAV integration in human hepatocytes. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2898–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gil-Farina I., Fronza R., Kaeppel C., Lopez-Franco E., Ferreira V., D'Avola D., Benito A., Prieto J., Petry H., Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G., et al. Recombinant AAV integration is not associated with hepatic genotoxicity in nonhuman primates and patients. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:1100–1105. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.uniQure announces findings from reported case of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Hemophilia B gene therapy program. uniQure, Available at: http://www.uniqure.com/PR_HCC%20Investigation%20Findings%20_3_29_21_FINAL.pdf. Accessed: December, 2021.

- 45.Hüser D., Gogol-Döring A., Lutter T., Weger S., Winter K., Hammer E.M., Cathomen T., Reinert K., Heilbronn R. Integration preferences of wildtype AAV-2 for consensus rep-binding sites at numerous loci in the human genome. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000985. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weitzman M.D., Kyöstiö S.R., Kotin R.M., Owens R.A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith R.H. Adeno-associated virus integration: virus versus vector. Gene Ther. 2008;15:817–822. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCown T.J., Xiao X., Li J., Breese G.R., Samulski R.J. Differential and persistent expression patterns of CNS gene transfer by an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. Brain Res. 1996;713:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiao C., Yuan Z., Li J., He B., Zheng H., Mayer C., Li J., Xiao X. Liver-specific microRNA-122 target sequences incorporated in AAV vectors efficiently inhibits transgene expression in the liver. Gene Ther. 2011;18:403–410. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tenenbaum L., Chtarto A., Lehtonen E., Velu T., Brotchi J., Levivier M. Recombinant AAV-mediated gene delivery to the central nervous system. J. Gene Med. 2004;6:S212–S222. doi: 10.1002/jgm.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tolmachov O., Subkhankulova T., Tolmachova T. In: Gene Therapy - Tools and Potential Applications. Martin Molina F., editor. IntechOpen; 2013. Silencing of transgene expression: a gene therapy perspective; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakai H., Herzog R.W., Hagstrom J.N., Walter J., Kung S.H., Yang E.Y., Tai S.J., Iwaki Y., Kurtzman G.J., Fisher K.J., et al. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated gene transfer of human blood coagulation factor IX into mouse liver. Blood. 1998;91:4600–4607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray S.J., Foti S.B., Schwartz J.W., Bachaboina L., Taylor-Blake B., Coleman J., Ehlers M.D., Zylka M.J., McCown T.J., Samulski R.J. Optimizing promoters for recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression in the peripheral and central nervous system using self-complementary vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011;22:1143–1153. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein R.L., Meyer E.M., Peel A.L., Zolotukhin S., Meyers C., Muzyczka N., King M.A. Neuron-specific transduction in the rat septohippocampal or nigrostriatal pathway by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Exp. Neurol. 1998;150:183–194. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paterna J.C., Moccetti T., Mura A., Feldon J., Büeler H. Influence of promoter and WHV post-transcriptional regulatory element on AAV-mediated transgene expression in the rat brain. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1304–1311. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore L.D., Le T., Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellis J. Silencing and variegation of gammaretrovirus and lentivirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005;16:1241–1246. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorincz M.C., Schübeler D., Goeke S.C., Walters M., Groudine M., Martin D.I. Dynamic analysis of proviral induction and de novo methylation: implications for a histone deacetylase-independent, methylation density-dependent mechanism of transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:842–850. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.842-850.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Léger A., Le Guiner C., Nickerson M.L., McGee Im K., Ferry N., Moullier P., Snyder R.O., Penaud-Budloo M. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated transgene expression is independent of DNA methylation in primate liver and skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Golebiowski D., van der Bom I.M.J., Kwon C.S., Miller A.D., Petrosky K., Bradbury A.M., Maitland S., Kuhn A.L., Bishop N., Curran E., et al. Direct intracranial injection of AAVrh8 encoding monkey beta-n-acetylhexosaminidase causes neurotoxicity in the primate brain. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017;28:510–522. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hiramatsu N., Chiang W.C., Kurt T.D., Sigurdson C.J., Lin J.H. Multiple mechanisms of unfolded protein response-induced cell death. Am. J. Pathol. 2015;185:1800–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rao R.V., Bredesen D.E. Misfolded proteins, endoplasmic reticulum stress and neurodegeneration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]