Summary

Despite health gains over the past 30 years, children and adolescents are not reaching their health potential in many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). In addition to health systems, social systems, such as schools, communities, families, and digital platforms, can be used to promote health. We did a targeted literature review of how well health and social systems are meeting the needs of children in LMICs using the framework of The Lancet Global Health Commission on high-quality health systems and we reviewed evidence for structural reforms in health and social sectors. We found that quality of services for children is substandard across both health and social systems. Health systems have deficits in care competence (eg, diagnosis and management), system competence (eg, timeliness, continuity, and referral), user experience (eg, respect and usability), service provision for common and serious conditions (eg, cancer, trauma, and mental health), and service offerings for adolescents. Education and social services for child health are limited by low funding and poor coordination with other sectors. Structural reforms are more likely to improve service quality substantially and at scale than are micro-level efforts. Promising approaches include governing for quality (eg, leadership, expert management, and learning systems), redesigning service delivery to maximise outcomes, and empowering families to better care for children and to demand quality care from health and social systems. Additional research is needed on health needs across the life course, health system performance for children and families, and large-scale evaluation of promising health and social programmes.

This is the fourth in a Series of four papers about optimising child and adolescent health and development

Introduction

A 2018 analysis estimated that 8·6 million deaths from treatable conditions occur annually, including more than 1 million deaths in neonates.1 Two-thirds of these infants were born in health facilities, showing that low-quality health systems, and not solely scarce access to care, undermine progress.1 The cumulative health and developmental losses in infants, children, and adolescents increasingly result from a failure of governance, implementation, and integration of policies and interventions across health systems and other social institutions.2

Health systems are crucial for child and adolescent health and wellbeing, but need to be augmented by social systems to reach this age group with promotive, preventive, and curative services relevant to their life stage. In this Series paper, the social systems that we examine include programmes and policies delivered by families, communities, schools, and digital platforms (appendix p 2). We use the definition of a quality health system from The Lancet Global Health Commission on high-quality health systems3 as one that is for people, that consistently delivers services that improve or maintain health, that builds trust in the population, and that adapts to changing population and health needs, including changing needs along a child's life course.

High-quality systems and health-promoting elements of social systems should be primarily judged by processes and health outcomes, confidence, and economic benefits. Furthermore, health and social systems need to empower families, as well as children and adolescents, to take an active role in their health that is consistent with their developmental course.

As Black and colleagues4 note in the first paper of this Series, human capital (ie, health, wellbeing, knowledge, and interpersonal and socioemotional skills) needed to achieve individual and societal potential is built though interactive biological, environmental, and behavioural processes that begin before conception and continue into childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. In the second Series paper, Victora and colleagues5 review data on key conditions related to human capital in children, adolescents, and adults, and analyse how early-life poverty contributes to their enduring prevalence throughout the life course. In the third paper of the Series, Vaivada and colleagues6 point to a large array of effective and affordable interventions to promote child health and development; however, large gaps in survival, health, and function remain between countries. These gaps reflect the difference between families' aspirations for their children and the reality of inadequate health and social systems.

In this fourth Series paper, we explore the quality of health systems and social systems (ie, service delivery platforms outside of health care) in promoting child health, with a focus on low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). We assess the performance of these systems in real-world settings, identify knowledge gaps, and propose structural and societal innovations that could help to overcome current challenges. We point to the crucial role of research into health systems to gauge large-scale effectiveness of new ideas.

Key messages.

-

•

Despite growing evidence of effective interventions, health and social systems (including family, community, and school programmes) are failing to implement these interventions to address the health needs of individuals from birth to adolescence

-

•

Preventive and curative care is often substandard, with low diagnostic accuracy, treatment delays, and non-adherence to evidence-based standards, and quality is often worst for low-income communities

-

•

Poor user experience for parents, children, and adolescents leads to non-adherence and low trust in health systems

-

•

These deficits in health system quality lead to excess morbidity and mortality in children and adolescents

-

•

Families, communities, schools, and digital platforms are well positioned to augment health systems, although research and investment are needed to identify the best means of designing and integrating services in coherent ways

-

•

Structural reforms are needed for high-quality health and social systems, including committed leadership, skilled management teams that are committed to learning, reorganisation of service delivery, and empowerment of children, adolescents, and families to recognise and demand quality care

-

•

A strong multisectoral approach can help to meet the aspirations of universal health coverage, limit the negative effects of COVID-19, and realise better health across childhood and adolescence

Methods

We used several literature scoping strategies to identify relevant evidence that describes the performance of health and social systems for children and adolescents in LMICs, as well as innovative structural strategies to improve child and adolescent health. We focused on the conditions that most contribute to mortality, morbidity, and disability in infants, children, and adolescents, including those that have been less explored in the context of LMICs (eg, preterm birth, infections, injuries, and depression).

To guide our search, we used the framework of care processes as reported in The Lancet Global Health Commission,3 comprising care competence (ie, provider provision of effective care), system competence (ie, safe, continuous, and integrated services over the course of care), and user experience (ie, respectful, convenient, and low-hassle care that is appropriate for each developmental stage). Outcomes included positive health outcomes for conditions treatable by health care, user confidence, and economic benefits and harms for users. Because the first4 and second5 papers in this Series examine mortality and morbidity, in this fourth Series paper, we report on the Commission's non-health outcomes (ie, financial protection and confidence). For non-health system platforms, we assessed the performance of the most common health-promoting activities for infants, children, and adolescents. Further details on the search strategy, including example search terms, are provided in the appendix (p 4).

To highlight innovations, we identified promising programmes for children in health and social sectors that were consistent with the key structural reforms proposed by the Commission.3 Within their sector of expertise, the authors drew on their disciplinary literatures, reviews, meta-analyses, previous Lancet Series,7, 8, 9, 10 and WHO–UNICEF evidence maps to identify novel approaches that adapted the Commission's recommendations to these new platforms. Methods used for primary visualisations, data synthesis, and data analysis based on publicly available data are described in the appendix (pp 4–12).

Health system quality for infants, children, and adolescents: care and system competence

Health needs in pregnancy and the neonatal period

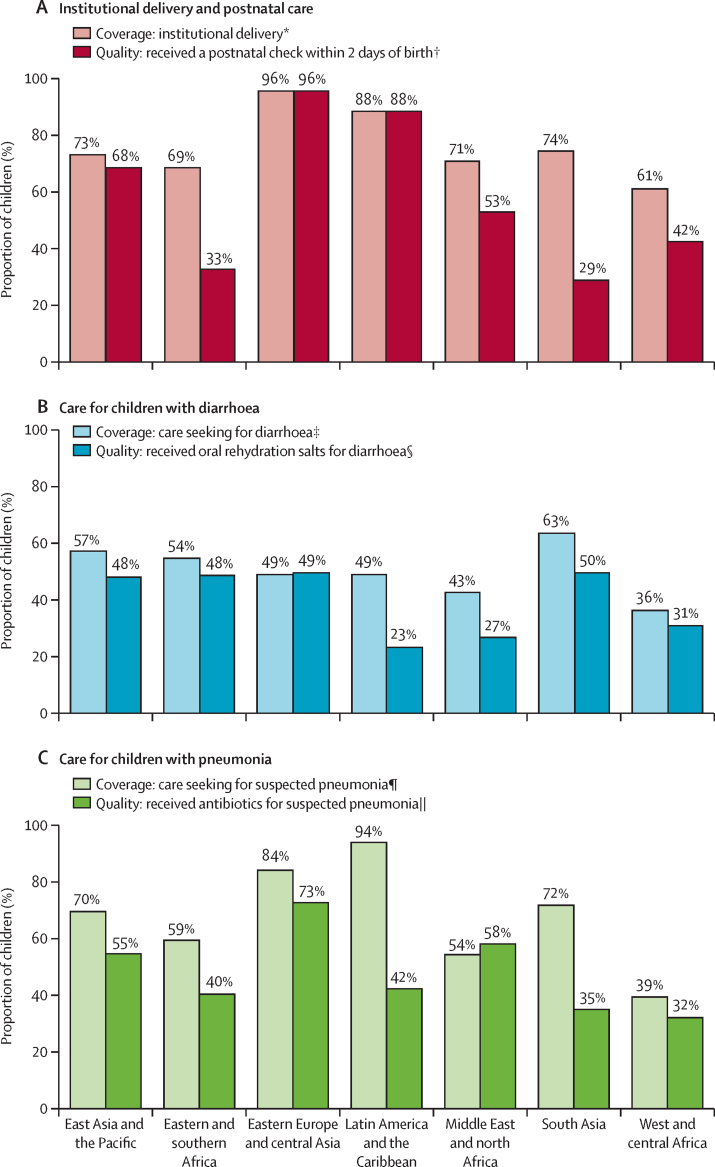

Despite progress, the number of neonatal deaths and stillbirths remains high in LMICs, with preterm births, intrapartum-associated complications, and infections as the leading causes of mortality.4, 11 Although three-quarters of all births in LMICs take place in health facilities (figure 1A), this high mortality rate is largely attributable to inadequate provision of rapid and effective treatments for obstetric and neonatal emergencies, which require a highly skilled, organised, and coordinated system response to save lives.14, 15, 16

Figure 1.

Coverage versus quality of care in the neonatal and early childhood periods by region

Data on coverage and quality of care provided for institutional delivery and postnatal care (A), care for children with diarrhoea (B), and care for children with suspected pneumonia. Data taken from the latest Demographic and Health Survey and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey conducted in 95 countries between 2010 and 2018.12, 13 Country-level estimates are weighted using individual survey weights and regional averages are weighted according to each country's weighted sample size. Countries, survey years, and regional classification are available in the appendix (pp 4–10). *Proportion of all live births in the past 3 or 5 years (Demographic and Health Survey) or last live birth in the past 2 years (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey) born in a health facility (n=97 countries). †Proportion of last live birth in the past 2 years who received postnatal care within 2 days of birth (n=82 countries). ‡Proportion of all children aged 0–59 months with diarrhoea in the past 2 weeks who sought care from an appropriate facility or provider (excluding traditional attendant, pharmacy, or shop; n=77 countries). §Proportion of all children aged 0–59 months with diarrhoea in the past 2 weeks who received oral rehydration solution (n=94 countries). ¶Proportion of all children aged 0–59 months with suspected pneumonia (ie, cough, short and rapid breaths, and problem in the chest) in the past 2 weeks for whom advice or treatment was sought from an appropriate facility or provider (excluding traditional attendant, pharmacy, or shop; n=90 countries). ||Proportion of all children aged 0–59 months with suspected pneumonia (ie, cough, short and rapid breaths, and problem in the chest) in the past 2 weeks who took antibiotics (n=84 countries).

Opportunities to prevent these deaths are missed even before birth. Despite how high-quality antenatal care can reduce risk of preterm birth, low birthweight, and stillbirth, only 73% of women who attended antenatal visits in 91 LMICs from 2007 to 2016 had their blood pressure measured and their urine and blood tested.7, 17, 18, 19 Across the 91 LMICs, the wealthiest women are four times more likely to report good quality antenatal care than are the poorest women.19

High-quality labour and delivery care, including rapid recognition of problems and provision of interventions (eg, caesarean section, blood transfusion, and resuscitation), could prevent 1·3 million intrapartum stillbirths.7 Care for babies with low birthweight and for sick newborn babies, who are at greatest risk of mortality, often does not reflect best practice guidelines.20 In Kenya, 45% of small and sick newborn babies who accessed a health facility received good quality care.21 In five sub-Saharan African countries, only 39% of health-care providers were able to correctly diagnose neonatal asphyxia.3 Medication errors for neonates were common, even in clinical training centres across Kenya.22 Although early postnatal care can detect problems and promote good health practices, across 82 LMICs, 58% of newborn babies received postnatal care within 48 h of birth (figure 1A; appendix pp 4–10).

Good quality neonatal care is hampered by shortages of key items, such as blood transfusion sets, positive airway pressure devices, kangaroo mother care, formulas, vitamin K, or intravenous penicillin.21 Additionally, provider performance is problematic for neonates who are commonly admitted to the wrong level of care and are inadequately monitored.23, 24 Many facilities serving neonates are severely understaffed and overcrowded, which inhibits infant monitoring.25

Early childhood: cognitive and socioemotional development

An estimated 249 million children younger than 5 years in LMICs experience poverty and growth stunting that threaten their development and 50 million children globally have a developmental disability that impairs physical, learning, or behavioural functioning.8, 26, 27, 28, 29 These risks can be mitigated by delaying pregnancy in adolescents, reducing birth asphyxia, improving nutrition, and supporting parental nurturing care, learning, secure attachment, and safety.9, 30, 31, 32 Especially when delivered during the first 1000 days after birth, health system and social interventions can improve physical and mental health across the life course.10, 33 Many of these programmes were disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic with potentially long-lasting adverse consequences, particularly for low-income communities.34

Childhood: infections and acute conditions

Immunisation is a highly cost-effective health system activity; however, in 2019, almost 20 million infants were unvaccinated or undervaccinated.35 Beyond immunisation, health-care providers in 17 LMICs performed only 41% of the clinical actions recommended by WHO.3 Performance was minimally better for severely ill children, indicating failure of differential diagnosis and detection.36 Studies from Kenya show inadequate assessment of children with fever; variable adherence to guidelines for treatment of pneumonia, meningitis, and malaria; and inadequate admission assessment and patient monitoring.37

Even simple interventions are inconsistently provided. In 94 LMICs, only 28% of children who sought care for diarrhoea received oral rehydration solution (figure 1B). A study of child deaths in Mali and Uganda found that most parents sought care but encountered multiple system failures, including provider failure to act on signs of serious illness, to prescribe essential medicines, and to refer to a higher level of care, as well as an inadequate response to observed parental neglect.38

Childhood and adolescence: injuries, trauma, and disability

More than 5% of children from birth to age 14 years live with a moderate or severe disability.39 In Africa, war and unintentional injuries are the second leading cause of disability in children.40 Prevalence of traumatic brain injuries is disproportionally concentrated in LMICs; the odds of dying from this type of injury in Uganda are more than four times higher than are those in high-income countries (HICs).41 Comprehensive injury care requires high-quality care across the health system, including prehospital care at the scene of the injury, transport to a trauma centre, an effective emergency department, operating room, intensive care unit, and rehabilitation services, which comprise a set of services not often available in LMICs.42 A survey of surgical hospitals in Zambia showed that only 14% of hospitals met the minimum criteria for paediatric surgical safety.43 Weak triage and delayed surgical interventions were blamed for the excess mortality from traumatic brain injury in Uganda.41

Childhood and adolescence: mental health

Mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, conduct disorders, and substance use, are an important contributor to poor health in children and adolescents.4 Gender-based violence is distressingly common and often leads to severe mental health sequelae.44 In adolescents globally, suicide is the second most common cause of death.33, 45 Preventive interventions can build mental health literacy, promote timely help seeking, reduce stigma, and decrease disparities when targeted to groups at high risk.33 Interventions need to be age-sensitive, given that risk factors and incidence shift across the life course.46 Despite the frequently early age of onset of incident mental disorders, children and adolescents access mental health services less frequently than do any other age group.33, 47 To compound this situation, mental health services for children and adolescents worldwide are frequently unavailable, underfunded, or of poor quality.33, 48

Childhood and adolescence: cancer

80% of children and adolescents with cancer globally live in LMICs, where access to high-quality care is scarce.49 For example, for treatable cancers that predominantly affect young children (eg, neuroblastoma), mean 5-year survival rates range from 6·7% in Africa and 24·5% in Asia to more than 80% in North America.50 Overall, 5-year survival rates for children in HICs are much higher than for those in LMICs (80% vs 30%).51, 52 Poor cancer outcomes for children in LMICs are due to delayed presentation and diagnosis, misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis, scarcity of specialised facilities and providers, treatment toxicity, treatment abandonment, excess relapse, drug shortages, and high prevalence of comorbidities (eg, malnutrition).52, 53, 54, 55 Family poverty has a negative effect on adherence to treatment for paediatric cancer.56, 57, 58 Furthermore, children in LMICs have poor access to palliative care.49, 52

Adolescence: sexual and reproductive health

Delaying early pregnancy (ie, before age 18 years) is crucial for improving maternal and child health and social wellbeing, yet 66 million women aged 20–24 years were married before age 18 years between 2003 and 2016.59, 60 In LMICs, adolescent girls are less likely to use modern contraceptives than are older women (appendix p 3).59

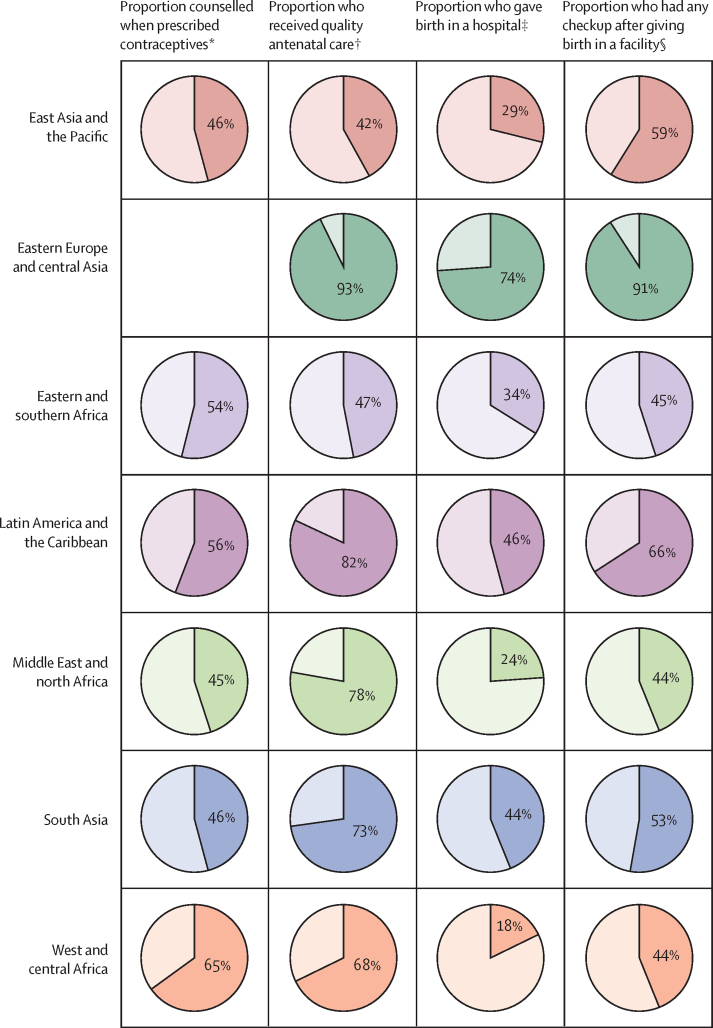

Beyond access to family planning services, the quality of these resources remains poor in many LMICs for both adolescents and older women. When prescribed contraceptives, only 45–65% of adolescent girls reported being appropriately counselled on potential side-effects (figure 2). In addition, only a small proportion of adolescent girls in LMICs give birth in a hospital, ranging from 18% in west and central Africa to 74% in eastern Europe and central Asia (figure 2). These findings are concerning because adolescent girls are at higher risk of complications than are older women. As well as adolescent girls, adolescent boys have been neglected in the areas of sexual and reproductive health and parenthood.61, 62

Figure 2.

Quality of reproductive health services for adolescent girls (aged 13–19 years) by region

Data taken from the latest Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 58 countries between 2010 and 2018.12 Country-level estimates are weighted using individual survey weights and regional averages are weighted according to each country's weighted sample size. Countries, survey years, and regional classification are available in the appendix (pp 4–10). *Proportion of adolescent girls who were informed about potential side-effects when first prescribed the modern contraceptive method they were using. In each country in eastern Europe and central Asia, the surveys included fewer than 25 adolescent girls who obtained a modern contraceptive method; therefore, that region was not included. †Proportion of adolescent girls who had their blood pressure checked, and urine and blood taken at any point during pregnancy. ‡Proportion of adolescent girls who gave birth in a hospital according to the facility categories used in the Demographic and Health Survey. §Proportion of adolescent girls who had any health checkup by a health provider (ie, by asking questions or examining them) after giving birth in any facility before discharge.

Health system quality for children and adolescents: user experience, confidence, and financial burden

User experience

Positive user experience in the health system requires both respectful care and care that is person-centred, family-friendly, and easy to navigate.3 However, children and their caregivers often struggle to navigate health systems.38, 63 In eight countries (DR Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal, Senegal, and Tanzania), a quarter of caregivers bringing sick children to facilities reported problems with wait times and availability of medicines. More than 10% of caregivers had problems with the amount of explanation received from providers, their ability to discuss problems, the cleanliness and hours of operation of the facility, or the cost of the services (appendix p 12). Of note, caregivers often under-report problems due to courtesy bias and low expectations.64

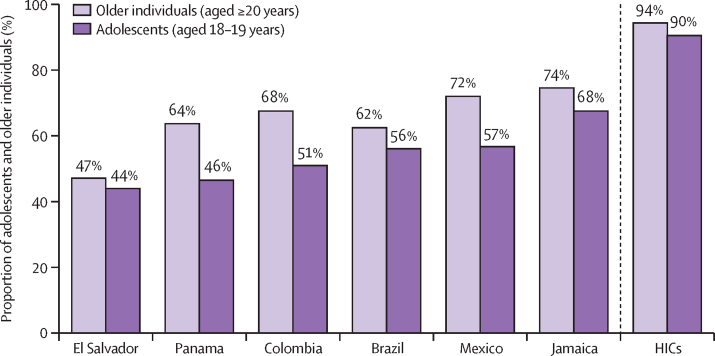

Adolescents particularly value accessible services, friendly and respectful providers, clear communication, medical competency, confidentiality, age-appropriate environment, involvement in decisions, and positive health outcomes.65 Their experience is often far from optimal, especially for adolescents who are sexually active, pregnant, unmarried, or from low-income families, and who commonly face disrespect and mistreatment.66 This situation is similar during labour and delivery, with adolescent girls at higher risk of mistreatment than older women.66, 67 In four countries (Ghana, Guinea, Myanmar, and Nigeria), more than a third of women faced verbal and physical abuse, stigma, or discrimination during labour.66, 67 In turn, mistreatment deters future care seeking.68 Furthermore, although high-quality, person-centred care requires having a regular doctor or place of care, adolescents are less likely to report having a usual source of care than are older individuals (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of adolescents and older individuals across middle-income countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and HICs who report having a regular doctor or usual place for medical care

Data in six middle-income Latin American and Caribbean countries taken from the Inter-American Development Bank survey conducted in 2013 on primary care access, use, and quality.69 Data for HICs taken from the International Health Policy Survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund across 11 HICs in 2013.70 Country-level estimates are weighted using individual survey weights. Countries, survey years, income groups, and regional classification are available in the appendix (p 11). HICs=high-income countries.

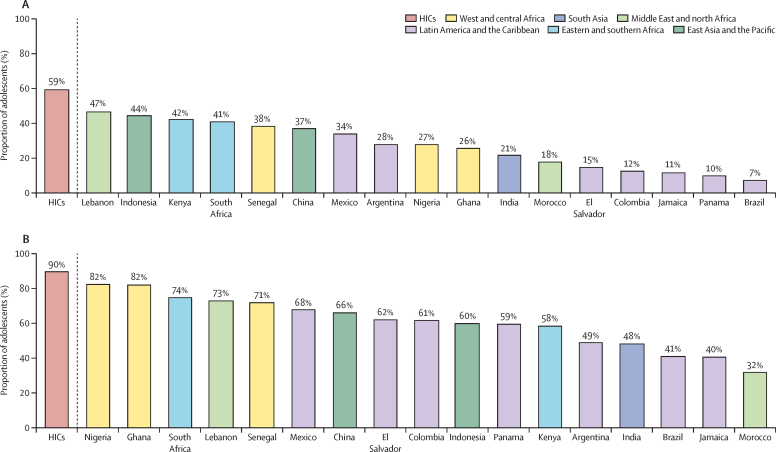

Confidence in health systems

Negative experiences with health care can result in mistrust of the health system and can reduce care seeking, retention, and adherence to treatment.3 Across 17 LMICs, between 7% and 47% of adolescent respondents agreed that their health system worked well and that only minor changes were needed to improve it, compared with 59% of adolescents across 11 HICs (figure 4A).63 Compared with adolescents in HICs, far fewer adolescents in LMICs reported being somewhat or very confident in their ability to receive the care they needed from their health system (figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Endorsement and confidence in health systems among adolescents (aged 18–19 years) in 17 LMICs and 11 HICs

Proportion of adolescents who agreed that their health system worked pretty well and that only minor changes were needed (A) and who were confident that they could get the care they needed if they got sick the following day (B). Data for LMICs taken from a nationally representative survey conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank on primary care access, use, and quality across five middle-income Latin American and Caribbean countries in 201369, 70 and an internet survey conducted by The Lancet Global Health Commission on high-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era across 12 LMICs in 2017.3 Data for HICs taken from the International Health Policy Survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund across 11 HICs in 2013. Country-level estimates are weighted using individual survey weights. Countries, survey years, income groups, and regional classification are available in the appendix (p 11). HICs=high-income countries. LMICs=low-income and middle-income countries.

Preventing financial hardship

An important function of high-quality health systems is to reduce financial hardship from care seeking, including impoverishment, catastrophic spending, borrowing money with high interest rates, and household asset sales.71, 72 Removal of fee exemptions for health system users in Africa resulted in immediate increases in care use; however, in many cases, informal, drug, and transport payments still caused substantial financial hardship.73, 74, 75 Several studies have identified substantial financial harms from undergoing a caesarean section and its cost is a barrier to health care use.76, 77, 78, 79 Although insurance can reduce financial hardship, little evidence is available about its effects on children. A 2019 systematic review found that no studies had addressed the effects of health insurance on children or adolescents with chronic conditions in LMICs.80 Issues that need to be addressed in insurance design include the scope of child and adolescent services and the maximum age that adolescents can remain on parental insurance for countries with social insurance systems.

Social system performance for children and adolescents: family, community, and school

Family support programmes

Health systems alone cannot address all child and adolescent health needs. At different ages, children and adolescents might be more readily and effectively reached through other social touchpoints to improve health.

Conditional cash transfer programmes aim to improve health and wellbeing by incentivising use of essential health care, promoting nutrition, and encouraging children from low-income families to attend school. These programmes have reduced the mortality rate of children younger than 5 years and improved other health outcomes in Brazil, India, Mexico, and other countries, generally with the greatest effects in children from families with the lowest income.81, 82

Parenting support programmes aim to target risks to child health and development, while improving relationships between parents and children.83, 84 Research shows that, when delivered in the first 5 years of life, these programmes have consistent small-to-medium sized effects on cognitive, language, motor, and socioemotional development.9, 85, 86 Additionally, these programmes can enhance caregiver knowledge, improve interactions between parents and children, and reduce parental violence against children.87, 88

Community health workers (CHWs) and community groups

CHWs are community members who have received training in basic health services and who provide health education, screening and treatment of some conditions, and community mobilisation.89, 90, 91, 92 A review of care delivered by CHWs showed reductions in perinatal and neonatal mortality, as well as benefits to mental health and early childhood development.93 Studies from Africa show that CHWs might be able to treat uncomplicated cases of pneumonia, malaria, and diarrhoea.94, 95 However, the quality of care provided by CHWs, especially for more complex curative services, is variable and often low.96, 97, 98, 99, 100 For example, an evaluation in Ethiopia found that health extension workers correctly managed only 34% of children with severe illness, and that there was no effect on mortality.99 Most CHWs are women, are generally unpaid, and are often poorly supported by health systems.101

Community groups, in which community members analyse their situation and translate solutions into action, can improve maternal and neonatal health.102 A Cochrane review found that community support or women's groups reduced perinatal mortality by 12%, neonatal mortality by 16%, and early neonatal mortality by 24%, identifying improved care seeking in facilities as an important driver.93 The positive effects of women's groups depend on the existence of strong local social networks.102 Little is known about family and community approaches to foster health in middle childhood (age 5–14 years) and adolescence, despite evidence from neuroscientific and psychological research suggesting that intervening in this period can help to support healthy development.103

Schools

Education is one of the strongest determinants of health and human capital, and has intergenerational benefits.104 The longer a child spends in school, the greater their potential for health improvement. Early childhood education has large benefits on cognitive development and small benefits on socioemotional development of children.9 A study exploring the association between educational attainment and health outcomes in young people (aged 15–24 years) found major reductions in national adolescent fertility, all-cause mortality, and HIV prevalence with an increase in the number of years in school.105 These benefits were greatest in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Additionally, schools are a platform to deliver specific health programmes. School health services are provided in over 100 countries globally and include vaccination, nutrition, disease screening, treatment (eg, vision screening and mental health counselling), and referral.106, 107 There is much interest in whether school health services can overcome the challenges faced by children, and especially by adolescents, in accessing quality health services, and requires further evaluation.108

Structural improvements and innovations in health and social systems

Improving the quality of health systems can be pursued at three levels: macro (ie, system-wide), meso (ie, region, area, or community), and micro (ie, clinic, provider, or individual user). Most attempts to improve system quality in LMICs have been at the micro level; however, many of these strategies have yielded disappointing results. A large review found that job aids or new technologies for providers were ineffective, whereas training and supervision had, at best, moderate effects.109 Additionally, these programmes are difficult to scale and sustain over time. Of note, no HICs have relied on quality improvement as the primary mechanism for building high-quality health systems.

Because health systems are complex adaptive systems that require clear aims, adequate resources, and enforced prohibitions against substandard care, structural approaches (ie, macro-level and meso-level) are more promising for building high-quality systems. Macro-level approaches intervene on the social, political, economic, and organisational structures that shape the health system, whereas meso-level approaches intervene on the subnational level across regions, districts, and networks of facilities or communities. The Lancet Global Health Commission on high-quality health systems3 proposed four such approaches: governing for quality, reforms to clinical education, redesign of service delivery to maximise quality, and increased involvement of people. We present high-potential macro-level strategies in three of these areas (ie, governance, service redesign, and empowering people) to improve neonatal, child, and adolescent health across health and social sectors.

Governing for quality

Good governance is a prerequisite for high-quality health systems. Well performing health systems manifest at least two interlinked functions: learning and strong leadership and management. These functions aim to promote a culture of performance and accountability to the population and to payers, including governments and insurers.110

Leadership, management, and coordination

Effective leadership and management require clear goals for each level of the health system; health managers who are professional and competent, and health providers that are incentivised with intrinsic and extrinsic motivators. One crucial leadership decision is the degree of specialisation and competence expected of providers for infants, children, and adolescents. Increased numbers of highly competent providers—generalists and specialists alike—will be needed in the coming decades.111, 112

In particular, subnational health systems have a scarcity of managers with data, analytical, and planning capacity, which inhibits priority setting and quality management. This situation is especially acute as more countries devolve health sector governance. Health system management is a specialised area that requires dedicated training.113, 114 In Ghana, management capacity in district health managers was significantly higher in high-performing districts than in low-performing districts; managers in high-performing districts had better communication, teamwork, and organisational commitment.115 In South Africa, monitoring and response units involved managers and clinicians from a cross-section of the health system to implement joint actions to improve maternal, neonatal, and child health.116 In Pakistan, optimising the nutrition and development of children across sectors required policy makers and managers to recognise and use policy windows, to have a clear and specific agenda of actions and coalitions, to seek cofinancing and shared platforms, and to integrate human resources and tracking systems.117

Health systems are often hampered by vertical projects led by multiple actors, such as governments, non-governmental organisations, donors, and researchers,118 which complicate effective management. These projects often do not have domestic budgets and supervision. Institutionalising and scaling new projects to realise health gains will require strong central leadership that demands programmatic coherence in the health system, greater decision space for district leaders, accountability mechanisms, increased stewardship by local leadership instead of external partners, and the ongoing involvement of community and district actors.

Learning health systems

High-quality health systems are learning health systems because they analyse their performance and use data to improve and innovate.119 Health systems in HICs use standardised data sources, such as national clinical registries (eg, perinatal, neonatal, paediatric, or cancer registries), audits, and mortality or morbidity reviews, to compare and improve outcomes across facilities and regions.120 Most HICs use a combination of routine and periodic data collection from multiple sources to monitor and enhance health system performance. Learning systems need individual patient data, yet most health management information systems operating in LMICs nowadays provide aggregate data only. Platforms established to track patient-level care and outcomes for HIV and immunisation programmes in many LMICs could be a useful model.121 The foundation of health system learning and accountability is a civil registration and vital statistics system, still far from complete in many countries globally.

Redesigning service delivery

Redesigning service delivery is a structural reform that rationalises the health system so that services are provided at the right level, by the right provider, and at the right time to optimise process quality and outcomes.3 This redesign can mean shifting services from one level of the health system to another or out of the health system to social platforms. Universal health coverage reforms might offer an opening for designating the correct platform for service delivery.

Service delivery redesign for neonatal health and COVID-19 service shifts

Despite increased use of facilities for childbirth, reductions in neonatal mortality and morbidity have stagnated in many LMICs.122, 123, 124 This situation might be because 30–45% of facility deliveries occur below the level of a hospital, in primary-care facilities that cannot effectively handle complications.125, 126, 127 Redesign to reduce neonatal and maternal mortality is a model in which all deliveries occur in either health-care facilities that can provide advanced obstetric and neonatal care in the case of complications (eg, caesarean section, blood transfusion, and care for sick mothers and newborn babies) or in nearby affiliated birthing facilities, while primary-care facilities provide quality antenatal, postnatal, and neonatal care. This model is the predominant approach in HICs and most middle-income countries.128, 129, 130 It is essential to develop locally appropriate models and to avoid overcrowding hospitals and unnecessary interventions, which can be done by placing birthing units that are led by midwives onsite or nearby, as in South Africa.131

Important innovations in service delivery are occurring in real time as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, including a shift from clinic visits to telehealth, the use of primary care to detect infection, and the upgrading of hospitals and health centres with intensive care capability.132, 133, 134, 135 These natural experiments need to be studied to yield insights for future health system responses to public health emergencies.136, 137

Whole-school approaches to promoting health

In addition to specific school-based health programmes, the health-promoting school framework provides a whole-school approach to strengthening the capacity of schools as a healthy setting for living.138 Whole-school approaches concurrently address health within the school curriculum, promote health through changes to social and physical environments at school, and engage with families and communities.138 Consistent with this approach, a study of 75 secondary schools in Bihar, India, found that a whole-school approach had large effects on school climate, depressive symptoms, bullying, violence perpetration and victimisation, attitudes towards gender, and knowledge of reproductive and sexual health.139

Community outreach to tackle mental health and to support nurturing care

Increasing evidence suggests that CHWs can provide mental health and social services to parents, children, and adolescents.140, 141, 142, 143 These services are frequently unavailable from nearby health facilities.143 CHWs in rural areas of HICs can provide various mental health services, including visits for pregnant women, support for parents of young children and adolescents with mental health disorders or stress management, and counselling or referral for substance misuse, domestic violence, depression, and anxiety.144 A systematic review in LMICs found that the provision of psychosocial interventions by CHWs was effective in reducing perinatal mental disorders and improving interactions between mother and infant; child cognition, development, and growth; and immunisation rates.142 Successful provision will require additional training and compensation of CHWs and the development of clear links to formal care for serious cases.145 COVID-19 and attendant school closures resulted in a surge of cases of psychological distress in children and adolescents in LMICs, leading to calls to substantially expand mental health services in and outside of the health system, including through community and digital approaches.146

Turning phones into health assistants

Health interventions can be delivered to mothers, children, and adolescents through various digital and mass communication platforms, including radio, television, mobile phones, and the internet. A systematic review of eight meta-analyses (mostly from HICs) supported the effectiveness of digital platforms to augment quality of care for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents, with child age, illness severity, and clinician outcome identified as key moderators of effect size.147

There is more evidence from LMICs on mobile health interventions. Automated telephone communication systems can improve health-related behaviours, clinical outcomes, health service use, immunisation, screening, appointment attendance, and adherence to medications and testing.148 A review of mobile health interventions in LMICs found improved rates of early and exclusive breastfeeding.149, 150

Use of digital and mobile technologies has increased over the COVID-19 pandemic.151, 152 For example, in South Africa, nearly 30 000 trained CHWs are using a mobile health platform for community screening, referral for testing, and communication of results. In Kenya, the incentive to make cashless health-care payments via mobile phone has been expanded to help prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. In Uganda, SMS-based virtual care has been used to monitor COVID-19 cases and contacts.134

Services delivered through digital technology and mobile phones need careful assessment before they are expanded, or before current care models are replaced, to identify effects on outcomes, care processes, cost, and equity, as well as both beneficial and detrimental system-wide effects (eg, reductions in needed in-person care).

Empowering families: raising the capacities and expectations of parents, children, and adolescents

A potentially large opportunity for improving child health is through encouraging families and adolescents to take a greater role in their health and to apply pressure on the health and social systems around them to improve service quality. Activated patients, defined as having “the skills and confidence that equip patients to become actively engaged in their health care”,153 report improved health outcomes and care experiences. Activation can be hindered by a paucity of power and knowledge, and by low expectations shaped by chronic exposure to low-quality health systems.154

Building parental capacities to care for children from the earliest years of life

The nurturing care framework promotes multi-input interventions, comprising health, nutrition, responsive caregiving, safety and security, and early learning, delivered by or in coordination with health services.155 Parenting interventions can improve the nurturing environment, which in turn boosts children's cognitive and socioemotional development. These interventions have been effectively delivered via community health services through home visits and parenting groups, and in primary health services.86, 156, 157, 158, 159 However, to date, family-based programmes for children have exclusively focused on mothers and overlooked fathers as parents and partners.160 Engaging with and supporting fathers can empower families to optimally care for and promote child health, nutrition, and development (panel). Similarly, more attention is warranted in LMICs to build parental skills in promoting adolescent wellbeing.

Panel. Engaging fathers to empower families and optimise child health and wellbeing.

In the past 5 years, several innovative interventions have shown the effectiveness and promise of engaging fathers for improving caregiving practices and early child outcomes within health and social systems.

First, Doyle and colleagues161 investigated the effects of a community group-based intervention in Rwanda, which engaged fathers and their respective partners with a child younger than 5 years. The intervention addressed fatherhood, communication and decision making between the couple, male engagement in maternal and child health, and violence prevention. Results from the randomised controlled trial found improvements in women's attendance of and men's accompaniment at antenatal care visits, paternal engagement in household responsibilities, relationships between couples, and reductions in paternal violence against women and children.

Second, Rempel and colleagues162 studied a community health intervention in Vietnam, which engaged couples expecting a child through prenatal group sessions at health clinics and postnatal home visits. These sessions were delivered by community health workers until infants reached age 9 months. The intervention also broadcasted weekly radio messages over community loudspeakers and included fathers' clubs to enhance peer support. Results from the quasi-experimental study found improvements in paternal support and responsiveness to maternal needs, exclusive breastfeeding duration, quality of couple relationships, and infant motor, language, and social development.

For young children facing multiple adversities, a multisector approach is needed. One of the few programmes currently delivered at scale is the Chile Crece Contigo, which targets interventions from pregnancy through the first 4 years of life in partnership with health departments, social development, and education sectors.163 Key reasons for the success of this initiative are a shared vision, high-level political leadership, and a permanent line in the national budget. An evaluation of this cost-effective programme reported a decrease in the prevalence of developmental delay in children over 10 years. Furthermore, multisectoral and community-engaged programmes can reduce gender-based violence and help to prevent victimisation of adolescent girls.44

Engaging parents, children, and adolescents in prevention and self-management

Schools can help to build self-management skills for children and adolescents with chronic physical or mental health conditions. School-based programmes for the self-management of children with asthma reduced emergency department visits and hospital admission rates.164 Interventions promoting self-management might improve children's lung function, glycaemic control, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.165, 166, 167, 168 Self-management of HIV in adolescents might increase adherence to care; however, outcomes vary across settings.44 To date, most studies have originated in HICs, limiting generalisability to LMICs. To yield health gains, self-management interventions require coordination with existing services, a supportive local sociopolitical context, and an enabling environment.169

Empowering families to raise their expectations of health systems

A well informed population, which is engaged in the design of health systems and in providing feedback, is a vital asset in building high-quality systems.3 Families (and adolescents) with low expectations of care have reduced agency in their interactions with providers.3 Informing communities of what they should expect ahead of a visit can empower people to demand quality care. One way to empower communities is through participatory women's and youth groups.170, 171 Mobile messaging can also be effective. MomConnect, a programme established in South Africa to promote safe motherhood and a healthy pregnancy, used a two-way messaging platform in which mothers received information on patient rights, and could ask questions and provide feedback on quality of care. The programme is widely used and has improved the health system's response to the needs and expectations of expectant mothers.172, 173, 174

Conclusions

Over the past three decades, health systems in LMICs have achieved important health gains; however, as mortality rates fall and expectations rise, reforms are needed to meet the greater scope and complexity of health needs for newborn babies, children, and adolescents. Beyond health systems, a multisectoral approach is essential for and consistent with achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Accountability is central to success: both health and social systems for children should be subject to high performance standards and be responsive to their communities.

As countries look beyond 2022, the landscape of neonatal, child, and adolescent health is rapidly shifting. The clinical effects of COVID-19 on the health and wellbeing of this population, particularly in the long term, are not fully known.175 However, disruption to health services, including interruptions to preventive activities (eg, vaccination and nutritional programmes) and decreased attendance at clinical appointments, is likely to result in excess mortality and morbidity for infants, children, and adolescents, undermining hard fought gains in recent years.137, 176, 177 This situation is compounded by an economic crisis, which has led to more families falling into poverty and facing food insecurity, and by an estimated 1·5 billion children and adolescents being out of school, which can have adverse economic consequences and an increased risk of child marriage, among other concerns.

In this fourth paper of the Series, we have proposed a shift from individual-level or clinical-level approaches to macro-level reforms that span not only the health system but also other social systems. We call for stronger leadership and governance in health, education, and social systems that are jointly focused on the health needs of children and engaged in ongoing learning; a redesign of health systems to optimise quality, right-place services by competent providers rather than contacts or proximity; and multisector actions to empower families and communities to take greater charge of their health and to demand better quality from their health systems.

Supporting structural change and monitoring progress requires agile, accurate measurements and robust research into health systems. We found substantial gaps in data on the health needs of children and adolescents. Available data are not collected in a timely fashion and do not capture all critical threats to health across the life course, nor of morbidity and physical function. Without a comprehensive measurement framework for child and adolescent health and wellbeing, as well as major investments in locally collected, reliable, and disaggregated data, substantial progress will be elusive. Rigorous and generalisable research into health systems across LMICs is scarce, despite decades of investments into improving child health. More implementation science research of higher quality to study care models and the conditions required for their implementation will be essential to inform reforms and to reduce expensive mistakes.

Although the agenda outlined in this Series paper will benefit from global support, success will be foremost determined by high-level domestic political commitment and investment. The focus on universal health coverage and the reassessment of care models accelerated by COVID-19 provides an opportunity to think anew about what it will take to change the futures of children today.

For the Optimising Child and Adolescent Health and Development Series see www.lancet.com/series/optimising-child-adolescent-health

Declaration of interests

ZAB reports grants from International Development Research Centre, UNICEF, WHO, The Rockefeller Foundation, and the Institute of International Education, during the conduct of the study. TZ reports grants from International Development Research Centre, UNICEF, WHO, The Rockefeller Foundation, and the Institute of International Education, during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

There was no funding source for this study.

Editorial note: the Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributors

MEK, TPL, and CA designed the study and planned the data analyses. MEK, TPL, and CA verified the underlying data and CA conducted the analyses. All authors participated in the conceptualisation and drafting of the original manuscript, reviewed and edited subsequent drafts, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018;392:2203–2212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruk ME, Freedman LP, Anglin GA, Waldman RJ. Rebuilding health systems to improve health and promote statebuilding in post-conflict countries: a theoretical framework and research agenda. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1196–e1252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black RE, Liu L, Hartwig FP, et al. Health and development from preconception to 20 years of age and human capital. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02533-2. published online April 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victora CG, Hartwig FP, Vidaletti LP, et al. Effects of early-life poverty on health and human capital in children and adolescents: analyses of national surveys and birth cohort studies in LMICs. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02716-1. published online April 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaivada T, Lassi ZS, Irfan O, et al. What can work and how? An overview of evidence-based interventions and delivery strategies to support health and human development from before conception to 20 years. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02725-2. published online April 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387:587–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LC, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, et al. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet. 2017;389:91–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter LM, Daelmans B, Lombardi J, et al. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet. 2017;389:103–118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1725–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Demographic and Health Surveys Program Available datasets. https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

- 13.UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys Surveys. https://mics.unicef.org/surveys

- 14.Abegunde D, Kabo IA, Sambisa W, et al. Availability, utilization, and quality of emergency obstetric care services in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wichaidit W, Alam MU, Halder AK, Unicomb L, Hamer DH, Ram PK. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric and newborn care in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:298–306. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mpunga Mukendi D, Chenge F, Mapatano MA, Criel B, Wembodinga G. Distribution and quality of emergency obstetric care service delivery in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: it is time to improve regulatory mechanisms. Reprod Health. 2019;16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afulani PA. Determinants of stillbirths in Ghana: does quality of antenatal care matter? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:132. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsenault C, Jordan K, Lee D, et al. Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 national household surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1186–e1195. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2019. Survive and thrive: transforming care for every small and sick newborn. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy GAV, Gathara D, Mwachiro J, Abuya N, Aluvaala J, English M. Effective coverage of essential inpatient care for small and sick newborns in a high mortality urban setting: a cross-sectional study in Nairobi City County, Kenya. BMC Med. 2018;16:72. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aluvaala J, Nyamai R, Were F, et al. Assessment of neonatal care in clinical training facilities in Kenya. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:42–47. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gathara D, Opiyo N, Wagai J, et al. Quality of hospital care for sick newborns and severely malnourished children in Kenya: a two-year descriptive study in 8 hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:307. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gathara D, Serem G, Murphy GAV, et al. Missed nursing care in newborn units: a cross-sectional direct observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:19–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy GAV, Gathara D, Abuya N, et al. What capacity exists to provide essential inpatient care to small and sick newborns in a high mortality urban setting? A cross-sectional study in Nairobi City County, Kenya. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Wertlieb D, et al. Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1100–e1121. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30309-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu C, Black MM, Richter LM. Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: an estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e916–e922. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shonkoff JP, Richter L, van der Gaag J, Bhutta ZA. An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e460–e472. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Haan M, Wyatt JS, Roth S, Vargha-Khadem F, Gadian D, Mishkin M. Brain and cognitive-behavioural development after asphyxia at term birth. Dev Sci. 2006;9:350–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton GC, Olsson CA, Skirbekk V, et al. Adolescence and the next generation. Nature. 2018;554:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nature25759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ertem IO, Krishnamurthy V, Mulaudzi MC, et al. Similarities and differences in child development from birth to age 3 years by sex and across four countries: a cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e279–e291. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gladstone M, Abubakar A, Idro R, Langfitt J, Newton CR. Measuring neurodevelopment in low-resource settings. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1:258–259. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392:1553–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macharia PM, Joseph NK, Okiro EA. A vulnerability index for COVID-19: spatial analysis at the subnational level in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. UNICEF Progress and challenges with achieving universal immunization coverage: 2019 WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/who-immuniz.pdf

- 36.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Mbaruku GM, Leslie HH. Content of care in 15,000 sick child consultations in nine lower-income countries. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:2084–2098. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayieko P, Ogero M, Makone B, et al. Characteristics of admissions and variations in the use of basic investigations, treatments and outcomes in Kenyan hospitals within a new Clinical Information Network. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:223–229. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willcox ML, Kumbakumba E, Diallo D, et al. Circumstances of child deaths in Mali and Uganda: a community-based confidential enquiry. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e691–e702. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. The World Bank . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. World report on disability 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivara FP. Prevention of death and disability from injuries to children and adolescents. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19:226–230. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.686919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo BJ, Vaca SA-O, Vissoci JRN, et al. A prospective neurosurgical registry evaluating the clinical care of traumatic brain injury patients presenting to Mulago National Referral Hospital in Uganda. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivara FP. Prevention of death and disability from injuries to children and adolescents. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19:226–230. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.686919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bowman KG, Jovic G, Rangel S, Berry WR, Gawande AA. Pediatric emergency and essential surgical care in Zambian hospitals: a nationwide study. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1363–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crowley T, Rohwer A. Self-management interventions for adolescents living with HIV: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:431. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campisi SC, Carducci B, Akseer N, Zasowski C, Szatmari P, Bhutta ZA. Suicidal behaviours among adolescents from 90 countries: a pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGorry PD, Goldstone SD, Parker AG, Rickwood DJ, Hickie IB. Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:559–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu C, Li Z, Patel V. Global child and adolescent mental health: the orphan of development assistance for health. PLoS Med. 2018;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Friedrich P, Alcasabas P, et al. Toward the cure of all children with cancer through collaborative efforts: pediatric oncology as a global challenge. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3065–3073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Girardi F, Atun R. Global childhood cancer survival estimates and priority-setting: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:972–983. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam CG, Howard SC, Bouffet E, Pritchard-Jones K. Science and health for all children with cancer. Science. 2019;363:1182–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cervio C, Barsotti D, Ibanez J, Paganini H, Sara Felice M, Chantada GL. Early mortality in children with advanced mature B-cell malignancies in a middle-income country. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e266–e270. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31826226b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaytan-Morales F, Alejo-Gonzalez F, Reyes-Lopez A, et al. Pediatric mature B-cell NHL, early referral and supportive care problems in a developing country. Hematology. 2019;24:79–83. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2018.1510087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howard SC, Zaidi A, Cao X, et al. The My Child Matters programme: effect of public-private partnerships on paediatric cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e252–e266. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Day S, Hollis R, Challinor J, Bevilacqua G, Bosomprah E. Baseline standards for paediatric oncology nursing care in low to middle income countries: position statement of the SIOP PODC Nursing Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:681–682. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70213-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedrich P, Lam CG, Itriago E, Perez R, Ribeiro RC, Arora RS. Magnitude of treatment abandonment in childhood cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrissey L, Lurvey M, Sullivan C, et al. Disparities in the delivery of pediatric oncology nursing care by country income classification: international survey results. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66 doi: 10.1002/pbc.27663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z, Patton G, Sabet F, Zhou Z, Subramanian SV, Lu C. Contraceptive use in adolescent girls and adult women in low- and middle-income countries. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. Lancet. 2019;393:1101–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bell DL, Breland DJ, Ott MA. Adolescent and young adult male health: a review. Pediatrics. 2013;132:535–546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jeong J. Determinants and consequences of adolescent fatherhood: a longitudinal study in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gedleh A, Lee S, Hill JA, et al. “Where does it come from?” Experiences among survivors and parents of children with retinoblastoma in Kenya. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:574–588. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roder-DeWan S, Gage AD, Hirschhorn LR, et al. Expectations of healthcare quality: a cross-sectional study of internet users in 12 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2019;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ambresin AE, Bennett K, Patton GC, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM. Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people's perspectives. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bohren MA, Mehrtash H, Fawole B, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet. 2019;394:1750–1763. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maya ET, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Dako-Gyeke P, et al. Women's perspectives of mistreatment during childbirth at health facilities in Ghana: findings from a qualitative study. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:70–87. doi: 10.1080/09688080.2018.1502020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Inter-American Development Bank Primary healthcare access, experience, and coordination in Latin America and the Caribbean 2013 (PRIMLAC) https://publications.iadb.org/en/primary-healthcare-access-experience-and-coordination-latin-america-and-caribbean-2013-primlac

- 70.The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. Nov 13, 2013. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2013/nov/2013-commonwealth-fund-international-health-policy-survey

- 71.WHO. The World Bank . World Health Organization and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (The World Bank); Geneva: 2017. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murphy A, McGowan C, McKee M, Suhrcke M, Hanson K. Coping with healthcare costs for chronic illness in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lagarde M, Palmer N. The impact of user fees on health service utilization in low- and middle-income countries: how strong is the evidence? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:839–848. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barasa EW, Ayieko P, Cleary S, English M. Out-of-pocket costs for paediatric admissions in district hospitals in Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:958–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruk ME, Mbaruku G, Rockers PC, Galea S. User fee exemptions are not enough: out-of-pocket payments for ‘free’ delivery services in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1442–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Enabudoso EJ, Ezeanochie MC, Olagbuji BN. Perception and attitude of women with previous caesarean section towards repeat caesarean delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:1212–1214. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.565833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ushie BA, Udoh EE, Ajayi AI. Examining inequalities in access to delivery by caesarean section in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Borrescio-Higa F, Valdés N. Publicly insured caesarean sections in private hospitals: a repeated cross-sectional analysis in Chile. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singh P, Hashmi G, Swain PK. High prevalence of cesarean section births in private sector health facilities- analysis of district level household survey-4 (DLHS-4) of India. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:613. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van Hees SGM, O'Fallon T, Hofker M, et al. Leaving no one behind? Social inclusion of health insurance in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1040-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CA, Paes-Sousa R, Barreto ML. Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet. 2013;382:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cooper JE, Benmarhnia T, Koski A, King NB. Cash transfer programs have differential effects on health: a review of the literature from low and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2020;247 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nahar B, Hossain MI, Hamadani JD, et al. Effects of a community-based approach of food and psychosocial stimulation on growth and development of severely malnourished children in Bangladesh: a randomised trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:701–709. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Singla DR, Kumbakumba E, Aboud FE. Effects of a parenting intervention to address maternal psychological wellbeing and child development and growth in rural Uganda: a community-based, cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e458–e469. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aboud FE, Yousafzai AK. Global health and development in early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:433–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeong J, Franchett EE, Ramos de Oliveira CV, Rehmani K, Yousafzai AK. Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jeong J, Pitchik HO, Yousafzai AK. Stimulation interventions and parenting in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ward CL, Wessels IM, Lachman JM, et al. Parenting for lifelong health for young children: a randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:503–512. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gogia S, Ramji S, Gupta P, et al. Community based newborn care: a systematic review and metaanalysis of evidence: UNICEF-PHFI series on newborn and child health, India. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gogia S, Sachdev HP. Home-based neonatal care by community health workers for preventing mortality in neonates in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Perinatol. 2016;36(suppl 1):S55–S73. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:658–666B. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.069369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, et al. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1736–1746. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007754.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Amouzou A, Morris S, Moulton LH, Mukanga D. Assessing the impact of integrated community case management (iCCM) programs on child mortality: review of early results and lessons learned in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health. 2014;4 doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.020411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Christopher JB, Le May A, Lewin S, Ross DA. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: a systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amouzou A, Kanyuka M, Hazel E, et al. Independent evaluation of the integrated community case management of childhood illness strategy in Malawi using a national evaluation platform design. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:574–583. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carvajal-Vélez L, Amouzou A, Perin J, et al. Diarrhea management in children under five in sub-Saharan Africa: does the source of care matter? A Countdown analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:830. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gilroy KE, Callaghan-Koru JA, Cardemil CV, et al. Quality of sick child care delivered by health surveillance assistants in Malawi. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:573–585. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miller NP, Amouzou A, Tafesse M, et al. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:424–434. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Teklehaimanot HD, Teklehaimanot A, Tedella AA, Abdella M. Use of balanced scorecard methodology for performance measurement of the Health Extension Program in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:1157–1169. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maes K, Closser S, Tesfaye Y, Abesha R. Psychosocial distress among unpaid community health workers in rural Ethiopia: comparing leaders in Ethiopia's Women's Development Army to their peers. Soc Sci Med. 2019;230:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. WHO recommendation on community mobilization through facilitated participatory learning and action cycles with women's groups for maternal and newborn health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]