Key Points

Question

What are the prevalence and common sources of workplace mistreatment of physicians, and is there an association between workplace mistreatment and occupational well-being?

Findings

A survey of 1505 physicians conducted from September to October 2020 found that 23.4% had experienced mistreatment in the last year, with patients and visitors as the most frequent source of mistreatment. Mistreatment was associated with higher levels of occupational distress, whereas the perception that protective workplace systems exist was associated with lower levels of occupational distress.

Meaning

These findings suggest that systems that prevent workplace mistreatment may improve physicians’ occupational well-being.

This survey study evaluates the prevalence and sources of mistreatment among physicians and associations between mistreatment, occupational well-being, and physicians’ perceptions of protective workplace systems.

Abstract

Importance

Reducing physician occupational distress requires understanding workplace mistreatment, its relationship to occupational well-being, and how mistreatment differentially impacts physicians of diverse identities.

Objectives

To assess the prevalence and sources of mistreatment among physicians and associations between mistreatment, occupational well-being, and physicians’ perceptions of protective workplace systems.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study was administered in September and October 2020 to physicians at a large academic medical center. Statistical analysis was performed from May 2021 to February 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary measures were the Professional Fulfillment Index, a measure of intent to leave, and the Mistreatment, Protection, and Respect Measure (MPR). Main outcomes were the prevalence and sources of mistreatment. Secondary outcomes were the associations of mistreatment and perceptions of protective workplace systems with occupational well-being.

Results

Of 1909 medical staff invited, 1505 (78.8%) completed the survey. Among respondents, 735 (48.8%) were women, 627 (47.1%) were men, and 143 (9.5%) did not share gender identity or chose “other”; 12 (0.8%) identified as African American or Black, 392 (26%) as Asian, 10 (0.7%) as multiracial, 736 (48.9%) as White, 63 (4.2%) as other, and 292 (19.4%) did not share race or ethnicity. Of the 1397 respondents who answered mistreatment questions, 327 (23.4%) reported experiencing mistreatment in the last 12 months. Patients and visitors were the most common source of mistreatment, reported by 232 physicians (16.6%). Women were more than twice as likely as men to experience mistreatment (31% [224 women] vs 15% [92 men]). On a scale of 0 to 10, mistreatment was associated with a 1.13 point increase in burnout (95% CI, 0.89 to 1.36), a 0.99-point decrease in professional fulfillment (95% CI, −1.24 to −0.73), and 129% higher odds of moderate or greater intent to leave (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.75 to 2.99). When compared with a perception that protective workplace systems are in place “to a very great extent,” a perception that there are no protective workplace systems was associated with a 2.41-point increase in burnout (95% CI, 1.80 to 3.02), a 2.81-point lower professional fulfillment score (95% CI, −3.44 to −2.18), and 711% higher odds of intending to leave (odds ratio, 8.11; 95% CI, 3.67 to 18.35).

Conclusions and Relevance

This survey study found that mistreatment was common among physicians, varied by gender, and was associated with occupational distress. Patients and visitors were the most frequent source, and perceptions of protective workplace systems were associated with better occupational well-being. These findings suggest that health care organizations should prioritize reducing workplace mistreatment.

Introduction

Studies of mistreatment in medicine have largely focused on mistreatment among trainees, with less attention on practicing physicians.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Among trainees, mistreatment is common and varies by gender and race; in a national survey of general surgery residents, almost two-thirds of women reported experiencing gender-based harassment, compared with 10% of men.4 Mistreatment of physicians of color may be more common, although the literature is sparse. Limited data suggest that workplace mistreatment experiences are associated with increased burnout,4 worse job performance,8 and depression.1

Sources of mistreatment in health care include colleagues, patients and visitors, and for trainees, supervising physicians.4,6,9,10 However, few studies have directly addressed mistreatment by patients and visitors.

We explored the prevalence and sources of mistreatment among physicians at a large academic medical center and assessed how mistreatment experiences vary by gender and race. We also studied the association of experiencing mistreatment with burnout, professional fulfillment, and intent to leave the organization. Finally, we evaluated the hypothesis that physicians’ perceptions of protective workplace systems are associated with occupational well-being.

Methods

Survey Administration

In September and October of 2020, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, conducted an administrative survey through an independent third-party survey administrator to inform organizational efforts to improve professional fulfillment and wellness among clinical faculty. All Stanford-employed members of the clinically active medical staff with an appointment of at least 0.5 full-time equivalent were invited to participate via email. Up to 5 reminders were sent to nonrespondents. The 3 departments with the highest response rates received $50 per respondent. All respondents had MD or DO degrees, with the exception of 20 clinical psychologists. To simplify, we refer to the medical staff as physicians from this point on.

Participation was voluntary. The response rate of complete and partially completed surveys was determined using the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.11,12 The Stanford University institutional review board deemed this study exempt and informed consent was not needed because the study involved retrospective analysis of administratively collected deidentified data.

Survey Measures

Occupational Well-being

The survey included the Professional Fulfillment Index. This index is a measurement of burnout and professional fulfillment demonstrated to have good reliability and construct validity, along with a standardized question about intent to leave within the next 2 years, described elsewhere.13,14,15

Measures of Mistreatment and Protections From Mistreatment

The Mistreatment, Protection, and Respect (MPR) Measure is a 7-item measure assessing experiences of different types of mistreatment, together with the sources of mistreatment, as well as the perception of protective workplace systems. The MPR was created by the authors by conducting literature searches for relevant theoretical frameworks and related measures. The survey was then reviewed for face and content validity by 7 researchers with extensive experience in Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) in the health care setting. After iterative feedback and improvement, the scale was pilot tested with a diverse sample of 16 clinicians working in the area of DEI (additional details in eAppendix 1 of the Supplement). Respondents answered yes or no to the question: “Have you experienced the following at work in the last 12 months and if so from whom?” for 3 categories of mistreatment: sexual harassment or abuse; verbal mistreatment or abuse; physical intimidation, violence, or abuse. Possible sources included: patient/family/visitors; colleague; nurse; other staff; and/or leadership. Participants could choose all that apply.

The MPR also includes 2 questions related to protective factors, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (not at all = 0; to a very great extent = 4): “There are good systems in place to ensure that I am treated with respect and dignity” and “Bystanders speak up or intervene if someone is mistreated.” The MPR also includes 2 questions not addressed in this study. (See the eAppendix 1 in the Supplement for a description of the methodology used to develop the MPR measure, and see eAppendix 2 in the Supplement for the full text of the measure.)

Demographics

Demographic characteristics were assessed including self-reported gender, race, age, and specialty. Respondents were asked to choose one gender from options: female, male, self-defined, prefer not to answer. Respondents selected one or more race categories from these options: Asian, Black, White, Other, prefer not to answer.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported to summarize respondent characteristics. Percentages were reported for categorical variables. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables. Professional fulfillment and burnout were scored using a published approach and transformed to a 10-point scale.16 Differences in responses to the mistreatment questions among gender and racial groups were examined using a Pearson χ2 test. Associations between mistreatment and burnout and mistreatment and professional fulfillment were examined using linear regression models. The difference in burnout and professional fulfillment by mistreatment experience was further examined by multiple linear regression models where we added responses to the questions assessing perceptions that “bystanders speak up or intervene” and “there are good systems in place to ensure that I am treated with respect and dignity.” To assess standardized mean difference (SMD) effect size associations with independent variables, multiple linear regression models were repeated with standardized (z score) transformed dependent variables for both burnout and professional fulfillment. To examine the association between intent to leave and mistreatment experience, we used univariable logistic regression, and then used multiple logistic regression with responses to questions assessing perceptions that “bystanders speak up or intervene” and “there are good systems in place to ensure that I am treated with respect and dignity.” All analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) from May 2021 to February 2022. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 1909 physicians invited, 1505 (78.8%) responded, including 735 women (48.8%), 627 men (41.7%), and 143 (9.5%) whose gender either was not disclosed or who identified as neither male nor female (<5 respondents); 12 (0.8%) identified as African American or Black, 392 (26%) as Asian, 10 (0.7%) as multiracial, 736 (48.9%) as White, 63 (4.2%) as other, and 292 (19.4%) did not share race or ethnicity (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Respondents.

| Characteristic | Respondents, No. (%) (N = 1505) |

|---|---|

| Department | |

| Anesthesiology | 160 (10.6) |

| Cardiothoracic surgery | 14 (0.9) |

| Dermatology | 37 (2.5) |

| Emergency medicine | 71 (4.7) |

| Medicine | 305 (20.3) |

| Neurology | 67 (4.5) |

| Neurosurgery | 16 (1.1) |

| OBGYN | 36 (2.4) |

| Ophthalmology | 28 (1.9) |

| Orthopaedic surgery | 58 (3.9) |

| Otolaryngology | 36 (2.4) |

| Pathology | 56 (3.7) |

| Pediatrics | 301 (20.0) |

| Psychiatry | 102 (6.8) |

| Radiation oncology | 37 (2.5) |

| Radiology | 87 (5.8) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (0.2) |

| Surgery | 74 (4.9) |

| Urology | 17 (1.1) |

| Burnout, score on 0-10 scale, mean (SD)a | 3.04 (1.96) |

| Professional fulfillment, score on 0-10 scale, mean (SD)b | 6.53 (2.09) |

| Intent to leave | |

| No | 1047 (69.6) |

| Yes | 366 (24.3) |

| Missing | 92 (6.1) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 735 (48.8) |

| Male | 627 (41.7) |

| Missingc | 143 (9.5) |

| Race | |

| African American or Black | 12 (0.8) |

| Asian | 392 (26.0) |

| Multiracial | 10 (0.7) |

| White | 736 (48.9) |

| Otherd | 63 (4.2) |

| Missing | 292 (19.4) |

| Protective systems | |

| Not at all | 62 (4.1) |

| To a small extent | 153 (10.2) |

| To a moderate extent | 383 (25.4) |

| To a great extent | 508 (33.8) |

| To a very great extent | 278 (18.5) |

| Missing | 121 (8.0) |

| Bystanders speak up | |

| Not at all | 100 (6.6) |

| To a small extent | 269 (17.9) |

| To a moderate extent | 453 (30.1) |

| To a great extent | 369 (24.5) |

| To a very great extent | 160 (10.6) |

| Missing | 154 (10.2) |

| Experienced mistreatmente | |

| No | 1070 (71.1) |

| Yes | 327 (21.7) |

| Missing | 108 (7.2) |

Higher scores unfavorable.

Higher scores favorable.

Missing gender includes respondents who elected not to identify their gender and less than 5 respondents who self-identified as a less-represented gender.

Respondents were given the option to select “other” in describing their race.

Includes any respondent who reported experiencing at least 1 form of mistreatment (sexual, verbal, or physical).

Of the physicians who responded to questions on mistreatment, 327 of 1397 (23.4%) reported experiencing workplace mistreatment in the past 12 months (Table 2). Mistreatment by patients and visitors was reported by 232 physicians (16.6%), representing the most common source of mistreatment at 70.9% of all mistreatment events. Other physicians were the second most common source of mistreatment, reported by 7.1% of respondents. Verbal mistreatment was the most frequent form of mistreatment, reported by 298 respondents (21.5%), followed by sexual harassment (74 respondents [5.4%]), and physical intimidation or abuse (72 respondents [5.2%]).

Table 2. Type and Source of Mistreatmenta.

| Type of mistreatment | No. | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any source | Patient/family/visitors | Colleague | Nurse | Other staff | Leadership | ||

| Sexual harassment or abuse | 1384 | 75 (5.4) | 56 (4.0) | 21 (1.5) | 1 (0.1) | 8 (0.6) | 6 (0.4) |

| Verbal mistreatment or abuse | 1386 | 298 (21.5) | 203 (14.6) | 83 (6.0) | 15 (1.1) | 21 (1.5) | 41 (3.0) |

| Physical intimidation, violence, or abuse | 1394 | 72 (5.2) | 65 (4.7) | 5 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Any of above forms of mistreatmentb | 1397 | 327 (23.4) | 232 (16.6) | 99 (7.1) | 17 (1.2) | 29 (2.1) | 43 (3.1) |

Percentages in each column or row may add up to more than 100%, as individual respondents may have endorsed mistreatment in multiple categories and/or from multiple sources.

Includes any respondent who reported experiencing at least 1 form of mistreatment (sexual, verbal, or physical).

Table 3 reports the prevalence of mistreatment experiences by gender and race. Mistreatment experiences differed significantly by gender, with a greater proportion of women (63 of 715 [8.8%]) than men (9 of 609 [1.5%]) reporting experiencing sexual harassment (P < .001; χ21 = 32.98). Women were also more likely (201 of 717 [28.0%]) than men (87 of 609 [14.3%]) to report experiencing verbal mistreatment (P < .001; χ21 = 35.80). Overall, 224 women (31.0%) experienced 1 or more forms of mistreatment compared with 92 men (15.0%) (P < .001; χ21 = 46.61).

Table 3. Experience of Mistreatment by Gender and Race.

| Type of mistreatment | Gender | Race | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | ||||||

| Female | Male | Black | Asian | Multiracial | White | Other | |||

| Sexual harassment or abuse | |||||||||

| No | 652 (91.2) | 600 (98.5) | <.001 | 11 (91.7) | 366 (95.8) | 9 (90.0) | 683 (95.1) | 54 (87.1) | .06 |

| Yes | 63 (8.8) | 9 (1.5) | 1 (8.3) | 16 (4.2) | 1 (10.0) | 35 (4.9) | 8 (12.9) | ||

| Verbal mistreatment or abuse | |||||||||

| No | 516 (72.0) | 522 (85.7) | <.001 | 6 (50.0) | 297 (77.7) | 5 (55.6) | 587 (81.4) | 42 (68.9) | .003 |

| Yes | 201 (28.0) | 87 (14.3) | 6 (50.0) | 85 (22.3) | 4 (44.4) | 134 (18.6) | 19 (31.1) | ||

| Physical intimidation, violence, or abuse | |||||||||

| No | 675 (93.9) | 590 (95.9) | .12 | 10 (83.3) | 366 (95.3) | 8 (80.0) | 689 (95.3) | 55 (88.7) | .01 |

| Yes | 44 (6.1) | 25 (4.1) | 2 (16.7) | 18 (4.7) | 2 (20.0) | 34 (4.7) | 7 (11.3) | ||

| Any of above forms of mistreatment | |||||||||

| No | 498 (69.0) | 523 (85.0) | <.001 | 6 (50.0) | 295 (76.4) | 5 (50.0) | 572 (79.0) | 42 (67.7) | .008 |

| Yes | 224 (31.0) | 92 (15.0) | 6 (50.0) | 91 (23.6) | 5 (50.0) | 152 (21.0) | 20 (32.3) | ||

Statistically significant disparities in workplace mistreatment were present across racial groups (P = .008; χ24 = 13.79) (Table 3). Differences by race were demonstrated in (1) verbal mistreatment (P = .003; χ24 = 15.78), and (2) physical intimidation or violence (P = .01; χ24 = 12.65). These analyses comparing distribution of mistreatment across racial groups do not attempt to contrast specific pairs of racial categories for statistically significant differences. However, descriptive mistreatment data for racial subgroups is summarized below.

Multiracial and Black physicians were more likely than White and Asian physicians to report experiencing at least 1 form of mistreatment. Experiencing verbal mistreatment was highest among Black physicians (6 of 12 [50%]) and lowest among White physicians (134 of 721 [18.6%]). Being subjected to physical intimidation or abuse was highest among multiracial physicians (2 of 10 [20%]) and lowest among White (34 of 723 [4.7%]) and Asian (18 of 384 [4.7%]) physicians. Experiencing any type of mistreatment was most common among multiracial physicians (5 of 10 [50.0%]) and Black physicians (6 of 12 [50.0%], and least common among White physicians (152 of 724 [21.0%]). A subset analysis comparing people who did not provide gender or race and ethnicity data with those who did yielded no significant differences in reports of mistreatment (eTable1 in the Supplement).

Results of Regression Analyses

Regression analyses (Table 4) found that having experienced any type of workplace mistreatment was associated with a 1.13-point increase in burnout (scale range: 0 to 10; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.36; P < .001) and a 0.99-point (scale range: 0 to 10) decrease in professional fulfillment (95% CI, −1.24 to −0.73; P < .001). Expressed in terms of standardized mean difference, having experienced any type of workplace mistreatment was associated with a 0.57 standard deviation unit increase in burnout score (95% CI, 0.45 to 0.70) and a 0.47 standard deviation unit decrease in the professional fulfillment (95% CI, −0.59 to −0.35) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The association between burnout and mistreatment remained statistically significant after adjusting for the perception that bystanders intervene and that protective workplace systems are in place; however, the association with professional fulfillment of workplace mistreatment was no longer significant after adjusting for the perception that bystanders intervene and the perception that protective workplace systems are in place.

Table 4. Parameter Estimates From Regression Analyses of Associations of Mistreatment and Protective Factors With Burnout, Professional Fulfillment, and Intent to Leave.

| Independent variables | Linear regression, β (95% CI) | Model 3a (Intent to Leave) logistic regression, OR (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a (burnout)a | Model 2a (PF)b | ||

| Mistreatment | |||

| No | [Reference] | [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.36) | −0.99 (−1.24 to −0.73) | 2.29 (1.75 to 2.99) |

| Missing | 0.36 (−0.07 to 0.79) | −0.12 (−0.56 to 0.33) | 1.73 (0.83 to 3.43) |

| Abuse | |||

| No | [Reference] | [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.52 (0.29 to 0.76) | −0.20 (−0.45 to 0.04) | 1.45 (1.08 to 1.94) |

| Missing | 0.24 (−0.32 to 0.81) | −0.30 (−0.28 to 0.88) | 1.73 (0.75 to 3.83) |

| Protective systems | |||

| To a very great extent | [Reference] | [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| To a great extent | 0.76 (0.44 to 1.08) | −0.88 (−1.21 to −0.55) | 1.93 (1.16 to 3.3) |

| To a moderate extent | 1.30 (0.94 to 1.67) | −1.60 (−1.98 to −1.22) | 2.76 (1.58 to 4.95) |

| To a small extent | 1.71 (1.24 to 2.17) | −2.33 (−2.82 to −1.85) | 4.65 (2.43 to 9.11) |

| Not at all | 2.41 (1.80 to 3.02) | −2.81 (−3.44 to −2.18) | 8.11 (3.67 to 18.35) |

| Missing | 0.71 (0.04 to 1.38) | −0.98 (−1.67 to −0.28) | 2.98 (1.14 to 7.63) |

| Bystanders speak up | |||

| To a very great extent | [Reference] | [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| To a great extent | 0.30 (−0.09 to 0.69) | −0.34 (−0.74 to 0.07) | 0.86 (0.47 to 1.59) |

| To a moderate extent | 0.32 (−0.09 to 0.73) | −0.37 (−0.80 to 0.06) | 0.78 (0.41 to 1.48) |

| To a small extent | 0.27 (−0.19 to 0.74) | −0.47 (−0.95 to 0.01) | 0.9 (0.45 to 1.78) |

| Not at all | 1.08 (0.50 to 1.65) | −1.25 (−1.85 to −0.65) | 1.53 (0.7 to 3.38) |

| Missing | 0.58 (−0.03 to 1.19) | −0.92 (−1.55 to −0.29) | 0.62 (0.25 to 1.5) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PF, professional fulfillment.

Data are for 1458 participants; R2 = 0.06; F2,1455 = 43.42.

Data are for 1479 participants; R2 = 0.04; F2,1476 = 29.18.

Data are for 1413 participants; Akaike information criterion = 1586.2.

In multivariable models (Table 4), decreased perception that protective workplace systems are in place was associated with higher levels of burnout and lower levels of professional fulfillment. Compared with the highest rating of protective workplace systems (systems in place “to a very great extent”), the lowest rating (systems in place “not at all”) was associated with a 2.41-point increase in burnout (95% CI, 1.80 to 3.02; P < .001) and a 2.81-point decrease in professional fulfillment (95% CI, −3.44 to −2.18; P < .001). Compared with the highest rating of bystander intervention (bystanders intervene “to a very great extent”), the lowest rating (bystanders intervene “not at all”) was associated with a 1.08-point increase in burnout (95% CI, 0.50 to 1.65; P = .002) and a 1.25-point decrease in professional fulfillment (95% CI, −1.85 to −0.65; P < .001). Smaller differences in perception that bystanders intervene did not demonstrate significant association with either burnout or professional fulfillment.

Any form of mistreatment was associated with 129% higher odds of reporting moderate or greater intent to leave within 2 years (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.75 to 2.99; P < .001) (Table 4). The association of mistreatment with intent to leave remained statistically significant after adjusting for the perception that bystanders intervene and that protective workplace systems are in place. In the multivariable model, decreased perception that protective workplace systems are in place was associated with greater intent to leave. Compared with the highest rating of protective workplace systems (systems in place “to a very great extent”), the lowest rating (systems in place “not at all”) was associated with 711% higher odds of moderate or greater intent to leave (odds ratio, 8.11; 95% CI, 3.67 to 18.35; P < .001). Differences in perception that bystanders intervene did not demonstrate significant association with intent to leave.

Discussion

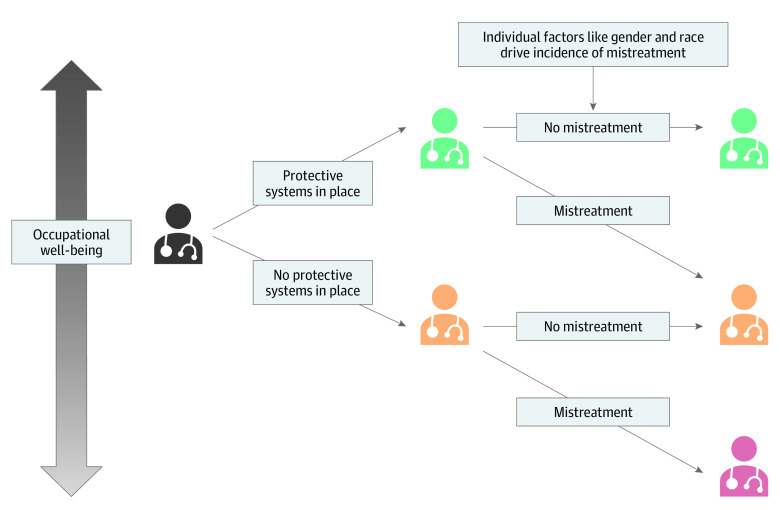

This survey study found a high prevalence of mistreatment among attending physicians, particularly women. Our study builds on existing literature on physician mistreatment in several ways. Although it has been reported that medical students and residents experience frequent mistreatment,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,10 to date there has been sparse corresponding data on the prevalence of sources of mistreatment for practicing physicians.17,18,19,20 We found that mistreatment was most likely to originate from patients and visitors, underscoring the need to address this less studied source of mistreatment. Finally, we found a strong association between mistreatment and worse occupational well-being, including increased burnout, reduced professional fulfillment, and higher reported intent to leave the organization. Conversely, having systems in place that protect physicians from mistreatment is associated with increased occupational well-being, both for those who experienced mistreatment and those who did not (Figure). To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between the perception of protective workplace systems and occupational well-being for physicians.

Figure. Conceptual Model of Association of Protective Workplace System and Mistreatment With Physician Occupational Well-being.

Our finding that patients and visitors were the most frequent perpetrators of mistreatment toward physicians has important implications for physician well-being. Organizational interventions that address mistreatment in the workplace, such as bystander training and implicit bias training, have typically focused on mistreatment originating within the organization (ie, coworkers),21 vs mistreatment by patients and visitors. An employee-centered approach is less likely to influence harmful behavior by patients and visitors. Extant efforts to reduce mistreatment perpetrated by patients and visitors include published expectations of patient behavior and procedures for dismissing (ie, refusing to serve) abusive patients.22 However, it is unclear how effective these systems are in reducing the incidence of misbehavior. Addressing patients and visitors as sources of mistreatment will require a thoughtful approach that acknowledges multiple factors, including the power differential inherent in the physician-patient relationship, patients’ experiences of bias and mistreatment in the health care setting, and the primacy of patient experience metrics as a business imperative for health care organizations.

In our sample, there were disparities in the experience of mistreatment by gender, with women experiencing mistreatment at higher rates than men. Women were more likely to experience any form of mistreatment, as well as more likely to experience sexual harassment and verbal mistreatment. Previous studies have found higher rates of occupational distress among women physicians.23,24,25,26 These differences have been attributed to inequities in domestic responsibilities25 and to differences in the work environment.27,28,29,30 The increased rate of mistreatment experiences we found may be 1 modifiable factor in the work environment that contributes to the gender disparity in occupational well-being.

Prevalence of mistreatment also differed by race, with higher rates among the small number of physicians of color and those identifying as multiracial. Future research involving larger numbers of these racial groups are needed to assess replicability and significance of these observations. Nevertheless, these observations align with previous studies showing disparities in the experience of mistreatment by race and ethnicity among medical students and residents as well as numerous personal accounts of mistreatment that have been shared by physicians from underrepresented groups.4,10,11,31 More research is urgently needed.

Organizations have long sought to promote respect and to protect individuals from mistreatment through evidence-based interventions including implicit bias training, leadership development, anonymous reporting systems, and bystander training, among others. However, to our knowledge, there have been no studies in the health care field that measure how these protective mechanisms impact the occupational well-being of the people they are designed to protect. Our findings suggest that organizations may be able to influence the well-being of physicians by creating systems to ensure that they are treated with respect and dignity. Having these systems in place was significantly associated with reduced burnout, increased professional fulfillment, and reduced intent to leave the organization.

We explored bystander intervention as a specific example of protective environmental factors and found that it was independently associated with improved occupational well-being. This modest positive association between bystander intervention and occupational well-being was present both for physicians who reported mistreatment and those who did not. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate an association between perceived bystander intervention and occupational well-being.

Reducing mistreatment and enhancing protective systems has inherent ethical value, particularly considering that mistreatment is experienced inequitably based on race and gender. Initiatives that prioritize reducing mistreatment of women and physicians of color can help reduce gender- and race-based workplace inequities, and thereby support greater racial and gender diversity among physicians. In addition to these intrinsic values, our study suggests that such essential efforts may also result in benefits to patients, physicians, and health care organizations through reduction of burnout and its associated impacts. Physician burnout has been associated with harms to patients, including increased medical errors,32,33 poor patient experience of care,34,35 and worse patient outcomes in some studies,36,37 as well as harms to physicians, including increased rates of depression and substance abuse.38,39 Physician burnout threatens patient access to care through its association with increased rates of physician turnover and reduction in professional effort,40,41 which also impose additional recruitment costs on health care organizations.14 With occupational burnout rates of 40% to 60% documented in large, national studies over the last decade, physician burnout remains a major threat to physicians, patients, and health care organizations.23 Thus, any intervention that reduces the incidence of physician burnout is likely to yield dividends for the health care system across multiple dimensions.

Strengths and Limitations

Our response rate of nearly 80% increases confidence that the sample is representative. There are also several limitations worth noting in this study. We used a binary gender classification owing to small sample size for other genders, which did not allow us to explore the experience of physicians who do not identify as male or female. The small number of non-White respondents precluded analysis of ethnicity, limiting the generalizability of our data on race. Caution is warranted in interpreting observed differences in descriptive data. No evaluation of statistical significance of observed difference between specific subgroup pairs was attempted due to the small number of underrepresented racial categories. Results indicate only that distribution of mistreatment was not equal across racial groups. The cross-sectional nature of our survey limited our ability to assess the directionality of the association between perceptions of protective systems and occupational well-being, and evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions was not possible. We did not assess the frequency or severity of mistreatment experiences. Further research is necessary to elucidate how frequency and severity of mistreatment impact outcomes. Given that the survey was promoted by the respondents’ employer (although administered by an independent surveyor), the potential exists for multiple types of response biases. Our study is also a single center experience which may affect the generalizability of some of our findings. Although it is unlikely the relationship between mistreatment and dimensions of occupational well-being are specific to this center, the prevalence of mistreatment may vary across centers and practice setting.

Conclusions

This survey study found that workplace mistreatment was common for physicians. Patients and visitors were the most common source of mistreatment. We found disparities in mistreatment by gender and race, a strong negative association between mistreatment and occupational well-being, and a positive association between occupational well-being and protective workplace systems. These findings highlight the urgent need for organizations to put systems in place to reduce the incidence of mistreatment, and for more research to determine which systems will be most effective.

eAppendix 1. Methods for Developing the Mistreatment, Protection, and Respect (MPR) Measure

eAppendix 2. MPR Measure Full Text

eTable 1. Experience of Mistreatment, by Response Versus Missing Gender or Race Data

eTable 2. Parameter Estimates from Regression Analyses of Associations of Mistreatment and Protective Factors with Standardized Scores for Burnout and Professional Fulfillment (PF)

References

- 1.Ayyala MS, Rios R, Wright SM. Perceived bullying among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2019;322(6):576-578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes KL, McGuire L, Dunivan G, Sussman AL, McKee R. Gender bias experiences of female surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):e1-e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chadaga AR, Villines D, Krikorian A. Bullying in the American graduate medical education system: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlitzkus LL, Vogt KN, Sullivan ME, Schenarts KD. Workplace bullying of general surgery residents by nurses. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e149-e154. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuce TK, Turner PL, Glass C, et al. National evaluation of racial/ethnic discrimination in US surgical residency programs. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(6):526-528. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng MY, Neves SL, Rainwater J, et al. Exploration of mistreatment and burnout among resident physicians: a cross-specialty observational study. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):315-321. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00905-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):487-495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bourmont SS, Burra A, Nouri SS, et al. Resident physician experiences with and responses to biased patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2021769-e2021769. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, et al. Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1678-1685. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artino AR Jr, Durning SJ, Sklar DP. Guidelines for reporting survey-based research submitted to Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):337-340. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys (9th ed.). Published 2016. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf

- 13.Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: Reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):11-24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady KJS, Ni P, Carlasare L, et al. Establishing crosswalks between common measures of burnout in US physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(4):777-784. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06661-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trockel MT, Menon NK, Rowe SG, et al. Assessment of physician sleep and wellness, burnout, and clinically significant medical errors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028111-e2028111. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balch Samora J, Van Heest A, Weber K, Ross W, Huff T, Carter C. Harassment, discrimination, and bullying in orthopaedics: a work environment and culture survey. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(24):e1097-e1104. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halim UA, Riding DM. Systematic review of the prevalence, impact and mitigating strategies for bullying, undermining behaviour and harassment in the surgical workplace. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1390-1397. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudol NT, Guaderrama NM, Honsberger P, Weiss J, Li Q, Whitcomb EL. Prevalence and nature of sexist and racial/ethnic microaggressions against surgeons and anesthesiologists. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(5):e210265-e210265. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miedema BB, Hamilton R, Tatemichi S, et al. Monthly incidence rates of abusive encounters for Canadian family physicians by patients and their families. Int J Family Med. 2010;2010:387202. doi: 10.1155/2010/387202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith-Coggins R, Prober CG, Wakefield K, Farias R. Zero tolerance: Implementation and evaluation of the Stanford medical student mistreatment prevention program. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):195-199. doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0523-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul-Emile K. How should organizations support trainees in the face of patient bias? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(6):E513-E520. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2019.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linzer M, Smith CD, Hingle S, et al. Evaluation of work satisfaction, stress, and burnout among US internal medicine physicians and trainees. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2018758-e2018758. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou AY, Panagioti M, Esmail A, Agius R, Van Tongeren M, Bower P. Factors associated with burnout and stress in trainee physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013761-e2013761. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson HM, Irish W, Strassle PD, et al. Associations between career satisfaction, personal life factors, and work-life integration practices among US surgeons by gender. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):742-750. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruzycki SM, Freeman G, Bharwani A, Brown A. Association of physician characteristics with perceptions and experiences of gender equity in an academic internal medicine department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915165-e1915165. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linzer M, Harwood E. Gendered expectations: do they contribute to high burnout among female physicians? J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):963-965. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad K, Poplau S, Brown R, et al. ; Healthy Work Place (HWP) Investigators . Time pressure during primary care office visits: a prospective evaluation of data from the healthy work place study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):465-472. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05343-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linzer M, Poplau S, Prasad K, et al. ; Healthy Work Place Investigators . Characteristics of health care organizations associated with clinician trust: results from the healthy work place study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196201. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglas M, Coman E, Eden AR, Abiola S, Grumbach K. Lower likelihood of burnout among family physicians from underrepresented racial-ethnic groups. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(4):342-350. doi: 10.1370/afm.2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071-1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anagnostopoulos F, Liolios E, Persefonis G, Slater J, Kafetsios K, Niakas D. Physician burnout and patient satisfaction with consultation in primary health care settings: evidence of relationships from a one-with-many design. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(4):401-410. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9278-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welle D, Trockel MT, Hamidi MS, et al. Association of occupational distress and sleep-related impairment in physicians with unsolicited patient complaints. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(4):719-726. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halbesleben JRB, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29-39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304493.87898.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tawfik DS, Scheid A, Profit J, et al. Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(8):555-567. doi: 10.7326/M19-1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30-38. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):168-174. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422-431. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner TB, Dilley SE, Smith HJ, et al. The impact of physician burnout on clinical and academic productivity of gynecologic oncologists: a decision analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):642-646. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Methods for Developing the Mistreatment, Protection, and Respect (MPR) Measure

eAppendix 2. MPR Measure Full Text

eTable 1. Experience of Mistreatment, by Response Versus Missing Gender or Race Data

eTable 2. Parameter Estimates from Regression Analyses of Associations of Mistreatment and Protective Factors with Standardized Scores for Burnout and Professional Fulfillment (PF)