Abstract

Background:

Annual vaccination is the most effective strategy for preventing influenza. We assessed trends and demographic and access-to-care characteristics associated with place of vaccination in recent years.

Methods:

Data from the 2014–2018 National Internet Flu Survey (NIFS) were analyzed to assess trends in place of early-season influenza vaccination during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to identify factors independently associated with vaccination settings in the 2018–19 season.

Results:

Among vaccinees, the proportion vaccinated in medical (range: 49%–53%) versus nonmedical settings (range: 47%–51%) during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons were similar. Among adults aged ≥18 years vaccinated early in the 2018–19 influenza season, a doctor’s office was the most common place (34.4%), followed by pharmacies or stores (32.3%), and workplaces (15.0%). Characteristics significantly associated with an increased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings among adults included household income ≥$50,000, having no doctor visits since July 1, 2018, or having a doctor visit but not receiving an influenza vaccination recommendation from the medical professional.

Conclusion:

Place of early-season influenza vaccination among adults who reported receiving influenza vaccination was stable over five recent seasons. Both medical and nonmedical settings were important places for influenza vaccination. Increasing access to vaccination services in medical and nonmedical settings should be considered as an important strategy for improving vaccination coverage.

Keywords: Influenza vaccination, trends, place of influenza vaccination, medical setting, nonmedical setting, National Internet Flu Survey (NIFS)

Introduction

Influenza is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among adults (1-4). Annual influenza epidemics typically occur during the late fall through early spring in the United States (1-4). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that influenza has resulted in 690,600 hospitalizations during the 2018-19 season; about 57% occurred among adults aged ≥65 years (2). Incidence of serious illness and death are higher among adults aged ≥65 years, children aged <2 years, pregnant women, and persons of any age who have medical conditions that place them at elevated risk for influenza complications (1).

Annual influenza vaccination is the primary tool for preventing and controlling influenza (1). Prior to 2010, the adult groups recommended for annual vaccination included persons aged ≥50 years, pregnant women, persons aged 18–49 years with medical conditions associated with higher risk of complications from influenza infection, healthcare personnel, and close contacts of high-risk persons (5). Since the 2010–11 influenza season, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended annual influenza vaccination for all persons aged ≥6 months (1). By the 2017–18 season, influenza vaccination coverage was about 40% for adults aged ≥18 years, well below the Healthy People 2020 target of 70% (6-8).

Previous studies have reported estimates of place of influenza vaccination receipt (9-12). However, trends and factors (demographic and access-to-care characteristics) associated with medical and nonmedical places of vaccination in recent years have not been assessed. Knowing where adults receive influenza vaccination can facilitate influenza vaccination campaign planning. This study used annual data from the 2014–2018 National Internet Flu Survey (NIFS) to assess trends in place of early-season influenza vaccination during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons and to identify demographic and access-to-care characteristics associated with place of vaccination in the 2018–19 season.

Methods

The NIFS was conducted for CDC by Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International and Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (GfK) Custom Research, LLC, usually from late October through early November each year. This annual survey collected information about self-reported early-season influenza vaccination, place of vaccination, provider recommendation/offer status, knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers related to influenza vaccination in the non-institutionalized U.S. adult population. The survey was conducted with a random sample of participants in the GfK KnowledgePanel®, a probability-based Internet panel designed to be representative of the English-speaking, non-institutionalized U.S. population aged ≥18 years (13). All NIFS estimates were weighted to reflect the non-institutionalized U.S. population aged ≥18 years. The 2018 NIFS was conducted November 1–November 15, 2018. For the 2014–2018 NIFS, the sample sizes (number of participants who completed survey) were 3,325, 3,301, 4,305, 4,367, and 4,286, respectively, and weighted completion rates were 53.1%, 57.6%, 61.1%, 59.8%, and 53.1%, respectively.

Respondents were asked whether they had received an influenza vaccination since July 1 of each year. For adults who received an influenza vaccination, respondents were asked “At what kind of place did you get a flu vaccination?” The following categories were listed for responses: (1) doctor’s office, (2) clinic or health center, (3) hospital, (4) health department, (5) workplace, (6) school, (7) pharmacy or drug store, (8) supermarket/grocery store, (9) senior center, (10) nursing home, (11) military-related place, (12) home, and (13) other (this is an open response: the responses were recoded into one of the categories listed from 1 to 12 if it fit, and for those did not fit to any categories remained as a separate “other” category). Individuals who declined to answer the place of vaccination question (n=1–7, and percentage=0.05–0.33% during 2014–2018) were excluded from the analysis. In the 2014–2018 NIFS surveys, a total of 1,384, 1,352, 1,923, 1,870, 2,132 participants, respectively, who reported receiving influenza vaccination with information on vaccination settings were included in the analysis.

Influenza vaccination, place of influenza vaccination, and covariates are all self-reported information. Responses to the question on place of influenza vaccination were divided into medical and nonmedical settings. Medical settings were doctor’s office, hospital/emergency department, clinic/health center/other medical place, and health department. Nonmedical settings were pharmacy/store, workplace, senior/community center, school, college, or other place(s). Covariates selected to examine associations of influenza vaccination with medical and nonmedical settings included: age group, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status, annual household income, region of residence, status of having had a doctor visit since July 1, 2018, and if so, receiving a provider recommendation for influenza vaccination, having a usual place for medical care, high-risk medical condition status, household size, health insurance status, and metropolitan statistical area (MSA) status.

Persons were considered to have a high-risk medical condition if they had ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had a lung condition (including chronic asthma), diabetes, heart disease (other than high blood pressure, heart murmur, or mitral valve prolapse), a kidney condition, a liver condition, obesity, sickle cell anemia or other anemia, a neurologic or neuromuscular condition that makes it difficult to cough, or a weakened immune system caused by chronic illness or by medicines taken for chronic illness such as cancer, chemotherapy, HIV/AIDS, steroids, and transplant medicines.

The unadjusted proportions of early-season vaccinated respondents that were vaccinated at each type of place were estimated for influenza seasons both overall and within subgroups defined by various socio-demographic variables. T-tests were used to compare estimates with the referent group. Tests for linear trend from the 2014–2015 season through the 2018–2019 season were performed using a weighted linear regression on the season-specific estimates using season number as the independent variable and weights as the inverse of the estimated variance of the estimated vaccination coverage. The estimated slope coefficients were interpreted as the average change across seasons assuming a linear increase. Additionally, t-tests were used for comparison with the prior adjacent influenza season. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to evaluate factors independently associated with early-season influenza vaccination in nonmedical versus medical settings during the 2018–19 influenza season and adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, version 11.03) (14) and survey analysis weights were used to calculate point estimates and 95% CI. All tests were 2-sided with alpha set at 0.05.

Results

Overall, early-season influenza vaccination coverage among adults during the 2014–15 (40.4%) through 2018–19 seasons (44.9%) did not significantly change (test for trend, p>0.05). Place of early-season influenza vaccination remained stable over the five influenza seasons assessed. Changes in all types of settings assessed during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons were not significant (test for trend, p>0.05) except in workplaces (test for trend, p<0.05), where a significant average annual decrease of 0.9 percentage points was observed (Table 1, Figure 1). During the 2014–15 through the 2018–19 seasons, the percentage of early-season vaccinated adults aged ≥18 years who received influenza vaccination in medical settings was 50.8%, 48.9%, 52.9%, 50.3%, and 48.8%, respectively, and in nonmedical settings was 49.2%, 51.1%, 47.1%, 49.7%, and 51.2%, respectively, with no differences from one season to the next for both settings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported place of early-season influenza vaccination among adults aged ≥18 years—National Internet Flu Survey, United States, 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons*

| Influenza season |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 2014–15 (N=1,384) |

2015–16 (N=1,352) |

2016–17 (N=1,923) |

2017–18 (N=1,870) |

2018–19 (N=2,132) |

Average annual change |

||||||

| Place | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| Percent vaccinated | 3.279 | 40.4 (38.6, 42.3) | 3.248 | 39.9 (38.0, 41.8) | 4,268 | 40.6 (38.9, 42.4) | 4,331 | 38.5 (36.9, 40.2) | 4,251 | 44.9 (43.2, 46.7) ‡ | 0.7 (−1.9, 3.2) |

| Medical settings † | 711 | 50.8 (47.9, 53.7) | 663 | 48.9 (45.8, 52.0) | 1,031 | 52.9 (50.2, 55.6) | 963 | 50.3 (47.6, 52.9) | 1,048 | 48.8 (46.3, 51.3) | −0.3 (−2.2, 1.5) |

| Doctor’s office | 473 | 33.2 (30.5, 36.0) | 441 | 33.0 (30.1, 36.0) | 730 | 37.5 (34.9, 40.1) ‡ | 661 | 34.7 (32.2, 37.3) | 742 | 34.4 (32.1, 36.9) | 0.3 (−1.6, 2.3) |

| Hospital/emergency department | 83 | 5.9 (4.7, 7.5) | 88 | 6.7 (5.2, 8.5) | 127 | 6.7 (5.5, 8.1) | 114 | 5.9 (4.8, 7.2) | 116 | 5.4 (4.4, 6.7) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) |

| Clinic/health center/other medical place | 139 | 10.1 (8.4, 12.1) | 120 | 8.3 (6.7, 10.1) | 158 | 7.8 (6.5, 9.3) | 170 | 8.6 (7.2, 10.2) | 172 | 7.9 (6.6, 9.4) | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.4) |

| Health department | 16 | 1.5 (0.9, 2.7)§ | 14 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.7)§ | 16 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8)§ | 18 | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8)§ | 18 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8)§ | −0.03 (−0.3, 0.2) |

| Nonmedical settings ∥ | 673 | 49.2 (46.3, 52.1) | 689 | 51.1 (48.0, 54.2) | 892 | 47.1 (44.4, 49.8) | 907 | 49.7 (47.1, 52.4) | 1,084 | 51.2 (48.7, 53.7) | 0.3 (−1.5, 2.2) |

| Pharmacy/store | 368 | 25.5 (23.1, 28.1) | 356 | 24.8 (22.3, 27.5) | 519 | 24.3 (22.2, 26.6) | 565 | 28.2 (25.9, 30.6) ‡ | 735 | 32.3 (30.1, 34.7) ‡ | 1.8 (−0.6, 4.1) |

| Workplace | 231 | 18.8 (16.6, 21.3) | 232 | 18.1 (15.9, 20.6) | 269 | 17.6 (15.6, 19.9) | 257 | 17.0 (15.0, 19.2) | 266 | 15.0 (13.2, 17.0) | −0.9¶ (−1.4, −0.4) |

| Senior/community center | 11 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.3)§ | 16 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.4)§ | 14 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1)§ | 18 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3)§ | 13 | 0.5 (0.3, 1.0)§ | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.1) |

| School/college | 15 | 1.2 (0.7, 2.1)§ | 20 | 2.0 (1.2, 3.3)§ | 15 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7)§ | 14 | 1.0 (0.5, 1.7)§ | 19 | 1.4 (0.9, 2.4)§ | −0.02 (−0.4, 0.4) |

| Other place | 48 | 3.0 (2.2, 4.0) | 65 | 5.0 (3.8, 6.6) ‡ | 75 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.7) | 53 | 2.8 (2.0, 3.8) | 51 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.7) | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.4) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval

Individuals reported receiving influenza vaccination during July through the interview date of each season. The interview was usually conducted between the end of October and early November.

Doctor's office, hospital/emergency department, clinic/health center, or health department.

P<0.05 for comparison with the prior adjacent influenza season. Statistically significant differences are bolded.

The estimates in this table are population distribution proportions except for top row. Suppression of proportions where the sample size is <30 is not indicated.

Pharmacy/store, workplace

P< 0.05 for overall trend. Tests for linear trend from the 2014–2015 season through the 2018–2019 season were performed using a weighted linear regression on the season-specific estimates using season number as the independent variable and weights as the inverse of the estimated variance of the estimated vaccination coverage. The estimated slope coefficients were interpreted as the average change across seasons assuming a linear increase. senior/community center, school, college or other place.

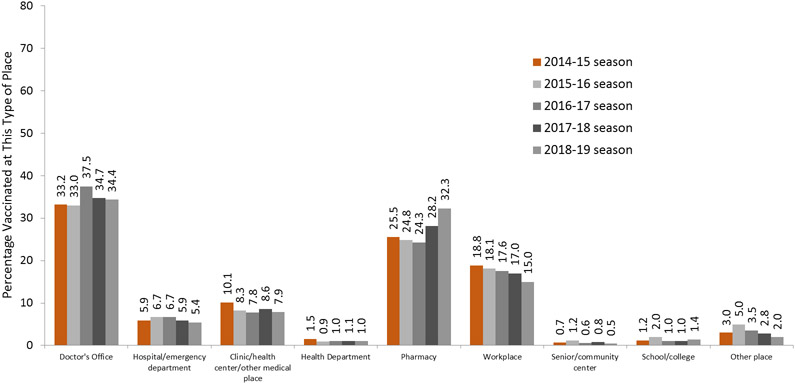

Figure 1.

Reported place of influenza vaccination, adults aged ≥18 years, United States, National Internet Flu Survey, 2014-15 through 2018-2019 Influenza Seasons

Among adults vaccinated during the 2018–19 influenza season, a doctor’s office was the most common place (34.4%) for receipt of early-season influenza vaccination (Table 1, Figure 1). Though the overall trend test for vaccination in a doctor’s office was non-significant, there was a significant increase in receipt of influenza vaccination at a doctor’s office from the 2015–16 season (33.0%) to the 2016–17 season (37.5%) (Table 1, Figure 1). The next most common place of vaccination was a pharmacy or store (32.3% in the 2018–19 season). Though the overall trend test for pharmacy or store was non-significant, there were significant increases in receipt of vaccination in this setting from the 2016–17 season (24.3%) to the 2017–18 season (28.2%), and the 2018–19 season (32.3%). The third most common place of vaccination was the workplace (15.0% in the 2018–19 season), with a significant decrease over the seasons assessed. The fourth most common place of vaccination was a clinic, health center, or other medical place (7.9%), with no differences observed from one season to the next (Table 1, Figure 1).

Overall, during the 2014–2015 through the 2018–19 seasons, the proportion of adults aged 18–64 years reporting vaccination in medical settings was similar to that of adults aged ≥65 years except in the 2017–18 season, where a significantly lower proportion of adults aged 18–64 years were vaccinated in medical settings (48.7%) compared with adults aged ≥65 years (54.1%) (Table 2). The proportion of adults aged 18–64 years reporting vaccination in nonmedical settings over seasons assessed was similar to that of adults aged ≥65 years except in the 2017–18 season, where a significantly higher proportion of adults aged 18–64 years were vaccinated in nonmedical settings (51.3%) compared with adults aged ≥65 years (45.9%) (Table 2). There was a significant decrease in the percentage of adults aged ≥65 years receiving vaccination in medical settings from the 2017–18 season (54.1%) to the 2018–19 season (49.0%) (Table 2). A significant increase was observed among adults aged ≥65 years in nonmedical settings from the 2017–18 season (45.9%) to the 2018–19 season (51.0%) (Table 2). During the 2014–2015 through the 2018–19 seasons, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were significantly more likely to receive vaccination in medical settings compared with non-Hispanic whites (Table 2). Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were significantly less likely to receive vaccination in nonmedical settings compared with non-Hispanic whites (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported place of early-season influenza vaccination among adults by settings, age, and racial/ethnic group—National Internet Flu Survey, United States, 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons*

| Influenza Season |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | |

| Place | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| Medical settings † | 50.8 (47.9, 53.7) | 48.9 (45.8, 52.0) | 52.9 (50.2, 55.6) | 50.3 (47.6, 52.9) | 48.8 (46.3, 51.3) |

| Age group (in years) | |||||

| 18–64‡ | 50.7 (47.1, 54.4) | 47.7 (43.9, 51.6) | 52.0 (48.6, 55.4) | 48.7 (45.2, 52.1) | 48.7 (45.4, 51.9) |

| ≥65 | 50.9 (46.2, 55.7) | 51.6 (46.5, 56.7) | 55.4 (51.8, 59.0) | 54.1 (50.5, 57.6) § | 49.0 (45.6, 52.5) ∥ |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white only‡ | 44.6 (41.1, 48.2) | 45.6 (42.0, 49.3) | 47.8 (44.4, 51.2) | 46.7 (43.3, 50.1) | 43.6 (40.5, 46.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black only | 67.4 (60.3, 73.8) § | 56.6 (47.3, 65.5) § | 66.1 (59.4, 72.2) § | 62.4 (55.5, 68.8) § | 62.7 (55.7, 69.1) § |

| Hispanic | 67.4 (58.9, 74.9) § | 60.6 (49.9, 70.3) § | 62.0 (55.0, 68.5) § | 55.7 (48.7, 62.5) § | 58.1 (51.3, 64.7) § |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiple races | 51.8 (41.7, 61.8) | 48.2 (38.1, 58.5) | 55.6 (47.1, 63.8) | 50.6 (42.6, 58.6) | 54.0 (45.6, 62.2) § |

| Nonmedical settings ¶ | 49.2 (46.3, 52.1) | 51.1 (48.0, 54.2) | 47.1 (44.4, 49.8) | 49.7 (47.1, 52.4) | 51.2 (48.7, 53.7) |

| Age group (in years) | |||||

| 18–64‡ | 49.3 (45.6, 52.9) | 52.3 (48.4, 56.1) | 48.0 (44.6, 51.4) | 51.3 (47.9, 54.8) | 51.3 (48.1, 54.6) |

| ≥65 | 49.1 (44.3, 53.8) | 48.4 (43.3, 53.5) | 44.6 (41.0, 48.2) | 45.9 (42.4, 49.5) § | 51.0 (47.5, 54.4) ∥ |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white only‡ | 55.4 (51.8, 58.9) | 54.4 (50.7, 58.0) | 52.2 (48.8, 55.6) | 53.3 (49.9, 56.7) | 56.4 (53.3, 59.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black only | 32.6 (26.2, 39.7) § | 43.4 (34.5, 52.7) § | 33.9 (27.8, 40.6) § | 37.6 (31.2, 44.5) § | 37.3 (30.9, 44.3) § |

| Hispanic | 32.6 (25.1, 41.1) § | 39.4 (29.7, 50.1) § | 38.0 (31.5, 45.0) § | 44.3 (37.5, 51.3) § | 41.9 (35.3, 48.7) § |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiple races | 48.2 (38.2, 58.3) | 51.8 (41.5, 61.9) | 44.4 (36.2, 52.9) | 49.4 (41.4, 57.4) | 46.0 (37.8, 54.4) § |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval.

Individuals reported receiving influenza vaccination during July through the interview date of each season. The interview was usually conducted between the end of October and early November.

Doctor's office, hospital/emergency department, clinic/health center or health department.

Reference group

P<0.05 for comparison with the reference groups. Statistically significant differences are bolded.

P<0.05 for comparison with the prior adjacent influenza season and statistically significant difference is bolded.

Pharmacy/store, workplace, senior/community center, school, college or other place.

During the 2018–19 season among adults aged ≥18 years, vaccinated individuals who were significantly less likely to receive vaccination in nonmedical settings included non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, or non-Hispanic other or multiple races, those who were never married, who were unemployed or not in the workforce, and those who lived in the Western region of the United States compared with the respective reference groups; those categories of characteristics were significantly more likely to receive vaccination in medical settings compared with the respective reference groups (Table 3). Vaccinated individuals with greater than high school education, with an annual household income ≥$50,000, who had not had a doctor visit since July 1, 2018 or who had a doctor visit but did not receive a recommendation for influenza vaccination from a medical professional, and who did not have high-risk conditions were significantly more likely to receive vaccination in nonmedical settings compared with the respective reference groups; those categories of characteristics were significantly less likely to receive vaccination in medical settings compared with the respective reference groups (Table 3). Demographic and access-to-care characteristics associated with vaccination settings among adults aged 18–64 years were similar compared with adults aged ≥18 years.

Table 3.

Percentage of adults aged ≥18 years reported receiving early-season influenza vaccination in medical versus nonmedical settings as of mid-November of the 2018–19 influenza season*, by age group and selected characteristics—National Internet Flu Survey, United States, 2018

| Overall | 18–64 years | ≥65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Medical† unadjusted % (95% CI) |

Nonmedical‡ unadjusted % (95% CI) |

Medical unadjusted % (95% CI) |

Nonmedical unadjusted % (95% CI) |

Medical unadjusted % (95% CI) |

Nonmedical unadjusted % (95% CI) |

| Total | 48.8 (46.3, 51.3) | 51.2 (48.7, 53.7) | 48.7 (45.4, 51.9) | 51.3 (48.1, 54.6) | 49.0 (45.6, 52.5) | 51.0 (47.5, 54.4) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male§ | 46.5 (42.8, 50.3) | 53.5 (49.7, 57.2) | 46.2 (41.4, 51.1) | 53.8 (48.9, 58.6) | 47.2 (42.3, 52.2) | 52.8 (47.8, 57.7) |

| Female | 50.8 (47.3, 54.2) | 49.2 (45.8, 52.7) | 50.8 (46.4, 55.2) | 49.2 (44.8, 53.6) | 50.6 (45.8, 55.5) | 49.4 (44.5, 54.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white only§ | 43.6 (40.5, 46.7) | 56.4 (53.3, 59.5) | 41.7 (37.4, 46.0) | 58.3 (54.0, 62.6) | 47.2 (43.5, 51.0) | 52.8 (49.0, 56.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black only | 62.7 (55.7, 69.1)∥ | 37.3 (30.9, 44.3)∥ | 63.7 (55.6, 71.0)∥ | 36.3 (29.0, 44.4)∥ | 58.8 (45.5, 70.9)¶ | 41.2 (29.1, 54.5)¶ |

| Hispanic | 58.1 (51.3, 64.7)∥ | 41.9 (35.3, 48.7)∥ | 58.5 (50.9, 65.8)∥ | 41.5 (34.2, 49.1)∥ | 56.0 (41.5, 69.5)¶ | 44.0 (30.5, 58.5)¶ |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiple races | 54.0 (45.6, 62.2)∥ | 46.0 (37.8, 54.4)∥ | 54.6 (45.3, 63.5)∥ | 45.4 (36.5, 54.7)∥ | 51.0 (32.5, 69.2)¶ | 49.0 (30.8, 67.5)¶ |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married/living with partner§ | 46.9 (43.9, 50.0) | 53.1 (50.0, 56.1) | 46.8 (42.8, 50.8) | 53.2 (49.2, 57.2) | 47.4 (43.0, 51.7) | 52.6 (48.3, 57.0) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 48.3 (43.1, 53.5) | 51.7 (46.5, 56.9) | 47.9 (40.0, 56.0) | 52.1 (44.0, 60.0) | 48.7 (42.4, 55.0) | 51.3 (45.0, 57.6) |

| Never married | 55.7 (48.6, 62.5)∥ | 44.3 (37.5, 51.4)∥ | 54.2 (46.6, 61.6) | 45.8 (38.4, 53.4) | 72.9 (58.2, 83.9)¶,∥ | 27.1 (16.1, 41.8)¶,∥ |

| Education level | ||||||

| High school or less§ | 55.5 (50.8, 60.0) | 44.5 (40.0, 49.2) | 58.2 (52.1, 64.2) | 41.8 (35.8, 47.9) | 49.6 (43.4, 55.9) | 50.4 (44.1, 56.6) |

| Some college or college graduate | 46.1 (42.6, 49.7)∥ | 53.9 (50.3, 57.4)∥ | 45.3 (41.0, 49.8)∥ | 54.7 (50.2, 59.0)∥ | 48.4 (43.5, 53.3) | 51.6 (46.7, 56.5) |

| Above college graduate | 42.3 (37.0, 47.8)∥ | 57.7 (52.2, 63.0)∥ | 39.1 (32.3, 46.5)∥ | 60.9 (53.5, 67.7)∥ | 49.3 (42.3, 56.3) | 50.7 (43.7, 57.7) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed§ | 45.4 (41.9, 48.9) | 54.6 (51.1, 58.1) | 45.4 (41.7, 49.2) | 54.6 (50.8, 58.3) | 44.9 (37.0, 53.0) | 55.1 (47.0, 63.0) |

| Not employed/not in work force | 53.6 (50.0, 57.1)∥ | 46.4 (42.9, 50.0)∥ | 58.1 (51.5, 64.5)∥ | 41.9 (35.5, 48.5)∥ | 50.0 (46.2, 53.9) | 50.0 (46.1, 53.8) |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| <$35,000§ | 61.4 (55.9, 66.6) | 38.6 (33.4, 44.1) | 64.2 (56.9, 70.9) | 35.8 (29.1, 43.1) | 55.0 (47.7, 62.2) | 45.0 (37.8, 52.3) |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 55.8 (47.8, 63.5) | 44.2 (36.5, 52.2) | 59.6 (48.4, 69.9)¶ | 40.4 (30.1, 51.6)¶ | 48.9 (39.4, 58.5) | 51.1 (41.5, 60.6) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 43.2 (37.1, 49.5)∥ | 56.8 (50.5, 62.9)∥ | 42.5 (34.2, 51.3)∥ | 57.5 (48.7, 65.8)∥ | 44.5 (36.8, 52.5) | 55.5 (47.5, 63.2) |

| ≥$75,000 | 43.8 (40.4, 47.2)∥ | 56.2 (52.8, 59.6)∥ | 42.4 (38.2, 46.7)∥ | 57.6 (53.3, 61.8)∥ | 47.8 (42.8, 53.0) | 52.2 (47.0, 57.2) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast§ | 44.4 (38.9, 50.2) | 55.6 (49.8, 61.1) | 42.5 (35.3, 49.9) | 57.5 (50.1, 64.7) | 49.1 (41.4, 56.8) | 50.9 (43.2, 58.6) |

| Midwest | 48.4 (43.1, 53.8) | 51.6 (46.2, 56.9) | 47.1 (40.1, 54.2) | 52.9 (45.8, 59.9) | 51.3 (44.5, 58.1) | 48.7 (41.9, 55.5) |

| South | 45.4 (41.1, 49.7) | 54.6 (50.3, 58.9) | 46.3 (41.0, 51.8) | 53.7 (48.2, 59.0) | 42.9 (36.8, 49.1) | 57.1 (50.9, 63.2) |

| West | 58.5 (53.4, 63.5)∥ | 41.5 (36.5, 46.6)∥ | 59.6 (52.9, 65.9)∥ | 40.4 (34.1, 47.1)∥ | 56.0 (48.9, 62.8) | 44.0 (37.2, 51.1) |

| Visit to healthcare professional/received recommendation for influenza vaccination | ||||||

| Doctor visit/received recommendation for influenza vaccination§ | 60.3 (56.8, 63.7) | 39.7 (36.3, 43.2) | 62.7 (57.8, 67.2) | 37.3 (32.8, 42.2) | 55.8 (51.2, 60.3) | 44.2 (39.7, 48.8) |

| Doctor visit/did not receive recommendation for influenza vaccination | 43.7 (38.3, 49.2)∥ | 56.3 (50.8, 61.7)∥ | 43.4 (36.5, 50.5)∥ | 56.6 (49.5, 63.5)∥ | 44.5 (37.1, 52.2)∥ | 55.5 (47.86, 62.9)∥ |

| Did not visit doctor or healthcare professional | 32.5 (28.0, 37.4)∥ | 67.5 (62.6, 72.0)∥ | 32.0 (26.7, 37.8)∥ | 68.0 (62.2, 73.3)∥ | 34.6 (27.5, 42.4)∥ | 65.4 (57.6, 72.5)∥ |

| Has a usual place to go when sick? | ||||||

| Yes/more than one§ | 49.2 (46.6, 51.8) | 50.8 (48.2, 53.4) | 48.8 (45.4, 52.2) | 51.2 (47.8, 54.6) | 50.0 (46.5, 53.6) | 50.0 (46.4, 53.5) |

| No | 40.4 (29.6, 52.3)¶ | 59.6 (47.7, 70.4)¶ | 43.9 (31.3, 57.4)¶ | 56.1 (42.6, 68.7)¶ | 24.6 (11.5, 44.9)¶,∥ | 75.4 (55.1, 88.5)¶,∥ |

| Have high-risk** conditions for influenza complications | ||||||

| Yes§ | 53.8 (49.9, 57.5) | 46.2 (42.5, 50.1) | 53.6 (48.3, 58.8) | 46.4 (41.2, 51.7) | 54.0 (48.9, 58.9) | 46.0 (41.1, 51.1) |

| No | 45.5 (42.2, 48.9)∥ | 54.5 (51.1, 57.8)∥ | 46.0 (41.9, 50.1)∥ | 54.0 (49.9, 58.1)∥ | 44.2 (39.5, 49.0)∥ | 55.8 (51.0, 60.5)∥ |

| Household size | ||||||

| ≤3§ | 47.7 (44.9, 50.5) | 52.3 (49.5, 55.1) | 47.3 (43.5, 51.1) | 52.7 (48.9, 56.5) | 48.4 (44.9, 51.9) | 51.6 (48.1, 55.1) |

| ≥4 | 52.3 (46.4, 58.1)¶ | 47.7 (41.9, 53.6) | 51.8 (45.6, 58.0) | 48.2 (42.0, 54.4) | 57.2 (39.7, 73.0)¶ | 42.8 (27.0, 60.3)¶ |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes§ | 48.9 (46.3, 51.5) | 51.1 (48.5, 53.7) | 48.7 (45.4, 52.1) | 51.3 (47.9, 54.6) | 49.3 (45.9, 52.8) | 50.7 (47.2, 54.1) |

| No | 45.3 (31.7, 59.6) | 54.7 (40.4, 68.3)¶ | 47.0 (32.8, 61.7)¶ | 53.0 (38.3, 67.2)¶ | 26.8 (5.4, 70.2)¶ | 73.2 (29.8, 94.6)¶ |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) | ||||||

| MSA§ | 49.3 (46.6, 52.0) | 50.7 (48.0, 53.4) | 49.5 (46.0, 52.9) | 50.5 (47.1, 54.0) | 49.0 (45.2, 52.7) | 51.0 (47.3, 54.8) |

| Non-MSA | 44.5 (37.3, 52.0) | 55.5 (48.0, 62.7) | 41.8 (31.9, 52.4)¶ | 58.2 (47.6, 68.1)¶ | 49.4 (40.3, 58.5) | 50.6 (41.5, 59.7) |

Abbreviations: CI= confidence interval.

Individuals reported receiving influenza vaccination during July through the date of survey November 2018.

Doctor's office, hospital/emergency department, clinic/health center or health department.

Pharmacy/store, workplace, senior/community center, school, college or other place.

Reference group used for pairwise significance test.

P<0.05 by t-test when compared to reference group.

Estimate may be unreliable either due to small sample size (n<30) and/or CI half-width >10.

Respondents were defined as being at high risk for complications from influenza if they reported currently having any of the following conditions: asthma, diabetes, a lung condition other than asthma, heart disease (other than high blood pressure, heart murmur, or mitral valve prolapse), a kidney condition, sickle cell anemia or other anemia, a neurologic or neuromuscular condition, obesity, a liver condition, a weakened immune system caused by chronic illness or by medicines taken for a chronic illness such as cancer, chemotherapy, HIV/AIDS, steroids, and transplant medicines, or being currently pregnant.

During the 2018–19 season, among adults aged ≥65 years, never-married individuals were significantly less likely to receive vaccination in nonmedical settings than married or cohabitating individuals and were significantly more likely to receive vaccination in medical settings than married or cohabitating individuals. Those who had not had a doctor visit since July 1, 2018 or who had a doctor visit but did not receive a recommendation for influenza vaccination from a medical professional, those who reported not having a usual place to go when sick, and those who did not have high-risk conditions were significantly more likely to receive vaccination in nonmedical settings compared with the respective reference groups, and those categories of characteristics were significantly less likely to receive vaccination in medical settings compared with the respective reference groups (Table 3).

Multivariable logistic regression was performed, with settings (nonmedical versus medical settings) of receipt of influenza vaccination as the outcome, based on data from the 2018–19 season (Table 4). Among all age groups (≥18, 18–64, and ≥65 years), not having a doctor visit since July 1, 2018 (APR; 1.40, 1.47, and 1.29, respectively) or having a doctor visit but not receiving a recommendation for influenza vaccination from a medical professional (APR; 1.64, 1.74, and 1.43, respectively) was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings compared with the indicated reference group. Among both adults aged ≥18 years and 18–64 years, having an annual household income $50,000–$74,999 (APR; 1.37 and 1.45, respectively) and ≥ $50,000 (APR; 1.29 and 1.39, respectively) were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings. Being non-Hispanic black (APR; 0.79 and 0.80, respectively) or living in the Western region of the United States (APR; 0.75 and 0.73, respectively) were significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings. Among adults aged ≥65 years, not having a place to go for health care (APR=1.39) )and not having high-risk conditions (APR=1.17) were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings and never having been married (APR=0.54) was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of persons aged ≥18 years who reported receiving influenza vaccination in a nonmedical setting* versus medical setting† as of mid-November of the 2018–19 influenza season‡, by demographic and access-to-care characteristics — National Internet Flu Survey, United States, 2018

| Overall | 18–64 years | ≥65 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.97 (0.86, 1.10) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white only | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black only | 0.79 (0.66, 0.95) | 0.80 (0.64, 1.00) | 0.88 (0.65, 1.19) |

| Hispanic | 0.83 (0.71, 0.98) | 0.84 (0.70, 1.02) | 0.86 (0.62, 1.20) |

| Non-Hispanic other or multiple races | 0.88 (0.73, 1.05) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.07) | 0.90 (0.64, 1.26) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living with partner | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.30) | 1.00 (0.86, 1.18) |

| Never married | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.17) | 0.54 (0.34, 0.88) |

| Education level | |||

| High school or less | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Some college or college graduate | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.26) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.18) |

| Above college graduate | 1.00 (0.86, 1.17) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.32) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.13) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Not employed/not in work force | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.10) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) |

| Annual household income | |||

| <$35,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 1.10 (0.89, 1.36) | 1.08 (0.79, 1.47) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.40) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1.37 (1.14, 1.64) | 1.45 (1.12, 1.87) | 1.19 (0.95, 1.48) |

| ≥$75,000 | 1.29 (1.09, 1.54) | 1.39 (1.09, 1.76) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.36) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Midwest | 0.94 (0.81, 1.08) | 0.95 (0.79, 1.14) | 0.90 (0.73, 1.10) |

| South | 1.04 (0.92, 1.17) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | 1.06 (0.89, 1.27) |

| West | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88) | 0.73 (0.59, 0.90) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.03) |

| Visit to healthcare professional/received recommendation for influenza vaccination | |||

| Doctor visit/received recommendation for influenza vaccination | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Doctor visit/did not receive recommendation for influenza vaccination | 1.40 (1.23, 1.60) | 1.47 (1.23, 1.75) | 1.29 (1.09, 1.52) |

| Did not visit doctor or healthcare professional | 1.64 (1.46, 1.84) | 1.74 (1.49, 2.03) | 1.43 (1.22, 1.68) |

| Has a usual place to go when sick? | |||

| Yes/more than one | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 1.10 (0.89, 1.36) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.33) | 1.39 (1.05, 1.83) |

| Have high-risk§ conditions for influenza complications | |||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.88, 1.15) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34) |

| Household size | |||

| ≤3 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥4 | 0.90 (0.79, 1.03) | 0.92 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.14) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 1.08 (0.83, 1.39) | 1.06 (0.81, 1.38) | 1.54 (0.92, 2.56) |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) | |||

| MSA | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non-MSA | 1.09 (0.95, 1.25) | 1.12 (0.94, 1.34) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.26) |

Note: Boldface indicates significance (p<0.05 by t-test for comparisons within each variable with the indicated reference level).

Abbreviations: CI= confidence interval.

Pharmacy/store, workplace, senior/community center, school, college or other place.

Doctor's office, hospital/emergency department, clinic/health center or health department.

Individuals reported receiving influenza vaccination during July through mid- November 2018.

Respondents were defined as being at high risk for complications from influenza if they reported currently having any of the following conditions: asthma, diabetes, a lung condition other than asthma, heart disease (other than high blood pressure, heart murmur, or mitral valve prolapse), a kidney condition, sickle cell anemia or other anemia, a neurologic or neuromuscular condition, obesity, a liver condition, a weakened immune system caused by chronic illness or by medicines taken for a chronic illness such as cancer, chemotherapy, HIV/AIDS, steroids, and transplant medicines, or being currently pregnant.

Discussion

This study assessed national estimates of place of early-season influenza vaccination among adults over five recent influenza seasons. Changes in all types of settings of early-season influenza vaccination assessed during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons were not significant except for vaccination in workplaces, where a small but significant decrease was observed. During the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons, more than one out of every three vaccinated adults received influenza vaccination at a doctor’s office, followed by a pharmacy or store, where nearly one out of three vaccinated adults received influenza vaccination. The third most frequent vaccination setting was the workplace, where 15%–19% of vaccinated adults received influenza vaccination. All other settings for vaccination had a frequency of <10%.

One important finding from this study is that during the 2014–15 through 2018–19 seasons, adults aged ≥18 years received early-season influenza vaccination in medical settings (range: 49%–53%) and nonmedical settings (range: 47%–51%) at a similar rate. This finding demonstrates that medical and nonmedical settings were equally important for adults as settings for influenza vaccination. Over the seasons assessed, adults receiving vaccination in medical versus nonmedical settings significantly differed by race/ethnicity, education level, household income, high-risk condition status, and doctor visit status or whether receiving recommendation for influenza vaccination. Those differences in characteristics may affect percentages of place of vaccination in different settings. This information will be useful for planning and implementing strategies for improving influenza vaccination coverage (8-12, 15).

New partnerships between public health agencies and medical and nonmedical vaccination providers formed during the 2009 influenza A pdm09 (H1N1) pandemic resulted in an increase in the number of vaccination providers and locations where influenza vaccinations are delivered (9, 16). Nonmedical settings have become popular places for adult influenza vaccination due to convenience and lower costs (9, 10, 16). Studies have shown that influenza vaccination in nonmedical settings is safe and the incidence of adverse events is low (approximately 0.02%) (17-20). Public education efforts can emphasize the safety of vaccination in nonmedical settings and encourage those who may not visit their usual health care provider during the influenza season to seek vaccination in a convenient nonmedical setting (18-20). The popularity of receiving influenza vaccination in nonmedical settings suggests that extending efforts to improve influenza vaccination in nonmedical settings may increase vaccination coverage among adults (21). Strategies that allow nonmedical vaccination providers to participate in state immunization information systems, allow medical providers to verify patients who are vaccinated in other settings, and allow public health officials to track influenza vaccination receipt could help promote vaccination in nonmedical settings (21).

The proportion of adults reporting receiving an influenza vaccination at a pharmacy/store increased to 32% in the 2018–19 season compared with 28% and 24% in the 2017–18 and the 2016–17 influenza seasons, respectively. Previous studies indicated that the proportion of adults receiving influenza vaccination at a pharmacy/store has increased over time, with estimates of 5% in the 1998–99 influenza season, 6% in 2001–02, 6% in 2004–05, 18% in 2010–11, 20% in 2011–12, and 22% in the 2014–15 influenza season (9-11, 15). More states allowing pharmacists to administer influenza vaccinations to adults, more programs training pharmacists to vaccinate, and more pharmacies offering on-site influenza vaccinations might have contributed to this increase (9, 22). In 1999, only 22 states allowed pharmacists to administer influenza vaccinations to adults; by June 2009, all 50 states allowed pharmacists to administer influenza vaccinations to adults (9, 22). Allowing pharmacies to provide vaccinations has been associated with higher influenza vaccination coverage (23). One cross-sectional study showed that states that allowed pharmacists to provide vaccinations had significantly more adults aged 18–64 and ≥65 years (25.5%, and 68.4%, respectively) vaccinated than states without this legislation (21.6%, and 64.7%, respectively) (23). As a nontraditional setting, a pharmacy/store not only provides extended access, convenience, and a low-cost option for adults to receive annual influenza vaccination, but also could be an effective source for influenza vaccination during an influenza pandemic (16, 24, 25).

Workplaces were the third most common place that adults reported receiving early-season influenza vaccination. However, reported receipt of vaccination in workplaces significantly declined from 19% in the 2014–2015 season to 15% in the 2018–19 seasons, with an average decrease of 0.9 percentage points annually (p<0.05). Vaccination programs in the workplace could provide more convenient access to all routine adult vaccinations for working adults and enhance overall capacity of the health care system to effectively deliver vaccinations. This is particularly important for those who do not regularly access the health care system (15, 26).

Overall, for all seasons assessed, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were consistently less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive influenza vaccination in nonmedical settings. Using 2018–19 data, this association persisted after controlling for demographic and access-to-care characteristics. The findings from this study were consistent with those from previous studies (9, 10, 15). These associations may result from place of vaccination preferences, differences in vaccine-seeking behavior, differences in availability of nonmedical settings offering vaccinations, or disparate availability of workplace vaccination among socioeconomic groups (9).

Findings from our multivariable logistic model showed that across age groups, not having a doctor visit since July 1, 2018 or having a doctor visit where no recommendation for influenza vaccination by medical professional was received was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of receipt of vaccination in nonmedical settings. This finding suggests that the availability of influenza vaccination in nonmedical settings can complement health care provider efforts by reaching populations less likely to be seen by providers or less likely to receive recommendations for influenza vaccination from providers. Results from this study indicated that Western states have fewer non-medical vaccinations. Variation among region or states could be due to differing medical care delivery infrastructure, population composition, social economic factors, immunization laws, immunization programs, and other factors (27, 28).

Estimates from this study of places where adults received early-season influenza vaccination could also be compared with estimates among adults interviewed later in the influenza season based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). In the 2014–15 season, estimates of place of early- and later-season influenza vaccination (among individuals aged ≥18 years interviewed from November 1 through November 15, 2014, and January through June, 2015, respectively) (11) were 33.2% vs 39.4% at a doctor's office, 5.9% vs 7.2% at a hospital or emergency department, 10.1% vs 9.1% at a clinic or health center, 25.5% vs 22.2% at a pharmacy or store, and 18.8% vs 15.5% at workplaces (11). In the 2014–15 season, early- and later-season influenza vaccination coverage (among individuals aged ≥18 years interviewed from November 1 through November 15, 2014, and January through June, 2015, respectively) was 40.4% vs 43.6% (29).These findings indicate a higher proportion of adults received early-season influenza vaccination at a pharmacy, store, or workplace compared with later-season estimates.

The findings in this study are subject to several limitations. First, influenza vaccination status and place of vaccination were based on self-reported data and were not verified by medical records, so might be subject to recall or social-desirability bias (30). However, self-reported influenza vaccination status among adults has been shown to be adequately sensitive and specific (31) although there are no studies validating accuracy of place of vaccination. Second, health care personnel vaccinated in medical settings might have reported they were vaccinated at the workplace; therefore, the percentage of vaccinations in nonmedical settings might be overestimated. Third, high-risk medical conditions were also self-reported and not validated by medical records. Fourth, the findings reported here are early-season estimates of place of influenza vaccination. End-of-season estimates, and factors associated with them could differ. Fifth, comparisons of place of vaccination over seasons or sociodemographic groups do not address differences in access, choice, or total percent vaccinated. Sixth, survey completion response rates ranged from 53.1% to 61.1%, and place of vaccination may differ between survey respondents and non-respondents; survey weighting adjustments may not adequately control for these differences. Seventh, the analysis did not include the time when survey is completed, and earlier participants have less time to get vaccinated compared to those who completed survey at a latter period of time even though the survey was usually completed within two weeks. Finally, NIFS is an Internet panel survey; although the Internet panel was probability-based, the estimates may not represent all adults in the United States and bias might remain after weighting adjustments (32).

This study demonstrates the importance of both medical and nonmedical settings for annual influenza vaccination. Place of vaccination has changed very little over recent five influenza seasons. Monitoring place of vaccination can help shape future influenza vaccination programs targeted at specific groups. Medical and nonmedical vaccination providers can collaborate to improve influenza vaccination coverage during both routine influenza seasons and during influenza pandemics (1, 33, 34).

Acknowledgments:

Authors thank Mary Ann Hall, James A. Singleton, and Kimberly Nguyen for their important review of this manuscript.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

All authors have no conflicts of interest to be stated.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2010; 59(RR08);1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Averted by Vaccination in the United States. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2018-2019.html. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- 3.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalization in the United States. JAMA 2004;292:1333–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridges CB, Katz JM, Levandowski RL, Cox NJ. Inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccines (2007), fifth edition, pp 259–290. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2009; 58(RR08):1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccination coverage among adults in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/NHIS-2016.html. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of influenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2017–18 flu season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1718estimates.htm. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. Immunization and infectious diseases. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Place of influenza vaccination among adults-United States, 2010-2011 influenza season. MMWR 2011; 60(23):781–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu PJ, O'Halloran A, Ding H, Williams WW, Bridges CB, Kennedy ED. National and state-specific estimates of place of influenza vaccination among adult populations - United States, 2011-12 influenza season. Vaccine 2014;32(26):3198–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National and state-level place of flu vaccination among vaccinated adults in the United States, 2014–15 Flu Season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/place-vaccination-2014-15.htm Accessed July 11, 2019.

- 12.Santibanez TA, Vogt TM, Zhai Y, McIntyre AF. Place of influenza vaccination among children--United States, 2010–11 through 2013–14 influenza seasons. Vaccine 2016;34(10):1296–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowledge Panel. Available at: https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/US/documents/KnowledgePanel_-_A_Methodological_Overview.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 14.Explore SUDAAN 11. Available at: http://sudaansupport.rti.org/sudaan/index.cfm. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 15.Singleton JA, Poel AJ, Lu P, Nichols KL, Iwane MK. Where adults reported receiving influenza vaccination in the United States. Am J Infect Control 2005;33:563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroud C, Altevogt BM, Butler JC, Duchin JS. The Institute of medicine's forum on medical and public health preparedness for catastrophic events: regional workshop series on the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination campaign. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2011;5:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heilly SJ, Blade MA, Nichol KL. Safety of influenza vaccinations administered in nontraditional settings. Vaccine 2006;24(18):4024–4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergus GR, Ernst ME, Sorofman BA. Physician perceptions about administration of immunizations outside of physician offices. Prev Med 2001;32(3):255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst ME, Bergus GR, Sorofman BA. Patients' acceptance of traditional and nontraditional immunization providers. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41(1):53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coady MH, Galea S, Blaney S, et al. Project VIVA: a multilevel community-based intervention to increase influenza vaccination rates among hard-to-reach populations in New York City. Am J Public Health 2008;98(7):1314–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Vaccine Program Office National adult immunization plan, 2016. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/national-adult-immunization-plan/naip.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2020.

- 22.Immunization Action Coalition. States authorizing pharmacists to vaccinate. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/pdfs/pharm.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 23.Steyer TE, Ragucci KR, Pearson WS, Mainous AG. The role of pharmacists in the delivery of influenza vaccinations. Vaccine 2004;22(8):1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta R. Enhancing community partnerships during a public health emergency: the school-located vaccination clinics model in Kanawha County, WV during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. W V Med J 2011;107:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, Cannon AE. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult immunization programs in nontraditional settings: quality standards and guidance for program evaluation. A report of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. MMWR 2000;49 (No. RR-1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaiman T, Ibrahim JK. State health department structure and pandemic planning. J Public Health Manag Pract 2010;16(2):E1–E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for certain health behaviors among selected local areas – United States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011. MMWR 2014;63 (SS09):1–149. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of influenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2017–18 flu season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1415estimates.htm. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 30.Lavrakas PJ (2008). Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. California: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolnick SJ, Parker ED, Nordin JD, et al. Self-report compared to electronic medical record across eight adult vaccines: do results vary by demographic factors? Vaccine 2013;31(37):3928–3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valliant R, Dever JA, & Kreuter F (2013). Practical tools for designing and weighting sample surveys. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: standards for adult immunization practice. Public Health Rep 2014;129(2):115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2020.