Abstract

Psychosis is the most ineffable experience of mental disorder. We provide here the first co‐written bottom‐up review of the lived experience of psychosis, whereby experts by experience primarily selected the subjective themes, that were subsequently enriched by phenomenologically‐informed perspectives. First‐person accounts within and outside the medical field were screened and discussed in collaborative workshops involving numerous individuals with lived experience of psychosis as well as family members and carers, representing a global network of organizations. The material was complemented by semantic analyses and shared across all collaborators in a cloud‐based system. The early phases of psychosis (i.e., premorbid and prodromal stages) were found to be characterized by core existential themes including loss of common sense, perplexity and lack of immersion in the world with compromised vital contact with reality, heightened salience and a feeling that something important is about to happen, perturbation of the sense of self, and need to hide the tumultuous inner experiences. The first episode stage was found to be denoted by some transitory relief associated with the onset of delusions, intense self‐referentiality and permeated self‐world boundaries, tumultuous internal noise, and dissolution of the sense of self with social withdrawal. Core lived experiences of the later stages (i.e., relapsing and chronic) involved grieving personal losses, feeling split, and struggling to accept the constant inner chaos, the new self, the diagnosis and an uncertain future. The experience of receiving psychiatric treatments, such as inpatient and outpatient care, social interventions, psychological treatments and medications, included both positive and negative aspects, and was determined by the hope of achieving recovery, understood as an enduring journey of reconstructing the sense of personhood and re‐establishing the lost bonds with others towards meaningful goals. These findings can inform clinical practice, research and education. Psychosis is one of the most painful and upsetting existential experiences, so dizzyingly alien to our usual patterns of life and so unspeakably enigmatic and human.

Keywords: Psychosis, lived experience, experts by experience, bottom‐up approach, phenomenology, premorbid stage, prodromal stage, first‐episode stage, relapsing stage, chronic stage, recovery, psychiatric treatment

Psychotic disorders have a lifetime prevalence of 1% 1 , with a young onset age (peak age at onset: 20.5 years) 2 . They are associated with an enormous disease burden 3 , with about 73% of healthy life lost per year 4 .

Psychosis is characterized by symptoms such as hallucinations (perceptions in the absence of stimuli) and delusions (erroneous judgments held with extraordinary conviction and unparalleled subjective certainty, despite obvious proof or evidence to the contrary). The nature of these symptoms makes psychosis the most ineffable experience of mental disorder, extremely difficult for affected persons to comprehend and communicate: “There are things that happen to me that I have never found words for, some lost now, some which I still search desperately to explain, as if time is running out and what I see and feel will be lost to the depths of chaos forever” 5 .

K. Jaspers often refers to the paradigm of “incomprehensibility” with respect to the primary symptoms of psychosis that cannot be “empathically” understood in terms of meaningful psychological connections, motivation, or prior experiences 6 . However, psychotic disorders – especially schizophrenia – have, more than any other mental condition, inspired repeated attempts at comprehension.

In the two‐hundred‐year history of psychosis, numerous medical treatises and accurate psychopathological descriptions of the essential psychotic phenomena have been published. However, this top‐down (i.e., from theory to lived experience) approach is somewhat limited by a narrow academic focus and language that may not allow the subjectivity of the lived experience to emerge fully.

Some evidence syntheses have summarized various aspects of the lived experience of psychosis 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , but again they were written by academics. On the other hand, numerous reports describing the subjective experience of psychosis have been produced by affected individuals 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 (see Table 1). Although useful, these reports are often limited by fragmented, contingent and contextual narratives that do not fully advance the broader comprehensibility of the experience.

Table 1.

Selection of publications on the lived experience of psychosis considered for the present review

| Beers CW. A mind that found itself 14 |

| Boisen AT. Out of the depths 15 |

| North CS. Welcome, silence 16 |

| Sommer R et al. A bibliography of mental patients' autobiographies: an update and classification system 17 |

| Clifford JS et al. Autobiographies of mental health clients: psychologists' uses and recommendations 18 |

| Saks ER. The center cannot hold 19 |

| Colori S. Experiencing and overcoming schizoaffective disorder: a memoir 20 |

| Weijun Wang E. The collected schizophrenias 21 |

| Sechehaye M. Autobiography of a schizophrenic girl 22 |

| Benjamin J, Pflüger B. The stranger on the bridge 23 |

| Geekie J et al (eds). Experiencing psychosis: personal and professional perspectives 24 |

| Williams S. Recovering from psychosis: empirical evidence and lived experience 25 |

| Stanghellini G, Aragona M (eds). An experiential approach to psychopathology: what is it like to suffer from mental disorders? 26 |

To our best knowledge, there are no recent studies that have successfully adopted a bottom‐up approach (i.e., from lived experience to theory), whereby individuals with the lived experience of psychosis (i.e., experts by experience) primarily select the subjective themes and then discuss them with academics to advance broader knowledge. Among the various forms of collaboration available in the literature, co‐writing represents an innovative approach that may foster new advances 27 , 28 . It can be defined as the practice in which academics and individuals with the lived experience of a disorder are mutually engaged in writing jointly a narrative related to the condition. Co‐writing is based on the sharing of perspectives and meanings about the individual's suffering. Collaborative writing must honour the challenge of maintaining each subject's diction and narrative style without capturing or formatting them in pre‐established narrative models 29 .

The present paper aims to fill the above‐mentioned gap in the literature by providing a bottom‐up co‐written review of the lived experience of psychosis.

In a first step, we established a collaborative team of individuals with the lived experience of psychosis and academics. This core writing group screened all first‐person accounts published in Schizophrenia Bulletin between 1990 and 2021 30 , and retrieved further personal narratives within and outside the medical field through text reading (e.g., autobiographical books, see Table 1) and qualitative research (e.g., narratives from clinical records or service users' magazines or newsletters). The material was included if consisting of primary accounts of the lived experience of psychosis across its clinical stages (premorbid, prodromal, first episode, relapsing, and chronic). Primary accounts of the experience of recovery or of treatments received for psychosis were also included.

We performed automated semantic analyses on Schizophrenia Bulletin first‐person accounts, extracting the list of experiential themes relating to the disorder across its clinical stages and their interconnections, loading them into Gephi software, and building up network maps.

In a second step, the core writing group selected the lived experiences of interest, tentatively clustered them into broader experiential themes, and identified illustrative quotations. The material was stored on a cloud‐based system (i.e., google drive) fully accessible to all members of the group.

In a third step, the initial selection of experiential themes and quotations was collegially shared and discussed in two collaborative workshops, which involved numerous individuals with the lived experience of psychosis as well as family members and carers, to ensure that the most prominent themes were being considered and to collect users' and carers' interpretation of these themes.

The workshops involved representatives from the Global Mental Health Peer Network (https://www.gmhpn.org); the Global Alliance of Mental Illness Advocacy Networks (GAMIAN) ‐ Europe (https://www.gamian.eu); the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (https://www.slam.nhs.uk); the Young Person's Mental Health Advisory Group (https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/ypmhag ); the Outreach And Support in South‐London (OASIS) (https://www.meandmymind.nhs.uk) Service Users Group; the South London and Maudsley NHS Recovery College (https://www.slamrecoverycollege.co.uk); the Black and Minority Ethnic Health Forum Croydon (https://cbmeforum.org); the UK Mental Health Foundation (https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk); the Faces and Voices of Recovery (https://facesandvoicesofrecovery.org); and the Asociación Española de Apoyo en Psicosis (AMAFE) (https://www.amafe.org).

In a final step, the selection of experiential themes was revised and enriched by adopting a phenomenologically‐informed perspective 31 , 32 , 33 . The revised material was then shared again across all collaborators in google drive and finalized iteratively. All individuals with lived experience and researchers who actively contributed to this work were invited to be co‐authors of the paper. Representatives from service user and family groups were reimbursed for their time according to the guidelines by the UK National Institute for Health Research (https://www.invo.org.uk).

In this paper, the words spoken or written by individuals with the lived experience of psychosis are reported verbatim in italics, integrated by co‐authors' comments and phenomenological insights.

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF PSYCHOSIS ACROSS ITS CLINICAL STAGES

This section addresses the subjective experience of psychosis across the clinical stages of this condition: premorbid, prodromal, first episode, relapsing, and chronic 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 .

The premorbid stage starts in the perinatal period and is often asymptomatic; it is generally associated with preserved functioning 38 , although delays in milestones may emerge 39 . Accumulation of further risk factors during infancy and young adulthood 40 may lead to the emergence of a clinical high‐risk state for psychosis; this stage is often termed “prodromal” in the retrospective accounts of individuals with the lived experience. The prodromal stage is characterized by attenuated psychotic symptoms that can last years, do not reach the diagnostic threshold for a psychotic disorder, but are typically associated with some degree of functional and cognitive impairment 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 . These manifestations can then progress to a subsequent stage of fully symptomatic mental disorder (first episode of psychosis) and then persist, especially if treated sub‐optimally, leading to a relapsing stage and, for a proportion of cases, a subsequent chronic stage 38 .

Premorbid stage

An early, inner experience of loneliness and isolation

“When growing up I was quite a shy child… I was usually uncomfortable around kids of my own age” 46 . Figure 1 shows that the most frequent cluster of lived experiences in the premorbid stage of psychosis is represented by feelings of loneliness and isolation – variably referenced as being “introverted” 47 , “loner” 48 , 49 , 50 or “isolated” 51 – already reported during childhood: “I admitted I was a loner and was probably somewhat backwards socially. I had never had a boyfriend, rarely even dated, and my friendships with girls were limited and superficial” 48 .

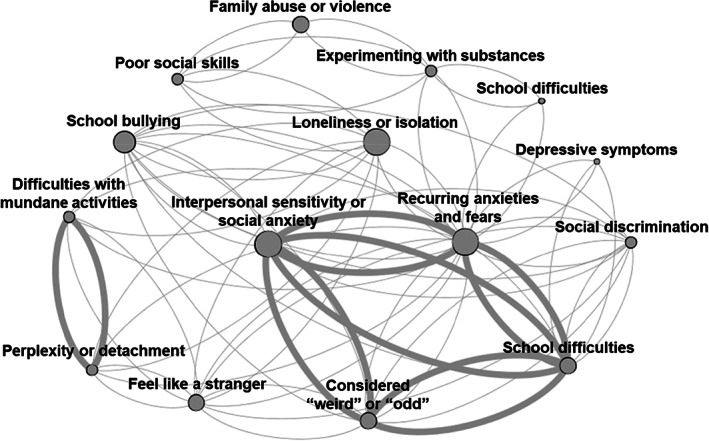

Figure 1.

Network map of lived experiences of psychosis during the premorbid stage. The nodes represent the experiential themes, and the edges represent the connections between them. The size of each node reflects the number of first‐person accounts addressing that experiential theme. The thickness of the edges reflects the number of connections between the themes.

This weak “attunement” in social interactions during childhood 52 has been captured by Bleuler's 53 concept of “latent schizophrenia” and Kretschmer's 54 definition of “schizothymic” and “schizoid” temperaments. Recent meta‐analyses have confirmed that loneliness is a core experiential domain during subclinical psychosis 55 . Loneliness has been frequently associated with experiences of social anxiety 46 , 56 and recurring fears 51 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , obsessive ruminations 59 , depressed mood 57 , and a heightened sensitivity to social interactions 14 , 60 , 61 : “I was too shy to raise my hand, and although my parents were very sociable and outgoing, I would hide behind my mum when meeting strangers” 23 .

These experiences color the emotional life of the individuals before the emergence of attenuated psychotic symptoms 51 , 58 . Loneliness is also frequently associated with early adverse experiences, such as social discrimination 60 , 62 , school bullying 50 , 60 , 63 , 64 , abuse or exposure to prolonged familial conflicts and violence 65 , 66 , which further amplify the sense of subjective alienation, fear and isolation (see Figure 1): “The abuse I had in my years of schooling… exacerbated anger and fear, which as I remember had always been there anyway” 60 .

Loss of common sense and natural self‐evidence

“When I was younger, I used to stare at the words on the pages of a book until they became so unfamiliar that they were practically incomprehensible to me even if I had learnt their meanings before. Then I would wonder, why do words mean anything anyway? They are just letters put together by some unspoken rule… What is this hidden rule? The hidden rules that govern thoughts and behaviors were not transparent to me although others seemed to know them” 67 . Another core experiential theme during the premorbid stage of psychosis is this diminished intuitive grasp of how to naturally conduct natural, everyday tasks like reading a book or interactions: “I was forever making remarks and behaving in a way that would slightly alienate people. This was because I would have to grasp situations by apprehending their parts rather than grasping them intuitively and holistically” 60 .

Common sense is defined by Blankenburg 68 as the tacit (implicit) understanding of the set of “rules of the game” that disciplines and guides human interactions. A “crisis in common sense” 68 is the main root of the premorbid subjective experience of psychosis since childhood, intensifying over the subsequent stages 69 : “Rules about how to deal with others were learnt and memorized instead of being intrinsically felt. What should come naturally, and without effort, became a difficult cognitive task” 67 .

Fragile common sense erodes interpersonal attunement (and vice versa) and may drive individuals towards an eccentric self‐positioning that is marginal to commonsensical reality, situating them at the edges of socially shared beliefs 70 and values 69 , 71 . Fragile common sense relates to the subjective feelings of being “odd” 60 , 72 or “weird” 56 (see Figure 1). Individuals may feel ephemeral, lacking a core identity, profoundly (often ineffably) different from others and alienated from the social world, a state that has been termed “diminished sense of basic‐self” 73 , 74 : “I remember it very precisely. I must have been 4 or 5 years old. I was starting dance class, and I was looking in the mirror. I was standing next to the other kids, and I remember that I looked alien. I felt like I sort of stuck out from that large wall mirror. As if I wasn't a real child. This feeling has been very persistent from very early on” 75 .

Empirical studies have confirmed that this odd “feeling like a stranger” 62 (see Figure 1) and isolated (e.g., schizoid or schizotypal) personality organization may present features qualitatively similar to psychosis 76 , and be associated with an increased risk of later developing the disorder 52 . Detachment from common sense is also related to a pervasive sense of “perplexity” (see Figure 1), frequently characterizing the premorbid stage of psychosis 51 , 67 : “A certain perplexity has always been a part of how I experience the world and its inhabitants” 67 .

Abnormal body experiences, such as the sense of being a disembodied self, may also be reported: “The first disturbing experience I remember was discomfort in my very own body. Because I didn't feel it. I didn't feel alive. It didn't feel mine. I was just a kid, but ever since, I never felt a feeling of fusion or harmony between ‘me’ and ‘my’ body: it always felt like a vehicle, something I had to drive like a car” (personal communication during the workshops).

Overall, the disconnectedness from common sense translates into real‐world feelings of inadequate social skills 48 , 56 , 60 , 66 , difficulties at school 57 , and problems in mundane daily activities 51 : “It made me inept about mundane things such as washing up, getting a haircut when I needed it, doing the bins, and little things like that – which really have to be done, just to get on with life” 51 . These impairments can be so profound as to disrupt the individual's identity 51 , 58 , 60 (Jaspers' awareness of the identity of the self, or ego‐identity 6 ).

Prodromal stage

A feeling that something important is about to happen

The subjective experience of the psychosis prodrome is marked by an intense feeling that something very important is “about to happen” 77 , that the individual is on the verge of finding out an important “truth” about the world 78 , 79 (see Figure 2). K. Conrad calls this initial expectation phase the Trema (stage fright) 77 . The Trema can last from a few days to months, or even years 6 , and is characterized by delusional mood (Wahnstimmung in the German tradition): an “uncanny” (“unheimlich” in the German tradition), oppressive inner sense of tension, as if something ominous and impending is about to happen (“something seems in the air” 6 ), but the individual is unable to identify what this might be precisely 77 : “Something is going on; do tell me what on earth is going on” 6 .

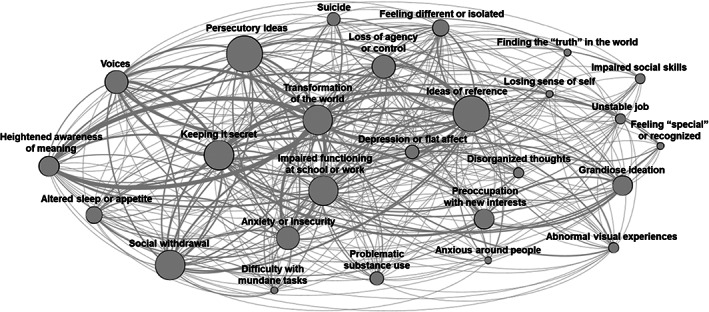

Figure 2.

Network map of lived experiences of psychosis during the prodromal stage. The nodes represent the experiential themes, and the edges represent the connections between them. The size of each node reflects the number of first‐person accounts addressing that experiential theme. The thickness of the edges reflects the number of connections between the themes.

During this experience, time is suspended. Individuals live in an elusive and pregnant “now”, in which what is most important is always about to happen. Premonitions about oneself (“I felt something good was going happen to me” 60 ) and about the external world (“Something is going on as if some drama unfolding” 60 ) are common.

Delusional mood, according to Jaspers, marks the irruption of a primary psychotic process (i.e., not due to other conditions) that interrupts the development of personality 81 . As the world transforms, the crisis of common sense of the Trema intensifies, and known places or people become strange 57 , 82 and lose their familiarity 83 , often acquiring a “brooding” 47 or threatening connotation 62 , 67 , 82 , 84 : “Suddenly the room became enormous, illuminated by a dreadful electric light that cast false shadows. Everything was exact, smooth, artificial, extremely tense; the chairs and tables seemed models placed here and there. Pupils and teachers were puppets revolving without cause, without objective. I recognized nothing, nobody. It was as though reality, attenuated, had slipped away from all these things and these people. Profound dread overwhelmed me… I heard people talking, but I did not grasp the meaning of the words” 22 .

Individuals feel as if they are the only ones noticing these changes: “I felt I was the only sane person in the world gone crazy” 62 . In contemporary terms, the uncanniness of the delusional mood has been described as “living in the Truman Show”, quoting a movie in which the protagonist, Truman, gradually starts to realize that he has been living his life in a reality television show, becoming increasingly suspicious of his surrounding world 85 , 86 : “All seemed ever more unreal to me, like a foreign country… Then it occurred to me that this was not my former environment anymore. Somebody could have set this up for me as a scenery. Or else someone could be projecting a television show for me… Then I felt the walls and checked if there was really a surface” 67 .

Heightened salience of meanings in the inner and outer world

During the prodromal phase of psychosis, individuals feel assaulted by events personally directed to them 67 , 79 , 82 , 88 , accompanied by a strong need to unravel their obscure meaning 67 , 79 : “A leaf fell and in its falling spoke: nothing was too small to act as a courier of meaning” 69 . Seemingly innocuous everyday events assume new salient meanings 78 , 83 , 89 . Previously irrelevant stimuli are brought to the front of the perceptual field and become highly salient 90 . This perceptual background, until then unnoticed, now takes on a character of its own 77 : “At first, this started with sudden new perspectives on problems I had been struggling with, later the world appeared in a new manner. Even the places and people most familiar to me did not look the same anymore” 83 .

The enhanced salience of the environment can become an overwhelming experience 79 , 89 : “It was shocking the amount of detail I found in this new world. In a day, there are so many things the mind relegates to background information” 79 . Therefore, individuals become increasingly preoccupied with new themes and interests – often involving religion 48 , 91 , the paranormal 59 , 91 , or sciences 49 , 92 – and ideas of reference emerge 46 , 47 , 51 , 62 , 72 , 82 , 84 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 (see Figure 2).

Perturbation of the sense of self

Another core experience is described as follows: “I thought I was dissolving into the world; my core self was perforated and unstable, accepting all the information permeating from the external world without filtering anything out” 67 . The normal lived experience of the world is intertwined with a stable sense of selfhood 96 (“core self” 67 ), which demarcates the individuals from the surrounding world. During delusional mood with heightened salience of meanings and paranoid interpretation, the boundaries of the self are “perforated” 67 , the self becomes “permeated” 67 by the external world 51 and “unstable” 67 (see Figure 2).

A pre‐reflective sense of “mineness” (“ipseity” and Jaspers' awareness of being or existing 6 ) is the necessary structure for all experience to be subjective, i.e. to be someone's experience, instead of existing in a free‐floating state appropriated post‐hoc by the subject via an act of reflection 74 , 97 , 98 . This sense of ownership and agency (sense of “I”) of actions and emotions, that healthy people typically take for granted 99 , is essentially based on self‐presence and immersion in the world. The person's experience of being a vital subject of experience 97 is disrupted in psychosis, leading to experiences of dissolution 67 and losing one's sense of identity 51 , 66 : “This vacuousness of self… one cannot find oneself or be oneself and so has no idea who one is” 51 .

A key component of ipseity disturbances is hyper‐reflexivity (exaggerated self‐consciousness and self‐alienation), in which inner mental processes such as thoughts become reified and spatialized, resulting in hallucinatory experiences 97 . During the prodromal phase, these abnormal perceptual experiences are reported as brief and remitting 100 , or intensifying over time 47 , 101 : “At first, hallucinations are often small or momentary and can be as small as the appearance of eyes or a whisper of a voice” 100 . Perceptual experiences include hearing indistinct chatter or distorted sounds 61 , 95 , 101 , voices 61 , 67 , 102 , or visions 78 , 82 , 88 .

The “mineness” of thinking and emotions is gradually compromised (diminished self‐affection 97 ): “Some thoughts didn't seem to be my own. They seemed foreign, as though someone was putting them there” 88 . Individuals complain about intrusive thoughts or impulses 103 , losing control over their emotional and cognitive processes 51 , 79 , 104 , 105 , or feeling under the influence of external forces 82 , although these experiences are typically transient.

Perplexity as lack of immersion in the world

An intense sense of perplexity is the hallmark of the emotional experience during the prodromal stage of psychosis 67 , 77 , 78 : “During that time reality became distant, and I began to wander around in a sort of haze, foreshadowing the delusional world that was to come later” 78 . Perplexity here refers to a lack of immersion in the world, an experience of puzzlement and alienation 106 which may acquire a threatening quality: “The sense of perplexity and feeling threatened by others preceded the fully formed voices by just over two years” 67 .

A pervasive sense of insecurity starts to creep in 82 , 84 , 89 , potentially leading to panic attacks 107 and experiences such as feeling empty, shut‐off, depressed 50 , 62 , 88 , 101 , 108 , angry or frustrated 57 , 105 . Substance use and social withdrawal are typical coping mechanisms (see Figure 2) 84 , 101 , 103 .

However, the prodromal phase of psychosis is not always tainted by anxiety 109 . Pleasurable emotional experiences can coexist 49 , 58 , 61 , 110 : “At that time I was working on an entirely new reality… with emotional gratification beyond any reasonable comprehension. In fact, I experienced it, but I also experienced terror and hell” 110 .

Compromised vital contact with reality

During the prodromal phase of psychosis, individuals tend to lose vital contact with the world, experiencing increasing difficulties in interacting and communicating with others 92 , 111 : “People were incomprehensible, as well as the world. I did not understand my peers why they could have so much ‘fun’ just by engaging in gossip or in a party. I much preferred my own company” 67 .

Individuals describe withdrawing from family and friends 62 , 95 from the early years gradually, over a long time 60 , 64 , 112 , and experiencing emotional distress, a sense of isolation 46 , 66 , and impairment of social skills 66 , 82 (see Figure 2). They feel out of place or unable to communicate with others 113 or grasp commonsensical implicit social codes 60 , 67 , or feel excluded 46 , 114 as if they were different or inferior 51 , 57 (see Figure 2): “I felt different and alone. Seeing so many people in the school halls made me wonder how my life could be significant. I wanted to blend in the classroom as though I were a desk. I never spoke” 57 .

These experiences have been variously linked to the concept of “autism” 115 in psychosis, which has been understood as a “withdrawal to inner life” (Bleuler 53 ), or as the “loss of vital contact with reality” (Minkowski 116 ) and, more recently, quantified by deficits in the related construct of social cognition 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 .

Keeping it secret

During the prodromal phase of psychosis, individuals typically keep their anomalous subjective experiences secret: “These things caused me considerable anguish, but I continued to act as normal as I could for fear that any bizarre behavior would cause me to lose my job” 62 .

Individuals often hide their experiences from family and friends over a very long time 82 , 111 because they feel ashamed 58 , 79 of negative consequences 82 , and fear being labeled as “crazy” or “insane” 51 , 78 , 108 or being laughed at 64 , hoping for their problems to “clear up” 121 : “At 18, I couldn't study or focus but still kept everything to myself. My behavior looked ‘normal’ to others, as I was always a quiet child, an introvert” (personal communication during the workshops). Help‐seeking during the prodromal phase may be hindered by this difficulty of sharing the unusual experiences with others 122 . For children and young adolescents, it is generally harder to conceal their emerging symptoms 123 .

On the other hand, because of the insidious onset of the abnormal experiences, individuals may not realize that something “might be wrong” 67 , 82 . They may believe that it is common for other people to have these experiences 64 , 67 , or consider them “plausible” 49 .

Notably, not all individuals describe a prodromal phase, but some report an abrupt onset of the first episode 89 , 92 , 124 , 125 : “I experienced a great and normal life I was thoroughly enjoying, then I went straight into the first episode phase” (personal communication during the workshops).

First episode stage

A sense of relief and resolution associated with the onset of delusions

The first psychotic episode is characterized by an intensification of abnormal experiences, as visually shown by the increased density of Figure 3 compared to Figures 1 and 2.

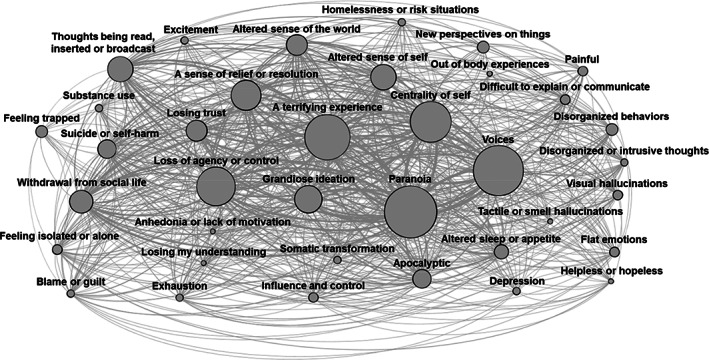

Figure 3.

Network map of lived experiences of psychosis during the first episode stage. The nodes represent the experiential themes, and the edges represent the connections between them. The size of each node reflects the number of first‐person accounts addressing that experiential theme. The thickness of the edges reflects the number of connections between the themes.

A sense of resolution emerges as a core experiential theme (see Figure 3): “It really feels as if I am suddenly capable of putting things in perspective, that the light has suddenly switched on inside of my head and that because of this I am capable of reasoning again” 63 . The pervasive sense of uncanniness and perplexity of the Trema is replaced by Conrad's Apophany (revelation) 77 , an unexpected experience of clarity or insight 60 , 83 , 126 , 127 . The individual suddenly “puts the pieces together” 89 , 126 , 127 , becoming aware of the “truth” in the world 79 or the “essence” of things 83 , discovering a delusional motif behind the abnormal perceptions and distressing experiences 79 , 83 (“aha experience” 77 ): “All of a sudden there came this ‘intuition’: that they had chosen me for the experiment. I was chosen to incarnate myself in one body and come to earth. That explained why I felt a stranger in my body. And a stranger on the earth too” 128 .

Individuals report being unable to shift away from or transcend 77 these new delusional perspectives 83 , 113 , 129 , 130 , 131 : “I told myself that I suddenly saw the real truth of the world as it was and as I had never seen it before” 79 .

The onset of delusions can provide the individual with a newfound role in the world that is more thrilling and meaningful than the uncanny reality of the Trema 60 , 67 , 83 , 89 , 132 , 133 , alongside a sense of excitement 60 , 61 , 126 or relief 67 , 83 , 89 (see Figure 3): “A relationship with the world was reconstructed by me that was spectacularly meaningful and portentous even if it was horrific” 60 ; “My destination after this is a place where everything is vibration, a pure state of consciousness, so elevated that everything is peace” 128 .

However, the sense of relief associated with Apophany is frequently contrasted with a difficult personal situation: “There was going to be a nuclear holocaust that would break up the continental plates, and the oceans would evaporate from the lava… My future wife and I were going to become aliens and have eternal life. My actual situation [however] was a sharp contrast. I was living in a downtown rooming house with only cockroaches for friends” 112 .

Delusions can be understood as new beliefs providing a satisfactory explanation of a strangely altered and uncanny reality and a basis for doing something about it – rather than incomprehensible and meaningless phenomena. Delusional beliefs can alleviate distress by replacing confusion with clarity, or promoting a shift from purposelessness to a sense of identity and personal responsibility 134 , 135 . Delusions can indeed enhance a person's experience of meaning and purpose in life 136 , contribute positively to establishing a “sense of coherence” 137 and partially provide a sense of purpose, belonging and self‐identity 138 .

Feeling that everything relates to oneself

The experience of delusion is often subjectively reported as: “Everything I ‘can’ grasp refers to ‘me’, even the tone of every voice I hear, or the people I see talking in the distance” 139 . In Conrad's model, Anastrophe (“turning back” of meanings) is the third phase following the “aha experience” 77 . All events and perceptions are experienced as revolving around the self (the “middle point”) 140 : “I have the sense that everything turns around me”, “I am like a little god, time is controlled by me”, “I feel as if I were the ego‐center of society”, “I became in a way for God the only human being, or simply the human being around whom everything turns” 141 .

The increased centrality of the self during a first psychotic episode (see Figure 3) is substantiated by the delusional self‐reference of messages on the radio or television 57 , 60 , 88 , the gestures or conversations of people in the street 57 , 100 , 139 , or even the color of people's clothes 130 : “Colors of jeans got more realistic” 142 . This is typically accompanied by a transformation of the experience of the lived space (i.e., the meaningful, practical space of everyday life). Individuals feel they are uncomfortably center‐stage. Other people look at them, spy on them, send them messages, or hide something from them. While in the center of the stage, individuals feel things directed to them bearing personal meanings: “Cat jumping cardboard box signified a spiritual change in me” or “TV, radio, people on buses refer to me” 142 . Individuals eventually become “overwhelmed” 79 , 89 , “flooded” or “swarmed” 139 by these external or internal stimuli, and the subjective experiences become exhausting 60 , 79 , 89 , 139 , 143 .

The self‐referential experiences are frequently associated with grandiose delusions 49 , 57 , 60 , 79 , 89 , 91 , 104 , 124 (“To feel like I have everyone following me around, whether it's negative or positive, that alone is a force of power… knowing that you can influence people's mind in the right way” 144 ), or with Truman‐like 49 , 72 delusions 85 , 145 (“I deduced that I had been on a secret TV show all of my life, similar to the Truman Show” 49 ) (see Figure 3).

Losing agency and control of the boundaries between the inner subjective and the outer world

In the Anastrophe stage, the individual's sense of agency and control over the delusional belief is lost (see Figure 3): “As my delusional system expanded and elaborated, it was as if I was not ‘thinking the delusion’: the delusion was ‘thinking me’!” 60 ; “My paranoid delusions spun out of control. I was a slave to madness” 79 .

The experience of hallucinations dissolves the boundaries between the self and the surrounding world: “When I am psychotic, I feel as though my awareness is happening to me. It's a passive experience. I'm at the mercy of ‘my’ thoughts and ‘my’ perceptions of people” 139 . Individuals report single or multiple voices 100 , 104 , 146 , 147 , 148 , distorted sounds or whispers 149 or physicalized thinking 150 , visions 104 , 111 , tactile sensations of radiation 65 , electricity 151 or burning 149 on the skin (see Figure 3).

Some reported experiences seem to support phenomenologically‐informed models suggesting that hallucinations represent an organization of the inner dialogue 152 emerging from the ipseity disturbances described above 97 : “I avoid the use of ‘voice’ to describe what occurs in my thinking. Instead, I prefer to conceptualize these occurrences by saying it is as if I hear ‘voices’… It's difficult to really concretely define ‘voices’ for someone else. Sometimes it seems they serve as reminders of things I should or shouldn't do – doubts vocalized” 150 .

The sense of agency and ownership 153 and the boundaries of the self are particularly disrupted by commanding voices giving orders 104 , 139 , 146 , warnings 147 , insults 104 , soothing 104 , 150 (more rarely encouraging 66 ): “I felt trapped in a bewildering hole; felt like wreckage on a derailed and deranged alien train; felt like I was about to be destroyed” 64 . The emotional correlates of these experiences are ontological fear 78 , 89 and pervasive terror 84 , 126 , 139 (see Figure 3). The word “nightmare” 89 , 126 , 151 is often used to describe such intense anguish. A sense of entrapment is frequently reported 84 , 88 , 89 , along with feelings of guilt, embarrassment 66 , 103 , 151 and self‐blaming 111 , 154 (see Figure 3): “My shame at even hearing these words in my head ran deep, but I couldn't make them stop. I tried my best to suppress them, but they welled up like poison in a spring” 79 .

The experience of an increased permeability of ego boundaries or the blending of the internal and the external fields 78 , 155 , 156 , 157 is sometimes explicitly mentioned: “I lost my ego‐boundary which meant everything external and internal seemed like one blend” 156 (“transitivism” for Bleuler 53 , “loss of ego‐demarcation” for Jaspers 6 ).

A dramatic dissolution of the sense of self and devitalization

The dissolution of the sense of self, already present during the prodromal phase (see Figure 2), becomes more intense: “I had the feeling that I was dissolving and that pieces of me were going out into space, and I feared that I would never be able to find them again” 78 . Individuals feel different from the usual self 65 , 101 , 114 (“I felt distinctly different from my usual self” 114 ; “I am only a response to other people; I have no identity of my own” 158 ; “I am only a cork floating on the ocean” 158 ), split, divided or scattered into various pieces 57 , 63 , 78 (Jaspers’ loss of awareness of unity of the self, or ego‐consistency and coherence 6 ).

The disorder of the basic sense of self leads to a disruption of the feeling of “mineness” in relation to one's psychic or bodily activity (Jaspers’ awareness of activity of the self, or ego‐activity 6 ) and to experiences of deanimation or devitalization 159 (Scharfetter's 160 , 161 loss of awareness of being or existing, or ego‐vitality): “It was not me who was engaging in such behaviors. I was unaware of my actions, observing myself in the third person” 155 ; “I walk like a machine; it seems to me that it is not me who is walking, talking, or writing with this pencil” 122 ; “A feeling of total emptiness frequently overwhelms me, as if I ceased to exist” 162 .

The experience of dissolution of the self is more marked when the ego‐world boundaries are compromised by passivity phenomena involving feeling under the influence of external forces 114 , 155 ; thoughts being read, inserted or broadcast 88 , 114 , 163 (see Figure 3); body boundaries being violated by entities or forces (“Someone cut open my head and inserted a bag”, “Areas of the body where forces enter” 164 ) or parts of the body being displaced (“Mouth was where hair should be”, “Arms sticking out of chest” 164 ). Some individuals may even feel that their body or parts of it are projected beyond their ego boundaries into outer space (“Arms disjointed from the body”, “Legs and arms dropped off” 164 ). Altered corporality experiences such as the disembodiment or distancing from one's own body or mental processes 157 often co‐occur, sometimes leading to somatic delusions 78 , 110 , 112 (see Figure 3): “I thought my inner being to be a deeply poisonous substance” 78 .

These experiences are often associated with the sense of the world turning into an unfamiliar place 57 , 65 , at times chaotic and frightening 57 , which can resolve in apocalyptic beliefs about incoming wars 65 , 89 or the inevitable end of the world 88 , 110 , 112 , or nihilistic delusions 114 , 155 : “I had the distinct impression that I did not really exist, because I could not make contact with my kidnapped self” 114 .

The dissolution of the self can result in extreme self‐harm behaviors: “When one's ego dissolves, it becomes a part of everything surrounding him; but at the same time, this unification entails the annihilation of the self – hence the suicidal ideation” 155 .

Feeling overwhelmed by chaos or noise inside the head

The disorganization of thoughts is a prominent experiential theme 66 , 84 , 108 , 163 , 165 (see Figure 3): “My head is ‘swarming’ with thoughts or ‘flooding’. I become overwhelmed by all the thinking going on inside my head. It sometimes manifests itself as incredible noise” 139 . Words such as “rollercoaster” 124 , “whirlwind” 114 , “vertigo” 79 or “maelstrom” 5 are used by individuals to try to convey an experience of inner chaos and confusion, which is difficult to articulate accurately through language 151 (see Figure 3): “Being in a whirlwind is not a very good metaphor for that experience, but I have trouble finding words to describe it” 114 .

As one individual describes, thought disorder can be experienced as a “weakening of the synthetic faculty”. “My thoughts seemed to have lost the power to squeeze things to clear organization” 84 . The weakening of the natural “core self” that organizes the meaning and significance of events 166 can lead to a disturbed “grip” or “hold” on the conceptual field 97 .

Losing trust and withdrawing from the world

During the first episode of psychosis, individuals frequently report losing trust in others (see Figure 3): “While I was in hospital, I was frightened, but at the same time I felt safe. I knew the workers were there to help me, but I just couldn't trust anyone” 66 .

Persecutory delusions disrupt the atmosphere of trust that permeates individuals’ social interactions and familiar environments 167 : “For me, it was about losing trust to everyone” (personal communication during the workshops). The loss of trust extends to the individual's immediate social network, with suspiciousness towards neighbors, family members, friends or colleagues 78 , 92 , 95 , 107 : “I was afraid of people to the extent that I wouldn't come out of my room when people were around. I ate my meals when my family was either gone or asleep” 78 .

A sense of helplessness 101 , 155 can be associated with these experiences: “You feel very much alone. You find it easier to withdraw than cope with a reality that is incongruent with your fantasy world” 111 . Therefore, the first episode is lived as an intensely isolating and solipsistic experience 60 , 101 , 111 , 155 (see Figure 3): “Having no friends to visit and living alone in my apartment… I began to spend weekends sitting on the couch all day” 147 . Individuals frequently withdraw (Figure 3) from family and friends 66 , 147 , college or school 79 , 88 , adopting a reclusive lifestyle 104 .

Withdrawal from social life is often associated with the subjective inability to cope with the disrupted sense of self and the world 5 , 111 , the loss of pleasure and interest in social relationships 66 , delusion‐fueled fears 78 , 104 , increasing difficulties in understanding social interactions 79 , or communication difficulties 58 , 91 , 101 , 114 : “I thought that I must be in hell and that part of the meaning of this particular hell was that no one else around understood that it was hell” 78 .

Relapsing stage

Grieving a series of personal losses

“At the time, my diagnosis was equal to the death sentence. Nothing could have been more devastating. Not even death itself” 62 . During the relapsing phase of psychosis, individuals are frequently confronted with a series of losses, leading to an experience of grief for their pre‐psychotic self 124 , 168 (ego‐identity 6 ) that impacts their confidence and self‐esteem 102 , 169 , 170 (see Figure 4): “It's hard to recall the past. Hard to accept things will be like this from now on” (personal communication during the workshops).

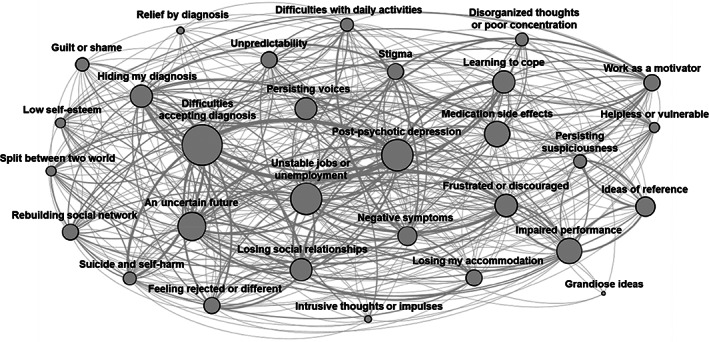

Figure 4.

Network map of lived experiences of psychosis during the relapsing stage. The nodes represent the experiential themes, and the edges represent the connections between them. The size of each node reflects the number of first‐person accounts addressing that experiential theme. The thickness of the edges reflects the number of connections between the themes.

These losses frequently include their past identities, as individuals often feel that they have to assume the new role of “mental patient”: “I entered the hospital as Robert Bjorklund, an individual, but left the hospital three weeks later as a ‘schizophrenic’” 171 . Individuals also grieve their individuality 65 , 171 , as they feel different compared to others 133 : “At first, it made me think that I was weird and different from everyone else. I didn't like feeling that I wasn't a part of the main group of people in life who were healthy and/or “normal” 156 .

Public stigma 94 , 156 , 170 , 172 , 173 towards mental disorders fuels feeling of rejection 50 , 56 , 126 , 156 , 174 , further reducing social networks 50 , 66 , 101 , 130 , 169 , 174 , 175 and personal relationships 105 , 107 , 156 , 169 , 173 (see Figure 4): “People would constantly joke about mental illness, and it was difficult for me to deal with” 172 . As a result, individuals typically hide their diagnosis 92 , 94 , 102 , 156 , 173 , 174 , 176 : “I struggled with accepting the diagnosis, and I never told anyone about it” 156 .

Another personal grief is for the premorbid sense of autonomy, as even the most mundane activities can now represent enormous challenges 89 , 94 , 102 (see Figure 4): “Something as basic as grocery shopping was both frightening and overwhelming for me. I remember my mom taking me along to do grocery shopping as a form of rehabilitation… Everything seemed so difficult” 94 . Difficulties in completing daily activities, performing at school or work 57 , 58 , 78 , 102 , 110 , 175 , 176 , 177 and maintaining employment 47 , 57 , 94 , 95 , 101 , 110 , 114 , 124 , 174 trigger sentiments of frustration and discouragement 47 , 57 , 59 , 101 , 102 , 169 , 177 (see Figure 4).

Individuals also mourn the loss of the sense of meaning or purpose that psychotic symptoms provided during the “aha” and Apophany phases 132 , 133 : “In my delusions, I had been a heroine on a mission; now that I was back on medication, I spent most of my days lying in bed, hating myself with a vengeance. Grief? Who knows?” 133 . Commonly, individuals struggle with post‐psychotic depressive mood following the remission of acute symptoms 101 , 108 , 112 , 132 , feeling “flawed” 94 by a lack of accomplishments 169 , leading to feelings of hopelessness and fragility 178 or the belief of being a “failure” 94 (see Figure 4).

Feeling split between different realities

Following remission of florid symptoms, individuals can feel “split” between the outer world and the private delusional worlds 78 , 155 , 176 (see Figure 4): “A constant during most of these years under psychiatric care and in the three years leading up to them was the existence of an inner reality that was more real to me than the world's outer reality” 78 ; “The difference between normal reality and psychosis feels extraordinarily subtle. It can, in its subtlety, encroach on me without my even noticing… That's why, today, I have a healthy respect for the cunningness of psychosis” 139 . Individuals can also feel split about the diagnosis and the need for ongoing medication: “I find it difficult to accept the continued professional opinion that I should take medication for my ‘condition’ over the long term” 107 .

This phenomenon of “double awareness” 179 , in which the person continues to simultaneously live in two realities 98 (i.e., the real and the delusional world), was originally referred to by Bleuler 53 as “double‐entry bookkeeping”.

An uncertain future

Following remission of acute psychosis, individuals face the task of rebuilding their identities and goals 124 , 154 , 169 : “Eventually, as discharge from my two years of treatment drew close, I was asked the big questions. What did I want to do now?” 154 . In this context, a psychotic relapse can be interpreted as a threat or even the complete abolition of a person's goals and future. Individuals can feel that past aspirations and plans in life are now completely out of reach 94 , 127 , 177 : “In my eyes, my life was over. Everything I had dreamt of doing, and all my aspirations in life, were now nonexistent. I felt completely nullified” 66 .

The sense of uncertainty is enhanced by the lack of a clear roadmap ahead: “That's what getting out of schizophrenia is like: there are no clues, no map, no road signs like ‘wrong way’, ‘turn here’, ‘detour’, ‘straight on’. And it's dark, lonely, and very frightening. You want nothing to do with it, but your return to sanity is at stake” 139 . The unpredictable evolution of the disorder also contributes: “However, now what I want more than anything else is to be sure that the things that I went through will never happen again. Unfortunately, that is not an easy thing to guarantee” 46 .

The acceptance of the diagnosis and the related uncertain future typically begins during this stage, but often requires several years of inner struggles 66 , 88 , 92 , 139 , 156 .

Chronic stage

Coming to terms with and accepting the new self‐world

During the chronic stage of psychosis, individuals often report feeling more optimistic about the future or believing that the worst is now behind them 47 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 78 , 91 , 94 , 95 , 101 , 124 , 129 , 150 , 170 , 177 (see Figure 5): “After more than 40 years of psychosis, I can now say, I feel better than I have ever felt in my life” 95 . Individuals may also report feeling more satisfied with their occupational activities than before 47 , 49 , 50 , 59 , 62 , 78 , 82 , 91 , 101 , 112 , 129 , 133 , 173 , 177 , 180 , 181 (see Figure 5).

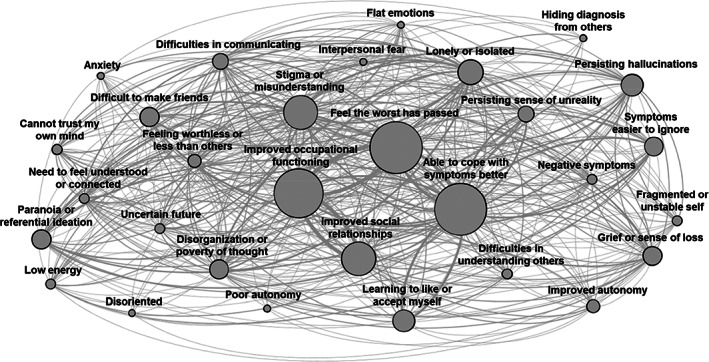

Figure 5.

Network map of lived experiences of psychosis during the chronic stage. The nodes represent the experiential themes, and the edges represent the connections between them. The size of each node reflects the number of first‐person accounts addressing that experiential theme. The thickness of the edges reflects the number of connections between the themes.

As the intensity of psychotic symptoms and the associated distress frequently decrease 127 , 147 , they can be more easily dismissed (see Figure 5): “I go out among people almost every day and, although I still feel ‘stared at’ and occasionally talked about, I do not believe, even if I am psychic, that I am an agent of God” 91 .

During this stage, individuals have often also learned how to cope more effectively with their symptoms, for instance ignoring the voices and delusional ideas, partially regaining a sense of agency or control 50 , 112 , 127 , 150 (see Figure 5): “I think the quality of the thought‐voices evolved as my health evolved. I no longer hear suggestions to run into traffic; if I did, I would refuse. I'm able to judge the appropriateness of the advice” 150 .

All this aids the individuals to come to terms with the diagnosis and its impact: “At 42, I think I'm slowly getting better or at least getting better at dealing with the difficulties that remain. I feel stronger and more stable now than ever before” 58 . Acceptance of psychosis and the new self 60 , 150 , 169 , 170 , 180 , 182 , 183 is a slow process that typically takes several years: “For a long time I searched for a lesson from my experience. What I learned was to build a new life and new dreams based on what I find myself capable of doing today” 89 .

However, a sense of grief and loss for the old self and the life before the disorder can still persist 124 , 133 , 150 , 168 , 175 , 184 : “Though I am working again, I have a pervading sense of loss about my life. This illness has affected all aspects of how I perceive myself and how others perceive me” 184 . This is accentuated when the individuals with lived experience of psychosis compare themselves with healthy peers 108 , feeling worthlessness or inferior 124 , 133 , 185 , 186 (see Figure 5).

Persisting inner chaos not visible from the outside

An unstable sense of self and the world can persist in this stage: “The clinical symptoms come and go, but this nothingness of the self is permanently there” 157 . These experiences can include an ongoing sense of unreality of the world 58 , 155 and disorientation 139 , 157 , and disorders of the sense of the self, such as devitalization, disintegration or disconnectedness 155 , 157 , 185 , loss of agency 149 , 187 , and fear of doing something that might have negative consequences 103 , 139 (see Figure 5).

A tumultuous inner world may be described, even if it is not “visible” from the outside 5 , with a constant feeling on edge from slipping away from reality: “Although on the outside things seem to have calmed down greatly, on the inside there is a storm raging, a storm that frightens me when I feel that I am alone in it” 5 . The experience may be aggravated by the feeling of not being able to trust one's own mind 5 , 185 , 188 (see Figure 5).

Loneliness and a desperate need to belong

While some improvements in socialization may be reported 47 , 49 , 50 , 82 , 101 , 114 , 127 , 133 , 175 , 180 , 181 (see Figure 5), social relationships tend to remain a major concern during the chronic stage of psychosis 63 , 112 : “I look at people, and I don't feel like one of them. People are strangers” 185 .

Pervasive feelings of loneliness and isolation 63 , 112 , 133 , 168 , 181 , 183 , 185 , 186 , 188 , including feeling “cut off from humanity” 185 , are commonly reported, and have been confirmed at meta‐analytical level 189 . There is often a strong and desperate call to feel understood, connected and accepted 5 , 133 , 185 (see Figure 5): “I need people to accept me enough to want to build a relationship with me… I feel cut off, cut off from humanity… I am already separated… I isolate myself on purpose because when I'm around others, that chasm between me and the world gets more pronounced; at least when I am alone, I can pretend I'm normal” 185 .

This desire for human warmth and closeness can be frustrated by equally intense fears of reaching out to people 5 , difficulties in communicating with others 185 , and not being able to convey the nature of psychotic experiences 5 , 58 (see Figure 5): “The more I try to speak, the less you understand me. This is why we stop trying to communicate… Not being able to communicate my basic feelings, not identifying with another human being, and feeling completely alone in my experience are killing me” 185 . Stigma and misunderstandings about mental disorders 58 , 110 , 133 , 139 , 168 , 173 , 180 , 184 , 186 , 188 , 190 and feelings of shame 185 amplify the experience of loneliness 49 , 173 (see Figure 5).

Difficulties in establishing and keeping social relationships 108 , 112 reiterate a weak attunement to the shared world of “unwritten” codes of social interactions (see Figure 5) 187 : “Making friends is pretty much a mystery to me. Even though I have made some friends in my life, I cannot seem to master or understand the skill” 188 . Individuals express this hypo‐attunement to the social world with statements such as: “I cannot associate with other persons”, “I always felt different, as if I belonged to another race”, or “I lack the backbone of the rules of social life” 191 .

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF RECOVERY AND OF RECEIVING TREATMENTS FOR PSYCHOSIS

This section explores the lived experience of recovery and of receiving treatments for psychosis. As the latter is determined by the type of care delivery platform and contexts, we first address the subjective experiences of receiving treatments across different mental health settings and subsequently focus on specific treatments. To reflect the multitude of possible experiences, we emphasize both core positive and negative aspects.

Recovery as a journey towards meaningful goals

Individuals feel that recovery extends beyond symptomatic improvement 192 (“It is not necessarily the disappearance of symptoms” 101 ), but rather is about achieving a sense of subjective control and being able to “do something about it” 193 : “Recovery to me means that, even if the delusions are not completely gone, I am able to function as if they are” 72 . Notably, “The road of recovery is totally different for each person and different in each stage and across different ages” (personal communication during the workshops).

Recovery from psychosis is commonly experienced as a cyclical and ongoing process that requires active involvement 94 , and is hardly ever “complete” 194 . This recovery “journey” 133 , 192 is filled with back‐and‐forth, rather than being a linear path with a set endpoint: “a long, solitary journey, with almost as much shock and fear at its outset as with the psychosis” 133 . It is, therefore, a dialectical process on its own. Or, as described in another account: “Recovery can be a process as well as an end… Recovery means finding hope and the belief that one may have a better future. It is achieving social reintegration. It is finding a purpose in life and work that is meaningful. Recovery is having a clear direction” 101 .

In more practical terms, recovery appears as a deep and protracted struggle to restore meaning and one's sense of self and agency 193 , 195 , 196 , re‐establishing an active relationship with the world 83 , 183 : “As I recover, I am also faced with rebuilding my identity and my life. Making the decision to end my career profoundly affected my sense of identity and self‐worth, and I have been left since searching for meaning and for a means by which I can continue to help others” 183 . As such, recovery is often understood by individuals as the ability to move towards meaningful goals 94 , 183 , 197 : “Recovery for me means serving a purpose; I think it is important for me because I felt ‘useless’ when I struggled through psychosis” (personal communication during the workshops).

The recovery process also involves a strengthening of the person's ego‐identity by building a sense of continuity with the past and a projection towards the future. Following a first episode, some young people view recovery as going back to their old selves, to “the way I was” 195 . For others, the recovery process requires a personal transformation of their identity and goals 183 and the acceptance, not only of the disorder 193 , but also of one's limitations: “For me, recovery has been about admitting something is wrong, about acknowledging my limitations. Recovery language focuses on what the person can do; I had to look at what I couldn't do before I could start to get better” 185 . A such, recovery is not necessarily about returning to the “past self” 192 , but implies assimilation of the experience into a new sense of self and a transformed understanding of the world and the person's role in it 83 .

Some young people feel that the recovery experience lead them to mature or make essential changes in their social relationships 195 , 196 , 198 . Psychosis can also provide new perspectives on life and relationships, including insights into one's life history 183 , increased empathy towards others 94 , 124 , 172 , or a rebalancing of life's priorities 56 , 101 , 169 : “I have more empathy for others and have a deeper understanding of what the human body is capable of. These components that make up my reality, to me, are the essence of life” 66 .

Supportive relationships are critical facilitators of the recovery journey: “The key to recovery for me was having really good supporting relationships that didn't break when everything else was breaking” (personal communication during the workshops). A relationship is perceived as helpful when it transmits hope for the future 58 , 94 , 105 , 177 , 197 , 199 : “Most importantly, my care team believed in the certainty of my recovery in a period of life when I just wasn't able to” 126 . Supporting relationships also facilitate understanding of the unusual experiences 6 , 200 , 201 in the context of compassionate 139 , 202 and positive attitudes 150 , and realistic expectations 203 .

The lived experience of receiving treatments across different health care settings

Inpatient care: a traumatic experience or a respite

“The attendants carried me into the dark corridor. A jumble of voices bounced off the walls – harsh bellows, still murmurs, and authoritative orders – but to me, the sounds blended together in a common senselessness” 48 . Admission to a hospital commonly occurs in the context of fear, chaos and confusion 48 , 66 , 84 , fuelled by delusional ideas 49 , 124 , 182 .

Negative experiences of being admitted to inpatient wards can trigger a sense of isolation 132 , hopelessness and uncertainty for the future 49 , 66 , 204 : “I wondered if I was ever going to recover; I wondered if I was ever going to be normal” 66 , and are often more pervasive for young people who are inappropriately admitted to adult mental health services 205 : “There were only a few younger ones in their twenties or thirties… I had heard someone use the term "chronic wards"… It didn't sound like a nice term” 48 .

The subjective experience of compulsory treatment or physical restraint during inpatient care is typically recalled as traumatic: “The first time was very traumatic… I refused medication, and I was held down and injected by six staff. What I feel strongly about is that no one gave me a choice… [this] added to the trauma that I'd already experienced in my home, being yanked out to an ambulance… It was a very nasty experience" 206 . The experience is associated with feeling powerless 108 and lacking privacy 207 , which can be re‐traumatizing for those with previous histories of abuse 206 .

A perceived “lack of compassion” 208 from the staff can lead to a sense of being “dehumanized” 209 : “‘Noncompliant’, passive dependent, passive‐aggressive… they all mean the same thing: you're not really you” 209 . Negative experiences of inpatient care can discourage future attempts to seek help 84 , 151 , 204 and hamper long‐term trust in the health care system: “I think if you don't come out and get a good experience right after that, then that's how you perceive the whole system” 208 .

However, in other cases, hospitalization can bring a much sought‐after sense of safety and relief, particularly during acute psychosis 66 , 78 , 114 : “The hospital was a safe haven” 210 . Hospitalization can also alleviate the personal exhaustion which follows the efforts to maintain a semblance of normalcy: “It was a relief to be in a place where it did not matter if you went off somewhere in the middle of a conversation. It was a relief not to have to fight all the time to maintain a semblance of sanity… It was a relief to be able to be honest” 78 .

The hospital can therefore provide a “respite” from the stress of life outside 205 , at times providing opportunities for recreation and the incorporation of healthy habits 66 , 108 , as well as time to reflect on the past and plan for the future: “It gave me a chance to think about what I really wanted to do with my life. I no longer wanted to continue working at a dull job where I was unhappy… There should be more to life” 57 .

Following discharge, the hospital can remain a safe haven to go back to during times of distress: “At those points in my life, the safety (albeit restrictive safety) offered by an institution was preferable to the responsibilities I felt I could not handle outside” 211 . As such, individuals can develop an ambivalent relationship with hospitalization, given the mixture of negative and positive experiences, especially when compulsory treatment was involved: “It would be a while before I realized hospital was there to help me in crisis rather than to further torture me as the voices had threatened” 84 .

Social relationships in the ward may have a solid positive impact on the subjective experience: “I found the staff usually kind, competent, and extremely tolerant of me and my fellow patients” 211 . Positive experiences are also linked to opportunities for in‐ward socialization that counter the sense of isolation 48 , 132 , 172 , 199 . For some individuals, the ward experience provides support networks that can persist after discharge: “Being in hospital is a painful experience, but it's also a personal journey, and for me, it was forming friendships on the ward that pulled me through (and continues to do so)” 172 .

Preventive and early intervention services: promoting and restoring hope

The subjective experience of individuals accessing specialized preventive (e.g., clinical high‐risk) or early intervention services for psychosis is markedly different compared to standard inpatient units. These services provide specialized and youth‐friendly care during a clinical high‐risk state or first episode of psychosis 34 , 212 , 213 . Their focus on recovery is greatly valued by young users 214 , 215 , 216 : “They get me more active. They encourage me to be interested in things and think that I have a future. I thought my life was coming to an end and they kind of encouraged me to see that there is life after psychosis” 216 .

Individuals value the support with everyday practical challenges – such as social relationships, employment and housing – suited to their actual needs and concerns 215 , 216 , 217 , provided by these services. In addition, when services are located within a youth‐friendly setting outside the “mainstream” psychiatric institutions, they are perceived to reduce the feeling of shame and self‐stigma often attached to accessing mental health care 217 , providing a “human touch” 214 and high quality of relationships with the care team that are key in the recovery process 208 , 215 , 216 , 217 , 218 .

In particular, individuals appreciate the opportunity to be involved as “partners” in the treatment decisions, as well as the experience of being treated “as a human being” 214 , 217 , since staff “listen and ask your opinion” 214 , while at the same time being allowed to “describe what I was experiencing” with their own words, rather than over‐relying on diagnostic labels 208 .

In addition, availability of staff 214 , 216 and continuity in care 216 , 218 are emphasized as positive aspects: “I was seeing my key worker every week or two, which was very good” 218 . Continuity in care has been highlighted as a key trust‐enhancing factor 219 : “Opening‐up to the therapist requires trust; it takes time to build up that relationship” (personal communication during the workshops).

Young users also value how these services support them in developing a positive sense of self by sharing their experiences with others 216 , 217 , 218 : “I've met quite a few people with similar problems to me, and it's helped because we've discussed how we're different and tried to suggest ways that can sort of help each other or help ourselves” 216 . Preventive and early intervention teams also provide a sense of certainty and safety 215 , 216 : “This is what I've been looking for, somebody who actually knows what they're talking about” 220 .

For young individuals at clinical high‐risk of psychosis, specialized care provides an opportunity to disclose the distressing experiences often kept hidden from family, friends and professionals. Understanding can emerge through a process of shared exploration and creation of links 221 between symptoms and life experiences: “This ‘normalization’ of my difficulties was one of the most helpful elements of therapy, as it very quickly reduced my fear of being ‘mad’, which had been the most disturbing of my worries” 222 .

On the other hand, discontinuity of care due to high staff turnover, whenever present, is felt like an essential source of frustration also within these services, as “it takes a whole load of time to build up trust in someone” 218 . Furthermore, following symptomatic and functional improvements, individuals can gradually lower their engagement with preventive or early intervention services, that are perceived as an unnecessary and undesired reminder that they are under mental health treatment 218 , 220 : “As I've got better, it's not nice having somebody come in all the time, because it constantly reminds you that you're suffering from an illness” 218 .

Outpatient care: opening the gates to the community

In the lived experience of persons with psychosis, practical and accessible outpatient services promote autonomy and control: “You can come for the treatment, and the gates are open for you to come” 223 , as well as fostering the sense of feeling welcomed: “It gives you an idea of home, it does not have that mystification that it is that closed, trapped thing and that you are hospitalized behind closed bars” 223 . As a result, the experiences of receiving outpatient community care can provide an opportunity for strengthening social bonds and networks.

Friendly and easily accessible outpatient multidisciplinary teams are perceived of utmost importance to achieve this: “I feel good, this is a family, if I'm not feeling good, they reach out for me. So here I found the people that really helped me. Every single one of them, from the cleaning mister to the service coordinator" 223 . These positive experiences are also crucial for promoting treatment adherence: "What gets me here is fraternity… They gave me so much fraternity that I end up saying to the doctor that out there, in my first life, second life, third life and present life I never had as much fraternity as I'm having here, I'm not drooling, it is the truth" 223 .

On the contrary, negative experiences of outpatient care result from fragmented services that expose users to repeated assessments and excessive waiting lists due to inter‐professional miscommunication 126 , 224 . Individuals often feel struggling with ever‐changing care teams and limited appointment times that are not enough for professionals to get to know them beyond the diagnostic label: “The various mental health professionals I saw at three separate psychiatric hospitals reinforced my narrowly defined diagnosis. Little effort was made to look beyond the many incongruences of my condition” 171 . In addition, the competing theories about psychosis can cause confusion, as individuals can feel as if “[clinicians] see what they want on your psychosis” (personal communication during the workshops).

The impersonal nature of some services can lead to an amplification of the inner feeling of objectification characterizing the experience of psychosis: “If you enter the psychiatric business as a patient, then you have a high chance of being reduced to a disturbing object or to the disorder itself. Only that which is significant to the diagnostic examination is seen and heard. We are examined but not really seen; we are listened to but not really heard” 65 . As a result, excessively bureaucratic clinical settings foster stigma and isolation 209 .

Individuals may also feel rejected by the service due to lack of expertise among staff: “There are no guidelines to do that” 65 . Additionally, outpatient services can be perceived as insufficient in their treatment offers when there is a narrow focus on one‐size‐fits‐all approaches 214 .

The lived experience of receiving specific treatments for psychosis

Social interventions: finding one's own space in the world

“I finally felt independent again. I was beginning to manage my mental illness. I was responsible again for my own space in the world” 225 . Social interventions are perceived as supporting individuals in rebuilding their disturbed sense of self by fostering autonomy and independence 96 . As previously discussed, one core component of psychosis is the disruption of the person's natural engagement with the world. Following a first episode, young individuals often view their recovery as being able to feel “normal” again 195 , which essentially means reintegrating into society 192 , re‐entering the workforce or going back to study in socially valuable roles 193 . Therefore, they feel that interventions supporting their study or work help them in regaining their sense of purpose 177 , 202 and confidence 226 : “I waged this war not because I am so brave but because I absolutely had to in order to keep my job” 170 .

Interventions supporting an independent housing are also key in the process of strengthening personal agency, fostering stability, autonomy and independence 224 , 227 : “Here [in the new house] I met new friends who accepted me. My attention shifted to pleasure and was increased through meeting new friends and enjoying the courses on offer” 202 .

Social interventions are also essential to reduce the experience of isolation and shame. This applies in particular to peer‐support groups 180 , which “normalize” the psychotic experiences 208 , 217 , allowing the affected individuals to feel “liberated” and hopeful: “They just told me that the fact was, there are other people like you, and you can get better from it” 217 . Peer‐support groups also help individuals to feel connected 228 and more accepted 184 : “[The peer‐support group] allows people to share their experiences, rediscover their emotions, and prepare for new journeys… where we can all support each other toward the goal of recovery and a better life” 228 .

Social interventions are also felt as helpful to overcome the passive role of affected individuals, stimulating a more proactive engagement in their care: “I feel less like an outsider and more like someone with something to offer” 229 . The positive experience of receiving these interventions is enhanced by the dialogic co‐responsibility of the partnership established across various social actors, involving the community and the family 230 .

The negative aspects of the experience of social interventions occur when the personal values of affected individuals are not prioritized, becoming purposeless 186 : “Occupational therapy was supposed to engage me in what the professionals deemed meaningful activity. So I painted, I glued, and I sewed. I was occupied, but where was the meaning?” 132 . These adverse experiences are widespread when individuals are asked or expected to conform and socially perform like everyone else: “I have to do things differently… It is unfair for others to expect us to finally finish that college degree and finally get that job… It makes us feel ashamed and hopeless and depressed” 185 .

Furthermore, people with chronic psychosis often point out that adequate community integration requires a delicate balance between socially‐promoting activities and having the space for solitary time 78 , 231 , 232 . This feeling has been confirmed by ethnographic studies, indicating that people with psychosis may develop a particular way of feeling integrated within society by keeping “at a distance” (i.e., neither too close nor too distant) 233 , 234 : “I need to be alone… If I were living in the countryside, nobody would care about my solitude, but in the city, no one is allowed to live like a hermit” 234 .

Psychological treatments: sharing and comprehending one's experiences

Psychological treatments are perceived as essential to provide the first channel to open oneself about difficult‐to‐communicate psychotic experiences 226 , 235 : “I wanted to learn to talk about my psychotic experiences, to communicate about them, and to learn to see their meaning” 65 .

For many individuals, recovery requires developing a complex and meaningful understanding of their distressing experiences, which re‐establishes a sense of continuity in their life narrative and overcomes the disturbances of the awareness of identity 65 , 183 , 193 , 196 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 : “Psychotic episodes don't happen out of nothing. There's always a reason for it. Unless the person is helped to make sense of that, they are not properly recovered” (personal communication during the workshops).

Given the intense search for explanations during the Trema phase of psychosis onset 240 , finding meaning through a shared collaborative process allows the individuals to feel understood by others 237 , reducing their sense of isolation and loneliness: “So powerful is this desire that I often speak fervently of the wish to place my therapist inside my brain so that he can just know what is happening inside me” 5 . However, not all individuals will necessarily succeed in discovering new meanings for their disorder: “I've never been good at the ‘finding meaning’ thing” (personal communication during the workshops).

The experience of receiving psychological treatments is valued when it flexibly allows individuals to experiment 241 different approaches and strategies: “My initial strategy for change was to take a break from the high‐stress activities that have historically triggered symptoms and to instead focus on ‘anchoring activities’ that I find personally meaningful, intellectually challenging, and conducive to ‘connectedness’ with others” 183 . Therefore, the experience of these treatments is highly personal, as reflected by the range of psychological coping strategies subjectively preferred, including improving mental health literacy and recognizing early warning signs 94 , 151 , 172 , 210 , self‐monitoring 151 , 197 , 242 , 243 , developing meaningful alternative activities 108 , setting a routine 63 , 108 , learning to interact with the voices 150 , 238 , reducing stress or “triggers” 46 , 180 , 183 , 244 , relaxation 151 , 202 or distraction 245 , 246 techniques, sharing and discussing the experience with others 82 , 150 , 172 , 242 , 245 , 246 , or employing reality‐testing and disconfirmation strategies 46 , 88 , 131 , 232 .

On the contrary, psychological treatments are felt unhelpful when they are “forced” upon the individual or deny his/her individuality 186 : “The person needs to identify what psychotherapy works best for them – what works for me does not necessarily work for someone else” (personal communication during the workshops). Poor attentive listening is also perceived as impeding the affected individuals to speak in their voice and share their meanings appropriately 247 . Moreover, during psychological treatments, individuals feel that voices should be balanced, with no dominant voice, even if there are different views 248 .