Abstract

Patient‐reported helpfulness of treatment is an important indicator of quality in patient‐centered care. We examined its pathways and predictors among respondents to household surveys who reported ever receiving treatment for major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, post‐traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, or alcohol use disorder. Data came from 30 community epidemiological surveys – 17 in high‐income countries (HICs) and 13 in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) – carried out as part of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Respondents were asked whether treatment of each disorder was ever helpful and, if so, the number of professionals seen before receiving helpful treatment. Across all surveys and diagnostic categories, 26.1% of patients (N=10,035) reported being helped by the very first professional they saw. Persisting to a second professional after a first unhelpful treatment brought the cumulative probability of receiving helpful treatment to 51.2%. If patients persisted with up through eight professionals, the cumulative probability rose to 90.6%. However, only an estimated 22.8% of patients would have persisted in seeing these many professionals after repeatedly receiving treatments they considered not helpful. Although the proportion of individuals with disorders who sought treatment was higher and they were more persistent in HICs than LMICs, proportional helpfulness among treated cases was no different between HICs and LMICs. A wide range of predictors of perceived treatment helpfulness were found, some of them consistent across diagnostic categories and others unique to specific disorders. These results provide novel information about patient evaluations of treatment across diagnoses and countries varying in income level, and suggest that a critical issue in improving the quality of care for mental disorders should be fostering persistence in professional help‐seeking if earlier treatments are not helpful.

Keywords: Helpfulness of treatment, professional help‐seeking, heterogeneity of treatment effects, patient‐centered care, treatment adherence, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, post‐traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, precision psychiatry

Mental and substance use disorders are highly prevalent worldwide. Conservative estimates indicate that approximately 20% of individuals meet criteria for a mental disorder within the past 12 months, with lifetime rates of about 30% 1 , 2 . Mental and substance use disorders are associated with marked distress, impairment in everyday life functioning, and early mortalitye.g., 3 , 4 , 5 . The economic costs of these disorders to individuals, families and society are enormous, encompassing lost income and productivity, disability payments, and costs of health care and social services 6 , 7 .

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have documented that a range of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments are effective in treating many people with mental and substance use disorders. Questions can be raised, though, about the generalizability of the results of RCTs, as these studies are mostly carried out in high‐income countries (HICs) and exclude patients with the complex comorbidities known to be very common in the real world.

In addition, outside the context of controlled trials, patients often seek multiple treatments over time and across multiple settings. RCTs do not provide information over the life course and the many different services patients seek over time. It is important to understand this process and whether it varies as a function of disorders.

Although symptom reduction is typically the primary and often exclusive focus of clinical trials, patients are known to have broader notions about what constitutes effective treatment 8 . It is essential to evaluate treatment effectiveness from the patient perspective in real‐world settings. A broad assessment of patient‐reported treatment helpfulness can be a useful first step in doing this, by allowing patients to provide an overall summary evaluation of how treatment has affected their well‐being and functioning in life domains important to them.

The likelihood of help‐seeking leading to a treatment that the patient considers helpful is a joint function of: a) the probability that a given patient will consider a specific treatment helpful and b) the probability that the patient will persist in help‐seeking if a prior treatment was not helpful. Population‐based surveys provide the opportunity to trace these two pathways over many patients, identify both aggregate distributions, and examine predictors of receiving patient‐defined helpful treatment, as mediated through these two pathways.

We carried out a series of disorder‐specific investigations that looked at the extent to which individuals view their treatment as helpful. The disorders included major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social phobia, specific phobia, and alcohol use disorder. These investigations were conducted in a cross‐national series of general population surveys that asked respondents about their lifetime experiences of seeking professional treatments. The samples were drawn from both HICs and low/middle‐income countries (LMICs). Prior reports focused on individual disorders 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 . We found that the great majority of people in the general population who seek treatment for mental disorders believe that they were helped. However, no one treatment was found to be helpful for all patients, and only a minority of patients reported that they were helped by the first professional from whom they received treatment. Perseverance was required to obtain treatment that patients considered helpful. However, substantial proportions of patients reported that they gave up their professional help‐seeking efforts before helpful treatment was received, even though many of these individuals continued to suffer.

The present study provided an opportunity to address new questions by looking at the data across all disorders. We had several goals: to estimate variation across disorders in the proportion of patients reporting that their treatment was helpful; to examine the number of professionals that patients needed to see to receive a treatment that they considered helpful; to examine persistence in professional help‐seeking among patients whose earlier treatments were not helpful; to estimate consistency across disorders of predictors of helpfulness at the patient‐disorder level; and to disaggregate the significant predictors into the separate associations predicting helpfulness of individual professionals and persistence in help‐seeking after earlier treatments not being helpful. It is plausible to expect differences across disorders because treatments are not equally available or effective for all disorders.

We also looked at variation between HICs and LMICs in reported helpfulness of treatment and persistence in help‐seeking, and tried to identify any common or unique factors that influence patient‐reported treatment helpfulness and persistence in seeking further treatments across disorders and countries. Information about variations of these sorts may be helpful in identifying where emphasis is most needed for developing more effective treatments and/or providing more readily accessible services.

METHODS

Sample

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys are a coordinated set of community epidemiological surveys administered to probability samples of the non‐institutionalized household population in countries throughout the world 16 .

Data for the present study come from 30 WMH surveys (Table 1). Seventeen surveys were carried out in countries classified by the World Bank as HICs (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, the US, and two in Spain). The other thirteen surveys were conducted in countries classified as LMICs (Brazil, Iraq, Lebanon, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, People's Republic of China, Romania, South Africa, and two each in Bulgaria and Colombia).

Table 1.

World Mental Health sample characteristics

| Sample size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Sample composition | Field dates | Age range | Part I | Part II | Response rate |

| High‐income | ||||||

| Argentina | Eight largest urban areas of the country (about 50% of total national population) | 2015 | 18‐98 | 3,927 | 2,116 | 77.3 |

| Australia | Nationally representative | 2007 | 18‐85 | 8,463 | 8,463 | 60.0 |

| Belgium | Nationally representative (selected from a national register of Belgium residents) | 2001‐2 | 18‐95 | 2,419 | 1,043 | 50.6 |

| France | Nationally representative (selected from a national list of households with listed telephone numbers) | 2001‐2 | 18‐97 | 2,894 | 1,436 | 45.9 |

| Germany | Nationally representative | 2002‐3 | 19‐95 | 3,555 | 1,323 | 57.8 |

| Israel | Nationally representative | 2003‐4 | 21‐98 | 4,859 | 4,859 | 72.6 |

| Italy | Nationally representative (selected from municipality resident registries) | 2001‐2 | 18‐100 | 4,712 | 1,779 | 71.3 |

| Japan | Eleven metropolitan areas | 2002‐6 | 20‐98 | 4,129 | 1,682 | 55.1 |

| The Netherlands | Nationally representative (selected from municipal postal registries) | 2002‐3 | 18‐95 | 2,372 | 1,094 | 56.4 |

| New Zealand | Nationally representative | 2004‐5 | 18‐98 | 12,790 | 7,312 | 73.3 |

| North Ireland | Nationally representative | 2005‐8 | 18‐97 | 4,340 | 1,986 | 68.4 |

| Poland | Nationally representative | 2010‐1 | 18‐65 | 10,081 | 4,000 | 50.4 |

| Portugal | Nationally representative | 2008‐9 | 18‐81 | 3,849 | 2,060 | 57.3 |

| Saudi Arabia | Nationally representative | 2013‐6 | 18‐65 | 3,638 | 1,793 | 61.0 |

| Spain | Nationally representative | 2001‐2 | 18‐98 | 5,473 | 2,121 | 78.6 |

| Spain (Murcia) | Regionally representative (Murcia region) | 2010‐2 | 18‐96 | 2,621 | 1,459 | 67.4 |

| United States | Nationally representative | 2001‐3 | 18‐99 | 9,282 | 5,692 | 70.9 |

| High‐income total | 89,404 | 50,218 | 63.0 | |||

| Low/middle‐income | ||||||

| Brazil (São Paulo) | São Paulo metropolitan area | 2005‐8 | 18‐93 | 5,037 | 2,942 | 81.3 |

| Bulgaria 1 | Nationally representative | 2002‐6 | 18‐98 | 5,318 | 2,233 | 72.0 |

| Bulgaria 2 | Nationally representative | 2016‐7 | 18‐91 | 1,508 | 578 | 61.0 |

| Colombia | All urban areas of the country (about 73% of total national population) | 2003 | 18‐65 | 4,426 | 2,381 | 87.7 |

| Colombia (Medellin) | Medellin metropolitan area | 2011‐2 | 19‐65 | 3,261 | 1,673 | 97.2 |

| Iraq | Nationally representative | 2006‐7 | 18‐96 | 4,332 | 4,332 | 95.2 |

| Lebanon | Nationally representative | 2002‐3 | 18‐94 | 2,857 | 1,031 | 70.0 |

| Mexico | All urban areas of the country (about 75% of total national population) | 2001‐2 | 18‐65 | 5,782 | 2,362 | 76.6 |

| Nigeria | 21 of 36 states (57% of national population) | 2002‐4 | 18‐100 | 6,752 | 2,143 | 79.3 |

| Peru | Five urban areas (about 38% of total national population). | 2004‐5 | 18‐65 | 3,930 | 1,801 | 90.2 |

| People's Republic of China (Shenzhen) | Shenzhen metropolitan area | 2005‐7 | 18‐88 | 7,132 | 2,475 | 80.0 |

| Romania | Nationally representative | 2005‐6 | 18‐96 | 2,357 | 2,357 | 70.9 |

| South Africa | Nationally representative | 2002‐4 | 18‐92 | 4,315 | 4,315 | 87.1 |

| Low/middle‐income total | 57,007 | 30,623 | 80.6 | |||

| Total | 146,411 | 80,841 | 68.9 | |||

Twenty of these 30 surveys were based on nationally representative samples (14 in HICs, 6 in LMICs), three on samples of all urbanized areas in the country (Argentina, Colombia, Mexico), three on samples of selected states (Nigeria) or metropolitan areas (Japan, Peru), and four on samples of single states (Murcia, Spain) or metropolitan areas (Sao Paolo, Brazil; Medellin, Colombia; Shenzhen, People's Republic of China). Response rates ranged from 45.9% (France) to 97.2% (Medellin, Colombia) and averaged 68.9% across surveys.

Measures

Interviews

The interview schedule used in the WMH surveys was the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 3.0 17 , a fully structured diagnostic interview designed to be used by trained lay interviewers. A standardized seven‐day training program was given to all WMH interviewers across countries. The program culminated in an examination that had to be passed before the interviewer could be authorized to participate in data collection 18 . The interview schedule was developed in English and translated into other languages using a standardized WHO translation protocol 19 .

Interviews were administered face‐to‐face in respondents’ homes after obtaining informed consent using procedures approved by local institutional review boards. Interviews were in two parts. Part I was administered to all respondents and assessed core DSM‐IV mental disorders (N=146,411 respondents across all surveys). Part II assessed additional disorders and correlates and was administered to 100% of respondents who met lifetime criteria for any Part I disorder plus a probability subsample of other Part I respondents (N=80,841).

Disorders

Although the CIDI generates diagnoses according to both ICD‐10 and DSM‐IV criteria, only DSM‐IV criteria were used in the analyses reported here. We considered seven lifetime disorders: major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder (including bipolar I, bipolar II and sub‐threshold bipolar disorder), four anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, social phobia and specific phobia), and alcohol use disorder (either alcohol abuse without dependence or alcohol dependence). We carried out separate analyses of patient‐reported treatment helpfulness for major depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes in bipolar disorder, so a total of eight diagnostic categories were considered.

A good concordance was found 20 between DSM‐IV diagnoses based on the CIDI and those based on independent clinical reappraisal interviews carried out using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV 21 . Organic exclusions but not diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making diagnoses. The CIDI included retrospective disorder age‐of‐onset reports based on a special question probing sequence that has been shown experimentally to improve recall accuracy 22 . In assessing age of onset, respondents were asked to date their age when they first met criteria for the full syndrome of each disorder, not the first symptom of the disorder.

Patient‐reported treatment helpfulness

Respondents who met lifetime DSM‐IV criteria for each of the eight diagnostic categories were asked about age of onset and “Did you ever (emphasis in original) in your life talk to a medical doctor or other professional about your…?” (wording varied across diagnostic categories). If the answer was yes, the interviewer went on to ask “How old were you the first time (emphasis in original) you talked to a professional about your…?” (same wording as prior question). The term “other professionals” was defined and presented to the respondent in a show card before asking this question as including psychologists, counselors, spiritual advisors, herbalists, acupuncturists, and other healing professionals.

Respondents who said that they had talked to a professional were then asked “Did you ever get treatment for your … (same wording as in prior question) that you considered helpful or effective ?” (emphasis in original). The next question then varied depending on whether the respondent reported ever receiving helpful or effective treatment. If so, the interviewer asked “How many professionals did you ever (emphasis in original) talk to about your… (same wording as in prior question) up to and including the first time you ever got helpful treatment?”. If, on the other hand, the respondent reported never receiving helpful or effective treatment, the interviewer asked “How many professionals did you ever (emphasis in original) talk to about your…?” (same wording as in prior question). We focused on respondents who reported treatment starting no earlier than 1990.

Predictors

We considered six different kinds of predictors of patient‐reported treatment helpfulness: focal diagnostic category, socio‐demographics, prior lifetime comorbidities, treatment type(s) received, treatment timing, and childhood adversities.

Focal diagnostic category was represented as a series of eight dummy‐coded predictor variables that allowed us to examine the significance of differences across the above‐mentioned categories in patient‐reported treatment helpfulness. Socio‐demographic characteristics included age at first treatment (continuous), gender, marital status (married, never married, previously married) at the time of first treatment, level of educational attainment among non‐students (quartiles defined by within‐country distributions), and student status at the time of first treatment.

Prior lifetime comorbid conditions included lifetime onset of each of the other seven diagnostic categories considered here prior to age at first treatment of the focus diagnostic category. We also included two other comorbid diagnostic categories involving substance use disorders (substance dependence and substance abuse without dependence). The substances considered in the latter assessment included both prescription medications (used without a prescription or more than prescribed) and illicit drugs. The precise substances included in the assessment and the names used to describe them varied across surveys in line with differences in the drugs used in the countries. We did not include substance use disorders among the focal diagnostic categories because too few surveys assessed treatment helpfulness for these disorders for analysis.

Treatment type was defined as the cross‐classification of variables for: a) whether the respondent reported receiving medication, talk therapy, or both, as of the age at first treatment; and b) types of professionals seen as of that age, including mental health specialists (psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse, psychologist, psychiatric social worker, mental health counselor), primary care providers, human services providers (social worker or counselor in a social services agency, spiritual advisor), and complementary/alternative medicine providers (i.e., other type of healers or self‐help groups).

Treatment timing included a dichotomous measure for whether the respondent's first treatment for the focal diagnostic category occurred before the year 2000 or subsequently, and a continuous variable for length of delay in years between age of onset of the diagnostic category and age at first treatment.

Childhood adversities were assessed by twelve questions about experiences that occurred before respondents were age 18 23 . Based on exploratory latent class analysis, dichotomously scored responses were combined into two dichotomous indicators of maladaptive family functioning adversities and other adversities. The maladaptive family functioning childhood adversities included four types of parental maladjustment (mental illness, substance abuse, criminality, violence) and three types of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect). The other childhood adversities included three types of interpersonal loss (parental death, parental divorce, other separation from parents), life‐threatening respondent physical illness, and family economic adversity. The questions about parental death, divorce, and other loss (e.g., respondent's foster care placement) included non‐biological as well as biological parents.

Analysis methods

The analysis sample was limited to people with first lifetime treatment of at least one focal diagnostic category during or after 1990. The dataset was stacked across the eight diagnostic categories. Information about the focal diagnostic category was included as a series of dummy‐coded predictor variables. Cross‐tabulations at the person‐visit level were used to examine conditional probabilities of: a) patient‐reported helpfulness of treatment by number of professionals seen and b) conditional probabilities of persisting in help‐seeking after previously receiving treatments that were considered not helpful. Standard discrete‐time survival analysis methods 24 were then used to calculate cumulative survival curves for probabilities of patient‐reported helpfulness and persistence across number of professionals seen.

Modified Poisson regression models for binary outcomes 25 were then estimated to examine baseline (i.e., as of age at first treatment) predictors of receiving helpful treatment at the patient level regardless of number of professionals seen. Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were exponentiated to obtain risk ratios (RRs). In the case of the indicator variable for focal diagnostic category, these RRs were centered to interpret variation across the categories. The product of these centered RRs across all diagnostic categories equals 1.0, allowing each individual RR to be interpreted as relative to the average across all categories.

The same link function and transformations were then used to decompose each significant patient‐level predictor to investigate whether the association of that predictor with the outcome was due to one, the other, or both of the two component associations: a) the association of the predictor with conditional RR of an individual professional being helpful; and b) the association of the predictor with conditional RR of persistence in help‐seeking after not previously receiving helpful treatment. Finally, interactions were estimated between diagnostic categories and each predictor to investigate the possibility of variation in predictor strength across disorders. Importantly, these interactions were examined one at a time rather than together, to avoid problems with model instability.

Weights were applied to the data to adjust for differential probabilities of selection (due to only one person being surveyed in each household, no matter how many eligible adults lived in the household) and differential non‐response rates (documented by discrepancies between the census population distributions of socio‐demographic or geographic variables and the distributions of these same variables in the sample). In addition, Part II respondents were weighted to adjust for the under‐sampling of Part I respondents without disorders. The latter weight resulted in prevalence estimates of Part I disorders in the weighted Part II sample being virtually identical to those in the Part I sample 26 .

Because of this weighting and the geographic clustering of the WMH survey designs, all statistical analyses were carried out using the Taylor series linearization method 27 , a design‐based method implemented in the SAS 9.4 software system 28 . Statistical significance was evaluated consistently using 0.05‐level two‐sided design‐based tests.

RESULTS

Disorder prevalence, treatment, and patient‐reported treatment helpfulness

The lifetime disorder prevalence in the total sample ranged from a high of 9.5% for alcohol use disorder (11.5% in HICs; 6.7% in LMICs) to a low of 1.2% for major depressive episode in bipolar disorder (1.3% in HICs; 0.9% in LMICs). The prevalence was consistently higher in HICs than LMICs (X 2 1=10.8‐398.0, p=0.001 to <0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence of the DSM‐IV disorders considered in the analysis, proportions of cases receiving treatment, and proportions of patients reporting that treatment was helpful

| Lifetime disorder prevalence | Respondents receiving treatment | Respondents reporting that treatment was helpful | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | |

| Major depressive disorder | |||||||||

| All | 8.8 | 0.1 | 80,332 | 37.2 | 0.7 | 7,448 | 68.2 | 1.1 | 2,726 |

| High‐income countries | 10.0 | 0.2 | 41,778 | 47.1 | 1.0 | 4,438 | 70.1 | 1.2 | 2,082 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 7.4 | 0.2 | 38,554 | 22.5 | 1.0 | 3,010 | 62.4 | 2.2 | 644 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | |||||||||

| All | 4.5 | 0.1 | 113,226 | 34.6 | 0.8 | 5,674 | 70.0 | 1.4 | 1,897 |

| High‐income countries | 5.3 | 0.1 | 76,775 | 38.4 | 0.9 | 4,617 | 70.9 | 1.4 | 1,701 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 2.8 | 0.1 | 36,451 | 19.2 | 1.8 | 1,057 | 62.8 | 4.9 | 196 |

| Social phobia | |||||||||

| All | 4.6 | 0.1 | 117,856 | 22.8 | 0.7 | 5,686 | 65.1 | 1.6 | 1,322 |

| High‐income countries | 5.9 | 0.1 | 71,916 | 24.8 | 0.8 | 4,538 | 65.9 | 1.7 | 1,148 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 2.5 | 0.1 | 45,940 | 15.8 | 1.3 | 1,148 | 60.4 | 5.1 | 174 |

| Specific phobia | |||||||||

| All | 7.7 | 0.1 | 112,507 | 13.7 | 0.5 | 9,179 | 47.5 | 1.8 | 1,296 |

| High‐income countries | 8.2 | 0.1 | 59,815 | 16.7 | 0.6 | 5,496 | 47.3 | 2.0 | 944 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 7.0 | 0.2 | 52,692 | 9.7 | 0.7 | 3,683 | 48.0 | 3.5 | 352 |

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||||||||

| All | 4.4 | 0.1 | 52,979 | 23.5 | 1.0 | 3,511 | 57.0 | 2.4 | 779 |

| High‐income countries | 5.3 | 0.1 | 37,422 | 26.4 | 1.1 | 2,906 | 57.6 | 2.4 | 726 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 2.3 | 0.1 | 15,557 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 605 | 43.8 | 9.2 | 53 |

|

Major depressive episode in bipolar disorder |

|||||||||

| All | 1.2 | 0.1 | 55,206 | 43.9 | 2.6 | 624 | 65.1 | 3.9 | 280 |

| High‐income countries | 1.3 | 0.1 | 36,919 | 47.9 | 3.0 | 481 | 64.6 | 4.2 | 235 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 0.9 | 0.1 | 18,287 | 31.9 | 4.8 | 143 | 67.3 | 9.3 | 45 |

| Mania/hypomania | |||||||||

| All | 2.3 | 0.1 | 91,416 | 26.6 | 1.3 | 2,178 | 63.1 | 2.4 | 598 |

| High‐income countries | 2.7 | 0.1 | 58,991 | 28.9 | 1.5 | 1,705 | 63.0 | 2.5 | 503 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 1.6 | 0.1 | 32,425 | 19.3 | 2.2 | 473 | 63.5 | 6.1 | 95 |

| Alcohol use disorder | |||||||||

| All | 9.5 | 0.1 | 93,843 | 11.8 | 0.5 | 9,378 | 44.5 | 2.3 | 1,137 |

| High‐income countries | 11.5 | 0.2 | 53,903 | 14.2 | 0.7 | 6,867 | 44.0 | 2.5 | 974 |

| Low/middle‐income countries | 6.7 | 0.2 | 39,940 | 6.4 | 0.8 | 2,511 | 46.8 | 5.3 | 163 |

| All diagnostic categories | |||||||||

| All | 23.0 | 0.3 | 43,678 | 61.7 | 0.7 | 10,035 | |||

| High‐income countries | 27.1 | 0.4 | 31,048 | 62.6 | 0.7 | 8,313 | |||

| Low/middle‐income countries | 13.8 | 0.5 | 12,630 | 57.6 | 1.9 | 1,722 | |||

SE – standard error

Roughly one‐fourth (23.0%) of respondents stacked across diagnostic categories received treatment, but this proportion was nearly twice as high in HICs as LMICs (27.1% vs. 13.8%, X 2 1=382.4, p<0.001). The proportion receiving treatment also varied significantly across diagnostic categories, both in the total sample (X 2 7=1402.0, p<0.001) and in the country income group sub‐samples (X 2 7=1308.6, p<0.001 in HICs; X 2 7=230.4, p<0.001 in LMICs). This variation was very similar in HICs and LMICs (Pearson correlation=.88), although consistently higher in HICs than LMICs (X 2 1=7.1‐261.0, p=0.008 to <0.001), from a high of 43.9% (47.9% in HICs; 31.9% in LMICs) for major depressive episode in bipolar disorder to a low of 11.8% (14.2% in HICs; 6.4% in LMICs) for alcohol use disorder.

Stacked across all diagnostic categories, 61.7% of patients reported being helped by treatment, with the proportion somewhat higher in HICs than LMICs (62.6% vs. 57.6%, X 2 1=6.4, p=0.012). The proportion of patients who reported being helped varied significantly across diagnostic categories, both in the total sample (X 2 7=189.6, p<0.001) and in the country income group sub‐samples (X 2 7=168.3, p<0.001 in HICs; X 2 7=25.73, p<0.001 in LMICs). This variation was very similar in HICs and LMICs (Pearson correlation=.80), from a high of 70.0% for generalized anxiety disorder (70.9% in HICs; 62.8% in LMICs) to a low of 44.5% for alcohol use disorder (44.0% in HICs; 46.8% in LMICs).

Differences between HICs and LMICs in the proportion of patients who reported being helped by treatment were non‐significant for all but one diagnostic category (X 2 1=0.0‐2.7, p=0.93 to 0.10). The exception was major depressive disorder, with a higher proportion of patients in HICs than LMICs reporting that they had been helped by treatment (70.1% vs. 62.4%, X 2 1=9.7, p=0.002).

Conditional and cumulative probabilities of treatment being helpful

Across all surveys and diagnostic categories, 26.1% of patients (N=10,035) reported being helped by the very first professional they saw (Table 3). This is less than half the 61.7% who reported being helped at all, indicating that most patients saw two or more professionals before they received treatment that they considered helpful.

Table 3.

Conditional probabilities of patient‐reported treatment helpfulness by number of professionals seen pooled across diagnostic categories

| Number of professionals seen | All countries | High‐income countries | Low/middle‐income countries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | |

| 1 | 26.1 | 0.6 | 10,035 | 25.4 | 0.7 | 8,313 | 29.2 | 1.4 | 1,722 |

| 2 | 34.0 | 1.0 | 5,261 | 33.6 | 1.1 | 4,530 | 36.2 | 2.9 | 731 |

| 3 | 32.2 | 1.4 | 2,705 | 32.3 | 1.6 | 2,329 | 32.0 | 3.3 | 376 |

| 4 | 26.2 | 1.9 | 1,454 | 26.2 | 2.1 | 1,260 | 25.8 | 5.0 | 194 |

| 5 | 24.3 | 1.9 | 876 | 25.1 | 2.1 | 766 | 19.2 | 3.8 | 110 |

| 6 | 24.7 | 2.8 | 539 | 24.8 | 3.1 | 483 | 24.2 | 5.7 | 56 |

| 7 | 17.8 | 2.8 | 360 | 18.0 | 3.0 | 321 | 16.5 | 7.3 | 39 |

| 8 | 17.9 | 4.1 | 277 | 19.1 | 4.4 | 248 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 29 |

| 9 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 222 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 198 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 24 |

| 10 | 31.5 | 4.5 | 208 | 34.5 | 4.9 | 187 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 21 |

| 11 | 16.8 | 5.4 | 95 | 7.9 | 3.8 | 81 | 56.9 | 13.8 | 14 |

| 12 | 15.1 | 4.2 | 82 | 16.7 | 4.6 | 73 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 |

| 13 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 63 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 55 | 10.3 | 2.3 | 8 |

| 14 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 59 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 52 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 |

| 15 | 22.9 | 8.4 | 58 | 25.8 | 9.4 | 51 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 |

| 16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 45 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 45 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 18 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 44 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 38 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 19 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 43 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 37 | 46.1 | 10.8 | 6 |

| 20 | 23.7 | 8.1 | 42 | 25.8 | 8.9 | 37 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 |

SE – standard error

Conditional (on persisting in help‐seeking after prior professionals not being helpful) probabilities of being helped were marginally higher for the second and third professionals seen (34.0‐32.2%) and then successively lower for the fourth to sixth (26.2‐24.7%) and seventh/eighth (17.8‐17.9%) professionals seen. Conditional probabilities became much more variable and generally lower for the ninth to twelfth professionals seen (averaging 10.7%). Differences between HICs and LMICs were for the most part non‐significant (see Table 3).

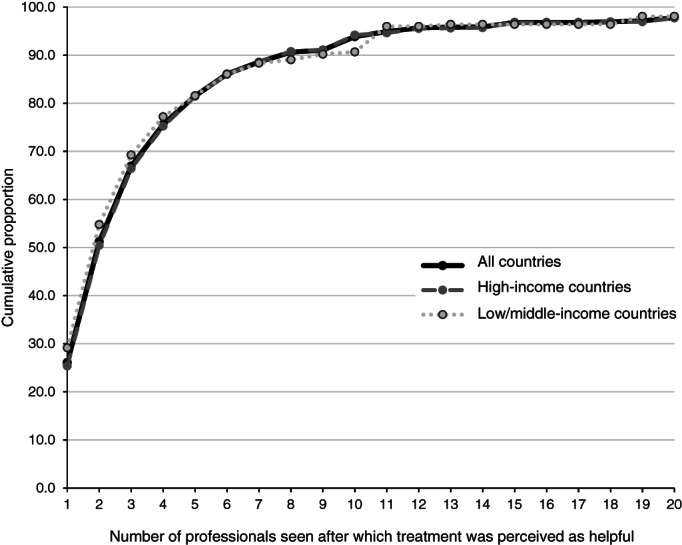

Survival analysis showed that cumulative probability of being helped rose to 51.2% among patients who persevered in seeing a second professional after not being helped by the first, to 66.9% after the third, 75.6% after the fourth, and rose to 90.6% after the eighth (Figure 1). Differences between HICs and LMICs were small and statistically non‐significant (X 2 1=2.4, p=0.12).

Figure 1.

Cumulative proportion of patients who would be expected to receive helpful treatment by number of professionals seen pooled across all diagnostic categories

Persistence in help‐seeking following prior unhelpful treatment

The last results make it clear that persistence in help‐seeking pays off. But, how persistent are patients in continuing to seek professional help after earlier unhelpful treatments? Across all surveys and diagnostic categories, 70.7% of patients who were not helped by an initial professional persisted in seeing a second (Table 4), but this proportion was significantly higher in HICs than LMICs (72.9% vs. 60.3%, X 2 1=40.9, p<0.001). Conditional (on prior professionals not being helpful) probabilities of persistence were even higher after seeing additional professionals, with generally non‐significant differences between HICs and LMICs (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Conditional probabilities of persistence in professional help‐seeking after previous treatments that were not helpful pooled across diagnostic categories

| Previous number of professionals seen | All countries | High‐income countries | Low/middle‐income countries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | |

| 1 | 70.7 | 0.7 | 7,382 | 72.9 | 0.8 | 6,179 | 60.3 | 1.8 | 1,203 |

| 2 | 75.5 | 1.0 | 3,524 | 75.2 | 1.1 | 3,030 | 77.3 | 2.4 | 494 |

| 3 | 80.4 | 1.1 | 1,823 | 80.8 | 1.2 | 1,564 | 77.8 | 2.7 | 259 |

| 4 | 81.2 | 1.8 | 1,079 | 81.6 | 2.0 | 937 | 78.8 | 4.1 | 142 |

| 5 | 82.7 | 1.8 | 644 | 86.6 | 1.8 | 563 | 60.7 | 6.1 | 81 |

| 6 | 87.4 | 2.1 | 408 | 87.4 | 2.3 | 364 | 87.9 | 6.0 | 44 |

| 7 | 90.6 | 2.3 | 305 | 93.1 | 1.9 | 270 | 71.5 | 11.5 | 35 |

| 8 | 94.1 | 3.4 | 233 | 93.8 | 3.7 | 207 | 97.1 | 2.7 | 26 |

| 9 | 97.7 | 1.0 | 213 | 97.5 | 1.2 | 192 | 100 | 0.0 | 21 |

| 10 | 66.7 | 5.7 | 135 | 63.5 | 6.4 | 116 | 85.4 | 8.0 | 19 |

| 11 | 98.2 | 1.3 | 84 | 98.0 | 1.4 | 75 | 100 | 0.0 | 9 |

| 12 | 84.0 | 8.5 | 68 | 83.7 | 9.5 | 59 | 86.2 | 10.7 | 9 |

| 13 | 99.3 | 0.7 | 60 | 99.2 | 0.8 | 53 | 100 | 0.0 | 7 |

| 14 | 100 | 0.0 | 58 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 51 | 100 | 0.0 | 7 |

| 15 | 97.7 | 2.0 | 47 | 99.6 | 0.4 | 40 | 86.2 | 12.2 | 7 |

| 16 | 100 | 0.0 | 45 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 39 | 100 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 17 | 91.8 | 7.7 | 45 | 90.6 | 8.8 | 39 | 100 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 18 | 100 | 0.0 | 43 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 37 | 100 | 0.0 | 6 |

| 19 | 100 | 0.0 | 42 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 37 | 100 | 0.0 | 5 |

SE – standard error

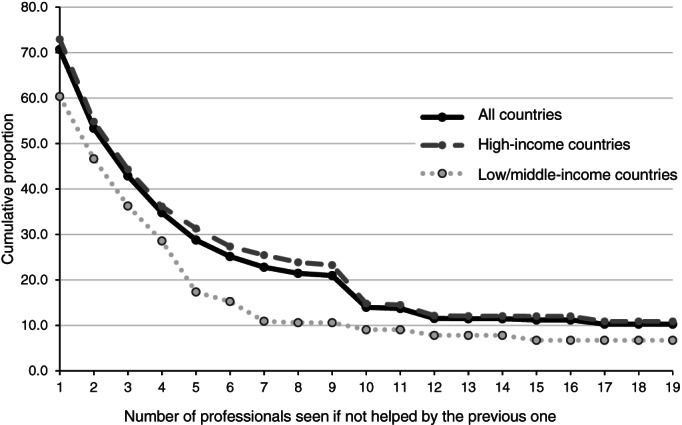

However, survival analyses showed that the cumulative probability of persistence in help‐seeking decreased markedly after continued unhelpful treatments (Figure 2) and significantly more so in LMICs than HICs (X 2 1=35.2, p<0.001). For example, only 53.3% of patients (54.8% in HICs; 46.6% in LMICs) continued their professional help‐seeking after not being helped by a second professional; 34.8% (36.1% in HICs; 28.6% in LMICs) after a fourth, and 25.2% (27.3% in HICs; 15.2% in LMICs) after a sixth.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of patients who would be expected to persist in professional help‐seeking after previous treatments were not helpful pooled across all diagnostic categories

Whereas Figure 1 estimated that 90.6% of patients would be helped if they persisted in help‐seeking with up to eight professionals, the results in Figure 2 estimate that only 22.8% (25.5% in HICs; 10.9% in LMICs) of patients would persist that long in their help‐seeking.

Predictors of treatment helpfulness

We examined predictors of ever receiving helpful treatment pooled across all diagnostic categories and all professionals seen (Table 5). Significant variation in RRs was found across diagnostic categories (X 2 7=60.7, p<0.001), with higher than average (across categories) RR for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia (1.16‐1.19) and lower than average RR for specific phobia and alcohol use disorder (0.88‐0.68).

Table 5.

Significant predictors of patient‐level treatment helpfulness decomposed through associations with the helpfulness of individual professionals and persistence in help‐seeking pooled across diagnostic categories and number of professionals seen

| Patient‐level treatment helpfulness | Helpfulness of individual professionals | Persistence in help‐seeking after prior unhelpful treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | RR | 95% CI | % | SE | RR | 95% CI | % | SE | RR | 95% CI | |

| Focal diagnostic category | ||||||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 28.3 | 0.6 | 1.19* | 1.12‐1.26 | 26.6 | 0.8 | 1.11* | 1.02‐1.21 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 1.08* | 1.04‐1.11 |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||||||||

| Major depressive episode | 3.1 | 0.2 | 0.94 | 0.75‐1.17 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 0.62‐1.16 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 1.06 | 0.97‐1.16 |

| Mania/hypomania | 6.1 | 0.3 | 1.11 | 0.98‐1.27 | 6.4 | 0.4 | 1.08 | 0.91‐1.29 | 6.4 | 0.4 | 1.03 | 0.95‐1.12 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 19.0 | 0.4 | 1.19* | 1.12‐1.27 | 20.0 | 0.6 | 1.11* | 1.01‐1.21 | 19.4 | 0.7 | 1.07* | 1.04‐1.10 |

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder | 6.0 | 0.3 | 0.99 | 0.83‐1.17 | 5.6 | 0.3 | 1.14 | 0.89‐1.46 | 5.7 | 0.3 | 0.93 | 0.84‐1.02 |

| Specific phobia | 12.8 | 0.4 | 0.88* | 0.77‐0.99 | 12.0 | 0.8 | 0.86* | 0.73‐1.00 | 12.8 | 1.1 | 1.01 | 0.94‐1.08 |

| Social phobia | 13.4 | 0.4 | 1.16* | 1.08‐1.24 | 14.2 | 0.6 | 1.11* | 1.01‐1.22 | 14.2 | 0.7 | 1.05* | 1.01‐1.08 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 11.4 | 0.5 | 0.68* | 0.58‐0.79 | 11.4 | 0.7 | 0.81* | 0.67‐0.98 | 12.6 | 0.9 | 0.81* | 0.75‐0.87 |

| X 2 7 | 60.7* | 18.6* | 54.4* | |||||||||

| Socio‐demographics | ||||||||||||

| Mean age at starting treatment | 33.2 | 0.2 | 1.03* | 1.01‐1.06 | 31.9 | 0.3 | 1.09* | 1.06‐1.12 | 31.3 | 0.4 | 0.99 | 0.98‐1.01 |

| X 2 1 | 6.9* | 30.9* | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Level among non‐students | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.02* | 1.00‐1.05 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.05* | 1.02‐1.08 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 |

| Student status | 12.7 | 0.5 | 0.97 | 0.87‐1.07 | 14.6 | 1.1 | 0.94 | 0.82‐1.08 | 16.1 | 1.3 | 1.00 | 0.95‐1.05 |

| X 2 2 | 11.8* | 25.5* | 0.2 | |||||||||

| Prior history of comorbid disorders | ||||||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 12.8 | 0.5 | 0.93* | 0.87‐0.99 | 14.7 | 0.9 | 0.91* | 0.84‐1.00 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 0.97 | 0.94‐1.00 |

| Substance abuse without dependence | 5.5 | 0.4 | 1.11* | 1.02‐1.20 | 6.7 | 0.9 | 1.05 | 0.93‐1.18 | 7.1 | 1.1 | 1.04* | 1.00‐1.08 |

| X 2 10 | 20.1* | 27.2* | 14.4 | |||||||||

| Treatment type | ||||||||||||

| Mental health specialty sector + medication | 51.0 | 0.9 | 1.20* | 1.12‐1.27 | 61.1 | 1.2 | 0.88* | 0.81‐0.95 | 62.0 | 1.4 | 1.19* | 1.15‐1.23 |

| Complementary/alternative medicine | 19.0 | 0.7 | 1.08* | 1.03‐1.14 | 25.7 | 1.2 | 0.88* | 0.82‐0.94 | 27.4 | 1.4 | 1.06* | 1.04‐1.08 |

| Multiple | 59.8 | 0.8 | 1.11* | 1.03‐1.20 | 70.0 | 1.0 | 1.04 | 0.94‐1.16 | 71.4 | 1.3 | 1.18* | 1.12‐1.24 |

| X 2 5 | 194.0* | 85.5* | 481.1* | |||||||||

| Treatment timing | ||||||||||||

| Treatment delay | 9.6 | 0.2 | 0.96* | 0.94‐0.98 | 9.0 | 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.95‐1.01 | 9.1 | 0.3 | 0.97* | 0.96‐0.98 |

| X 2 1 | 14.0* | 1.6 | 19.7* | |||||||||

significant at the 0.05 level, SE – standard error, RR – adjusted risk ratio, CI – confidence interval

In addition, RR of patient‐reported treatment helpfulness was significantly and positively associated with age at first treatment, high education, prior history of substance abuse without dependence, and treatment occurring either in the mental health specialty sector with medication, in the complementary/alternative medicine sector, or in multiple sectors. RR was significantly and negatively associated with prior history of generalized anxiety disorder and treatment delay.

Decomposition focused on significant patient‐level predictors. The higher‐than‐average RRs for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia were all due to a combination of significantly increased RRs of both individual professionals being helpful (RR=1.11‐1.11) and persisting in help‐seeking (RR=1.05‐1.08). The lower‐than‐average RR for specific phobia and alcohol use disorder were due to significantly reduced RRs of individual professionals being helpful for both disorders (RR=0.86‐0.81) in conjunction with reduced RR of persisting in help‐seeking for alcohol use disorder (RR=0.81).

The increased RRs associated with age at first treatment and high education were both due to associations with helpfulness of individual professionals (RR=1.09‐1.05) rather than with persistence in help‐seeking after earlier treatments were not helpful. The increased RR associated with prior history of substance abuse without dependence, instead, was due to significantly increased persistence in help‐seeking (RR=1.04) and non‐significant increased helpfulness of individual professionals (RR=1.05).

The increased RRs associated with treatment occurring in the mental health specialty sector with medication, in the complementary/alternative medicine sector, and in multiple sectors were more complex, as all involved significantly increased persistence in help‐seeking (RR=1.19‐1.06), but none involved significantly increased helpfulness of individual professionals. In fact, helpfulness of individual professionals was significantly reduced for two of these treatments (RR=0.88‐0.88). The reduced RRs associated with treatment delay and prior generalized anxiety disorder, finally, were due to consistently decreased component associations with both helpfulness of individual professionals (RR=0.98‐0.91) and persistence in help‐seeking (RR=0.97‐0.97), although the RR of treatment delay with persistence in help‐seeking and individual professionals being helpful for prior generalized anxiety disorder were the only statistically significant components.

Variation in predictors across diagnostic categories

We next examined variation in predictors of patient‐level treatment helpfulness across focal diagnostic categories. Two predictors had significantly different RRs predicting treatment helpfulness for alcohol use disorder versus the other diagnostic categories (gender and treatment type) (see Table 6). Four other predictors had significantly different RRs predicting treatment helpfulness within the remaining categories (education, treatment delay, starting treatment after 2000, and childhood adversities) (see Table 7).

Table 6.

Significant predictors of variation in patient‐level treatment helpfulness between patients receiving treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared to other diagnostic categories decomposed through associations with the helpfulness of individual professionals and persistence in help‐seeking pooled across number of professionals seen

| Patient‐level treatment helpfulness | Helpfulness of individual professionals | Persistence in help‐seeking after prior unhelpful treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Gender (female) | ||||||

| AUD | 0.78* | 0.64‐0.96 | 0.77* | 0.61‐0.97 | 0.98 | 0.91‐1.06 |

| Others | 1.05* | 1.00‐1.10 | 1.07* | 1.00‐1.14 | 1.02 | 0.99‐1.04 |

| Treatment type (psychotherapy) | ||||||

| AUD | 1.44* | 1.14‐1.82 | 1.09 | 0.82‐1.45 | 1.20* | 1.07‐1.36 |

| Others | 1.01 | 0.95‐1.07 | 0.92* | 0.84‐1.00 | 1.04 | 1.00‐1.07 |

significant at the 0.05 level, RR – adjusted risk ratio, CI – confidence interval

Table 7.

Significant predictors of patient‐level variation in treatment helpfulness across diagnostic categories other than alcohol use disorder decomposed through associations with the helpfulness of individual professionals and persistence in help‐seeking pooled across number of professionals seen

| Treatment helpfulness at the patient level | Helpfulness of individual professionals | Persistence in help‐seeking after prior unhelpful treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Student status | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 1.21* | 1.07‐1.37 | 1.14 | 0.94‐1.40 | 1.07 | 1.00‐1.14 |

| Specific phobia | 0.73* | 0.57‐0.93 | 0.63* | 0.47‐0.84 | 1.08 | 0.98‐1.19 |

| Treatment delay | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 0.93* | 0.89‐0.97 | 0.96 | 0.90‐1.01 | 0.96* | 0.93‐0.99 |

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder | 0.86* | 0.78‐0.94 | 0.89* | 0.80‐0.99 | 0.95* | 0.91‐0.99 |

| Started treatment after 2000 | ||||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder | 0.76* | 0.66‐0.89 | 0.89 | 0.72‐1.10 | 0.87* | 0.80‐0.95 |

| Childhood adversities | ||||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder, MFF | 0.73* | 0.60‐0.88 | 0.67* | 0.52‐0.86 | 0.91 | 0.83‐1.01 |

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder, other | 0.57* | 0.42‐0.76 | 0.64* | 0.46‐0.89 | 0.78* | 0.66‐0.92 |

significant at the 0.05 level, RR – adjusted risk ratio, CI – confidence interval

Maladaptive family functioning childhood adversities (MFF) included physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, parent mental disorder, parent substance use disorder, parent criminal behavior, and family violence. Other childhood adversities included parent death, parent divorce, other loss of a parent, physical illness, and family economic adversity.

The significant gender difference (X 2 1=7.8, p=0.005) in patient‐level treatment helpfulness for alcohol use disorder compared to the other categories occurred because women treated for the former condition were significantly less likely than men to report that treatment was helpful (RR=0.78), whereas women treated for other diagnostic categories were significantly more likely than men to report that treatment was helpful (RR=1.05) (Table 6). Decomposition showed that the interaction was due to gender differences in the helpfulness of individual professionals rather than to differences in persistence in help‐seeking.

The significantly higher RR of patient‐level treatment helpfulness of psychotherapy than other treatment types for alcohol use disorder was not due to a higher RR of helpfulness at the level of the individual professional, but rather to a higher probability of persistence after earlier unhelpful treatments (RR=1.20).

The significant effect of education in predicting variation in treatment helpfulness across the other diagnostic categories was due to patients who were students at the time of starting treatment differing from other patients (X 2 6=30.7, p<0.001) rather than to an association involving level of educational attainment among non‐students (X 2 6=8.7, p=0.19). Students were significantly more likely than other patients to receive helpful treatment for major depressive disorder (RR=1.21), due to elevated but non‐significant associations of being a student with individual professionals being helpful as well as with persistence in help‐seeking (Table 7). Students were significantly less likely than other patients, instead, to be helped by treatment for specific phobia (RR=0.73). This was true because individual professionals were less likely to be helpful in treating students than other patients with this disorder (RR=0.63). Students did not differ from other patients in patient‐level RR of treatment helpfulness for any of the other diagnostic categories (X 2 1=0.2‐3.4, p=0.66 to 0.06).

We reported above (Table 5) that treatment delay predicted reduced patient‐level treatment helpfulness overall, and that this occurred because patients who were delayed in getting treatment were less likely than other patients to persist in help‐seeking. However, this association was significant only for major depressive disorder and PTSD (RR=0.93‐0.86), in both cases due to reduced persistence in help‐seeking (RR=0.96‐0.95) and for PTSD also reduced helpfulness of individual professionals (RR=0.89). Initial treatment delay did not predict reduced RR of patient‐level treatment helpfulness for any other diagnostic category (X 2 1=0.0‐2.1, p=0.88 to 0.15).

The significant variation in helpfulness by whether treatment started after the year 2000 was due exclusively to an association among patients in treatment for PTSD (RR=0.76), with non‐significantly reduced RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness (RR=0.89) and significantly reduced RR of persistence in help‐seeking (RR=0.87). There was no significant association between year of treatment starting and patient‐level helpfulness for any other diagnostic categories (X 2 1=0.0‐1.8, p=0.92 to 0.18).

The significant variation in helpfulness depending on childhood adversities (X 2 12=31.8, p=0.002) was due to variation associated with both maladaptive family functioning adversities (X 2 6=15.4, p=0.018) and other adversities (X 2 6=22.1, p=0.001), in both cases with childhood adversities predicting reduced RR of helpful treatment only for PTSD (RR=0.73‐0.57). There was no significant association between childhood adversities and patient‐level treatment helpfulness in other diagnostic categories (X 2 1=0.0‐3.5, p=0.91 to 0.06).

DISCUSSION

The lifetime prevalence of disorders across diagnostic categories was 1.2 to 11.5%, consistently higher in HICs than LMICs. About one‐fourth of these disorders received some type of treatment (23.0%), but this rate was approximately two times as high in HICs as LMICs (27.1% vs. 13.8%). Bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were most likely to be treated, and alcohol use disorder least likely. These statistics convey that both prevalence of disorder and receipt of treatment are higher in HICs than LMICs, and that there is considerable variation across diagnoses in probability of receipt of treatment.

A central goal of the study was to evaluate respondent ratings of treatment helpfulness. Overall, 61.7% rated treatment as being helpful, with only a slightly higher percentage among HICs than LMICs (62.6% vs. 57.6%). Treatment was most likely to be rated helpful for generalized anxiety disorder (70.0%) and least likely for alcohol use disorder (44.5%). There were for the most part no differences between HICs and LMICs in the proportion of patients with specific disorders who reported treatment as helpful. The one exception was major depressive disorder, where a higher proportion of patients in HICs than LMICs reported that treatment was helpful (70.1% vs. 62.4%).

A second goal of the study was to evaluate the number of professionals that patients needed to see before receiving a treatment that they considered to be helpful. We found that only about half the patients who reported receiving helpful treatment were helped by the first professional they saw (26.1% helped by the first professional seen vs. 61.7% helped overall). In other words, seeking help from two or more professionals was the norm among patients who received helpful treatment. Cumulative probability of receiving helpful treatment nearly doubled to 51.2% among individuals who sought treatment from a second professional. Less dramatic increments occurred after seeing additional professionals, with a projected cumulative probability of receiving helpful treatment of 90.6% after the eighth professional seen. There were few significant differences between HICs and LMICs in this regard.

A third goal of the study was to evaluate persistence in professional help‐seeking among patients whose earlier treatments were not helpful. Across all diagnostic categories, 70.7% of patients reported persisting in help‐seeking by seeing a second professional if the first professional was not helpful, with conditional probabilities of persistence continuing to be high (in the range 66.7‐100% up through 20 professionals seen) after earlier unhelpful treatments. These conditional probabilities were somewhat higher in HICs than LIMCs. Despite the high conditional probabilities, though, cumulative probabilities of persistence decreased markedly over successive professionals, with only 22.8% of patients overall (25.5% in HICs; 10.9% in LMICs) expected to persist in seeking treatment from up to eight professionals, the number needed for more than 90% of patients to receive helpful treatment.

We also looked at predictors of helpfulness at the patient‐disorder level and then disaggregated the significant predictors into the separate associations with helpfulness of individual professionals and persistence in help‐seeking after earlier treatments that were not helpful. We found that the variation across diagnostic categories in probability of treatment being helpful was driven by five disorders: three of them with higher‐than‐average RR of treatment helpfulness (major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia) and two with lower‐than‐average RR of treatment helpfulness (specific phobia, alcohol use disorder). In almost all these cases, the significant patient‐level association was due to significantly increased persistence in help‐seeking rather than significantly increased helpfulness of individual professionals. Why it should be that treatments differ in helpfulness in these ways across disorders remains to be clarified.

Net of these differences across diagnostic categories, we found a complex series of significant associations between diverse predictors and RR of patient‐level treatment helpfulness. We began by examining these predictors pooled across all diagnostic categories and then we disaggregated the predictors by these categories. The most stable predictors were those significant at the aggregate level that did not vary in importance across focal diagnostic categories. There were five such stable predictors: age at first treatment, educational attainment among non‐students, two prior lifetime comorbid disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, substance abuse without dependence), and treatment type.

The first two of these five – age at first treatment and level of educational attainment among non‐students – were associated with significantly increased RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness, but were unrelated to persistence in help‐seeking. A plausible possibility is that increasing age and education are both indicators of maturity and cognitive complexity, both of which might reasonably be expected to promote treatment success across diagnostic categories.

The third stable predictor, prior comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, predicted reduced RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness, but was unrelated to persistence in help‐seeking. This is an intriguing result, as a considerable amount of research has shown that comorbid generalized anxiety disorder predicts reduced treatment response for major depressive disorder 29 . We are unaware, though, of any research on comorbid generalized anxiety disorder predicting reduced treatment response for other mental disorders. This might be a fruitful avenue of investigation.

The fourth stable predictor, prior comorbid substance abuse without dependence, was associated with increased persistence in help‐seeking across all diagnostic categories. The meaning of this result is not clear, but it is worthy of investigation in future research on patterns and predictors of persistence in help‐seeking.

The final stable predictor, treatment type, was more complex, because it was due to elevated RR of patient‐level treatment helpfulness across several different types of treatment (medication prescribed by a mental health specialist, complementary/alternative medicine, and treatment in multiple sectors), but none of these involved increased RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness. Instead, increased persistence in help‐seeking accounted for the patient‐level associations of these treatment types with treatment helpfulness. In two cases (medication and complementary/alternative medicine), these treatments were associated with significantly reduced RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness, possibly indicating that more severe cases received these types of treatment.

Other predictors varied in importance across diagnostic categories. Two of these were unique to alcohol use disorder. One of them, being male, predicted significantly increased RR of individual professional treatment helpfulness for alcohol use disorder but no other diagnoses. The other, receiving psychotherapy in the absence of any other treatment, predicted increased persistence in help‐seeking for alcohol use disorder but not for any other diagnostic categories. The explanations for these specifications are unclear, but plausible speculations can be made. For example, it might be that the preponderance of males among patients with alcohol use disorder means that some of the most common treatments, some of which are delivered in group formats, are more effective for men than women. The selection of psychotherapy as the only treatment modality may indicate a more serious engagement with the treatment process for patients with alcohol use disorder, thereby predicting increased RR of persistence in help‐seeking.

Three other noteworthy predictors that varied in importance across disorders other than alcohol use disorder were student status, treatment delay, and childhood adversities. Students were more likely than other patients to be helped when treated for major depressive disorder, but less likely to be helped when treated for specific phobia. It is unclear why these differences occurred, but it is plausible that they involve differential effects of timely treatment, which in the case of major depressive disorder might be related to good treatment response, while in the case of specific phobia might be a severity marker given the comparatively low treatment rate of this condition. WMH data are limited in their ability to explore these hypotheses, because the retrospective evaluations make it impossible to assess disorder severity at the time of starting treatment. However, these findings could be the starting point for prospective studies in more focused disorder‐specific patient samples.

Both types of childhood adversities considered here were found to be associated with significantly reduced RR of patient‐level helpfulness, but only for PTSD and largely because of reduced RR of individual professionals being helpful. This might reflect a special difficulty in treating PTSD associated with childhood traumas, a possibility consistent with the rationale underlying the inclusion of a special diagnostic category for complex PTSD in the ICD‐11 diagnostic system 30 , 31 .

These results provide useful information on several fronts. First, it is important to note that about one‐fourth of patients were helped by the first professional they saw, that the cumulative probability of being helped almost doubled after seeing a second professional, and that persistence in help‐seeking paid off, with more than 90% of patients being helped after seeing up to eight professionals. Yet fewer than one‐fourth of patients persisted that long in their help‐seeking. The implication is clear that a research priority should be to increase understanding of the determinants of persistence in help‐seeking.

Second, similarities and differences between HICs and LMICs are instructive. Across each of the diagnoses, lifetime disorder prevalence was higher in HICs than LMICs, and for each disorder the proportion of individuals who received treatment was nearly double in HICs compared to LMICs. However, once treatment occurred, few differences were found between HICs and LMICs in patient‐reported treatment helpfulness. This meant that persistence was needed equally in LMICs and HICs to be sure of receiving helpful treatment. Yet persistence in help‐seeking was significantly lower in LMICs than HICs. This means that the greater proportional burden of unmet need for treatment in LMICs than HICs is due to a combination of lower entry into treatment and lower persistence. Many of the barriers that create these differences are structural ones, not investigated here 32 .

Third, we found numerous significant predictors of patient‐level treatment helpfulness, some of them consistent across disorders but most varying in importance across disorders. Disaggregation found that some of these variables were important because they predicted differential response to treatment, while others were important because they predicted differential persistence in help‐seeking after earlier unhelpful treatments.

The first of these two disaggregated components is related to the burgeoning research area of precision psychiatry 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . Our results may add information to models aimed to guide the matching of patients to the treatment that is likely to be of most value to them. The second component is somewhat neglected, but of equal importance, since helpful treatment typically requires persistence in help‐seeking. Some epidemiological research has been carried out on treatment dropout 40 and interventions have been developed to reduce it 41 , 42 . There is some emerging research showing that case management can be useful in encouraging continuation of help‐seeking with new professionals when earlier treatments are not helpful 43 . But we are aware of no comparable research designed to investigate barriers and interventions to increase persistence in help‐seeking among patients with common mental disorders. Our results suggest that this type of work could be of great value.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, we had limited information about the exact nature of the interventions that respondents received. Information was also lacking on quality of treatment delivery and adherence on the part of patients. These factors made it impossible to compare the effectiveness of different interventions or types of professionals. Because of this, it would be a mistake to interpret our results regarding the associations of treatment types with patient‐reported helpfulness as evidence that these types do not differ in quality. Indeed, we know that the type and quality of training of the professional makes a difference and that the WMH design obscures this variation because of not being based on experimental assignment 44 .

Second, respondent evaluations of treatment helpfulness were based on unspecified criteria. Even though the patient perspective on treatment quality is becoming a focus of increasing interest, not least of all because it is a strong predictor of treatment adherence 8 , more information is needed about the basis of these evaluations to move beyond the basic level of analysis presented here. In addition, treatment helpfulness needs to be thought of as being graded rather than a dichotomy and as changing over time as patient needs change.

Third, interactions were examined one at a time, rather than together, to avoid problems with model instability. Further analyses beyond those reported here are needed to investigate joint associations of multiple significant interactions, but preferably based on a more disaggregated analysis than we were able to carry out here. In the ideal case, these future analyses should be conducted with long‐term prospective data in clinical samples rather than with the retrospective data used in this study, but following patients over much longer periods of time than in typical clinical studies.

Despite these limitations, this study provides unique, albeit preliminary, information about treatment helpfulness from the patient perspective in real‐world contexts and over a diverse set of diagnostic categories and countries. We find that treatments are perceived as helpful, but that this varies across diagnoses, and that persistence in help‐seeking is typically needed to find helpful treatment. The cumulative probability of success in finding helpful treatment is very high if help‐seeking is persistent, but this persistence is the heretofore neglected key.

It is important to recognize that these results are distinct from, but complement, those in randomized controlled trials. The latter evaluate the impacts of individual treatments. The present study, instead, underscores the fact that initial treatments often are not successful in the real world, but that persistent help‐seeking across the myriad of evidence‐based treatments that exist for common mental disorders has a very high probability of resulting in a positive outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The WMH Survey collaborators are S. Aguilar‐Gaxiola, A. Al‐Hamzawi, J. Alonso, Y.A. Altwaijri, L.H. Andrade, L. Atwoli, C. Benjet, G. Borges, E.J. Bromet, R. Bruffaerts, B. Bunting, J.M. Caldas de Almeida, G. Cardoso, S. Chardoul, S. Chatterji, A. Cia, L. Degenhardt, K. Demyttenaere, S. Florescu, G. de Girolamo, O. Gureje, J.M. Haro, M.G. Harris, H. Hinkov, Chi‐Yi Hu, P. de Jonge, A.N. Karam, E.G. Karam, G. Karam, N. Kawakami, R.C. Kessler, A. Kiejna, V. Kovess‐Masfety, S. Lee, J.‐P. Lepine, J.J. McGrath, M.E. Medina‐Mora, J. Moskalewicz, F. Navarro‐Mateu, M. Piazza, J. Posada‐Villa, K.M. Scott, T. Slade, J.C. Stagnaro, D.J. Stein, M. ten Have, Y. Torres, M.C. Viana, D.V. Vigo, H. Whiteford, D.R. Williams and B. Wojtyniak. The WMH Survey Initiative has been supported by the US Public Health Service (grant nos. R01 MH070884, R13‐MH066849, R01‐MH069864, R01 DA016558, R03‐TW006481), the MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho‐McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the WHO, other sponsoring organizations, agencies or governments. The authors are grateful to the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. R.C. Kessler and A.E. Kazdin are joint first authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dattani S, Ritchie H, Roser M. Mental health. https://ourworldindata.org/mental‐health. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis 1980‐2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldstein BI, Baune BT, Bond DJ et al. Call to action regarding the vascular‐bipolar link: a report from the Vascular Task Force of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders. Bipolar Disord 2020;22:440‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P, Albor Y et al. Sources of stress and their associations with mental disorders among college students: results of the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Initiative. Front Psychol 2020;11:1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang YH, Li JQ, Shi JF et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry 2020;25:1487‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P et al. Scaling‐up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:415‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christensen MK, Lim CCW, Saha S et al. The cost of mental disorders: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020;29:e161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins A, Safran DG, Fiore N et al. Pathway to patient‐centered measurement for accountability. https://www.healthaffairs.org. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruffaerts R, Harris MG, Kazdin AE et al. Perceived helpfulness of treatment for social anxiety disorder: findings from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2022; doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Vries YA, Harris MG, Vigo D et al. Perceived helpfulness of treatment for specific phobia: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. J Affect Disord 2021;288:199‐209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Degenhardt L, Bharat C, Chiu WT et al. Perceived helpfulness of treatment for alcohol use disorders: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;229:109158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris MG, Kazdin AE, Chiu WT et al. Findings from World Mental Health Surveys of the perceived helpfulness of treatment for patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:830‐41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nierenberg AA, Harris MG, Kazdin AE et al. Perceived helpfulness of bipolar disorder treatment: findings from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Bipolar Disord 2021;23:565‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stein DJ, Harris MG, Vigo DV et al. Perceived helpfulness of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Depress Anxiety 2020;37:972‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stein DJ, Kazdin AE, Ruscio AM et al. Perceived helpfulness of treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a World Mental Health Surveys report. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scott KM, de Jonge P, Stein DJ et al (eds). Mental disorders around the world: facts and figures from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93‐121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pennell B‐E, Mneimneh Z, Bowers A et al. Implementation of the World Mental Health Surveys. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds). The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008:33‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harkness J, Pennell B‐E, Villar A et al. Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. In: Kessler R, Üstün T (eds). The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008:91‐113. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O et al. Clinical calibration of DSM‐IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:122‐39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non‐patient Edition (SCID‐I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Knäuper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N et al. Improving accuracy of major depression age‐of‐onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1999;8:39‐48. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:378‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heeringa SG, Wells JE, Hubbard F et al. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler R, Üstün T (eds). The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008:14‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Halli SS, Rao KV. Advanced techniques of population analysis. Boston: Springer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Institute SAS Inc. SAS /STAT® 14.3 Software Version 9.4 for Unix. Cary: SAS Institute Inc., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kessler RC. The potential of predictive analytics to provide clinical decision support in depression treatment planning. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2018;31:32‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. First MB, Gaebel W, Maj M et al. An organization‐ and category‐level comparison of diagnostic requirements for mental disorders in ICD‐11 and DSM‐5. World Psychiatry 2021;20:34‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nestgaard Rød Å, Schmidt C. Complex PTSD: what is the clinical utility of the diagnosis? Eur J Psychotraumatol 2021;12:2002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarikhani Y, Bastani P, Rafiee M et al. Key barriers to the provision and utilization of mental health services in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a scope study. Community Ment Health J 2021;57:836‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Acion L, Kelmansky D, van der Laan M et al. Use of a machine learning framework to predict substance use disorder treatment success. PLoS One 2017;12:e0175383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fernandes BS, Williams LM, Steiner J et al. The new field of ‘precision psychiatry’. BMC Med 2017;15:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chekroud AM, Bondar J, Delgadillo J et al. The promise of machine learning in predicting treatment outcomes in psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2021;20:154‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kessler RC, Luedtke A. Pragmatic precision psychiatry – a new direction for optimizing treatment selection. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1384‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maj M, Stein DJ, Parker G et al. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with depression aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry 2020;19:26‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maj M, van Os J, De Hert M et al. The clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry 2021;20:4‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stein DJ, Craske MG, Rothbaum BO et al. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with an anxiety or related disorder aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry 2021;20:336‐56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wells JE, Browne MO, Aguilar‐Gaxiola S et al. Drop out from out‐patient mental healthcare in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey initiative. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:42‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician‐patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pérez‐Jover V, Sala‐González M, Guilabert M et al. Mobile apps for increasing treatment adherence: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dieterich M, Irving CB, Bergman H et al. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maj M. Helpful treatment of depression – delivering the right messages. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:784‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]