Abstract

Hexokinase domain containing protein-1, or HKDC1, is a widely expressed hexokinase that is genetically associated with elevated 2-hour gestational blood glucose levels during an oral glucose tolerance test, suggesting a role for HKDC1 in postprandial glucose regulation during pregnancy. Our earlier studies utilizing mice containing global HKDC1 knockdown, as well as hepatic HKDC1 overexpression and knockout, indicated that HKDC1 is important for whole-body glucose homeostasis in aging and pregnancy, through modulation of glucose tolerance, peripheral tissue glucose utilization, and hepatic energy storage. However, our knowledge of the precise role(s) of HKDC1 in regulating postprandial glucose homeostasis under normal and diabetic conditions is lacking. Since the intestine is the main entry portal for dietary glucose, here we have developed an intestine-specific HKDC1 knockout mouse model, HKDC1Int–/–, to determine the in vivo role of intestinal HKDC1 in regulating glucose homeostasis. While no overt glycemic phenotype was observed, aged HKDC1Int–/– mice fed a high-fat diet exhibited an increased glucose excursion following an oral glucose load compared with mice expressing intestinal HKDC1. This finding resulted from glucose entry via the intestinal epithelium and is not due to differences in insulin levels, enterocyte glucose utilization, or reduction in peripheral skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Assessment of intestinal glucose transporters in high-fat diet–fed HKDC1Int–/– mice suggested increased apical GLUT2 expression in the fasting state. Taken together, our results indicate that intestinal HKDC1 contributes to the modulation of postprandial dietary glucose transport across the intestinal epithelium under conditions of enhanced metabolic stress, such as high-fat diet.

Keywords: diabetes, postprandial hyperglycemia, HKDC1, glucose absorption, glucose homeostasis

The severity and frequency of postprandial hyperglycemic excursions affects glycemic control of individuals with or without diabetes (1-4). Postprandial hyperglycemia (PPH) contributes to overall glycemic variability, which has emerged as an independent risk factor for total mortality and death due to cardiovascular disease in patients with both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes (5-7). More specifically, PPH is linked to increased cellular oxidative stress, disordered endothelial function, reduction in plaque stability, impaired myocardial perfusion, and development of coronary artery disease (8-14). Also of significance is the need to control postprandial glucose excursions during pregnancy to prevent adverse maternal and fetal outcomes (15-17). Currently, there are only a few medications designed to prevent intestinal glucose uptake, and their usage is limited due to gastrointestinal side effects (18-20). Thus, targeting PPH to enhance glucose control by inhibiting the initial entry of dietary glucose requires greater understanding of the mechanisms promoting glucose absorption.

Hexokinase domain containing protein-1 (HKDC1) is a novel fifth hexokinase (HK) containing 70% sequences homology to HK1, glucose and ATP bindings sites that are conserved among the HKs, and HK activity (21-23). HKDC1 is expressed in many human and mouse tissues, including high expression within the intestinal epithelium (23, 24). Early studies in human populations suggested a link between HKDC1 and postprandial glycemic control in pregnancy. Data from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) Study identified genetic variants of the HKDC1 locus that are associated with maternal elevated 2-hour glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). This is hypothesized to be through modulation of regulatory elements that control HKDC1 expression, such that lower HKDC1 expression corresponded to women with higher 2-hour post-OGTT glucose levels (22, 25-27). These cohort analyses detailed the first link between HKDC1, postprandial glucose levels, and the development of gestational diabetes, and suggested a physiological role for HKDC1 in human glucose homeostasis.

Using mouse models differentially expressing HKDC1, our laboratory provided initial insights into the biochemical roles of HKDC1 in glucose homeostasis. We first created a transgenic mouse in which HKDC1 is globally reduced and assessed the effects of a glucose load on blood glucose levels (23). We found that reduced HKDC1 expression in 28-week-old mice or at day 15 of pregnancy demonstrated increased glucose excursions following an oral or intraperitoneal glucose load, along with reduced peripheral tissue uptake of glucose and reduced hepatic energy storage, suggesting HKDC1 is needed to maintain glucose homeostasis under conditions of higher metabolic stress. We also found that hepatic overexpression of HKDC1 in pregnant mice improved glucose tolerance along with hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity during an intraperitoneal glucose load, while the opposite occurred when hepatic HKDC1 was knocked out (28).

Considering the contribution of PPH to glycemic variability and cardiovascular complications in diabetes, coupled with our findings that HKDC1 has roles in modulating whole-body glucose utilization and has high expression in the intestine, here we sought to characterize the function of intestine-specific HKDC1 on dietary glucose uptake in the presence of an obesogenic challenge. We created a transgenic mouse specifically lacking intestinal HKDC1 and studied the resultant effects on glucose metabolism when fed a normal chow (NC) or a high-fat diet (HFD). Our data indicate a role for intestine-specific HKDC1 on dietary glucose absorption under normal and diabetic conditions.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J mice expressing Cre recombinase under the direction of the mouse villin 1 promoter (Villin-cre mice) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (JAX stock #004586) (29). Expression of Cre recombinase in these mice is limited to villus and crypt epithelial cells of the intestine in a pattern resembling Vil1 expression. C57BL/6J HKDC1fl/fl mice were generated by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and obtained from the Knockout Mouse Project Repository (www.komp.org). Mice were housed at the Biological Resources Laboratory of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) under a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle with ad libitum access to chow diet (Envigo #7012, Madison, WI, USA), unless otherwise noted. All mouse studies were approved by the UIC Animal Care and use Committee and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at UIC. Male mice were utilized in experiments.

Creation of Intestine-specific HKDC1 Knockout Transgenic Mice

Villin-cre transgenic mice were mated with HKDC1fl/fl mice to create mice with the HKDC1 gene knocked out in Vil1-expressing intestinal tissue (HKDC1Int–/– mice). The presence of floxed HKDC1 and Villin-Cre were assessed through genotyping using REDTaq ReadyMix PCR reaction mix (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) with the primers listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genotyping primers for HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice

| Genotype | Primer sequences (5′→3′) | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|

| HKDC1-floxed | F: GAGATGGCGCAACGCAATTAATG R: AGCTAAGTCCAAGCCCACAAACTCC |

322 bp |

| Villin-Crea | F: CATGTCCATCAGGTTCTTGC R: TTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGTCCA |

195 bp |

| Internal positive control | F: CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT R: GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC |

324 bp |

a Band corresponding to Villin-Cre transgene will only appear in HKDC1Int–/– mice.

Mouse Diets

All mice were maintained on a chow diet (Envigo #7012) until 6 weeks of age. At 6 weeks, cohorts were continued on this diet or switched to a HFD (Envigo #TD.06414). The assigned diet at week 6 was continued until final analyses at week 28.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from 20-mg intestinal sections using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and chloroform for phase separation. RNA was purified using RNEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and resuspended in DNase-/RNase-free water (Qiagen). A 1-µg bolus of purified RNA per sample was reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and quantified via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) with 0.625 µM primer concentrations for each reaction. The primers utilized for qPCR are in Table 2. Data were collected and analyzed using the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and CFX Maestro 2.2 software (Bio-Rad), respectively.

Table 2.

Quantitative PCR sequences

| Gene | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| HKDC1 | CGGAGGATCCAAGTTTCGGG | ACGGGTGATTTCATTGGGCA |

| HK1 | TGCCATGCGGCTCTCTGATG | CTTGACGGAGGCCGTTGGGTT |

| HK2 | TTTTGCCAAGCGTCTCCATAAG | GCCGCTGCCATCCTCAGAGCGGA |

| GK | GAGGTCGGCATGATTGTGGGCA | ACACACATGCGCCCCTCATCGCC |

| GAPDHa | GAGGGATGCTGCCCTTACCC | GTCTACGGGACGAGGAAACAC |

Abbreviations: HKDC1, hexokinase domain containing protein-1; HK1, hexokinase 1; HK2, hexokinase 2; GK, glucokinase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

a Housekeeping gene.

Blood Glucose Measurements

Blood glucose was measured at the tail vein using a OneTouch UltraMini glucose monitor (Lifescan Inc, Milpitas, CA, USA).

Serum Insulin Measurements

Blood was collected from the tail vein in heparinized capillary tubes, transferred to nonheparinized Eppendorf tubes, centrifuged at 2000 rpm at 4°C for 20 minutes, and the supernatant containing serum was collected. Serum insulin levels were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (#80-INSMSU-E01, RRID https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:AB_2792981, ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA).

Oral and Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Tests

After a 16-hour overnight fast, mice were administered 2 g/kg body weight of glucose via either oral gavage or intraperitoneal injection, and blood glucose was assessed as described above.

Radiolabeled Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

After an overnight 16-hour fast, mice were challenged with an oral radiolabeled glucose solution containing 2 g/kg body weight of unlabeled glucose combined with 15 µCi 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-O-glucose (2-dOg) (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA, USA). Tail vein blood was obtained every 5 minutes. After 30 minutes, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by cardiac puncture for blood collection. Mouse organs were harvested and snap frozen until processing. Blood glucose and insulin were assayed as described above. For measuring 14C tracer contents, blood samples were placed in EDTA-treated tubes and centrifuged (2000g for 15 minutes). The plasma supernatant was mixed with Ultima Gold liquid scintillation cocktail (Perkin Elmer) and counted using a scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter #LS6500, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Measurement of Intestinal and Muscle 14C Content

One hundred milligrams of intestinal mucosal scrapings and muscle tissue samples were homogenized in water using a polytron, heated to 95°C for 15 minutes, then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 minutes. To measure phosphorylated 14C 2-dOg, 400 μL of supernatant was added to Poly-Prep prefilled chromatography anion exchange columns (Bio-Rad), washed with water, and the bound content was eluted (0.2 M formic acid, 0.5 M ammonium acetate solution) and utilized for scintillation counting.

Insulin Tolerance Test

Mice were fasted for 6 hours, then administered 0.75 units/kg body weight of Humalog insulin (Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA). Blood was collected and assessed for glucose as described earlier.

Sodium Pyruvate Challenge

Mice were fasted overnight for 16 hours, then given 2 mg/g body weight of sodium pyruvate (Sigma). Blood glucose levels were assessed as detailed earlier.

Intestinal Brush Border Preparation

The proximal half of the small intestine was removed and flushed with cold phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) to arrest GLUT2 in the apical membrane. Mucosa was scraped and homogenized with a polytron in 15 mL of homogenization buffer (300 mM mannitol, 5 mM EGTA, 12 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1) supplemented with Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Next, 20 mL of ice-cold water with 20 mM MgCl2 was added to each homogenate and the resultant samples were mixed by inversion (15 minutes at 4°C) for divalent cation precipitation. Samples were then centrifuged at 3000g (15 minutes at 4°C) to separate aggregated membranes, supernatants transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 30 000g (30 minutes at 4°C). Pellets were resuspended in 35 mL of buffer containing 150 mM mannitol, 2.5 mM EGTA, 6 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1. MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 20 mM, and samples were mixed and centrifuged exactly as described above. Pellets containing brush border membrane vesicles (BBMVs) were resuspended in 50 µL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline and used for analyses.

Immunoblotting

Intestinal sections were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), except brush border preparations (see below), supplemented with Halt protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). A 40-µg bolus of each protein sample was added to Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) at a ratio of 1:1, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using Mini-PROTEAN TGX 4% to 15% Gels (Bio-Rad), and transferred to Trans-Blot Turbo Mini-size nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat, dried milk in tris-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at 25°C, then incubated with HKDC1 (#ab228729, RRID https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:AB_2910178, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and β-actin (#A2228, RRID https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:AB_476697, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) antibodies. For BBMVs, 5 µg of each sample was added to Laemmli sample buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Trans-Blot Turbo Mini-size nitrocellulose membranes as detailed above. Membranes were blocked as above, then incubated with SGLT1 (#ab14686, RRID https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:AB_301411, Abcam, Princeton, NJ, USA), GLUT2 (#sc-518022, RRID https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:AB_2890904, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), or β-actin (#A2228, RRID:AB_476697, Sigma Aldrich) antibodies overnight at 4°C. All nitrocellulose membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI) at 25°C for 1 hour. Membranes were washed, incubated with Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK), and the emitted light signal was detected and analyzed using a ChemiDoc MP Imager (Bio-Rad) and Image Lab software, version 6.0 (Bio-Rad), respectively. Densitometric analysis for SGLT1 and GLUT2 was performed using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, and data are presented as means ± SEM. Glucose, insulin, gluconeogenesis, and blood radiolabeled tracer content were analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction. All other data were compared by a 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test to assess for statistical significance.

Results

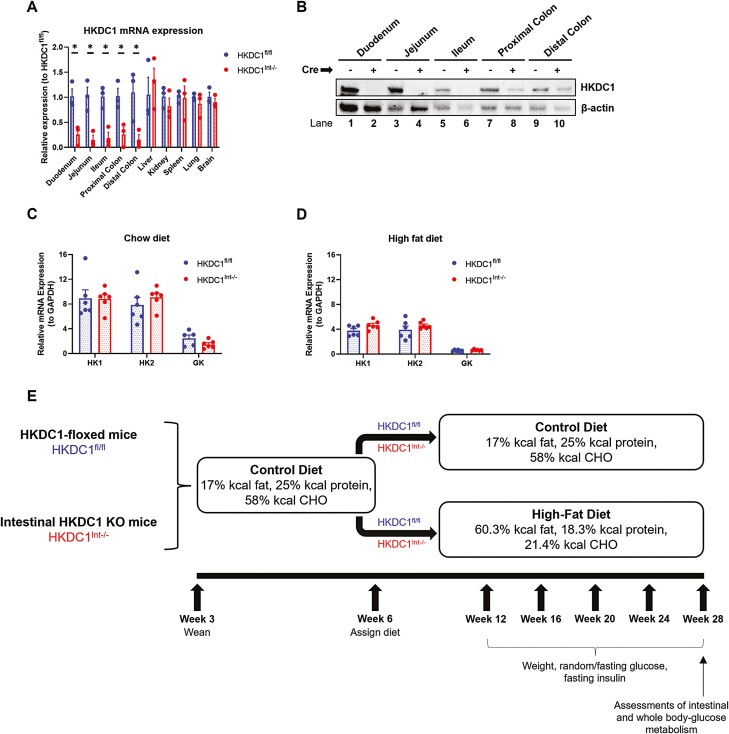

Assessment of Intestinal HKDC1 and Hexokinase Expression in HKDC1Int–/– Mice

HKDC1 mRNA levels were assessed in the small and large intestine (Fig. 1A). For comparison, we also assessed HKDC1 mRNA levels in the liver and in the kidney, spleen, lung, and brain, which have high HKDC1 expression (23, 24). We found that HKDC1Int–/– mice have significantly less HKDC1 mRNA in intestinal tissue samples than HKDC1fl/fl mice, whereas expression in nonintestinal tissues remained comparable. Assessment of HKDC1 protein expression within the intestinal epithelium showed that HKDC1Int–/– mice have reduced HKDC1 protein expression (Fig. 1B), which correlates with intestinal HKDC1 mRNA expression. These results confirm appropriate knockout of HKDC1 within the intestine in HKDC1Int–/– mice. Since HKDC1 is a novel HK, we next determined whether knockout of HKDC1 led to compensatory changes in the abundances of HK1, HK2, and glucokinase (GK) within the intestines of 28-week-old mice maintained on NC (Fig. 1C) or HFD (Fig. 1D). Utilizing purified mRNA from mucosal scrapings of the proximal half of the small intestine, we found that the mRNA abundances of HK1, HK2, and GK were unaffected by intestinal HKDC1 status regardless of diet.

Figure 1.

Assessment of HKDC1 and hexokinase mRNA expression, and experimental design. HKDC1 mRNA expression in various tissues in HKDC1Int–/– mice was assessed by qPCR and compared with expression in HKDC1fl/fl mice (A). HKDC1 protein expression within sections of intestinal epithelium was assessed with immunoblotting (B). To assess whether knockout of intestinal HKDC1 alters the mRNA abundance of other HKs within the intestine, mucosa from the proximal half of the small intestine in 28-week-old chow- and HFD-fed mice was processed, mRNA purified, and qPCR performed to quantify mRNA expression for HK1, HK2, and GK, normalized to GAPDH (C, D). The experimental setup is diagrammed and discussed in the text (E). n = 3-6 for mRNA analyses, *P < .05, Student t test.

After confirming proper HKDC1 knockout in the intestine, we next assessed the role of intestine-specific HKDC1 on glucose metabolism. HKDC1Int–/– and HKDC1-floxed (HKDC1fl/fl) mice initially on an NC diet, for first 6 weeks of life, were separated into groups fed NC or HFD to induce an obesogenic state. These mice were followed to age 28 weeks, which is the age at which studies with global HKDC1 knockdown mice demonstrated a role for HKDC1 in whole-body glucose homeostasis (Fig. 1E) (23, 30, 31). Mice were assessed for weight, fasting blood glucose, fasting serum insulin, and ad libitum blood glucose at multiple time points until final analyses were conducted at age 28 weeks.

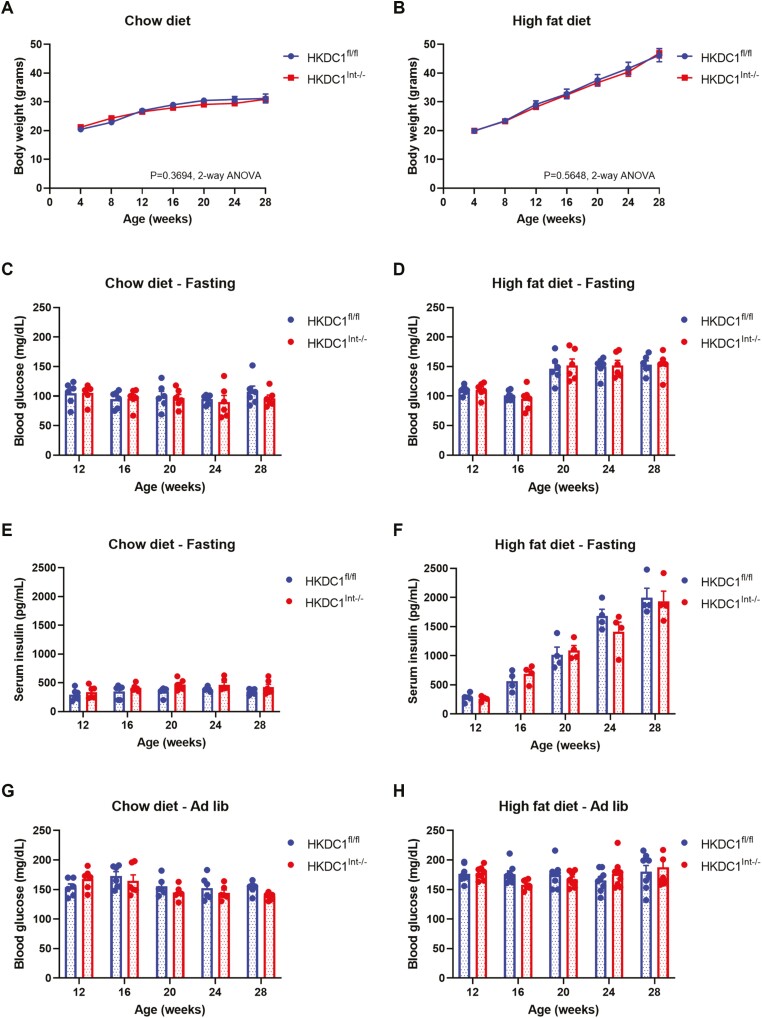

Intestinal HKDC1 Knockout Does not Result in an Overt Glycemic Phenotype

The body weights of HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice were assessed from age 4 to 28 weeks (Fig. 2A and 2B). Mice fed NC (Fig. 2A) or HFD (Fig. 2B) did not show a difference in weight trend based on intestinal HKDC1 status. We next assessed fasting blood glucose (Fig. 2C and 2D) and serum insulin (Fig. 2E and 2F) after an overnight 16-hour fast at 4-week intervals. Fasting blood glucose and serum insulin levels in NC-fed mice (Fig. 2C and 2E) were similar regardless of intestinal HKDC1 status. Mice fed HFD exhibited higher fasting glucose levels (Fig. 2D) and progressively higher fasting insulin levels (Fig. 2F) after about 14 weeks of HFD, which correlates with previous observations of C57Bl/6J mice fed HFD (32, 33); however, there were no identified differences based on intestinal HKDC1 status. Similarly, ad libitum glucose levels in mice fed NC (Fig. 2G) or HFD (Fig. 2H) were not different between HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice. These data demonstrate that HKDC1Int–/– mice do not develop an overt glycemic phenotype, and that overt weight gain, hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in mice chronically fed HFD are due to the diet.

Figure 2.

Knockout of intestinal HKDC1 does not result in an overt glycemic phenotype. Chow-fed (A, C, E, G) and HFD-fed (B, D, F, H), were assessed at multiple time points for weight (A, B), blood glucose (C, D), and serum insulin (E, F) after an overnight 16-hour fast, as well as blood glucose during ad libitum feeding (G, H). All data are reported as the mean ± SEM. Weight changes over time were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA, whereas fasting and ad libitum glucose and fasting insulin data were assessed with Student’s t test, with P < .05 signifying significance.

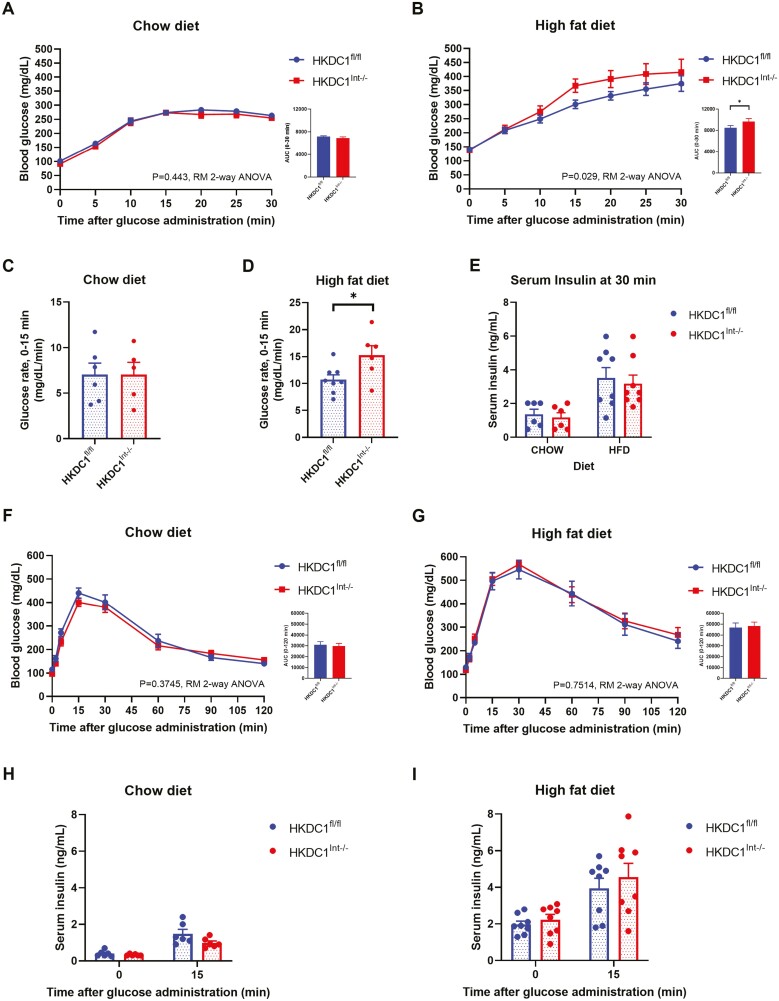

28-Week-Old Mice Lacking Intestinal HKDC1 Fed HFD Exhibit Increased Blood Glucose Excursion After an Oral Glucose Load

We next assessed glucose tolerance by OGTT at age 28 weeks following a 16-hour fast. Following an oral glucose load, the resultant blood glucose excursion within the first 30 minutes was closely assessed, given prior HKDC1 global knockdown mice showed statistically significant differences in blood glucose levels at 15 and 30 minutes into an OGTT in both male and female mice (23). In mice fed NC (Fig. 3A), the overall blood glucose excursion measured did not differ based on intestinal HKDC1 status. In contrast, HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice exhibited a greater glucose excursion following the glucose load compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3B). Assessment of the rate of glucose excursion (Fig. 3C and 3D) between measured time points indicated that in HFD-fed mice, HKDC1Int–/– mice showed a significantly increased rate within the first 15 minutes following the glucose gavage compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3D), which was not seen in mice fed NC (Fig. 3C). The increased glucose excursion rate in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– was not due to overt differences in insulin levels (Fig. 3E). Further, this result was due to introduction of glucose through the intestine, as an intraperitoneal glucose load did not alter blood glucose excursion at any point through 2 hours, nor alter post-load insulin response between aged NC- (Fig. 3F and 3H) or HFD-fed (Fig. 3G and 3I) HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice. Assessment of glucose tolerance during an OGTT in HKDC1Int–/– mice compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice at age 12 weeks did not demonstrate a significant difference in glucose excursion regardless of diet (see supplemental Fig. 1A and B (34)), suggesting a role for intestinal HKDC1 in older mice.

Figure 3.

HKDC1Int–/– mice chronically fed a HFD demonstrate an increased blood glucose excursion following an oral but not intraperitoneal glucose load. After a 16-hour overnight fast, chow-fed (A) and HFD-fed (B) mice were administered a 2 g/kg body weight oral glucose load and blood glucose (mg/dL) responses were assessed. The rate of blood glucose excursion (mg/dL/min) within the first 15 minutes following the glucose load was determined in chow-fed (C) and HFD-fed (D) mice using blood glucose data from 0- and 15-minute time points. Serum insulin (E) levels were analyzed at the end of the OGTT. After a 16-hour overnight fast, chow-fed (F) and HFD-fed (G) mice were administered a 2 g/kg body weight intraperitoneal glucose load and blood glucose (mg/dL) responses were assessed. Serum insulin levels during the Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) were analyzed after the overnight fast and 15 minutes after the glucose load in Chow- (H) and HFD-fed (I) mice. n = 5-6 for chow-fed mice, n = 6-8 for HFD-fed mice. All data are reported as the mean ± SEM. *P < .05, Student’s t test, for glucose rates and serum insulin analysis, as well as area under the curve; OGTT and IPGTT data are analyzed by repeated measures (RM) 2-way ANOVA.

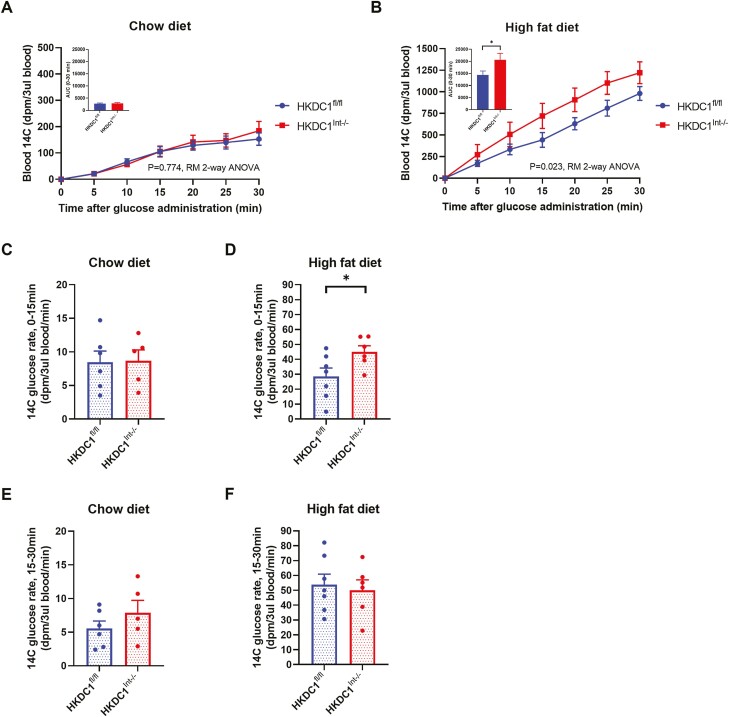

The regulation of blood glucose is orchestrated by processes involving multiple organs simultaneously (35, 36). Therefore, to specifically assess the contribution of intestinal HKDC1 to glucose homeostasis, we conducted OGTTs supplemented with 14C 2-dOg, which becomes phosphorylated, trapped, and nonmetabolized within cells, for the purpose of measuring tissue glucose uptake. Consistent with OGTT glucose data, NC-fed controls and HKDC1Int–/– mice showed no differences in blood levels of nonphosphorylated 14C 2-dOg during the OGTT (Fig. 4A), nor any change in rate of 14C 2-dOg appearance during the first 15 minutes (Fig. 4C) or second 15 minutes (Fig. 4E) post-glucose load. In contrast, HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice demonstrated increased nonphosphorylated 14C 2-dOg levels compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice during the OGTT (Fig. 4B), which was due to an increased rate of appearance of 14C 2-dOg during the first 15 minutes (Fig. 4D). The rate of 14C 2-dOg appearance in the blood did not differ during the second half of the OGTT time course (Fig. 4F). These patterns were maintained when measured 14C 2-dOg in the blood are reported as milligrams of radiolabeled glucose bolus per milliliter of blood (see supplemental Fig. 2A and B (34)). These results suggest that intestinal HKDC1 has a role in glucose absorption in mice chronically fed HFD.

Figure 4.

HKDC1Int–/– mice chronically fed HFD exhibit increased levels of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-O-glucose (14C 2-dOg) in the blood following a radiolabeled glucose load. After a 16-hour overnight fast, a glucose load supplemented with 14C 2-dOg was administered to 28-week-old chow-fed (A) or HFD-fed (B) mice and blood measurements of 14C 2-dOg were made every 5 minutes into the OGTT until 30 minutes and reported here as disintegrations per minute (dpm) per 3 µL of blood. The rate of blood 14C excursion (dpm/3 µL blood/minutes) within the first 15 minutes following the radiolabeled glucose load is shown using blood 14C data from 0- and 15-minute time points (C, D). The rate of blood 14C excursion (dpm/3 µL blood/minute) between 15 and 30 minutes following the radiolabeled glucose load is shown using blood 14C data from 15- and 30-minute time points (E, F). n = 5-6 for chow-fed mice, n = 6-8 for HFD-fed mice. All data are reported as the mean ± SEM. * P < .05, Student’s t test, for glucose rates and area under the curve; OGTT data analyzed by RM 2-way ANOVA.

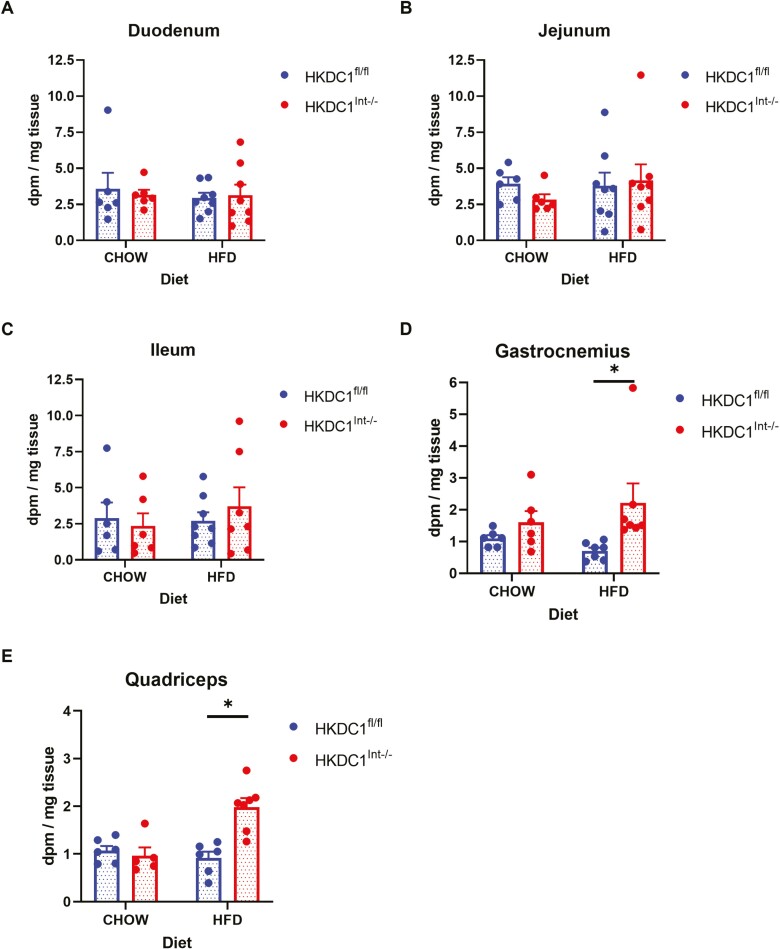

We next assessed if the increased glucose excursion seen in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice was a result of altered tissue utilization of glucose. We assessed glucose uptake within the epithelium of the small intestine by analyzing mucosal scrapings from the duodenum (Fig. 5A), jejunum (Fig. 5B), and ileum (Fig. 5C) for phosphorylated 14C 2-dOg. We found that glucose utilization within all portions of the small intestine were similar regardless of diet or intestinal HKDC1 status. This finding correlates with the finding that HK mRNAs within the small intestine are not altered based on intestinal HKDC1 presence or absence (Fig. 1B and 1C).

Figure 5.

Utilization of 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-O-glucose in the small intestine, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps. Thirty minutes into a radiolabeled OGTT, mice were euthanized, and the 3 portions of the small intestine, namely, the duodenum (A), jejunum (B), and ileum (C), as well as the gastrocnemius (D) and quadriceps (E) muscles were homogenized, supernatants were placed onto anion-exchange columns, eluted, and the amount of phosphorylated (trapped) 2-[1-14C]-deoxy-O-glucose was measured and presented as dpm per mg of tissue sample. n = 5-6 for chow-fed mice, n = 6-8 for HFD-fed mice. All data are reported as the mean ± SEM. *P < .05, Student t test.

Next, we examined whether alteration in glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, which accounts for 80% to 90% of glucose uptake in the postprandial state (37, 38) could result in the enhanced glucose excursion seen in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice. We assessed mouse gastrocnemius (Fig. 5D) and quadriceps (Fig. 5E) muscles 30 minutes after introduction of a radiolabeled glucose load. We found that glucose uptake was similar in mice on NC regardless of intestinal HKDC1 status. On the other hand, HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice exhibited increased glucose uptake compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice, suggesting increased skeletal muscle glucose utilization and hence the increased glucose excursion seen in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice is not a result of impeded skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

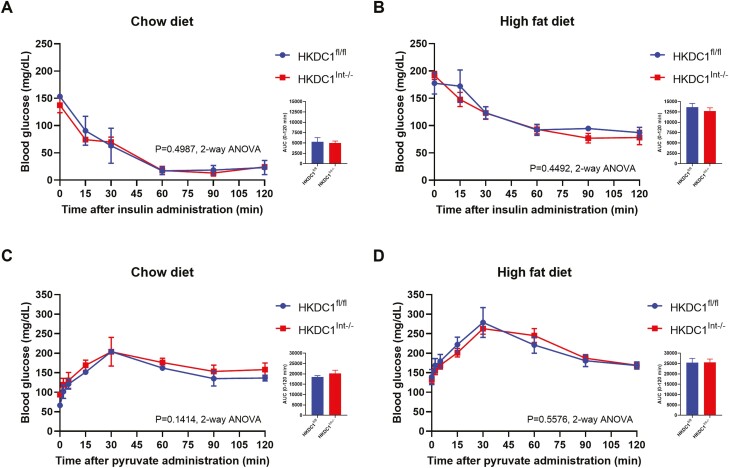

Other factors that could affect blood glucose levels include changes in insulin sensitivity or gluconeogenesis. Insulin tolerance testing (Fig. 6A and 6B) and pyruvate challenge studies (Fig. 6C and 6D) demonstrated no difference in insulin sensitivity or gluconeogenesis, respectively, in the presence or absence of intestinal HKDC1. Reduced insulin sensitivity in HFD-fed mice (Fig. 6B) compared with NC-fed mice (Fig. 6A) is likely due to the chronic effects of the diet. Active GLP-1 levels in HFD-fed mice both prior to and 15 minutes into an OGTT were similar between HKDC1Int–/– and HKDC1fl/fl mice (see supplemental Fig. 3 (34)). Collectively, these data suggest that the effect of intestine-specific HKDC1 on whole body glucose homeostasis occurs at the level of the intestinal epithelium, and, given comparable enterocyte glucose utilization, that intestinal HKDC1 may affect the transport of glucose across the intestinal epithelium.

Figure 6.

Assessment of blood glucose levels in 28-week-old mice after administration of insulin or sodium pyruvate. To assess insulin sensitivity (A, B) and gluconeogenesis (C, D), mice were administered 0.75 units/kg body weight Humalog insulin by injection after a 6-hour fast and 2 mg/g sodium pyruvate orally after an overnight 16-hour fast, respectively. Blood glucose (mg/dL) levels were assessed at various time points. n = 4 for ITT experiments, n = 4-9 for pyruvate challenge experiments. All data are reported as the mean ± SEM. * P < .05, Student’s t test, for area under the curve; insulin tolerance tests and pyruvate challenge studies were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA.

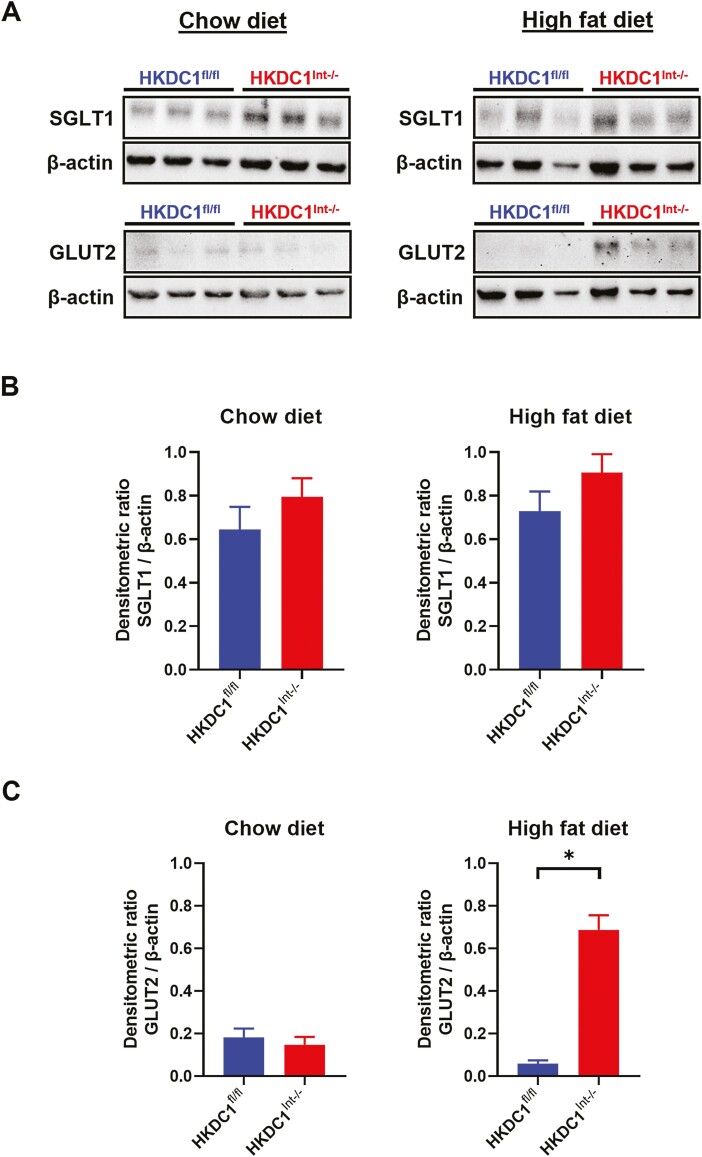

Intestinal Apical Membrane GLUT2 Expression Is Increased in the Fasting State in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– Mice

Since the rate of glucose excursion following an oral glucose load is significantly greater in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– within the first 15 minutes into the OGTT, we next examined if there were differences in apical expression of the main glucose transporters, SGLT1 and GLUT2, after an overnight fast. BBMVs from the proximal half of the small intestine, where most of a glucose load is absorbed, were purified and examined following a 16-hour overnight fast. In both NC- and HFD-fed mice, apical surface SGLT1 trended higher in HKDC1Int–/– mice but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7A, upper panels, and 7B). Apical GLUT2 expression in NC-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice was comparable to HKDC1fl/fl mice (Fig. 7A, lower left panel, and 7C, left graph). Interestingly, HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice had significantly more apical expression of GLUT2 in the fasting state compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice (Fig. 7A, lower right panel, and Fig. C, right graph). This suggests that intestinal HKDC1 plays a role in the regulation of GLUT2 in mice chronically fed a HFD.

Figure 7.

Intestinal brush border expression of the glucose transporters, SGLT1 and GLUT2, in HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice after an overnight fast. After an overnight 16-hour fast, chow- and HFD-fed mice were euthanized, intestines collected, processed, and brush border membrane vesicles purified as described in the text. Immunoblotting was performed in samples for SGLT1 and GLUT2 (A). Densitometric analyses were performed, normalizing SGLT1 (B) and GLUT2 (C) protein levels to β-actin. n = 3 biological replicates, *P < .05, Student’s t test for densitometric analyses.

Discussion

Glucose enters the body through absorption at the intestinal brush border (39). The resultant postprandial hyperglycemic excursions in a person with diabetes can lead to high glycemic variability, increased HbA1c, and increased risk of diabetic complications and cardiovascular disease (13, 16). Current medications available to curb intestinal glucose absorption are limited by gastrointestinal side effects (19, 20). Therefore, a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying intestinal glucose absorption is warranted to elucidate more potential targets for preventing exaggerated postprandial glycemic excursions.

HKDC1 is a novel HK that is widely expressed in a multitude of tissues in humans and mice (21, 23). Prior studies demonstrated a role for HKDC1 in whole-body glucose utilization during pregnancy and with advancing age (23). Here, we specifically focused on intestinal HKDC1 and its role in glucose homeostasis by examining an intestinal HKDC1 knockout mouse model. We examined the role of intestinal HKDC1 in mice fed NC vs mice fed HFD, to simulate an obesogenic state. Although no overt baseline glycemic phenotype was observed based on intestinal HKDC1 status, we found that HFD-fed mice lacking intestinal HKDC1 exhibited a larger glucose excursion during an OGTT, mainly due to increased rate of glucose transport within the first 15 minutes. This finding was not a result of differential glucose utilization by the intestine, impeded glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, or alterations in insulin secretion, global insulin tolerance, or gluconeogenesis. Furthermore, the response to an oral glucose load only differed in mice chronically fed a HFD. Altogether, these results suggest that intestine-specific HKDC1 is important for modulating postprandial glycemic control in an obesogenic state.

It is interesting to note that our data suggests that intestinal HKDC1 plays an overt role in intestinal glucose transport in an obese state, but not in mice fed NC. Obesity is a state of chronic low-grade inflammation which increases cellular stress (40). Within the intestine, chronic HFD feeding increases proinflammatory cytokines and intestinal barrier permeability, promotes dysbiosis and higher levels of “proinflammatory” microbiota (41, 42). These changes place enhanced stress on the intestinal epithelium. In the absence of intestinal HKDC1, the increased glucose excursion observed may be due to dysregulated glucose transport or increased paracellular transport (43). In either situation, there is reduced blood glucose excursion in the blood when intestinal HKDC1 is present, suggesting that intestinal HKDC1 may function as a glucose sensor and confer a protective effect on whole body glucose homeostasis in the presence of intestinal stress by modulating glucose entry into the body.

We observed that in HFD-fed mice, HKDC1Int–/– mice exhibited increased skeletal muscle glucose uptake 30 minutes following a radiolabeled OGTT compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice. This finding may be a result of the increased blood glucose levels postglucose load, but may also suggest differential utilization of glucose by peripheral tissues in the absence of intestinal HKDC1 or differences in insulin- or noninsulin-mediated muscle glucose uptake and warrants further investigation (44-46). Whole-body insulin tolerance tests performed here suggest that systemic insulin resistance is similar in HFD-fed mice regardless of intestinal HKDC1 status, but this does not specifically assess muscle insulin sensitivity. This finding does show that increased glucose excursion in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice is not a result of impeded skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

Although we demonstrate that intestine-specific HKDC1 has an important role in the modulation of glucose homeostasis following an oral glucose load in HFD-fed mice, the precise mechanism by which this occurs remains to be elucidated, but may involve regulation of intestinal glucose transport. The predominant route for the absorption of a dietary glucose load is via apical SGLT1 (47). In the fasting state, SGLT1 is located predominately in the intracellular compartment with some apical expression, with greater abundance and apical surface expression observed in HFD-fed mice and individuals with diabetes (48, 49). Here, we demonstrated that following an overnight fast, the amount of apical SGLT1 is comparable between mice expressing or lacking intestinal HKDC1, regardless of diet, suggesting that the amount of surface SGLT1 available to absorb glucose at the beginning of an OGTT is similar between HKDC1fl/fl and HKDC1Int–/– mice. Prior studies have demonstrated a rise in apical SGLT1 abundance during an OGTT, suggesting the possible modulation of intermediates regulating the SGLT1 exocytotic pathway (50, 51). Future studies would be beneficial to assess the localization and apical surface presence of SGLT1 throughout an OGTT to assess precisely whether HKDC1 has a role in SGLT1-mediated glucose uptake.

GLUT2 primarily provides basolateral exit for glucose into the portal blood but also translocates to the apical membrane to participate in diffusive absorption of glucose at high luminal concentrations (39, 52, 53). Since the rate of glucose excursion was significantly elevated within the OGTT’s first 15 minutes in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice, and since baseline apical SGLT1 expression was comparable with controls, we also examined apical GLUT2 expression. In the fasting state, GLUT2 is mainly found on the basolateral membrane and in intracellular vesicles, with apical translocation regulated by SGLT1-mediated glucose absorption (54). However, in diabetes- and insulin-resistant states, higher levels of apical GLUT2 have been observed, regardless of fasting or nutrient intake (55, 56). We found that HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice had significantly greater expression of apical GLUT2 compared with HKDC1fl/fl mice after an overnight fast, suggesting that chronically HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice have an immediate higher capacity to absorb glucose during an OGTT. This correlates with the enhanced rate of blood glucose excursion seen within the first 15 minutes after the glucose gavage in HFD-fed HKDC1Int–/– mice. The mechanisms by which HKDC1 could modulate GLUT2-mediated glucose transport under normal and obesogenic conditions requires further investigations.

In this study, a significant role for intestinal HKDC1 in glucose homeostasis was found only in mice chronically fed HFD; however, 2 other studies mentioned earlier showed significance for HKDC1 in mice fed NC. First, global knockdown of HKDC1 produced a similar increased glucose excursion following a glucose load in 28-week-old and pregnant mice fed NC (23). Second, a study assessing the role of hepatic HKDC1 on glucose homeostasis in pregnancy demonstrated that hepatic overexpression of HKDC1 improves whole-body glucose tolerance, and enhances hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity, whereas hepatic knockout of HKDC1 achieved the opposite (28). The former study differs from ours in that HKDC1 expression was reduced in all tissues, not just the intestine. In the NC-fed state, intestinal HKDC1 knockout may be compensated by differences in tissue glucose utilization or other mechanisms to maintain whole-body glucose homeostasis. The latter study shows a parallel to our results in that expression of HKDC1 improves overall glycemic control compared with HKDC1 knockout. More studies are needed to elucidate the function of HKDC1 in major glucose-handling tissues and to determine if HKDC1 in various organs function in tandem such that potentiating HKDC1 function may improve glycemic control in obesity and diabetes.

In conclusion, we have provided the first characterization of the function of intestine-specific HKDC1 on intestinal glucose handling and whole-body glucose homeostasis. Our data indicate that intestinal HKDC1 is a modulator of postprandial glucose absorption and asserts its greatest effects in a diseased state, such as obesity. The net effect of intestinal HKDC1 appears to be an improvement in glucose control, as a smaller blood glucose excursion is seen during an OGTT in the chronically diseased state in the presence of HKDC1, suggesting that intestine-specific HKDC1 may be involved in sensing of a dietary glucose load and/or modulation of glucose transporter localization, trafficking, or overall function. Studies aimed at further elucidating the precise mechanisms of intestinal HKDC1 in modulation of intestinal/whole body glucose regulation, as well as an examination of HKDC1 function in major glucose-handling tissues that express HKDC1, are needed to determine the utility of HKDC1 targeting or potentiation as a potential therapeutic for glycemic control.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. George Kyriazis (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) for his guidance in BBMV purification.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 14C 2-dOg

2-[1-14C]-deoxy-O-glucose

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BBMV

brush border membrane vesicle

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HK

hexokinase

- HKDC1

hexokinase domain containing protein-1

- NC

normal chow

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- PPH

postprandial hyperglycemia

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Funding

The studies described in this paper were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32HL139439. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additionally, Brian T. Layden is supported by National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DK104927 and P30DK020595; and Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, VA merit (grant no. 1I01BX003382).

Author Contributions

J.L.Z performed the experiments, statistical analyses, and prepared the manuscript. B.W. assisted in the performance of radiolabeled OGTTs and associated statistical analyses. B.W. and B.T.L critically reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosures

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author (B.T.L.) upon request.

Ethics

All animal experimentation described in the submitted manuscript was conducted in accord with accepted standards of humane animal care.

References

- 1. Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kohnert KD, Augstein P, Heinke P, et al. Chronic hyperglycemia but not glucose variability determines HgbA1c levels in well-controlled patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(3):420-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kohnert KD, Augstein P, Zander E, et al. Glycemic variability correlates strongly with postprandial β-cell dysfunction in a segment of type 2 diabetic patients using oral hypoglycemic agents. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1058-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith-Palmer J, Brändle M, Trevisan R, Federici MO, Liabat S, Valentine W. Assessment of the association between glycemic variability and diabetes-related complications in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105(3):273-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gorst C, Kwok CS, Aslam S, et al. Long-term glycemic variability and risk of adverse outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2354-2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skriver MV, Sandbaek A, Kristensen JK, Stovring H. Relationship of HgbA1c variability, absolute changes in HgbA1c, and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes: a Danish population-based prospective observational study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015;3(1):e000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wan EY, Fung CS, Fong DY, Lam CL. Association of variability in hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular diseases and mortality in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus—a retrospective population-based cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30:1240-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scognamiglio R, Negut C, De Kreutzenberg SV, Tiengo A, Avogaro A. Postprandial myocardial perfusion in healthy subjects and in type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation 2005;112:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Standl E, Schnell O, Ceriello A. Postprandial hyperglycemia and glycemic variability—should we care. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 2):S120-S127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Su G, Mi S, Tao H, et al. Association of glycemic variability and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mi SH, Su G, Li Z, et al. Comparison of glycemic variability and glycated hemoglobin as risk factors of coronary artery disease in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. Chin. Med. J 2012;125(1):38-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frontoni S, Di Bartolo P, Avogaro A, Bosi E, Paolisso G, Ceriello A. Glucose variability: an emerging target for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102(2):86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ceriello A, Monnier L, Owens D. Glycaemic variability in diabetes: clinical and therapeutic implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(3):221-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rieg JAD, Rieg T. What does SGLT1 inhibition add: prospects for dual inhibition. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(Suppl 2):43-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Combs CA, Gunderson E, Kitzmiller JL, Gavin LA, Main EK. Relationship of fetal macrosomia to maternal postprandial glucose control during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(10):1251-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ceriello A. Postprandial hyperglycemia and diabetes complications: is it time to treat? Diabetes. 2005;54(1):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kinsley B. Achieving better outcomes in pregnancies complicated by type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl D):S153-S160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M. Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP-NIDDM trial. JAMA 2003;290(4):486-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DiNicolantonio JJ, Bhutani J, O’Keefe JH. Acarbose: safe and effective for lowering postprandial hyperglycemia and improving cardiovascular outcomes. Open Heart 2015;2(1):e000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garg SK, Henry RR, Banks P, et al. Effects of sotagliflozin added to insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(24):2337-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Irwin DM, Tan H. Molecular evolution of the vertebrate hexokinase gene family: identification of a conserved fifth vertebrate hexokinase gene. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 2007;3(1):96-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guo C, Ludvik AE, Arlotto ME, et al. Coordinated regulatory variation associated with gestational hyperglycemia regulates expression of the novel hexokinase HKDC1. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ludvik AE, Pusec CM, Priyadarshini M, et al. HKDC1 is a novel hexokinase involved in whole-body glucose use. Endocrinology 2016;157(9):3452-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan MW, Ding X, Cotler SJ, Clarke M, Layden BT. Studies on the tissue localization of HKDC1, a putative novel fifth hexokinase, in humans. J Histochem Cytochem. 2018;66(5):385-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hayes MG, Urbanek M, Hivert M-F, et al. 2013 Identification of HKDC1 and BACE2 as genes influencing glycemic traits during pregnancy through genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3282-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kanthimathi S, Liju S, Laasya D, Anjana RM, Mohan V, Radha V. Hexokinase domain containing 1 (HKDC1) gene variants and their association with gestational diabetes Mellitus in a South Indian Population. Ann Hum Genet. 2016;80(4):241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan YX, Hu SM, You YP, Yang GL, Wang W. Replication of previous genome-wide association studies of HKDC1, BACE2, SLC16A11 and TMEM163 SNPs in a gestational diabetes mellitus case-control sample from Han Chinese population. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes 2019;12:983-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khan MW, Priyadarshini M, Cordoba-Chacon J, Becker TC, Layden BT. Hepatic hexokinase domain containing 1 (HKDC1) improves whole body glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in pregnant mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865(3):678-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, Braunstein K, Braunstein E, Gumucio DL. cis Elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):33275-33283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):270-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J, Wu H, Liu Y, Yang L. High fat diet induced obesity model using four strains of mice: Kunming, C57BL/6, BALB/c and ICR. Exp Anim. 2020;69(3):326-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mull AJ, Berhanu TK, Roberts NW, Heydemann A. The Murphy Roths Large (MRL) mouse strain is naturally resistant to high fat diet-induced hyperglycemia. Metabolism 2014;63(12):1577-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heydemann A. An Overview of Murine High Fat Diet as a Model for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2902351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zapater JL, Wicksteed B, Layden BT. Data from: Enterocyte HKDC1 modulates intestinal glucose absorption in male mice fed a high-fat diet. Figshare data repository. Deposited 21 January 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.18858647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35. Bergman RN. Orchestration of glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2007;56(6):1489-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao C, Yang C, Wai STC, et al. Regulation of glucose metabolism by bioactive phytochemicals for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;59(6):830-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):S157-S163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fujimoto BA, Young M, Nakamura N, et al. Disrupted glucose homeostasis and skeletal-muscle-specific glucose uptake in an exocyst knockout mouse model. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Röder PV, Geillinger KE, Zietek TS, Thorens B, Koepsell H, Daniel H. The Role of SGLT1 and GLUT2 in intestinal glucose transport and sensing. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holvoet P. Stress in obesity and associated metabolic and cardiovascular disorders. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:205027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Duan Y, Zeng L, Zheng C, et al. Inflammatory links between high fat diets and diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barakat B, Almeida MEF. Biochemical and immunological changes in obesity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;708:108951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gromova LV, Fetissov SO, Gruzdkov AA. Mechanisms of glucose absorption in the small intestine in health and metabolic diseases and their role in appetite regulation. Nutrients 2021;13(7):2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pereira LO, Lancha AH. Effect of insulin and contraction up on glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;84(1):1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rose AJ, Richter EA. Skeletal muscle glucose uptake during exercise: How is it regulated? Physiology 2005;20:260-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pereira RM, de Moura LP, Muñoz VR, et al. Molecular mechanisms of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle at rest and in response to exercise. Motriz: Rev. Educ. Fis. 2017;23:e101609. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen L, Tuo B, Dong H. Regulation of intestinal glucose absorption by ion channels and transporters. Nutrients 2016; 8(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Veyhl-Wichmann M, Friedrich A, Vernaleken A, et al. Phosphorylation of RS1 (RSC1A1) steers inhibition of different exocytotic pathways for glucose transporter SGLT1 and nucleoside transporter CNT1, and an RS1-derived peptide inhibits glucose absorption. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;89(1): 18-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hu Z, Liao Y, Wang J, Wen X, Shu L. Potential impacts of diabetes mellitus and anti-diabetes agents on expressions of sodium-glucose transporters (SGLTs) in mice. Endocrine 2021;74(3):571-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gorbulev V, Schürmann A, Vallon V, et al. Na(+)-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes. 2012;61(1):187-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koepsell H. Glucose transporters in the small intestine in health and disease. Pflügers Arch. 2020;472(9):1207-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E. Apical GLUT2: A Major Pathway of Intestinal Sugar Absorption. Diabetes. 2005;54(10):3056-3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wright EM, Loo DDF, Hirayama BA. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):733-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kellett GL, Brot-Laroche E, Mace OJ, Leturque A. Sugar Absorption in the Intestine: The Role of GLUT2. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:35-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Corpe CP, Basaleh MM, Affleck J, Gould G, Jess TJ, Kellett GL. The regulation of GLUT5 and GLUT2 activity in the adaptation of intestinal brush-border fructose transport in diabetes. Phlugers Arch. 1996;432(2):192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tobin V, Le Gall M, Fioramonti X, et al. Insulin internalizes GLUT2 in the enterocyte of healthy but not insulin-resistant mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(3):555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets that support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author (B.T.L.) upon request.