Abstract

Background

To evaluate the association between immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and the clinical outcomes and also between irAEs and the post-treatment changes in the relative eosinophil count (REC) in advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC) patients treated with pembrolizumab.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study analyzed 105 advanced UC patients treated with pembrolizumab after disease progression on platinum-based chemotherapy between January 2018 and June 2021. The association between the occurrence of irAEs and the efficacy of pembrolizumab was investigated. The change in the REC from before the initiation of pembrolizumab therapy, to three weeks after treatment and the incidence of irAEs were determined.

Results

Overall irAEs were associated with a significantly higher objective response rate (ORR) (58.8% vs 25.4%, P<0.001), a longer progression-free survival (PFS) (25.1 months vs 3.1 months, P< 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (31.2 months vs 11.5 months, P< 0.001) compared to patients without irAEs; however, grade ≥3 irAEs were not associated with the ORR (36.4% vs 36.2%, P=0.989), PFS (9.5 vs 5.5 months, P=0.249), or OS (not reached vs 13.7 months, P=0.335). Compared to a decreased REC at 3 weeks after pembrolizumab, an increased relative REC at 3 weeks was not associated with the incidence of any-grade irAEs (32.3% vs 32.5%, P=0.984) or of grade ≥3 irAEs (10.8% vs 10.0%, P=0.900). Multivariate analyses revealed a female sex (P=0.005), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status ≥1 (P=0.024), albumin <3.7 g/dl (P<0.001), decreased REC (3 weeks later) (P<0.001), and the absence of irAEs of any grade (P=0.002) to be independently associated with a worse OS.

Conclusion

Patients with irAEs showed a significantly better survival compared to patients without irAEs in advanced UC treated with pembrolizumab. An increased posttreatment REC may be a marker predicting improved clinical outcomes and it had no significant relationship with the incidence of irAEs.

Keywords: urothelial carcinoma, pembrolizumab, immune-related adverse events, relative eosinophil count

Introduction

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has markedly changed the treatment of many types of tumors, with a subset of patients with advanced cancer, including advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC), showing improved survival.1–6 The Phase III KEYNOTE-045 study demonstrated that, in comparison to chemotherapy, pembrolizumab (a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets programmed death receptor-1 [PD-1]), significantly improved overall survival in patients who had received first-line platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced UC.5 The assessment of health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) in the KEYNOTE-045 trial demonstrated that pembrolizumab increased the time to the deterioration of the HRQoL, in addition to improving or stabilizing the patient’s global health status/quality of life in comparison to chemotherapy.7 While the tolerability profile of pembrolizumab was superior to that of conventional chemotherapy, ICIs have the potential to cause various toxicities and adverse effects, termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs), when normal organs are attacked as a result of immune system activation.8

Recently, several studies have reported a possible association between the incidence of irAEs and the clinical efficacy of ICIs in patients with melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer.8–10 Also in UC, a relationship between irAEs and the outcomes of ICIs has been reported; however, few of these studies have investigated UC and the relationship remains unclear.11,12 Furthermore, a number of clinical biomarkers of the response to ICIs have been reported for advanced UC,13–16 and we previously reported that an increased relative eosinophil count (REC) after three weeks of pembrolizumab treatment may be associated with improved clinical outcomes.17 However, it is still unclear whether an increased REC would cause increased numbers of irAEs or specific irAEs.

In the present study, we retrospectively investigated the association between irAEs and oncological outcomes, and whether an increased REC is associated with increased irAEs or any specific irAEs in advanced UC patients treated with pembrolizumab.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The records of advanced UC patients who received pembrolizumab treatment after disease progression on platinum-based chemotherapy from January 2018 to June 2021 were analyzed. The patients were managed at 6 institutions. Pembrolizumab was administered intravenously at a fixed dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks, until the occurrence of disease progression or adverse events that were deemed unacceptable. Computed tomography was generally performed before treatment and after every 4–6 treatment cycles, or when it was deemed to be clinically necessary. We evaluated the tumor response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1.18 As reported previously,19,20 the peripheral REC was measured at the same time as complete blood count measurements: before treatment and at three weeks after the start of pembrolizumab treatment. The patients’ clinical information and follow-up data were obtained from their medical records. The grades of irAEs were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0.21 irAEs were categorized as skin, endocrine, gastrointestinal, respiratory, hepatobiliary and other disorders. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before their inclusion in this study. The present retrospective study was approved by the National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (approval no. 2020–90) and the ethics committee of each institution.

Statistical Analyses

An increased REC was defined as an increased REC at 3 weeks after the initial pembrolizumab treatment in comparison to the pretreatment REC. A decreased REC was defined as a decreased or unchanged REC at 3 weeks after initial pembrolizumab treatment in comparison to the pretreatment REC. The objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the percentage of pembrolizumab-treated patients who showed a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR). Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the association between the ORR and the incidence of overall and individual irAEs, and to analyze the differences in overall and individual irAEs between the increased REC and decreased REC groups. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the start of pembrolizumab treatment until the date of disease progression or death. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of pembrolizumab until death from any cause. PFS and OS curves were determined by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by a Log rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP® Pro (version 15.1.0, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 125 patients with advanced UC received pembrolizumab after disease progression on platinum-based chemotherapy. The patients were managed at 6 institutions. After the exclusion of 20 patients due to missing clinical data, 105 patients were included in the analysis (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 72 years (interquartile range [IQR], 67–77 years), and 75 (71.4%) patients were men. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) was 0 in 64 patients (61.0%) and ≥1 in 41 patients (39.0%). A histological analysis demonstrated pure transitional cell features in 85 (81.0%) patients. The locations of the tumor included the bladder in 42 patients (40.0%), the upper urinary tract in 41 patients (39.0%), and both bladder and upper urinary tract in 22 patients (21.0%). Visceral metastasis was present in 61 patients (58.1%), and liver metastasis was present in 19 patients (18.1%). Pembrolizumab was administered as a second-line treatment to 84 patients (80.0%). The evaluation of the change in REC at 3 weeks after the initiation of pembrolizumab revealed an increased REC in 65 (61.9%) patients. irAEs of any grade occurred in 34 patients (32.4%), with grade ≥3 irAEs occurring in 11 patients (10.5%). The ORR was 36.2% (n=38).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics (n=105) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 72 (67–77) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 75 (71.4) |

| ECOG PS score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 64 (61.0) |

| 1 | 31 (29.5) |

| ≥2 | 10 (9.5) |

| Primary tumor site, n (%) | |

| Bladder | 42 (40.0) |

| Upper urinary tract | 41 (39.0) |

| Upper urinary tract + bladder | 22 (21.0) |

| Pure UC in histological analysis, n (%) | 85 (81.0) |

| Albumin (g/dl), median (IQR) | 3.8 (3.5–4.2) |

| Visceral metastasis | 61 (58.1) |

| Liver metastasis | 19 (18.1) |

| Treatment line of pembrolizumab | |

| 2nd | 84 (80.0) |

| ≥3rd | 21 (20.0) |

| Increased posttreatment REC (3 weeks later) | 65 (61.9) |

| irAEs | |

| Any grade | 34 (32.4) |

| Grade ≥3 | 11 (10.5) |

| ORR(CR+PR) | 38 (36.2) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; UC, urothelial carcinoma; REC, relative eosinophil count; irAEs, immune-related adverse events; ORR, objective response rate; CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

Profiles of irAEs in Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab

The profile of the irAEs is shown in Table 2. Overall irAEs occurred in 34 (32.4%) patients; 11 (10.5%) patients experienced severed irAEs (grade ≥3). Skin-related (n=15) and endocrine system-related (n=11) irAEs were the most common types of any-grade irAEs. Grade ≥3 irAEs included gastrointestinal disorder (n=3), respiratory disorder (n=3), endocrine disorder (n=2), skin disorder (n=1), myositis (n=1), and myocarditis (n=1).

Table 2.

Types of Immune-Related Adverse Events (Any-Grade and Grade≥3)

| Type of irAEs | Any-Grade, n (%) | Grade ≥ 3, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall irAEs | 34 (32.4) | 11 (10.5) |

| Skin | 15 (14.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Endocrine | 11 (10.5) | 2 (1.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (6.7) | 3 (2.9) |

| Respiratory | 4 (3.8) | 3 (2.9) |

| Hepatobiallary | 2 (1.9) | 0 |

| Other disorder | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.9) |

| Myositis | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Myocarditis | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 (1.0) | 0 |

| Infusion-related reactions | 1 (1.0) | 0 |

Abbreviation: irAEs, immune-related adverse events.

Association Between the ORR and irAEs and Between the ORR and the Change of the REC in Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab

The ORR was 36.2%, with CR and PR rates of 4.8% and 31.4%, respectively. The ORR of patients with any-grade irAEs was significantly higher than that of patients without irAEs (58.8% vs 25.4%, P=0.001). However, the ORR of patients with and without grade ≥3 irAEs did not (36.4% vs 36.2%, P=1.000). The ORR was significantly higher in patients with an increased post-treatment REC in comparison to patients with a decreased post-treatment REC (44.6% vs 22.5%, P=0.024) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Between Immune-Related Adverse Events and the Objective Response Rate and Between Immune-Related Adverse Events and the Increased Post-Treatment Relative Eosinophil Count

| ORR, % | No. of Patients (Responders/Total) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 36.2 | 38/105 | |

| Any-grade irAEs | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 58.8 | 20/34 | |

| No | 25.4 | 18/71 | |

| Grade ≥3 irAEs | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 36.4 | 4/11 | |

| No | 36.2 | 34/94 | |

| Increased posttreatment REC (3 weeks later) | 0.024 | ||

| Yes | 44.6 | 29/65 | |

| No | 22.5 | 9/40 |

Abbreviations: ORR, objective response rate; irAEs, immune-related adverse events.

Association Between irAEs and Post-Treatment (Three Weeks Later) REC Changes in Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab

There was no significant difference in the incidence rate of irAEs of any grade between patients with an increased post-treatment REC and those with a decreased post-treatment REC (32.3% vs 32.5%, P=1.000). Regarding the individual irAEs in patients with an increased post-treatment REC and those with a decreased post-treatment REC, there were no significant differences in the rates of skin (18.5% vs 7.5%, P=0.156), endocrine (7.7% vs 15.0%, P=0.326), gastrointestinal (4.6% vs 10.0%, P=0.423), respiratory (4.6% vs 2.5%, P=1.000), or hepatobiliary (0% vs 5.0%, P=0.143) irAEs. There was no significant difference in the incidence rate of grade ≥3 irAEs between patients with an increased post-treatment REC and those with a decreased post-treatment REC (10.8% vs 10.0%, P=1.000) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association Between the Incidence of Immune-Related Adverse Events and the Change in the Post-Treatment Relative Eosinophil Count

| Increased REC (n=65) | Decreased REC (n=40) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any-grade irAEs, n (%) | 21 (32.3) | 13 (32.5) | 1.000 |

| Skin | 12 (18.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0.156 |

| Endocrine | 5 (7.7) | 6 (15.0) | 0.326 |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (4.6) | 4 (10.0) | 0.423 |

| Respiratory | 3 (4.6) | 1 (2.5) | 1.000 |

| Hepatobiallary | 0 | 2 (5.0) | 0.143 |

| Grade 3 irAEs, n(%) | 7 (10.8) | 4 (10.0) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: irAEs, immune-related adverse events; REC, relative eosinophil count.

Association Between irAEs and Survival in Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab

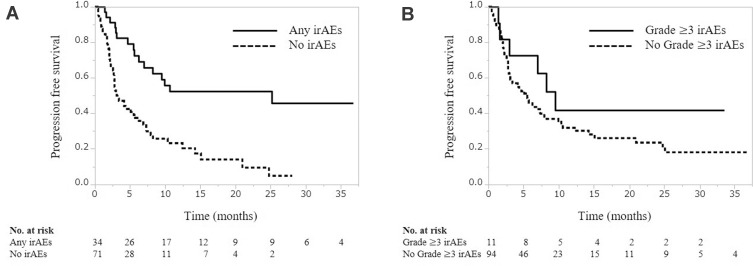

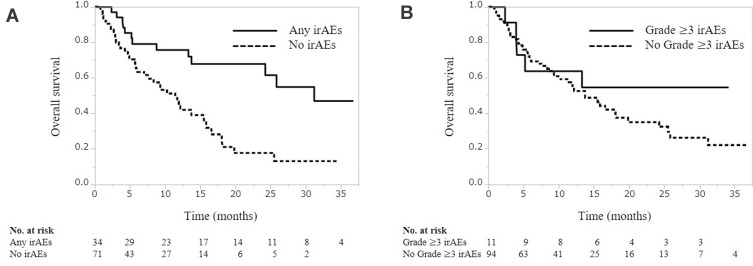

During a median follow-up period of 8.4 months (IQR, 4.1−15.7 months), the median PFS and OS were 3.3 months (IQR, 2.8–5.5) and 13.7 months (IQR, 10.2–19.8), respectively. PFS was significantly associated with the occurrence of any-grade irAEs (25.1 months vs 3.1 months, P<0.001, Figure 1A), but not with the occurrence of grade ≥3 irAEs (9.5 vs 5.5 months, P=0.249, Figure 1B). Similarly, OS was significantly associated with the occurrence of any-grade irAEs (31.2 months vs 11.5 months, P<0.001, Figure 2A), but not with the occurrence of grade ≥3 irAEs (not reached vs 13.7 months, P=0335, Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival according to the occurrence of any-grade (A) and grade≥3 (B) immune-related adverse events.

Figure 2.

Overall survival according to the occurrence of any-grade (A) and grade≥3 (B) immune-related adverse events.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of OS in Pembrolizumab-Treated Patients

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors (Table 5). In the multivariate analyses, female sex (hazard ratio [HR] 2.274, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.278–4.048, P=0.005), ECOG PS ≥1 (HR 1.975, 95% CI: 1.095–3.561, P=0.024), albumin <3.7 g/dl (HR 3.377, 95% CI: 1.816–6.281, P<0.001), decreased post-treatment REC (at 3 weeks after the initiation of treatment) (HR 3.073, 95% CI: 1.775–5.318, P<0.001), and the absence of any-grade irAEs (HR 2.885, 95% CI: 1.465–5.683, P=0.002) were independently associated with decreased OS.

Table 5.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Associated with Overall Survival in Pembrolizumab-Treated Patients

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | <75 years | 1 | |||

| ≥75 years | 1.268 (0.732–2.196) | 0.397 | |||

| Sex | Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 2.141 (1.244–3.687) | 0.006 | 2.274 (1.278–4.048) | 0.005 | |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1 | 2.836 (1.663–4.837) | <0.001 | 1.975 (1.095–3.561) | 0.024 | |

| Primary tumor site | Bladder | 1 | |||

| Upper urinary tract | 1.327 (0.728–2.419) | 0.356 | |||

| Bladder + upper urinary tract | 1.116 (0.544–2.287) | 0.765 | |||

| Histology | Pure UC | 1 | |||

| Mixed UC | 0.750 (0.367–1.534) | 0.431 | |||

| Albumin | ≥3.7 g/dl | 1 | 1 | ||

| <3.7 g/dl | 3.408 (1.959–5.929) | <0.001 | 3.377 (1.816–6.281) | <0.001 | |

| Visceral metastasis | Absent | 1 | |||

| Present | 1.099 (0.642–1.884) | 0.729 | |||

| Posttreatment REC (3 weeeks later) | Increased | 1 | 1 | ||

| Decreased | 2.797 (1.643–4.763) | <0.001 | 3.073 (1.775–5.318) | <0.001 | |

| Any-grade irAEs | Present | 1 | 1 | ||

| Absent | 2.911 (1.528–5.548) | 0.001 | 2.885 (1.465–5.683) | 0.002 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; UC, urothelial carcinoma; REC, relative eosinophil count; irAEs, immune-related adverse events.

Discussion

In the present study, the relationship between irAEs and the clinical outcomes, and the relationship between the occurrence of irAEs and the change in the REC were retrospectively evaluated in advanced UC patients who received pembrolizumab after disease progression during treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy. The present study revealed that irAEs of any grade were associated with a significantly higher ORR, longer PFS, and longer OS in comparison to patients without irAEs. Moreover, an increased REC at 3 weeks after the initiation of pembrolizumab therapy did not result in the numbers of irAEs or in the occurrence of specific irAEs. Our results revealed a strong association between the incidence of irAEs and the clinical efficacy of pembrolizumab. Furthermore, an increased REC after the initiation of treatment could be a predictive marker for improved clinical outcomes and did not have a significant relationship with an increase in the number of irAEs or in the occurrence of specific irAEs in advanced UC patients who received pembrolizumab subsequent to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Although ICI therapy is associated with significantly improved outcomes in patients with various malignancies, including advanced UC, they have the potential to induce irAEs, which may limit their application. The exact mechanisms that underlie the development of irAEs remain to be fully uncovered; however, in an association between the development of irAEs and improved outcomes has been reported in patients who receive ICI therapy for various types of cancer, including melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer.22–25 irAEs have been reported to be associated with improved clinical efficacy in UC who receive ICI therapy; however, few studies have investigated this phenomenon.11,12,14 In the present study, the multivariate analysis demonstrated that the absence of any-grade irAEs was independently associated with worse OS (HR 2.885, P=0.002). Thus, in line with previous studies that investigated the use of ICIs in various types of cancer, the results of the present study support an association between the occurrence of irAEs and the clinical efficacy of ICI therapy in UC patients.

Although the present study confirmed an association between any-grade irAEs and the clinical efficacy of pembrolizumab, this association was not confirmed for grade ≥3 irAEs. In patients who received nivolumab monotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, the PFS of patients with irAEs was reported to be longer in comparison to patients without irAEs regardless of the severity of their irAEs (grade ≥3 vs no irAEs; P=0.0023; grade <3 vs no irAEs: P=0.0024). Furthermore, the incidence of grade <3 irAEs rather than grade ≥3 was associated with longer OS (grade <3 vs no irAEs: P=0.0124; grade ≥3 vs no irAEs: P=0.136).26 On the other hand, in patients receiving combination therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, it was reported that PFS of patients with grade ≥3 irAEs was significantly longer in comparison to patients with grade <3 irAEs (p=0.0388) or patients without irAEs (P<0.0001); however, the same association was not observed for OS.27 In patients receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy for stage III melanoma, it was reported that the occurrence of an irAE was associated with longer recurrence-free survival in the pembrolizumab arm (P=0.03), but the occurrence of a severe (grade 3–4) irAE among patients treated with pembrolizumab therapy was not significantly associated with prolonged RFS (P=0.43).28 This difference seen with regard to the grades of irAEs and the efficacy of ICI therapy may be attributable to the different ICI regimens that the patients received; that is, the presence of irAEs themselves—not necessarily severe irAEs—may be a clinical biomarker that predicts favorable outcomes in patients with advanced UC who receive pembrolizumab.

Complete blood analyses are routinely performed for patients undergoing immunotherapy and the eosinophil count can be easily measured in clinical practice. Eosinophils are a subset of granulocytic leukocytes with important roles in parasitic and allergic disease.29 Recently, eosinophils have been highlighted as potential cellular biomarkers and even end-stage effector cells in cancer therapy.30–33 Eosinophilia has also been reported to be closely associated with clinical efficacy in patients undergoing ICI therapy for melanoma,34 lung cancer,35 renal cell carcinoma,36 and classical Hodgkin lymphoma.37 Furthermore, we recently reported that an increased REC after pembrolizumab treatment was associated with superior OS in comparison to a decreased REC in advanced UC patients who received pembrolizumab therapy.17

While eosinophilia has been reported as a prognostic and predictive marker of cancer outcomes, it is also reported closely associated with irAEs. Among patients with non–small cell lung cancer who received treatment with ICIs (all patients were treated with PD-1 inhibitors either as monotherapy (44.7%) or in combination with chemotherapy or anti-angiogenesis therapy), a baseline feature of high absolute eosinophil count (≥0.125 × 109 cells/L) was associated with an increasing risk of ICI-pneumonitis, but also with a better clinical outcome.38 Another study reported that irAEs are more common in patients with peripheral eosinophilia, and that eosinophilia is significantly associated with cutaneous irAEs, advanced melanoma patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors who developed any type of cutaneous irAE showing better overall survival.39 In another study in which the majority of patients had melanoma or non-small lung cancer with ICIs (the majority received PD-1 inhibitors, but the study population also included patients treated with a cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 [CTLA-4] inhibitor, the combination of CTLA4 and PD-1 inhibitors, and PD-L1 inhibitors), eosinophilia (≥0.5 × 109 cells/L) during treatment was found to be significantly associated with the incidence of any-grade toxicity. Severe toxicity was not associated with eosinophilia. Disease control was more likely to be achieved in patients who developed eosinophilia.40

In the present study, we also retrospectively analyzed the association between the incidence of irAEs and the change in REC after treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab) and observed that an increased post-treatment REC at 3 weeks was not associated with an increased number of irAEs or specific irAEs including respiratory disorder and skin-related irAEs. Differences in various factors, including the type of cancer, type of ICI, timing of measurement of the REC, and ethnicity, may have led to differences in the clinical outcomes of the present study and previous studies. Given that our previous report suggested that an increased post-treatment REC (3 weeks later) was an independent prognostic factor for better OS, an increased REC after treatment could be an early predictor of improved clinical outcomes but is not associated with an increased number of irAEs or specific irAEs in patients with advanced UC who receive pembrolizumab.

The present study was associated with some limitations. First, this retrospective study had a relatively small study population; thus, there may have been a selection bias. Second, this was a multi-institutional study, and the patients were not enrolled in clinical trials; thus, there was heterogeneity in the regimens and lines of systemic chemotherapy that the patients had received, and in the evaluation and management of irAEs. Prospective studies with larger cohorts and a long follow-up period are necessary to confirm the findings of the present study.

Conclusion

In patients with advanced UC who received pembrolizumab after platinum-based chemotherapy, the incidence of irAEs was associated with a significantly higher ORR, longer PFS, and longer OS in comparison to patients without irAEs. An increased posttreatment REC could also be a marker to predict improved clinical outcomes and did not have a significant relationship with the incidence of irAEs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Japan Medical Communication (https://www.japan-mc.co.jp/) for editing the English language of the present manuscript.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Abbreviations

ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; UC, urothelial carcinoma; PD-1, programmed death receptor-1; irAEs, immune-related adverse events; REC, relative eosinophil counts; ORR, objective response rate; PFS, progression‑free survival; OS, overall survival; IQR, interquartile range; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4.

Ethics Approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center (2020-90). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial disclosures or potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonia S, Villegas A, Danie D, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, Phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellmunt J, Wit RD, Vaughn DJ, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1015–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1218–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaughn DJ, Bellmunt J, Fradet Y, et al. Health-related quality-of-life analysis from KEYNOTE-045: a phase III study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously treated advanced urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(16):1579–1587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, et al. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):886–894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374–378. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato K, Akamatsu H, Murakami E, et al. Correlation between immune-related adverse events and efficacy in non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2018;115:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi K, Suzuki K, Hiraide M, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with pembrolizumab efficacy in the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Oncology. 2020;98(4):237–242. doi: 10.1159/000505340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kijima T, Fukushima H, Kusuhara S, et al. Association between the occurrence and spectrum of immune-related adverse events and efficacy of pembrolizumab in asian patients with advanced urothelial cancer: multicenter retrospective analyses and systematic literature review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19(3):208–216.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sacdalan DB, Lucero JA, Sacdalan DL. Prognostic utility of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:955–965. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S153290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai T, Sato Y, Makino K, et al. Immune-related adverse events predict the therapeutic efficacy of pembrolizumab in urothelial cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:114–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasuoka S, Yuasa T, Nishimura N, et al. Initial experience of pembrolizumab therapy in Japanese patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(7):3887–3892. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogihara K, Kikuchi E, Shigeta K, et al. The pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a novel biomarker for predicting clinical responses to pembrolizumab in platinum-resistant metastatic urothelial carcinoma patients. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(6):602.e1–602.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furubayashi N, Minato A, Negishi T, et al. The association of clinical outcomes with posttreatment changes in the relative eosinophil counts and neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:8049–8056. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S333823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohashi H, Takeuchi S, Miyagaki T, et al. Increase of lymphocytes and eosinophils, and decrease of neutrophils at an early stage of anti-PD-1 antibody treatment is a favorable sign for advanced malignant melanoma. Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14(3):117–121. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.03043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mota JM, Teo MY, Whiting K, et al. Pretreatment eosinophil counts in patients with advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother. 2021;44(7):248–253. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services. NIoH, National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0; 2017. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2021.

- 22.Cortellini A, Chiari R, Ricciuti B, et al. Correlations between the immune-related adverse events spectrum and efficacy of anti-PD1 immunotherapy in NSCLC patients. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(4):237–247.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisschop C, Wind TT, Blank CU, et al. Association between pembrolizumab-related adverse events and treatment outcome in advanced melanoma: results from the Dutch expanded access program. J Immunother. 2019;42(6):208–214. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3193–3198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toi Y, Sugawara S, Kawashima Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with clinical benefit in patients with advanced non-small-cell Lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Oncologist. 2018;23(11):1358–1365. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(6):355.e21–355.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda T, Ishihara H, Nemoto Y, et al. Prognostic impact of immune-related adverse events in metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(10):735.e9–735.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggermont AM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(4):519–527. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon SC, Utikal J, Umansky V. Opposing roles of eosinophils in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(5):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2255-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon HU, Plötz S, Simon D, et al. Interleukin-2 primes eosinophil degranulation in hypereosinophilia and Wells’ syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(4):834–839. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sosman JA, Bartemes K, Offord KP, et al. Evidence for eosinophil activation in cancer patients receiving recombinant interleukin-4: effects of interleukin-4 alone and following interleukin-2 administration. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(8):805–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellem KA, O’Rourke MG, Johnson GR, et al. A case report: immune responses and clinical course of the first human use of granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating-factor-transduced autologous melanoma cells for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;44(1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s002620050349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gebhardt C, Sevko A, Jiang H, et al. Myeloid cells and related chronic inflammatory factors as novel predictive markers in melanoma treatment with Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(24):5453–5459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weide B, Martens A, Hassel JC, et al. Baseline biomarkers for outcome of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(22):5487–5496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanizaki J, Haratani K, Hayashi H, et al. Peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zahoor H, Barata PC, Jia X, et al. Patterns, predictors and subsequent outcomes of disease progression in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0425-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hude I, Sasse S, Bröckelmann PJ, et al. Leucocyte and eosinophil counts predict progression-free survival in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin Lymphoma patients treated with PD1 inhibition. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(6):837–840. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu X, Zhao J, Zhou J, et al. Association of baseline peripheral-blood eosinophil count with immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis and clinical outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2020;150:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bottlaender L, Amini‑Adle M, Maucort‑Boulch D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events: a predictor of tumour response under anti‑PD‑1 therapy for metastatic melanoma, a cohort analysis of 189 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(9):2096–2105. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnan T, Tomita Y, Roberts-Thomson R, et al. A retrospective analysis of eosinophilia as a predictive marker of response and toxicity to cancer immunotherapy. Future Sci OA. 2020;6(10):FSO608. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]