Abstract

The organic solar cell (OSC) is a current hot topic in the context of energy related issues in order to capture energy in an economic and environmentally friendly manner from the most abundant natural source, the sun. However, the efficiency of OSCs achieved so far is not up to the mark. Major components of OSCs are the electron acceptor material, such as fullerene, and the electron donor material, such as poly(3-hexylthiophene), P3HT. Fullerene is an ideal acceptor material but molecular level engineering of P3HT is required to enhance the efficiency of OSCs. Optoelectronic properties of P3HT can be improved by controlling the regioregularity, energy band gap, and molar mass of the polymer. Additionally, p-doping of the semiconducting polymer can also help in broadening the optical spectrum of P3HT. In this study, we propose methods for the improvement of the above-mentioned properties during the synthesis of P3HT. The main focus was the improvement of the regioregularity of the synthesized P3HT, which was achieved by polymerization of 3-hexylthiophene under an electric field for the first time. The effect of molar mass and p-doping on the band gap is evaluated systematically and theoretical predictions are confirmed by experimental results.

The regioregularity and band gap of P3HT, an organic solar cell donor polymer, were improved. Oxidative coupling enhanced regioregularity, voltammetric p-doping broadened the optical absorption band and a molar mass increase reduced the band gap.

1. Introduction

Global warming and environmental pollution are major problems of the modern world. The main reason for these problems is the use of fossil fuels to produce non-renewable energy. As an alternative, solar energy is one of the most abundant renewable energy sources that can be utilized without any hazardous effects to the environment.1,2 The manufacture of commercially available inorganic silicon solar cells involves the release of hazardous chemicals to the environment. Organic solar cells (OSCs) are an alternative to inorganic silicon solar cells, which are non-hazardous and comparatively cheap.2,3 However, the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of organic solar cells is low compared to inorganic solar cells. The PCE of organic solar cells can be improved by chemical modification of the conjugated polymer used in the organic solar cell as an electron donor along with fullerene as an excellent electron acceptor material.4,5

Polythiophenes are semiconducting organic macromolecules that are environment friendly, cost-effective, easily processible and thermally stable, hence, are excellent candidates as electron donor for organic electronic devices such as OSC.6 Poly(3-hexylthiophene), P3HT, is the most widely employed p-type donor material. However, large energy band gap (∼2.0 eV) and relatively higher HOMO energy level (∼5.0 eV) are the limitations associated with P3HT. Higher energy band gap hamper efficient absorption of the most part of solar radiations (red and infrared region) that is supposed to be the major reason of lower efficiency of P3HT. The maximum flux density of solar spectrum is found around 700 nm, equivalent to 1.7 eV.7 The lowering of energy band gap of P3HT can improve the absorption efficiency. In order to improve absorption of more dense part of solar radiation, donor material (P3HT) can be modified by three means; (1) by compressing HOMO–LUMO energy levels, (2) by decreasing LUMO energy, and (3) by increasing HOMO energy. Peet et al. claimed 5.5% power conversion efficiency (PCE) by using poly[2,6-(4,4-bis-(2-ethylhexyl)-4H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b′]dithiophene)-alt-4,7-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)], PCPDTBT, which is a donor–acceptor conjugated polymer.8 This improvement of efficiency was due to lower energy band gap of the polymer, 1.46 eV. Improved efficiency was also reported by using poly[2,7-(9,9-dioctylcarbazole)-alt-4,7-bis(thiophen-2-yl)benzo-2,1,3-thiadiazole], PCzDTBT as conjugated polymer, which has lower HOMO energy level, −5.5 eV.9 The efforts to improve PCE of organic solar cell by engineering of conjugated polymers are recently summarized.4,10

Above-mentioned improvements in PCE were attained by utilizing completely different, complex and expensive polymers. Lower band gap can also be realized by tuning the molecular parameters such as molar mass and regioregularity of most widely employed polymer for this purpose, P3HT. Higher molar mass P3HT exhibit longer conjugation length and therefore have lower energy band gap.11–13 Voltammetric p-type doping can also improve optoelectronic properties. The absorption spectrum of P3HT can be broadened by p-doping that allows capturing broad region of solar spectrum compared to parent neutral P3HT.13–17

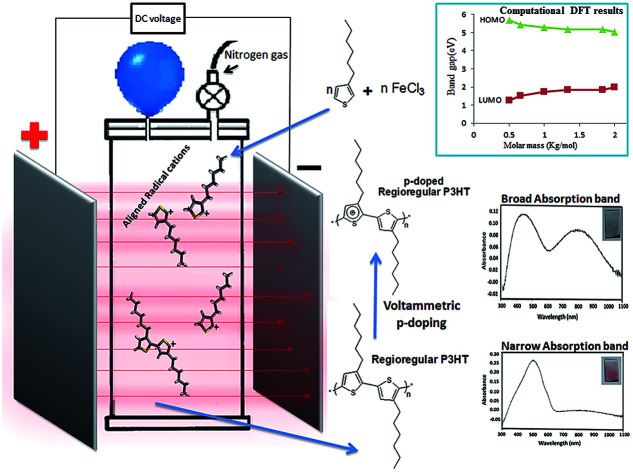

The mobility of excitons can be enhanced by controlling regioregularity of P3HT. Several different methods are reported for synthesis of highly regioregular P3HT.18,19 However, these methods require sensitive and highly expensive catalysts that are not feasible for industrial production. Oxidative coupling by anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3) is the simplest and cost-effective synthetic procedure for P3HT.20 Limitations of this method include comparatively less controlled process resulting in broad molar mass and low regioregular P3HT. However, regioregularity of the synthesized P3HT can be improved by lowering monomer concentration, temperature and slow mixing of reactants.21,22 Another method is post-polymerization washing with proper solvents.22 Nevertheless, further modifications in the method are required for synthesis of P3HT with controlled molar mass and regioregularity. Another viable option could be application of external electric field (EEF) for alignment of transition state intermediate during the course of polymerization.23–27 The first monomer should be converted into cationic radical under uniform EEF by transfer of electron to Fe3+. These cationic radicals get aligned under influence of EEF that should allow head to tail addition of next monomer resulting in regioregular P3HT.

In this study, we target controlled synthesis of P3HT with improved regioregularity by employing simple and cost-effective oxidative coupling method. Energy band gap, HOMO and LUMO energy levels of synthesized P3HT under different conditions are evaluated as a function of molar mass and p-doping. Computational simulations of relation of molar mass with energy band gap were followed by synthesis of P3HT. Density functional theory (DFT) was employed to study geometries and Frontier orbitals of P3HT. Among available quantum chemical methods, density functional theory (DFT) has shown significant promise for monitoring changes in electronic structure.28 In density functional theory, DFT, the energy of the fundamental state of a polyelectronic system can be expressed as the total electronic density, therefore, it is used as electron density instead of a wave function for calculating the energy, constitutes the fundamental basis of DFT. Different parameters during polymerization such as sonication, stirring, and external electric field (EEF) were evaluated for their effects on regioregularity of the synthesized polymers. Furthermore, energy band gap are assessed as a function of molar mass and p-doping. A feasible method to reduce the energy band gap is p-doping. Electrochemical p-doping is a process of positive holes generation by electrochemical oxidation of conjugated polymer.29 Up to the best of our knowledge, the utilization of electric field for improvement of regioregularity of P3HT has never been reported. Molar mass of synthesized polymer was deduced by size exclusion chromatography while regioregularity is monitored by proton NMR and energy levels are examined by cyclic voltammetry and UV-vis near IR spectroscopy.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

3-Hexylthiophene (99%) and indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass slides were purchased from Ossila, UK. Anhydrous ferric chloride (98%) was purchased from RDH, Germany. Tetrabutyl ammonium perchlorate, and acetone were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Methanol (CH3OH), and chloroform CHCl3 were purchased from Merck. Nitrogen gas (99.99%) was bought from Linde, Pakistan. All the materials were used as received.

2.2. DFT computational calculations

In the present study, DFT in combination with Becke's three parameter exchange functional along with the Lee–Yang–Parr nonlocal correlation functional (B3LYP)36 with the 6-311G (d,p) basis set was utilized in order to calculate energy of Frontier orbitals and geometries on GaussView 3.0.30,31 Energies were calculated for monomer (3-hexylthiophene), trimer, tetramer and oligomers containing higher number of repeat units.

2.3. Polymerizations

P3HTs were prepared by oxidative coupling of 3-hexylthiophene (monomer) in the presence of FeCl3. The ratio of monomer and FeCl3 was kept 1 : 4 in all cases (Scheme 1). As a general procedure, a reaction flask containing anhydrous FeCl3 suspended in chloroform (CHCl3) was flushed with nitrogen and sealed. The initial concentration of monomer in chloroform was kept 0.05 M in general, unless otherwise specified. The solution of 3-hexylthiophene was added slowly in the suspension of FeCl3 with the help of a syringe. Polymerizations were carried out at room temperature for 24 h under nitrogen atmosphere. The variations in the polymerization conditions are listed in Table 1. The resultant black reaction mixture was poured into methanol for precipitation of polymer. Afterwards, Soxhlet's extractor was used for washing of precipitates by methanol. The polymers were extracted with CHCl3 by using same extractor. Polymer was collected after evaporation of solvent at room temperature.

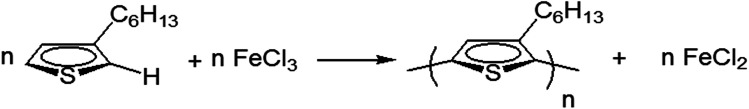

Scheme 1. Synthesis of P3HT by oxidative coupling in presence of FeCl3.

Synthesis protocols, and results of molar mass and regioregularity as obtained by size exclusion chromatography, 1H-NMR and UV/vis spectroscopy.

| Polymer code | Synthesis protocols | Size exclusion chromatography | 1H-NMR | UV/vis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction condition | Monomer concentration (M) | M n (g mol−1) | M w (g mol−1) | D, Mw/Mn | HT, % | HH, % | λ max, (nm) | Optg. (eV) | |

| P3HT-1 | EEF (0 V), no St./So. | 0.05 | 14 500 | 80 600 | 5.5 | 57 | 43 | — | — |

| P3HT-2 | EEF (25 V) | 0.05 | 148 000 | 70 600 | 4.7 | 65 | 35 | — | — |

| P3HT-3 | EEF (100 V) | 0.05 | 19 900 | 77 900 | 3.9 | 74 | 26 | — | — |

| P3HT-4 | EEF (1000 V) | 0.05 | 37 100 | 97 200 | 2.6 | 75 | 25 | — | — |

| P3HT-5 | So. | 0.05 | 2700 | 2800 | 1.0 | 74 | 26 | 431 | 2.88 |

| P3HT-6 | St. | 0.1 | 54 300 | 116 900 | 2.1 | 69 | 31 | 439 | 2.82 |

| P3HT-7 | So. | 0.1 | 83 000 | 114 900 | 1.4 | 76 | 24 | 442 | 2.81 |

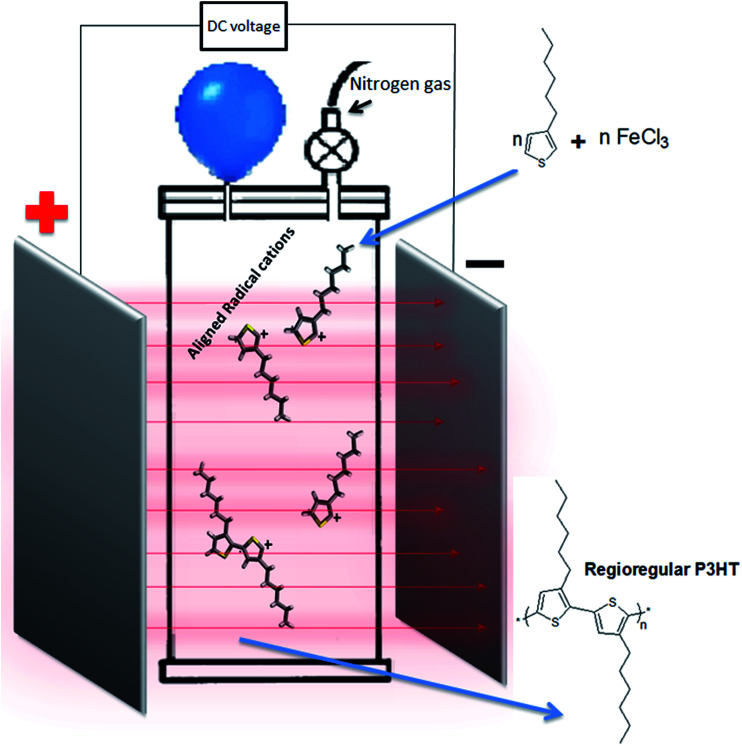

Polymerization under EEF was performed in the same setup. The monomer concentration was kept 0.05 M and reaction time was 24 h at room temperature without sonication/stirring under nitrogen. External DC electric fields of different potential (0 V, 25 V, 100 V, 1000 V) were employed. EEF was applied between two iron plates, placed parallel to each other having 1 cm distance between them, Fig. 7. The method of purification was same as described earlier.

Fig. 7. Schematic diagram of experimental setup for polymerization under EEF.

2.4. Characterization

An Agilent SEC instrument (infinity 1200 series) equipped with an isocratic pump, manual injector, column oven and a RI detector was used for SEC analysis. A set of three PLgel columns (300 × 7.5 mm, 5 μm, Mixed D) connected in front with a PLgel guard column (50 × 7.5 mm) was used. The column oven was maintained at 30 °C. Chloroform (HPLC grade) was used as an eluent at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. The SEC system was calibrated with narrow molar mass polystyrene standards by Polymer Standard Services (Germany). Therefore, all the molar mass values obtained by SEC analysis are relative to linear polystyrene. The data was processed by Agilent OpenLAB ChemStation. Sample concentrations were kept between 3.0 to 10.0 mg mL−1, and 100 μL of sample solution was injected.

Proton NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance AN-500 MHz spectrometer. The polymer fractions were dissolved in CDCl3, and tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as the internal standard. UV-visible-near IR spectra of P3HT fractions were recorded in the wavelength range of 200–1100 nm in CHCl3 solutions. For spectra of solid phases, P3HT were coated by dip coating method on ITO glass slide and spectra were recorded. FT-IR spectroscopic analysis was performed for solution of polymer in chloroform in the spectral range of 4000–500 cm−1.

For cyclic voltammetric studies, the polymer was coated on ITO glass electrode from a solution of P3HT in CHCl3 by dip coating method. Films were dried under air at room temperature. Cell was equipped with polymer coated ITO working electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (0.1 M AgNO3 in water) double junction reference electrode. 0.1 M tetrabutyl ammonium perchlorate, TBAP/acetonitrile solution was used as supporting electrolyte. Potentiostat, CH Instrument, USA, model CHI 660, was used to record voltammograms after purging with nitrogen gas. The potential was scanned from 0 to +2 V followed by +2 to −2 V and finally from −2 to 0 V at scan rate of 100 mV s−1.

p-Doping of the P3HT film was conducted by voltammetry. Three different doping potentials, including 0.00 V, +1.00 V, and +1.25 V, were selected from the cyclic voltammogram of P3HT-6 and resulting polymers were assigned as undoped, partially doped and highly doped, respectively. Each polymer coated ITO glass electrode was disconnected from the potentiostat without changing the specified potential and electrode was rinsed several times with acetonitrile and subsequently dried. The resulting polymer films were subjected to spectroscopic analysis in the range of 300 to 1100 nm. ITO glass electrode without polymer coating was used as blank.

The polymer selected for p-doping is P3HT-6. Polymer was coated on ITO glass slide from polymer solution in chloroform. 0.1 M tetrabutyl ammonium perchlorate (TBAP) in anhydrous acetonitrile was used as supporting electrolyte. Three electrodes system was composed of polymer coated ITO glass slides as working electrode, Ag/AgCl as reference electrode and platinum wire as counter electrode. All three electrodes were immersed in the solution of supporting electrolyte and a constant electrode potential of 0.00 V was applied for 1 min. Thereafter the working electrode was disconnected from the system and optical spectrum was recorded from 300 nm to 1100 nm of undoped P3HT-6. The working electrode was again connected to voltammetric system and constant potential of 1.00 V was applied for p-doping (or oxidation) and once again optical spectrum was measured in the same range. This coated polymer is assigned as partially doped P3HT-6. Same procedure was followed for doping potential of 1.25 V and optical spectrum was measured. The coated polymer is now assigned as highly doped P3HT-6.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization

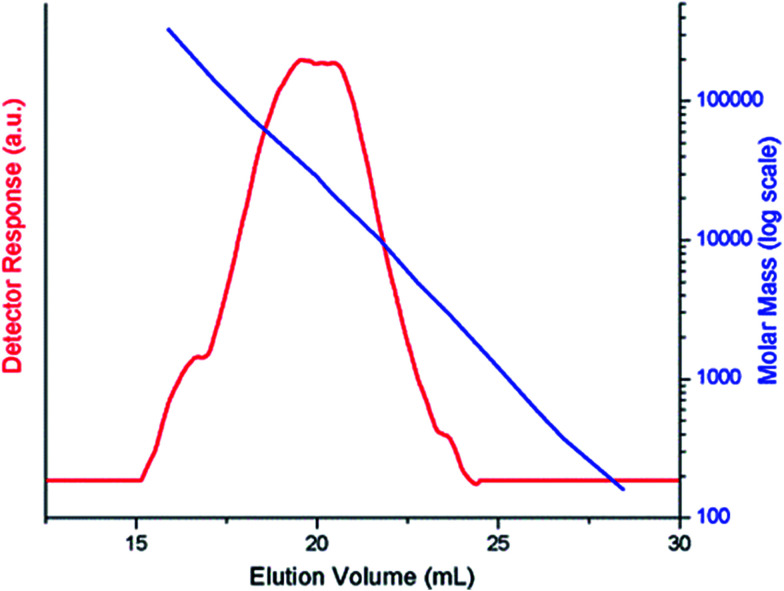

Polymerization of 3-hexylthiophene was conducted by oxidative coupling method using FeCl3. The method is comparatively simple and cheaper, however, this method has limited control over molar mass of polymers and their regioselectivity. In this study, we strive for better control over molar mass and regioselectivity by varying external polymerization parameters such as stirring, sonication, and EEF. The first question about any synthesized polymer has to be the molar mass and its dispersity. One of the foremost limitations of oxidative coupling method is its limited control over molar mass and regioselectivity of the synthesized polymer. In order to evaluate effect of different external parameters on this control, polymers are analyzed by size exclusion chromatography for determination of molar mass. It is pertinent to mention here that the molar mass values obtained in this study are equivalent to linear polystyrene since instrument was calibrated with narrow molar mass polystyrene standards. As a typical example, SEC curve of a P3HT-3 is shown in Fig. 1. The polystyrene calibration curve in the same plot demonstrates relation of elution volume with the molar mass. The molar mass data of all the polymers as obtained by SEC with regard to polystyrene calibration is given in Table 1.

Fig. 1. A typical size exclusion chromatogram, P3HT-3.

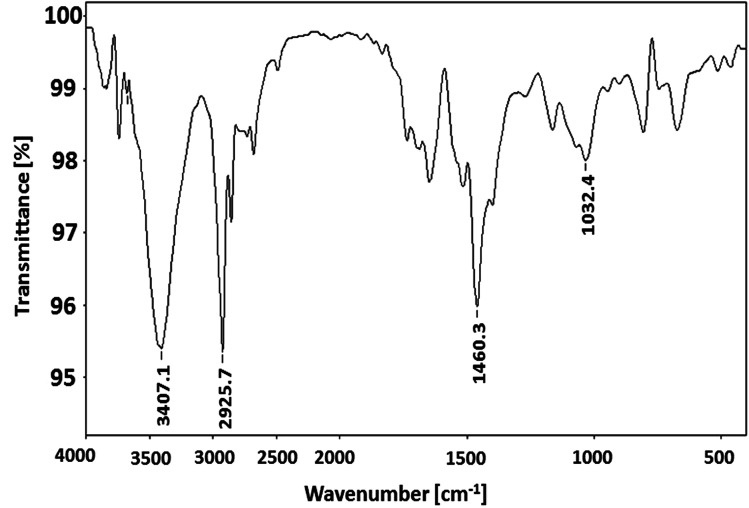

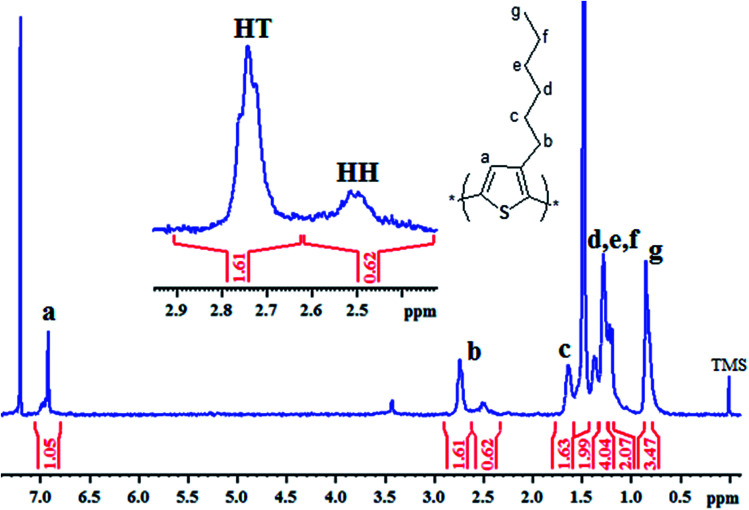

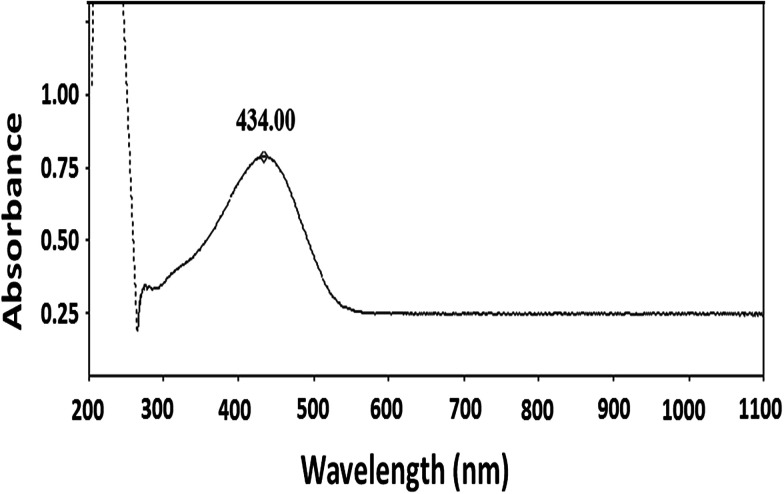

The molecular nature of synthesized polymer is confirmed by FTIR analysis. All the characteristic peaks of P3HT were found in FTIR spectrum, Fig. 2. Peaks at 2925.2 cm−1 and 3400.9 cm−1 are due to C–H vibration in the aliphatic chain of hexyl groups. The peak intensity of this peak is high due to high proportion of carbon–hydrogen bonds in the polymer. Thiophene ring can be identified by peak at 1460.6 cm−1. Presence of C–H of aromatic ring is confirmed by a peak at 1079.0 cm−1.32,33 As mentioned earlier regioregularity of the polymer is another important parameter that needs to be examined carefully for proper functioning of conjugated polymer. Mobility of electron throughout the lattice structure of regioregular conjugated polymer is enhanced by pi stacking between polymers and hence improvement in the optoelectronic properties is expected.34 The planarity of conjugated backbone of polymer is disturbed due to steric repulsions in regiorandom polymer. Therefore, charge carrier mobility is decreased and optoelectronic properties of polymer are suppressed. NMR spectroscopy is a wonderful tool to quantify the regioregularity of the polymers. As a typical example, Fig. 3 depicts 1H-NMR spectrum of P3HT-3. All the characteristic shifts are present as labelled. The head to tail (HT) and head to head (HH) arrangement of repeat units in polymer chain can be calculated from characteristic α-methylene peaks.13,35 The shift in the range of 2.75 to 2.8 ppm is attributed to HT arrangement whereas the peak in the range of 2.5 to 2.6 ppm is due to HH arrangement. The percentage of HH and HT content can be calculated from the relative ratio of the integral of above-mentioned peaks. Optical energy band gap is determined by converting wavelength maximum (nm) into energy (eV), from optical spectrum.13 Optical spectrum for P3HT-3 coated on ITO glass slide is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 2. FT-IR spectra of P3HT-3.

Fig. 3. 1H-NMR spectrum of P3HT-3, inset is the region of interest for calculation of regioregularity of the polymer.

Fig. 4. UV/visible-near-IR spectrum of P3HT-3.

3.2. Theoretical simulations by density functional theory (DFT)

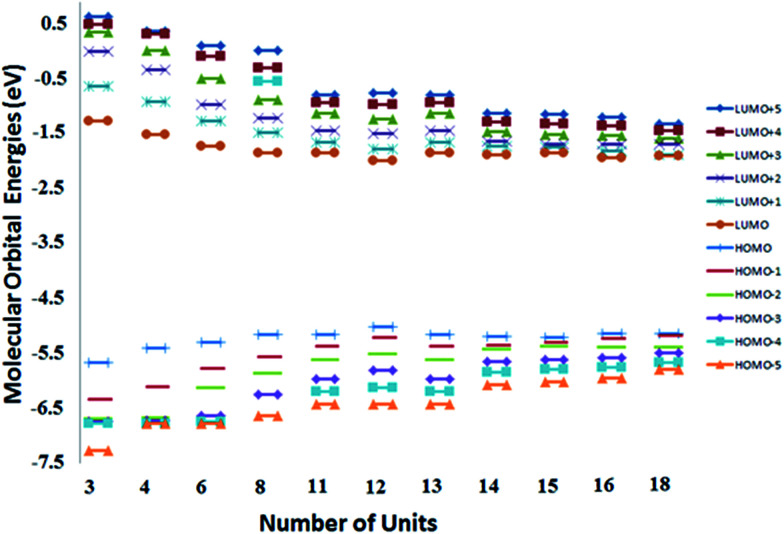

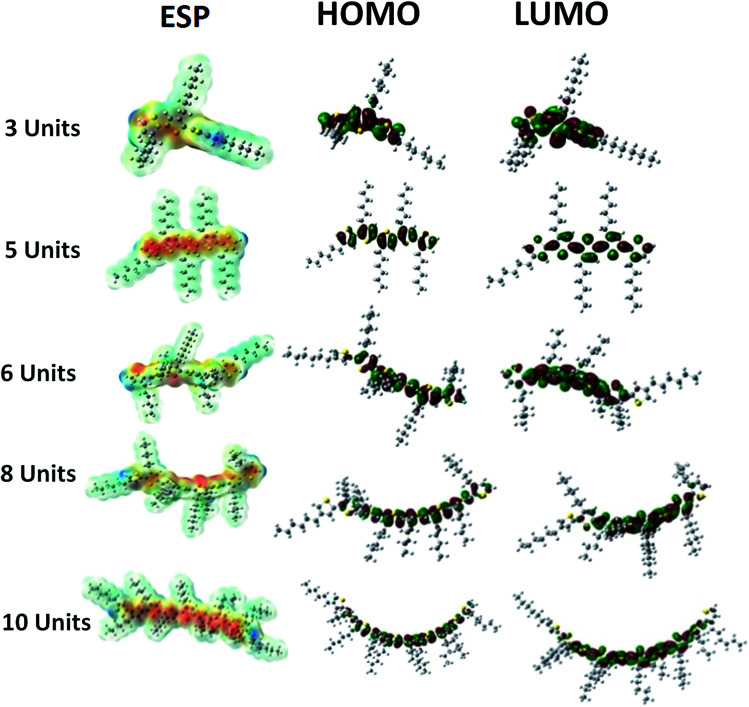

Theoretical simulations reveal that the energy bad gap of electrons compresses with increase in the number of repeat units of conjugated polymer, Fig. 5. Conjugation length of the polymer chain increases with its chain length that induces variations in the bonding (HOMO) and anti-bonding (LUMO) molecular orbital geometries, Fig. 6. The increase in the conjugation length of polymer results in an increase in the HOMO energy level while LUMO energy is decreased at the same time.28 Therefore, the energy band gap decreased with increase in number of repeat units in the conjugated polymer. The band gap of polymer having 12 repeat units is 3.073 eV, large for OSC application. The energy band gap below 1.9 eV is required for improvement of power conversion efficiency. The intense part of solar spectrum is red and near IR that can only be absorbed by polymer having narrow band gap (1.2 to 1.9 eV).4

Fig. 5. Molecular orbital energy diagram of P3HT.

Fig. 6. Dependence of molecular orbitals and electrostatic potential (ESP) on number of repeat units.

3.3. Selectivity of synthesis parameters

To evaluate the selectivity of various experimental parameters, polymerizations are conducted without stirring/sonication (St./So.), with stirring (St.) and with sonication (So.), compare P3HT-1, P3HT-5, and P3HT-6 in Table 1. It can be noticed that sonication during polymerization resulted in highly regioregular and narrowly dispersed polymer. The regioregularity of polymer prepared by polymerization under stirring is better than polymerization without sonication and/or stirring. The reason of improvement in the regioregularity by polymerization under sonication might be attributed to the cavity effect due to which molecules are uniformly dispersed in reaction mixture.36

The effect of concentration of monomer is evaluated by synthesizing P3HT using two different concentrations while keeping other conditions alike, P3HT-5 and P3HT-7. As expected, the molar mass of the polymer synthesized using higher initial concentration of the monomer is higher than the other. This augmentation in the molar mass can be attributed to increased effective collision between the reacting species. Hence, initial concentration of the monomer can be utilized as an effective tool to control the targeted molar mass. However, no significant effect of monomer concentration is noticed on regioregularity. The current results endorse the previous report that regioregularity is not really effected by monomer concentration provided concentration is below 0.5 M.22 As a next step, energy band gaps are compared as a function of molar mass for the polymers prepared under similar conditions, P3HT-5 and P3HT-7. Energy band gap decreased with increase in the molar mass, endorsed the theoretical calculations. The reason of decreased energy band gap might be the increased conjugation length of higher molar mass polymer.11–13

External electric field (EEF) can maneuver the orientation of radical/growing chain and has been employed for synthesis of regioregular polymers of various types.23–25 However, synthesis of P3HT has never been reported under influence of external electric field. The schematic diagram of experimental setup is shown in Fig. 7. EEF has been applied between two metal plates placed 1 cm apart from each other. The regioregularity (head to tail content, HT) of the P3HT synthesized under EEF improved significantly as a function of voltage applied. The most significant effect on the regioregularity is observed from no external field to application of external electric field of 100 V, 57 to 75%, compare P3HT-1 to P3HT-3. Application of stronger electric field (1000 V) does not have any additional significant effect on the regioregularity, compare P3HT-1 to P3HT-4. The effect can be attributed to alignment of cationic radicals under EEF. During polymerization first monomer (3-hexylthiophene) is converted into cationic radical by the transfer of electron to Fe3. All the cationic radicals formed are aligned due to constant electric lines of forces passing through the reaction mixture. Hence cationic radicals are coupled with each other in head to tail orientation.

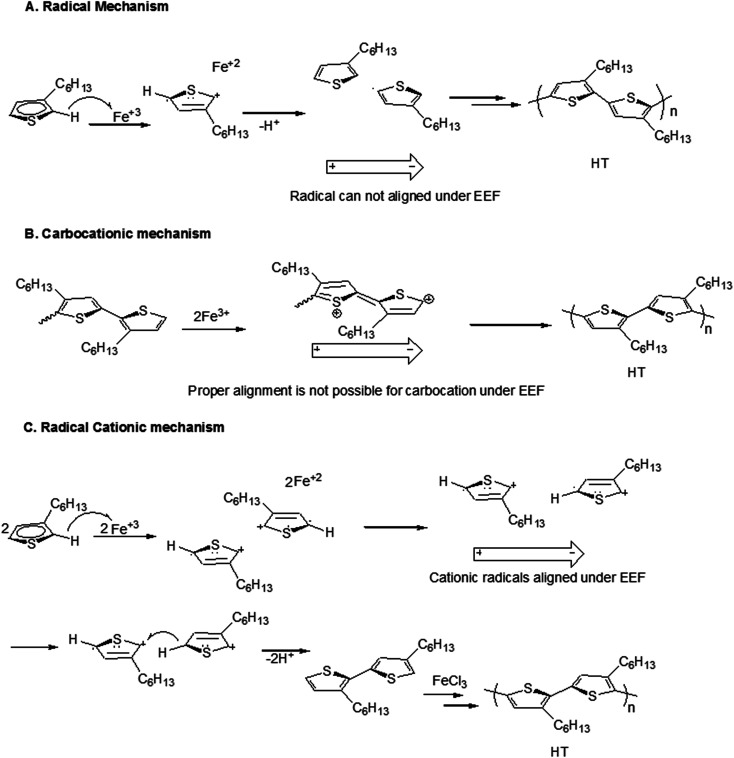

3.4. Mechanism of polymerization under EEF

In this context, three already proposed mechanisms are evaluated for polymerization under influence of EEF; radical mechanism, carbocationic mechanism and radical cationic mechanism. First possible mechanism could be radical initiated, FeCl3 is insoluble in chloroform (polymerization solvent) and therefore it must provide its active surface for monomer. Monomer upon reaching the surface of FeCl3 transfers one of electron to the iron(iii) and converts it into radical cation. Elimination of hydrogen from the ring in the form of hydrogen radical results in formation of monomer radical. Therefore, there can be four species present in the reaction system; neutral monomer, cationic radical, the monomer radical on 5th carbon, and the monomer radical on 2nd carbon. The first assumption could be higher electron density on second carbon of the neutral monomer, Scheme 2A. Each radical carbon is coupled with the 2nd carbon of neutral monomer leading to both head to head (2nd carbon to 2nd carbon) and head to tail (2nd carbon to 5th carbon) dimmers, with varying probabilities. Quantum mechanical calculations reported by Amou et al. revealed that radical at 5th carbon is energetically more stable. Therefore, probability of head to tail coupling is higher.22 However, polymerization proceeds among neutral species by proposed mechanism therefore EEF will not have any effect on the polymerization process.

Scheme 2. Possible mechanisms of polymerization reaction.

Carbocationic mechanism of the oxidative coupling of monomer with FeCl3 is proposed by Andersson et al.21 They used 3-(4-octylphenyl)thiophene monomer, a mono-substituted thiophene derivative. They argued that only carbocation mechanism is responsible for coupling in strong oxidizing environment, Scheme 2B. The improvement in the regioregularity is also reported by slow addition of monomer solution in the suspension of FeCl3. The dipoles of carbocation formed during this mechanism cannot align properly under EEF, therefore, EEF will not have any effect on the polymerization process.

In this context, Barbarella's group proposed radical cationic mechanism by quantum mechanical calculations for oxidative coupling of monomer with FeCl3.37 A mono-substituted thiophene derivative, 3-(alkylsulfanyl)thiophene has been used as monomer. Stable radical chains with increasing conjugation length during polymerization are proposed. The cationic radicals obtained by oxidation of monomer get coupled in head to tail (HT) orientation. Ionic polymerization mechanism leads to the formation of ions during reaction.25 The ions follow the laws of electrochemistry such as molecular alignment of dipolar species under EEF. Since radical cations (charged species) are dipolar and they can be aligned under EEF that results in increased probability of HT couplings. The mechanism justifies the experimental results of increased regioregularity of the polymers synthesized under influence of EEF.

Consequently, an improved regioregularity can be obtained by application of EEF to the oxidative coupling of 3-hexylthiophene with FeCl3. Regioregularity is also enhanced by sonication, hence, synthesis under EEF with sonication could have synergic effect for improvement of regioregularity. The method provides an economical way for synthesize a P3HT with improved regioregularity because it requires low-cost catalyst, ferric chloride (FeCl3) and few synthetic steps. Furthermore, not much purification steps are required. Furthermore, polymerization temperature may also play vital role for enhancement of regioregularity. In this study, the polymerizations were conducted at room temperature. Decrease in reaction temperature might result in improved alignment of cationic radicals, however, reaction rate might be slow. The experimental and theoretical evidences presented in this study shall open new possibilities for regioselective synthetic chemistry.

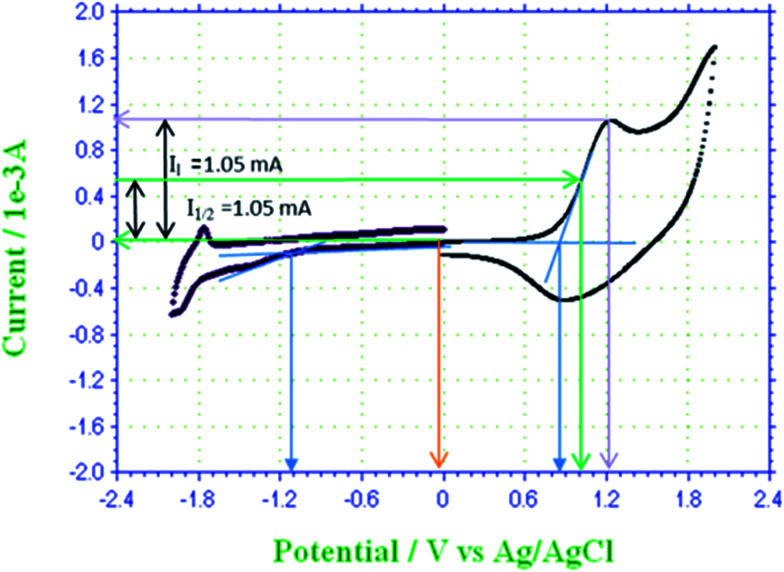

Spectroelectrochemistry, cyclic voltammetry and optical spectroscopy, of P3HT was carried out to study electrical and optical energy band gap of solid thin film.13 Cyclic voltammogram of P3HT-6 is shown in Fig. 8. Voltammogram shows characteristic peaks and similar electrochemical behavior of P3HT as described in the literature.38 Absence of oxidation at 0 V is confirmed by no current at this potential (yellow line). Maximum current is observed at anodic peak potential (violet line) that confirms oxidation of most of the repeat units. The onset potentials (blue lines) of oxidation and reduction are 0.85 V and −1.11 V versus Ag/AgCl, respectively. Electrons are released from the π bonds of thiophene rings in P3HT during oxidation. The homo π-electrons are present in the HOMO energy level and the onset potential required for their oxidation may correspond to the HOMO level. On the other hand, reduction onset potential may correspond to LUMO level because electrons are added to the LUMO.39,40 The obtained electrical energy band gap was 1.96 eV. The optical energy band gap corresponds to the excitation of electrons from HOMO to LUMO, which is found to be 2.46 eV for the same thin film of P3HT.

Fig. 8. Cyclic voltammogram of P3HT-6.

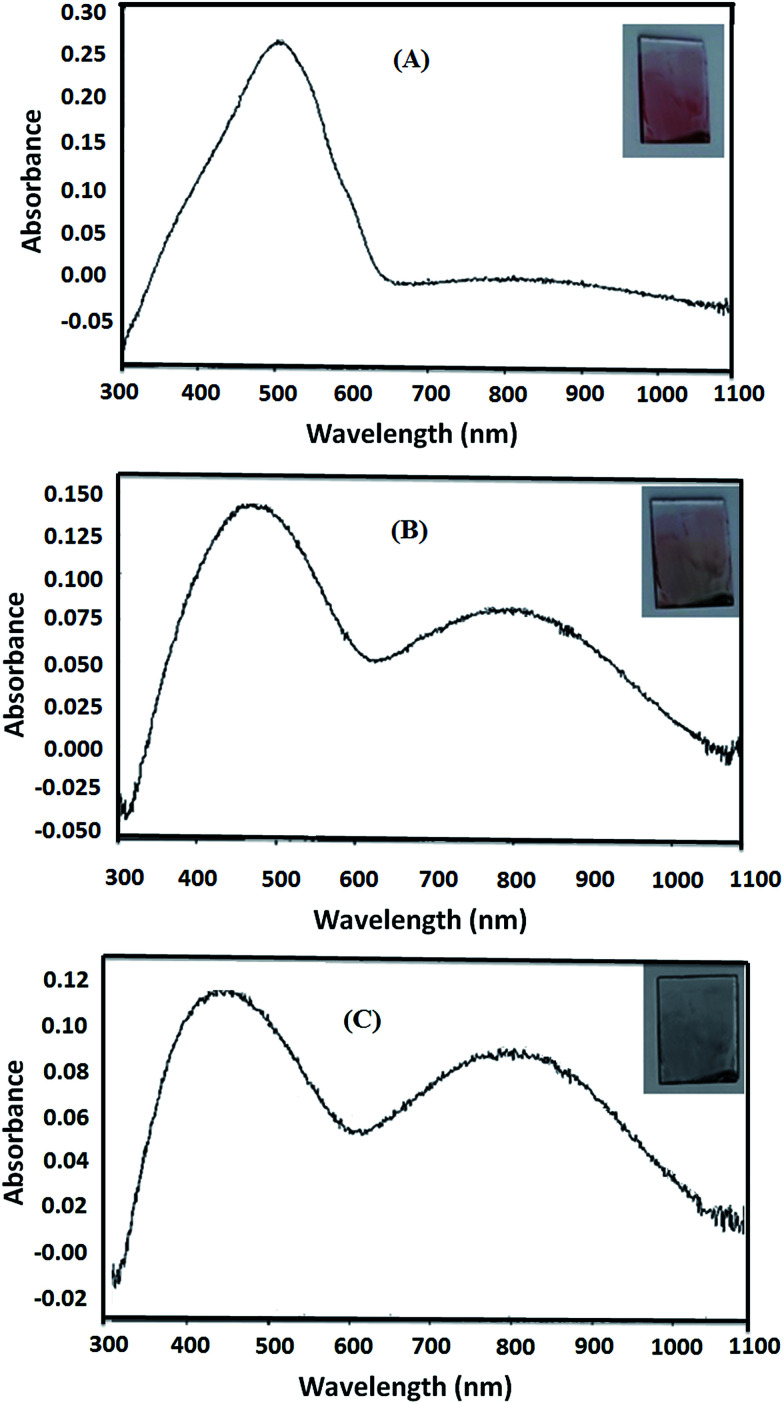

3.5. p-Doping for reduction in energy band gap

To study the effect of p-doping on energy levels and band gap, three doping potentials were selected from the cyclic voltammogram of P3HT-6, Fig. 8. The potential of 0.00 V was selected to make undoped polymer film because no current was observed at this potential. Hence, no oxidation occurred and holes (vacancies) are not produced. Optical spectrum of undoped polymer film showed an optical band at 505 nm (∼optical band gap = 2.46 eV), Fig. 9A. The partially doped polymer films were made at a potential of 1.00 V. Half of the peak current was observed at this potential. Two broad bands at 491 nm (∼optical band gap = 2.53 eV) and 817 nm (∼optical band gap = 1.52 eV) were observed for partially doped film, Fig. 9B. The band shift is attributed to the partial p-doping of the polymer film. It is assumed that partial doping generated many vacancies (or holes) in HOMO energy level of the conjugated system. Increased holes in HOMO energy level resulted in compressed band gap.41 Several conjugated π-electrons remained at the same energy levels due to only partial doping, therefore, only slight shifting of optical band is observed. However, the broader distribution of optical band can be noticed by the change in the absorption. Highly doped polymer films were made by selecting 1.25 V potential. Highest current was noticed at this potential in the cyclic voltammogram. Optical spectrum of highly doped polymer film exhibit two optical bands at 451 nm (∼optical band gap = 2.75 eV) and 816 nm (∼optical band gap = 1.52 eV), Fig. 9C. High potential led to oxidation of more thiophene rings, hence, a new peak is generated at higher wavelength due to increase in HOMO energy.38 The absorption of broader region of optical spectrum by donor material is advantageous in context of efficiency of OSC. In summary, we tried to evaluate effect of several parameters such as molar mass, regioregularity, and p-doping for improvement of the donor material, P3HT, in context of OSC. Especially important finding of this study is polymerization of 3HT under influence of EEF for improvement of regioregularity of P3HT.

Fig. 9. Optical spectrum and color of (A) undoped P3HT-6 film, (B) partially doped P3HT-6 and (C) highly doped P3HT-6.

4. Conclusion

Efficient donor regioregular P3HT is the fundamental requirement for the better performance of OSC. The synthesis of P3HT by oxidative coupling method suffers from lesser control over molar mass and regioregularity. In this study, we tried to develop protocols for improvement of regioregularity and energy band gap of P3HT synthesized by cost-effective oxidative coupling method. The work is focused on varying different synthetic parameters for better performance of P3HT as donor material of OSC. Initial concentration of monomer has been used to control the molar mass. Narrowly dispersed polymers and higher regioregularity was achieved by polymerization under sonication. Theoretical calculations have shown that energy band gap should decrease with increase of the conjugation length (molar mass) of polymers. The theoretical predictions were endorsed by experimental results. The most important finding of this research is polymerization of 3HT under EEF. This particular aspect has never been addressed before especially for 3HT. The regioregularity of P3HT synthesized under EEF has improved significantly. p-Doping has also proved to be an excellent approach to attain a broader optical band that results in more absorption. New energy states can be created in P3HT by p-doping. The research presented in this study opens new possibilities for improvement in the efficiency of the most widely employed donor material for OSC, P3HT.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declares no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support by Pakistan Science Foundation under scheme Pak-Sri Lanka Joint Projects (Project No. PSF-NSF/Eng/S-HEJ 03) is gratefully acknowledged. Special Thanks to Prof. Dr Shahid Mehmood, chairman, department of physics, University of Karachi for his help in polymerization under high voltage electric field.

References

- Forrest S. R. Nature. 2004;428:911–918. doi: 10.1038/nature02498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidichimo G. Filippelli L. Int. J. Photoenergy. 2010;2010:123534. doi: 10.1155/2010/123534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalowekamo J. Baker E. Sol. Energy. 2009;83:1224–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2009.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Liu M. Zhang Y. Liu Z. Yang Y. Zhao L. Polymers. 2017;9:39. doi: 10.3390/polym9020039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastoor P. C. Nat. Photonics. 2013;7:425–426. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-J. Yang S.-H. Hsu C.-S. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:5868–5923. doi: 10.1021/cr900182s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. Wang K. Gong X. Heeger A. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:4825–4846. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00650C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet J. Kim J. Y. Coates N. E. Ma W. L. Moses D. Heeger A. J. Bazan G. C. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nmat1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc N. Michaud A. Sirois K. Morin J. F. Leclerc M. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006;16:1694–1704. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200600171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon R. Lenes M. Hummelen J. C. Blom P. W. De Boer B. Polym. Rev. 2008;48:531–582. doi: 10.1080/15583720802231833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne A. M. Chen L. Dane J. Hammant T. Braun F. M. Heeney M. Duffy W. McCulloch I. Bradley D. D. Nelson J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:2373–2380. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200800145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schilinsky P. Asawapirom U. Scherf U. Biele M. Brabec C. J. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:2175–2180. doi: 10.1021/cm047811c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trznadel M. Pron A. Zagorska M. Chrzaszcz R. Pielichowski J. Macromolecules. 1998;31:5051–5058. doi: 10.1021/ma970627a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J. L. Lee P. A. Nebesny K. W. Ratcliff E. L. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:19221–19231. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff E. L. Lee P. A. Armstrong N. R. J. Mater. Chem. 2010;20:2672–2679. doi: 10.1039/B923201J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skompska M. Szkurłat A. Electrochim. Acta. 2001;46:4007–4015. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(01)00710-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobade R. S. J. Polym. Eng. 2011;31:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Loewe R. S. Ewbank P. C. Liu J. Zhai L. McCullough R. D. Macromolecules. 2001;34:4324–4333. doi: 10.1021/ma001677+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-A. Wu X. Rieke R. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:233–244. doi: 10.1021/ja00106a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan A. A. Bolm C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2730–2744. doi: 10.1039/B906026J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M. R. Selse D. Berggren M. Järvinen H. Hjertberg T. Inganäs O. Wennerström O. Österholm J.-E. Macromolecules. 1994;27:6503–6506. doi: 10.1021/ma00100a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amou S. Haba O. Shirato K. Hayakawa T. Ueda M. Takeuchi K. Asai M. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1999;37:1943–1948. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0518(19990701)37:13<1943::AID-POLA7>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S. de Visser S. P. Kumar D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11746–11749. doi: 10.1021/ja047432k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir R. Chen H. Lai W. Shaik S. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:301–310. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ise N. Fortschr. Hochpolym.-Forsch. 1969:347–376. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.-Y. Chien W.-C. Ko Y.-H. Chen C.-P. Chang C.-C. Thin Solid Films. 2015;584:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2014.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aragonès A. C. Haworth N. L. Darwish N. Ciampi S. Bloomfield N. J. Wallace G. G. Diez-Perez I. Coote M. L. Nature. 2016;531:88–91. doi: 10.1038/nature16989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dkhissi A. Ouhib F. Chaalane A. Hiorns R. C. Dagron-Lartigau C. Iratcabal P. Desbrieres J. Pouchan C. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:5613–5619. doi: 10.1039/C2CP40170C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan K. Murugan A. V. Marimuthu R. Mulik U. P. Amalnerkar D. P. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1999;61:173–191. doi: 10.1016/S0254-0584(99)00081-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Phys. Rev. Appl. 1988;38:3098. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BecNe A. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.-D. Zheng F. Xu W.-L. Yuan W.-H. Zhu M.-Q. Hao X.-T. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014;47:505502. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/47/50/505502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misra R. Depan D. Challa V. Shah J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:19122–19129. doi: 10.1039/C4CP02089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Cook S. Tuladhar S. M. Choulis S. A. Nelson J. Durrant J. R. Bradley D. D. Giles M. McCulloch I. Ha C.-S. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nmat1574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A. Wijsboom Y. H. Leitus G. Bendikov M. Chem. Mater. 2011;23:896–906. doi: 10.1021/cm102395v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason T. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997;26:443–451. doi: 10.1039/CS9972600443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarella G. Zambianchi M. Di Toro R. Colonna Jr M. Iarossi D. Goldoni F. Bongini A. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:8285–8292. doi: 10.1021/jo960982j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skompska M. Szkurłat A. Electrochim. Acta. 2001;46:4007–4015. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(01)00710-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. Tsai H. Wang H.-L. Cotlet M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:11746–11752. doi: 10.1021/jp105032y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremel K. Ludwigs S. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2014;265:39–82. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45145-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link S. M. Scheuble M. Goll M. Muks E. Ruff A. Hoffmann A. Richter T. V. Lopez Navarrete J. T. Ruiz Delgado M. C. Ludwigs S. Langmuir. 2013;29:15463–15473. doi: 10.1021/la403050c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]