Abstract

Telithromycin (HMR 3647) is the first member of a new family of antimicrobials, the ketolides, developed specifically for the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections. Telithromycin has proven in vitro activity against both common and atypical respiratory tract pathogens. The penetration of telithromycin into bronchopulmonary tissues and subsequent elimination from these sites were evaluated in four groups (groups A, B, C, and D) of six healthy male subjects who received telithromycin at 800 mg once daily for 5 days. Subjects in groups A, B, C, and D underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage 2, 8, 24, and 48 h after receipt of the last dose, respectively. The concentration of telithromycin in the alveolar macrophages, epithelial lining fluid (ELF), and plasma was determined by the agar diffusion method with Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 as the test organism. The concentration of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages markedly exceeded that in plasma, reaching up to 146 times the concentration in plasma 8 h after dosing (median concentration, 81 mg/liter). Telithromycin was retained in alveolar macrophages 24 h after dosing (median concentration, 23 mg/liter), and it was still quantifiable 48 h after dosing (median concentration, 2.15 mg/liter). Telithromycin median concentrations in ELF also markedly exceeded concentrations in plasma (median concentration in ELF, 3.7 mg/liter 8 h after dosing). Telithromycin achieves high and sustained concentrations in ELF and in alveolar macrophages, while it maintains adequate levels in plasma, providing an ideal pharmacokinetic profile for effective treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections caused by either common or atypical, including intracellular, respiratory tract pathogens.

The global spread of antimicrobial resistance among respiratory tract pathogens has created a need for new agents that can demonstrate activity against isolates resistant to existing antimicrobials but that do not readily induce resistance to themselves or exhibit cross-resistance to other agents. Telithromycin (HMR 3647) is the first member of a new family of antimicrobial agents, the ketolides, specifically designed for the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections. Ketolides are a novel addition to the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B group and are specifically characterized by a keto group at position 3 of the macrolactone ring in place of the cladinose moiety present in the macrolides. In vitro induction experiments with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae indicate that it is this novel keto function which accounts for the fact that telithromycin does not induce macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance (3). In addition, a large aromatic N-substituted carbamate extension at position 11 and 12 confers enhanced antimicrobial activity compared with those of the macrolides (8).

In vitro, telithromycin has potent, well-balanced antibacterial activity against all common gram-positive and gram-negative respiratory tract pathogens, irrespective of their susceptibilities to β-lactams and macrolides (1, 16, 17). It is also effective against atypical pathogens such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella spp., and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (2, 19, 21).

In humans, a once-daily oral dose of telithromycin at 800 mg has been shown to provide concentrations in plasma adequate for maintenance of good activity against respiratory tract pathogens, including β-lactam- and macrolide-resistant strains. (B. Lenfant, E. Sultan, C. Wable, M. H. Pascual, B. H. Meyer, and H. E. Scholtz, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-49, 1998). Furthermore, telithromycin concentrates in white blood cells, facilitating delivery of this agent to the site(s) of infection (H. Pham Gia, V. Roeder, F. Namour, E. Sultan, and B. Lenfant, Program abstr. 21st Int. Congr. Chemother., abstr. P79, p. 57, 1999).

The objective of the present study was to determine the pulmonary disposition of telithromycin relative to the concentrations in plasma at steady state and selected times after the cessation of therapy following the oral administration of telithromycin at 800 mg once daily to healthy subjects for 5 days.

(Some of the data presented here have been presented previously in abstract form [C. Muller-Serieys, C. Cantalloube, P. Soler, F. Lemaître, H. Pham Gia, F. Brunner, and A. Andremont, Program abstr. 21st Int. Cong. Chemother., abstr. P 78, p. 57, 1999].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Nonsmoking (for at least 6 months), white, healthy male subjects between the ages of 18 and 40 years and with normal body weights (−15 to +10% according to the Broca formula [normal weight = height, in centimeters, − 100]) were eligible for inclusion in the study. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to screening. Subjects were excluded from the study if they were receiving regular medication or had been exposed to an investigational drug or any drug with a well-defined potential for toxicity to a major organ in the previous 3 months, a macrolide during the previous month, or any other antimicrobial agent within the previous 7 days. Subjects with any condition known to interfere with the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of drugs or who had experienced symptoms of a clinically significant illness in the previous 3 months or any kind of infection within the previous 7 days were also ineligible. Hypersensitivity to local anesthetics was also an exclusion criterion, as lidocaine was used during bronchoscopy.

Study design and procedures.

This was a single-center, open-label study with four parallel groups. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and was carried out in accordance with European Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Each subject received telithromycin at 800 mg once daily (two 400-mg tablets) for 5 consecutive days 15 min after a light breakfast. Subjects were required to drink 500 ml of water during the 3 h after dosing.

The subjects were required to abstain from strenuous physical activity, smoking, and drinking beverages containing alcohol, grapefruit juice, or xanthine derivatives (e.g., coffee or chocolate) from 48 h before initial drug administration until 48 h after receipt of the last dose.

All subjects in groups A, B, C, and D underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at 2, 8, 24, and 48 h after receipt of the last dose of telithromycin, respectively. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed by the same operator, with lidocaine used as a local anesthetic. After routine observation of the respiratory tract, BAL was carried out by infusion of three 50-ml volumes of sterile saline into the subsegmental bronchus of the right middle lobe, and each specimen was immediately aspirated. The first aliquot recovered was discarded and the last two were pooled. The overall BAL procedure was completed in less than 3 min.

Blood samples were collected from all subjects just before dosing on days 1 and 5 and immediately after BAL fluid sampling on day 5 (2 h [group A] or 8 h [group B] after administration of the last dose), day 6 (group C; 24 h after administration of the last dose), or day 7 (group D; 48 h after administration of the last dose).

Sample analysis and handling.

Blood samples were centrifuged (1,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C), and the plasma was stored at −80°C until it was assayed for telithromycin and urea concentrations.

BAL fluid was kept on ice and was centrifuged (400 × g for 10 min at 4°C) to separate the cells from the supernatant, which were then both stored at −80°C until they were assayed. An aliquot of the BAL fluid was retained for determination of the total cell count with a hemocytometer. A differential count of BAL cells was performed with a stained cytocentrifuged sample of BAL fluid to determine the percentage of alveolar macrophages. At least 300 to 500 cells were counted (random-field counting method). It was assumed that all cells in BAL fluid were alveolar macrophages and that the volume of 106 alveolar macrophages was 2.5 μl (6).

To estimate the volume of epithelial lining fluid (ELF) obtained by BAL and to overcome the problem of the unknown dilution factor, introduced by the instillation of saline during the BAL procedure, the urea concentration in plasma and BAL fluid was determined and was used in the following calculation (14): volume of ELF (in milliliters) = (BAL fluid volume [in milliliters] × UBAL)/UP1, where UBAL and UP1 are the urea concentrations (in milligrams per milliliter) in BAL fluid and plasma, respectively.

Urea concentrations in plasma and BAL fluid were measured by a colorimetric enzymatic test (Combination Urea S test [reference no. 7775/10; Boehringer]; assay sensitivity, 0.015 mmol/liter for both plasma and BAL fluid).

Prior to analysis, alveolar macrophage pellets were lysed by sonication and were resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) by shaking in ice for 4 h. The volume of BAL fluid supernatant was measured; the samples were then freeze-dried and resuspended in 3 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) by shaking in ice for 4 h.

Telithromycin assay.

Telithromycin concentrations in ELF, alveolar macrophages, and plasma were determined in triplicate by a validated agar diffusion method with Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 as the test organism. Antibiotic medium 11 (Difco Laboratories) adjusted to pH 9 was used for the plates, which were incubated in air at 35°C. The limit of quantification was 0.03 mg/liter for plasma, ELF, and alveolar macrophages. All samples from the same subject were analyzed in a single batch to minimize assay variability. All samples were analyzed within 3 months of collection.

Spiked samples were included for quality control and to provide a standard curve. Standards for plasma samples were diluted in pooled antibiotic-free human plasma, while standards for ELF and alveolar macrophage samples were diluted in phosphate buffer (pH 8). Standard curves were prepared with telithromycin concentrations ranging between 0.03 and 8 mg/liter. Best-fit standard curves for the telithromycin assays were obtained by linear regression analysis. The intra- and interassay precisions were determined, and the results were considered acceptable when both the inter- and intra-assay differences were less than 20%.

Calculation of telithromycin concentrations in alveolar macrophages, ELF, and BAL fluid.

The concentration of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages (milligram per liter of cells) was calculated from the concentration of telithromycin in the resuspended cell pellet and the total volume of cells. The volume of alveolar macrophage cells was estimated from the following equation: volume of cells (in milliliters) = (total cell number [106 cells]) × (2.5 × 10−3 [in milliliters]). The total cell number was calculated from the concentration of cells in the unconcentrated BAL fluid (in numbers of cells per milliliter) and the BAL fluid volume (in milliliters).

The concentration of telithromycin in ELF was calculated from the following equation: concentration (in milligrams per milliliter) = (telithromycin concentration in BAL/UBAL) × UPl, where UBAL and UPL are the urea concentrations in BAL fluid and plasma, respectively. The concentration of telithromycin in BAL fluid (in milligrams per liter) was calculated from the concentration of telithromycin in the resuspended BAL fluid supernatant divided by the initial volume of BAL fluid.

Safety.

A clinical examination was performed, and standard laboratory parameters (hematology parameters, blood chemistry analysis, and urinalysis) and vital signs (including electrocardiographic findings) were monitored at screening, before the administration of telithromycin on days 1 and 5, and on day 7 (i.e., 48 h after administration of the last dose). Chest X rays were also performed at screening and within 4 h of the fiberoptic bronchoscopy procedure. Adverse events were assessed through questioning and spontaneous reporting from the time that informed consent was given until 15 days after the last dose of telithromycin was taken.

Statistical considerations.

On the basis of previous studies with other antimicrobials, it was estimated that six subjects per group (a total of 24 subjects) would be sufficient to assess the concentrations of telithromycin in target tissues.

Descriptive statistics and statistical analysis were performed with SAS (version 6.11) software. The four groups (groups A, B, C, and D) were compared with respect to the demographic parameters (age, weight, and height) and with respect to the characteristic parameters for BAL fluid (BAL fluid volume, ELF volume, total and differential counts [macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils]) by an analysis of variance after logarithmic transformation of the parameters. The effect of the site sampled (for alveolar macrophages, ELF, and plasma) and the effect of the sampling time (2, 8, 24, and 48 h) on the telithromycin concentration were assessed by analysis of variance after logarithmic transformation of the telithromycin concentration. In the event that the effect was statistically significant, a t test was performed for pairwise comparisons. These analyses were performed with all subjects included in the pharmacokinetic analysis. For all tests performed, a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Demography.

Twenty-four healthy, white males (mean age, 26.8 ± 4.4 years) were recruited and completed the study, with six subjects included in each group. One subject in group A was excluded from the pharmacokinetic analyses because he took only 400 mg instead of 800 mg of telithromycin on days 2 to 4. All other subjects were fully compliant. There were no significant differences among the subjects in groups A, B, C, and D with regard to age, weight, or height (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic parameters for groups A, B, C and Da

| Group | Age (yr) | Wt (kg) | Ht (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 5) | 27.8 (1.6)b | 75.0 (7.1) | 179.2 (4.0) |

| B (n = 6) | 29.7 (4.2) | 82.8 (3.9) | 186.8 (4.3) |

| C (n = 6) | 25.5 (5.4) | 79.4 (12.8) | 182.2 (8.8) |

| D (n = 6) | 23.7 (3.9) | 79.8 (6.1) | 178.3 (4.5) |

P > 0.05 for comparison of demographic parameters among groups.

Values are means (standard deviations).

Recovery of cells from BAL fluid and volumes of BAL fluid and ELF.

The total and differential counts of cells recovered from BAL fluid and the BAL fluid and ELF volumes are given in Table 2. The total cell count, the percentage of each cell type, and the volumes of BAL fluid and ELF were compared among the groups; none were significantly different (P > 0.05). These results are in agreement with data from previous studies performed with healthy subjects (4, 5).

TABLE 2.

Volumes of BAL fluid and ELF and recovery of cells from BAL fluid of groups A, B, C, and D

| Group | BAL vola (ml) | ELF vola (ml) | Total cell counta (106 cells/liter) | Macrophagesa (%) | Lymphocytesa (%) | Neutrophilsa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 5) | 59.5 (8.2)b | 0.85 (0.27) | 154 (118) | 86.1 (10.1) | 11.9 (10.1) | 1.5 (0.7) |

| B (n = 6) | 64.8 (11) | 0.74 (0.19) | 111 (39) | 84.7 (9.3) | 13.7 (8.6) | 1.5 (1.2) |

| C (n = 6) | 64.3 (7.0) | 0.80 (0.24) | 208 (72) | 88.2 (8.3) | 9.6 (7.8) | 1.1 (0.6) |

| D (n = 6) | 53.8 (15.5) | 0.62 (0.33) | 117 (42) | 80.9 (9.6) | 16.7 (9.2) | 2.0 (1.7) |

P > 0.05 for comparison of BAL fluid and ELF volumes and recovery of cells from BAL fluid among groups.

Values are means (standard deviations).

Pharmacokinetic results.

The mean accuracy of the telithromycin assay for plasma quality control samples was between −8 and +3%, and the precision (coefficient of variation) was between 0.9 and 20%. For alveolar macrophage and ELF samples, the accuracy of the telithromycin concentrations was between −10 and +7% and the precision was between 1.2 and 10.9%.

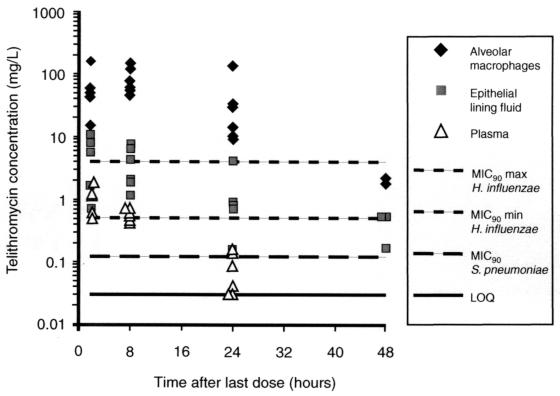

In all subjects, the plasma telithromycin concentration on day 1 before dosing was <0.03 mg/liter. The mean trough concentration measured on day 5 before dosing ranged from 0.018 to 0.093 mg/liter. Telithromycin was detected in both alveolar macrophages and ELF at the first time point: 2 h after dosing on day 5. The median concentrations of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages, ELF, and plasma, together with ratios of the concentration at a specific site to the concentration in plasma, are presented in Table 3. Individual concentrations of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages, ELF, and plasma are plotted in Fig. 1.

TABLE 3.

Concentrations of telithromycin in plasma, alveolar macrophages, and ELF of 23 healthy subjects after administration of telithromycin at 800 mg once daily for 5 days

| Time (h) after last dose | Median (range) concn (mg/liter)

|

Median (range) ratio of the concn in the following to concn in plasma:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMa | ELFb | Plasmac | AM | ELF | |

| 2d(n = 5) | 49 (16–168) | 5.5 (0.7–11.7) | 1.14 (0.53–1.85) | 50 (30–91) | 3.1 (1.1–10.3) |

| 8e(n = 6) | 81 (56–166) | 3.7 (1.2–7.5) | 0.63 (0.42–0.72) | 146 (77–395) | 6.4 (2.0–10.4) |

| 24f(n = 6) | 23 (10–142) | 0.82h (0.15–3.22) | 0.055 (0.03–0.15) | 407 (165–1041) | 12.7b (3.8–27.3) |

| 48g(n = 6) | 2.15i (1.95–2.35) | 0.17j (0.17–0.55) | <0.03 | ||

For pairwise comparisons of telithromycin concentrations in alveolar macrophages (AM), underlined data are not statistically significant (P > 0.05), and italic data are not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

For pairwise comparisons of telithromycin concentrations in ELF, underlined data are not statistically significant (P > 0.05), and italic data are not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

For pairwise comparisons of telithromycin concentrations in plasma, underlined data are not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Within the 2-h group, telithromycin concentrations were as follows: alveolar macrophages > ELF > plasma (P < 0.05).

Within the 8-h group, telithromycin concentrations were as follows: alveolar macrophages > ELF > plasma (P < 0.05).

Within the 24-h group, telithromycin concentrations were as follows: alveolar macrophages > ELF > plasma (P < 0.05).

Within the 48-h group, telithromycin concentrations were as follows: alveolar macrophages > ELF > plasma (P < 0.05).

n = 5.

n = 2.

n = 3.

FIG. 1.

Individual concentrations of telithromycin versus time in alveolar macrophages, ELF, and plasma after administration of telithromycin at 800 mg once daily for 5 days. MIC90, MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited; max, maximum; min, minimum.

The concentrations of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages far exceeded those in plasma (P < 0.05 at each time point). Eight hours after drug administration, the median concentration in alveolar macrophages (81 mg/liter) was 146-fold higher than that in plasma. It was still high 24 h after drug administration (23 mg/liter); 48 h after drug administration, telithromycin was still quantifiable in alveolar macrophages (2.15 mg/liter) in two of six subjects. Telithromycin concentrations in ELF also exceeded those in plasma (P < 0.05 at each time point). The highest median concentration in ELF (5.5 mg/liter) was recorded 2 h after dosing. ELF drug levels were still quantifiable in five of six subjects 24 h after dosing, with a median value of 0.82 mg/liter, and in three of six subjects 48 h after dosing, with a median value of 0.17 mg/liter. The corresponding ratios of the concentration at a specific site:concentration in plasma increased markedly over time in both alveolar macrophages and ELF after the last drug administration.

Safety results.

All 24 subjects were included in the safety analysis. Of these, 11 (46%) subjects reported a total of 17 treatment-related emergent adverse events, usually of mild intensity and involving the gastrointestinal tract (abdominal pain and diarrhea). Alveolar opacity of the right middle lobe was observed on the chest X ray of one subject obtained within 4 h after fiberoptic bronchoscopy. It was reported as an adverse event and was related to the BAL procedure. The chest X ray for this subject was normal a few days later. No severe or serious adverse events were reported. There were no clinically significant changes in electrocardiographic parameters, vital signs, or laboratory safety data except for a transient, unexplained increase in the bilirubin level in one subject which may have been a result of borderline Gilbert's syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Telithromycin is the first clinical candidate of a new family of antimicrobials, the ketolides. Its spectrum of activity covers both common (1, 16, 17) and atypical (2, 19, 21) respiratory tract pathogens. The efficacy of any drug is dependent upon its delivery (i.e., transport and penetration) to the target organ and its stability in situ; a high bronchopulmonary antimicrobial concentration has been shown to be an important predictor of good clinical outcome for respiratory tract infections (12). This study used BAL to determine bronchopulmonary telithromycin concentrations (18), a technique that allows differentiation between ELF and alveolar macrophages and avoids contamination with sputum or saliva.

ELF represents a major site of infection in pneumonia caused by common (extracellular) pathogens (15). In this study, elevated concentrations of telithromycin were sustained in ELF; median telithromycin concentrations in ELF exceeded those in plasma by 6.4-fold at 8 h and were still 0.82 mg/liter 24 h after dosing (which is 12.7-fold higher than those in plasma). Such concentrations are more than adequate to maintain good activity against common respiratory pathogens, including β-lactam- and macrolide-resistant S. pneumoniae and β-lactam-resistant Haemophilus influenzae (C. Agouridas, A. Bonnefoy, and J. F. Chantot, Program abstr. 4th Int. Conf. Macrolides, Azalides, Streptogramins Ketolides, p. 10, 1998); individual concentrations in ELF were above the MIC at which 90% of strains are inhibited for H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae for up to 8 and 24 h, respectively, after administration of the last dose.

Telithromycin was rapidly concentrated by alveolar macrophages, resulting in median intracellular concentrations of up to 81 mg/liter followed by a slow decline over 48 h, ensuring that excellent coverage against intracellular infections was maintained well beyond the cessation of therapy. These findings support the results of an in vitro study, which found that telithromycin was rapidly taken up by human neutrophils with cellular concentration:extracellular concentration ratios of 30 at 5 min and up to 348 at 180 min (22); the rate of efflux of telithromycin from neutrophils into a drug-free medium in this experiment was found to be sufficiently high and the efflux was sufficiently prolonged to suggest good delivery to target tissues in humans. Since alveolar macrophages are the primary reservoir of infection in pneumonia caused by atypical pathogens such as Legionella and Chlamydia spp. (15), telithromycin would be expected to perform well against infections caused by these pathogens. Indeed, telithromycin has shown excellent activity against these organisms both in vitro and in vivo (9, 19, 21) and has been shown to have potent bactericidal activity in a guinea pig model of Legionella pneumophila pneumonia (9).

The persistence of high telithromycin concentration in cells of the lower respiratory tract is also a characteristic of the macrolide antimicrobials, which allows short treatment regimens (13, 15). Previous studies conducted with healthy subjects have demonstrated that clarithromycin and azithromycin concentrate in alveolar macrophages (4, 20).

In addition, telithromycin also reaches high concentrations in plasma. This is critically important in the treatment of respiratory tract infections accompanied by bacteremia, which are associated with a greater risk of mortality (10, 11).

The penetration of telithromycin into ELF and cells is probably a reflection of its amphipathic structure. In contrast, the hydrophilic β-lactams penetrate poorly into tissues, with concentrations reaching only 20 to 40% of the levels in plasma (7).

The data presented here concern noninfected subjects. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that infection would reduce the concentration of telithromycin in alveolar macrophages and ELF. On the contrary, it is anticipated that the combination of increased blood flow, higher capillary permeability, and chemotaxis of white blood cells resulting from inflammation will actually increase the rate of penetration of telithromycin into the lungs.

The sustained penetration of telithromycin in ELF, and particularly into alveolar macrophages, together with its spectrum of activity—covering both common and atypical (intracellular) respiratory pathogens—suggests that telithromycin is a promising new agent for the empiric treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. Antipneumoccal activities of a ketolide (HMR 3647), a streptogramin (quinupristin-dalfopristin), a macrolide (erythromycin), and a lincosamide (clindamycin) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:945–946. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bébéar C M, Renaudin H, Aydin M D, Chantot J F, Bébéar C. In vitro activity of ketolides against mycoplasmas. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:669–670. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnefoy A, Girard A, Agouridas C, Chantot J F. Ketolides lack inducibility properties of MLSB resistance phenotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:85–90. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conte J E, Golden J A, Duncan S, McKenna E, Zurlinden E. Intrapulmonary disposition of clarithromycin and crythromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:334–338. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conte J E, Golden J A, Duncan S, McKenna E, Lin E, Zurlinden E. Single dose intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of azithromycin, clarithromycin, ciproflaxacin, and cefuroxime in volunteer subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1617–1622. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crapo J D, Barry B E, Gehr P, Bachofen M, Weibel E R. Cell numbers and cell characteristics of the normal human lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:332–337. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunha B A. Antibiotic pharmacokinetic considerations in pulmonary infections. Semin Respir Infect. 1991;6:168–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douthwaite S, Hansen L H, Mauvais P. Macrolide-ketolide inhibition of MLS-resistant ribosomes is improved by alternative drug interaction with domain II of 23S rRNA. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:183–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C. In vitro activity of the ketolide HMR 3647 (RU 6647) for Legionella spp., its pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use of the drug to treat guinea pigs with Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:90–95. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch R G, Woodhead M A. Practical considerations and guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia. Drugs. 1998;55:31–45. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine M J, Smith M A, Carson C A, Mutha S S, Sankey S S, Weissfeld L A, Kapoor W N. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275:134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honeybourne D. Antibiotic penetration in the respiratory tract and implications for the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1997;3:170–174. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199703000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lode H. The pharmacokinetics of azithromycin and their clinical significance. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:807–812. doi: 10.1007/BF01975832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller-Serieys C, Bancal C, Dombret M C, Soler P, Murciano G, Aubier M, Bergogne-Berezin E. Penetration of cefpodoxime proxetil in lung parenchyma and epithelial lining fluid of noninfected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2099–2103. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen K M, San Pedro G S, Gann L P, Gubbins P O, Halinski D M, Campbell D. Intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in healthy volunteers given five oral doses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2582–2585. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pankuch G A, Visalli M A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of penicillin-and erythromycin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to HMR 3647 (RU 66647), a new ketolide, compared with susceptibilities to 17 other agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:624–630. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinert R R, Bryskier A, Lutticken R. In vitro activities of the new ketolide antibiotics HMR 3004 and HMR 3647 against Streptococcus pneumoniae in Germany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1509–1511. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retsema J A, Girard A E, Millisen W B. Relationships of high tissue concentrations of azithromycin to bacteriocidal activity and efficacy in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25(Suppl. C):39–44. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R. In vitro activity of a new ketolide antibiotic, HMR 3647, against Chlamydia pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1515–1516. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodvold K A, Gotfried M H, Danziger L H, Servi R J. Intrapulmonary steady-state concentrations of clarithromycin and azithromycin in healthy adult volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1399–1402. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulin T, Wennersten C B, Ferraro M J, Moellering R C, Eliopoulous G M. Susceptibilities of Legionella spp. to newer antimicrobials in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1520–1523. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vazifeh D, Preira A, Bryskier A, Labro M T. Interactions between HMR 3647, a new ketolide and human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1944–1951. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]