Abstract

Mutations in DNA gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV genes are frequently encountered in quinolone-resistant mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. To investigate the mechanism of their effects at the molecular and cellular levels, we have used an Escherichia coli system to overexpress S. pneumoniae gyrase gyrA and topoisomerase IV parC genes encoding respective Ser81Phe and Ser79Phe mutations, two changes widely associated with quinolone resistance. Nickel chelate chromatography yielded highly purified mutant His-tagged proteins that, in the presence of the corresponding GyrB and ParE subunits, reconstituted gyrase and topoisomerase IV complexes with wild-type specific activities. In enzyme inhibition or DNA cleavage assays, these mutant enzyme complexes were at least 8- to 16-fold less responsive to both sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin. The ciprofloxacin-resistant (Cipr) phenotype was silent in a sparfloxacin-resistant (Spxr) S. pneumoniae gyrA (Ser81Phe) strain expressing a demonstrably wild-type topoisomerase IV, whereas Spxr was silent in a Cipr parC (Ser79Phe) strain. These epistatic effects provide strong support for a model in which quinolones kill S. pneumoniae by acting not as enzyme inhibitors but as cellular poisons, with sparfloxacin killing preferentially through gyrase and ciprofloxacin through topoisomerase IV. By immunoblotting using subunit-specific antisera, intracellular GyrA/GyrB levels were a modest threefold higher than those of ParC/ParE, most likely insufficient to allow selective drug action by counterbalancing the 20- to 40-fold preference for cleavable-complex formation through topoisomerase IV observed in vitro. To reconcile these results, we suggest that drug-dependent differences in the efficiency by which ternary complexes are formed, processed, or repaired in S. pneumoniae may be key factors determining the killing pathway.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important human pathogen responsible for respiratory illnesses such as pneumonia and other serious diseases, including meningitis and otitis (4). Concern over the emergence of penicillin-resistant and multidrug-resistant strains has led to the development of antipneumococcal fluoroquinolones, such as sparfloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin. These agents have greater activity than ciprofloxacin against S. pneumoniae, and several are now approved for first-line therapy of community-acquired pneumonia.

The likelihood that increased use of quinolones in the community will result in pneumococci with decreased drug susceptibility has focused attention on the mechanisms of quinolone action and resistance in this organism. Previous studies with Escherichia coli have shown that resistance often involves mutation of DNA gyrase and then of topoisomerase IV (15, 23, 26), two related ATP-dependent enzymes that act by a double-stranded DNA break (29, 46) and collaborate to ensure DNA unwinding during DNA replication and chromosome segregation at cell division (1, 49). Quinolones are thought to form a topoisomerase-drug-DNA ternary complex (10, 11, 14) that cellular processes convert into a lethal lesion, possibly a double-stranded DNA break (18, 44). Resistance mutations occur in a short discrete segment of the DNA gyrase gyrA and gyrB genes (and analogous parts of the topoisomerase IV parC and parE genes) termed the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) (7, 33, 35, 47, 48). Hot spots for resistance involve changes of S. pneumoniae GyrA Ser81 to Phe or Tyr and of ParC Ser79 to Phe or Tyr (16, 17, 22, 32, 36–39, 41, 45). The precise effects of these changes remain to be examined at the enzyme level.

Attempts to understand the target preferences of quinolones in S. pneumoniae have centered on identifying the order of QRDR mutations acquired during stepwise drug challenge. Surprisingly, we found that ciprofloxacin selected parC (Ser79Phe or Tyr) QRDR changes (16, 22, 32, 36), whereas sparfloxacin selected gyrA (Ser81Phe or Tyr) QRDR mutants (38). We therefore proposed that the structure of the quinolone determines its target preference in S. pneumoniae (38). However, subsequent work showing that other quinolones, such as norfloxacin, levofloxacin, pefloxacin, and trovafloxacin, select parC changes (13, 41, 45) and the finding that S. pneumoniae topoisomerase IV is more sensitive than gyrase to inhibition by quinolones (including sparfloxacin) (31, 40) led Morrissey and George to suggest that topoisomerase IV is the quinolone target in S. pneumoniae (31) as in Staphylococcus aureus (8, 9, 34). Non-QRDR topoisomerase IV resistance mutations were invoked by them to explain the sparfloxacin resistance of our first-step gyrA mutants (31).

Though sparfloxacin is not alone in selecting gyrA mutants (2, 17, 39, 42), we have sought to clarify the roles of gyrase and topoisomerase IV in drug action. Here we exclude the participation of non-QRDR mutations in sparfloxacin resistance and, by characterizing recombinant Ser81Phe GyrA and Ser79Phe ParC proteins expressed in E. coli, establish that both mutations confer resistance to sparfloxacin (Spxr) and to ciprofloxacin (Cipr) in assays of enzyme inhibition and cleavable-complex formation. That the Cipr phenotype of the corresponding gyrA allele and the Spxr phenotype of the parC allele are silent in the wild-type S. pneumoniae background supports our proposed model that different quinolones act as cellular poisons through different topoisomerase targets. From these results and immunoblotting analysis of topoisomerase expression levels, we discuss the mechanism of selective quinolone action in S. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and reagents.

Luria broth and Luria agar were prepared as described previously (43), as was brain heart infusion medium containing 10% horse blood (37). Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride and sparfloxacin hydrochloride were kindly provided by Bayer UK, Newbury, United Kingdom, and by Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Suita, Japan.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

S. pneumoniae strain 7785 and its mutants 1C1, 1S1, 1S4, 2C6, 2C7, 2S1, 2GM1, and 3C4 have been described elsewhere (17, 36–38). S. pneumoniae R6 is a standard laboratory strain. E. coli strain DH5α, used for cloning purposes, and strains BL21(λDE3)pLysS and BL21(λDE3)pLysE, used for protein expression, were from our laboratory collection. Plasmids pXP9, pXP10, pXP13, and pXP14, used to express S. pneumoniae GyrB, GyrA, ParC, and ParE proteins, have been described previously (40). Supercoiled and relaxed plasmid pBR322 DNAs were prepared as described earlier (40).

Drug susceptibilities.

A twofold-dilution method was employed in which ∼105 CFU of bacteria was spotted on brain heart infusion-agar plates which were read after overnight aerobic incubation at 37°C. The MIC is the drug concentration at which no bacterial growth was seen under these conditions.

DNA sequence analysis.

PCR was used to amplify the parE-parC region of strains 1S1 and 1S4. For each strain, three overlapping fragments were obtained that spanned 5.5 kb and included the entire parE and parC genes, the 400-bp intergenic region, and a sequence of about 300 bp upstream of the parE gene carrying the promoter region. The following primer pairs were used (37): H4023, 5′-GTCAATCACAAAGGTTG (nucleotide [nt] positions −316 to −300 upstream of parE); and reverse primer M0361, 5′-TCCGACTCTAATTTCC (nt positions 44 to 28 bp downstream of the parE termination codon); N6894, 5′-TGGGCTTTGTATCATATGTCTAAC (nt positions −15 to +9 at the start of the parC gene; underlining indicates an NdeI site overlapping the initiation codon); and reverse primer N6893, 5′-TGGCATCAAGAGATGGTC (nt positions 406 to 389 downstream of the parC termination codon); and finally, G8394, 5′-TGAAGCGATTGAGTTCC (nt positions 650 to 666 in the parE gene); and reverse primer M4721, 5′-TGCTGGCAAGACCGTTGG (nt positions 470 to 453 of the parC gene). Genomic DNA was prepared from strains 1S1 and 1S4 as previously described (38) and was used as the template for Taq DNA polymerase in the presence of 1.5 mM MgCl2. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and polymerization at 72°C for 3 min. Reactions were performed over 30 cycles. PCR products corresponding to the 2.3-kb parE fragment, 2.9-kb parC fragment, and 2.2-kb linking region were obtained and were each purified on Qiagen minispin columns. The DNA was sequenced directly on both top and bottom strands using an ABI Prism automated sequencer and a series of nested oligonucleotide primers.

GyrA(Phe81) and ParC(Phe79) expression plasmids.

An overexpression construct containing the mutant gyrA gene was obtained by fragment exchange into gyrA plasmid pXP10 (40). PCR was used to amplify a 528-bp fragment corresponding to the 5′end of gyrA using chromosomal DNA from strain 1S1 as the template. The primers used were VGA35, 5′-ATGAGGCATTTACATATGCAGGATAAAAATTTAGTG (an NdeI site overlapping the ATG initiation codon is underlined) (40); and reverse primer VGA4, 5′-AGTTGCTCCATTAACCA (36). Strain 1S1 DNA and primers were incubated with Vent DNA polymerase (which has proofreading activity) in the presence of 1.5 mM MgCl2 under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 48°C for 1 min, and polymerization at 72°C for 3 min. Reactions were performed over 30 cycles. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and with EcoRV (at an internal site in gyrA), purified by electrophoresis in low-gelling agarose, and recovered. The 405-bp fragment was ligated into NdeI-EcoRV-digested plasmid pXP10 and was used to transform E. coli DH5α. Several fragment exchange plasmids were recovered, and following restriction analysis, the gyrA gene of one, pXP15, was sequenced in its entirety to confirm that the gyrA gene had the correct reading frame and encoded the Ser81Phe mutation.

An overexpressing clone for ParC(Phe79) was constructed similarly. A 485-bp PCR product (nt −15 to +470) encoding the N-terminal region of ParC(Phe79) was amplified using primers N6894 and M4721 (see above), Vent polymerase, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and chromosomal DNA from S. pneumoniae mutant 2C7 as the template. PCR conditions were as above for the mutant gyrA fragment. After digestion with NdeI and EcoRV, the 400-bp fragment was exchanged into NdeI-EcoRV-cut parC expression vector pXP14 (40), yielding plasmid pXP16.

Purification of gyrase and topoisomerase IV subunits and generation of antibodies.

Conditions for the overexpression of recombinant S. pneumoniae GyrB, GyrA, ParC, and ParE subunits as His-tagged proteins in E. coli BL21 and detailed protocols for their purification to >95% homogeneity by nickel chelate column chromatography have been published elsewhere (40). These proteins were used individually as antigens to immunize rabbits and as ligands (absorbed to nitrocellulose) for affinity purification of rabbit antibodies. Mutant GyrA and ParC proteins were produced in E. coli BL21(λDE3) by induction of plasmids pXP15 and pXP16 and were purified as described for the wild-type subunits (40).

Immunodetection and quantitation of gyrase and topoisomerase IV proteins in S. pneumoniae cell lysates.

S. pneumoniae strains were grown overnight at 37°C either on brain heart infusion plates containing 10% horse blood or alternatively in Todd-Hewitt liquid medium in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Approximately 5 × 109 CFU could be collected from confluent growth on three 90-mm-diameter petri dishes or from 10 ml of liquid medium. For cell lysis, 5 × 109 cells were collected, washed once with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, and then resuspended in 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and Complete protease inhibitor (Boehringer) (one tablet was dissolved in 1 ml of water, and 20 μl was added). The suspension was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and then 500 μl of 2× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample loading buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% [wt/vol] glycerol, 1.43 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.2% bromophenol blue) was added, and the mixture was left at room temperature for 10 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 100,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C in a Beckman TL-100 ultracentrifuge. The supernatant was used in SDS-PAGE analysis.

Quantitation of topoisomerase proteins in cell lysates was done by Western blotting as follows. Proteins in crude extracts were quantitated by the Bradford method. Equal amounts of protein extracts were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE on 6% polyacrylamide gels. Purified gyrase or topoisomerase IV protein standards (each at 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, or 60 ng) were run alongside. Proteins were transferred to Nitrocellulose Extra Blotting Membrane using a Sartoblot II apparatus (Sartorius). The membrane was incubated with blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 500 mM NaCl) for 1 h at room temperature followed by the addition of appropriately diluted rabbit anti-GyrA, -GyrB, -ParC, or -ParE antiserum (1 in 200 to 1 in 2,000) in 10 ml of fresh blocking solution. After incubation for 2 h at room temperature, the membrane was washed three or four times with TS solution (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 500 mM NaCl) over a period of 15 min. The second antibody—either alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma) diluted 1 in 2,000 or fluorescein-linked donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham) diluted 1 in 30—was added in fresh blocking solution, and the membrane was incubated for a further 2 h. The membranes were washed, and alkaline phosphatase conjugates were visualized by nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) color development (3) and were quantified using an Image Station 440 instrument (Kodak Digital Science). Fluorescein-linked antibody complexes were quantitated by fluorescence using a Molecular Dynamics Storm analyzer and ImageQuant software.

DNA supercoiling, kDNA decatenation, and DNA cleavage assays.

Conditions for reconstitution of S. pneumoniae gyrase and topoisomerase IV from their subunits and assaying of supercoiling and kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) decatenation activity in the absence or presence of quinolone inhibitors have been described previously (40). The efficiency of wild-type and mutant gyrase complexes in mediating quinolone-promoted DNA breakage was determined as described earlier (40). The extent of DNA cleavage was quantitated from photographic negatives using a Molecular Dynamics Personal Densitometer SI and ImageQuant software.

RESULTS

Construction of Phe81 GyrA and Phe79 ParC expression plasmids and purification of His-tagged proteins.

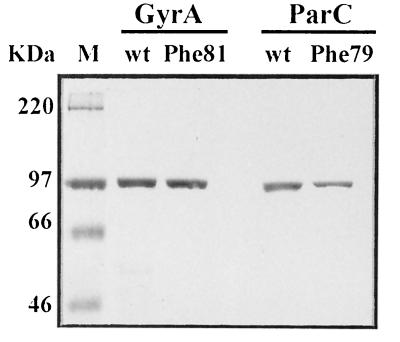

To obtain the mutant proteins in quantity, we used a fragment exchange procedure to introduce the relevant mutation into gyrA expression plasmid pXP10 or parC plasmid pXP14, yielding constructs pXP15 and pXP16 (see Materials and Methods). The mutant gyrA and parC fragments were produced by PCR using proofreading Vent polymerase and chromosomal DNA from strains 1S1 and 2C7 as template (Table 1). The mutant gyrA and parC genes in pXP15 and pXP16 were sequenced in full to ensure that they differed from the 7785 parent sequence only at the expected codon. Transformation of the four plasmids into E. coli allowed isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-inducible expression of wild-type and mutant subunits as His-tagged proteins (40). After nickel chelate column chromatography, all four proteins were obtained in soluble form at >95% homogeneity (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Quinolone resistance phenotypes of S. pneumoniae mutants

| Straina | Mutationb in the QRDR of:

|

(MIC) (μg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA | ParC | Sparfloxacin | Ciprofloxacin | |

| 7785 | — | — | 0.25 | 1 |

| 1S1 | Ser81Phe | — | 2 | 1 |

| 1S4 | Ser81Tyr | — | 2 | 1 |

| 1C1 | — | — | 0.25 | 3 |

| 2C6 | — | Ser79Tyr | 0.25 | 8 |

| 2C7 | — | Ser79Phe | 0.25 | 8 |

| 2S1 | Ser81Phe | Ser79Tyr | 32 | 64 |

| 2GM1 | Ser81Phe | Ser79Phe | 32 | 64 |

| 3C4 | Ser81Tyr | Ser79Tyr | 32 | 64 |

Strains were derived by stepwise drug challenge from parent 7785 (17, 36–38). 1S1 and 1S4 were first-step Spxr mutants of 7785. 1S1 was the parent of second-step mutant 2S1. Strain 1C1 was a first-step efflux mutant selected from 7785 with ciprofloxacin (17, 36) and was the parent of second-step mutants 2C6 and 2C7. 1C1 retains susceptibility to sparfloxacin (38). None of the strains harbored QRDR mutations in gyrB or parE.

—, wild-type QRDR sequence.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of highly purified S. pneumoniae wild-type (wt) GyrA, GyrA(Phe81), wild-type ParC, and ParC(Phe79) proteins. The His-tagged proteins were overexpressed in E. coli, purified by nickel resin chromatography, and examined on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel. Lane M, marker proteins (sizes in kilodaltons).

Mutant gyrase and topoisomerase IV complexes are catalytically efficient and resistant to quinolone inhibition.

When complemented with recombinant S. pneumoniae GyrB, the specific activity of Phe81 GyrA in a supercoiling assay was 2 × 105 U/mg, which is comparable to that of the wild type (40). The specific activity of the Phe79 ParC protein when complemented with recombinant ParE in a kDNA decatenation assay was 2.5 × 105 U/mg, which is also similar to that of wild-type ParC (40). It seems that neither mutation impairs catalytic activity.

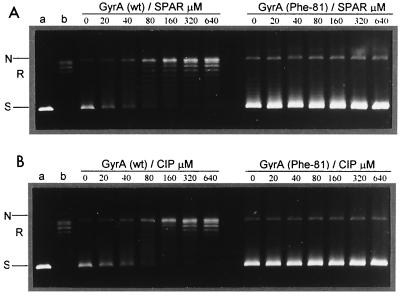

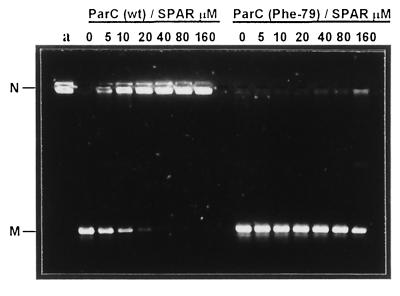

Figure 2 shows that ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin were comparably effective inhibitors of ATP-dependent DNA supercoiling by gyrase with 50% inhibitory concentrations of 20 to 40 μM, confirming previous studies (40). However, for the mutant gyrase, either drug at concentrations up to 640 μM had little or no inhibitory effect; the DNA was fully supercoiled by the enzyme (Fig. 2A and B). Figure 3 compares the inhibition of topoisomerase IV activity. The 50% inhibitory concentrations for sparfloxacin inhibition of wild-type and mutant complexes were 10 and >160 μM, respectively. Similar results were seen for ciprofloxacin (not shown). Thus, the respective Ser81Phe and Ser79Phe mutations in GyrA and ParC reduced enzyme inhibition by a factor of >16-fold for both sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin.

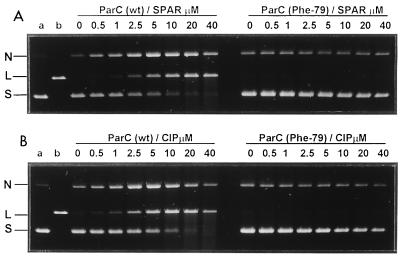

FIG. 2.

DNA supercoiling activity of mutant S. pneumoniae DNA gyrase is highly refractory to inhibition by sparfloxacin (SPAR) (A) and by ciprofloxacin (CIP) (B). Relaxed pBR322 (0.4 μg) was incubated with gyrase activity (1 U) reconstituted from GyrB and either wild-type (wt) GyrA (left lanes) or GyrA(Phe81) (right lanes) in the presence of 1.4 mM ATP and the indicated amounts (in micromolar) of quinolones. Reactions were stopped, and the DNA products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. DNA was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV illumination. Lanes a and b, supercoiled and relaxed pBR322 DNA, respectively. N, R, and S denote nicked, relaxed, and supercoiled DNA, respectively.

FIG. 3.

S. pneumoniae topoisomerase IV containing the ParC(Phe79) subunit is resistant to inhibition by sparfloxacin (SPAR). Topoisomerase IV activity (1 U), reconstituted from recombinant ParE subunit and either wild-type (wt) ParC or ParC(Phe79) protein, was incubated with kDNA (0.4 μg) in the presence of 1.4 mM ATP and quinolones at the concentrations indicated. DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described in Fig. 2. Lane a, kDNA. N and M indicate kinetoplast network DNA and released relaxed minicircles, respectively.

Mutations markedly impede cleavable-complex formation with sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin.

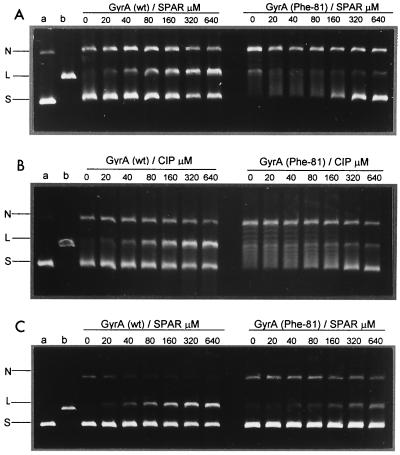

To examine effects on cleavable-complex formation, supercoiled pBR322 was incubated with equal amounts of wild-type or mutant topoisomerases in the absence or presence of quinolones. After addition of SDS to induce DNA cleavage, samples were treated with proteinase K to remove GyrA (ParC) protein covalently linked to DNA. The products were then analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. Drug stabilization of the cleavable complex is expected to generate linear DNA on denaturation. For wild-type gyrase (Fig. 4), inclusion of ciprofloxacin or sparfloxacin produced a dose-dependent increase in linear DNA product, with values of 80 μM for the drug concentration producing 25% conversion of input DNA to the linear form. Unlike wild-type enzyme, the mutant gyrase exhibited a low level of DNA cleavage activity that was not further stimulated by drugs even at 640 μM. Moreover, although the wild-type enzyme showed weak DNA-relaxing activity, this activity was more marked with the mutant enzyme (Fig. 4, right panels). Inclusion of 1.4 mM ATP blocked DNA relaxation and produced a small (twofold) stimulation of sparfloxacin-mediated DNA breakage by both the wild-type and mutant enzymes, increasing DNA breakage by the mutant enzyme to 10% of total DNA at 640 μM sparfloxacin (Fig. 4C). Similar results were seen for ciprofloxacin (not shown). Thus, the mutant gyrase complex was at least 8- to 16-fold less efficient in cleavable-complex formation.

FIG. 4.

Ser81Phe mutation in GyrA impairs DNA cleavage by gyrase promoted by sparfloxacin (SPAR) (A and C) or ciprofloxacin (B). Supercoiled pBR322 DNA (0.4 μg) was incubated with S. pneumoniae GyrB (1.7 μg) and either wild-type (wt) GyrA or GyrA(Phe81) (0.45 μg) in the absence (A and B) or presence of 1.4 mM ATP (C) and quinolones at the concentrations indicated. After addition of SDS and proteinase K, DNA samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. Lanes a and b, supercoiled pBR322 and EcoRI-cut pBR322. N, L, and S indicate nicked, linear, and supercoiled DNA.

For wild-type topoisomerase IV, drug-dependent cleavage of DNA was much more efficient than with gyrase, yielding values for both sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin of 2.5 to 5 μM for the drug concentration producing 25% conversion of input DNA to the linear form and evidence of multiple cleavage of the DNA at drug concentrations of >10 μM (Fig. 5). Thus, topoisomerase IV is some 20- to 40-fold more efficient than gyrase in DNA breakage (31, 40). For the mutant enzyme, no DNA cleavage was observed even using 40 μM sparfloxacin or ciprofloxacin (Fig. 5). Inclusion of ATP had only a modest effect on DNA cleavage (not shown). The mutant topoisomerase IV was therefore some 40-fold more resistant to trapping by the two quinolones, a result similar to that observed for the Phe81 change in GyrA (Fig. 4). These biochemical data establish the key result that the Ser81Phe GyrA and Ser79Phe ParC mutations confer resistance in vitro to both sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin.

FIG. 5.

DNA breakage by topoisomerase IV mediated by sparfloxacin (SPAR) (A) and by ciprofloxacin (B) is inhibited by the Phe79 mutation in ParC. DNA cleavage reactions were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 4 using ParE (1.7 μg) and wild-type (wt) ParC or ParC(Phe79) (0.45 μg) but with a lower range of quinolone concentrations.

Cipr phenotype of the gyrA(Ser81Phe) allele and Spxr phenotype of parC(Ser79Phe) are silent in S. pneumoniae: evidence for target selection and a poison mechanism.

The enzyme results can be compared with the resistance profiles of S. pneumoniae strains expressing the same mutant alleles (Table 1). Strain 1S1 is a first-step mutant selected with sparfloxacin which expresses Ser81Phe GyrA. From the in vitro enzyme studies, it appears that this mutation alone would be sufficient to account for the eightfold increase in resistance to sparfloxacin (Table 1). Interestingly, in contrast to expectations from enzyme studies, strain 1S1 was susceptible to ciprofloxacin. A second independent, first-step, sparfloxacin-selected mutant, 1S4, expressing Ser81Tyr GyrA, behaved similarly (Table 1). The silent Cipr phenotype of these gyrA alleles can be explained if ciprofloxacin acts selectively through topoisomerase IV, not through gyrase. Similarly, strain 2C7 selected with ciprofloxacin and expressing the parC(Ser79Phe) allele exhibited the expected resistance to ciprofloxacin but, contrary to the enzyme studies, was susceptible to sparfloxacin (Table 1). Mutant 2C6 carrying a Ser79Tyr alteration showed similar behavior. The silent Spxr phenotype of the parC allele would be expected if sparfloxacin acted preferentially through gyrase, consistent with results for strain 1S1. We note that the presence of mutations in both parC and gyrA in strains 2S1, 2GM1, and 3C4 generated a Cipr Spxr phenotype (Table 1). Taken together, the data in Table 1 show that the Cipr phenotype of a mutant gyrA gene is masked by a wild-type parC gene, whereas the Spxr phenotype of the mutant parC gene is masked by a wild-type gyrA gene. These epistatic effects of the gyrA and parC genes are not consistent with a killing mechanism involving simple enzyme inhibition but suggest that the quinolones act by a poison mechanism involving selective trapping of gyrase or topoisomerase IV as cleavable complexes (27).

Spxr gyrA strains carry wild-type parE-parC genes: topoisomerase IV is not the preferred intracellular target of the drug.

It has been suggested that topoisomerase IV is the intracellular target of all quinolones, including sparfloxacin (31). To explain the selection by sparfloxacin of first-step gyrA mutants such as 1S1 and 1S4 (Table 1), it was proposed by others that these strains must be double mutants carrying an additional undetected non-QRDR resistance mutation in topoisomerase IV (31). It was important to test this idea, as recent work on clinafloxacin resistance has suggested that some S. pneumoniae QRDRs may be more extensive than those defined in E. coli (39). Moreover, resistance to premafloxacin in S. aureus involves parC mutations that lie outside the conventional QRDR (20). Therefore, we amplified the entire 5.5-kb parE-parC locus of independent strains 1S1 and 1S4 in each case as three overlapping PCR products comprising a sequence 300 bp upstream of the parE gene to 300 bp downstream of parC. Direct sequence analysis of the PCR products revealed no differences in the parE and parC genes or their promoters in 1S1 or 1S4, compared to the known sequences of parental strain 7785. The absence of topoisomerase IV mutations in these strains indicates that sparfloxacin resistance accrues from a mutation at GyrA Ser81 and that gyrase (not topoisomerase IV) is the intracellular target.

Gyrase and topoisomerase IV subunits are differentially expressed in S. pneumoniae: relevance for ternary-complex formation.

The relative amounts of ternary-complex formation will depend not only on drug-enzyme affinities but also on intracellular enzyme levels. To determine whether the apparently overwhelming in vitro preference of quinolones for topoisomerase IV might be counterbalanced by differential expression of gyrase in vivo, we developed and applied a quantitative immunoblotting procedure using rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against highly purified S. pneumoniae GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE subunits produced in E. coli (40). Given the sequence homology between the 97-kDa GyrA and ParC proteins and between the 72-kDa GyrB and ParE subunits, cross-reacting antibodies were first removed from each antiserum by employing the purified recombinant proteins as ligands absorbed to nitrocellulose. By using quantitative immunoblotting with the recombinant subunits as standards, it was found that the anti-GyrA and anti-ParC antibodies were specific and did not cross-react with ParC and GyrA proteins, respectively (Fig. 6, panels 1 to 3). Similarly, the anti-GyrB and anti-ParE antisera were also specific (Fig. 6, panels 4 to 6). It was possible to detect 10 ng of each topoisomerase protein.

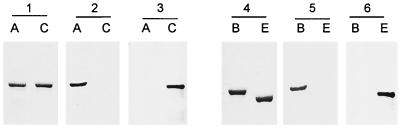

FIG. 6.

Polyclonal antisera specific for the S. pneumoniae GyrA, ParC, GyrB, and ParE proteins. Equimolar amounts of highly purified recombinant GyrA (A), ParC (C), GyrB (B), and ParE (E) proteins were run on SDS–6% polyacrylamide gels which were either stained with Coomassie blue (panels 1 and 4) or electrotransferred to nitrocellulose filters (panels 2, 3, 5, and 6). The filters were probed with rabbit antisera made to the recombinant His-tagged GyrA (panel 2) and ParC (panel 3) or recombinant His-tagged GyrB (panel 5) or ParE subunit (panel 6). In each case, GyrA- and ParC- and GyrB- and ParE- antisera were prestripped of cross-reacting antibodies using the other homologous recombinant protein as an affinity ligand. The binding of the first antibody was visualized by using an alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG second antibody with colorimetric development.

Western blot analysis was used to examine topoisomerase subunit levels in SDS lysates of wild-type S. pneumoniae strains 7785 and R6 grown on brain heart infusion-blood agar plates. Lysates from either strain gave similar results that were obtained reproducibly in several independent experiments. Figure 7A shows a representative experiment in which known amounts of the recombinant GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE proteins were used for quantitation purposes. By use of 4 μg of protein extract, the GyrA and GyrB proteins were readily detected at ∼40- and ∼20-ng levels, respectively. By contrast, the ParC and ParE protein bands were barely visible (Fig. 7A). To detect ParC and ParE proteins, it was necessary to increase the amount of the protein extract loaded on the gel. By loading, respectively, 16- and 32-μg total proteins, ParC and ParE bands could then each be reliably detected at the 40-ng level (Fig. 7B). Thus, the ParC and ParE proteins were present at approximately fourfold-lower levels than their GyrA and GyrB counterparts.

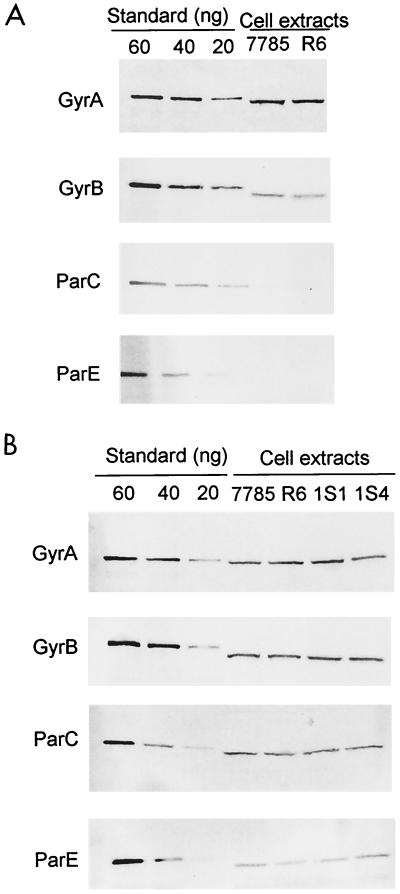

FIG. 7.

Quantitative immunoblotting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV subunits in protein lysates of S. pneumoniae and its quinolone-resistant mutants. (A) GyrA and GyrB are more abundant in cell extracts than ParC and ParE. Protein extracts (4 μg) from wild-type S. pneumoniae strains 7785 and R6 prepared by SDS lysis were run on four SDS–6% polyacrylamide gels alongside known amounts of recombinant GyrA, GyrB, ParC, or ParE protein used as the standard. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and probed with specific antisera and a second antibody as described in the Fig. 6 legend. Due to the presence of histidine tags, the protein standards have a slightly lower mobility than the native proteins. (B) ParC and ParE proteins are detected using four- to eightfold higher amounts of extract. Protein extracts, prepared from strains 7785 and R6 and gyrA mutants 1S1 and 1S4, were loaded at 4 μg per lane for detection of GyrA and GyrB and at 16 μg and 32 μg per lane for quantitation of ParC and ParE, respectively.

To quantitate more accurately the predominance of gyrase over topoisomerase IV, blots were also probed using a second antibody conjugated to fluorescein rather than to alkaline phosphatase, allowing fluorescence detection against 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 ng of recombinant protein standards. Gyrase subunits were present at threefold-greater (±0.2) molar levels than those of topoisomerase IV in S. pneumoniae extracts (not shown). Similar results were obtained for log-phase growth of strains 7785 and R6 in Todd-Hewitt liquid medium (data not shown). Moreover, though all the extracts shown in Fig. 7 were prepared in the presence of a cocktail of protease inhibitors, the same results were seen when these inhibitors were omitted (not shown). The reproducibility of results for two S. pneumoniae strains using different growth and lysis conditions suggests that the threefold-greater level of gyrase subunits than of topoisomerase IV is unlikely to be a proteolytic artifact but derives from differential cellular expression. Interestingly, the relative amounts of GyrA to GyrB in strains 7785 and R6 were in each case 1.7 ± 0.2, which, allowing for molecular-weight differences, indicates that the subunits are present in equimolar ratios. The same was seen for ParC and ParE. From the number of bacteria used in these experiments, we calculate that GyrA and GyrB are both present at approximately 4,000 copies per cell. Overall, it appears that gyrase levels are only modestly higher than those of topoisomerase IV in S. pneumoniae.

Effects of gyrA resistance mutations on topoisomerase expression levels.

The countervailing activities of gyrase and of relaxing enzymes such as topoisomerase IV are important in maintaining chromosomal supercoiling (28, 50). Moreover, the expression of some genes, including gyrase, is homeostatically regulated by DNA supercoiling. To determine whether gyrase mutations contribute to quinolone resistance by downregulating the expression of gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV subunits, we examined protein extracts from strains 1S1 and 1S4 by immunoblotting (Fig. 7B). In both cases, it is clear that the GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE levels in the mutants were not visibly different from those present in wild-type strains 7785 and R6. Thus, the Ser81Phe or -Tyr mutations in GyrA do not cause resistance indirectly by affecting topoisomerase expression in S. pneumoniae but interfere directly with ternary-complex formation.

DISCUSSION

We have applied a combination of biochemical and immunochemical approaches to analyze the properties of both wild-type S. pneumoniae GyrA and ParC proteins and mutants bearing respective Ser81Phe and Ser79Phe mutations, changes that are frequently observed in quinolone-resistant strains. By reconstitution of the mutant proteins with the complementary GyrB and ParE subunits, we have shown for the first time that the resulting gyrase and topoisomerase IV complexes were each at least some 8- to 16-fold less efficient in forming cleavable complexes (the relevant lesion) with quinolones. These biochemical studies establish the important result that the two mutations both confer resistance to both sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin. That the Cipr phenotype was silent in an Spxr S. pneumoniae gyrA(Ser81Phe) strain expressing a wild-type topoisomerase IV, whereas Spxr was silent in a Cipr parC(Ser79Phe) strain, shows that sparfloxacin acts preferentially through gyrase, whereas ciprofloxacin acts through topoisomerase IV. The enzyme and genetic data therefore provide direct support for an earlier proposal that these quinolones act selectively through different targets in S. pneumoniae (38).

Recent transformation studies complement work on first-step resistant mutants in confirming the resistance phenotypes of mutant GyrA and ParC proteins in S. pneumoniae. Thus, defined parC PCR products encoding the Ser79Phe mutation have been shown to transform wild-type S. pneumoniae to ciprofloxacin resistance (32). Unfortunately, the sparfloxacin response of the transformants was not tested. Very recently, gyrA PCR fragments encoding the Ser81Phe alteration yielded transformants that were Spxr but Cips (21). These results are in agreement with studies of first-step gyrA mutants (Table 1) and can be attributed directly to the Ser81Phe mutation. Thus, transformation, mutant characterization, and enzyme studies concur in providing unequivocal evidence for selective quinolone targeting.

The key to the enzyme studies has been the development of a reliable E. coli expression system for the S. pneumoniae gyrase and topoisomerase IV subunits using plasmid-borne genes whose sequence has been completely determined. By using a fragment exchange protocol, it was possible to introduce a single, validated codon change into the wild-type gyrA or parC gene used for protein expression. The reconstituted gyrase and topoisomerase IV complexes therefore differ from the wild type by a single amino acid change. The Ser81Phe mutation in GyrA and the Ser79Phe change in ParC lie at equivalent positions in the two proteins. Ser81 in S. pneumoniae GyrA is equivalent to Ser83 in the E. coli protein (7, 35), which X-ray structure analysis has shown lies in helix A'α4, part of a helix-loop-helix motif thought to contact DNA and form the quinolone binding site (30). Presumably, mutation of Ser81 to Phe in the S. pneumoniae GyrA protein (or Ser79 in ParC) confers resistance by interfering with quinolone binding, thereby preventing assembly of the ternary complex. Consistent with this idea, we note that dose-dependent DNA cleavage was detected with the mutant enzymes (in the presence of ATP) at very high drug concentrations (e.g., Fig. 4C) suggesting that the two mutations operate by reducing drug affinity for the target. It is not known whether this effect is due to the steric bulk of the phenylalanine side chain, greater than that of serine (7).

Several interesting points emerge from the drug inhibition studies of the wild-type and quinolone-resistant topoisomerase complexes. First, topoisomerase IV is some 20- to 40-fold more efficient than gyrase in forming cleavable complexes with quinolones (Fig. 4 and 5). Second, despite their structural differences, the in vitro enzyme inhibitory properties of sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin are very similar. These two features are difficult to reconcile with the clear in vivo evidence that sparfloxacin acts through gyrase and ciprofloxacin through topoisomerase IV. Obviously, if the strong predilection for quinolone action on topoisomerase IV holds under cellular conditions, then some other feature(s) must override drug-enzyme affinities so that sparfloxacin can kill through gyrase. In considering this point, we reasoned that ternary-complex formation favoring topoisomerase IV might be counterbalanced by differences in intracellular topoisomerase expression favoring gyrase. Small differences between quinolone target affinities affected by ATP, salt, DNA sequence, or chromosomal supercoiling might then allow selective killing through one or another target. However, by immunoblotting, it was found that gyrase levels are only three times higher than those of topoisomerase IV in S. pneumoniae cell extracts (Fig. 7), a ratio similar to that reported recently for Bacillus subtilis (19). It seems unlikely that these modest differences in expression alone could overturn the 20- to 40-fold preference for cleavable-complex formation with topoisomerase IV and allow selective drug action. Unfortunately, our attempts to examine cleavable-complex formation in S. pneumoniae have thus far been obfuscated by the relatively low levels of DNA breakage that can be induced in vivo (data not shown).

To account for selective intracellular drug targeting, we propose that there are drug-dependent differences in ternary-complex formation, processing, or repair in S. pneumoniae. This hypothesis requires that the ternary complexes formed by sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin in vivo are somehow different from those formed in vitro, as no differences were seen in drug effects on the purified enzymes (Fig. 2 to 5). We note that quinolones are thought to act by forming ternary complexes upstream of the replication fork such that collisions between a component of the replication machinery, e.g., DNA polymerase or DNA helicase, and subsequent processing, e.g., abortive repair, convert the complex into an irreversible lethal lesion (24, 49). It appears that either gyrase or topoisomerase IV can act ahead of replication forks (6, 25). In principle, differential targeting could arise if quinolones differed in their partitioning into critical sites of enzyme-DNA complexes within the cell. This might be achieved by interactions with other proteins that differentially mask quinolone binding sites on the two topoisomerases. Alternatively, different drugs might have differential effects on the conversion of ternary complexes into lethal lesions through the agency of helicases or polymerases and other, as-yet-unknown factors that recognize and process the complex. This could occur directly through the presence of the quinolone in the ternary complex or indirectly by additional drug binding to accessory protein factors. Further studies will be needed on ternary-complex formation and processing in S. pneumoniae.

Finally, whatever its detailed explanation, selective quinolone action through one or another topoisomerase target may occur widely in bacteria with important consequences for mechanistic studies, drug design, and the circumvention of resistance. Recent data indicate that, as in S. pneumoniae, sparfloxacin and ofloxacin select respective gyrA and parC QRDR mutants of Mycoplasma hominis (5). Moreover, in S. aureus, though most quinolones act through topoisomerase IV, nalidixic acid is reported to act through gyrase (12). Quinolones with different modes of action may be useful probes of topoisomerase function in DNA replication. On the other hand, drugs that act equally through gyrase and topoisomerase IV in vivo would be desirable in requiring changes in two genes for resistance, thereby minimizing the development of resistant strains (17, 36, 38, 39). Studies with S. pneumoniae should provide a useful paradigm in exploring these areas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

X.-S. P. was supported by a grant from Pfizer-Parke Davis Co., Ltd. G.Y. was funded by a Visiting Fellowship from the Spanish Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Sandhiya Patel for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams D E, Shekhtman E M, Zechiedrich E L, Schmid M B, Cozzarelli N R. The role of topoisomerase IV in partitioning DNA replicons and the structure of catenated intermediates in DNA replication. Cell. 1992;71:277–288. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90356-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alovero F L, Pan X-S, Morris J E, Manzo R H, Fisher L M. Engineering the specificity of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: benzenesulfonamide modifications at C-7 of ciprofloxacin change its primary target in Streptococcus pneumoniae from topoisomerase IV to gyrase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:320–325. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.320-325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin C A, Marsh K L, Wasserman R A, Willmore E, Sayer P J, Wang J C, Fisher L M. Expression, domain structure and enzymatic properties of an active recombinant human topoisomerase IIβ. J Biol Chem. 1995;276:15739–15746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett J G, Grundy L M. Community-acquired pneumonia. New Engl J Med. 1995;333:1618–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bebear C M, Renaudin H, Charron A, Bove J M, Bebear C, Renaudin J. Alterations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in quinolone-resistant mutants of Mycoplasma hominis obtained in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2304–2311. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crisona N J, Strick T R, Bensimon D, Croquette V, Cozzarelli N R. Preferential relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA by E. coli topoisomerase IV in single-molecule and ensemble measurements. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2881–2892. doi: 10.1101/gad.838900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen M E, Wyke A W, Kuroda R, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase A gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:886–894. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.6.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1554–1558. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse L, Lagneux D, Crouzet J, Famechon A A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target for quinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher L M, Mizuuchi K, O'Dea M H, Ohmori H, Gellert M. Site-specific interaction of DNA gyrase with DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4165–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher L M, Barot H A, Cullen M E. DNA gyrase complex with DNA: determinants for site-specific DNA breakage. EMBO J. 1986;5:1411–1418. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier B, Hooper D C. Mutations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase of Staphylococcus aureus: novel pleiotropic effects on quinolone and coumarin activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:121–128. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda H, Hiramatsu K. Primary targets of fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:410–412. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O'Dea M H, Itoh T, Tomizawa J-I. Nalidixic acid resistance: a second genetic character involved in DNA gyrase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4772–4776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O'Dea M H, Nash H A. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3872–3876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R, Haskell S, Schmieder B, Tankovic J, Girard D, Courvalin P, Polzer R J. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2691–2697. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaton V J, Ambler J E, Fisher L M. Potent antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin is associated with dual targeting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV, an in vitro target preference for gyrase, and enhanced stabilization of cleavable complexes in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3112–3117. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3112-3117.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiasa H, Yousef D O, Marians K J. DNA strand cleavage is required for replication fork arrest by a frozen topoisomerase-quinolone-DNA ternary complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26424–26429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang W M, Libbey J L, Van der Hoeven P, Yu S X. Bipolar localization of Bacillus subtilis topoisomerase IV: an enzyme required for chromosomal segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4652–4657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ince D, Hooper D C. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3344–3350. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3344-3350.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janoir C, Varon E, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L. A new mutation in ParE in a pneumococcal in vitro mutant resistant to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:952–955. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.952-955.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis M-D, Moreau N J, Gutmann L. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Higara S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodursky A B, Cozzarelli N R. The mechanism of inhibition of topoisomerase IV by quinolone antibacterials. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27668–27677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khodursky A B, Peter B J, Schmid M B, DeRisi J, Botstein D, Brown P O, Cozzarelli N R. Analysis of topoisomerase function in bacterial replication fork movement: use of microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9419–9424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khodursky A B, Zechiedrich E I, Cozzarelli N R. Topoisomerase IV is a target of quinolones in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11801–11805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreuzer K N, Cozzarelli N R. Escherichia coli mutants thermosensitive for deoxyribonucleic acid gyrase subunit A: effects on deoxyribonucleic acid replication, transcription and bacteriophage growth. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:424–435. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.424-435.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menzel R, Gellert M. Regulation of the genes for E. coli DNA gyrase: homeostatic control of DNA supercoiling. Cell. 1984;34:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuuchi K, Fisher L M, O'Dea M H, Gellert M. DNA gyrase action involves the introduction of transient double strand breaks into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1847–1851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morais-Cabral J H, Jackson A P, Smith C V, Shikotra N, Maxwell A, Liddington R C. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. Nature. 1997;388:903–906. doi: 10.1038/42294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrissey I, George J. Activities of fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae type II topoisomerases purified as recombinant proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2579–2585. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muñoz R, De La Campa A G. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura S. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance. J Infect Chemother. 1997;3:128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng E Y, Trucksis M, Hooper D C. Quinolone resistance mutations in topoisomerase IV: relationship to the flqA locus and genetic evidence that topoisomerase IV is the primary target and DNA gyrase is the secondary target of fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1881–1888. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oram M, Fisher L M. 4-Quinolone resistance mutations in the DNA gyrase of Escherichia coli clinical isolates identified by using the polymerase chain reaction. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:387–389. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:471–474. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV are dual targets of clinafloxacin action in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: overexpression, purification, and differential inhibition by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1129–1136. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pestova E, Millichap J J, Noskin G A, Peterson L R. Intracellular targets of moxifloxacin: a comparison with other fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:583–590. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shea M E, Hiasa H. Distinct effects of the UvrD helicase on topoisomerase-quinolone-DNA ternary complexes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14649–14658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J C. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;63:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Yamanaka L M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1647–1650. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zechiedrich E L, Cozzarelli N R. Roles of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in DNA unlinking during replication in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zechiedrich E L, Khodursky A B, Bachellier S, Schneider R, Chen D, Lilley D M, Cozzarelli N R. Roles of topoisomerases in maintaining steady-state supercoiling in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8103–8113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]