Highlights

-

•

CVD is the leading cause of death in PLWH on cART.

-

•

Manifestations of HIV-related CVD differ by sex and females have an enhanced risk for CV events.

-

•

Additional experimental studies are urgently required to understand the potential signaling mechanisms leading to the sex discrepancies in the prevalence of CV events.

Key Words: combination antiretroviral therapy, endothelial dysfunction, HIV, sex differences

Abbreviations and Acronyms: cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; cIMT, carotid intima-media thickness; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; MI, myocardial infarction; NO, nitric oxide; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PLWH, people living with HIV

Summary

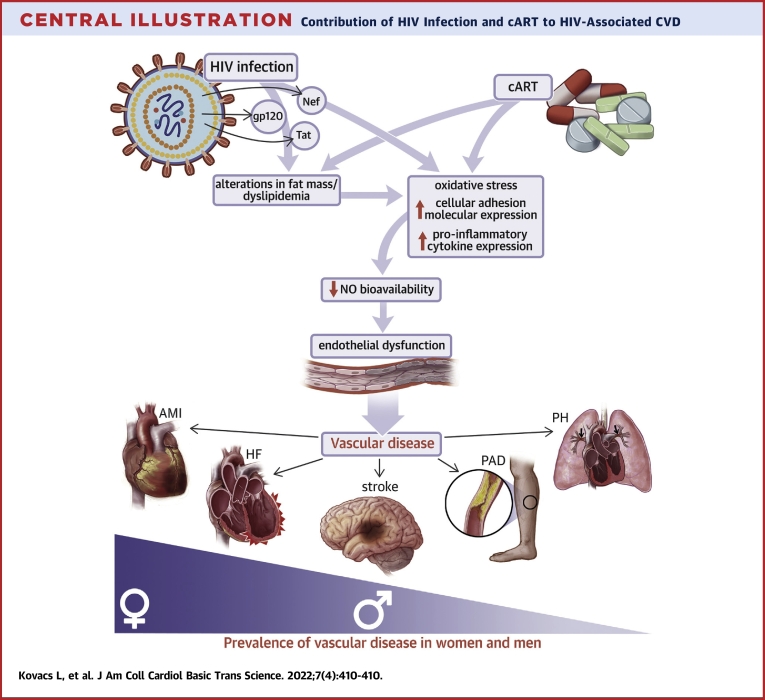

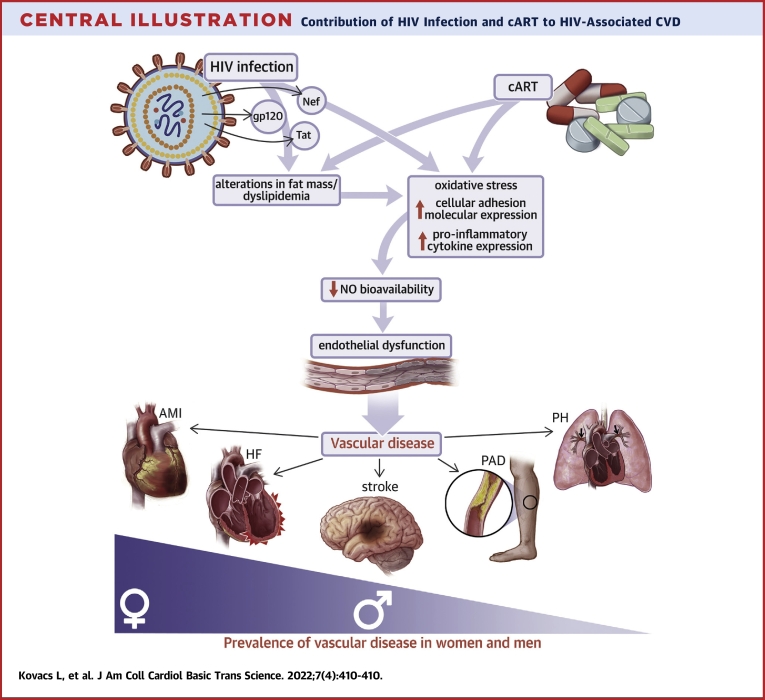

Thanks to the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (PLWH) experienced a marked increase in life expectancy but are now at higher risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), the current leading cause of death in PLWH on cART. Although HIV preponderantly affects men over women, manifestations of HIV-related CVD differ by sex with women experiencing greater risks than men. Despite extensive investigation, the etiopathology of CVD, notably the respective contribution of viral infection and cART, remain ill-defined. However, both viral infection and cART have been reported to contribute to endothelial dysfunction, the precursor and major cause of atherosclerosis-associated CVD, through mechanisms involving endothelial cell activation, inflammation, and oxidative stress, all leading to reduced nitric oxide bioavailability. Therefore, preserving endothelial function in PLWH on cART should be a main target to reduce CVD morbidity and mortality, notably in females.

Central Illustration

In 2019, approximately 38 million individuals were living with HIV/AIDS and 1.7 million people became newly infected worldwide. At the end of the same year, 25.4 million people received combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) which represents nearly 67% of HIV-infected individuals (1). Widespread access to and beneficial effects of cART, which are mainly attributable to the nearly complete inhibition of viral replication, have contributed to the dramatic reduction in mortality and resulted in a 39% decrease in AIDS-associated deaths since 2010 (1). Thanks to the advent of cART, HIV has shifted from an opportunistic, fatal disease to a noninfectious, chronic illness associated with accelerated development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) the etiology of which is still incompletely understood (2). A growing body of evidence supports the contribution of traditional risk factors (such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, obesity, and smoking), but more importantly of the HIV infection itself, and of the side effects of cART to the development of CVD (3).

People living with HIV (PLWH) now have a greater life expectancy but are at elevated risk of CVD compared to age-matched uninfected individuals, and CVD has arisen as the main cause of death in HIV-infected patients (4,5). Recent systematic studies have shown that the risk for CVD is 2-fold higher in PLWH compared to the general population, and HIV-related CVD showed a 3-fold increase from 1990 to 2015 (6). Remarkably, the rate of HIV-associated CVD is unequal between the sexes with females experiencing much greater risk for developing CVD than males (7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Additionally, female PLWH exhibit elevated rates and risks for cardiovascular (CV) events and death compared to noninfected women (12). Therefore, biological sex appears to be an additional risk factor to consider when evaluating the risk of HIV acquisition and manifestations of the disease.

Although epidemiologic observations of CVD in PLWH are important for the management of HIV infection, identification of the underlying mechanisms is necessary for the prevention and treatment of CVD in PLWH on cART. Therefore, implementation and evaluation of clinical and experimental studies are important to understand the relationship between viral infection, cART, and CVD that can lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies to treat CVD in PLWH. The aim of this review is to summarize the recent knowledge focusing on the epidemiological data on HIV-related vascular diseases including sex discrepancies, the clinical and experimental observations of the potential effect of HIV infection, and cART on vascular function and translational advances of the HIV animal models.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors of HIV-Related CVD

Many have shown that PLWH experience a wide range of vascular manifestations of CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), cerebrovascular events, peripheral artery disease (PAD), and pulmonary hypertension (PH) (13). There is a consensus that rates of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are elevated among PLWH. Studies from the United States and Europe confirmed the strong correlation between HIV and increased risk of AMI claiming that incident rates of AMI is greatly elevated in PLWH compared to the general population (8,14, 15, 16). In addition, the higher AMI risk was further increased with the existence of any CV risk factors in PLWH suggesting that reducing the traditional risk factors can attenuate the AMI risk (17). PLWH are also exposed to increased risk for HF, another major CV complication of the HIV-infected population (18). HIV infection significantly elevates the risk for HF with preserved ejection fraction, borderline HF with preserved ejection fraction, and HF with reduced ejection fraction (19). Besides these heart diseases, cerebrovascular events are also often reported as a complication of HIV and the prevalence of the disease is strikingly greater in PLWH versus people without HIV (20, 21, 22). Remarkably, the rate of cerebrovascular disease increases with age among PLWH; however, the effects of HIV status on the hazard for CVD decrease with aging, suggesting a reduction of the effect of HIV infection per se on the risk of cerebrovascular incidents in favor of a higher contribution of traditional risk factors and an increased prevalence of comorbidities in aging PLWH (9,10). A common clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis in PLWH is PAD that is associated with forthcoming CV incident such as MI and stroke (23,24). Compared to the general population, PAD occurs more often in PLWH, with a prevalence of PAD of 20.7% in PLWH versus 1% in noninfected individuals (25, 26, 27). Nonatherosclerotic CV complications of HIV include PH which has a higher incidence and poorer prognosis in PLWH compared to the general population (28,29). The most recent analysis showed that the global prevalence of PH was 8.3% in adults and 14.0% in adolescents with HIV versus a prevalence of PH of approximately 1% in noninfected individuals, indicating that PLWH are at elevated risk for this lung disorder (30,31).

Analysis of sex differences in HIV-related CVD show that female PLWH have increased risk of vascular diseases compared to males. Many have shown that AMI is more strongly associated with HIV in women than men and results from a US cohort have reported increased relative risk for the disease in women compared to men among PLWH (8). Others have also confirmed that female PLWH are exposed to higher risk of MI than males (15,32). Emerging data reveals that HIV infection is also a significant risk factor for HF in women (12). The relative risk of HF has been shown to be the highest in young people (20 to 29 years old) and in female PLWH and it displays a declining trend with age (33,34). HIV-positive women are also at a higher risk to experience stroke versus uninfected women and are at considerably greater risk for stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage than male PLWH, which collectively supports a stronger association between HIV infection and cerebrovascular events in women than men (9,10,12). PAD and PH are 2 additional vascular diseases for which sex differences have been reported and for which healthy and HIV-infected women are at elevated risk (35,36). However, noninfected women and female PLWH with PAD are more frequently asymptomatic than men and have a better survival rate than men (35, 36, 37, 38, 39). Collectively, these data indicate that the health care burden of HIV-related CVD in women will likely go beyond that of men.

Clinical Evidence of the Effect of HIV Infection and cART on Vascular Function

The pathophysiology of HIV-associated vascular diseases is complex and multifactorial. Although it is currently recognized that traditional risk factors are increased in HIV-infected individuals, the prevalence of atherosclerosis-associated CVD remains 50% higher in PLWH after adjustment for traditional risk factors such as lipids, blood pressure, and smoking status (8,14,40, 41, 42, 43). This indicates that viral infection per se and cART are independent risk factors for endothelial dysfunction and subsequent atherogenesis.

The endothelium forms the interior surface of blood vessels and plays a key role in vascular homeostasis by regulating vascular tone, nonthrombotic vascular surfaces, cell adhesion, and inflammation of the vessel wall (44). Endothelial dysfunction is characterized by diminished vasorelaxation, increased endothelial permeability, and elevated expression levels of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules (45). Compelling evidence gives credence to the idea that endothelial function is impaired in PLWH and HIV-related endothelial dysfunction has been proposed as a crucial link between infection, chronic inflammation, activation of the immune system, and atherosclerosis (46,47). Clinical assessment of endothelial function includes noninvasive measurement of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation such as flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of the brachial artery and study of markers of endothelial cell activation such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and selectins (endothelial leucocyte adhesion molecule) (48,49). Several other biomarkers including inflammatory (eg, interleukin 6 [IL-6]; C reactive protein; and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]), coagulation (eg, D-dimer and von Willebrand factor [vWF]), and immune activation (eg, soluble CD163 [sCD163] and soluble CD14 [sCD14]) are also associated with endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, quantification of the levels of expression of these markers serves as an indicator of the pathophysiological changes in vascular function (50,51). Because endothelial dysfunction is an early event in the progression of atherogenesis, examination of carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and coronary atherosclerosis by computed tomography angiography are also important surrogate markers for impaired vascular function (52,53).

Because there is no tool to identify PLWH at high CV risk and there are lacking data from large-scale randomized controlled trials of HIV therapies, the American Heart Association has recently released a scientific statement for the prevention and the management of HIV-associated CVD (54). Strategies on management of CVD in PLWH are very limited despite the fact that clinical and experimental evidence has shown the impact of novel risk factors to HIV-related CV events. Screening for endothelial dysfunction and CVD in PLWH follows the current American Heart Association recommendations for the general population including measurements of FMD, cIMT, carotid plaque, and coronary artery calcium (55, 56, 57). These methods are effective to identify HIV-infected and noninfected patients at risk for developing CVD. Lifestyle optimization such as smoking cessation, limiting alcohol consumption, and use of statin and nonstatin lipid-lowering drugs or antithrombotic agents should be considered as intervention of atherosclerosis-associated CVD (58, 59, 60, 61, 62).

Contribution of viral infection to endothelial dysfunction

In clinical settings, many studies have focused on better understanding the relationship between HIV infection/cART and the vascular biology of the endothelium. Oliviero et al (63) have shown that brachial FMD is impaired in naive untreated PLWH versus healthy patients and found a strong inverse correlation between FMD values and HIV mRNA levels, supporting a direct role for early stage of viral infection in vascular dysfunction. Plasma levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, and vWF are highly elevated in treatment-naive PLWH and show positive correlation with increased HIV viral load and the severity of the disease (64, 65, 66). Similarly, increased plasma levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein, D-dimer as well as sCD163 and sCD14 are associated with vascular dysfunction in cART-naive PLWH (67, 68, 69). Importantly, ongoing HIV replication and immune dysfunction have been shown to contribute to higher prevalence of increased biomarkers of inflammation and activation of the coagulation and immune system (70,71). Although controversial, increased cIMT, noncalcified coronary plaques, and carotid lesions appear more prevalent in PLWH and directly related to low CD4+ cell count (63,72, 73, 74, 75, 76). Collectively these data support the contribution of unrepressed HIV viral infection in the development of endothelial injury and CV events.

With the advent of cART, successful viral repression, and restoration of CD4+ T cells, the latter findings are losing clinically relevance. However, compelling evidence does support the contribution of HIV viral infection to CVD despite low viremia. Some of the best evidence is notably provided by cART-free elite controllers who, despite undetectable viral load and physiological CD4+ T cells count, exhibit increased coronary atherosclerosis and high immune activation, thus supporting a direct critical role for viral infection and its associated effects on immune activation and inflammation in the development of vascular diseases (43,77). Further evidence supporting the contribution of viral infection to vascular disease has been provided by experimental models. The Tg26 mouse and HIV-1 rat are 2 transgenic rodents that ubiquitously express 7 of 9 viral proteins and are commonly used models to investigate the effects of viral infection independent of cART treatment (78,79). As with PLWH, these animals exhibit endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherogenesis, and PH (78,80,81). Similarly, nonhuman primates infected with simian immunodeficiency virus develop atherosclerosis (82,83). Thanks to these experimental models, reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, increased inflammation, and increases in expression of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) have been identified as contributing mechanisms to endothelial dysfunction. Excess oxidative stress rather than decreases in endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and activity has been identified as the cause of reduced NO bioavailability (84,85). Ex vivo experiments in Tg26 mice reported increases in the expression of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase isoform, NOX1, in the aorta and restoration of endothelium-dependent relaxation with NOX1 inhibition (80). The HIV-1 rat, on the other hand, exhibits impaired reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging mechanisms involving decreases in superoxide dismutase and glutathione expression (84). The 2 viral proteins transactivator of transcription (tat) and negative factor (nef) are likely the origin of the increase in oxidative stress. Nef is reported to interact with p22-phox, a cofactor of NADPH oxidase NOX1 to upregulate its activity leading to increases in oxidative stress and reduction in NO bioavailability in isolated human neutrophils (86). Additionally, tat released from macrophages has the ability to increase oxidative stress in brain microvascular endothelial cells via activation of the nuclear factor κβ (NF-κβ) inflammatory pathway (87).

A common theme across the multiple in vivo models is the presence of an immune response and its contribution to the observed CVD. Tg26 mice and nonhuman primates both exhibit atherosclerosis partially mediated via the proinflammatory cytokine IL-18, a pathway which has not been examined in the HIV-1 rat (78). Despite this common theme, HIV-1 rats exhibiting PH present with increased inflammation via innate inflammatory response, histamine signaling, natural killer cell cytotoxicity, and neutrophil activation, again promoting the common theme of immune regulated CVD (81). In addition to IL-18 Tg26 mice exhibit increased inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6 (78,88). Nonhuman primates exhibit gut microbiome translocation (which can result in chronic inflammation) and inflammatory-mediated diastolic dysfunction which chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) inhibition restored (89,90). CCR5 is the entry way of HIV into uninfected cells CD4+ T cells, the primary target of HIV (91). Multiple HIV proteins interact with CCR5 including tat, which increases its expression, and envelope glycoprotein GP120 (gp120), which uses CCR5 as an entryway into the cell in vitro (78,92). Although not directly obtained in HIV conditions, CCR5 inhibition has been shown to decrease inflammation, improve endothelial function, and protect from atherogenesis, suggesting CCR5 involvement in endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease associated with viral infection (93, 94, 95). Cultured astrocytes incubated with gp120 released the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 (96). Monocytes and macrophages incubated with tat have also been shown to release TNF-related products which can lead to apoptosis in uninfected CD4 T cells (97). Finally, the nef has been shown to increase the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 when cultured with macrophages via NF-κβ mediated mechanisms (98). Collectively, these data establish a direct link between viral proteins and inflammation, which is highly clinically relevant as viral proteins remain in the circulation despite cART (99,100).

Finally, another well-established contribution to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis is the increased expression of CAMs which are able to trap monocytes causing their translocation across the endothelium (101). Tg26 mice, HIV-1 rats, and nonhuman primates all exhibit increased expression of proatherogenic adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (102,103). In in vitro studies using cultured endothelial cells, researchers have shown gp120 induced ICAM-1 expression in as little as 4 hours and tat and nef increased expression of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (104, 105, 106, 107). These in vitro studies performed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells also suggest that increases in these adhesion molecules are due to micro RNAs 221 and 222 and is NF-κβ pathway–dependent as well as the extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 pathway–dependent (105,106).

In conclusion, viral infection contributes to CVD via mechanisms which include decreased NO bioavailability, increased inflammation, and increased expression of cell adhesion molecules. These results have been corroborated with multiple approaches including Tg26 mice, HIV-1 rats, and nonhuman primates infected with simian immunodeficiency virus along with multiple in vitro models. Altogether, these models provide strong evidence of mechanisms by which HIV viral infection independent of cART contributes to CVD.

Contribution of cART to endothelial dysfunction

Analyses of the relationship between vascular dysfunction, progression rate of atherosclerosis, and cART have resulted in conflicting observations. Although evidence supports deleterious effects of cART on endothelial function, other studies report no or beneficial effects of cART Table 1 summarizes the contribution of cART regimens to CVD. Several studies have notably shown exacerbated reduction in FMD in cART-treated versus cART-naive PLWH and established independent associations between cART and diminished endothelial function, especially among PLWH receiving a regimen containing protease inhibitors (PIs) (109,110,111,118). Additional reports support a higher prevalence of cIMT, noncalcified coronary plaques, and coronary artery stenosis in cART-treated PLWH versus cART-naive patients regardless of the composition of regimen and other reports suggest further increases with longer exposure to cART (40,124,126). In contrast, others have found no association between reduced vasorelaxation and cART (regardless of the use of PI-containing regimen) nor did they report contribution of PI-containing cART to cIMT progress (72,73,108,112). Lastly, few have reported improvement of branchial FMD in HIV-infected treatment-naive patients after administration of class-sparing antiretroviral regimens (121,122).

Table 1.

Effect of cART on CVD

| cART Regimen | Outcomes Studied | Finding | First Author (Ref. #) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI (IDV, NFV, and RTV/SQV) | FMD | No change in FMD | Nolan (108) |

| PIa | cIMT | No change in cIMT | Hsue (74) |

| PI (IDV) | EDV, IMV | EDV and IMV impaired | Dubé (109) |

| (i) PI with NRTIs and/or NNRTIs or (ii) NRTIs alone or with NNRTIs PI (APV, IDV, NFV, RTV, SQV); NRTI (ABC, DDI, 3TC, d4T, AZT); NNRTI (DLV, EFV, NVP) |

FMD | (i) FMD impaired (ii) No change in FMD |

Stein (110) |

| PI regimen or non-PI regimena | FMD, cIMT | FMD impaired, cIMT increased | Charakida (111) |

| PI regimen or non-PI regimena | FMD | No change in FMD | Solages (112) |

| NRTIs with one or two PIs (IDV, RTV or SQV+RTV) | cIMT | cIMT increased | Seminari (113) |

| cART with a PI (IDV, NFV, SQV+RTV, or LPV+RTV) | PVW | Arterial stiffness increased | Schillaci (114) |

| (i) PI (IDV, NFV, RTV, SQV, NFV+ SQV or RTV+SQV) (ii) 2 NRTIs or 2NRTIs+ NNRTI |

Carotid plaque | Carotid lesions increased in PI receiving group | Maggi (115) |

| HAART with PIa | cIMT | cIMT increased | Chironi (116) |

| PI-containing regimens and NNRTI-containing regimensa | FMD | FMD impaired | Andrade (117) |

| (i) NRTI+PI or PI+NNRTI +/- NRTI (ii) NRTI + NNRTIa |

cIMT | No change in cIMT | Currier (72) |

| (i) PI regimen (NFV, IDV, LPV/RTV or dual PI) (ii) non-PI regimen (NNRTI+ NRTI) |

cIMT | No change in cIMT | Currier (73) |

| ABC-sparing regimens and ABC-containing regimens | FMD | FMD impaired | Hsue (118) |

| Combination of three drugs simultaneously (NRTIs, NNRTIs and/or PIs) PI (SQV/RTV, LPV/RTV, NFV, ATV/RTV, IDV/RTV); NRTI (3TC, AZT, ABC, TDF, DDI, d4T); NNRTI (EFV, NVP) |

FMD, cardiac perfusion PET | No change in FMD and cardiac perfusion | Lebech (119) |

| FTC/TDF/EFV | FMD | No change in FMD | Dysangco (120) |

| (i) PI-sparing regimen of NRTIs plus EFV, (ii) NNRTI-sparing regimen of NRTIs+LPV/RTV, (iii) NRTI-sparing regimen of EFV + LPV/RTV |

FMD | FMD improved in each arm | Torriani (121) |

| PI-containing (IDV, LPV/RTV) regimen followed by HAART with 2 NRTIs (AZT and 3TC) and one NNRTI (EFV) | FMD | Normalized FMD | Arildsen (122) |

| HAART with PI, HAART with NNRTIa |

cIMT cIMT |

cIMT increased No change in cIMT |

Mercie (123) |

| AZT/3TC/LPV/r or NVP/LPV/r | cIMT, arterial stiffness |

cIMT increased, femoral artery stiffness increased | van Vonderen (124) |

| PI, NNRTI, NRTI (PI: IDV, RTV, SQV, NFV, LPV, APV, AZV); NNRTI (NVP, EFV, LOV); NRTI (AZT, d4T, 3TC, ABC, DDI, DDC, TDF) | cIMT | cIMT increased | Lorenz (40) |

| HAART including PIs, NNRTI, and NRTIa | PVW | Arterial stiffness increased | Lekakis (125) |

| HAARTa | Coronary artery stenosis > 50% | Stenosis increased | Post (126) |

| 2 NRTI (d4T and 3TC) and 1 NNRTI (EFV or NVP) | PWV, cIMT | No change in arterial stiffness and cIMT | Fourie (127) |

| 2 NRTI (TDF/3TC, AZT/3TC, ABC/3TC or 3TC) plus either a NNRTI or a RTV-boosted PI | cIMT | No change in cIMT | Mosepele (128) |

3TC = lamivudine; ABC = abacavir; APV = amprenavir; ATV = atazanavir; AZT = zidovudine; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; cIMT = carotid intima-media thickness; d4T = stavudine; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DDC = zalcitabine; DDI = didanosine; DLV = delaviridine; EDV = endothelium-dependent vasodilation; EFV = efavirenz; FMD = flow-mediated dilation; FTC = emtricitabine; HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy; IDV = indinavir; IMV = insulin-mediated vasodilation; LPV/r = boosted lopinavir; LOV = Loviride; NFV = nelfinavir; NNRTIs = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTIs = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NVP = nevirapine; PET = positron emission tomography; PI = protease inhibitors; PWV = pulse wave velocity; RTV = ritonavir; SQV = saquinavir; TDF = tenofovir.

The type of drug is not disclosed.

These conflicting observations regarding the contribution of cART also translate into inconsistencies regarding the effects of cART on markers of endothelial cell activation and inflammation including ICAM, VCAM, IL6, TNFα, and vWF. Although several studies report beneficial effect of cART on endothelial activation and systemic inflammation (regardless of the type of regimen), many others indicated a lack of influence, partial effects, or a failure to normalize to the levels of these markers in noninfected individuals (129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139).

Dyslipidemia initially appeared as the key mediator of cART-related vascular disease, notably PI-mediated endothelial dysfunction (110). However, reduction in plasma cholesterol and lipid levels did not restore endothelial function in PLWH on PI-containing regimens (140). Similarly, despite raising triglyceride levels, PI treatment did not induce endothelial dysfunction in healthy volunteers (141). Therefore, whereas dyslipidemia consistently develops with PI-containing regimens, it may likely not be the leading cause of cART-associated endothelial dysfunction. Using an experimental approach consisting of submitting mice to the PI ritonavir for 4 weeks, our group proposed alternate mechanisms, which notably demonstrated that ritonavir impairs endothelial function and NO bioavailability in vivo via indirect mechanisms involving reduced adipose mass and leptin levels leading to an endothelial leptin receptor dependent increase in NOX1 and oxidative stress as well as vascular inflammation (95). In opposition to in vitro studies reporting that ritonavir alone or in combination with various other cART alters NO production, induced marked increases in IL-6 and IL-8, and secretion of soluble ICAM and VCAM in endothelial cells in culture, we ruled out direct deleterious effects of ritonavir on endothelial cell function (142). Reduction in fat mass and adipokines (leptin) secretion are among the first and main side effects on PIs (143, 144, 145); therefore, the mechanisms proposed are likely translatable to humans.

Numerous confounding factors including the many combinations of cART possible and the heterogeneity of the population studied likely explain this lack of consistent results regarding the contribution of cART on endothelial function and vascular disease. Nevertheless collectively, these data support the individual contribution of cART to CVD through indirect metabolic alterations involving reduction in fat mass and alterations in adipokines levels as well as lipid metabolism which are major risk factor for atherosclerosis (146).

Potential causes of sex-differences in vascular diseases associated with HIV

Sex-stratified analysis revealed that female PLWH are at elevated risk and rate of CV complications compared to male PLWH or noninfected women (12,33). Higher intrinsic immune activation in females has emerged as a potential explanation for this sex-discrepancy and higher prevalence of HIV-associated CVD. Notably, studies have reported that markers of innate immune activation such as CXCL10, sCD163, and sCD14 are increased and remain elevated in cART-naive and cART-treated women, respectively, compared to male PLWH (147,148). In comparison to male PLWH, women with a lower CD4+ count have higher levels of macrophage inflammatory markers including galectin-3 binding protein (Gal-3BP), sCD163, and sCD14 which is associated with greater prevalence of cIMT (149). Similarly, increased prevalence of noncalcified coronary plaques correlates with higher monocyte activation in female compared to male PLWH and noninfected individuals, and monocyte activation was further elevated with age among women versus men PLWH (150). Collectively, these data support a higher immune activation in females in response to HIV. The female sex hormones progesterone and estrogen may contribute to this sex difference via regulating the interferon-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells upon Toll-like receptor 7 stimulation. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from women produce significantly higher levels of interferon-α in response to HIV-1 that of men which is associated with greater CD8+ T cell activation at the same level of viral replication (151, 152, 153)

Some groups have shown that there is no sex difference in response to cART treatment whereas other groups demonstrated that women experience less of cART-related decrease in the main markers of inflammation and immune activation than men irrespective the type of regimen (154, 155, 156, 157). These findings may explain the sex-based discrepancies in the prevalence of HIV-related CV events. Besides sex, many confounding factors should be considered when evaluating for CVD risk assessment including race, socioeconomic status, smoking, and drug use. Among PLWH, higher prevalence and suboptimal control of traditional vascular risk factors in minority and racial groups, limited or no access to health care, excessive smoking, and substance abuse could contribute to the above-mentioned disparities (158, 159, 160, 161, 162). Female PLWH are often African American women who are exposed to higher risk of stroke and other CV events (159). In this particular female population, poor economic status, barriers to access health care, and greater added relative risk of smoking ultimately lead to a higher prevalence of CVD (160,161).

Together, these data suggest that the pathological mechanism responsible for the sex disparities in HIV-induced changes in vascular function is mainly attributable to the persistent higher immune activation and systemic inflammation potentially due to a reduced cART efficiency and other contributing factors such race/ethnicity, greater tobacco use, and poorer health-related quality of life as seen in women PLWH.

Conclusions

Although compelling evidence shows that CVD is the leading cause of death in PLWH on cART, the complexity of the disease, its multifactorial aspect, and the higher prevalence of traditional risk factors in PLWH have significantly impeded our advances in the understanding of its etiopathology. However, current compelling evidence derived from both clinical and experimental studies do strongly support independent contributions of both viral proteins and cART to endothelial dysfunction likely through indirect alterations in metabolic function and adipose mass distribution but also through sustained immune activation ultimately leading to impaired NO bioavailability and vascular dysfunction (Central Illustration). Experiments going forward would require deeper investigation of the underlying mechanisms and notably further analysis of the origin of the sex difference in the prevalence of CVD.

Central Illustration.

Contribution of HIV Infection and cART to HIV-Associated CVD

Schematic illustrating the potential mechanisms whereby viral infection and combination antiretroviral therapy contribute to vascular disease in patients living with HIV. AMI = acute myocardial infarction; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HF = heart failure; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NO = nitric oxide; PAD = peripheral artery disease; PH = pulmonary hypertension

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Support for this work was provided by NIH 1R01HL147639-01A1, and AHA 19EIA34760167 to Dr Belin de Chantemèle and AHA 21PRE830396 to Mr Kress. Dr Kovacs has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.UNAIDS UNAIDS global report on AIDS. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf

- 2.Deeks S.G., Lewin S.R., Havlir D.V. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382:1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seecheran V.K., Giddings S.L., Seecheran N.A. Acute coronary syndromes in patients with HIV. Coron Artery Dis. 2017;28:166–172. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glesby M.J. Cardiovascular complications of HIV infection. Top Antivir Med. 2017;24:127–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosn J., Taiwo B., Seedat S., Autran B., Katlama C. HIV. Lancet. 2018;392:685–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A.S.V., Stelzle D., Lee K.K., et al. Global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2018;138:1100–1112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scully E.P. Sex differences in HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15:136–146. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Triant V.A., Lee H., Hadigan C., Grinspoon S.K. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow F.C., Regan S., Feske S., Meigs J.B., Grinspoon S.K., Triant V.A. Comparison of ischemic stroke incidence in HIV-infected and non–HIV-infected patients in a US health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:351–358. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825c7f24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow F.C., He W., Bacchetti P., et al. Elevated rates of intracerebral hemorrhage in individuals from a US clinical care HIV cohort. Neurology. 2014;83:1705–1711. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durand M., Sheehy O., Baril J.G., Lelorier J., Tremblay C.L. Association between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort and nested case-control study using Quebec's public health insurance database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:245–253. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d33a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Womack J.A., Chang C.C., So-Armah K.A., et al. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinstein M.J., Bogorodskaya M., Bloomfield G.S., et al. Cardiovascular complications of HIV in endemic countries. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:113. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0794-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freiberg M.S., Chang C.C., Kuller L.H., et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang S., Mary-Krause M., Cotte L., et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS. 2010;24:1228–1230. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339192f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obel N., Thomsen H.F., Kronborg G., et al. Ischemic heart disease in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1625–1631. doi: 10.1086/518285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paisible A.L., Chang C.C., So-Armah K.A., et al. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:209–216. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remick J., Georgiopoulou V., Marti C., et al. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and future research. Circulation. 2014;129:1781–1789. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freiberg M.S., Chang C.H., Skanderson M., et al. Association between HIV infection and the risk of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and preserved ejection fraction in the antiretroviral therapy era: results from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:536–546. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sico J.J., Chang C.C., So-Armah K., et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology. 2015;84:1933–1940. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen L.D., Engsig F.N., Christensen H., et al. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25:1637–1646. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso A., Barnes A.E., Guest J.L., Shah A., Shao I.Y., Marconi V. HIV Infection and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: an analysis of a large healthcare database. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diehm C., Allenberg J.R., Pittrow D., et al. Mortality and vascular morbidity in older adults with asymptomatic versus symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2009;120:2053–2061. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poredos P., Jug B. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in high risk subjects and coronary or cerebrovascular patients. Angiology. 2007;58:309–315. doi: 10.1177/0003319707302494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belgrave K., Shaikh K., Budoff M.J. Risk of peripheral artery disease in human immunodeficiency virus infected individuals. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:S46. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Periard D., Cavassini M., Taffe P., et al. High prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in HIV-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:761–767. doi: 10.1086/527564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckman J.A., Duncan M.S., Alcorn C.W., et al. Association of human immunodeficiency virus infection and risk of peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2018;138:255–265. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almodovar S., Hsue P.Y., Morelli J., Huang L., Flores S.C., Lung H.I.V.S. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension: potential role of HIV-1 Nef. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:308–312. doi: 10.1513/pats.201006-046WR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarrett H., Barnett C. HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:566–571. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigna J.J., Kenne A.M., Asangbeh S.L., Sibetcheu A.T. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the global population with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e193–e202. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoeper M.M., Humbert M., Souza R., et al. A global view of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:306–322. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saves M., Chene G., Ducimetiere P., et al. Risk factors for coronary heart disease in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:292–298. doi: 10.1086/375844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Kindi S.G., ElAmm C., Ginwalla M., et al. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Epidemiology and management disparities. Int J Cardiol. 2016;218:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janjua S.A., Triant V.A., Addison D., et al. HIV Infection and heart failure outcomes in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foderaro A., Ventetuolo C.E. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and the sex hormone paradox. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:84. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0689-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel T., Baydoun H., Patel N.K., et al. Peripheral arterial disease in women: the gender effect. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aurpibul L., Sugandhavesa P., Srithanaviboonchai K., et al. Peripheral artery disease in HIV-infected older adults on antiretroviral treatment in Thailand. HIV Med. 2019;20:54–59. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinsch N., Buhr C., Krings P., et al. Effect of gender and highly active antiretroviral therapy on HIV-related pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the HIV-HEART Study. HIV Med. 2008;9:550–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarze-Zander C., Pabst S., Hammerstingl C., et al. Pulmonary hypertension in HIV infection: a prospective echocardiographic study. HIV Med. 2015;16:578–582. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenz M.W., Stephan C., Harmjanz A., et al. Both long-term HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy are independent risk factors for early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahbaz S., Manicardi M., Guaraldi G., Raggi P. Cardiovascular disease in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients: a true or perceived risk? World J Cardiol. 2015;7:633–644. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i10.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Althoff K.N., Gebo K.A., Moore R.D., et al. Contributions of traditional and HIV-related risk factors on non–AIDS-defining cancer, myocardial infarction, and end-stage liver and renal diseases in adults with HIV in the USA and Canada: a collaboration of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2019;6:e93–e104. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30295-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsue P.Y., Hunt P.W., Schnell A., et al. Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. AIDS. 2009;23:1059–1067. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b514b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deanfield J.E., Halcox J.P., Rabelink T.J. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285–1295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anand A.R., Rachel G., Parthasarathy D. HIV Proteins and endothelial dysfunction: implications in cardiovascular disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:185. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marincowitz C., Genis A., Goswami N., De Boever P., Nawrot T.S., Strijdom H. Vascular endothelial dysfunction in the wake of HIV and ART. FEBS J. 2019;286:1256–1270. doi: 10.1111/febs.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrade A.C., Cotter B.R. Endothelial function and cardiovascular diseases in HIV infected patient. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10:139–145. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702006000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gokce N., Keaney J.F., Jr., Hunter L.M., Watkins M.T., Menzoian J.O., Vita J.A. Risk stratification for postoperative cardiovascular events via noninvasive assessment of endothelial function: a prospective study. Circulation. 2002;105:1567–1572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012543.55874.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goncharov N.V., Nadeev A.D., Jenkins R.O., Avdonin P.V. Markers and biomarkers of endothelium: when something is rotten in the state. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:9759735. doi: 10.1155/2017/9759735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller M.M., Griesmacher A. Markers of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:77–85. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paulus P., Jennewein C., Zacharowski K. Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction: can they help us deciphering systemic inflammation and sepsis? Biomarkers. 2011;16(suppl 1):S11–S21. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.587893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tousoulis D., Antoniades C., Vlachopoulos C., Stefanadis C. Flow mediated dilation and carotid intima media thickness: clinical markers or just research tools? Int J Cardiol. 2013;163:226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achenbach S., Raggi P. Imaging of coronary atherosclerosis by computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1442–1448. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feinstein M.J., Hsue P.Y., Benjamin L.A., et al. Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e98–e124. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goff D.C., Jr., Lloyd-Jones D.M., Bennett G., et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2935–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters S.A., den Ruijter H.M., Bots M.L., Moons K.G. Improvements in risk stratification for the occurrence of cardiovascular disease by imaging subclinical atherosclerosis: a systematic review. Heart. 2012;98:177–184. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strijdom H., De Boever P., Walzl G., et al. Cardiovascular risk and endothelial function in people living with HIV/AIDS: design of the multi-site, longitudinal EndoAfrica study in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2158-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rasmussen L.D., Helleberg M., May M.T., et al. Myocardial infarction among Danish HIV-infected individuals: population-attributable fractions associated with smoking. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly S.G., Plankey M., Post W.S., et al. Associations between tobacco, alcohol, and drug use with coronary artery plaque among HIV-infected and uninfected men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silverberg M.J., Leyden W., Hurley L., et al. Response to newly prescribed lipid-lowering therapy in patients with and without HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:301–313. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-5-200903030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suchindran S., Regan S., Meigs J.B., Grinspoon S.K., Triant V.A. Aspirin use for primary and secondary prevention in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected and HIV-uninfected patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:ofu076. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bergeron N., Phan B.A., Ding Y., Fong A., Krauss R.M. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibition: a new therapeutic mechanism for reducing cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2015;132:1648–1666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oliviero U., Bonadies G., Apuzzi V., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus per se exerts atherogenic effects. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:586–589. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lafeuillade A., Alessi M.C., Poizot-Martin I., et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988) 1992;5:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nordoy I., Aukrust P., Muller F., Froland S.S. Abnormal levels of circulating adhesion molecules in HIV-1 infection with characteristic alterations in opportunistic infections. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81:16–21. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galea P., Vermot-Desroches C., Le Contel C., Wijdenes J., Chermann J.C. Circulating cell adhesion molecules in HIV1-infected patients as indicator markers for AIDS progression. Res Immunol. 1997;148:109–117. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(97)82482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sandler N.G., Wand H., Roque A., et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:780–790. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burdo T.H., Lo J., Abbara S., et al. Soluble CD163, a novel marker of activated macrophages, is elevated and associated with noncalcified coronary plaque in HIV-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1227–1236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baker J., Quick H., Hullsiek K.H., et al. Interleukin-6 and d-dimer levels are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with untreated HIV infection. HIV Med. 2010;11:608–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Armah K.A., McGinnis K., Baker J., et al. HIV status, burden of comorbid disease, and biomarkers of inflammation, altered coagulation, and monocyte activation. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:126–136. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bahrami H., Budoff M., Haberlen S.A., et al. Inflammatory markers associated with subclinical coronary artery disease: the multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Currier J.S., Kendall M.A., Zackin R., et al. Carotid artery intima-media thickness and HIV infection: traditional risk factors overshadow impact of protease inhibitor exposure. AIDS. 2005;19:927–933. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171406.53737.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Currier J.S., Kendall M.A., Henry W.K., et al. Progression of carotid artery intima-media thickening in HIV-infected and uninfected adults. AIDS. 2007;21:1137–1145. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsue P.Y., Lo J.C., Franklin A., et al. Progression of atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness in patients with HIV infection. Circulation. 2004;109:1603–1608. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124480.32233.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zanni M.V., Abbara S., Lo J., et al. Increased coronary atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability by coronary computed tomography angiography in HIV-infected men. AIDS. 2013;27:1263–1272. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835eca9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaplan R.C., Kingsley L.A., Gange S.J., et al. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. AIDS. 2008;22:1615–1624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300581d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pereyra F., Lo J., Triant V.A., et al. Increased coronary atherosclerosis and immune activation in HIV-1 elite controllers. AIDS. 2012;26:2409–2412. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835a9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kearns A.C., Liu F., Dai S., et al. Caspase-1 activation is related with HIV-associated atherosclerosis in an HIV transgenic mouse model and HIV patient cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:1762–1775. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reid W.C., Ibrahim W.G., Kim S.J., et al. Characterization of neuropathology in the HIV-1 transgenic rat at different ages. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;292:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kress T.C., Nascimento T.B., Kennard S., et al. HIV increases basal metabolic rate, impairs endothelial function and elevates blood pressure in male and female mice. FASEB J. 2020;34:1. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lund A.K., Lucero J., Herbert L., Liu Y., Naik J.S. Human immunodeficiency virus transgenic rats exhibit pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L315–L326. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00045.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams K., Lackner A., Mallard J. Non-human primate models of SIV infection and CNS neuropathology. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;19:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kearns A.C., Robinson J.A., Shekarabi M., Liu F., Qin X., Burdo T.H. Caspase-1–associated immune activation in an accelerated SIV-infected rhesus macaque model. J Neurovirol. 2018;24:420–431. doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kline E.R., Kleinhenz D.J., Liang B., et al. Vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide depletion in HIV-1 transgenic rats are reversed by glutathione restoration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2792–H2804. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91447.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wingler K., Hermans J.J., Schiffers P., Moens A., Paul M., Schmidt H.H. NOX1, 2, 4, 5: counting out oxidative stress. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:866–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zalba G., San Jose G., Moreno M.U., Fortuno A., Diez J. NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative stress: genetic studies of the p22(phox) gene in hypertension. Antiox Redox Signal. 2005;7:1327–1336. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Toborek M., Lee Y.W., Pu H., et al. HIV-Tat protein induces oxidative and inflammatory pathways in brain endothelium. J Neurochem. 2003;84:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De S.K., Devadas K., Notkins A.L. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-transgenic mice: prevention of death by antibody to TNF-alpha. J Virol. 2002;76:11710–11714. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11710-11714.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Troseid M., Manner I.W., Pedersen K.K., Haissman J.M., Kvale D., Nielsen S.D. Microbial translocation and cardiometabolic risk factors in HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2014;30:514–522. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kelly K.M., Tocchetti C.G., Lyashkov A., et al. CCR5 inhibition prevents cardiac dysfunction in the SIV/macaque model of HIV. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilen C.B., Tilton J.C., Doms R.W. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Boncompain G., Herit F., Tessier S., et al. Targeting CCR5 trafficking to inhibit HIV-1 infection. Sci Adv. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patterson B.K., Seethamraju H., Dhody K., et al. CCR5 inhibition in critical COVID-19 patients decreases inflammatory cytokines, increases CD8 T-cells, and decreases SARS-CoV2 RNA in plasma by day 14. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cipriani S., Francisci D., Mencarelli A., et al. Efficacy of the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc in reducing early, ritonavir-induced atherogenesis and advanced plaque progression in mice. Circulation. 2013;127:2114–2124. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bruder-Nascimento T., Kress T.C., Kennard S., Belin de Chantemele E.J. HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir impairs endothelial function via reduction in adipose mass and endothelial leptin receptor-dependent increases in NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1), C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5), and inflammation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ronaldson P.T., Bendayan R. HIV-1 viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 triggers an inflammatory response in cultured rat astrocytes and regulates the functional expression of P-glycoprotein. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1087–1098. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang Y., Tikhonov I., Ruckwardt T.J., et al. Monocytes treated with human immunodeficiency virus Tat kill uninfected CD4(+) cells by a tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-induced ligand-mediated mechanism. J Virol. 2003;77:6700–6708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6700-6708.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olivetta E., Percario Z., Fiorucci G., et al. HIV-1 Nef induces the release of inflammatory factors from human monocyte/macrophages: involvement of Nef endocytotic signals and NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2003;170:1716–1727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Poggi A., Carosio R., Fenoglio D., et al. Migration of V delta 1 and V delta 2 T cells in response to CXCR3 and CXCR4 ligands in healthy donors and HIV-1-infected patients: competition by HIV-1 Tat. Blood. 2004;103:2205–2213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xiao H., Neuveut C., Tiffany H.L., et al. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc of Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11466–11471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nageh M.F., Sandberg E.T., Marotti K.R., et al. Deficiency of inflammatory cell adhesion molecules protects against atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1517–1520. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.8.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Villinger F., Folks T.M., Lauro S., et al. Immunological and virological studies of natural SIV infection of disease-resistant nonhuman primates. Immunol Lett. 1996;51:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hag A.M., Kristoffersen U.S., Pedersen S.F., Gutte H., Lebech A.M., Kjaer A. Regional gene expression of LOX-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 in aorta of HIV-1 transgenic rats. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ren Z., Yao Q., Chen C. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 120 increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression by human endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2002;82:245–255. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Duan M., Yao H., Hu G., Chen X., Lund A.K., Buch S. HIV Tat induces expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs: implications for miR-221/-222 in HIV-associated cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fan Y., Liu C., Qin X., Wang Y., Han Y., Zhou Y. The role of ERK1/2 signaling pathway in Nef protein upregulation of the expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in endothelial cells. Angiology. 2010;61:669–678. doi: 10.1177/0003319710364215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu K., Chi D.S., Li C., Hall H.K., Milhorn D.M., Krishnaswamy G. HIV-1 Tat protein-induced VCAM-1 expression in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells and its signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L252–L260. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00200.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nolan D., Watts G.F., Herrmann S.E., French M.A., John M., Mallal S. Endothelial function in HIV-infected patients receiving protease inhibitor therapy: does immune competence affect cardiovascular risk? QJM. 2003;96:825–832. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dube M.P., Gorski J.C., Shen C. Severe impairment of endothelial function with the HIV-1 protease inhibitor indinavir is not mediated by insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2008;8:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-9010-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stein J.H., Klein M.A., Bellehumeur J.L., et al. Use of human immunodeficiency virus-1 protease inhibitors is associated with atherogenic lipoprotein changes and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;104:257–262. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Charakida M., Donald A.E., Green H., et al. Early structural and functional changes of the vasculature in HIV-infected children: impact of disease and antiretroviral therapy. Circulation. 2005;112:103–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Solages A., Vita J.A., Thornton D.J., et al. Endothelial function in HIV-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1325–1332. doi: 10.1086/503261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Seminari E., Pan A., Voltini G., et al. Assessment of atherosclerosis using carotid ultrasonography in a cohort of HIV-positive patients treated with protease inhibitors. Atherosclerosis. 2002;162:433–438. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schillaci G., De Socio G.V., Pirro M., et al. Impact of treatment with protease inhibitors on aortic stiffness in adult patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2381–2385. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000183744.38509.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Maggi P., Serio G., Epifani G., et al. Premature lesions of the carotid vessels in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors. AIDS. 2000;14:F123–F128. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chironi G., Escaut L., Gariepy J., et al. Brief report: carotid intima-media thickness in heavily pretreated HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:490–493. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Andrade A.C., Ladeia A.M., Netto E.M., et al. Cross-sectional study of endothelial function in HIV-infected patients in Brazil. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:27–33. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hsue P.Y., Hunt P.W., Wu Y., et al. Association of abacavir and impaired endothelial function in treated and suppressed HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2009;23:2021–2027. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lebech A.M., Kristoffersen U.S., Wiinberg N., et al. Coronary and peripheral endothelial function in HIV patients studied with positron emission tomography and flow-mediated dilation: relation to hypercholesterolemia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2049–2058. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dysangco A., Liu Z., Stein J.H., Dube M.P., Gupta S.K. HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and measures of endothelial function, inflammation, metabolism, and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Torriani F.J., Komarow L., Parker R.A., et al. Endothelial function in human immunodeficiency virus-infected antiretroviral-naive subjects before and after starting potent antiretroviral therapy: the ACTG (AIDS Clinical Trials Group) study 5152s. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Arildsen H., Sorensen K.E., Ingerslev J.M., Ostergaard L.J., Laursen A.L. Endothelial dysfunction, increased inflammation, and activated coagulation in HIV-infected patients improve after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2013;14:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mercie P., Thiebaut R., Lavignolle V., et al. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors in HIV-1 infected patients using carotid intima-media thickness measurement. Ann Med. 2002;34:55–63. doi: 10.1080/078538902317338652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.van Vonderen M.G., Hassink E.A., van Agtmael M.A., et al. Increase in carotid artery intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness but improvement in several markers of endothelial function after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1186–1194. doi: 10.1086/597475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lekakis J., Ikonomidis I., Palios J., et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy with increased arterial stiffness in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:828–834. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Post W.S., Budoff M., Kingsley L., et al. Associations between HIV infection and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:458–467. doi: 10.7326/M13-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fourie C.M., Schutte A.E., Smith W., Kruger A., van Rooyen J.M. Endothelial activation and cardiometabolic profiles of treated and never-treated HIV infected Africans. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mosepele M., Mohammed T., Mupfumi L., et al. HIV disease is associated with increased biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction despite viral suppression on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2018;29:155–161. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2018-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Okello S., Asiimwe S.B., Kanyesigye M., et al. D-Dimer levels and traditional risk factors are associated with incident hypertension among HIV-infected individuals initiating antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:396–402. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Calmy A., Gayet-Ageron A., Montecucco F., et al. HIV increases markers of cardiovascular risk: results from a randomized, treatment interruption trial. AIDS. 2009;23:929–939. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32832995fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ross A.C., Armentrout R., O'Riordan M.A., et al. Endothelial activation markers are linked to HIV status and are independent of antiretroviral therapy and lipoatrophy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:499–506. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318189a794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.McComsey G.A., Kitch D., Daar E.S., et al. Inflammation markers after randomization to abacavir/lamivudine or tenofovir/emtricitabine with efavirenz or atazanavir/ritonavir. AIDS. 2012;26:1371–1385. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354f4fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kristoffersen U.S., Kofoed K., Kronborg G., Giger A.K., Kjaer A., Lebech A.M. Reduction in circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected patients during antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2009;10:79–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Francisci D., Giannini S., Baldelli F., et al. HIV type 1 infection, and not short-term HAART, induces endothelial dysfunction. AIDS. 2009;23:589–596. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328325a87c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Calza L., Pocaterra D., Pavoni M., et al. Plasma levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-Selectin, and P-Selectin in 99 HIV-positive patients versus 51 HIV-negative healthy controls. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:430–432. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819a292c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Funderburg N.T. Markers of coagulation and inflammation often remain elevated in ART-treated HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:80–86. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wolf K., Tsakiris D.A., Weber R., Erb P., Battegay M., Swiss H.I.V.C.S. Antiretroviral therapy reduces markers of endothelial and coagulation activation in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:456–462. doi: 10.1086/338572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Baker J.V., Neuhaus J., Duprez D., et al. Changes in inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers: a randomized comparison of immediate versus deferred antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:36–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f7f61a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Burdo T.H., Lentz M.R., Autissier P., et al. Soluble CD163 made by monocyte/macrophages is a novel marker of HIV activity in early and chronic infection prior to and after anti-retroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:154–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Murphy R.L., Berzins B., Zala C., et al. Change to atazanavir/ritonavir treatment improves lipids but not endothelial function in patients on stable antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2010;24:885–890. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283352ed5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dube M.P., Shen C., Greenwald M., Mather K.J. No impairment of endothelial function or insulin sensitivity with 4 weeks of the HIV protease inhibitors atazanavir or lopinavir-ritonavir in healthy subjects without HIV infection: a placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:567–574. doi: 10.1086/590154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Auclair M., Afonso P., Capel E., Caron-Debarle M., Capeau J. Impact of darunavir, atazanavir and lopinavir boosted with ritonavir on cultured human endothelial cells: beneficial effect of pravastatin. Antivir Ther. 2014;19:773–782. doi: 10.3851/IMP2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Carr A., Samaras K., Burton S., et al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1998;12:F51–F58. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Estrada V., Serrano-Rios M., Martinez Larrad M.T., et al. Leptin and adipose tissue maldistribution in HIV-infected male patients with predominant fat loss treated with antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:32–40. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200201010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Nagy G.S., Tsiodras S., Martin L.D., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are associated with serum concentrations of leptin. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:795–802. doi: 10.1086/367859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.van Wijk J.P., Cabezas M.C. Hypertriglyceridemia, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients: effects of antiretroviral therapy and adipose tissue distribution. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:201027. doi: 10.1155/2012/201027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Martin G.E., Gouillou M., Hearps A.C., et al. Age-associated changes in monocyte and innate immune activation markers occur more rapidly in HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Li J.Z., Arnold K.B., Lo J., et al. Differential levels of soluble inflammatory markers by human immunodeficiency virus controller status and demographics. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofu117. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shaked I., Hanna D.B., Gleissner C., et al. Macrophage inflammatory markers are associated with subclinical carotid artery disease in women with human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus infection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1085–1092. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Fitch K.V., Srinivasa S., Abbara S., et al. Noncalcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque and immune activation in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1737–1746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hughes G.C., Thomas S., Li C., Kaja M.K., Clark E.A. Cutting edge: progesterone regulates IFN-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:2029–2033. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Griesbeck M., Ziegler S., Laffont S., et al. Sex differences in plasmacytoid dendritic cell levels of IRF5 drive higher IFN-alpha production in women. J Immunol. 2015;195:5327–5336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Meier A., Chang J.J., Chan E.S., et al. Sex differences in the Toll-like receptor-mediated response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to HIV-1. Nat Med. 2009;15:955–959. doi: 10.1038/nm.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Moore A.L., Kirk O., Johnson A.M., et al. Virologic, immunologic, and clinical response to highly active antiretroviral therapy: the gender issue revisited. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:452–461. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Squires K., Bekker L.G., Katlama C., et al. Influence of sex/gender and race on responses to raltegravir combined with tenofovir-emtricitabine in treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-1 infected patients: pooled analyses of the STARTMRK and QDMRK studies. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofw047. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Mathad J.S., Gupte N., Balagopal A., et al. Sex-related differences in inflammatory and immune activation markers before and after combined antiretroviral therapy initiation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:123–129. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Ticona E., Bull M.E., Soria J., et al. Biomarkers of inflammation in HIV-infected Peruvian men and women before and during suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2015;29:1617–1622. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Gutierrez J., Williams O.A. A decade of racial and ethnic stroke disparities in the United States. Neurology. 2014;82:1080–1082. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Chow F.C., Wilson M.R., Wu K., Ellis R.J., Bosch R.J., Linas B.P. Stroke incidence is highest in women and non-Hispanic blacks living with HIV in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials cohort. AIDS. 2018;32:1125–1135. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Johnson M., Samarina A., Xi H., et al. Barriers to access to care reported by women living with HIV across 27 countries. AIDS Care. 2015;27:1220–1230. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1046416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Weinberger A.H., Smith P.H., Funk A.P., Rabin S., Shuter J. Sex differences in tobacco use among persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74:439–453. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Durvasula R., Miller T.R. Substance abuse treatment in persons with HIV/AIDS: challenges in managing triple diagnosis. Behav Med. 2014;40:43–52. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2013.866540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]