Abstract

Background

ESMO COVID-19 and CAncer REgistry (ESMO-CoCARE) is an international collaborative registry-based, cohort study gathering real-world data from Europe, Asia/Oceania and Africa on the natural history, management and outcomes of patients with cancer infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Patients and methods

ESMO-CoCARE captures information on patients with solid/haematological malignancies, diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Data collected since June 2020 include demographics, comorbidities, laboratory measurements, cancer characteristics, COVID-19 clinical features, management and outcome. Parameters influencing COVID-19 severity/recovery were investigated as well as factors associated with overall survival (OS) upon SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

This analysis includes 1626 patients from 20 countries (87% from 24 European, 7% from 5 North African, 6% from 8 Asian/Oceanian centres), with COVID-19 diagnosis from January 2020 to May 2021. Median age was 64 years, with 52% of female, 57% of cancer stage III/IV and 65% receiving active cancer treatment. Nearly 64% patients required hospitalization due to COVID-19 diagnosis, with 11% receiving intensive care. In multivariable analysis, male sex, older age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≥2, body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2, presence of comorbidities, symptomatic disease, as well as haematological malignancies, active/progressive cancer, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) ≥6 and OnCovid Inflammatory Score ≤40 were associated with COVID-19 severity (i.e. severe/moderate disease requiring hospitalization). About 98% of patients with mild COVID-19 recovered, as opposed to 71% with severe/moderate disease. Advanced cancer stage was an additional adverse prognostic factor for recovery. At data cut-off, and with median follow-up of 3 months, the COVID-19-related death rate was 24.5% (297/1212), with 380 deaths recorded in total. Almost all factors associated with COVID-19 severity, except for BMI and NLR, were also predictive of inferior OS, along with smoking and non-Asian ethnicity.

Conclusions

Selected patient and cancer characteristics related to sex, ethnicity, poor fitness, comorbidities, inflammation and active malignancy predict for severe/moderate disease and adverse outcomes from COVID-19 in patients with cancer.

Key words: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, oncology, cancer

Highlights

-

•

ESMO-CoCARE is an international registry on COVID-19 in patients with cancer from centres in Europe, Asia/Oceania and Africa.

-

•

Analysis is based on a total of 1626 patients, with 3-month median follow-up.

-

•

Overall, 64% had moderate/severe COVID-19 and at data cut-off the COVID-19-related death rate was 25%.

-

•

Risk factors for COVID-19 severity included patient and cancer-related characteristics, and systemic inflammation.

-

•

Our data add evidence to support clinicians and regulatory bodies for the management of COVID-19 in patients with cancer.

Introduction

In the beginning of 2020, a striking increase in cases and deaths from a new virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), and its disease [coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)], startled the worldwide community. Clinical features associated with COVID-19 included fever, fatigue, dry cough, acute respiratory distress syndrome, blood test abnormalities or ground-glass opacity in the lungs.1,2 In addition, analysis from initial studies identified older age, diabetes, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and malignant disease as risk factors for COVID-19 severity.1,2

Patients with cancer commonly have an immune dysfunction due to the use of immunosuppressive medicines (e.g. cytotoxic drugs, corticosteroids), poor nutritional status or direct effects of the tumour on the fitness of the immune system.3,4 They also represent an older population frequently with severe comorbidities. It was, thus, hypothesized that patients with cancer would be at higher risk of experiencing severe COVID-19.3, 4, 5 Rapid changes in cancer care and research were implemented globally,6, 7, 8 while screening and diagnostic programmes were severely affected, with subsequent higher prevalence of more advanced-stage presentation.7,9,10 To mitigate these evolving issues, several cancer societies developed and regularly updated specific guidelines for cancer care, despite the limited availability of data-driven evidence.11 An urgent need to study the effects of COVID-19 in patients with cancer emerged and several international groups started to collaborate worldwide, with a swift set up of dedicated clinically oriented databases to address this new priority and unmet need.12, 13, 14

Several publications reported on the deleterious effects of COVID-19 in specific subgroups of patients with cancer1,2,15, 16, 17; however, the heterogeneous data collection and lack of statistical power were important limitations leading, in some cases, to contradictory results.16 It became, therefore, essential to gather larger and more robust datasets powered to study the effects of COVID-19 in different subgroups of patients with cancer (i.e. histology, staging, treatments) from various geographic areas.

The ESMO COVID-19 and CAncer REgistry (ESMO-CoCARE) was initiated to meet this goal and was designed as a large, observational multicentre, transnational database, including centres from Europe, Africa and Asia/Oceania to study the effects of COVID-19 in patients with hematologic or solid tumours. Herein, we present the first ESMO-CoCARE results with data collected until May 2021. We report on risk factors for severity and mortality from COVID-19 in patients with cancer integrating data from centres in Europe, Asia/Oceania and Africa, and we independently validate observations from similar registries, in an effort to contribute to a better understanding of COVID-19 disease in people with cancer, informing clinicians and regulatory bodies on optimal management.

Methodology

Study design and participants

The ESMO-CoCARE is an observational prospective study, based on a longitudinal multicentre survey of patients with cancer with any solid or haematological malignancy who were diagnosed with COVID-19. The data reside in the ESMO-CoCARE registry, developed and maintained as an electronic REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database housed at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV) in Lausanne, Switzerland. Active data collection is planned until the end of the pandemic as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO), or the end of epidemic situation in each region, with subsequent follow-up as needed.

Data on clinical features, course of the disease, management and outcomes are collected for both cancer and COVID-19 disease. The aim of the study is primarily descriptive of the characteristics of COVID-19 in patients with cancer, exploring associations with both cancer and COVID-19 outcomes. Data reported here were extracted from medical records of consecutive patients diagnosed with COVID-19 from 1 January 2020 up to 18 May 2021. COVID-19 diagnosis included both laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases (irrespective of symptoms and clinical presentation) and cases with only clinical diagnosis of COVID-19, based on signs such as fever >38°C, cough, diarrhoea, otitis, dysgeusia, anosmia, myalgia, arthralgia, conjunctivitis and rhinorrhoea, lymphocyte count <1.0 × 109/l, and/or chest radiographic or lung computed tomography imaging suggestive of SARS-CoV-2-19 pneumonia.

Study objectives and endpoints

The objectives of this study included the identification of risk factors predictive of severity, in terms of hospitalization, or recovery from COVID-19 in patients with cancer, and overall survival (OS). In the current analysis, the following endpoints were considered as co-primary: COVID-19 severity was categorized based on hospitalization requirement and indication for intensive care unit (ICU) admission (mild: no hospitalization; moderate: hospitalization indicated/took place, without ICU admission; severe: ICU indication/admission). In the univariate/multivariable analyses performed the following grouping was used: moderate/severe (hospitalization required) versus mild (no hospitalization).

Recovery from COVID-19 illness was defined by the rate of patients with COVID-19 who survived the disease, having a date of recovery reported. OS was defined as the time from COVID-19 diagnosis to death from any cause. OS was assessed for patients with available follow-up information, that is, date of death for reported deaths or date of last follow-up for those alive.

Statistical analysis

All the variables of interest were described overall and by the primary outcomes of COVID-19 severity/recovery and OS.

Mann–Whitney and Fisher’s exact tests were used for the associations of continuous and categorical variables, respectively, with COVID-19 severity and recovery, while the associations with OS were explored through log-rank test. Univariable logistic and Cox proportional hazards models were also fitted, for COVID-19 severity/recovery and OS, respectively. Of note, no adjustment of multiple comparisons was performed, and differences were primarily descriptive. Other associations of interest were assessed through Fisher’s exact test (e.g. treatment adjustment due to COVID-19 with type of cancer treatment, symptoms and COVID-19 complications with demographics, and others). OS was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method for the whole analysis cohort with available follow-up information. In the frame of OS analysis, COVID-19-related mortality, that is, deaths reported for patients who did not recover, as well as deaths reported for patients who recovered but died later due to COVID-19 complications, was also assessed.

Multivariable models were also fitted: logistic for COVID-19 severity/recovery and Cox proportional hazards for OS. A preselection of baseline variables to be included in the multivariable models was processed to avoid overfitting. Variable selection was based on significance from the univariable analysis (P < 0.10), clinical relevance, degree of factor missingness and possible correlation between candidate predictors. Of note, because almost all patients who were not hospitalized finally recovered, multivariable analysis for identifying risk factors for recovery focused only on the hospitalized patients (moderate/severe disease).

The variables initially included were gender, age, ethnicity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), smoking status, BMI (<25 kg/m2 versus ≥25 kg/m2), comorbidities, cancer type/stage/status at COVID-19 diagnosis, COVID-19 symptoms (symptomatic/asymptomatic) and the following inflammation-based biomarkers measured prior to COVID-19 diagnosis: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), OnCovid Inflammatory Score (OIS). The backward elimination method with removal criterion P >0.10 was utilized to obtain the factors with significant effects. Multicollinearity and proportionality assumption based on the Schoenfeld residuals were checked. Data were analysed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.0.0 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) software.

Results

Cohort description and cancer disease characteristics

From January 2020 to May 2021, a total of 1626 eligible patients with COVID-19 diagnosis and a history of active malignancy or in remission were registered in the CoCARE database and comprised the analysis cohort. COVID-19 was diagnosed most often in March and April 2020 (16.6% and 16.1%, respectively), followed by December 2020 and January 2021 (12.2% and 11.8%, respectively; Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499.).

Registration of patients was performed at 37 participating centres in 20 countries, from 6 June 2020 to 18 May 2021. United Kingdom (32%) and Spain (24%) contributed the highest proportion of patients, with 31% from other European countries; 7% and 6% were registered from African and Asian/Oceanian countries, respectively (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499).

Cohort demographics, clinical and cancer disease characteristics, are presented in Table 1. Overall, approximately half of the patients were female (52%), with a median age of 64 years, including 563 patients (35%) older than 70 years. Most of the patients were Caucasian (58%). Almost 50% of the patients had ECOG PS = 1, while 41% were never smokers (never exposed to active smoking). BMI was recorded for 82% of patients, with 547 of them (41%) having BMI <25 kg/m2 [most of whom (n = 490) with 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 kg/m2], 502 (38%) being overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) and 280 (21%) obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Table 1.

Cohort demographics, clinical and cancer disease characteristics (n = 1626)

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 1626) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 845 (52.0) |

| Male | 757 (46.6) |

| Unknown/missing | 24 (1.5) |

| Age (years at COVID-19 diagnosis), n (%) | |

| ≤49 | 303 (18.6) |

| 50-69 | 735 (45.2) |

| ≥70 | 563 (34.6) |

| Unknown/missing | 25 (1.5) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 64 (53-73) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 942 (57.9) |

| Non-Caucasian | 466 (28.7) |

| Asian | 117 (7.2) |

| Othera | 349 (21.5) |

| Unknown/missing | 218 (13.4) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 342 (21.0) |

| 1 | 758 (46.6) |

| 2 | 273 (16.8) |

| ≥3 | 114 (7.0) |

| Unknown/missing | 139 (8.5) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 148 (9.1) |

| Former smoker | 373 (22.9) |

| Never smoker | 658 (40.5) |

| Unknown/missing | 447 (27.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), n (%) | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 57 (3.5) |

| Normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25) | 490 (30.1) |

| Overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30) | 502 (30.9) |

| Obesity (≥30) | 280 (17.2) |

| Unknown/missing | 297 (18.3) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 25 (22-29) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | |

| 0 | 447 (27.5) |

| 1 | 510 (31.4) |

| >1 | 624 (38.4) |

| Unknown/missing | 45 (2.8) |

| Number of concomitant medications, n (%) | |

| 0 | 501 (30.8) |

| ≥1 | 956 (58.8) |

| Unknown/missing | 169 (10.4) |

| Cancer disease characteristics | |

| Date of cancer diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Within the past year | 758 (46.6) |

| Within the past 5 years | 552 (33.9) |

| More than 5 years ago | 210 (12.9) |

| Unknown/missing | 106 (6.5) |

| Primary tumour type, n (%) | |

| Breast | 332 (20.4) |

| Colorectal | 234 (14.4) |

| Lung | 221 (13.6) |

| Other solid tumour | 619 (38.1) |

| Haematological malignancy | 151 (9.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 69 (4.2) |

| Cancer status at COVID-19 diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Active disease, complete response | 56 (3.4) |

| Active disease, partial response | 129 (7.9) |

| Active disease, stable disease | 519 (31.9) |

| Active disease, progressive disease | 368 (22.6) |

| NED | 335 (20.6) |

| Unknown/missing | 219 (13.5) |

| Cancer stage at COVID-19 diagnosis, n (%) | |

| I | 65 (4.0) |

| II | 162 (10.0) |

| III | 242 (14.9) |

| IV | 688 (42.3) |

| Not applicableb | 395 (24.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 74 (4.6) |

| On anticancer treatment at COVID-19 diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Yes (up to 3 months prior to COVID-19 diagnosis) | 1053 (64.8) |

| No | 424 (26.1) |

| Unknown/missing | 149 (9.2) |

| Past systemic treatment, n (%) | |

| Yes | 707 (43.5) |

| No | 661 (40.7) |

| Unknown/missing | 258 (15.9) |

BMI, body mass index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NED, no evidence of disease.

Current smoker: exposed to active smoking; Former smoker: previously exposed to active smoking; Never smoker: never exposed to active smoking.

Including African, Arab/Middle Eastern, Latino American, Mediterranean, Pacific Islander/Māori and other.

The ‘not applicable’ cancer stage category includes cases for which cancer stage could not be determined: due to patient’s cancer type or because cancer restaging was not available.

Regarding clinical characteristics, the majority of the patients had pre-existing comorbidities (70%), with the most common being cardiovascular (42%), metabolic (26%) and pulmonary co-morbidities (14% Table 1, Supplementary Table S2a and b, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Furthermore, almost 60% of the patients received at least one concomitant medication. With respect to cancer disease characteristics, 47% of patients were diagnosed with cancer within the past year. The majority (86%) were solid tumours (breast: 20%, colorectal: 14%, lung: 14%, other: 38%), with haematological malignancies reported only for 9% of the patients. Most patients had evidence of active disease at COVID-19 diagnosis (66%), with 21% having no evidence of disease. Over half of the patients had cancer stage III or IV (57%; Table 1).

A total of 1053 patients (65%) were receiving anticancer treatment. Among them, most were on cytotoxic chemotherapy (69%) or on targeted therapy (15%; Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). For 56% of the patients, the treatment plan was not adjusted due to COVID-19 (Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Treatment adjustment was more often observed for patients on targeted therapy compared with treatments other than targeted (41% versus 29%), and less often for patients on radiotherapy compared with treatments other than radiotherapy (21% versus 32%; Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Of note, the association of BMI with specific cancer treatments and type/status/stage of cancer was also explored; it was significantly correlated only with cancer type (P = 0.0011), with >60% of patients with breast or colorectal cancer being overweight/obese (Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499).

COVID-19 diagnosis and course of illness

Information on COVID-19 diagnosis, course of illness and recovery is provided in Table 2. COVID-19 was confirmed based on laboratory tests for the majority of the patients (76%), including 65% with RT-PCR and 9% with SARS-CoV-2 serologic test.

Table 2.

COVID-19 diagnosis, course of illness and recovery (n = 1626)

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 1626) |

|---|---|

| COVID-19 suspicion confirmed with laboratory tests, n (%) | |

| RT-PCR | 1050 (64.6) |

| SARS-CoV-2 serology | 126 (7.7) |

| Serum Ig, Ig subtypes | 21 (1.3) |

| Other (blood cultures/swab/vector-best system) | 31 (1.9) |

| Not confirmed | 175 (10.8) |

| Unknown/missing | 223 (13.7) |

| Symptoms, n (%)a | |

| Yes (symptomatic) | 1167 (71.8) |

| Fever (>38°C) | 797 (49.0) |

| Cough (including productive cough) | 745 (45.8) |

| Dyspnoea | 542 (33.3) |

| Severe fatigue | 333 (20.5) |

| Myalgia | 218 (13.4) |

| Headache | 185 (11.4) |

| Other(including symptoms experienced by <10% of the patients) | 638 (39.2) |

| No (asymptomatic) | 280 (17.2) |

| Unknown/missing | 179 (11.0) |

| Primary endpoint: severity of COVID-19 illness, n (% excluding ‘unknown/missing’) | |

| Mild (no hospitalization took place) | 562 (36.2) |

| Moderate (hospitalization took place or indicated, but no ICU) | 822 (53.0) |

| Severe (ICU admission or at least indication) | 168 (10.8) |

| Unknown/missing | 74 |

| Complications occurring during COVID-19, n (%) | |

| At least one | 641 (39.4) |

| Pulmonary | 477 (29.3) |

| Cardiovascular | 182 (11.2) |

| Systemic | 156 (9.6) |

| Gastrointestinal | 86 (5.3) |

| Other | 260 (16.0) |

| None | 917 (56.4) |

| Unknown/missing | 68 (4.2) |

| Requirement of oxygen during the illness, n (%) | |

| Yes | 609 (37.5) |

| No | 821 (50.5) |

| Unknown/missing | 196 (12.1) |

| Receipt of any treatment for COVID-19 or its sequelae, n (%) | |

| Yes | 795 (48.9) |

| No | 819 (50.4) |

| Unknown/missing | 12 (0.7) |

| Primary endpoint: recovery from COVID-19, n (% excluding ‘unknown/missing’) | |

| Yes | 1253 (80.5) |

| No (COVID-19 deathb) | 304 (19.5) |

| Unknown/missing | 69 |

| Primary endpoint: overall survival status, n (% excluding ‘unknown/missing’) | |

| Alive (at last follow-up) | 832 (68.6) |

| Dead (with death date available) | 380 (31.4) |

| Unknown/missing (nonavailable follow-up) | 414 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; Ig, immunoglobulin; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

A detailed table with all symptoms is provided in the supplement (Supplementary Table S6a, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499).

Death date was not reported for 8 of the 304 patients that did not recover from COVID-19.

At initial presentation of COVID-19, 1167 patients (72%) had at least one symptom, with the most frequent being fever (49%), cough (including productive cough; 46%), dyspnoea (33%), severe fatigue (21%), myalgia (13%) and headache (11%;details in Supplementary Table S6a, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499).

Symptoms were reported more often by older patients, non-Caucasian, of higher ECOG PS, with pre-existing co-morbidities or with lung cancer (Supplementary Table S6b-d, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Of note, patients with no evidence of malignant disease appeared more often to be symptomatic compared with those diagnosed in the presence of active cancer disease (87% versus 78%; P <0.001; Supplementary Table S6d, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Mild severity of COVID-19 was indicated for 562 patients (36%), moderate for 822 (53%) and severe for 168 (11%; Table 2).

Complications during COVID-19 illness occurred in 641 patients (39%), most frequently pulmonary (29%), cardiovascular (11%) and systemic (10%; Table 2). Associations of the most common types of complications with cohort demographics, comorbidities and cancer disease characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table S7a-c, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499.

Overall, 609 patients (38%) required supplemental oxygen (Table 2). Treatment for COVID-19 or its sequelae was administered to almost half of the patients (49%), including azithromycin (23%), anticoagulation (23%), hydroxychloroquine (20%) and corticosteroids (16%; Supplementary Table S8, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Regarding the primary endpoint of recovery, of the 1557 patients with available data, 1253 (81%) recovered from COVID-19 (Table 2).

Laboratory measurements and inflammatory-based biomarkers

Laboratory measurements were considered at three distinct timepoints: prior to COVID-19 diagnosis, during COVID-19 and at time of recovery, including white blood cell (×109/l), neutrophil count (×109/l), lymphocyte count (×109/l), platelet count (×109/l), albumin (g/dl), haemoglobin (mmol/l), creatinine (mg/dl), Na (mmol/l) and K (mmol/l) (Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499, indicating differences over the different timepoints). C-reactive protein values were also collected but not included in the analysis, as many extreme values were reported, casting doubt on their validity.

Measurements prior to COVID-19 formed the basis of primary inference, as measurements at this timepoint were feasible for all patients and could also have predictive significance for the COVID-19 disease. Based on these, additional inflammatory-based biomarkers were calculated, according to the OnCovid dataset.18 Two OnCovid inflammatory markers involved C-reactive protein, and thus were not analysed here. NLR, PLR and OIS, measured prior to COVID-19 for ESMO-CoCARE patients, are summarized in Supplementary Table S9, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499.

COVID-19 severity (hospitalization): association with baseline factors

The severity rate of COVID-19 (severe/moderate disease, i.e. hospitalization) differentiated significantly according to each of several factors examined (Supplementary Table S10a, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). The multivariable model is illustrated in Figure 1A. Severe/moderate COVID-19 disease was experienced more frequently in male patients, patients of older age, with worse ECOG PS (≥2), BMI <25 kg/m2 and a higher number of pre-existing comorbidities [odds ratio (OR) = 1.31-2.77]. Regarding cancer characteristics, patients with haematological malignancies developed severe/moderate disease more frequently than patients with solid tumours, as well as patients with progressive disease compared with those with no evidence of disease {OR = 1.91 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.16-3.14] and 1.63 (95% CI 1.08-2.46), respectively}. Symptomatic patients at diagnosis subsequently developed severe/moderate COVID-19 [OR = 10.25 (95% CI 7.08-14.84)] significantly more often. With respect to inflammatory-based biomarkers, patients with NLR ≥6 and patients with OIS ≤40 experienced severe/moderate COVID-19 more frequently [OR = 2.40 (95% CI 1.56-3.69) and 2.51 (95% CI 1.47-4.30), respectively].

Figure 1.

(A) Multivariable logistic model for COVID-19 severity. The model was based on 1533 patients, including 976 patients with hospitalization (severe/moderate COVID-19). (B) Multivariable logistic model for COVID-19 recovery, including only patients with hospitalization (severe/moderate COVID-19 disease). Among patients with available recovery information, 984 needed hospitalization. However, the model was based on 983 hospitalized patients (severe/moderate COVID-19), including 694 recovered patients, because there was 1 patient with missing age.

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NED, no evidence of disease; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; OIS, OnCovid Inflammatory Score; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

aOdds ratios (95% CI) for hospitalized (severe/moderate disease) versus nonhospitalized (mild disease).

bOdds ratios (95% CI) for recovered versus nonrecovered.

cThe ‘not applicable’ category is also included in the ‘unknown/missing’ category.

COVID-19 recovery: association with baseline factors

Recovery from COVID-19 was found to be associated with several risk factors, mostly similar to the ones associated with COVID-19 severity (Supplementary Table S10a, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499 for all patients). In addition, increased recovery rate was found in patients from participating countries in Asia/Oceania, as well as in countries with upper-middle income economies. Among patients with available severity and recovery information, the vast majority (98%) of patients with no need of hospitalization (mild disease) eventually recovered versus a 71% recovery rate among patients with severe/moderate COVID-19 (P <0.001; Supplementary Table S11, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Respective results for the hospitalized patients only are provided in Supplementary Table S10b, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499.

As illustrated in Figure 1B, in the multivariable analysis, focusing on the group of patients who needed hospitalization, the odds of recovering from COVID-19 disease were lower for male patients [OR = 0.52 (95% CI 0.38-0.70)], for older patients [OR = 0.84 (95% CI 0.75-0.94)], with worse ECOG PS [≥2; OR = 0.51 (95% CI 0.37-0.71)] and COVID-19 symptoms [OR = 0.46 (95% CI 0.23-0.92)]. Regarding cancer characteristics, patients with progressive disease compared with patients with no evidence of disease and patients in stage IIII or advanced (IV) stage compared with patients in stage I/II recovered less often [OR = 0.34 (95% CI 0.20-0.59), OR = 0.42 (95% CI 0.21-0.84) and OR = 0.32 (95% CI 0.17-0.61), respectively].

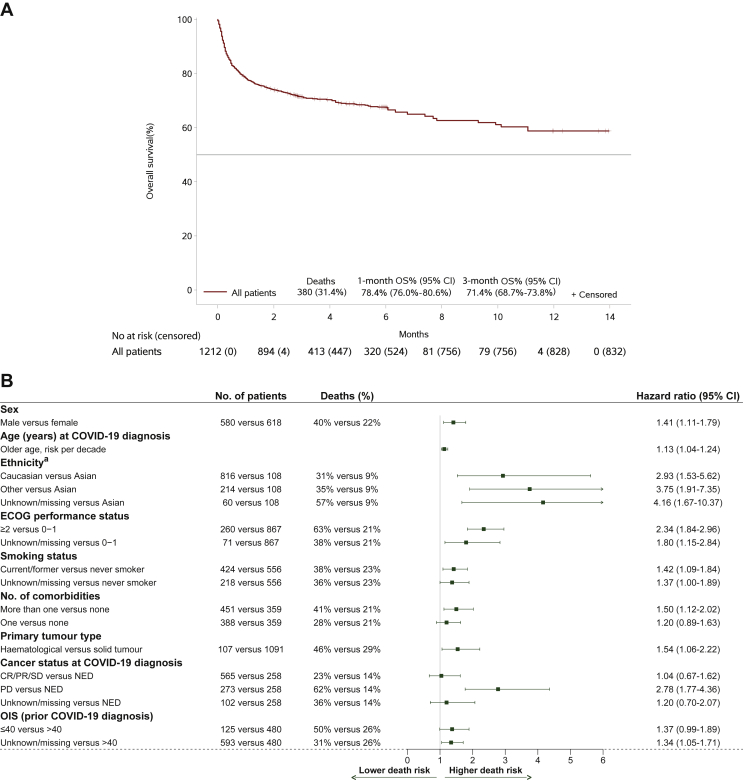

All-cause survival analysis

Based on 1212 patients with follow-up information, the median follow-up time was 3.02 months from COVID-19 diagnosis (interquartile range 2.96-6.05), with 832 (69%) alive patients at last follow-up. Overall, a total of 380 (31%) deaths were recorded, with a 1-month OS rate of 78.4% (95% CI 76.0% to 80.6%) and a 3-month OS rate of 71.4% (95% CI 68.7% to 73.8%). The median OS time was not reached (Figure 2A). From all patients with available follow-up, a total of 297 deaths were reported as related to COVID-19 complications (24.5%); 256 up to 1 month (97.7% of 262 deaths up to 1 month) and 293 up to 3 months (84.7% of 346 deaths up to that timepoint). Hence, from the total of 380 deaths recorded, the majority (78.2%) were attributed to COVID-19 disease, while the remaining 83 deaths were caused by disease progression (12.6%), cancer treatment toxicity (0.3%), other reason (2.1%) or unknown reason (6.8%; Supplementary Tables S12 and S13 available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). As expected, all risk factors significantly associated with COVID-19 recovery also had a significant impact on OS (Supplementary Table S10c, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499).

Figure 2.

(A) Overall survival (n = 1212). Only patients with available follow-up information are included. (B) Multivariable Cox model for overall survival (stratified by cancer stage at COVID-19 diagnosis and symptoms). The model was based on 1198 patients, including 370 deaths. Cancer stage at COVID-19 diagnosis and symptoms were used as stratification factors due to violation of the proportionality hazard assumption.CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NED, no evidence of disease; OIS, OnCovid Inflammatory Score; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

aIn the ‘other’ category: African, Arab/Middle Eastern, Latino American, Mediterranean, Pacific Islander/Māori and others are included. The respective hazard ratio (95% CI) for ‘other’ versus ‘Caucasian’ is 1.28 (0.96-1.69).

In the final multivariable Cox model, a higher mortality risk was estimated for male sex, older age, Caucasian or other ethnicity as compared with Asian, worse ECOG PS, current/former smoking status and pre-existence of comorbidities [hazard risk (HR) ranged from 1.13 for risk per decade of older age to 3.75 for other versus Asian ethnicity].

Regarding cancer characteristics, mortality risk was higher for haematological malignancies compared with solid tumours [HR = 1.54 (95% CI 1.06-2.22)], while an almost threefold increase in risk was found for progressive disease compared with no evidence of disease [HR = 2.78 (95% CI 1.77-4.36)]. With respect to inflammatory-based biomarkers, patients with OIS ≤40 had a higher risk of death, although only at the 10% significance level. Cancer stage at COVID-19 diagnosis and symptoms were included in the model as stratification factors due to detected violation of the proportionality hazard assumption for their effect (explored by the Schoenfeld residuals).

Discussion

Overall, we independently validated previously published observations on variables associated with COVID-19 outcomes in patients with cancer. In addition, Asian ethnicity and higher BMI (≥25 kg/m2) were associated with better COVID-19-related outcomes. Notably, in multivariable analysis most of the factors affecting severity appeared to have a significant impact on OS at 3-month median follow-up.

The COVID-19-related death in our cohort was 24.5%, which is higher than what has been reported for the general population infected with COVID-19.19, 20, 21 In a retrospective case–control analysis from 15 510 patients, the COVID-19-related death for the overall population was 5.61%, compared with 14.93% (100/670) in patients with cancer.20 A meta-analysis from 32 studies and 46 499 patients with COVID-19 (1776 patients with cancer) demonstrated a higher ICU admission (relative risk = 1.56; 95% CI 1.31-1.87) and mortality rate (relative risk = 1.66; 95% CI 1.33-2.07) for patients with cancer in comparison with the noncancer population.21 Interestingly, for patients aged >65 years, the all-cause mortality was comparable between those with cancer versus those without cancer, suggesting the strong effect of age alone for COVID-19-related death.21

The mortality rate associated with COVID-19 for patients with cancer varies in different studies from 13% to 33.6%.16,17,20,22 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, including 33 879 patients with cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection, the overall case fatality rate was 25.4% (95% CI 22.9% to 28.2%), very similar to our findings.23 In another systematic review and meta-analysis from 17 studies, the pooled in-hospital mortality for the 904 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and cancer was 14.1%.24

Those different results might be explained by population heterogeneity and a selection bias towards the most severe cases in some studies. In addition, a higher mortality rate was reported in the beginning of the pandemic.25, 26, 27, 28 Indeed, in our cohort, 38% of cases were diagnosed between March and May 2020. Moreover, the high proportion of cases with advanced or progressive cancer may have influenced the mortality rate observed.

Older age, male sex, current/former smoking (patients exposed to active smoking) status have been consistently associated with worse COVID-19-related outcomes for the general population, irrespective of a cancer diagnosis.29,30 Unsurprisingly similar results were obtained not only in our cohort, but also in other studies in patients with cancer and COVID-19.16,22,26,31 We were intrigued by a significantly lower mortality for the Asian population in our cohort. During the first wave, the pandemic affected more severely Europe than East Asian countries,32,33 reflecting potentially higher social and health system epidemic preparedness in the latter.33 Importantly, the great majority of the Asian population in our cohort is from Asian cancer centres. Beyond clinical characteristics, it has been hypothesized that host genetics and human leukocyte antigen profiles may influence COVID-19 outcomes.34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Notably, a strong correlation was found between ACE1 II genotype, more frequent in Asians, and lower severity or death from COVID-19.39 All these factors may justify the favourable survival from COVID-19 observed in our Asian population, which to the best of our knowledge was not previously reported in other studies on patients with cancer.20,27,40 Nevertheless, considering the low sample size (117 Asians out of 1626 patients), further confirmative analysis in larger populations is needed.

Moreover, in our study, other ethnicities (mainly reported from European centres) tend to have higher, but not statistically significant, mortality rate compared with Caucasians. It has been consistently demonstrated that ethnic minorities in Europe and North America have been more severely affected by COVID-19,41, 42, 43, 44, 45 including patients with cancer.20,27 Social determinants of health, including poorer socioeconomic status, adverse working conditions, decreased access to healthcare or social exclusion may have contributed to these findings.46,47

The following clinical risk factors were associated with worst COVID-19 outcomes in CoCARE: ECOG PS ≥2, pre-existing comorbidities, COVID-19-related symptoms, haematological malignancies and progressive disease. Although collectively these parameters are consistent with those reported in other studies,16,22,31 intriguingly, we observed that overweight/obese patients (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) experienced less often infection requiring hospitalization compared with patients with BMI <25 kg/m2. In other series, obesity has been associated with worse outcomes from COVID-19, in the general population48, 49, 50 and cancer,16 whereas this correlation was not confirmed by others.51 Overweight status has been associated with better survival in patients with advanced cancer.52, 53, 54 This so-called obesity paradox may be justified by increased treatment tolerability and fitness status associated with higher BMI.52 Besides, any correlation between obesity and clinical outcomes may be confounded by tumour characteristics and treatment (i.e. hormonotherapy),52,53 although we found no such association between obesity and confounders in our cohort, except for a higher prevalence of obesity in patients with colorectal and breast cancers (Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100499). Finally, the correlation between BMI and cancer outcomes can be impacted by inaccurate or evolving-over-time BMI measurements. Moreover, adiposity and muscle mass contribute to BMI, are more potent prognosticators and can vary from one patient to another.52,55,56 Further studies are needed to better assess the influence of BMI, muscle mass and adiposity for patients with cancer and COVID-19.

In our multivariable analysis, no significant association was found between current administration of cancer treatment and COVID-19-related outcomes. Although in some studies cytotoxic chemotherapy was associated with worse outcomes,27,57 that was not confirmed in other cohorts.22,31,58 Heterogeneity related to the class of therapies, treatment intention (curative versus noncurative), time between treatment and COVID-19 diagnosis and type of disease may contribute to these apparently contradictory results. Hormonotherapy, targeted therapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been associated with worse outcomes from COVID-19 in recent literature.27,31,57,59

We independently validated NLR ≥6 and OIS ≤40 as prognosticators for COVID-19 severity and OIS ≤40 (at 10% significance level) for OS, following a previous publication by Dettorre et al.60,61 Systemic inflammatory response and several alterations in inflammation-related parameters have been associated with worst COVID-19 outcomes in the overall population18, 62, 63 and also in patients with cancer.27,60,64 The NLR and OIS (or prognostic nutritional index) combine commonly used laboratory parameters (neutrophils, lymphocytes and albumin level), and represent easily accessible, inexpensive and valid scores that can be implemented in daily clinical practice. Among other available prognosticator algorithms, CORONET is a decision-support online tool focused on hospital admissions and recovery of patients with cancer and COVID-19,65,66 which has been updated by integrating the ESMO-CoCARE data.66

There are limitations in our study. This is an observational registry study, with potential selection bias including missing values, the tendency to identify and report mainly the more severe cases, heterogeneity in patient management and data collection across institutions. We observed some differences in type and quality of data collected over time, in line with the increasing clinical experience and knowledge in managing patients with COVID-19. Finally, the quality of data depended on each centre, without the implementation of a centralized audit system. Despite these limitations, a unique electronic case report form and the multicentre, multicountry nature of the study with >1500 cases included empower a robust statistical analysis partly mitigating the selection bias.

In conclusion, in our study, male sex, older age, smokers, non-Asian ethnicity, poor ECOG PS, lower BMI, presence of comorbidities, symptomatic COVID-19, higher NLR, lower OIS, haematological malignancies, more advanced disease stage and progressive cancer status were identified as risk factors for COVID-19 adverse outcomes in patients with cancer. We are now facing another phase of the pandemic with a significant proportion of patients with cancer vaccinated against COVID-19 across countries, many already receiving a vaccination boost and new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern with different transmissibility and morbidity rates. In this rapidly evolving context, ESMO-CoCARE is committed to strengthen a worldwide network tackling unmet needs for people with cancer and COVID-19 with the long-term goal to support clinicians and regulatory bodies on the optimal management of patients with cancer.

Acknowledgements

The ESMO Co-CARE Registry Steering Committee thanks the following for their contribution in the development, monitoring, implementation, support and coordination of the project: Klizia Marinoni and Delanie Young (ESMO Scientific and Medical Division), Isabelle Scherer (ESMO Legal Officer), Vanessa Pavinato (ESMO Communication Head) Keith McGregor (ESMO CEO), Jean-Yves Douillard (former ESMO CMO); Institut Curie in its role of Controller with special mention to the Legal Office Staff Veronique Gillon, Jeremie Tournay and Cécile Bultez (Euraxi). The ESMO Co-CARE Registry Steering Committee expresses its gratitude towards the centres collaborating in the Registry, their principal investigators, the patients and anyone involved in the effort.

Funding

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

Disclosure

MS was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of state support for the creation and development of World-Class Research Centers ‘Digital biodesign and personalized healthcare’ number 075-15-2020-926. DV reports travel, accommodations and expenses from Merk; honoraria for speakers bureau from Servier. RL reports speaker fee Astra Zeneca and institutional funding from BMS. ACr reports consulting or advisory role with Ipsen, Astellas, Pfizer, MSD Oncology Research (funding to self and hospital), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck (only hospital), Astellas, Amgen, Exelixis, Merck KGaA; and travel accommodations from Merck and Servier. SŠ reports honoraria and/or advisory fees from Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Astra Zeneca and Amicus. MR received travel and personal fees from Novartis and Ipsen. TAG reports honoraria and/or advisory fees from IPSEN, Pfizer, Bayer, Sanofi, Janssen, Astellas, Adacap, Eisai, Lilly, Novartis, BMS. TKC reports institutional and personal, paid and unpaid support for research, advisory boards, consultancy and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Aravive, Aveo, Bayer, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Calithera, Circle Pharma, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelixis, GlaxoSmithKline, IQVA, Infinity, Ipsen, Jansen, Kanaph, Lilly, Merck, NiKang, Nuscan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Aventis, Surface Oncology, Takeda, Tempest, Up-To-Date, CME events (PeerView, OncLive, MJH and others), outside the submitted work; institutional patents filed on molecular mutations and immunotherapy response and ctDNA; equity in Tempest, Pionyr, Osel, Nuscan; serves on committees for NCCN, GU Steering Committee and ASCO/ESMO; Medical writing and editorial assistance support may have been funded by communications companies in part; no speaker’s bureau; has mentored several non-United States citizens on research projects with potential funding (in part) from non-United States sources/Foreign components; the institution (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) may have received additional independent funding of drug companies or/and royalties potentially involved in research around the subject matter. TKC is supported in part by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE (2P50CA101942-16) and Program 5P30CA006516-56, the Kohlberg Chair at Harvard Medical School and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham and Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at DFCI. s provided upon request for scope of clinical practice and research. DA reports consultation/advisory role for AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi (Genzyme), Bayer, Terumo, Roche, Hexal, Samsung Bioepis, Pierre Fabre Pharma, CRA International, Ketchum, IQVIA; reports speaker’s engagement from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi (Genzyme), Bayer, Eli Lilly, Terumo, Boston Scientific, Amgen, Roche, Ipsen, Merck (Serono), Samsung Bioepis, Pierre Fabre Pharma, Servier, PharmaCept, PRMA Consulting, Tactics MD LLC, WebMD Health Corp, From Research to Practice, Aptitude Health, art tempi media, ACE Oncology, Imedex, streamitup Germany, MedAhead (Austria), Clinical Care Options (CCO); reports serving as local PI for Bristol Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre Pharma and coordinating PI for OncoLytics; reports grant funding from AbbVie; reports being/been DSMB chair of Sanofi (Genzyme); reports being/been a steering committee member of Roche. KH declares research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, MSD, Replimune and advisory board fees/honoraria from Arch Oncology, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Codiak Biosciences, Inzen Therapeutics, Merck-Serono, MSD, Pfizer, Replimune. OM reports personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Amgen, NeraCare GmbH, outside the submitted work. UD reports honorarium as Member of the Tumor Agnostic Evidence Generation Working Group of Roche, outside the submitted work. GP reports grants from Amgen, Lilly; grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Merck; grants and non-financial support from AstraZeneca; grants and personal fees from Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Novartis, outside the submitted work. SPe reports consultation/advisory role for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Biocartis, Bio Invent, Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, Daiichi Sankyo, Debiopharm, Eli Lilly, Elsevier, F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, Foundation Medicine, Illumina, Incyte, IQVIA, Janssen, Medscape, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Merck Serono, Merrimack, Mirati, Novartis, Pharma Mar, Phosplatin Therapeutics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, Vaccibody; talk in a company’s organized public event for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, e-cancer, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, Illumina, Medscape, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, PER, Pfizer, Prime, RTP, Sanofi, Takeda; receipt of grants/research supports from being a (sub)investigator in trials (institutional financial support for clinical trials) sponsored by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biodesix, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, GSK, Illumina, Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Merck Serono, Mirati, Novartis, and Pfizer, Phosplatin Therapeutics. ER reports investigator-initiated trial (funds paid to the institution) supported by Astra-Zeneca, BMS; serves on the consultancy/advisory board for Astra-Zeneca, Merck, Roche, Pierre Fabre. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolston K.V.I. Infections in cancer patients with solid tumors: a review. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6(1):69–83. doi: 10.1007/s40121-017-0146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zembower T.R. Epidemiology of infections in cancer patients. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;161:43–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04220-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamboj M., Sepkowitz K.A. Nosocomial infections in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(6):589–597. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelo-Branco L., Awada A., Pentheroudakis G., et al. Beyond the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic: opportunities to optimize clinical trial implementation in oncology. ESMO Open. 2021;6(5):100237. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patt D., Gordan L., Diaz M., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: how the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:1059–1071. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards M., Anderson M., Carter P., Ebert B.L., Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(6):565–567. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris E.J.A., Goldacre R., Spata E., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection and management of colorectal cancer in England: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakouny Z., Paciotti M., Schmidt A.L., et al. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):458–460. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curigliano G., Banerjee S., Cervantes A., et al. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(10):1320–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A.J.X., Purshouse K. COVID-19 and cancer registries: learning from the first peak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(11):1777–1784. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01324-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmieri C., Palmer D., Openshaw P.J.M., Baillie J.K., Semple M.G., Turtle L. Cancer datasets and the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: establishing principles for collaboration. ESMO Open. 2020;5(3) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai A., Mohammed T.J., Duma N., et al. COVID-19 and cancer: a review of the registry-based pandemic response. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(12):1882–1890. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carreira H., Strongman H., Peppa M., et al. Prevalence of COVID-19-related risk factors and risk of severe influenza outcomes in cancer survivors: a matched cohort study using linked English electronic health records data. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta V., Goel S., Kabarriti R., et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935–941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castro V.M., McCoy T.H., Perlis R.H. Laboratory findings associated with severe illness and mortality among hospitalized individuals with coronavirus disease 2019 in Eastern Massachusetts. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Eng J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q., Berger N.A., Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220–227. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Siempos Effect of cancer on clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of patient data. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:799–808. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinato D.J., Zambelli A., Aguilar-Company J., et al. Clinical portrait of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in European patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(10):1465–1474. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tagliamento M., Agostinetto E., Bruzzone M., et al. Mortality in adult patients with solid or hematological malignancies and SARS-CoV-2 infection with a specific focus on lung and breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163:103365. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarifkar P., Kamath A., Robinson C., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oncol. 2021;33(3):e180–e191. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinato D.J., Patel M., Lambertini M., et al. 1565MO. Time-dependent improvement in the clinical outcomes from COVID-19 in cancer patients: an updated analysis of the OnCovid registry. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S1132. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mileham K.F., Bruinooge S.S., Aggarwal C., et al. Changes over time in COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients undergoing cancer treatment in the United States: initial report from the ASCO registry. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(4):e426–e441. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grivas P., Khaki A.R., Wise-Draper T.M., et al. Association of clinical factors and recent anticancer therapy with COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer: a report from the COVID-19 and cancer consortium. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(6):787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmieri L., Palmer K., Lo Noce C., et al. Differences in the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients who died in hospital during different phases of the pandemic: national data from Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(1):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01764-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izcovich A., Ragusa M.A., Tortosa F., et al. Prognostic factors for severity and mortality in patients infected with COVID-19: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko J.Y., Danielson M.L., Town M., et al. Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization: COVID-19-associated hospitalization surveillance network and behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(11):e695–e703. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee L.Y., Cazier J.-B., Angelis V., et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1919–1926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lippi G., Mattiuzzi C., Sanchis-Gomar F., Henry B.M. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients dying from COVID-19 in Italy vs China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1759–1760. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto N., Bauer G. Apparent difference in fatalities between Central Europe and East Asia due to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: four hypotheses for possible explanation. Medical Hypotheses. 2020;144:110160. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Migliorini F., Torsiello E., Spiezia F., et al. Association between HLA genotypes and COVID-19 susceptibility, severity and progression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00563-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velavan T.P., Pallerla S.R., Rüter J., et al. Host genetic factors determining COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. EBioMedicine. 2021;72:103629. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellinghaus D., Degenhardt F., Bujanda L., et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niemi M.E.K., Karjalainen J., Liao R.G., et al. Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;600(7889):472–477. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03767-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elhabyan A., Elyaacoub S., Sanad E., Abukhadra A., Elhabyan A., Dinu V. The role of host genetics in susceptibility to severe viral infections in humans and insights into host genetics of severe COVID-19: a systematic review. Virus Res. 2020;289:198163. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto N., Ariumi Y., Nishida N., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 mortalities strongly correlate with ACE1 I/D genotype. Gene. 2020;758:144944. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garassino M.C., Whisenant J.G., Huang L.-C., et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):914–922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mude W., Oguoma V.M., Nyanhanda T., Mwanri L., Njue C. Racial disparities in COVID-19 pandemic cases, hospitalisations, and deaths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11 doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan D., Sze S., Minhas J.S., et al. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100404. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aldridge R.W., Lewer D., Katikireddi S.V., et al. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups in England are at increased risk of death from COVID-19: indirect standardisation of NHS mortality data. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5 doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15922.1. 88-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magesh S., John D., Li W.T., et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marmot R.W.M. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2003. Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paremoer L., Nandi S., Serag H., Baum F. Covid-19 pandemic and the social determinants of health. BMJ. 2021;372:n129. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang J., Hu J., Zhu C. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):257–261. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J., Tian C., Chen Y., Zhu C., Chi H., Li J. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(5):2662–2674. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sjögren L., Stenberg E., Thuccani M., et al. Impact of obesity on intensive care outcomes in patients with COVID-19 in Sweden—a cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ioannou G.N., Locke E., Green P., et al. Risk factors for hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or death among 10 131 US veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lennon H., Sperrin M., Badrick E., Renehan A.G. The obesity paradox in cancer: a review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(9):56. doi: 10.1007/s11912-016-0539-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrelli F., Cortellini A., Indini A., et al. medRxiv; 2020. Obesity paradox in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 6,320,365 patients.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.28.20082800v1 . Available at. Accessed May 14, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simkens L.H.J., Koopman M., Mol L., et al. Influence of body mass index on outcome in advanced colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(17):2560–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee D.H., Giovannucci E.L. The obesity paradox in cancer: epidemiologic insights and perspectives. Curr Nutr Rep. 2019;8(3):175–181. doi: 10.1007/s13668-019-00280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez M.C., Pastore C.A., Orlandi S.P., Heymsfield S.B. Obesity paradox in cancer: new insights provided by body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5):999–1005. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yekedüz E., Utkan G., Ürün Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis: the effect of active cancer treatment on severity of COVID-19. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brar G., Pinheiro L.C., Shusterman M., et al. COVID-19 severity and outcomes in patients with cancer: a matched cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(33):3914–3924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo J., Rizvi H., Egger J.V., Preeshagul I.R., Wolchok J.D., Hellmann M.D. Impact of PD-1 blockade on severity of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancers. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dettorre G., Diamantis N., Loizidou A., et al. 319O. The systemic pro-inflammatory response identifies cancer patients with adverse outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S1366. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dettorre G.M., Dolly S., Loizidou A., et al. Systemic pro-inflammatory response identifies patients with cancer with adverse outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection: the OnCovid Inflammatory Score. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(3) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muiños P.J.A., Otero D.L., Amat-Santos I.J., et al. The COVID-19 lab score: an accurate dynamic tool to predict in-hospital outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):9361. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88679-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee R.J., Wysocki O., Bhogal T., et al. Longitudinal characterisation of haematological and biochemical parameters in cancer patients prior to and during COVID-19 reveals features associated with outcome. ESMO Open. 2021;6(1):100005. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2020.100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee R., Wysocki O., Zhou C., et al. CORONET. COVID-19 risk in oncology evaluation tool. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39 doi: 10.1200/CCI.21.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee R.J., Zhou C., Wysocki O., et al. medRxiv; 2020. Establishment of CORONET; COVID-19 Risk in Oncology Evaluation Tool to identify cancer patients at low versus high risk of severe complications of COVID-19 infection upon presentation to hospital.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.30.20239095v1 . Available at. Accessed May 14, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.