Abstract

COVID pneumonitis can cause patients to become critically ill. They may require intensive care and mechanical ventilation. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a concern. This review discusses VAP in this group. Several reasons have been proposed to explain the elevated rates of VAP in critically ill COVID patients compared to non-COVID patients. Extrinsic factors include understaffing, lack of personal protective equipment and use of immunomodulating agents. Intrinsic factors include severe parenchymal damage and immune dysregulation, along with pulmonary vascular endothelial inflammation and thrombosis. The rate of VAP has been reported at 45.4%, with an intensive care unit mortality rate of 42.7%. Multiple challenges to diagnosis exist. Other conditions such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary oedema and atelectasis can present with similar features. Frequent growth of gram-negative bacteria has been shown in multiple studies, with particularly high rates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The rate of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis has been reported at 4–30%. We would recommend the use of invasive techniques when possible. This will enable de-escalation of antibiotics as soon as possible, decreasing overuse. It is also important to keep other possible causes of VAP in mind, e.g. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis or cytomegalovirus. Diagnostic tests such as galactomannan and β-D-glucan should be considered. These patients may face a long treatment course, with risk of re-infection, along with prolonged weaning, which carries its own long-term consequences.

Short abstract

Critically ill COVID-19 patients are at risk of developing VAP for several reasons. This increases their overall mortality. Although challenging, early identification of the causative organism through invasive techniques is advised. https://bit.ly/3vCatYv

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken the world by storm. Intensive care units (ICU) across the globe have been put under extreme pressure. Although the global COVID-19 pandemic has lasted over 2 years at the time of writing, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (pneumonia that occurs 48 h post intubation or longer [1]) is still posing a challenge to intensive care clinicians now. The estimated mortality rate of VAP in COVID patients is 42.7% [1]. An increase in the number of patients requiring intensive care has been shown. These patients go on to require invasive ventilation with prolonged ICU stays. As a result, these patients are at substantial risk of developing VAP.

This review discusses the topic of VAP in adult patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. The risk factors, prevalence, diagnostic challenges and aetiology will be detailed. Prevention, treatment and stewardship will be examined. Weaning, re-infection and long-term outcomes of VAP in critically ill COVID patients will be discussed.

Using the terms “ventilator-associated pneumonia”, “VAP”, “COVID” and “ICU”, a search was carried out to identify suitable publications to include in this review. The following databases were used: PubMed, Embase, Annual Reviews, Biomedical Central Journals Complete, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Database and JAMA Network. Only articles written in English were included. This is intended to be a narrative review, it is not a meta-analysis.

Why do COVID patients develop VAP?

The risk of developing nosocomial infections in critically ill COVID patients is multifactorial. In terms of extrinsic factors, it has been proposed that a lack of adequate staffing and personal protective equipment (PPE) at the beginning of the pandemic may have led to an increased rate of cross-contamination between patients, leading to higher rates of VAP in COVID patients compared with non-COVID patients [2, 3]. COVID patients are also mechanically ventilated for longer and are more likely to require prone positioning than non-COVID patients. It has been reported in some studies that this group of patients are placed in the prone position twice as frequently as influenza patients [4, 5]. Although prone positioning may increase drainage of oral secretions, it has not been shown to reduce VAP [6]. The addition of immunomodulating agents such as corticosteroids, interleukin-6 (IL-6) antagonists and janus kinase inhibitors [7] may further increase the risk of infection.

The RECOVERY trial demonstrated that corticosteroids decreased the length of mechanical ventilation [8]. Although corticosteroids are sometimes described as a risk factor for VAP, the CoDEX trial displayed a similar reduction in length of mechanical ventilation, with no increase in the rate of VAP [9]. Gragueb-Chatti et al. [10] demonstrated no increase in VAP or bloodstream infection in a multicentre study.

IL-6 antagonists are also postulated to create an immunosuppressive state. Yet, some benefits have been shown for these agents before intubation: they may decrease the need for intubation and decrease mortality. Further research in this area is required [11]. Likewise, janus kinase inhibitors may create an immunosuppressive state, but could also be beneficial in reducing mortality if given in the initial 1–2 weeks of infection. Again, further studies are needed [7]. At present, we can speculate that these drugs may cause immunosuppression and potentially lead to increased rates of VAP.

Grasselli et al. [12] demonstrated that COVID patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) had a rate of VAP of 35%. This was related to a longer duration of stay in the ICU and a higher mortality rate. Luyt et al. [13] showed that COVID patients on ECMO had higher rates of VAP compared to influenza patients on ECMO, although the overall rate of bacterial co-infection was higher in the influenza population.

In terms of intrinsic factors, COVID patients have more severe parenchymal damage and poorer lung compliance compared with non-COVID patients, both of which are risk factors for VAP [14]. It is hypothesised that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause an element of immunoparalysis [15], along with immune dysregulation, resulting in hyperinflammation and issues with lymphoid function [16–18]. One study showed that COVID patients who went on to develop VAP had a detectable change in their lung microbiome several weeks before [19], with a decrease in their antibacterial immune defence. De Pascale et al. [20] found that the lung microbiome in COVID-19 patients who developed Staphylococcus aureus VAP was significantly different from that in non-COVID patients. They found lower bacterial diversity, with S. aureus, Streptococcus anginosus and Olsenella making up the dominant growth. It is theorised that SARS-CoV-2 infection may also cause pulmonary vascular endothelial inflammation and subsequent thrombosis [21–25]. These factors combined create an environment suitable for bacterial growth.

In summary, extrinsic factors include staff shortages, lack of PPE [7], treatment with immunomodulating agents [6, 10, 11] and ECMO [7, 12]. These may account for the increased rate of VAP in critically ill COVID patients compared to non-COVID patients. The effect of steroids is controversial and has been shown in some studies to yield improved outcomes [8, 9]. Intrinsic factors relating to the disease process itself include lung parenchymal damage, poor compliance [13], immune dysregulation [14–18], alterations in the lung microbiome [19] and increased risk of thrombosis [20–24], all of which may play a role in creating a suitable environment for bacterial growth. All risk factors considered, VAP is a serious complication of COVID pneumonitis. It is associated with shock, bacteraemia and polymicrobial infections [26]. Therefore, it still poses challenges to clinicians [27].

Prevalence

A meta-analysis in May 2021 found that the rate of VAP was elevated in COVID patients compared to non-COVID patients [3]. The rate of VAP was 45.4%, with a range of 7.6–86%. These differences in rate of VAP may be attributable to differences in clinical settings, staffing, patient factors (such as reason for ICU admission and disease severity) and the diagnostic criteria for VAP used in each study. The ICU mortality rate was 42.7% in critically ill COVID patients, but this was not necessarily attributable to VAP. The mean ICU length of stay (LOS) was 28.58 days. The authors of the meta-analysis did highlight slight variations in the definition of VAP in the different retrospective studies used, which can pose difficulty when comparing different studies.

Fumagalli et al. [3] described a rate of VAP of ∼50%, with a range of 21–64%. The first episode of VAP was usually detected between days 8 and 12 of invasive ventilation. The mean length of mechanical ventilation was 12–30 days. ICU mortality of COVID patients with VAP was similar to that of non-COVID patients with VAP, at ∼40–55% [28, 29]. This is in keeping with the findings of Fumagalli et al. [3].

Jain et al. [30] described the rate of VAP in COVID patients as 48.15%, with a mortality rate of 51.4%. COVID patients had an overall increased risk of VAP compared to non-COVID patients. Male patients had an increased risk of VAP [30]. Blonz et al. [31] showed a rate of VAP of 48.9%, with a recurrence rate of 19.7%. VAP has been shown to occur late in mechanical ventilation [31–33]. Nseir et al. [29] described an association between VAP and an increased 28-day mortality in COVID patients. Yet, this was not any higher than in patients with influenza or intubated for a non-viral reason.

Challenges of diagnosis

It is important to note that some controversy does exist around the diagnosis of VAP. Sampling methods may vary depending on region [27]. An element of subjectivity regarding diagnosis may also be involved [3]. If a patient's specimen is cultured and fails to grow any microbe, that patient may not be recorded in many studies as having VAP. Should a patient not have any cultures sent owing to other reasons, they too will not be recorded as having VAP. Many of the clinical signs that would indicate VAP are also shared with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), atelectasis and pulmonary oedema. The administration of steroids or ECMO may mask a fever [2]. The Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score has been proposed to predict VAP. It considers temperature, leukocyte count, tracheal secretions, arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction ratio, imaging and cultures [34]. However, it is not currently included in the most recent guidelines on treatment of VAP because of the risk of antibiotic overuse [35].

There is conflicting evidence in relation to the use of invasive versus noninvasive diagnostic procedures. Invasive diagnostic strategies, such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), have been shown to reduce mortality, identify organ failure earlier and reduce the overuse of antibiotics when compared to noninvasive strategies [36]. Yet, no significant differences in patient outcomes were shown when invasive versus noninvasive diagnostic strategies were compared in a meta-analysis in 2014 [37]. It is important to note that invasive or distal strategies include BAL, protected specimen brush and lung biopsy. Blind mini-BAL is not always guaranteed to obtain a distal sample and is classified as a noninvasive strategy [35].

In critically ill COVID patients, performing BAL poses its own risks. This cohort of patients may display poor oxygenation and poor compliance due to ARDS. There is also a risk of viral transmission. One study showed a decrease in the use of BAL from 60% to 25% due to the pandemic [38]. Despite the aforementioned risks associated with invasive sampling, we would recommend the use of invasive techniques when possible. It is important to keep both patient and staff safety in mind. This will enable de-escalation of antibiotics as soon as possible, decreasing overuse.

C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin and soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (sTREM-1) are some of the biomarkers that may be useful in the diagnosis of VAP in all patients. Further studies are required [39–42]. Clinical assessment is still regarded as paramount. The use of routine monitoring of a specific biomarker is not recommended [43, 44].

In patients receiving an IL-6 inhibitor, CRP levels may not be an accurate marker. IL-6 is involved in the stimulation of CRP synthesis from hepatocytes [45, 46]. Initial studies demonstrated a low procalcitonin level in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection alone [47, 48]; however, elevated procalcitonin has also been shown in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [49]. Viral infection may also interfere with interferon-γ release, and this may cause an inaccurate procalcitonin level [50]. Rouzé et al. [51] demonstrated slightly elevated procalcitonin in patients with bacterial co-infection versus patients without, although not as elevated as in influenza patients with co-infection. In diagnosis, procalcitonin has been described as a promising tool, requiring further evaluation [52, 53].

In summary, biomarkers such as CRP and procalcitonin show promise but require further research. Our recommendations are to use these biomarkers as adjuncts to diagnosis. Clinical context is essential, and they should not be used in place of clinical acumen.

Aetiology

Bacterial

A meta-analysis by Ippolito et al. [4] demonstrated that the main bacteria grown in VAP mostly comprised the gram-negative bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp. and Escherichia coli, along with the gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and Enterococcus faecium. This is in keeping with previous descriptions [3]. Fumagalli et al. [3] described how >50% of bacteria grown were gram negative. Blonz et al. [31] demonstrated that Enterobacteriae accounted for half of the microbiological growth and Pseudomonas accounted for 15.1%. Papazian et al. [35] described how the microorganisms responsible for VAP can vary depending on multiple factors. These include the length of hospital and ICU stay, length of mechanical ventilation, local bacterial strains and exposure to antimicrobial drugs. The bacteria that are usually isolated may not be related to intubation; they are related to the severity of underlying disease [3]. Increased use of empirical antibiotics due to the COVID-19 pandemic poses a threat of increased multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) in the future, and we will discuss this later in the review [54].

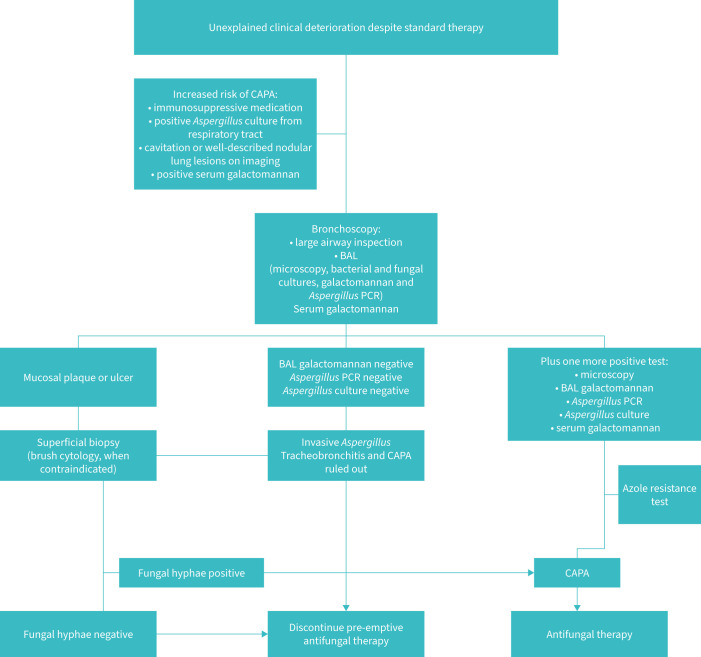

COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

In comparison to bacteria, Aspergillus is rarely the causative agent of VAP in non-COVID patients, except for in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for influenza, or in the immunocompromised. Rouzé et al. [55] demonstrated a lower incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in COVID patients than in influenza patients (4.1% versus 10.2%, respectively). This may be due to the increased proportion of immunosuppressed patients recorded in the influenza group, although this was adjusted for. BAL was performed less frequently in the COVID group owing to the risk of viral transmission, which may have led to under-recognition of aspergillosis. Finally, the authors concluded that the mechanism of entry into the lower respiratory tract and pulmonary lesions related to SARS-CoV-2 and influenza are different. This may account for the different rates of IPA [55]. Aspergillus infection may be under-diagnosed because of delays in diagnosis or a lack of recognition [56]. IPA has become more prevalent as a cause of VAP in COVID patients versus non-COVID patients in general [3]. Fumagalli et al. [3] reported an incidence of COVID-19-associated IPA of 4–30%. This is higher than in the non-COVID population, but further data are required. One multicentre study in the UK reported that aspergillosis may be under-diagnosed in critically ill non-COVID non-neutropenic patients. Up to 20% of VAP may in fact be IPA. The authors of that study advised clinicians to practise a high level of suspicion, and to use galactomannan whenever these patients undergo BAL [57]. They also advised clinicians to acquire distal samples for culture, along with consecutive serum galactomannan indices. Galactomannan from BAL fluid has shown promising results in the early identification and exclusion of COVID-19-associated IPA, but it must currently be used as an adjunct to the clinical picture. Galactomannan from endotracheal aspirate samples is yet to be validated [58]. β-D-glucan has been shown to support the diagnosis of COVID-19-associated IPA [59–61]. Again, this must be used in conjunction with the clinical context. Two or more positive results have a greater diagnostic ability. Real-time PCR for Aspergillus DNA supports the diagnosis [59, 60]. A lateral flow device provides an incredibly quick method of detection of the Aspergillus antigen [61]. Increased length of mechanical ventilation and steroid use increase the risk of Aspergillus infection [62]. To treat IPA, current guidelines recommend the use of a triazole (voriconazole or isavuconazole) initially [29, 63]. Diagnosis and treatment is outlined in figure 1 [61]. A phase 4 trial looking at the use of prophylactic posaconazole for influenza patients is ongoing, although no results are available yet (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03378479). Three other antifungals are currently undergoing trials: ibrexafungerp (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03059992), olorofim (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03583164) and fosmanogepix (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04240886). Hopefully, these new medications can provide other treatment options in the future. It is important to note that antifungal resistance (triazole resistance) is increasing. Therefore, techniques to identify these resistant strains may be crucial for the choice of antifungal treatment, and for epidemiological data [29]. Candida has still not been identified as a VAP-causing agent at this point [64].

FIGURE 1.

Management of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) (adapted from Verweij et al. [61]). BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage.

Viral

Viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus and influenza, among others, can cause VAP [65, 66]. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus can cause reactivation pneumonia in immunocompromised patients [67]. Some studies have shown a benefit to treating viral reactivations with antivirals but further research is required [36]. Meyer et al. [68] showed that HSV reactivation in COVID patients is associated with increased 60-day mortality. Of the 153 critically ill COVID patients included in the study, they found a reactivation rate of 26.1%.

Other agents

No reports of VAP caused by atypical bacteria were identified in our search. It appears that atypical bacteria are not a frequent cause of co-infection in COVID patients, and even less so a cause of VAP. Streptococcus pneumoniae is rarely seen. Yet, they should still be considered within the clinical context of each patient [52–54]. Tuberculosis (TB) is not a common cause of VAP and is more likely to have been present before SARS-CoV-2 infection. TB patients are at higher risk of COVID infection, with a higher mortality rate [69]. Our search found no cases of VAP caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria. However, two cases of co-infection with mycobacteria in COVID patients were described in the literature (M. simiae [70] and M. abscessus [71]).

Prevention and infection control

From a nursing standpoint, good preventative measures are crucial in all intubated patients (COVID and non-COVID) [72]. Elevation of the head of the bed, draining of subglottic secretions and maintenance of endotracheal cuff pressure all decrease the risk of aspiration. Avoiding prolonged mechanical ventilation can be achieved by appropriate weaning. Daily interrupted sedation has been shown to decrease rates of VAP [73]. It is thought that this is secondary to an improved respiratory function and gag reflex. Daily evaluation for extubation should also be carried out. An effort should be made to reduce the pathogen load. Different techniques such as regular tooth brushing and chlorhexidine mouthwash have also been shown to decrease rates of VAP [74]. Early enteral feeding within 48 h can reduce the rate of translocation of intestinal bacteria to the lungs [75]. Conversely, routine circuit changes have been shown to increase rates of VAP [76]. Suction of the endotracheal tube should be performed only when necessary and with good technique, yet subglottic suctioning has been described as under-utilised and is recommended in COVID patients receiving mechanical ventilation [77]. Two studies based in the non-intensive care setting have shown decreased rates of VAP with brief intubations during theatre. Nam et al. [78] reported a 600% decrease in postoperative VAP in cardiac patients who underwent routine subglottic suctioning and Yuzkat and Demir [79] showed decreased rates of VAP post rhinoplasty surgery. We could not find any literature comparing these preventative measures on the development of VAP between COVID and non-COVID patients. Sakano et al. [80] advise that the most up-to-date evidence must continue to be incorporated into ICU care bundles (as discussed in this paragraph). They make the solid point that the best way to avoid VAP is to avoid intubation in the first place.

The above-mentioned practices can be incorporated into care bundles aimed specifically at reducing rates of VAP [81]. These practices can be applied to all ventilated patients. In terms of nursing ventilated COVID patients specifically, the following recommendations have been made: oral intubation is preferred over nasal, a closed suctioning system should be used to drain and discard condensation, head of bed elevation should be in place, a new circuit should be used with each patient and only changed when necessary, and heat and moisture exchanger filters should only be changed every 5–7 days or when soiled [82]. Owing to the challenges mentioned previously regarding the diagnosis of VAP, one cannot say with complete certainty if these preventative measures reduce the rate of VAP. The definition of VAP in different studies may vary [83].

Adequate staffing has also been shown to be essential. The nurse-to-patient ratio has been suggested as a good indicator for the level of staffing. This not only helps to decrease pathogen spread, but also benefits adequate diagnosis and treatment of VAP [84, 85]. It is important to note that many ICUs around the world expanded outside their original setting because of the sudden high demand for ICU beds. Therefore, many critically ill patients received care outside of ICU. These patients showed elevated mortality [86].

Infection control plays a key role when treating COVID patients. We would advise specific antimicrobial surveillance studies for the ICU [55, 87]. Diagnostic tests should be carried out when infection is suspected, not pre-emptively. Patients should be cared for in separate rooms [81]. It has been advised that healthcare workers wear full PPE, including visor and N95 facemasks, when caring for patients. All healthcare staff involved should be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2. At present, it is not advised to routinely test staff for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Basic hand hygiene, infection control surveillance, disinfection of clinical areas and separation of waste have all been advised [81]. Antimicrobial stewardship remains a key feature, as with non-COVID patients. The aim is to not only prevent viral transmission of COVID, but also reduce the spread of other pathogens and MDROs [88].

Treatment

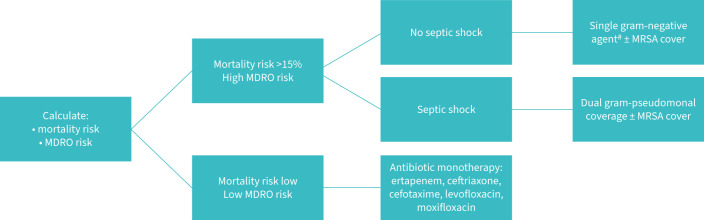

The initial empirical cover advised for VAP is summarised in figure 2 [89–91].

FIGURE 2.

Advised empiric cover for ventilator-associated pneumonia (adapted from Torres et al. [91). MDRO: multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Studies have reported a mean ICU mortality for COVID patients who develop VAP of 42.7% [2], but the exact attributable mortality is unknown. It is important to treat each individual patient within their own clinical context.

The efficacy and appropriateness of novel antibiotics against resistant gram-negative bacteria has been summarised by Garduno et al. [92].

The efficacy of nebulised antibiotics has not yet been demonstrated [93, 94]. Many patients have concomitant bloodstream infections for which nebulised antibiotics alone would be inappropriate [95]. Apart from colistin, no significant increase in efficacy has been shown when nebulised antibiotics are used as an adjunct to the intravenous route [54, 96–98].

Stewardship

Risk factors for MDROs include previous colonisation, ARDS occurring before VAP, septic shock and acute renal replacement therapy before VAP [4]. Increased use of empirical antibiotics owing to the COVID-19 pandemic poses a threat of increased MDROs in the future [87]. Enterobacteriaceae resistant to cephalosporins have become more common, with resistance due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase and AmpC B-lactamase expression [99]. Carbapenemase expression is also worrying. P. aeruginosa strains that are multidrug resistant are also becoming more frequently detected [100]. 50–67% of A. baumannii strains grown from VAP are carbapenem resistant [101]. Critically ill COVID patients are at increased risk of MDROs, and this can significantly influence outcome [102]. One study performed in a single centre found that ∼77% of K. pneumoniae cultured from COVID patients in the ICU demonstrated multidrug resistance [103].

Some guidelines do not recommend administering antibiotics to patients who have a negative culture and are clinically stable [4]. Exposing patients to fewer unnecessary antibiotics should decrease the risk of bacterial imbalance, which leads to infections such as Clostridium difficile. It should also decrease the development of MDROs. However, it is ultimately the clinician's decision whether the patient is at risk of deterioration, and if antibiotics should be commenced [4]. Administering antibiotics before sampling can yield a false-negative result. Papazian et al. [35] recommend re-evaluating every 48–72 h, using the clinical course to decide when to stop antibiotics. This is in relation to VAP in all patients [35]. They also describe the use of decreasing procalcitonin to stop antibiotics. A procalcitonin concentration <0.5 ng·mL−1 or that has reduced by 80% from its peak at 48–72 h may indicate that it is appropriate to stop antibiotics [104, 105], but clinical judgement should still be used. As previously discussed, we would not recommend reliance on procalcitonin alone, and further research is required in this area. At present, it takes anywhere from 24 h to 48 h to culture bacteria. Broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics are required during this time. Ideally, patients should only receive broad-spectrum antibiotics for as short a duration as possible. Therapy should be targeted based on cultures, which should decrease the growth of MDROs. Methods such as PCR can identify bacteria and resistant strains quicker but must be requested for specific pathogens. One example is mecA to detect methicillin-resistant S. aureus [106]. There is a new diagnostic tool called the Unyvero system that can identify the most common causative agents of VAP (20 bacteria and one fungus). It can also detect 19 markers of resistance. Results are available within 4–5 h. However, at present, Unyvero may over-detect; it can detect commensals, non-viable bacteria and pathogenic bacteria that have not reached pathogenic thresholds, which may lead to the overuse of antibiotics. Although this technique does require further refinement, it does pose a potential improvement in VAP diagnosis in the future [107–110].

Antibiotic overtreatment could be a risk factor for developing VAP in COVID patients. An imbalance in the body's natural flora can occur as a result. In the early days of the pandemic, azithromycin was thought to have some antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2. This has now been disproven and azithromycin is not recommended as empirical treatment anymore. Despite this, Blonz et al. [31] did find that the risk of polymicrobial VAP was reduced with the initiation of empirical antibiotics. At present, empirical antibiotics are not routinely recommended for COVID patients without any evidence of bacterial infection because this may lead to overuse, along with the development of MDROs [111]. Combination therapy is advised when treating VAP, except for patients in the early stages of VAP or without risk of MDROs. Therapy should be targeted based on cultures and is usually recommended for 7 days [35]. Karolyi et al. [112] performed a study that showed how the results of a multiplex PCR were consistent with microbiological cultures. This could provide earlier bacterial identification in the future. They concluded that diagnosis could be made more easily if both techniques are used together.

Weaning and re-infection

Unsuccessful weaning has been associated with poorer outcomes. Elevated peak plateau pressures may increase the risk of unsuccessful weaning, whereas higher compliance and lower driving pressures may reduce the risk. Positive end expiratory pressure, partial pressure of carbon dioxide and arterial oxygen tension:inspiratory oxygen fraction ratio appear to have no significant bearing on whether a patient is weaned successfully or not [113]. Protective mechanical ventilation is advised [114]. One article showed that patients extubated within 2 weeks had no pathogenic growth; however, these patients may only have been extubated because they did not develop VAP [115]. Tracheostomy placement is safe and beneficial in this group of patients [116–119], although a higher rate of tracheomalacia has been reported (5%) [120]. Tracheostomy has been shown to improve ICU capacity [121]. Although no difference has been shown between early and late tracheostomy insertion in terms of mortality [122], earlier tracheostomy placement has better overall outcomes [123]. There may be a benefit in preserving muscle mass [124].

Although Blonz et al. [31] showed a recurrence rate of 19.7%, another study reported re-infection rates of 43% in critically ill COVID patients, which did influence prognosis. The authors suggest that hospital overburden at the start of the pandemic could have been responsible for this [125]. Immune dysregulation could also be a factor [126]. MDROs are frequently seen in re-infection. Re-infection is associated with length of mechanical ventilation and ICU LOS. Early diagnosis plays a key role in identifying MDROs early, commencing adequate treatment and improving outcomes [127].

Long-term issues

There is a high mortality rate in critically ill COVID patients 3 months post hospital discharge [128], with ongoing symptoms found in two thirds of patients discharged and 10% of these requiring home oxygen. However, hospital readmission rates in these patients were still low. Persistent symptoms were associated with the following independent risk factors: female gender, ICU LOS, ICU-acquired pneumonia and ARDS. Of these, ICU-acquired pneumonia prevention could yield a potential reduction in mortality post discharge [91].

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested ICUs globally. For several reasons, COVID patients are at high risk of developing VAP. Although the diagnosis of VAP remains controversial, and can vary from study to study, an elevated incidence has been shown in COVID patients. A review of major studies suggested a rate of VAP between 7.6% and 86% [3]. The ICU mortality rate was 42.7% (not necessarily attributable to VAP) [1]. The mean ICU LOS was 28.58 days. Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas (15.1%), along with the gram-positive S. aureus, were the most common organisms grown [3]. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis was reported in 4–30% [2]. Viruses were even less common. Atypical bacteria and TB were not reported as a cause of VAP. Preventative measures can be implemented through care bundles, and this may lead to a reduction in VAP. Treatment is recommended to begin with a broad empirical cover but this should be targeted based on microbial growth as soon as possible. MDROs are already increasing in frequency, and antibiotic stewardship will continue to play an essential role. Biomarkers such as procalcitonin show potential, but still require further evaluation. Drugs commonly used in the treatment of COVID patients, such as dexamethasone, tocilizumab and janus kinase inhibitors, considerably reduce CRP and procalcitonin. This causes another challenge in diagnosis [47]. New methods of early identification of microbes along with certain resistance patterns could result in improved diagnosis and treatment in the future. Ongoing trials of new medications and techniques are yet to display any positive findings. Although our knowledge of this disease process is ever expanding, we still hold a pessimistic view for this group of patients. We would recommend the use of invasive techniques when possible. This will enable de-escalation of antibiotics as soon as possible, decreasing overuse. It is important to diagnose other possible causes of VAP, e.g. COVID-19-associated IPA and cytomegalovirus. Other diagnostic tests such as galactomannan and β-D-glucan should also be used.

Footnotes

Provenance: Commissioned article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kalanuria AA, Zai W, Mirski M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU. Crit Care 2014; 18: 208. doi: 10.1186/cc13775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ippolito M, Ramanan M, Bellina D, et al. Personal protective equipment use by healthcare workers in intensive care unit during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a secondary analysis of the PPE-SAFE survey. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2021; 8: 2049936121998562. doi: 10.1177/2049936121998562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fumagalli J, Panigada M, Klompas M, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia among SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 2022; 28: 74–82. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ippolito M, Misseri G, Catalisano G, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; 10: 545. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63: e61–e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayzac L, Girard R, Baboi L, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in ARDS patients: the impact of prone positioning. A secondary analysis of the PROSEVA trial. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42: 871–878. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4167-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limen RY, Sedono R, Sugiarto A, et al. Janus kinase (JAK)-inhibitors and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022; 20: 425–434. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1982695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gragueb-Chatti I, Lopez A, Hamidi D, et al. Impact of dexamethasone on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and blood stream infections in COVID-19 patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation: a multicenter retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care 2021; 11: 87. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00876-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group , Shankar-Hari M, Vale CL, Godolphin PJ, et al. Association between administration of IL-6 antagonists and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2021; 26: 499–518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Di Bella S, et al. Nosocomial infections during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: incidence, etiology, and impact on patients’ outcome. Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 1726–1733. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luyt CE, Sahnoun T, Gautier M, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring ECMO: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care 2020; 10: 158. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00775-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moretti M, Van Laethem J, Minini A, et al. Ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia in coronavirus 2019 disease, a retrospective monocentric cohort study. J Infect Chemother 2021; 27: 826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science 2020; 368: 473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Z, Ren L, Zhang L, et al. Heightened innate immune responses in the respiratory tract of COVID-19 patients. Cell Host Microbe 2020; 27: 883–890. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, et al. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe 2020; 27: 992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luyt CE, Bouadma L, Morris AC, et al. Pulmonary infections complicating ARDS. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 2168–2183. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06292-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsitsiklis A, Zha BS, Byrne A, et al. Impaired antibacterial immune signaling and changes in the lung microbiome precede secondary bacterial pneumonia in COVID-19. medRxiv 2021; preprint [ 10.1101/2021.03.23.21253487]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Pascale G, De Maio F, Carelli S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with COVID-19: clinical features and potential inference with lung dysbiosis. Crit Care 2021; 25: 197. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03623-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leisman DE, Deutschman CS, Legrand M. Facing COVID-19 in the ICU: vascular dysfunction, thrombosis, and dysregulated inflammation. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1105–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06059-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wicky PH, Niedermann MS, Timsit JF. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: how common and what is the impact? Crit Care 2021; 25: 153. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03571-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell JS, Peyvandi F, Martin-Loeches I. Pulmonary immuno-thrombosis in COVID-19 ARDS pathogenesis. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47: 899–902. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06419-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouyer M, Strazzulla A, Youbong T, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; 10: 988. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giacobbe DR, Battaglini D, Enrile EM, et al. Incidence and prognosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter study. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 555. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chastre J, Trouillet JL, Vuagnat A, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1165–1172. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9708057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nseir S, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, et al. Relationship between ventilator-associated pneumonia and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a planned ancillary analysis of the coVAPid cohort. Crit Care 2021; 25: 177. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03588-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain S, Khanna P, Sarkar S. Comparative evaluation of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill COVID- 19 and patients infected with other corona viruses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2021; 92: 1610. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2021.1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blonz G, Kouatchet A, Chudeau N, et al. Epidemiology and microbiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia in COVID-19 patients: a multicenter retrospective study in 188 patients in an un-inundated French region. Crit Care 2021; 25: 72. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03493-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care 2021; 25: 25. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esperatti M, Ferrer M, Theessen A, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in the intensive care unit acquired by mechanically ventilated versus nonventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 1533–1539. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0094OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schurink CAM, Nieuwenhoven CAV, Jacobs JA, et al. Clinical pulmonary infection score for ventilator-associated pneumonia: accuracy and inter-observer variability. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt CE. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 888–906. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05980-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fagon JY, Chastre J, Wolff M, et al. Invasive and noninvasive strategies for management of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 621–630. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berton DC, Kalil AC, Teixeira PJ. Quantitative versus qualitative cultures of respiratory secretions for clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 10: CD006482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006482.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wahidi MM, Shojaee S, Lamb CR, et al. The use of bronchoscopy during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: CHEST/AABIP guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2020; 158: 1268–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibot S, Cravoisy A, Levy B, et al. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells and the diagnosis of pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 451–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luyt CE, Combes A, Reynaud C, et al. Usefulness of procalcitonin for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 1434–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1112-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Póvoa P, Martin-Loeches I, Ramirez P, et al. Biomarker kinetics in the prediction of VAP diagnosis: results from the BioVAP study. Ann Intensive Care 2016; 6: 32. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0134-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salluh JIF, Souza-Dantas VC, Póvoa P. The current status of biomarkers for the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonias. Curr Opin Crit Care 2017; 23: 391–397. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Loeches I, Rodriguez A, Torres A. New guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia/ventilator-associated pneumonia: USA vs. Europe. Curr Opin Crit Care 2018; 24: 347–352. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palazzo SJ, Simpson T, Schnapp L. Biomarkers for ventilator-associated pneumonia: review of the literature. Heart Lung 2011; 40: 293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bermudez EA, Rifai N, Buring J, et al. Interrelationships among circulating interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002; 22: 1668–1673. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000029781.31325.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kooistra EJ, van Berkel M, van Kempen NF, et al. Dexamethasone and tocilizumab treatment considerably reduces the value of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin to detect secondary bacterial infections in COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2021; 25: 281. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03717-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020; 323: 1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heer RS, Mandal AK, Kho J, et al. Elevated procalcitonin concentrations in severe COVID-19 may not reflect bacterial co-infection. Ann Clin Biochem 2021; 58: 520–527. doi: 10.1177/00045632211022380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilbert DN. Use of plasma procalcitonin levels as an adjunct to clinical microbiology. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 2325–2329. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00655-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rouze A, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, et al. Early bacterial identification among intubated patients with COVID-19 or influenza pneumonia: a European multicenter comparative cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 204: 546–556. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0030OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richards O, Pallmann P, King C, et al. Procalcitonin increase is associated with the development of critical care-acquired infections in COVID-19 ARDS. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021; 10: 1425. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10111425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Côrtes MF, de Almeida BL, Espinoza E, et al. Procalcitonin as a biomarker for ventilator associated pneumonia in COVID-19 patients: is it an useful stewardship tool? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021; 101: 115344. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cantón R, Gijón D, Ruiz-Garbajosa P. Antimicrobial resistance in ICUs: an update in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Crit Care 2020; 26: 433–441. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rouzé A, Lemaitre E, Martin-Loeches I, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among intubated patients with SARS-CoV-2 or influenza pneumonia: a European multicenter comparative cohort study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 11. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03874-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohamed A, Rogers TR, Talento AF. COVID-19 associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. J Fungi (Basel) 2020; 6: 115. doi: 10.3390/jof6030115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loughlin L, Hellyer TP, White PL, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia in UK ICUs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 1125–1132. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0355OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, et al. Galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: a tool for diagnosing aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 27–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-606OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: 1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Talento AF, Dunne K, Joyce EA, et al. A prospective study of fungal biomarkers to improve management of invasive fungal diseases in a mixed specialty critical care unit. J Crit Care 2017; 40: 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verweij PE, Brüggemann RJM, Azoulay E, et al. Taskforce report on the diagnosis and clinical management of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47: 819–834. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06449-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2020; 63: 528–534. doi: 10.1111/myc.13096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63: e1–e60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fàbregas N, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, et al. Histopathologic and microbiologic aspects of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Anesthesiology 1996; 84: 760–771. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199604000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loubet P, Voiriot G, Houhou-Fidouh N, et al. Impact of respiratory viruses in hospital-acquired pneumonia in the intensive care unit: a single-center retrospective study. J Clin Virol 2017; 91: 52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Someren Gréve F, Juffermans NP, Bos LDJ, et al. Respiratory viruses in invasively ventilated critically ill patients – a prospective multicenter observational study. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 29–36. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luyt CE, Combes A, Deback C, et al. Herpes simplex virus lung infection in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 935–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1322OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meyer A, Buetti N, Houhou-Fidouh N, et al. HSV-1 reactivation is associated with an increased risk of mortality and pneumonia in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2021; 25: 417. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03843-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koupaei M, Naimi A, Moafi N, et al. Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, treatment, and mortality rate of TB/COVID-19 coinfected patients: a systematic review. Front Med 2021; 8: 740593. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.740593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Masoumi M, Sakhaee F, Vaziri F, et al. Reactivation of Mycobacterium simiae after the recovery of COVID-19 infection. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2021; 24: 100257. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2021.100257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodriguez JA, Bonnano C, Khatiwada P, et al. COVID-19 coinfection with Mycobacterium abscessus in a patient with multiple myeloma. Case Rep Infect Dis 2021; 2021: 8840536. doi: 10.1155/2021/8840536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isac C, Samson HR, John A. Prevention of VAP: endless evolving evidences – systematic literature review. Nurs Forum 2021; 56: 905–915. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yousefi H, Shahabi M, Yazdannik AR, et al. The effect of daily sedation interruption protocol on early incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia among patients hospitalized in critical care units receiving mechanical ventilation. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2016; 21: 541–546. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.193420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khan R, Al-Dorzi HM, Al-Attas K, et al. The impact of implementing multifaceted interventions on the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seron-Arbeloa C, Zamora-Elson M, Labarta-Monzon L, et al. Enteral nutrition in critical care. J Clin Med Res 2013; 5: 1–11. doi: 10.5897/JCMR11.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Han J, Liu Y. Effect of ventilator circuit changes on ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care 2010; 55: 467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szarpak L, Wisco J, Boyer R. How healthcare must respond to ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in invasively mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 48: 361–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.01.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nam K, Park JB, Park WB, et al. Effect of perioperative subglottic secretion drainage on ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a retrospective, before-and-after study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021; 35: 2377–2384. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.09.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuzkat N, Demir CY. Effect of using the Suction Above Cuff Endotracheal Tube (SACETT) on postoperative respiratory complications in rhinoplasty: a randomized prospective controlled trial. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2019; 15: 571–577. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S200662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sakano T, Bittner EA, Chang MG, et al. Above and beyond: biofilm and the ongoing search for strategies to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Crit Care 2020; 24: 510. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03234-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Speck K, Rawat N, Weiner NC, et al. A systematic approach for developing a ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention bundle. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 652–656. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.World Health Organization . Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) When COVID-19 Disease is Suspected: Interim Guidance. Geneva, WHO, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331446/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2020.4-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Date last accessed: December 30, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klompas M. Eight initiatives that misleadingly lower ventilator-associated pneumonia rates. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40: 408–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kadri SS, Sun J, Lawandi A, et al. Association between caseload surge and COVID-19 survival in 558 U.S. Hospitals, March to August 2020. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 1240–1251. doi: 10.7326/M21-1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwab F, Meyer E, Geffers C, et al. Understaffing, overcrowding, inappropriate nurse:ventilated patient ratio and nosocomial infections: which parameter is the best reflection of deficits? J Hosp Infect 2012; 80: 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reyes LF, Murthy S, Garcia-Gallo E, et al. Clinical characteristics, risk factors and outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19 registered in the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: a prospective, multinational, multicentre, observational study. ERJ Open Res 2022; 8: 00552-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00552-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cantón R, Gijón D, Ruiz-Garbajosa P. Antimicrobial resistance in ICUs: an update in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Crit Care 2020; 26: 433–441. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nasa P, Azoulay E, Chakrabarti A, et al. Infection control in the intensive care unit: expert consensus statements for SARS-CoV-2 using a Delphi method. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22: e74–e87. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00626-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leone M, Bouadma L, Bouhemad B, et al. Brief summary of French guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia in ICU. Ann Intensive Care 2018; 8: 104. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0444-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chastre J, Wolff M, Fagon JY, et al. Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 2588–2598. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700582. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00582-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garduno A, Martín-Loeches I. Efficacy and appropriateness of novel antibiotics in response to antimicrobial-resistant gram-negative bacteria in patients with sepsis in the ICU. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022; 20: 513–531. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2022.1999804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luyt CE, Hékimian G, Bréchot N, et al. Aerosol therapy for pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med 2018; 39: 823–836. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kollef MH, Ricard JD, Roux D, et al. A randomized trial of the amikacin fosfomycin inhalation system for the adjunctive therapy of gram-negative ventilator-associated pneumonia: IASIS trial. Chest 2017; 151: 1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Niederman MS, Alder J, Bassetti M, et al. Inhaled amikacin adjunctive to intravenous standard-of-care antibiotics in mechanically ventilated patients with gram-negative pneumonia (INHALE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3, superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 330–340. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30574-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zampieri FG, Nassar AP Jr, Gusmao-Flores D, et al. Nebulized antibiotics for ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2015; 19: 150. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0868-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu D, Zhang J, Liu HX, et al. Intravenous combined with aerosolised polymyxin versus intravenous polymyxin alone in the treatment of pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015; 46: 603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Valachis A, Samonis G, Kofteridis DP. The role of aerosolized colistin in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 527–533. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Castanheira M, Sader HS, Deshpande LM, et al. Antimicrobial activities of tigecycline and other broad-spectrum antimicrobials tested against serine carbapenemase- and metallo-β-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae: report from the Sentry Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2008; 52: 570–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Denis JB, Lehingue S, Pauly V, et al. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and mortality in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Am J Infect Control 2019; 47: 1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chung DR, Song JH, Kim SH, et al. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant nonfermenters in hospital-acquired pneumonia in Asia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184: 1409–14017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0349OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suarez-de-la-Rica A, Serrano P, De-la-Oliva R, et al. Secondary infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: an overlooked matter? Rev Esp Quimioter 2021; 34: 330–336. doi: 10.37201/req/031.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ghanizadeh A, Najafizade M, Rashki S, et al. Genetic diversity, antimicrobial resistance pattern, and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and ventilator-associated pneumonia. BioMed Res Int 2021; 2021: 2347872. doi: 10.1155/2021/2347872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on mortality in acute respiratory infections: a patient level meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 95–107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30592-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schuetz P, Beishuizen A, Broyles M, et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided antibiotic stewardship: an international experts consensus on optimized clinical use. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019; 57: 1308–1318. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomas LC, Gidding HF, Ginn AN, et al. Development of a real-time Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA (SAM-) PCR for routine blood culture. J Microbiol Methods 2007; 68: 296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jamal W, Al Roomi E, AbdulAziz LR, et al. Evaluation of Curetis Unyvero, a multiplex PCR-based testing system, for rapid detection of bacteria and antibiotic resistance and impact of the assay on management of severe nosocomial pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 2487–2492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00325-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gadsby NJ, McHugh MP, Forbes C, et al. Comparison of Unyvero P55 Pneumonia Cartridge, in-house PCR and culture for the identification of respiratory pathogens and antibiotic resistance in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in the critical care setting. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019; 38: 1171–1178. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03526-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kunze N, Moerer O, Steinmetz N, et al. Point-of-care multiplex PCR promises short turnaround times for microbial testing in hospital-acquired pneumonia—an observational pilot study in critical ill patients. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2015; 14: 33. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0091-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Papan C, Meyer-Buehn M, Laniado G, et al. Assessment of the multiplex PCR-based assay Unyvero pneumonia application for detection of bacterial pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes in children and neonates. Infection 2018; 46: 189–196. doi: 10.1007/s15010-017-1088-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pickens CO, Gao CA, Cuttica MJ, et al. Bacterial superinfection pneumonia in patients mechanically ventilated for COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 204: 921–932. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202106-1354OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Karolyi M, Pawelka E, Hind J, et al. Detection of bacteria via multiplex PCR in respiratory samples of critically ill COVID-19 patients with suspected HAP/VAP in the ICU. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2021, in press. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao H, Su L, Ding X, et al. The risk factors for weaning failure of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study in National Medical Team Work. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 678157. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.678157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kondili E, Makris D, Georgopoulos D, et al. COVID-19 ARDS: points to be considered in mechanical ventilation and weaning. J Pers Med 2021; 11: 1109. doi: 10.3390/jpm11111109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Paparoupa M, Aldemyati R, Roggenkamp H, et al. The prevalence of early- and late-onset bacterial, viral, and fungal respiratory superinfections in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 2022; 94: 1920–1925. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sood RN, Palleiko BA, Alape-Moya D, et al. COVID-19 tracheostomy: experience in a university hospital with intermediate follow-up. J Intensive Care Med 2021; 36: 1507–1512. doi: 10.1177/08850666211043436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Long SM, Feit NZ, Chern A, et al. Percutaneous and open tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19: the Weill Cornell experience in New York City. Laryngoscope 2021; 131: E2849–E2856. doi: 10.1002/lary.29669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tetaj N, Maritti M, Stazi G, et al. Outcomes and timing of bedside percutaneous tracheostomy of COVID-19 patients over a year in the intensive care unit. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 3335. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.COVIDTrach Collaborative . COVIDTrach: a prospective cohort study of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 undergoing tracheostomy in the UK. BMJ Surg Interv Health Technol 2021; 3: e000077. doi: 10.1136/bmjsit-2020-000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Guarnieri M, Andreoni P, Gay H, et al. Tracheostomy in mechanically ventilated patients with SARS-CoV-2-ARDS: focus on tracheomalacia. Respir Care 2021; 66: 1797–1804. doi: 10.4187/respcare.09063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krowsoski L, Medina BD, DiMaggio C, et al. Percutaneous dilational tracheostomy at the epicenter of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: impact on critical care resource utilization and early outcomes. Am Surg 2021; 87: 1775–1782. doi: 10.1177/00031348211058644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ferro A, Kotecha S, Auzinger G, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of tracheostomy outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 59: 1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2021.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Prats-Uribe A, Tobed M, Villacampa JM, et al. Timing of elective tracheotomy and duration of mechanical ventilation among patients admitted to intensive care with severe COVID-19: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Head Neck 2021; 43: 3743–3756. doi: 10.1002/hed.26863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Damanti S, Cristel G, Ramirez GA, et al. Influence of reduced muscle mass and quality on ventilator weaning and complications during intensive care unit stay in COVID-19 patients. Clin Nutr 2021, in press. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Suarez-de-la-Rica A, Serrano P, De-la-Oliva R, et al. Secondary infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: an overlooked matter? Rev Esp Quimioter 2021; 34: 330–336. doi: 10.37201/req/031.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Guillon A, Hiemstra PS, Si-Tahar M. Pulmonary immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 infection: harmful or not? Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1897–1900. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06170-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Grasselli G, Cattaneo E, Florio G. Secondary infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care 2021; 25: 317. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03672-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Martin-Loeches I, Motos A, Menéndez R, et al. ICU-acquired pneumonia is associated with poor health post-COVID-19 syndrome. J Clin Med 2021; 11: 224. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]