Abstract

Objective:

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are key post-transcriptional regulators of protein translation in humans. They have an essential role in various cancers, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). The abnormal expression of miR-21 has been proven to be associated with various types of cancers, including NPC, through its targets. This study provides a systematic view of the roles of miR-21 and its network of targets (hsa-miR-21-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p) that are associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Methods:

Bioinformatics tools were applied to predict the targets of miR-21. Interactions among the targets of hsa-miR-21-3p/5p were found by the gene MANIA online tool.

Results and conclusion:

It was found that the target genes are involved in vital biological processes in cancer. In detail, a total of 95 targets of miR-21 were recorded to be associated with NPC. Therefore, they may provide new insights into nasopharyngeal pathogenesis and bring about novel targets for NPC diagnosis as well as therapy in near future.

Key Words: miRNA, miR-21, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, target gene

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor of the nasopharynx, and it has remarkably pronounced differences in distribution according to geography and inheritance, with higher incidence in Southern Asia, especially in China and Vietnam (Sham et al., 1990; Chang and Adami, 2006; Mahdavifar et al., 2016; Lao et al., 2018a; b). Recent studies have recorded the major etiological factors proposed to be associated with NPC pathogenesis, including the infection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), genetics/epigenetic changes, and environmental factor (Hildesheim and Levine, 1993; Tsao et al., 2014; Lao et al., 2017, 2018a; b; Wu et al., 2018a). Due to its deep location and ambiguous symptoms in the early stage, most NPC patients are still diagnosed in the advanced stage of NPC. However, it is potentially curable in the early stages (Yang et al., 2015; Mahdavifar et al., 2016; Lao et al., 2018a). Therefore, improved identification of potential biomarkers that promote NPC progression as well as therapeutic strategies are not only essential for the development of new diagnosis strategies but also promising treatment outcomes.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), originally discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans, typically represent ~20 nucleotides in length and are an abundant class of evolutionarily conserved, small noncoding RNAs (Lim, 2003; Feinbaum et al., 2004; Lao et al., 2018b). It has been suggested that they play key roles in the development, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of cells, and in controlling the fate of cancer cells (Bartel, 2004; Baranwal and Alahari, 2010; Iorio and Croce, 2012; Feng and Tsao, 2016; Lao et al., 2018b). Overexpression of cancer-causing miRNAs (also known as oncogenic-miRNAs or oncomirs), which promotes cancer progression, has been detected in various human cancers, including NPC, thus representing the potential application of miRNAs as biomarkers, diagnosis and therapeutic targets for human cancers (Zhang et al., 2007; Frixa et al., 2015; Lao et al., 2018a). miR-21 is a major coordinator of nasopharyngeal cancer progression by the induction of immune tolerance, which facilitates cancer cells to escape from the immune surveillance; it affects cell growth and apoptosis, leading to nasopharyngeal tumorigenesis linked with crucial biological pathways (Ou et al., 2014; Miao et al., 2015; Tanaka and Sakaguchi, 2017). Many bioinformatics tools and online databases have been developed to identify miRNA-mRNA interactions as well as to determine rapid and exact targets of miRNAs regarding their potential role in human cells to enable their functional characterization and evaluation in biological processes (Riffo-Campos et al., 2016). Therefore, this article explores the main function of miR-21 as well as its target genes by the application of bioinformatics tools to construct a systematic view of the roles of miR-21, which may provide new insights into nasopharyngeal pathogenesis and bring about novel targets for cancer therapy.

Materials and Methods

Sequence of miRNA-21

The sequence of miRNA-21, also known as hsa-mir-21, was collected from miRNA database (http://www.mirbase.org/) by application following keywords: has-miR-21 (accession number: MI0000077). The comparison among hsa-miR-21 and other miR-21 sequences was performed by BioEdit (https://bioedit.software.informer.com/).

Prediction of targets of miR-21 and hsa-miR-21-3p/5p target gene network

Different bioinformatics tools, including Microt v4 (DianaTools/index.php?r=microtv4/index), miRDB (mirdb.org), MiRNAMap (miRNAMap.mbc.nctu.edu.tw), miRMap (mirmap.ezlab.org), Mirwalk (mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de), Pictar (pictar.mdc-berdin.de), PITA (tools4mirs.org/software/target_prediction/pita/), RNA22 (cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/Interactive/), RNAhybrid (bio.tools/rnahybrid) and TargetScan (www.targetscan.org) were applied to predict the targets of miR-21. Interactions among the targets of hsa-miR-21-3p/5p were found by the gene MANIA online tool (https://genemania.org/).

Results

Sequence of miRNA-21

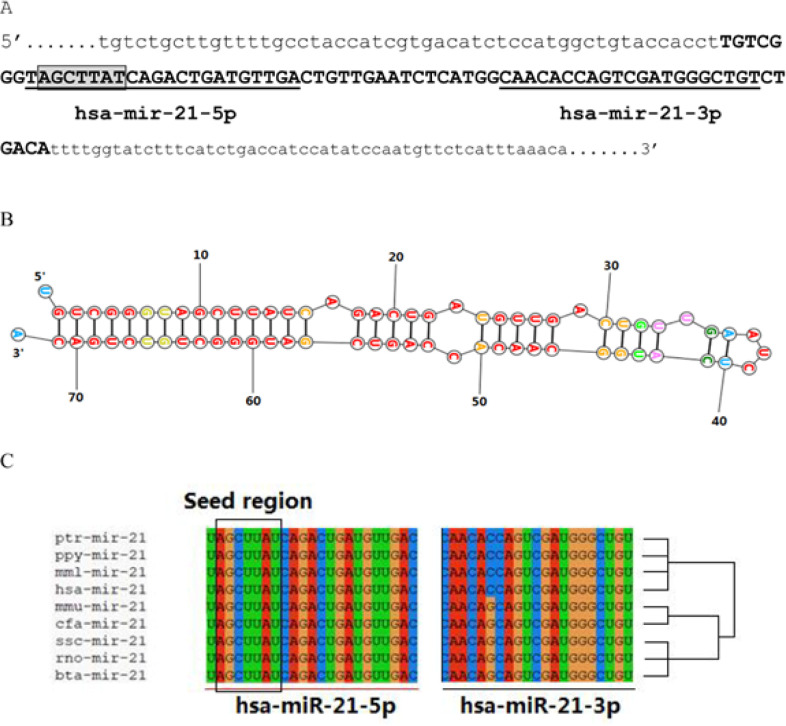

MicroRNA 21 (miR-21), also known as hsa-mir-21, is a mammalian microRNA encoded by the miR-21 gene and evolutionarily conserved across vertebrate species (LAGOS-QUINTANA, 2003; Krichevsky and Gabriely, 2008). In human genome, miR-21 is located on chromosome 17q23.2 (nt: 59,841,266 – 59,841,337 [+]) (miRBase: mirbase.org, Accession number: MI0000077). The primary transcript of miR-21 is cleaved by the Drosha ribonuclease III enzyme to produce a 72-bps-length stem-loop precursor (pre-miRNA) (ENST00000362134), which is further cleaved by the Dicer ribonuclease to produce the mature miRNA (hsa-mir-21 or hsa-mir-21-5p), consisting of the seed region, and the antisense miRNA (hsa-mir-21* or hsa-mir-21-3p) (Figure 1A, B). The final function of the miRNA strand, either expressed as the functional guide strand or degraded to the passenger strand, may be destined across evolution (Krichevsky and Gabriely, 2008; Yang et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2013). We aligned the miR-21 (hsa-miR-21) with different miR-21 sequences from various species. As shown in Figure 1C, based on the results of sequences comparison, it was indicated that hsa-miR-21 in human (Homo sapiens) has the closest evolutionary relationship with chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) and rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Furthermore, the seed region “AGCUUAU” is conserved over the mammalian evolution. Well-conserved miRNA strands in seed sequences, hsa-miR-21, may afford potential opportunities for contributing to the regulation network.

Figure 1.

Sequence of miR-21. (A) primary transcript of the miR-21. Lower letter: 5’ upstream sequence, and 3’ upstream sequence; Capital letter: sequence of 72-bps-length stem-loop precursor miR-21 (pre-miR-21); Seed of miR-12 is framed; (B) Stem-loop structure of pre-miR-21; (C) hsa-miR-21 is conserved over the mammalian evolution. Note: hsa: Homo sapiens; mmu: Mus musculus; rno: Rattus norvegicus; ssc: Sus scrofa; mml: Macaca mulatta; ptr: Pan troglodytes; ppy: Pongo pygmaeus; mmu: Mama mulatta; cfa: Canis familiaris; bta: Bos Taurus

Targets of miR-21 and their Functions in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

A total of 95 targets, 29 and 66 targets respectively for miR-21-3p and miR-21-5p, were recorded to be associated with NPC (Table 1). Among the 29 targets of miR-21-3p, 17 targets shared at least two functions related to NPC pathogenesis, including ALCAM, CSF1R, HNRNPA2B1, MDM4, PDE4D, SOX4, CLDN1, NUAK1, UBE4B, ZNF609, RSF1, MTDH, MIB1, IRX2, RASAL2, FOXO4, and RBMS3. Among the 66 targets of miR-21-5p, 21 targets shared at least two functions related to NPC pathogenesis, including PTEN, BCAT1, RAB27B, SOX2, SOX5, STAT3, TRPM7, ZNF609, PDCD4, CDK2AP1, FOXO1, SGK3, CDK6, ELF2, RASAL2, SMAD7, SOX7, TETE1, MAPK10, STYK1, and BCL2. The targets were divided into two groups, including all those predicted genes that have been confirmed to be upregulated or downregulated in different studies of NPC. Notably, differentially expressed genes were involved in cancer progression, tumor promotion, cell division of effector, migration inhibition, tumor suppression, as well as proliferation enhancement (Table 1). The targets of hsa-mir-21-3p and hsa-mir-21-5p that were associated with at least two functions of NPC progression are described in details (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Catalog of Targets of hsa-mir-21-3p/5p related NPC

| Mechanism | Targets |

|---|---|

| hsa-mir-21-3p | |

| Cancer progression | ALCAM↑, CSF1R↑, HNRNPA2B1↑, SMAD4↓, MDM4↑, PDE4D↑, SOX4↑, CLDN1↑, NUAK1, BCL2L11↑, UBE4B↑, ZNF609↑, RSF1↑, MTDH↑, MIB1↑, IRX2↑, SRSF2↑, LUC7L3↓, CTLA4↑. |

| Tumor promoter | UBE4B↑. |

| Cell division effector | RASAL2↓, SOX4↑, MTDH↑, MIB1↑. |

| Migration inhibition | RASAL2↓, NFATC2↑, ZNF609↑. |

| Tumor suppressor | CYLD↓, FOXO4↓, TSC1↑, RASAL2↓, RBMS3↓. |

| Proliferation enhancer | ALCAM↑, CSF1R↑, HNRNPA2B1↑, MDM4↑, FOXO4↓, PDE4D↑, SOX4↑, CLDN1↑, RASAL2↓, NUAK1↑, UBE4B↑, ZNF609↑, RBMS3↓, RSF1↑, MTDH↑, LIN28B↑, MIB1↑, IRX2↑. |

| Other function* | TAP1↑, TBP↑, IL20RB↑. |

| hsa-mir-21-5p | |

| Cancer progression | BCAT1↑, CDH6↑, FBXO11↑, FGD4↑, JAG1↑, LRP6↑, METTL3↑, RAB27B↑, SATB1↑, SOX2↑, SOX5↑, STAT3↑, TBL1XR1↑, TIAM1↑, TRPM7↑, ZNF609↑, PDCD4↓, BCL2↑, PTEN↓, CDK2AP1↓, FASLG↑, FOXO1↑, KLF12↑, MAP3K2↑, NETO2↑, SGK3↑, SKP2↑. |

| Tumor promoter | AGO2↑, ALDH1A1↑, CDK6↓, ELF2↑, SOX2↑, SOX5↑; STAT3↑, STYK1↑. |

| Cell division effector | RASAL2↓, TOP2A↑. |

| Migration inhibition | CHL1↓, DICER1↑, E2F3↑, RAB27B↑, SMAD7↓, SOX7↓, TET1↓, ZNF609↑, RASAL2↓, MAPK10↓, SGK3↑. |

| Tumor suppressors | KLF6↓, PDCD4↓, RASSF6↑, RECK↓, SERPINB5↓, SMAD7↓, TET1↓, TGFBR2↓, TGFBR3↓, TIMP3↓, PTEN↓, RASAL2↓, FOXO1↑, SOCS6↓. |

| Proliferation enhancer | BCAT1↑, CDK6↓, ELF2↑, HIPK3↑, SOX2↑, SOX5↑, SOX7↓, STYK1↑, TBX2↑, TLR4↑, TRPM7↑, ZNF609↑, PTEN↓, BCL2↑, RASAL2↓, CDK2AP1↓, MAPK10, SGK3↑. |

| Other function* | C7↑, CCL20↑, CTCF↑, EDNRB↑, FOXP1↑, GFPT1↑, IL1B↑, MALT1↑, MSH2↓, PHF20↑, RTN4↑, SP3↑, TAF1V, YAP1↑. |

*Note: Other functions are related to promote hypermethylation, response of immune, lytic of EBV, etc.; ↑ upregulation, ↓ downregulation.

Table 2.

Catalog of miR-21-3p Target Genes that are Functional Associated with NPC

| Gene | Associated Function |

|---|---|

| ALCAM | Role in growth of various tumors and characteristics of metastasis-associated tumor cells in vitro (Sun et al., 2019). |

| CSF1R | Upon activation of the receptor, regulating the proliferation and differentiation of cells of the mononuclear phagocytic lineage (Yang et al., 2012). |

| HNRNPA2B1 | Correlated with critical biogenesis of mRNAs by affecting pre-mRNA processing and other roles of mRNAs. HNRNPA2B1 was the downstream target of miR-146b-5p and SOX2-OT regulated NPC tumorigenesis via miR-146b-5p/HNRNPA2B1 pathway (Zhang and Li, 2019). |

| MDM4 | Regulated p53 activity, MDM4 is one of the key negative regulators of p53 and its overexpression or amplification contributes to carcinogenesis by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity (ZHANG et al., 2012). |

| FOXO4 | Plays an important role in miR-421-mediated biological functions, MDM4 is one of the key negative regulators of p53 and its overexpression or amplification contributes to carcinogenesis by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity (Chen et al., 2013). |

| PDE4D | Affecting the EGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (XU et al., 2014). |

| SOX4 | Role in controlling cell fate and differentiation, in embryonic development (Shi et al., 2015) . |

| RASAL2 | As a tumor and metastasis suppressor. RASAL2 inhibited the proliferation and metastasis capability of NPC cells (Wang et al., 2015). |

| NUAK1 | Response to cellular hypoxia and nutrient starvation (Liu et al., 2018b). |

| UBE4B | Regulates the proteasome-dependent degradation of certain substrates and involved in several biological processes. To determine the mechanism by which silencing of UBE4B inhibits tumor cell growth, the apoptosis assay was performed (Weng et al., 2019). |

| ZNF609 | Regulated Sp1 (Zhu et al., 2019). |

| RBMS3 | Role in cell proliferation; cell cycle regulation; apoptosis (Chen et al., 2012). |

| RSF1 | Transcriptional regulation, DNA replication and cell cycle progression via regulating the nucleosome remodeling. activated NF-κB pathway and promoted the expression NF-κB dependent genes involved in cell cycle and apoptosis including Survivin (Liu et al., 2017a). |

| MTDH | Role in NF-kB, PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway,repression of miR-98 leads to elevated MTDH (Tan et al., 2017). |

| MIB1 | Marker of cell proliferation (Emara et al., 2016). |

| IRX2 | Promoting oncogenesis and progression of malignant tumors (Si et al., 2018). |

| CLDN1 | Interacts with the isoenzymes of creatine kinase, tight junction proteins ZO1, ZO2, ZO3 and proteins containing the PDZ domain, to pass signals inside and outside cells and maintain the physical barrier function of tight junctions (Wu et al., 2018b). |

Table 3.

Catalog of miR-21-5p target Genes that are Functional Associated with NPC

| Gene | Function |

|---|---|

| BCAT1 | Silencing BCAT1 expression blocks NPC cell proliferation and the G1/S transition. In addition, BCAT1 knockdown cells demonstrated reduced proliferation and decreased cell migration and invasion abilities. BCAT1 overexpression may be an important early event in NPC occurrence and maintain throughout NPC progression (Zhou et al., 2013). |

| BCL2 | Bcl-2 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of NPC by regulating apoptosis (Sheu et al., 1997; Su et al., 2016). |

| CDK2AP1 | Low CDK2AP1 expression is common and associated with adverse prognosticators, conferring tumour aggressiveness through cycle cycle, cell growth or apoptosis cellular processes in NPC patients (Wu et al., 2012). |

| CDK6 | miR-143 regulates NPC cell proliferation by downregulating CDK6. CDK6 can exert its full tumor-promoting function by enhancing proliferation and stimulating angiogenesis (Kollmann et al., 2013). |

| ELF2 | ELF2 was highly expressed in NPC tissues by IHC, and over-expressed ELF2 promoted NPC cell proliferation (Chung et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017b). |

| FOXO1 | miR-3188 direct targeting of mTOR is mediated by FOXO1 suppression of p-PI3K/p-AKT/c-JUN signaling (Zhao et al., 2016). |

| MAPK10 | miR-27a-3p promoted 5–8 F growth and mobility, an effect that at least partially depended on Mapk10 (Li and Luo, 2017). |

| PDCD4 | PDCD4 also plays a role in suppressing tumor intravasation, and inhibition of PDCD4 can be achieved by regulating u-PAR gene expression (Leupold et al., 2007). In addition, TGFβ/PDCD4/AP-1 pathway is associated with NPC development and progression (Ma et al., 2017). |

| PTEN | By directly targeting PTEN, miR-144-3p enhance the proliferation and invasion of NPC cells and suppressed apoptosis, which improves PI3K-Akt signaling (Song et al., 2019). |

| RAB27B | The expression of Rab27B is associated with the radio-resistance of NPC cell lines, which is mediated by miR-20a-5p (Huang et al., 2017). |

| RASAL2 | Down-regulated expression of RASAL2 increased proliferation, migration and invasion capability via EMT induction in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells; RASAL2 inhibited the proliferation and metastasis capability of NPC cells (Wang et al., 2015). |

| SGK3 | SGK3 silencing could suppress proliferation, survival and migration of NPC cells (Chen et al., 2019). |

| SMAD7 | SMAD7 is an inhibitory role in the TGF-β signaling pathway (Luo et al., 2014); the TGF-β signaling pathway is one of the important signaling pathways in tumor cell EMT, which is an important cause of distant metastasis of malignant tumor cells (Xu et al., 2009). |

| SOX2 | SOX2 plays a vital role in the progression of multiple tumors through various mechanisms. For example, SOX2 activated lncRNA ANRIL by binding their promoters in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Wu et al., 2018b); SOX2 was also shown to regulate Lin28a to activate the AKT signaling pathway there by promoting the proliferation and maintain the self-renewal of GmGSCs-I-SB (Ma et al., 2016); SOX2 regulates nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell prolifera-tion and tumor growth through PI3K/AKT signaling (Tang et al., 2018). |

| SOX5 | SOX-5 exerts its effects on NPC progression by suppressing other oncosuppressor genes, especially SPARC (Huang et al., 2007). |

| SOX7 | MiR-494-3p could promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of NPC cells by targeting Sox7 (He et al., 2018). |

| STAT3 | EBV-induced STAT3 activation is required for and contributes directly to NPC cell proliferation and invasion (Lui et al., 2009). |

| STYK1 | STYK1 promotes Warburg effect through PI3K/AKT signaling and predicts a poor prognosis (Zhao et al., 2017). |

| TET1 | TET1 suppressed the growth of NPC cells, induced apoptosis, arrested cell division in G0/G1 phase, and inhibited cell migration and invasion. TET1 decreased the expression of nuclear β-catenin and downstream target genes. Furthermore, TET1 could cause Wnt antagonists (DACT2, SFRP2) promoter demethylation and restore its expression in NPC cells (Fan et al., 2018). |

| TRPM7 | TRPM7 is a potential regulator of cell proliferation in NPC, through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-mediated signaling pathway and other anti-apoptotic factors (Qin et al., 2016). |

| ZNF609 | ZNF609 promotes the proliferation and enhances the metastatic ability of NPC cells by absorbing microRNA-150-5p and upregulating Sp1 (Zhu et al., 2019). |

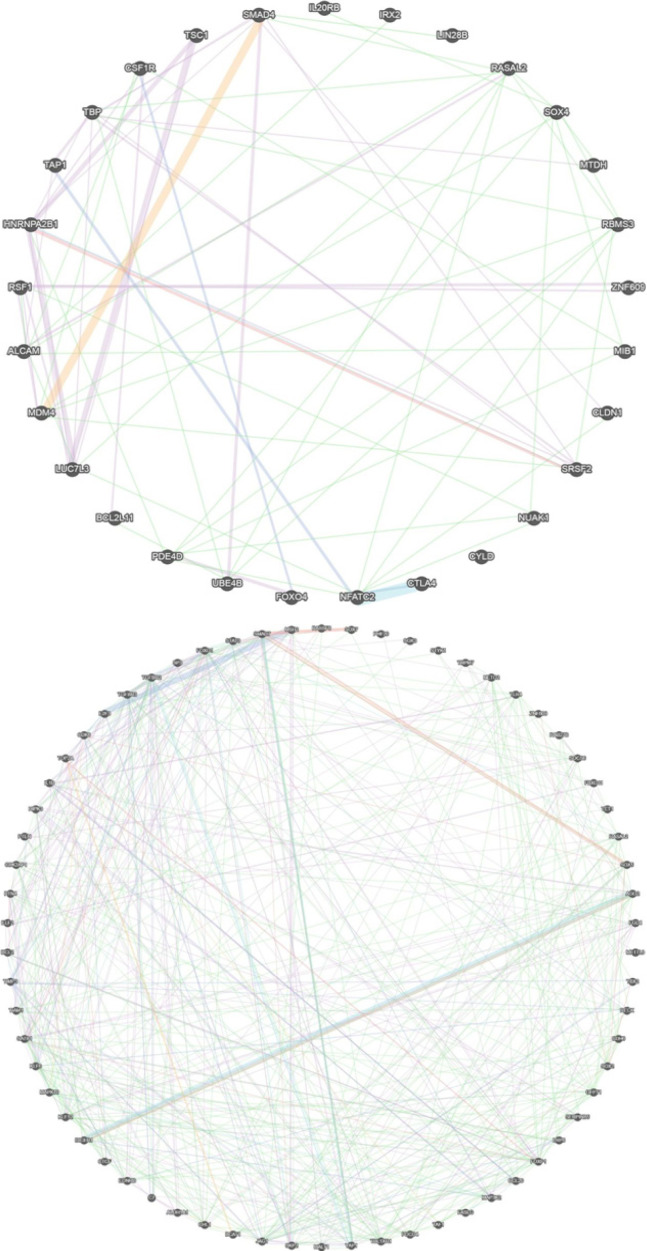

hsa-miR-21-3p/5p target gene network

Interactions among the targets of hsa-miR-21-3p/5p were found by the gene MANIA online tool (https://genemania.org/). Collectively, all targets of hsa-miR-21-3p had a co-expression of 68.54%, co-localization of 9.44%, pathway of 7.98%, prediction of 5.42%, physical interactions of 4.73%, and genetic interactions of 3.90% (Figure 2, Table 4). The hsa-miR-21-3p targets showed a similar expression (68.54%), while they tend to have a prediction of less genetic interaction. However, they were involved in the regulation of different pathways, sharing 7.89% of reactions involved in various pathways (7.77% in NCI Pathway Interaction Database and 0.21% in Reactome database). All targets of hsa-miR-21-5p had a co-expression of 53.92%, co-localization of 16.50%, pathway of 6.11%, prediction of 6.21%, physical interactions of 13.87%, and genetic interactions of 3.38% (Figure 2, Table 4). These genes are less affected by perturbation from one another.

Figure 2.

Target Genes Network Interaction between NPC Pathogenesis and (A) hsa-miR-21-3p Target Genes; (B) hsa-miR-21-5p Target Genes

Table 4.

Illustrated Interactions among the Target Genes Using Gene Mania Online Tools

| Targets of | Co-expression | Co-localization | Pathway | Predicted | Physical interactions | Genetic interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-21-3p | 68.54% | 9.44% | 7.98% | 5.42% | 4.73% | 3.90% |

| hsa-miR-21-5p | 53.92% | 16.50% | 6.11% | 6.21% | 13.87% | 3.38% |

Note: Co-expression shows that the genes are expressed together across different experimental conditions; Co-localization refers to the fact that the genes are expressed inside the same tissue or location; Pathways interaction means the protein of the genes are involved in the same reaction in a common pathway; Predicted are functions of the orthologous genes interaction obtained from a different organism; Genetic interactions means altering expression of one gene affects the expression of the other; Physical interaction means that product interact in a protein interaction study; Shared protein domain means that proteins produced by the gene are part of the same protein, enzyme or complex.

Discussion

Oncogenic miR-21 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Numerous studies have demonstrated that miR-21 is one of the most frequently over-expressed miRNAs in various types of cancer, including nasopharyngeal cancer (Ou et al., 2014; Miao et al., 2015; Tanaka and Sakaguchi, 2017), breast cancer (Iorio et al., 2005), lung cancer (Lianidou et al., 2016; Bica-Pop et al., 2018), liver cancer (Yi and Li, 2018; Liu et al., 2018a), etc. MiR-21 plays the role of an oncogenic miRNA by inhibiting phosphatase expression and limiting the activity of signaling pathways, such as AKT and MAPK, TGF-Beta, which regulate multiple cellular functions, including cell growth, differentiation, adhesion, migration and death in a context-dependent and cell type-specific manner (Buscaglia and Li, 2011; Ou et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2019). Ou et al., (2014) reported that the expression of miR-21 is abnormally high in NPC cell lines and tissues (Ou et al., 2014). Specifically, increased expression of miR-21 was observed in 29 of 42 NPC tissues compared with non-cancerous samples. Another published data indicates that miR-21 is involved in NPC cell activity. Meanwhile, Yang et al., (2016) suggested that the increasing miR-21 expression in NPC promotes the resistance of NPC cells to apoptosis caused by cisplatin (Yang et al., 2016). In addition, miR-21 was reported to inhibit the proliferation of NPC cells through a decrease in BCL2 expression. Also, Miao et al., (2015) found that miR-21 in NPC can induce the expression of IL-10 in B cells to create B-cells with immunomodulatory properties (Miao et al., 2015). These findings imply that miR-21 derived from NPC contributes to the viability of NPC cells in humans because IL-10+ B cells are one of the tolerated cells that play an important role in autoimmunity, infection and cancer (Miao et al., 2015).

Future perspectives

The results of genetic and epigenetic events, such as the perturbation of critical miRNAs and its targeting genes, affect different networks of cell cycle, apoptosis, cell adhesion, chromosome ability, etc., leading to tumorigenesis. Therefore, the evaluation of miRNA expression and its target networks could provide useful insights for the management of cancers. In this study, we focused on the roles of hsa-miR-21 (hsa-miR-21-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p) and its network of targets that are associated with NPC by prediction based on different bioinformatics tools. In this regard, a total of 95 targets of hsa-miR-21 were recorded to be associated with NPC in this study. These profiles have become a potential component of the use of hsa-miR-21 and its targets in the design of in vitro assays and evaluation of further studies with a larger cohort of NPC patients to point out the perturbation targets in comparison with healthy volunteers in cancer management as diagnostic and/or prognostic markers, including screening activities, monitoring of routine tumorigenesis, and development of miRNA therapeutics.

Regarding using miRNAs as biomarkers and target therapies, there are still a lot of challenges, including establishing the protocols for the initial and late stages of the process, the sample collection and storage, the diversity of technological methods used, and especially the biological instability of these compounds in biological fluids or tissues (Garzon et al., 2010). Other factors contributing to the challenges of candidate biomarkers in realizing clinical utility mainly include the lack of clinically relevant animal models for evaluation of their effects, the fact that one miRNA and its networks can function differently according to many biological processes as well as human diseases (Condrat et al., 2020). To overcome these obstacles, it is important to deeply consider many aspects, such as prospective studies, assessment methods, validation process, clinically relevant animal model studies, as well as the in silico screening prediction, which could provide a definitive insight into the pathways involved in human pathogenesis. Last but not the least, detailed experimental evidence is required to provide an assessment of these identified miRNAs and their target genes before they can serve as potential biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis as well as target therapies.

In conclusion, matured miR-21 (hsa-miR-21-3p and hsa-miR-21-5p) plays an important role, oncogenic-miRNA, in NPC pathogenesis. miR-21 regulated several genes that are associated with NPC in several pathways. In details, by application of bioinformatics tools, this systematic review provided new insights into the network. A total of 95 targets of miR-21 were recorded to be associated with NPC. The interactions between the target genes and hsa-mir-21-3p/5p could be helpful in better understanding of the initiation, proliferation, tumorigenesis, and metastasis of NPC.

Author Contribution Statement

All authors contributed to the design and conception of the study. Writing original draft: T.D.L.; data collection and analysis: T.D.L., M.T.Q; review and editing the manuscript: T.A.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors, thus Ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable for this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam under the grant number E2019.07.3.

Availability of data and material

The data generated during and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baranwal S, Alahari SK. miRNA control of tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1283–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bica-Pop C, Cojocneanu-Petric R, Magdo L, et al. Overview upon miR-21 in lung cancer: focus on NSCLC. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:3539–51. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2877-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscaglia LEB, Li Y. Apoptosis and the target genes of microRNA-21. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:371–80. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang ET, Adami H-O. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1765–77. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kwong DL-W, Zhu C-L, et al. RBMS3 at 3p24 inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma development via inhibiting cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and inducing apoptosis (ed Q Tao) PLoS One. 2012;7:e44636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li HL, Li BB, et al. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 3 is a potential oncogene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;85:705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tang Y, Wang J, et al. miR-421 induces cell proliferation and apoptosis resistance in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma via downregulation of FOXO4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung I-H, Liu H, Lin Y-H, et al. ChIP-on-chip analysis of thyroid hormone-regulated genes and their physiological significance. Oncotarget. 2016;7:22448–59. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condrat CE, Thompson DC, Barbu MG, et al. miRNAs as biomarkers in disease: Latest Findings Regarding Their Role in Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cells. 2020;9:276. doi: 10.3390/cells9020276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emara NM, Abd El-Maksoud AA, Ibrahim E, et al. Prognostic value of claudin-4, nm23-H1, and MIB-1 in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Egypt J Pathol. 2016;36:149–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Zhang Y, Mu J, et al. TET1 exerts its anti-tumor functions via demethylating DACT2 and SFRP2 to antagonize Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10:103. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinbaum R, Ambros V, Lee R. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 2004;116:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y-H, Tsao C-J. Emerging role of microRNA-21 in cancer. Biomed Rep. 2016;5:395–402. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frixa T, Donzelli S, Blandino G. Oncogenic MicroRNAs: Key Players in Malignant Transformation. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7:2466–85. doi: 10.3390/cancers7040904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R, Marcucci G, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–89. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Zhang Y, Zhang SJ, et al. Comprehensive analysis of key genes and microRNAs in radioresistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma. BMC Med Genomics. 2019;12:73. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Liao X, Yang Q, et al. MicroRNA-494-3p promotes cell growth, migration, and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting Sox7. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:153303381880999. doi: 10.1177/1533033818809993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildesheim A, Levine PH. Etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A Review. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:466–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Bian G, Pan Y, et al. MiR–20a-5p promotes radio-resistance by targeting Rab27B in nasopharyngeal cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:32. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D-Y, Lin Y-T, Jan P-S, et al. Transcription factor SOX-5 enhances nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression by down-regulating SPARC gene expression. J Pathol. 2007;214:445–55. doi: 10.1002/path.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio MV, Croce CM. microRNA involvement in human cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1126–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio M V., Ferracin M, Liu C-G, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7065–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmann K, Heller G, Schneckenleithner C, et al. A kinase-independent function of CDK6 links the cell cycle to tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:167–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M. New microRNAs from mouse and human. RNA. 2003;9:175–9. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao DT, Nguyen DH, Huyen Le TA. Study of mir-141 and its potential targeted mRNA PTEN expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: From in Silico to Initial Experiment Analysis. Asian J Pharm Res Heal Care. 2018a;10:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lao TD, Nguyen DH, Nguyen TM, et al. Molecular screening for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV): Detection of Genomic EBNA-1, EBNA-2, LMP-1, LMP-2 Among Vietnamese Patients with Nasopharyngeal Brush Samples. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:1675–9. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao TD, Nguyen T Van, Nguyen DH, et al. miR-141 is up-regulated in biopsies from Vietnamese patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Braz Oral Res. 2018b;32:e126. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.vol32.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leupold JH, Yang H-S, Colburn NH, et al. Tumor suppressor Pdcd4 inhibits invasion/intravasation and regulates urokinase receptor (u-PAR) gene expression via Sp-transcription factors. Oncogene. 2007;26:4550–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Luo Z. Dysregulated MIR-27a-3p promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation and migration by targeting MapklO. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:2679–87. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lianidou E, Markou A, Zavridou M. miRNA-21 as a novel therapeutic target in lung cancer. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2016;9:276. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S60341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP. The microRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2003;17:991–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.1074403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Cheng L, Cao D, et al. Suppression of miR-21 expression inhibits cell proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells by targeting phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) Med Sci Monit. 2018a;24:3571–7. doi: 10.12659/MSM.907038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li G, Liu C, et al. RSF1 regulates the proliferation and paclitaxel resistance via modulating NF-κB signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2017a;8:354–62. doi: 10.7150/jca.16720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Tang G, Huang H, et al. Expression level of NUAK1 in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2018b;275:2563–73. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tao Z, Qu J, et al. Long non-coding RNA PCAT7 regulates ELF2 signaling through inhibition of miR-134-5p in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017b;491:374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo T-F, Tsai W-C, Chen S-T. MicroRNA-21-3p, a berberine-induced miRNA, directly down-regulates human methionine adenosyltransferases 2A and 2B and inhibits hepatoma cell growth (ed MA Avila) PLoS One. 2013;8:e75628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui VWY, Wong EYL, Ho Y, et al. STAT3 activation contributes directly to Epstein-Barr virus-mediated invasiveness of nasopharyngeal cancer cells in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1884–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Li N, Lv N, et al. SMAD7: a timer of tumor progression targeting TGF-β signaling. Tumor Biol. 2014;35:8379–85. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Xuan S-H, Li Y, et al. Role of the TGFβ/PDCD4/AP-1 signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its relationship to prognosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:1392–1401. doi: 10.1159/000481871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Zhou Z, Li N, et al. Lin28a promotes self-renewal and proliferation of dairy goat spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) through regulation of mTOR and PI3K/AKT. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38805. doi: 10.1038/srep38805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavifar N, Ghoncheh M, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, et al. Epidemiology and inequality in the incidence and mortality of nasopharynx cancer in Asia. Osong Public Heal Res Perspect. 2016;7:360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao B-P, Zhang R-S, Li M, et al. Nasopharyngeal cancer-derived microRNA-21 promotes immune suppressive B cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:750–6. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou H, Li Y, Kang M. Activation of miR-21 by STAT3 induces proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting PTEN gene (ed JQ Cheng) PLoS One. 2014;9:e109929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Liao Z-W, Luo J-Y, et al. Functional characterization of TRPM7 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its knockdown effects on tumorigenesis. Tumor Biol. 2016;37:9273–83. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffo-Campos Á, Riquelme I, Brebi-Mieville P. Tools for sequence-based miRNA target prediction: What to Choose? Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1987. doi: 10.3390/ijms17121987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham JS, Choy D, Wei W, et al. Detection of subclinical riasopharyngeal carcinoma by fibreoptic endoscopy and multiple biopsy. Lancet. 1990;335:371–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90206-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu L, Chen A, Meng C, et al. Analysis of bcl-2 expression in normal, inflamed, dysplastic nasopharyngeal epithelia, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Association with p53 expression. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:556–62. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S, Cao X, Gu M, et al. Upregulated expression of SOX4 is associated with tumor growth and metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:658141. doi: 10.1155/2015/658141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J, Si Y, Zhang B, et al. Up-regulation of the IRX2 gene predicts poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:4073. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Chen L, Luan Q, et al. miR-144-3p facilitates nasopharyngeal carcinoma via crosstalk with PTEN. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:17912–24. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Lin Y, Wu F, et al. Bcl-2 regulation by miR-429 in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma in vivo. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9:5998–6006. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Lin H, Qu S, et al. Downregulation of CD166 inhibits invasion, migration, and EMT in the radio-resistant human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line CNE-2R. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3593–3602. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S194685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H, Zhu G, She L, et al. MiR-98 inhibits malignant progression via targeting MTDH in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:2554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:109–18. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Zhong G, Wu J, et al. SOX2 recruits KLF4 to regulate nasopharyngeal carcinoma proliferation via PI3K/AKT signaling. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:61. doi: 10.1038/s41389-018-0074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao SW, Yip YL, Tsang CM, et al. Etiological factors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang J, Su Y, et al. RASAL2 inhibited the proliferation and metastasis capability of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:18765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng C, Chen Y, Wu Y, et al. Silencing UBE4B induces nasopharyngeal carcinoma apoptosis through the activation of caspase3 and p53. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2553–61. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S196132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-C, Chen Y-L, Wu W-R, et al. Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2-associated protein 1 confers an independent prognosticator in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a cohort study. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:795–801. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Li C, Pan L. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A review of current updates. Exp Ther Med. 2018a;15:3687–92. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Xiao J, Zhao C, et al. Claudin1 promotes the proliferation, invasion and migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by upregulating the expression and nuclear entry of βcatenin. Exp Ther Med. 2018b;16:3445–51. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009;19:156–72. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU T, Wu S, Yuan Y, et al. Knockdown of phosphodiesterase 4D inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma proliferation via the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2110–6. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Chen J, Guo Y, et al. Identification of prognostic biomarkers for response to radiotherapy by DNA microarray in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1590–600. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-S, Phillips MD, Betel D, et al. Widespread regulatory activity of vertebrate microRNA* species. RNA. 2011;17:312–26. doi: 10.1261/rna.2537911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wu S, Zhou J, et al. Screening for nasopharyngeal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD008423. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008423.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-F, Yang G-D, Huang T-J, et al. EB-virus latent membrane protein 1 potentiates the stemness of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via preferential activation of PI3K/AKT pathway by a positive feedback loop. Oncogene. 2016;35:3419–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi PS, Li JS. High expression of miR-21 is not a predictor of poor prognosis in all patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8:733–739. doi: 10.3892/mco.2018.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YW, Guan J, Zhang Y, et al. Role of an MDM4 polymorphism in the early age of onset of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:1115–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E, Li X. LncRNA SOX2-OT regulates proliferation and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells through miR-146b-5p/HNRNPA2B1 pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:16575–88. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, et al. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Luo R, Liu Y, et al. miR-3188 regulates nasopharyngeal carcinoma proliferation and chemosensitivity through a FOXO1-modulated positive feedback loop with mTOR–p-PI3K/AKT-c-JUN. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang L, He J, et al. STYK1 promotes Warburg effect through PI3K/AKT signaling and predicts a poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2017;39:101042831771164. doi: 10.1177/1010428317711644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Feng X, Ren C, et al. Over-expression of BCAT1, a c-Myc target gene, induces cell proliferation, migration and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. CircRNA ZNF609 promotes growth and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by competing with microRNA-150-5p. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:2817–26. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201904_17558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.