Abstract

Background:

Tobacco companies and their associated businesses know that placement – where one can see and purchase their products – is critical to their success. Placement is one of the four fundamental Ps of marketing along with product, price and promotion. Placement includes identifying retail locations in important places such as in shopping districts, within neighborhoods, near schools, at beaches, and in parks. In Southeast Asia, counteracting tobacco company placement strategies that result in market penetration is essential to advancing the endgame, namely ending tobacco use. However, in Southeast Asia research on the placement of tobacco products has been limited.

Objectives:

We undertook to analyze how Philip Morris International (PMI) through its subsidiary Philip Morris Asia Inc. (PMAI), from the time the company entered Thailand’s market once it was forced open in 1990, developed its successful product placement strategies and tactics.

Methods:

We examined over 4,000 PMI and PMAI internal documents using an historical, iterative and thematic approach. We analyzed the most relevant and illuminating documents, particularly those in which PMAI discussed retailer supply, retailer acceptance and retailer cooperation.

Results:

Even before foreign tobacco brands were legally allowed to be sold in Thailand, PMAI was already doing customer research in Thailand. In 1989, PMAI conducted a study of potential Thai customers in which 24% of respondents’ lack of availability (i.e., product placement) was one of the main reasons for not smoking PMI’s products. Based on these findings, PMAI engaged in intensive internal efforts to address the placement barrier to gain share. PMAI placed considerable emphasis on “stimulating retail trade acceptance” by making payments to retailers who met agreed upon and contracted product sales targets. PMAI’s initial successes incentivizing Thai retailers by essentially buying prime retail space for placement of their brands, to crowd out local and other foreign brands, became the foundation of what evolved into a sophisticated program to make placement highly lucrative for retailers.

Conclusion:

PMAI viewed aggressive product placement as essential to success as a new entrant in Thailand, and their product placement strategies contributed substantially to capturing a large share of the market. Therefore, endgame strategies must focus on restricting product placement through surveillance of tobacco industry legal, investment and retailer actions and through stricter tobacco retailer licensing requirements and penalties.

Key Words: Placement, tobacco industry, LMIC, Endgame, Thailand

Introduction

Tobacco companies and their associated businesses have long realized that placement – where consumers can see and purchase their products – is critical to their business success (Feighery et al., 2003; Lavack and Toth, 2006; Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989b). Place is one of the four fundamental Ps of the marketing mix along with Product, Price and Promotion (Borden, 1964; Twin, 2020). The manipulation of placement by tobacco companies and the restrictions on placement enacted by governments determines where tobacco products are available, sold and consumed. Legal controls of price, product, and promotion have successfully reduced tobacco use in many countries (Chung-Hall et al., 2019). In Southeast Asia, of the four Ps, tobacco product placement has received the least attention from government agencies attempting to reduce tobacco use (Kolandai and Jirathanapiwat, 2019). The other three marketing elements have been emphasized because they have a greater influence the demand side of the commercial equation (Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2006; U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). In Southeast Asia scarcely any research has been conducted on the placement of tobacco products. In particular, placement of tobacco products in Southeast Asia has not been adequately examined from the tobacco industry’s perspective.

The place of products contributes to our experiences, thinking, impulses and actions. Features of our context influence our sense of normalcy and ordinariness, our habits in everyday life, our perceptions and beliefs, our understanding and decision-making, our specific behaviors, and our framing of social issues. Because context influences what products we use, it is essential to look at the many dimensions of context. This is particularly true when examining tobacco products (Unger et al., 2003; Zafeiridou et al., 2018).

Beginning in 1991, shortly after Thailand’s government opened their market to foreign imports, Philip Morris Thailand became the major supplier of imported cigarettes in Thailand. In 1992, Thailand passed the Tobacco Products Control Act which prohibited advertising in print, radio and television (Tobacco Control Laws, 1992a). That same year, Thailand passed the Non-smokers Health Protection Act which restricted smoking in some public places, workplaces, and public transport (Tobacco Control Laws, 1992b). Beginning in 1992 and for gradually thereafter through 2018, the government raised the excise tax rate on domestic and imported cigarettes starting at 55% of factory price for domestic and 55% of CIF Price + tariff in 1992 increasing to 63% by 2006, and eventually to 78% in 2018 (SEATCA, 2008; World Health Organization, 2019).

Philip Morris International (PMI) and its subsidiary Philip Morris Asia Inc. (PMAI) operating later locally as Philip Morris Thailand (PM Thailand) were, like all foreign tobacco companies, confronted with these restrictions and market price conditions. When PMAI entered Thailand’s market in 1991, they did so under conditions where they were highly constrained in their ability to manipulate three of the Ps. Their product – Marlboro brand cigarettes – was already developed. A premium price was already largely pre-determined because they realized that Marlboro could not compete with inexpensive domestic brands, and their products were subject to high excise taxes. Promotion was already greatly restricted because Thailand’s Tobacco Products Control Act of 1992.

Between 1991 and 2006, the smoking prevalence among males ages 15 and older decreased from 59% to 42%, and among females from 5% to 2.8% (National Statistical Office, 2019). Yet, even during this period of declining smoking rates, PM Thailand increased its market share from about 0% in 1991 to 22.5% in 2009, and further to 50% in 2019 (Euromonitor International, 2020; World Health Organization, 2012).

This study examines the role PMAI and PM Thailand’s placement strategies played in the context of what was essentially a naturalistic experiment: how, in the face of constraining conditions in the other three Ps, PMAI developed potent placement strategies to enter and penetrate Thailand’s market.

We look at tobacco product placement from a merchandising perspective, a tobacco industry perspective, and a regulatory framework perspective. To inform public policy to end the tobacco epidemic, we examine PMAI’s placement strategies through analysis of their internal documents (Bero, 2003; Slade, 1989). We also report on Thailand’s innovative responses to PMAI’s placement strategies and tactics. We discuss some potential regulatory approaches including broadening the concept of placement to include changing contextual features in modern society. Our findings identify opportunities for improving tobacco control measures focused on restricting product placement in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries to advance the tobacco endgame (McDaniel et al., 2016; Smith and Malone, 2020; Van der Eijk, 2015).

Background

Tobacco companies have long sought to make their products easily visible and readily accessible to customers. Placement within retail spaces for the purpose of making products accessible to customers is now understood as only one feature of tobacco product placement. The primary goals of tobacco merchandising are also to advertise products, stimulate purchasing, increase awareness of brands and new products, and create a sense of ordinariness by having tobacco products be sold in the same spaces as other consumer products. Tobacco product placement has two basic dimensions: 1) within a geographic area strategically selecting the locations of specific retail outlets, typically stores and shops, and 2) within a retail outlet, selecting spaces where tobacco products are displayed so that they are visible to customers, and if possible, physically accessible to customers. Placement can also include strategically locating vending machines and contracting mobile sellers such as vendors on bicycles and “cigarette girls” who offer tobacco products to potential customers.

The four Ps of marketing have some overlap, particularly between the place of products and promotion of products. If members of a sociocultural group see a specific tobacco product such as Marlboro cigarettes frequently in retail outlets, the immediate and cumulative effects of such placement can be a form of promotion, raising awareness of the product and normalizing that product’s place in society.

The supply-side placement feature of tobacco merchandizing has been carefully managed by transnational tobacco companies through their own definitions and their “gain by association” with affiliated businesses such as convenience store chains (Chapman, 2004). In some countries, tobacco companies have entered into contractual agreements with retailers to secure placement of their products in highly visible locations around sales counters (Pollay, 2007). Placement within retail spaces, particularly in “power walls” directly behind cash registers, is a longstanding tobacco industry tactic (Dewhirst, 2004). In retail settings, when products are placed prominently, consumers are exposed to pro-smoking imagery. Tobacco companies typically pay retailers for prime shelf space and provide them with branded displays (Feighery et al., 2003; Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2006).

Research on placement of tobacco products in the retail spaces has been an accelerating area of tobacco control research (Abdel Magid et al., 2020; Anesetti-Rothermel et al., 2020; Glasser and Roberts, 2021; Lawman et al., 2020; Marsh et al., 2020; Marsh et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2021; Pike et al., 2019; Pollay, 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2014; Shareck et al., 2020; Trapl et al., 2020; Valiente et al., 2020). Between 1999 and 2013, a few studies on tobacco retail placement were published in the international literature (Dewhirst, 2004; Feighery et al., 2003; Halonen et al., 2014; Lavack and Toth, 2006; Pollay, 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2014), then from 2016 increasing to more than a dozen (Abdel Magid et al., 2020; Anesetti-Rothermel et al., 2020; Glasser and Roberts, 2021; Lawman et al., 2020; Marsh et al., 2020; Marsh et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2021; Pike et al., 2019; Shareck et al., 2020; Trapl et al., 2020; Valiente et al., 2020). Most studies on tobacco retail sales have been conducted in high-income countries, although a few studies have been conducted in Southeast Asia, including in Thailand (Li et al., 2015; Phetphum and Noosorn, 2019, 2020).

Since 2018, researchers have increasingly examined the density and proximity of retail shops to neighborhoods and schools with populations vulnerable to smoking. Some of this increase has been due to the availability of geographical mapping applications that can be used to analyze where tobacco retailers are located within specific populations (Morrison et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2014; Valiente et al., 2020). A review of research findings on tobacco retailer density and proximity found that high densities of tobacco retailers are associated with factors that undermine tobacco control measures, reinforce tobacco use as a norm, and reinforce tobacco availability for youth initiation (Glasser and Roberts, 2021). One’s proximity to tobacco retailers has been found to be positively correlated with smoking, and inversely correlated with smokers’ attempts to quit smoking (Halonen et al., 2014; Tilson, 2011). Evidence also shows that tobacco retail locations are associated with tobacco-related health problems such as COPD (Kong et al., 2021). Research shows that limiting the number of tobacco retailers in a given area can result in reduced tobacco use (Tilson, 2016).

In communities where information technology is pervasive, the nature of placement has changed from a fixed location to a contextual framework of many dimensions (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2014). In terms of placement, consumers’ impressions of products now can be shaped by more than attractive retail displays. For decades, tobacco companies have relied heavily on point-of-sale displays to promote their products (Lavack and Toth, 2006). Companies are increasingly using a “wraparound approach” to create persuasive atmospherics, which provide a ubiquitous reward in the mind of the public (Ebster and Garaus, 2011). This contextual view of placement includes many attractive elements of place. It also involves placelessness, making a tobacco placement impersonal as if tobacco is just a ‘generally regarded as safe’ commodity accessible with other products as in a chain convenience store (Hefer and Nell, 2015).

Tobacco companies invest heavily in creating a sense of ubiquity of their products in society to embed them in the public’s mind, increasing the reputations of their brands, and introducing new products. In the US in 2018, tobacco companies spent $9.06 billion marketing cigarettes and smokeless tobacco (U.S. Federal Trade Commission, 2019). This amount translates to about $25 million each day, or more than $1 million every hour. Recent research has highlighted how tobacco companies use covert retail marketing placement tactics through cash incentives, experiential incentives like retailer parties, events, vacations, and targeted marketing and education to position tobacco favorably (Watts et al., 2021).

In some places, government agencies regulate tobacco product placement. Civil society groups also express their views of where tobacco products and images should not be allowed. However, in many places tobacco product placement has not been adequately defined for regulatory purposes (Lavack and Toth, 2006; Moon et al., 2018). For regulatory purposes, the environment can be broadly defined to mean “social, cultural, economic, public health and policy factors”, including neighborhoods, worksites, and virtual environments (Unger et al., 2020). Recently, the subtle effects of tobacco placements have been recognized by a research group that has developed indicators for regulatory research (Ribisl et al., 2020; Swan et al., 2020). Their regulatory outlines “the host, agent, vector and environment domain-specific collections of measures.” Contextual factors measured include youth social capital, public compliance with laws designating smoke-free spaces, point-of-sale restrictions, and restrictions on internet marketing. Four thematic areas were addressed: policy, communication, community environments, and social norms/acceptability.

Materials and Methods

To investigate PMI’s approach to placement of its products in Thailand, we examined PMI’s internal documents in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents archive at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and the Philip Morris documents archive (pmdocs.com). Searches were conducted between January and June of 2021. We used an historical, iterative and thematic approach to searching and analyzing documents. We searched seven collections of PMI and PMAI documents using keywords including “Thailand,” “placement,” “distribution,” “position,” and “retailer” in the period from 1988 to 2000 when PMAI was introducing their products in Thailand through their subsidiary PM Thailand. Our initial searches yielded over 4,000 documents, 57% mentioning product placement and distribution. We focused our search using the iterative technique of finding a relevant document and then conducting additional searches based on that document’s metadata (e.g., corporate locations, keywords, authors, topic area, and Bates and TID reference numbers). We focused on documents relevant to product placement prior to and at the opening of Thailand’s tobacco market to foreign cigarettes. We selected and report on the most relevant and illuminating documents, particularly those in which PMAI discussed retailer supply, retailer acceptance and retailer cooperation. Additionally, we examined Thailand’s regulatory responses to PMAI’s placement strategies.

Results

In the early 1980s, transnational tobacco companies recognized the potential for expansion in Southeast Asia, particularly observing that the “growth in personal incomes, shorter working weeks, and changing patterns of family labor are creating a large unsatisfied demand for leisure and recreation facilities” (Norsworthy, 1983). PMAI internal documents show that in 1980, a decade before Thailand allowed imports, PMAI had already set a goal to “work towards concluding licensee agreements in the high priority markets of Korea and Thailand (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1980). In 1986 in their five year business plan PMI reported that it had gained market share in the Philippines and Hong Kong, and had added Singapore with an emphasis on “expanding in-market visibility through innovative vehicles, such as non-branded “Marlboro Country” signage together with high impact Marlboro POSM [point-of-sale marketing], and merchandising dispensers. (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1986). In 1988, Robert P. Roper, President of PM Kabushiki Kaisha Japan who created the marketing strategy for Asia and went on to become VP of Marketing for PMI, recognized the essential role placement would have to play stating, “In the long run, the battle for market share will be won at retail, making availability and visibility of our products a top priority. Given our formidable competition, we must be more imaginative and innovative in our merchandising programs” (Roper, 1988).

Building on PMI’s early successes unlocking Japan’s market (Lambert et al., 2004; Webb 1990), the company set out to penetrate Southeast Asian markets with aggressive expansion plans (Webb, 1989). For six decades, the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM) had exclusive rights to sell cigarettes in Thailand. Phillip Morris and other US tobacco companies had successfully engaged the US Trade Representative using US Trade Act Section 301 provisions to force open markets in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989b). PMI’s internal documents show that senior PMI executives felt certain that using the same approach they could achieve the same result in Thailand. In August 1989, William Webb, President and CEO of PMI, made a presentation to PMI’s Board about prospects in Asia, and he suggested that despite Thailand’s position against accepting foreign tobacco, “…we are making some progress in our efforts to gain access to the domestic market. We anticipate resistance but expect to prevail” (Webb, 1989). In October 1990, Thailand’s government decided, under pressure from an impending anti-competition ruling from General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) member states, to open their market to foreign competition (Vateesatokit et al., 2000). Legal importation of cigarette commenced in 1991.

In the late 1980s before Thailand was forced to open its market, PMAI had made some gains in two of the four Ps in Thailand’s market. PMI’s products were available as contraband and in duty-free outlets (Gatenby, 1988; Webb, 1989). PMAI had also engaged a public relations firm to attempt some promotion efforts through “advertorials” (i.e., public relations materials distributed in media packages) (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989b; Rekart, 1989). Newspaper ads and outdoor billboard advertising PMI’s brands that had not been authorized by Thailand’s government started to appear all over the country (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989a; Vateesatokit, 2003).

PMAI’s internal documents show that even before Thailand lifted its ban, PMAI was already doing consumer research to determine what approach they should take in anticipation of Thailand opening their cigarette market. In 1989, PMAI Marketing Research Department conducted a consumer tracking study in Thailand (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989a, 1991). The research revealed that potential customers in Greater Bangkok expressed two main reasons for not smoking their products: 74% of respondents said that imported brands were expensive and 24% said they were difficult to find (i.e., lack of placement) (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1989a). Documents show that based on these findings in PMAI’s preparations to gain share, PMAI engaged in intensive internal efforts to address the main barriers of price and placement. PMAI decided to enter Thailand’s market as a premium, higher-cost brand to drive support as a superior product (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1990).

In 1990, PMAI generated a detailed internal report on Thailand that included a section “Preparation for Market Opening” (Figure 1) (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1990). PMAI recognized that

Figure 1.

Philip Morris Asia Inc. 1990 Strategic Plan for Thailand

“With marketing channels restricted or possibly nil, we will focus on merchandising to achieve consumer awareness at retail. Under consideration are clear acrylic display units specially adapted for various types of outlets. We do not expect that branding will be permitted, so the initial plan is to offer the units to retailers free of charge for specific display of Marlboro packs.”

The report went on to emphasize, “Distribution will be critical to gaining visibility and enduring availability of our products.”

In 1991, PMAI defined a primary research objective focused on increasing placement capacity: “to establish a research infrastructure in Thailand, including appointing research suppliers; and setting up an in-market-sales reporting system, a retailer information database, and a product testing system and procedure” (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1991).

This study outlined the barriers to competing with the TTM. The report emphasized the need for PMAI to boost sales by “completing organization of a distribution network which can support our brands…” (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1990). Given that in Thailand foreign and domestic tobacco companies already faced many marketing restrictions, which were further strengthened through the enactment of Thailand’s 1992 Tobacco Product Control Act which included strong restrictions on advertising (Tobacco Control Laws, 1992a), PMAI put substantial emphasis on developing market power through retail distribution as a means to strategically place their products as a way to make consumers aware of their brands while crowding out existing TTM brands. PMAI stated, “… we will focus on merchandising to achieve consumer awareness at retail.” “We intend to provide sales training, beginning prior to market opening, and have secured the services of Gene Allen for April 1991” (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1990). Gene Allen worked in PM USA’s sales training program, and he had conducted trainings in Japan (Philip Morris USA, 1985).

In August 1991, PMAI was among the first to enter Thailand’s cigarette market. Initially, PMAI did not have an office in Thailand, and instead managed its Thailand operations from its Hong Kong office. Documents show that in the critical period of market opening, PMAI concentrated on hiring and training staff, establishing an office in Bangkok. Early in 1991, PMAI had appointed a sales and distribution company to:

“put a working distribution infrastructure in place prior to our market entry. The infrastructure consisted of a fleet of vans and scooters, sales and distribution personnel (131 people), branch offices in selected key cities and a comprehensive database of retail outlets in Bangkok, allowing an effective penetration from Day 1 of entry” (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1992a).

This report on New Market Initiatives showed that investment in placement was essential. PMAI recognized and responded to substantial government imposed constraints on marketing (Figure 2) (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1992a):

Figure 2.

Philip Morris Asia Inc. 1992 Market Restrictions

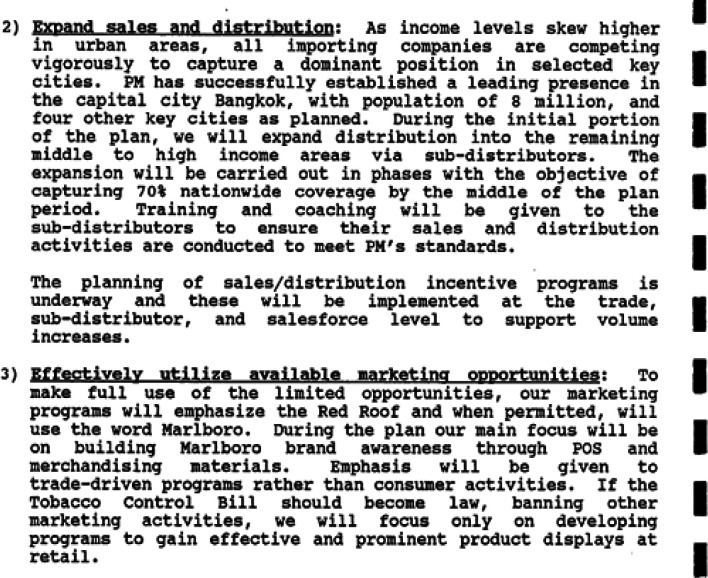

In the 1992 plan, PMAI poured resources into placement (Figure 3): “During our plan our main focus will be on building Marlboro brand awareness through POS [point-of-sale] and merchandizing materials. Emphasis will be given to trade-driven activities rather than consumer activities…we will focus only on developing programs to gain effective and prominent product displays at retail.” (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1992b).

Figure 3.

Philip Morris Asia Inc. 1992 Expanding Sales and Distribution, and Utilizing Marketing Opportunities

In the first year after entry, PM Thailand’s market share remained below 3%. However, they quickly started to outperform rival foreign companies also entering Thailand’s market, and by 1994 PM Thailand had gained 53.5% of the market share among foreign tobacco importers including RJ Reynolds, Brown & Williams, British American Tobacco, Rothmans and Japan Tobacco International (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1992b; Philip Morris Asia, 1997).

In 1994, PMI advanced their global marketing strategies with an emphasis in expanding in Asia, wherein Robert P. Roper stated to the leadership of their advertising agency Leo Burnett,

“...as part of our responsibility to protect and enhance the equity of Marlboro, we need to become better at ensuring that our promotions and point-of-sale represent more faithful extensions of our Marlboro Country heritage…Need to become better. Also that’s where the future is and if you want to grow with us is imperative…Promotions and point-of-sale will grow in importance as we lose traditional marketing vehicles” (Roper, 1994).

PMAI’s 1994 three year plan for Thailand focused heavily on expanding their distribution network in Bangkok and “upcountry” i.e., outside of Greater Bangkok (Fig. 4) (Philip Morris Thailand, 1994). Placement represented nearly their entire focus for increasing sales:

Figure 4.

PM Thailand’s 1994 Plans for Distribution Network Expansion

“Strategy: Distribution expansion – upcountry. Expand upcountry profit centers to 8 strategic locations; Increase sales force (MAU’s) to cover more outlets directly and to service sub-distributors; Continue to train sub-distributors sales reps.”

PMI discussed strategies and tactics that responded to circumstances in other countries and under different retail regulations. This indicated that PMI shared documents internationally to stimulate retailer sales practices (ERC Statistics International, 1995). Documents show how time-tested policies of establishing credibility in a new market were used in Thailand (Philip Morris Thailand, 1994). Documents show that in entering and expanding into Thailand, PMAI drew on their successes in other countries, having developed the know-how to use distributors as “target group scouts” that could “monitor trends, identify hot spots, new restaurants,” and “react swiftly to new trends and places” ( PMAI Hong Kong and Leiber, 1990). PMI described in an internal document their strategic distribution drive by providing various incentives to retailers. In marketing Marlboro, PM placed considerable emphasis on “stimulating retail trade acceptance” by making payments to retailers who met agreed upon and contracted product sales targets (Philip Morris USA, 1991). These investments in retailer rewards and sales promotions were designed to achieve consumer awareness through retail merchandising (Philip Morris Thailand, 1994; Philip Morris USA, 1994).

PMAI increasingly invested resources into placement as seen in their multi-year strategic plans (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1999; Philip Morris Thailand, 1994). They hired a corporate affairs manager in Bangkok and by 1997 boosted their sales, distribution and finance staff to 24 (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1997). Their product placement and promotion team was nearly three-quarters of the organizational staff. They spent US$ 6.1 million on market research in the Asia region and were beginning to increase sales through their contracted retailer program in Thailand. PMAI’s efforts to expand into other Southeast Asian markets built on their successes with placement in Thailand, which became a “playbook.” For example, in 1994 PMAI developed a launch plan to enter Vietnam which at the time did not allow imported cigarettes or tobacco advertising (Philip Morris Asia Inc., 1994). Two of the plan’s communication foci were to: “develop dedicated sales and distribution network” to “create awareness and impact at retail” and “branding of POSM [point-of-sale materials] at retail, thematic and branding of POSM, and fixtures inside the premises of institutional outlets.”

The product placement strategies PMAI implemented when Thailand’s market opened formed the foundation of their future success penetrating and dominating Thailand’s market. By 2015, PMI brands had 29% of the market share in Thailand (Euromonitor International, 2016). Their strategic actions, primarily in placement, brought their market share to 50% in 2019, overtaking TTM at 43%, and other transnational tobacco companies combined with the remaining 7% (Euromonitor International, 2020).

Research conducted in Thailand in 2017 showed that PM Thailand was leaning on retail shop owners to connect potential customers to their products (Phetphum et al., 2017). A report issued by the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance in 2019 documented PMAI’s tactics in Thailand and five other Southeast Asian countries of providing retailer incentives including free cigarettes, cash incentives, free merchandise, shopping vouchers, lucky draws and raffles (Kolandai and Jirathanapiwat, 2019). PMAI’s development of many of these incentives grew from their early successes in placement.

In 2005, Thailand was the first country in Asia to ban the retail display of cigarette packs at point-of-sale. Thailand recognized that displays of cigarette packs were a form of advertising, and thus required retailers to place cigarette packs behind non-transparent physical barriers so that customers could not see them. In the first post-ban survey, over 90% of smokers were aware of the ban and supported it, with three-quarters saying that the ban was effective. Subsequent surveys on consumer awareness of point-of-sale displays found that public awareness of the placement of cigarettes was the lowest shortly after the ban was implemented, but increased slightly over time, indicating that distributors and retailers had developed some tactics to circumvent the ban (Li et al., 2015). Regarding strategic location of retailers, research in 2019 and 2020 showed that in one municipality 47% of 121 tobacco retailers were located within 500 meters of schools, a form of retailer product placement, and that many retailers had violated tobacco retailing laws prohibiting self-service sales (i.e., allowing customers to pull out a pack from a slot), sales of single cigarettes, and sales to minors. Based on these findings, a youth-engaged intervention substantially reduced retailer violations (Phetphum and Noosorn, 2019, 2020).

Discussion

Our findings show that in Thailand placement was PMIA’s most important strategy for building market share with high-priced Marlboro, PMI’s most highly sought-after premium brand. PMAI built its approach to Thailand’s market using placement strategies it had developed in other countries. There was a distinct progression of steps from anticipatory actions which established PM Thailand’s dominance as the company with the largest share of imports into Thailand by 1997. First, PMAI moved to make major investments in personnel, training, distribution and retailer contracting for rapid increases in sales. Second, they consolidated their earlier work by rewarding retailers and business connections to establish a strong, sustainable position to continue its dominance in Thailand’s market. In this later period, PM Thailand used its flexibility to introduce different products and become more disruptive of constraints from health regulation and taxation.

Thailand is highly regarded for having established strong tobacco control policies in Southeast Asia (Charoenca et al., 2012). Thailand has received praise for demand-side efforts on taxation, advertising, product labeling, and smoke-free areas. The country has also engaged in some efforts to regulate and control supply-side placement (Lee and Kao, 2013). Efforts to control placement may play an increasingly important role in the future. Research in Thailand is beginning to focus on local-level concerns as provisions of the 2017 Tobacco Product Control Act, which mandates provincial tobacco control committees carry out surveillance and control measures (Tobacco Control Laws, 2017). Some surveillance and intervention measures discussed in the PhenX Toolkit for outcome assessments to inform national centers evaluating product elements like placement can be incorporated in regular local/provincial research surveillance (Ribisl et al., 2020; Swan et al., 2020; Unger et al., 2020).

Re-conceptualizing placement with consideration of how the tobacco industry has used the context to sustain tobacco use provides lessons of importance for regulatory efforts. Even high-income countries like Australia have found that there is inadequate monitoring of retail spaces, and this realization should alert tobacco regulatory bodies to the need for greater attention to the dimensions of place in tobacco control (Baker et al., 2021; Cenko and Pulvirenti, 2015; Chapman and Freeman, 2009).

Regulating product placement

While our examination of PMAI’s potent placement strategies provides a basis for regulatory actions, governments will have to contend with the fact that tobacco product placement is often blended into daily life so as to be almost invisible in plain sight, a phenomenon referred to as the ‘wallpaper effect’ (Collot, 2006). Tobacco product regulation is finding greater public acceptance. A 2015 urban survey in the U.S. showed that more than half of those questioned favored “prohibiting retailers near schools from selling tobacco, keeping tobacco products from customers’ view, and prohibiting tobacco companies from paying retailers to display or advertise tobacco products”(Farley et al., 2015).

Placement in retail space is regulated in many countries through restrictions on the number and type of retail outlets and bans on point-of-sale and in-store displays of tobacco products or representations (Center for Public Health Systems Science, 2014; Craigmile et al., 2020). One aspect of limiting tobacco product sales is specifying the areas where sales are prohibited. An example from Canada lists nineteen places where tobacco sales are not permitted by law in Canadian provinces/places (Non-Smokers’ Rights Association, 2010). As with restricting secondhand smoke exposure in public areas, it might be more appropriate to be prescriptive, to indicate where cigarettes are available for purchase, with all other commercial areas not allowed to sell cigarettes. For example, a country might restrict sales to government-controlled distribution outlets as the smoking prevalence drops and the demand becomes limited, as proposed in endgame proposals for a country or region.

Tobacco retailer licensing (TRL) is an important and effective regulatory approach to counteracting placement strategies and tactics (Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2010). TRLs can specify in which locations within a geographic area, in which spaces within an outlet, and under what conditions tobacco products may be sold. Research in regulating other products has identified principles that make licensing effective (Tilson, 2016).

TRLs are more effective when they include these features:

1. Considered a regulatory measure to protect health

2. Apply to all tobacco retailers

3. Require a separate license for each outlet

4. Require that the license displayed prominently

5. Require a payment of annual fee

6. Establish a licensing fee high enough to cover all costs associated with licensing system, including enforcement and public education.

7. Require that retailers receive no remuneration from tobacco companies

8. Enforce a graduated penalty system

9. Require that a notice of license suspension/ revocation is displayed prominently

How restricting product placement advances the tobacco endgame

Tobacco product availability, distribution and position in society influences whether tobacco prevalence will rise or fall. PMI has long understood that it must use strategic efforts to address the “global regulatory environment” (Hirschhorn, 2004). This is why tobacco control efforts have long sought to denormalize the tobacco industry by disrupting its efforts to take its place alongside other industries including through placement (Chapman, 2004).

As expected, “All anti-smoking policy measures are contended by the tobacco industry. A big issue is ‘tobacco interference’ such as tobacco donations, lobbying and pressure to stop restrictions on advertising or places where tobacco can be sold are part of the industry’s ongoing arsenal” (Rimmer, 2020). The era of the tobacco endgame – ending all use of tobacco/nicotine products – has begun (McDaniel et al., 2016; Smith and Malone, 2020; Van der Eijk, 2015). The tobacco industry fears the precedent of endgame success in any country, but now faces a movement by several countries to make tobacco use unthinkable for whole populations.

Placement in Australia’s endgame

Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence on Achieving the Tobacco Endgame (CREATE) has begun a program to support an endgame trajectory. It is a multi-stranded approach that includes retail restrictions such as licensing retailers to sell tobacco products or mandating where shops can be located. The plan’s elements are to be rolled out as the smoking prevalence drops across Australia and includes other measures, including high tobacco taxes and prohibitions of smoking in public places (Gartner and CREATE Investigator Team, 2020).

To mark the World No Tobacco Day, May 31, 2021, an open letter from 148 global public health organizations across the world called for governments to phase out commercial cigarette sales (McInerney, 2021). These organizations find that the ongoing suffering and death caused by the tobacco pandemic require similar actions taken to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments should commit to work towards phasing out sales of tobacco products. Australian organizations that signed the global letter called for stronger action in Australia (Menzies School of Health Research, 2021).

Placement in New Zealand’s endgame

In New Zealand, the government has recently proposed a plan to control tobacco use. According to Dr. Ayesha Verrall, Associate Health Minister, the proposals include reducing the access to tobacco through retail outlets as well as creating a minimum price for cigarettes and tobacco (Manch, 2021). Another possible policy includes the “smokefree generation policy” which could ban selling tobacco to those younger than 18 years of age. Other proposed measures include restricting the number of tobacco retailers by population density, licensing all tobacco and vaping retailers, setting a minimum price for tobacco, and reducing nicotine to “low levels” in tobacco products. Multiple methods are being proposed in the New Zealand Action Plan for achieving the Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 goal. ‘Tobacco-free generation’ policy (TFG) is one of the key aspects of the plan to protect future generations from tobacco harms and to phase out tobacco sales entirely (Ball et al., 2021). TFG does not allow tobacco sale to individuals born after 2003. The emphasis for enforcement is on sales of the product, not purchase or use. TFG is expected to reduce smoking prevalence in all ages in 5-10 years, in combination with other measures in the Action Plan such as taking nicotine out of tobacco, enhanced social marketing campaigns, and retail outlet reduction. When the Action Plan’s proposals to introduce retailer licensing, strengthen compliance and enforcement activity, and reduce the number of retail outlets are implemented, retail compliance with TFG will likely be enhanced.

New Zealand’s Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan has received praise as an excellent and world-leading plan (Daube and Maddox, 2021). Besides enhancing existing activities, the proposals include reducing the number of sale outlets, regulating tobacco products to make them less attractive and addictive, and gradually phasing out the legal sale of cigarettes by prohibiting sales of smoked tobacco products through the ‘smokefree generation’ policy.

In a statement accompanying the World No Tobacco Day letter, New Zealand noted that one important factor will be reducing retail availability (i.e., supply and placement in shops by increasing cost of a license or limiting the number of licenses (i.e., limiting availability geographically), banning filters (a major cause of plastic pollution), and phasing out sales through a smokefree generation strategy (McInerney, 2021). Ending smoking will require substantially restricting placement. New Zealand is pushing for this by 2025 or 2030.

Placement in California’s endgame

The California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program has established an endgame goal of ending tobacco epidemic in all population groups by 2035 throughout the state (McDaniel et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2020). Among the various endgame strategies such as prohibiting smoking in multi-unit housing, regulation of tobacco product placement is being achieved through TRLs and bans on tobacco sales in pharmacies. In response to the youth e-cigarette epidemic and youth use of flavored tobacco products and menthol cigarettes, some local jurisdictions in California (i.e., towns, cities and counties) have passed ordinances banning the sale of all flavored tobacco/nicotine products (Halstead, 2018; McClurg, 2018). In August 2020, the Governor of California signed legislation (California Legislative Information, 2020) banning the sale of most flavored tobacco products (Hiil, 2019-2020), however the implementation of the law has been suspended because of a tobacco-industry sponsored statewide ballot initiative (Thompson, 2020). The California cities of Beverly Hills and Manhattan Beach went further still, being the first in the US to pass ordinances banning the sale of all tobacco products, for which they jointly received the World Health Organization’s 2021 “World No Tobacco Day Award” in the Region of the Americas (City of Beverly Hills, 2019; City of Manhattan Beach, 2020; Lou, 2019; World Health Organization, 2021).

Conclusion

Tobacco products are the most addictive and deadly consumer products produced, and yet in most countries they are available almost everywhere at all times. This extraordinary availability makes no sense on logical or ethical grounds since research shows that consumption can be reduced by limiting availability and accessibility to tobacco products (Tilson, 2016).

It has been noted that “tobacco regulation has lagged far behind other forms of consumer protection” with smoking likely to increase in the developing world because of “the linkage in the minds of many consumers of smoking manufactured cigarettes with modernization, sophistication, wealth, and success—a connection encouraged…throughout the world.” (Brandt, 2007)

While tobacco companies’ motives for placing their products in retail spaces may appear to be for commercial reasons, the deeper reason is to make tobacco a ubiquitous and convenient part of everyday life. Removing tobacco products from public view and limiting product placement through regulatory measures is possible and should be a focus, thus changing the context of tobacco in society. If we are serious about developing endgame approaches to eliminate the threat from tobacco, we must begin to understand how tobacco companies manipulate their products’ place, visibility, distribution, and position within our context.

There is a need for further regulatory controls on tobacco product display, distribution, and positioning in the sociocultural context of countries where the tobacco industry is increasing its marketing to gain market share. PMI’s launch of “alternative products” such as e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products shows the new approaches the industry is taking to win customers’ minds and market share. The Conference of the Parties of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has developed guidelines specifying various regulatory measures needed for tobacco control. There is now an understanding that controlling the supply of tobacco will come to play a larger role in the tobacco endgame, the pathway to ending tobacco use worldwide (Smith and Malone, 2020). Countries in Southeast Asia can learn from Thailand’s experience and commit to focusing on restricting product placement through ongoing surveillance of tobacco industry legal, investment and retailer actions, and through stricter tobacco retailer licensing requirements and penalties. Ultimately, these countries can end tobacco product placement entirely by banning the sale of all tobacco products.

Author Contribution Statement

Conceptualization, N.C. and N.K.; data collection, N.C., N.K., S.H. and J.M.; methodology and analysis, S.H., J.M.; interpretation of the data, N.C., N.K., S.H. and J.M.; supervision, N.C. and N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.C., N.K., S.H. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Approval

Approved through research review of Thailand Health Promotion Institute proposed projects. Document research with no human subjects.

Ethics

Ethical review by Committee of the Thailand Health Promotion Institute.

Availability of data

Data is cited in references and is also available by request to authors.

Statement conflict of Interest

All of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have never received funding directly or indirectly from tobacco companies or their subsidiaries.

Acknowledgements

The study was partially supported for publication by the Thailand Health Promotion Institute, grant number THPI 63-0-0070. Dr. Mock’s contribution was also supported by the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program through a Mackay California-Pacific Rim Tobacco Policy Scholar Award, grant number 28MT-0082.

References

- Abdel Magid HS, Halpern-Felsher B, Ling PM, et al. Tobacco retail density and initiation of alternative tobacco product use among teens. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anesetti-Rothermel A, Herman P, Bennett M, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in the tobacco retail environment in Washington, DC: a spatial perspective. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:479–88. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Masood M, Rahman MA, Thornton L, Begg S. Identifying tobacco retailers in the absence of a licensing system: lessons from Australia. Tob Control. 2021 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055977. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J, Berrick J. Phasing out smoking: the tobacco-free generation policy. 2021. [(accessed 5.26.21)]. URL https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/phasing-out-smoking-the-tobacco-free-generation-policy.

- Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:267–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden NH. The concept of the marketing mix. J Advert Res. 1964;4:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- California Legislative Information. SB 793, Flavored tobacco products (2019-2020) 2020. URL https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB793.

- Cenko C, Pulvirenti M. Politics of evidence: The communication of evidence by ‘stakeholders’ when advocating for tobacco point-of-sale display bans in Australia. Aust J Public Adm. 2015;7:142–50. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Strategies: A Tobacco Control Guide. 2014. [(accessed 5.26.21)]. URL https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-pos-policy-WashU-2014.pdf.

- Chapman S. Advocacy in action: extreme corporate makeover interruptus: denormalising tobacco industry corporate schmoozing. Tob Control. 2004;13:445–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S, Freeman B. Regulating the tobacco retail environment: beyond reducing sales to minors. Tob Control. 2009;18:496–501. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoenca N, Mock J, Kungskulniti N, et al. Success counteracting tobacco company interference in Thailand: an example of FCTC implementation for low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:1111–34. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, Sansone N, Fong GT. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob Control. 2019;28:s119–28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Manhattan Beach. Smokefree Manhattan Beach. 2020. [accessed 5.09.21]. URL https://www.citymb.info/departments/environmental-sustainability/breathe-free-mb-smoke-free-public-areas (accessed 5.

- Collot N. The Tobacco Conspiracy. 2006. URL https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYLR_dVJ1fY (accessed 5.

- Craigmile PF, Onnen N, Schwartz E, Glasser A, Roberts ME. Evaluating how licensing-law strategies will impact disparities in tobacco retailer density: a simulation in Ohio. Tob Control. 2020 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055622. published online https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daube M, Maddox R. Impossible until implemented: New Zealand shows the way. Tob Control. 2021 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056776. published online https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst T. POP goes the power wall? Taking aim at tobacco promotional strategies utilised at retail. Tob Control. 2004;13:209–10. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebster C, Garaus M. Store design and visual merchandising: Creating store space that encourages buying. Hampton, New Jersey: Business Expert Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Passport: Cigarettes in Thailand from the Tobacco industry Interference Database. 2016. [ (accessed 4.02.21)]. URL https://sites.google.com/site/tobaccointerferencewiki/home/countries/thailand/ti-market-share-in-thailand.

- Euromonitor International. Passport: Thailand Brand Shares. 2020. URL https://www.portal.euromonitor.com/portal/statisticsevolution/index (accessed 4.

- Farley SM, Coady MH, Mandel-Ricci J, et al. Public opinions on tax and retail-based tobacco control strategies. Tob Control. 2015;24:e10–3. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Clark PI, Haladjian HH. How tobacco companies ensure prime placement of their advertising and products in stores: interviews with retailers about tobacco company incentive programmes. Tob Control. 2003;12:184–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatenby CD. Letter from CD Gatenby regarding importation of cigarettes March 15. 1988. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/grcl0207.

- Glasser AM, Roberts ME. Retailer density reduction approaches to tobacco control: A review. Health Place. 2021;67:102342. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen JI, Kivimäki M, Kouvonen A, et al. Proximity to a tobacco store and smoking cessation: a cohort study. Tob Control. 2014;23:146–51. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefer Y, Nell EC. Creating a store environment that encourages buying: a study on sight atmospherics. J Gov Regul. 2015;4:471–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn N. Corporate social responsibility and the tobacco industry: hope or hype? Tob Control. 2004;13:447–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong AY, Baggett CD, Gottfredson NC, et al. Associations of tobacco retailer availability with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related hospital outcomes, United States, 2014. Health Place. 2021;67:102464. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert A, Sargent JD, Glantz SA, Ling PM. How Philip Morris unlocked the Japanese cigarette market: lessons for global tobacco control. Tob Control. 2004;13:379–87. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavack AM, Toth G. Tobacco point-of-purchase promotion: examining tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2006;15:377–84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Borland R, Yong HH, et al. Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans in Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:9508–22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Doscher C, Cameron C, Robertson L, Petrović-van der Deen FS. How would the tobacco retail landscape change if tobacco was only sold through liquor stores, petrol stations or pharmacies? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44:34–9. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh L, Vaneckova P, Robertson L, et al. Association between density and proximity of tobacco retail outlets with smoking: a systematic review of youth studies. Health Place. 2021;67:102275. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClurg L. San Francisco passes first-in-the-nation flavored tobacco, vaping ban. KQED.org. 2018. [accessed 5.20.21]. URL https://www.kqed.org/futureofyou/441395/sf-voters-may-ban-vape-flavors-menthol-cigarettes.

- McDaniel PA, Smith EA, Malone RE. The tobacco endgame: a qualitative review and synthesis. Tob Control. 2016;25:594–604. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney M. Calls for stronger action on tobacco control in Australia to counter industry lobbying (Croakey Health Media, Issue. 2021. [(accessed 5.22.21)]. URL https://www.croakey.org/calls-for-stronger-action-on-tobacco-control-in-australia-to-counter-industry-lobbying /(accessed 5.

- Menzies School of Health Research. World No Tobacco Day: Time for governments to phase out cigarette sales. University of Queensland; 2021. URL https://nacchocommunique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Media-Statement-World-No-Tobacco-Day-Time-for-governments-to-phase-out-cigarette-sales.pdf (accessed 5. [Google Scholar]

- Moon G, Barnett R, Pearce J, Thompson L, Twigg L. The tobacco endgame: The neglected role of place and environment. Health Place. 2018;53:271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CN, Lee JP, Giovenco DP, et al. The geographic distribution of retail tobacco outlets in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dar.13285. published online https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office. hailand National Health and Welfare Survey. 2019. [ (accessed 5.22.21)]. URL http://www.nso.go.th/sites/2014en/Survey/social/SocialSecurity/health_and_welfare/2019/Full Report.pdf.

- Non-Smokers’ Rights Association. Prohibiting tobacco sales in specified outlets: policy analysis. 2010. URL http://www.nsra-adnf.ca/cms/file/files/Prohibiting_tobacco_sales_in_specified_outlets_2010.pdf (accessed 5.

- Norsworthy M. Investment Opportunities in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. 1983. [(accessed 5.22.21)]. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/txdf0201 (accessed 5.

- Phetphum C, Noosorn N. Tobacco retailers near schools and the violations of tobacco retailing laws in Thailand. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25:537–42. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phetphum C, Noosorn N. Effects of a youth-engaging intervention on illegal sales by tobacco retailers near schools in Thailand. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2020;32:340–5. doi: 10.1177/1010539520942686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phetphum C, Wangwonsin A, Noosorn N. Predicting factors for retailers’ sale of cigarettes to adolescents in the lower part of northern region of Thailand. J Res Health Sci. 2017;17:e00390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip Morris Asia Inc. PM International 1986-1990 Five Year Business Plan. 1986. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/mmxn0085 (accessed 5.

- Philip Morris Asia Inc. Report on the General Consumer Tracking Study and Omnibus Study. 1989a. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/zsvd0110 (accessed 5.

- Philip Morris Asia Inc. Thailand. 1990. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/spld0116 (accessed 5.

- Philip Morris Asia Inc. Research Overview of Singapore Malaysia Thailand. 1991. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/jjld0110 (accessed 5.

- Philip Morris Asia Inc. New Market Initiatives. 1992b. URL https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/szbd0116 (accessed 5.

- Pike JR, Shono Y, Tan N, Xie B, Stacy AW. Retail outlets prompt associative memories linked to the repeated use of nicotine and tobacco products among alternative high school students in California. Addict Behav. 2019;99:106067. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollay RW. More than meets the eye: on the importance of retail cigarette merchandising. Tob Control. 2007;16:270–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribisl KM, Chaloupka FJ, Kirchner TR, et al. PhenX: Vector measures for tobacco regulatory research. Tob Control. 2020;29:27–34. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Berke EM, Sargent J. Retail tobacco exposure: using geographic analysis to identify areas with excessively high retail density. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:155–65. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shareck M, Datta GD, Vallée J, Kestens Y, Frohlich KL. Is smoking cessation in young adults associated with tobacco retailer availability in their activity space? Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:512–21. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade J. The tobacco epidemic: lessons from history. J Psychoact Drugs. 1989;21:281–91. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1989.10472169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Malone RE. An argument for phasing out sales of cigarettes. Tob Control. 2020;29:703–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, McDaniel PA, Malone RE. California advocates’ perspectives on challenges and risks of advancing the tobacco endgame. J Public Health Policy. 2020;41:321–33. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Hendershot TP, Hamilton CM, van Bemmel DM, Wanke KL. The PhenX Toolkit: measures for tobacco regulatory research. Tob Control. 2020;29:s1–4. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco Control Laws. Thailand: Royal Thai Government. Tobacco Products Control Act. Bangkok: Royal Thai Government Gazette. 2017. [ (accessed 8.10.20)]. URL https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/thailand/laws.

- Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. The verdict is in: findings from United States v. Philip Morris, The Hazards of Smoking. 2006. [(accessed 5.20.21)]. URL https://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-verdict-is-in.pdf.

- Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; URL https://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-syn-retailer-2010.pdf (accessed 5, authors. License to Kill?: Tobacco Retailer Licensing as an Effective Enforcement Tool: A Law Synopsis. 2010.

- Unger JB, Chaloupka FJ, Vallone D, et al. PhenX: Environment measures for tobacco regulatory research. Tob Control. 2020;29:s35–42. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Cruz T, Shakib S, et al. Exploring the cultural context of tobacco use: a transdisciplinary framework. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:S101–117. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001625546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente R, Escobar F, Urtasun M, et al. Tobacco retail environment and smoking: a systematic review of geographic exposure measures and implications for future studies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:1263–73. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Eijk Y. Development of an integrated tobacco endgame strategy. Tob Control. 2015;24:336–40. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vateesatokit P, Hughes B, Ritthphakdee B. Thailand: winning battles, but the war’s far from over. Tob Control. 2000;9:122–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Burton S, Freeman B. The last line of marketing: covert tobacco marketing tactics as revealed by former tobacco industry employees. Glob Public Health. 2021;16:1000–13. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1824005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World No Tobacco Day 2021 awards - the winners. 2021. [ (accessed 5.11.21)]. URL https://www.who.int/news/item/24-05-2021-world-no-tobacco-day-2021-awards---the-winners (accessed 5.

- Zafeiridou M, Hopkinson NS, Voulvoulis N. Cigarette smoking: an assessment of tobacco’s global environmental footprint across its entire supply chain, and policy strategies to reduce it. World Health Organization. 2018. [ (accessed 5.26.21)]. URL https://www.who.int/fctc/publications/WHO-FCTC-Enviroment-Cigarette-smoking.pdf?ua=1. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is cited in references and is also available by request to authors.