Abstract

The in vitro susceptibilities of 266 isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae determined by the agar dilution method showed that 6% of isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin and 46% was resistant to erythromycin. Of the erythromycin-resistant isolates, 86.3% had the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin (MLS) resistance phenotype (constitutive MLS, 85.5%; inducible MLS, 0.8%) and 13.7% had the M phenotype.

Streptococcus agalactiae (a group B streptococcus [GBS]) is a leading cause of meningitis and bacteremia in newborns and also causes a variety of invasive diseases in pregnant women and nonpregnant adults (3, 8, 24, 30, 32). Widespread use of antibiotics, particularly penicillin, β-lactams, and erythromycin (and its newly available semisynthetic derivatives), in various clinical conditions, as well as the widely accepted efficacy of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis in decreasing early-onset neonatal GBS infections, has potentiated the emergence of antibiotic resistance (4, 17, 19, 22, 29, 31). Although isolates with lower susceptibility to penicillin have been reported, penicillin is still the recommended drug of choice for the treatment or prophylaxis of GBS infections (6, 7, 19, 23, 29). However, recent reports of the increasing incidence of macrolide and clindamycin resistance in GBS in different countries have raised concerns about the possibility of inadequate prophylaxis or treatment with these antibiotics as alternative agents in patients allergic to penicillin (1, 5, 6, 21, 29). We describe herein the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and serotype distribution of GBS isolates recovered from various clinical specimens from patients treated at the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH).

From April 1998 to October 2000, 266 isolates of S. agalactiae recovered from various clinical specimens from 266 patients treated at NTUH, a tertiary-care referral center with 2,000 beds in northern Taiwan, were studied. Of these isolates, 29 were recovered from respiratory sources (throat swab and sputum), 38 were from blood samples, 141 were from urine, 30 were from genital secretion (endocervical swab and vaginal discharge), and 28 were from other sources (wound pus, cerebrospinal fluid, and central venous catheters).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the standard agar dilution method (20). The following organisms were included as control strains: Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619. Organisms were categorized as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to the antimicrobial agents tested based on the interpretive guidelines for Streptococcus species other than S. pneumoniae provided by the NCCLS (20).

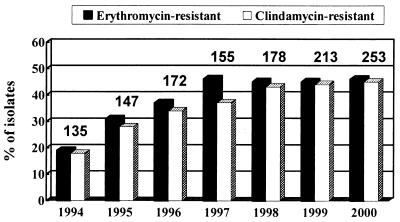

To understand the secular trend of resistance, data on the disk diffusion susceptibilities to erythromycin and clindamycin of S. agalactiae isolates recovered from 1994 to 2000 at NTUH were also analyzed.

The resistance phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant S. agalactiae were determined by the double-disk test as described previously (31). The presence of ermAM, mefE, and mefA gene sequences in chromosomal DNA of erythromycin-resistant S. agalactiae was investigated by PCR with primers as described previously (2, 25). Serotyping of each isolate was performed by the agglutination test (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). Antisera to polysaccharide antigens Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V were used.

Figure 1 shows the annual incidence of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance among the 978 isolates of S. agalactiae obtained from 1994 to 2000. A stepwise increase in erythromycin (clindamycin) resistance was found, from 19% (18%) in 1994 to 46% (37%) in 1997, and the level has remained stable over the past 4 years.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of S. agalactiae isolates resistant to clindamycin recovered at NTUH from 1994 to 1999. The values above the bars are the numbers of S. agalactiae isolates in the indicated years.

As shown in Table 1, 15 (6%) of the 266 isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin: the MIC for 11 was 0.25 μg/ml, for 3 it was 0.5 μg/ml, and for 1 it was 2 μg/ml. The last isolate was also nonsusceptible to cefotaxime and cefepime (the MIC of both drugs was 4 μg/ml). Of the 266 isolates, 48 to 55% and 43% were nonsusceptible (including intermediate and resistant isolates) to macrolides and clindamycin, respectively. Four (26.7%) of the 15 penicillin-nonsusceptible isolates were resistant to erythromycin. Fourteen percent of these isolates were nonsusceptible to quinupristin-dalfopristin. All isolates were susceptible to vancomycin, trovafloxacin, and moxifloxacin.

TABLE 1.

In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing results for 266 isolates of S. agalactiae at NTUH from April 1998 to October 2000

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

% of isolates in categorya

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | For 50% of isolates | For 90% of isolates | S | I | R | |

| Penicillin | 0.03–2 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 94 | NAb | NA |

| Cefotaxime | 0.03–4 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 99 | NA | NA |

| Cefepime | 0.03–4 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 98 | NA | NA |

| Vancomycin | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Teicoplanin | 0.03–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | NA | NA | NA |

| Gentamicin | 2–128 | 64 | 128 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.12–4 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Rifampin | 0.03–>32 | 0.12 | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Erythromycin | 0.06–>128 | 0.25 | >128 | 52 | 2 | 46 |

| Azithromycin | 0.12–>128 | 1 | >128 | 45 | 5 | 50 |

| Clindamycin | 0.06–>128 | 0.25 | >128 | 56 | 1 | 43 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 0.06–4 | 1 | 2 | 86 | NA | NA |

| Linezolid | 0.5–2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

NA, not applicable; no NCCLS breakpoint criteria (20).

Rates of resistance to erythromycin were highest in isolates from the respiratory tract (69%), followed by those from the genital tract (57%), urine (44%), and blood (34%). Sixty-one percent of 51 isolates recovered from patients aged 21 to 40 years, compared with 27% of 15 isolates from patients aged under 10 years, were resistant to erythromycin.

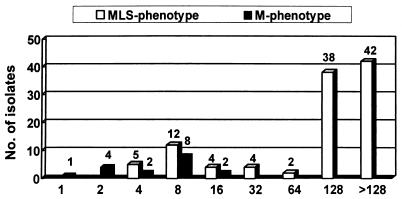

Of the 124 erythromycin-resistant (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml) isolates, 107 (86.3%) had the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin (MLS) resistance phenotype (constitutive MLS [cMLS], 85.5%; inducible MLS [iMLS], 0.8%) and 17 (13.7%) had the M phenotype (Table 2). The ermAM gene was present in 88.7% of the isolates with the cMLS phenotype, and 64.7% of the M phenotype isolates possessed both the mefE and mefA genes. The MICs for 50 and 90% of the isolates with the MLS phenotype were 128 and >128 μg/ml, and those for the isolates with the M phenotype were 8 and 16 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of erythromycin-resistant phenotypes and genotypes among 124 isolates of erythromycin-resistanta S. agalactiae

| Gene(s) | No. (%) of isolates with indicated phenotype or genotype

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cMLS | iMLS | M | Total | |

| ermAM | 94 | 1 | 0 | 95 (76.6) |

| mefE and mefA | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 (8.9) |

| Not ermAM, mefE, or mefA | 12 | 0 | 6 | 18 (14.5) |

| Total | 106 (85.5) | 1 (0.8) | 17 (13.7) | 124 (100) |

MIC, ≥1 μg/ml.

FIG. 2.

MIC distribution of erythromycin-resistant S. agalactiae according to the resistance phenotype. The values above the bars are the numbers of isolates.

Of the 266 isolates, 70% belonged to one of six serotypes, 9% belonged to two or more serotypes, and 21% were nontypeable. Serotype III prevailed in all GBS isolates, followed by lower incidences of serotypes V, Ia, Ib, II, and IV. Of the 15 isolates nonsusceptible to penicillin, six (40%) belonged to serotype V, six were nontypeable, and one each belonged to serotypes II, III, and III+IV.

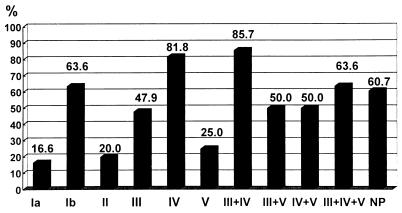

Serotype Ia, II, and V isolates were distributed more frequently in erythromycin-susceptible or -intermediate isolates (20, 13, and 21%, respectively) than in erythromycin-resistant isolates (4, 3, and 6%). Among isolates recovered from respiratory secretions, serotypes Ia, Ib, and IV predominated. For isolates recovered from blood specimens, serotype III predominated, followed by serotype Ia. Among isolates from genital secretions or urine, serotype V ranked second, next to serotype III. Figure 3 shows the rates of erythromycin resistance among isolates belonging to different serotypes. Higher percentages of erythromycin resistance were found in isolates of serotypes Ib (63.6%), IV (81.8%), and III+IV (85.7%) than in those of other serotypes. The lowest rates of erythromycin resistance occurred in isolates belonging to serotypes Ia, II, and V.

FIG. 3.

Rates of erythromycin resistance among isolates exhibiting the indicated serotype(s). The values above the bars are the rates of erythromycin resistance. NP, nontypeable.

Comparison of our results with reported resistance rates of GBS isolates from Taiwan 6 years ago and those from other countries disclosed significantly higher rates of macrolide and clindamycin resistance in recent collections of GBS in Taiwan (1, 5, 9, 18, 19, 22, 26–29, 31) (Table 3). Furthermore, the proportion of these resistant GBS isolates displaying high-level resistance (MLS phenotypes) was also higher than those reported previously(31). Interestingly, although under a similar high antibiotic selective pressure in the most recent 3 to 4 years in Taiwan, rates of macrolide resistance in GBS, as in S. pyogenes isolates, seemed to have reached a plateau (40 to 50%) (10; Hsueh et al., unpublished data). This phenomenon differs significantly from that of S. pneumoniae: its rate of macrolide resistance continued to increase (to more than 90%) (11–13; Hsueh et al., unpublished data). Extreme differences in the distribution of the M phenotype in recent isolates of S. pyogenes (>90%), S. pneumoniae (30 to 40%), and GBS (14%) in Taiwan are also impressive. The findings of our study highlight that macrolide or clindamycin is not the drug of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis or for empirical therapy of GBS diseases in Taiwan. In Taiwan, high rates of quinupristin-dalfopristin nonsusceptibility among various gram-positive bacteria have been documented (18). A similar scenario was also present in our GBS isolates.

TABLE 3.

Summary of incidences of erythromycin resistance and distribution of erythromycin resistance phenotypes

| Country | Yr(s) | No. of isolates | Source(s)a | % of erythromycin-resistant isolates

|

% of clindamycin-resistant isolates | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | MLS | M | ||||||

| Germany | 1988 | 50 | Genital (women) | 12 | 33 | 67 | 4 | 29 |

| United States | 1990 | 156 | Genital (women) | 9.0 | 9.5 | 5 | ||

| Taiwan | 1993–1994 | 128 | All | 29.7 | 68 | 32 | 24.3 | 31 |

| United States | 1992–1996 | 229 | Blood, CSF | 7.4 | 3.4 | 9 | ||

| Morocco | 1992–1997 | 59 | Blood, CSF (neonates) | 1.7 | 1 | |||

| United States | 1996–1997 | 127 | Genital (women); blood, CSF (neonate) | 21.3 | 4.0 | 22 | ||

| Korea | 1997 | 64 | Genital (women) | 5 | 13.3 | 28 | ||

| United States | 1997–1998 | 100 | Genital (women) | 18 | 28 | 72 | 5 | 19 |

| United States | 1995–1998 | 346 | Blood, CSF, throat, ear, anus, umblicus, (neonates) | 20.2 | 6.9 | 18 | ||

| Taiwan | 1998–2000 | 266 | All | 46 | 86 | 14 | 43 | PRb |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

PR, present report.

The distribution of capsular serotypes of GBS strains varies with time, source of isolation, and geographical area (1, 17, 24). In the Unites States before the 1990s, most perinatal GBS disease was due to strains of serotypes Ia, Ib, and III (1, 16). Recently, serotypes Ia, III, and V have predominated in isolates causing early-onset neonatal sepsis (17). Lachenauer et al. reported that serotypes VI and VIII prevailed among GBS isolates from pregnant Japanese women (15). In this study, the higher incidence of serotype V among isolates from genitourinary sources is impressive.

The frequency of resistant isolates is also related to particular serotypes (9, 17). Previous studies demonstrated that erythromycin resistance was notable for serotypes Ia, III, and V among isolates recovered from neonates (9, 17). Furthermore, a high percentage (up to 30 to 35%) of serotype V isolates was reported to be resistant to erythromycin among isolates from various clinical specimens (15). On the contrary, our study showed that serotypes IV, Ib, and III had higher incidences of erythromycin resistance than did serotype V. This study also demonstrated source-specific resistance patterns, with isolates from respiratory secretions having the highest erythromycin resistance.

GBS strains have been considered uniformly susceptible to penicillin (17, 18). Strains of penicillin-nonsusceptible GBS have been described, and penicillin tolerance linked to treatment failure in patients with serious GBS infection was also observed (6, 31). However, recent reports of penicillin-nonsusceptible GBS isolates are rare (1, 9, 17). The high rate (11.7%) of nonsusceptibility of GBS isolates, as well as the finding of our study (6% of GBS isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin), indicates that susceptibility surveillance of these isolates should be performed continuously (31). Interestingly, 40% of our penicillin-nonsusceptible GBS isolates belonged to serotype V. The limited number of penicillin-nonsusceptible GBS isolates tested here makes it difficult to determine the propensity of serotype V for penicillin nonsusceptibility.

In conclusion, the results presented herein from the testing of 266 recent isolates of GBS from Taiwan indicate a high incidence of macrolide resistance, particularly of the MLS phenotype, and persistence of GBS strains nonsusceptible to penicillin. Increases in resistance, together with variations in resistance patterns and in those from different sources, make local and extensive antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance crucial in establishing and/or modifying guidelines for the prophylaxis and treatment of GBS infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitmhand R, Moustaoui N, Belabbes H, Elmdaghri N, Benbachir M. Serotypes and antimicrobial susceptibility of group B streptococcus isolated from neonates in Casablanca. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:339–340. doi: 10.1080/00365540050166108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arpin C, Daube H, Tessier F, Quentin C. Presence of mefA and mefE genes in Streptococcus agalactiae. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;43:944–946. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker C J. Group B streptococcal infections. Clin Perinatol. 1997;24:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker C J, Webb B J, Barrett F F. Antimicrobial susceptibility of group B streptococci isolated from a variety of clinical sources. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;10:128–131. doi: 10.1128/aac.10.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz K, Regan J A, Greenberg E. Antibiotic resistance patterns of group B streptococci in pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:5–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.1.5-7.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betriu C, Gomez M, Sanchez A, Cruceyra A, Romero J, Picazo J. Antibiotic resistance and penicillin tolerance in clinical isolates of group B streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2183–2186. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45(RR-7):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon J M S, Lipinski A E. Infections with β-hemolytic Streptococcus resistant to lincomycin and erythromycin and observation on zonal-pattern resistance to lincomycin. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:351–356. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez M, Hickman M E, Baker C J. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of group B streptococci isolated between 1992 and 1996 from patients with bacteremia or meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1517–1519. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsueh P R, Chen H M, Huang A H, Wu J J. Decreased activity of erythromycin against Streptococcus pyogenes in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2239–2242. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsueh P R, Chen H M, Lu Y C, Huang A H, Wu J J. Antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolates in southern Taiwan. J Formosan Med Assoc. 1996;95:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Lee L N, Yang P C, Ho S W, Luh K T. Extremely high incidence of macrolide and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:897–901. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.897-901.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsueh P R, Liu Y C, Shyr J M, Wu T S, Yan J J, Wu J J, Leu H S, Chuang Y C, Lau Y J, Luh K T. Multicenter surveillance of antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis in Taiwan during the 1998–1999 respiratory season. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1342–1345. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1342-1345.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataja J, Seppala H, Skurnik M, Sarkkinen H, Huovinen P. Different erythromycin resistance mechanisms in group C and group G streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1493–1494. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachenauer C S, Kasper D L, Shimada J, Ichiman Y, Ohtsuka H, Kaku M, Paoletti L C, Ferrieri P, Madoff L C. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1030–1033. doi: 10.1086/314666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin F Y C, Clemens J, Azimi P H, Regan J A, Weisman L E, Philips III J B, Rhoads G G, Clark P, Brenner R A, Ferrieri P. Capsular polysaccharide types of group B streptococcal isolates from neonates with early-onset systemic infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:790–792. doi: 10.1086/517810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin F Y C, Azimi P H, Weisman L E, Philips III J B, Regan J A, Clark P, Rhoads G G, Clemens J, Troendle J, Pratt E, Brenner R A, Gill V. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles for group B streptococci isolated from neonates, 1995–1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:76–79. doi: 10.1086/313936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luh K T, Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Pan H J, Chen Y C, Lu J J, Wu J J, Ho S W. Quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance among gram-positive bacteria in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3374–3380. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3374-3380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales W J, Dickey S S, Bornick P, Lim D V. Change in antibiotic resistance of group B Streptococcus: impact on intrapartum management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:310–314. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: eleventh informational supplement M100–S11. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Laboratory Standards; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearlman M D, Pierson C L, Faix R G. Frequent resistance of clinical group B streptococci isolates to clindamycin and erythromycin. Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;31:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouse D J, Andrews W W, Lin E Y, Mott C W, Ware J C, Philips J B., III Antibiotic susceptibility profile of group B streptococcus acquired vertically. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrag S J, Zywicki S, Farley M M, Reingold A L, Harrison L H, Lefkowitz L B, Hadler J L, Danila R, Cieslak P R, Schuchat A. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:15–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuchat A. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal diseases in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:497–513. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tissi L, von Hunolstein C, Mosci P, Campanelli C, Bistoni F, Orefici G. In vitro efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of systemic infection and septic arthritis induced by type IV group B Streptococcus strains in mice: comparative study with erythromycin and penicillin G. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1938–1947. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsakris A, Maniatis A N. Inducible type of erythromycin resistance among group B streptococci isolated in Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:177–178. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uh Y, Jang I H, Yoon K J, Lee C H, Kwon J Y, Kim M C. Colonization rates and serotypes of group B streptococci isolated from pregnant women in a Korean tertiary hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:753–756. doi: 10.1007/BF01709259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Recklinghausen G, Fischer W, Schmidt K, Ansorg R. Resistance of Streptococcus agalactiae to erythromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:93. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C T, Hsueh P R, Sheng W H, Chang S C, Luh K T. Infected chylothorax caused by Streptococcus agalactiae: a case report. J Formosan Med Assoc. 2000;99:783–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J J, Lin K Y, Hsueh P R, Liu J W, Pan H I, Sheu S M. High incidences of erythromycin-resistant streptococci in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:844–846. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y J, Liu C C, Wang S M. Group B streptococcal infections in children: the changing spectrum of infections in infants. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1998;31:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]