Abstract

Background

Quantification of the impact of local masking policies may help guide future policy interventions to reduce SARS-COV-2 disease transmission. This study's objective was to identify factors associated with adherence to masking and social distancing guidelines.

Methods

Faculty from 16 U.S. colleges and universities trained 231 students in systematic direct observation. They assessed correct mask use and distancing in public settings in 126 US cities from September 2020 through August 2021.

Results

Of 109,999 individuals observed in 126 US cities, 48% wore masks correctly with highest adherence among females, teens and seniors and lowest among non–Hispanic whites, those in vigorous physical activity, and in larger groups (P < .0001). Having a local mask mandate increased the odds of wearing a mask by nearly 3-fold (OR = 2.99, P = .0003) compared to no recommendation. People observed in non–commercial areas were least likely to wear masks. Correct mask use was greatest in December 2020 and remained high until June 2021 (P < .0001). Masking policy requirements were not associated with distancing.

Discussion

The strong association between mask mandates and correct mask use suggests that public policy has a powerful influence on individual behavior.

Conclusions

Mask mandates should be considered in future pandemics to increase adherence.

Key Words: Mask mandates, Surveillance, Policy

Although the SARS-COV-2 virus is a serious threat to population health in all jurisdictions, the response to this pandemic has varied substantially across the United States. While vaccines offer some protection against severe morbidity and mortality, they do not eliminate transmission1; thus, in addition to vaccination, public health leaders have also recommended frequent hand-washing, wearing a mask and maintaining a distance of 6-feet from others as the best ways to effectively prevent transmission in settings where there may be close contact with others.2

Yet local decisions about disease control strategies like mask mandates and distancing guidelines have been frequently made by politicians rather than by trained public health officers. In many settings, mask mandates have been sporadic or entirely absent, and in most localities there is limited or no enforcement, regardless of whether a mask mandate exists. But other factors may also influence whether people decide to adhere to disease prevention guidelines. Two studies using direct observation found that gender and age group were strong predictors of mask adherence.3 , 4

Other issues may play a role as well, including local policy and the specific context, such as being indoors or outdoors or near family members or strangers. In addition, changes in the incidence of disease may influence the perception of threat which can affect behavior.5 , 6

As of December 16, 2021 there have been over 50 million SARS-COV-2 cases7 and more than 800,000 deaths8 in the United States since its emergence in 2020. Disease control remains a challenge despite the availability of effective vaccines. Understanding which factors may support or reduce adherence may be helpful for efforts to stem disease spread in the current pandemic and in future disease outbreaks. This national observational study assessed a variety of individual-level and contextual factors that may be associated with masking and distancing behaviors.

Methods

To obtain observations of adherence to masking and distancing guidelines across the United States, we contacted colleges and universities with departments of public health and health policy. Sixteen faculty members agreed to collaborate and work with their students to conduct observations following the Systematic Observation of Mask Adherence and Distancing (SOMAD) protocol, which has been shown to be reliable and easy to learn.3 SOMAD is based on the System of Observing Play and recreation in Communities (SOPARC) which has high reliability and validity for assessing demographic characteristics and physical activity levels.9 For SOMAD, the measurement errors between 2 observers were less than 10% among all variables for each observation. When aggregated to the day, measurement errors were less than a 1.2% difference across all variables.3

All collaborators had access to the same training and data collection materials. Observers were required to wear a mask and maintain a 6 foot distance from those observed during their fieldwork. Student data collectors were not paid for their participation, although many of the faculty provided extra credit or allowed students to obtain academic credit for their work. Others required a limited amount of participation as part of their training in field research methods but allowed students to opt out if they were concerned about any risk. Data were collected from September 2020 through August 2021.

Each observer was trained in observation and data submission. Observers picked a location to visit on a fixed schedule (eg, weekly, bi-weekly, etc.) and could choose between 2 methods of recording observations: (1) to record people passing through an area along a path or sidewalk, or (2) to record people's behavior in a specific area where they were likely to spend longer periods of time, such as a gym, park or playground. Initially, for the safety of the field staff, only outdoor locations were chosen, but as vaccines became available, indoor locations were added. There were no interactions between observers and the observed, so the Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from human subjects.

For each person observed, apparent age group (toddler, child, teen, adult, senior); gender (male, female, non–binary and/or unable to determine), race and/or ethnicity, (White, Black, Asian, Latino, unable to determine); physical activity level [sedentary, moderate (includes any movement that is not sedentary and less than vigorous), and vigorous], group size (none and/or alone, 2, 3-5, 6-9, 10+), mask adherence, and social distancing were recorded. Mask adherence was categorized as wearing a mask correctly (ie, nose and mouth fully covered), incorrectly, or no mask visible. Social distancing was defined as maintaining a 6 foot distance from others. Contextual variables included location address, location type, date and time, city, zip code and local masking policy. We divided location into 5 types and categorized as miscellaneous those that did not fit. Examples of miscellaneous areas include places like gas stations, train station, gym, and parking lots. Masking policy had 3 options: not required, recommended, or required. Google forms or Survey123 (ESRI, Redlands) were used for data entry on smart phones or tablets.

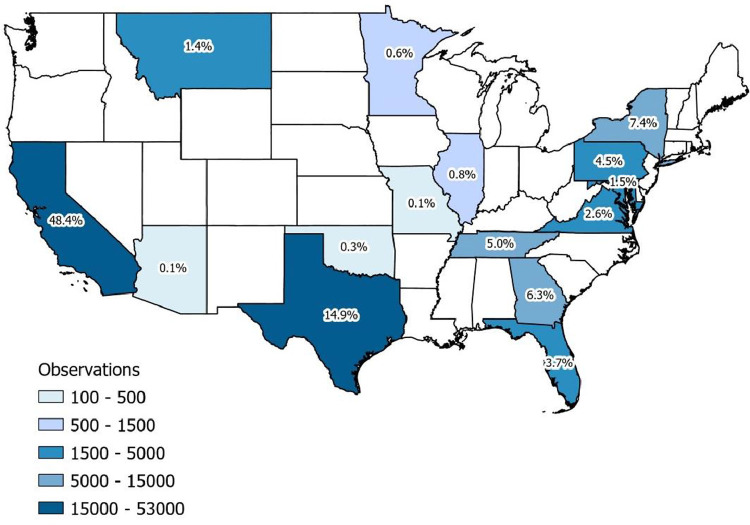

Regions were categorized as the West, Midwest, South, and Northeast. The data were highly concentrated within California (Table 1 and Fig 1 ), so the West was further divided into 4 categories: 3 California sub-regions: Southern California, North California, Central California, and the remaining states in the west into 1 group (Arizona, Montana, Nevada).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | N (%) / Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| N = 109,999 | |

| California Regions | |

| Southern California (52 Cities) | 33679 (30.6%) |

| Northern California (17 Cities) | 6687 (6.1%) |

| Central California (6 Cities) | 12843 (11.7%) |

| Arizona, Montana, Nevada | |

| Arizona (2 Cities) | 130 (0.1%) |

| Montana (1 City) | 1540 (1.4%) |

| Nevada (1 City) | 1370 (1.2%) |

| Midwest | |

| Illinois (2 Cities) | 868 (0.8%) |

| Minnesota (2 Cities) | 674 (0.6%) |

| Missouri (2 Cities) | 120 (0.1%) |

| South | |

| Florida (2 Cities) | 4109 (3.7%) |

| Georgia (14 Cities) | 6921 (6.3%) |

| Oklahoma (2 Cities) | 286 (0.3%) |

| Tennessee (6 Cities) | 5508 (5.0%) |

| Texas (3 Cities) | 16377 (14.9%) |

| Virginia (3 Cities) | 2825 (2.6%) |

| Northeast | |

| District of Columbia (1 City) | 1330 (1.2%) |

| Maryland (1 City) | 1684 (1.5%) |

| New York (8 Cities) | 8140 (7.4%) |

| Pennsylvania (1 City) | 4908 (4.5%) |

| City Population Density (1000/mi2) | 5.56 (4.48) |

| Percent of Families in Poverty | 10.41 (6.31) |

Fig 1.

Map of locations of observations of mask adherence and distancing.

Additional demographic information regarding population density, age group distribution, poverty levels of family, race and/or ethnicity distribution, and gender distribution was collected for cities, counties, and states where data were available through the 2019 Census Data and American Community Survey (ACS) 5 year estimate data.10

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the data was conducted using the Chi-Square test to identify associations between mask-adherence and local policies. Multiple logistic regression was used to determine odds ratio (OR) for correct mask use and social distancing. For both models, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to account for correlated repeated measures by geographical regions. SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS 9.4) was used to process and analyze the data. Because we had such a large data set of over 100,000 observations, we considered categories with fewer than 400 observed individuals to be insufficient for valid comparisons.

Results

A total of 231 students affiliated with 16 universities and/or colleges participated in data collection. Altogether, 109,999 individuals were observed between September 10, 2020 and August 31, 2021. Because many students were attending classes from home, data were collected from 126 different cities, with 57% of the people observed from the West, 32.8% from the South, 14.6% from the Northeast, and 1.5% from the Midwest regions of the United States (Table 1 and Fig 1). Across the cities, the mean population density was 5560/mi2and the mean percentage of families in poverty was 10.4%. The US mean population density in urbanized areas is 2500/ mi2 (US Census), indicating our observations were in higher populated areas. However, the US poverty is 11.9% at the individual level in urbanized areas,11 so our observations were in slightly wealthier neighborhoods, probably due to a larger proportion of data being collected in California.12

Masking behaviors based on local policy as well as by region, month, and location type are described in Table 2 where all comparisons within categories were significantly different at a P value < .0001. Overall, 48% of people observed wore masks correctly. There were significant differences in all the individual level factors (P < .0001), with females (52.6%), teens (59.6%) and seniors (52.9%) most likely to wear masks, and Whites (42.1%), those engaged in vigorous physical activity (20.2%), and in larger groups least likely to wear them (28.7% for groups of 6 to 9, 12.9% for groups of 10 or more).

Table 2.

Correct mask use by individuals characteristics and masking policies*

| Correct Mask Use | Correct Mask Use by Policy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Required | Recom-mended | Not Required | |

| Overall | 48.0% (52740/109999) | 66.5% (38089/57311) | 31.0% (11383/36756) | 20.5% (3268/15932) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 43.6% (23667/54300) | 61.5% (17145/27879) | 27.5% (5037/18325) | 18.3% (1485/8096) |

| Female | 52.6% (28892/54962) | 71.6% (20811/29068) | 34.8% (6306/18149) | 22.9% (1775/7745) |

| Non–Binary/Other | 24.6% (181/737) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Age | ||||

| Toddler | 9.7% (148/1525) | 15.1% (101/667) | 5.1% (32/623) | ⁎⁎ |

| Child | 30.6% (2513/8226) | 53.8% (1549/2881) | 17.9% (690/3848) | 18.3% (274/1497) |

| Teen | 59.6% (8753/14693) | 75.6% (7672/10144) | 24.9% (780/3134) | 21.3% (301/1415) |

| Adult | 47.6% (35249/74073) | 65.6% (24614/37531) | 32.9% (8383/25506) | 20.4% (2252/11036) |

| Senior | 52.9% (6077/11482) | 68.2% (4153/6088) | 41.1% (1498/3645) | 24.4% (426/1749) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non–Hispanic White | 42.1% (22315/52957) | 63.8% (16670/26112) | 24.6% (4500/18297) | 13.4% (1145/8548) |

| Non–Hispanic Black/African American | 52.0% (7729/14865) | 66.4% (4370/6579) | 43.9% (2739/6237) | 30.3% (620/2049) |

| Non–Hispanic Asian | 60.9% (6371/10459) | 79.1% (4046/5113) | 47.3% (1743/3687) | 35.1% (582/1659) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 51.4% (13573/26391) | 66.5% (10912/16416) | 26.9% (1890/7036) | 26.2% (771/2939) |

| Unknown/unable to determine | 51.7% (2752/5327) | 67.7% (2091/3091) | 34.1% (511/1499) | 20.4% (150/737) |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Sedentary | 32.9% (4332/13161) | 49.0% (2843/5805) | 23.3% (1227/5275) | 12.6% (262/2081) |

| Moderate | 53.0% (46606/87937) | 71.5% (33772/47206) | 34.8% (9930/28564) | 23.9% (2904/12167) |

| Vigorous | 20.2% (1802/8901) | 34.3% (1474/4300) | 7.8% (226/2917) | 6.1% (102/1684) |

| Group Size | ||||

| Not in a group | 52.1% (25544/49073) | 68.1% (18657/27392) | 35.2% (5298/15041) | 23.9% (1589/6640) |

| Group of 2 | 47.6% (16894/35482) | 67.2% (11824/17606) | 31.9% (3976/12463) | 20.2% (1094/5413) |

| Group of 3 to 5 | 42.6% (9563/22467) | 63.8% (7009/10982) | 24.7% (2008/8130) | 16.3% (546/3355) |

| Group of 6 to 9 | 28.7% (646/2254) | 53.0% (539/1018) | 9.1% (77/849) | ⁎⁎ |

| Group of 10 or more | 12.9% (93/723) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Distancing | ||||

| Yes | 51.9% (32293/62237) | 67.1% (23912/35633) | 35.3% (6234/17687) | 24.1% (2147/8917) |

| No | 42.8% (20447/47762) | 65.4% (14177/21678) | 27.0% (5149/19069) | 16.0% (1121/7015) |

| Location Type | ||||

| Beach/Pier/Park/Playground/Trail | 15.7% (5519/35207) | 27.7% (2694/9728) | 11.7% (2279/19560) | 9.2% (546/5919) |

| Retail | 67.9% (21249/31305) | 78.4% (15376/19618) | 61.2% (4619/7553) | 30.3% (1254/4134) |

| Street | 57.9% (10759/18579) | 66.8% (7586/11349) | 59.3% (2669/4501) | 18.5% (504/2729) |

| School/University Campus | 74.5% (8291/11124) | 81.9% (7492/9146) | 40.1% (623/1554) | 41.5% (176/424) |

| Restaurant | 50.9% (1977/3881) | 61.5% (1534/2493) | 30.1% (235/780) | 34.2% (208/608) |

| Miscellaneous Areas | 49.9% (4945/9903) | 68.5% (3407/4977) | 34.1% (958/2808) | 27.4% (580/2118) |

| Region | ||||

| Southern California | 56.5% (19017/33679) | 60.5% (16714/27622) | 41.8% (1456/3487) | 33.0% (847/2570) |

| Northern California | 44.7% (2990/6687) | 67.8% (1503/2218) | 40.5% (897/2216) | 26.2% (590/2253) |

| Central California | 31.1% (3992/12843) | 77.8% (3092/3973) | 8.8% (572/6528) | 14.0% (328/2342) |

| Arizona, Montana, Nevada | 61.6% (1872/3040) | 63.0% (1865/2961) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Midwest | 38.0% (632/1662) | 61.9% (548/885) | ⁎⁎ | 1.4% (9/658) |

| South | 47.4% (17068/36026) | 65.8% (8089/12290) | 41.3% (7900/19113) | 23.3% (1079/4623) |

| Northeast | 44.6% (7169/16062) | 85.3% (6278/7362) | 9.2% (483/5226) | 11.7% (408/3474) |

| Month-Year | ||||

| Sep-20 | 40.3% (211/524) | 44.3% (179/404) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Oct-20 | 56.0% (2238/4000) | 58.5% (2017/3450) | 40.2% (221/550) | ⁎⁎ |

| Nov-20 | 60.9% (2812/4618) | 61.3% (2738/4469) | ⁎⁎ | ⁎⁎ |

| Dec-20 | 71.5% (3148/4406) | 72.9% (2375/3260) | 67.5% (773/1146) | ⁎⁎ |

| Jan-21 | 65.7% (5584/8502) | 69.0% (4506/6531) | 54.7% (1078/1971) | ⁎⁎ |

| Feb-21 | 57.1% (7149/12525) | 67.2% (5405/8045) | 40.7% (1659/4078) | 21.1% (85/402) |

| Mar-21 | 53.7% (10107/18811) | 67.8% (8059/11881) | 31.5% (1915/6084) | 15.7% (133/846) |

| Apr-21 | 48.7% (8865/18205) | 66.0% (7670/11619) | 18.1% (1060/5874) | 19.0% (135/712) |

| May-21 | 54.6% (3081/5642) | 72.2% (2163/2997) | 35.0% (500/1430) | 34.4% (418/1215) |

| Jun-21 | 34.9% (3215/9215) | 64.0% (1730/2702) | 24.5% (896/3658) | 20.6% (589/2855) |

| Jul-21 | 21.4% (2949/13758) | ⁎⁎ | 24.2% (1607/6631) | 17.5% (1183/6762) |

| Aug-21 | 34.5% (3381/9793) | 68.5% (1088/1588) | 31.0% (1568/5065) | 23.1% (725/3140) |

| Type of Day | ||||

| Weekday (M-F) | 45.0% (29294/65163) | 63.5% (21666/34140) | 26.2% (5404/20644) | 21.4% (2224/10379) |

| Weekend (S-S) | 52.3% (23446/44836) | 70.9% (16423/23171) | 37.1% (5979/16112) | 18.8% (1044/5553) |

All P values were < .0001.

Not reported, less than 400 observations

The logistic model for mask adherence indicated similar results shown in Table 3 . Having a local policy that required masking increased the odds of wearing a mask by nearly 3-fold (OR = 2.99, P = .0003) compared to areas with no policy. Notable was the highest adherence in masking among Asians compared to Whites (OR = 2.80, P < .0001), 50% higher adherence among females compared to males (OR = 1.50, P < .0001) and the highest compliance in retail settings (OR = 1.00, reference group). People observed at beaches, piers, parks, playgrounds, or trails were least likely to wear masks (OR = 0.09, P < .0001). The odds ratio of wearing a mask was greatest in December 2020 (OR = 3.21, P value < .0001) and remained high until June 2021 (OR = 0.87, P value = .5099) compared to the first observations in September 2020. Population density and percent of families below poverty were not associated with mask adherence. We also found differences in adherence by region (highest adherence in the Northeast (OR = 1.65, P value = .0016).

Table 3.

General Estimating Equation (GEE) model predicting correct mask use and distancing

| Masking Model |

Distancing Model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||

| Toddler | 0.09 (0.06,0.14) | <.0001 | 0.33 (0.23,0.47) | <.0001 |

| Child | 0.59 (0.45,0.76) | <.0001 | 0.31 (0.24,0.40) | <.0001 |

| Teen | 0.82 (0.63,1.06) | 0.1335 | 0.50 (0.42,0.60) | <.0001 |

| Adult | 0.74 (0.65,0.83) | <.0001 | 0.80 (0.75,0.85) | <.0001 |

| Seniors | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non–Hispanic White | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Non–Hispanic Black/African American | 1.57 (1.14,2.16) | 0.0056 | 1.44 (1.25,1.65) | <.0001 |

| Non–Hispanic Asian | 2.80 (2.48,3.15) | <.0001 | 1.01 (0.90,1.13) | 0.8635 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1.51 (1.30,1.75) | <.0001 | 0.82 (0.71,0.95) | 0.0067 |

| Unknown/unable to determine | 1.74 (1.37,2.20) | <.0001 | 0.91 (0.78,1.07) | 0.2777 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Female | 1.50 (1.43,1.57) | <.0001 | 0.76 (0.70,0.81) | <.0001 |

| Non–Binary/Unknown | 0.97 (0.67,1.40) | 0.8704 | 0.86 (0.50,1.48) | 0.5795 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Sedentary | 1.35 (0.90,2.03) | 0.1420 | 0.33 (0.23,0.49) | <.0001 |

| Moderate | 2.63 (1.76,3.93) | <.0001 | 0.39 (0.26,0.59) | <.0001 |

| Vigorous | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Group* | ||||

| Not in a group | 1.81 (0.79,4.13) | 0.1609 | - | - |

| Group of 2 | 1.66 (0.67,4.09) | 0.2710 | - | - |

| Group of 3 to 5 | 1.57 (0.64,3.84) | 0.3210 | - | - |

| Group of 6 to 9 | 1.23 (0.50,3.07) | 0.6513 | - | - |

| Group of 10 or more | 1.00 (-) | - | - | - |

| Distancing* | ||||

| No | 1.00 (-) | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.18 (0.999,1.39) | 0.0522 | - | - |

| Location Type | ||||

| Retail | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Beach/Pier/Park/Playground/Trail | 0.09 (0.06,0.15) | <.0001 | 0.79 (0.65,0.96) | 0.0163 |

| Restaurant | 0.39 (0.29,0.53) | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.42,1.82) | 0.7258 |

| Miscellaneous Areas | 0.41 (0.25,0.68) | 0.0004 | 1.52 (0.53,4.36) | 0.4324 |

| Street | 0.42 (0.26,0.66) | 0.0002 | 0.83 (0.55,1.25) | 0.3779 |

| School/University Campus | 0.68 (0.33,1.40) | 0.2924 | 1.67 (0.88,3.17) | 0.1137 |

| Month-Year | ||||

| Sep-20 | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Oct-20 | 1.57 (1.26,1.95) | <.0001 | 1.15 (0.96,1.39) | 0.1338 |

| Nov-20 | 1.69 (1.44,1.99) | <.0001 | 1.15 (0.88,1.49) | 0.3167 |

| Dec-20 | 3.21 (2.11,4.87) | <.0001 | 1.17 (0.96,1.43) | 0.1271 |

| Jan-21 | 2.72 (2.25,3.29) | <.0001 | 1.12 (1.05,1.19) | 0.0005 |

| Feb-21 | 2.92 (2.29,3.72) | <.0001 | 1.39 (1.11,1.74) | 0.0039 |

| Mar-21 | 2.68 (2.02,3.55) | <.0001 | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | 0.4850 |

| Apr-21 | 2.41 (1.78,3.25) | <.0001 | 0.87 (0.77,0.97) | 0.0139 |

| May-21 | 2.21 (1.14,4.27) | 0.0186 | 0.74 (0.62,0.88) | 0.0005 |

| Jun-21 | 0.87 (0.56,1.33) | 0.5099 | 1.02 (0.74,1.42) | 0.8837 |

| Jul-21 | 0.52 (0.33,0.83) | 0.0066 | 1.16 (0.85,1.58) | 0.3539 |

| Aug-21 | 0.89 (0.63,1.26) | 0.5203 | 1.07 (0.84,1.37) | 0.5891 |

| Population Density (1000/sq. mile) | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 0.5351 | 1.02 (0.98,1.07) | 0.2971 |

| Percent Families below poverty line | 1.01 (0.98,1.04) | 0.6785 | 0.98 (0.96,0.9998) | 0.0479 |

| Region | ||||

| Southern California | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Northern California | 1.62 (0.98,2.68) | 0.0611 | 1.71 (1.13,2.59) | 0.0109 |

| Central California | 0.55 (0.42,0.73) | <.0001 | 0.82 (0.63,1.06) | 0.1354 |

| Arizona, Montana, Nevada | 0.89 (0.71,1.13) | 0.3449 | 0.59 (0.32,1.10) | 0.0981 |

| Midwest | 0.90 (0.55,1.49) | 0.6899 | 0.66 (0.50,0.89) | 0.0054 |

| South | 1.14 (0.88,1.47) | 0.3336 | 0.91 (0.73,1.12) | 0.3755 |

| Northeast | 1.65 (1.21,2.25) | 0.0016 | 0.53 (0.36,0.76) | 0.0007 |

| Local Masking Policy | ||||

| Not Required | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Recommended | 1.60 (0.82,3.12) | 0.1693 | 0.78 (0.53,1.15) | 0.2102 |

| Required | 2.99 (1.66,5.39) | 0.0003 | 1.14 (0.72,1.80) | 0.5701 |

| Type of Day | ||||

| Weekend (S-S) | 1.00 (-) | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Weekday (M-F) | 0.93 (0.83,1.04) | 0.1864 | 1.52 (1.26,1.83) | <.0001 |

| Correct Mask Usage⁎⁎ | ||||

| No | - | - | 1.00 (-) | - |

| Yes | - | - | 1.22 (1.06,1.40) | 0.0051 |

Not used for Distancing Model,

Not used in Mask Adherence model.

The model for distancing is also shown in Table 3. Masking policy requirements were not associated with an increase in observed distancing. Compared to seniors, all other age groups were less likely to distance (toddler OR = 0.33; child OR = 0.31; teen OR = 0.50; adult OR = 0.80; all P < .0001). Compared to non–Hispanic Whites, Black and/or African Americans were more likely to distance (OR = 1.44, P < .0001), and Latinos were less likely to distance (OR = 0.82, P = .0067).

People were less likely to distance if they were female (OR = 0.76, P < .0001), or engaging in sedentary (OR = 0.33, P < .0001) or moderate physical activity (OR = 0.39, P < .0001).

Compared to September, in January and February 2021 there was increased distancing (OR = 1.12, P = .0005; OR = 1.39, P = .0039), but this was reduced in April and May 2021 (OR = 0.87, P = .0139; OR = 0.74, P = .0005). Population density was not associated with distancing, but the odds of distancing was reduced by 2% for each percent increase in poverty (OR = 0.98, P = .0479).

Discussion

This study suggests that masking mandates play a significant role in influencing people to wear masks. With the exception of the month of December 2020, having a masking mandate was the strongest factor associated with mask adherence, with a 3-fold difference in adherence between settings with a mask mandate compared to those without, even though most jurisdictions did not have strong mechanisms of enforcement at the individual level.

In many other areas of public health, policies do matter even when there is limited enforcement, but acceptance may take decades. For example, requirements for seat belt use were initially resisted when introduced in the 1980s because seatbelts were uncomfortable and restrictive and some considered them a violation of individual freedom. Yet over several decades adherence has climbed from 14% to over 90%, except in New Hampshire where seatbelt use is not mandated and compliance is closer to 70%.13

Regardless of local SARS-COV-2 control policies, within each jurisdiction there were large differences in mask wearing and distancing by gender, age group, race and/or ethnicity and setting types. Disparities were also seen in studies where participants self-reported their mask wearing behaviors.14 , 15 These differences should be considered when developing future campaigns to increase adherence to public health guidelines. Specific messages targeting groups who are less likely to be compliant (eg, males, children) should be highlighted in media campaigns. Given the appearance of new, more infectious variants,16 that vaccinated individuals can also transmit the virus,1 and not all individuals are eligible for vaccination, handwashing, masking and distancing will continue to remain critical to SARS-COV-2 disease control strategies.

This study had several limitations. The data were collected from locations where field staff were willing to visit and observe safely. Consequently, the observational data may not constitute a representative sample. Additionally, both distancing and mask adherence may be transient, and our sampling represents a snapshot in time and may not reflect the overall prevalence of behaviors. Although reliability of masking adherence between observers is high,3 observations of apparent gender, age group and race and/or ethnicity may not always be fully valid considering that many were wearing masks. Because we started the study with only outdoor observations, there is also a partial confounding in the study design by time, location setting and geographic location which cannot fully be disentangled even though we controlled for time, setting and location.

This study also demonstrates that it is possible to develop a rapid response network and cooperation from academicians and students concerned about population health. Participation went beyond the concept of “citizen scientists” given that many students shared their findings in real time with local public health departments.

Within each locality it was possible to see differences associated with individual level factors, but only by aggregating the data collected across the nation was it possible to appreciate the power of policies to support self-protective behaviors. Given the continued threat of SARS-COV-2, these findings should be considered when developing or adopting policies to stem disease transmission.

Direct observation has previously been used for observing a wide variety of behaviors, including physical activity, educational interactions, and social interactions. It is a strong scientific method with more credibility than self-report. This study demonstrates it can be adopted widely.

Conclusion

Given a 3-fold increase in adherence in the presence of a mask mandates and evidence that masking protects users and others from infection, public health leaders should consider implementing such mandates in future respiratory viral pandemics.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by Resolve to Save Lives and NHLBI, R01HL145145. Neither institution had any role in the study design or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.CDC. Delta Variant: What We Know About the Science. 2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html

- 2.CDC. How to Protect Yourself & Others. 2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

- 3.Cohen DA, Talarowski M, Awomolo O, Han B, Williamson S, McKenzie TL. Systematic observation of mask adherence and distancing (SOMAD): findings from Philadelphia. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haischer MH, Beilfuss R, Hart MR, et al. Who is wearing a mask? Gender-, age-, and location-related differences during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark C, Davila A, Regis M, Kraus S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: an international investigation. Glob Transit. 2020;2:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes O, Portugal LC, Alves RC, et al. How you perceive threat determines your behavior. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:632. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. COVID Data Tracker. Available at: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home. Published 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021.

- 8.NYTimes. Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count. NYTimes2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html

- 9.Han B, Cohen DA, Derose KP, Marsh T, Williamson S, Raaen L. Validation of a new counter for direct observation of physical activity in parks. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:140–144. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.USCensus. American Community Survey. American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimate data. 2019. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.2019

- 11.USCensus. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. 2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

- 12.USDA-ERS. Data show U.S. poverty rates in 2019 higher in rural areas than in urban for racial/ethnic groups. 2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=101903

- 13.Roos D. When new seat belt laws drew fire as a violation of personal freedom. 2020. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/seat-belt-laws-resistance

- 14.Hearne BN, Nino MD. Understanding how race, ethnicity, and gender shape mask-wearing adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the COVID impact survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:176–183. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00941-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daoust JF. Elderly people and responses to COVID-19 in 27 Countries. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. What You Need to Know About Variants. 2021. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/about-variants.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fvariants%2Fvariant.html