Abstract

The effects of cathelicidins against oral bacteria and clinically important oral yeasts are not known. We tested the susceptibilities of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Streptococcus sanguis, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis and Candida albicans to the following cathelicidins: FALL39, SMAP29, and CAP18. SMAP29 and CAP18 were antimicrobial, whereas FALL39 did not exhibit antimicrobial activity. Future studies are needed to determine the potential use of these antimicrobial peptides in prevention and treatment of oral infections.

Innate immunity plays a significant role in the response to microbial colonization seen in periodontal diseases and yeast infections (25). As a part of the innate response, secretory immunoglobulin A and several factors, such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, peroxidases, antimicrobial peptides, histatins, defensins, and cathelicidins, neutralize microbial components (11, 20).

Cathelicidins are a novel family of antimicrobial peptides found in the secondary granules of neutrophils and expressed early in myeloid differentiation (6, 15, 24). The expression of the human cathelicidin FALL39 (also called hCAP18 or LL37) has been shown in keratinocytes (4) and in nonkeratinized squamous epithelia of the mouth and tongue in humans (18). Preliminary evidence from our laboratories demonstrates that cathelicidins are present in saliva and expressed in gingival tissues (unpublished data). LL37 has been shown to have antimicrobial activity against a broad range of bacteria (23).

Recently, other mammalian cathelicidins have shown effective killing against a number of human pathogens. CAP18, a cathelicidin from rabbit neutrophils, binds and neutralizes endotoxin and has broad-spectrum activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (3, 12). SMAP29, a sheep-derived cathelicidin, has potent activity against several important clinical isolates, including antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Cryptococcus neoformans (21).

Collectively, these studies support a role for cathelicidins in innate immunity and, more specifically, epithelial antimicrobial defense. However, their role in protection against oral infections is unknown. The aim of this study was to test the antimicrobial properties of the cathelicidins FALL39, SMAP29, and CAP18 against various oral bacteria and yeasts.

A broth microdilution assay with modifications for cationic peptides was performed to obtain antimicrobial activity.

All peptides were synthesized, purified, and quantified as previously described (22). The peptides (100 μg/ml) were diluted in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 100 mM NaCl and 3 mg of tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) in polypropylene tubes.

The bacterial strains tested included Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans FDC Y4, Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 49256, Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC W-50, Streptococcus sanguis ATCC 10556, Candida krusei ATCC 6258, Candida tropicalis I11c1T, and Candida albicans ATCC 820. Escherichia coli ATCC 9637 served as a control. The growth conditions for each were as follows: A. actinomycetemcomitans, TSB with 5 μg of vancomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml, 75 μg of bacitracin (Sigma)/ml, and 0.6% yeast extract; F. nucleatum, Schaedler broth (Difco); P. gingivalis, TSB with 5 μg of hemin (Sigma)/ml, 10 μg of menadione (Sigma)/ml, and 0.05% l-Cys HCl (Sigma); S. sanguis, TSB with 0.5% yeast extract; Candida species, YPD broth (Difco); E. coli, nutrient broth (Difco). Cells from early-logarithmic-phase cultures were washed twice in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, resuspended in their respective media, and adjusted to 2.0 × 106 CFU/ml.

Equal volumes of peptide and cells were incubated in microtiter panels (Costar catalog no. 3790; Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) to yield the following final peptide concentrations: 100, 50, 10, 1, and 0.1 μg/ml. Incubations were 0 to 3 h for bacteria and 0 to 24 h for yeast. At 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 3 h, 10-μl aliquots were removed from the panel, diluted, and plated on their respective agar plates. Additional time points of 4, 8, 12, and 24 h were included for yeast strains. CFU/per milliliter were assessed after the cells had grown for 72 h at 37°C under the appropriate aerobic or anaerobic conditions for bacteria and for 48 h on YPD plates under aerobic conditions for yeast. The minimum bactericidal concentration was defined as killing at 99.9% or 3-log10 reduction in CFU/per milliliter. An end point visual screening and spectrophotometric readings (optical density at 650 nm for bacteria and optical density at 490 nm for yeast) were taken for each assay. The peptides were also tested by utilizing two different salt concentrations, 25 (low) and 180 (high) mM, against A. actinomycetemcomitans. The antimicrobial control for all oral bacteria was chlorhexidine gluconate (600 μg/ml) (Alpharma USPD Inc., Baltimore, Md.). The control for E. coli assays was gentamicin (2,000 μg/ml) (Elkins-Sinn, Inc., Cherry Hill, N.J.). The control for yeast assays was fluconazole (500 μg/ml) (Pfizer Inc., Groton, Conn.).

SMAP29 demonstrated the broadest-spectrum bactericidal activity at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μg/ml (Table 1). The most susceptible bacteria were A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, and E. coli, which were killed at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (Table 1 and Fig. 1). C. krusei and C. tropicalis were killed at a concentration of 50 μg/ml (Table 1). Inhibitory activity was seen against S. sanguis and C. albicans beginning at a concentration of 50 μg/ml (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Bactericidal activities of cathelicidins against oral bacteria and yeast

| Species | Strain | MBCa (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FALL39 | CAP18 | SMAP29 | ||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | FDC Y4 | >100 | 50 | 10 |

| F. nucleatum | ATCC 49256 | >100 | 50 | 10 |

| P. gingivalis | ATCC W-50 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| S. sanguis | ATCC 10556 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| C. krusei | ATCC 6258 | >100 | >100 | 50 |

| C. tropicalis | I11clT | >100 | >100 | 50 |

| C. albicans | ATCC 820 | >100 | >100 | 100 |

| E. coli | ATCC 9637 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

MBC, minimum bactericidal concentration, defined as killing at 99.9% or 3-log10 reduction in CFU per milliliter.

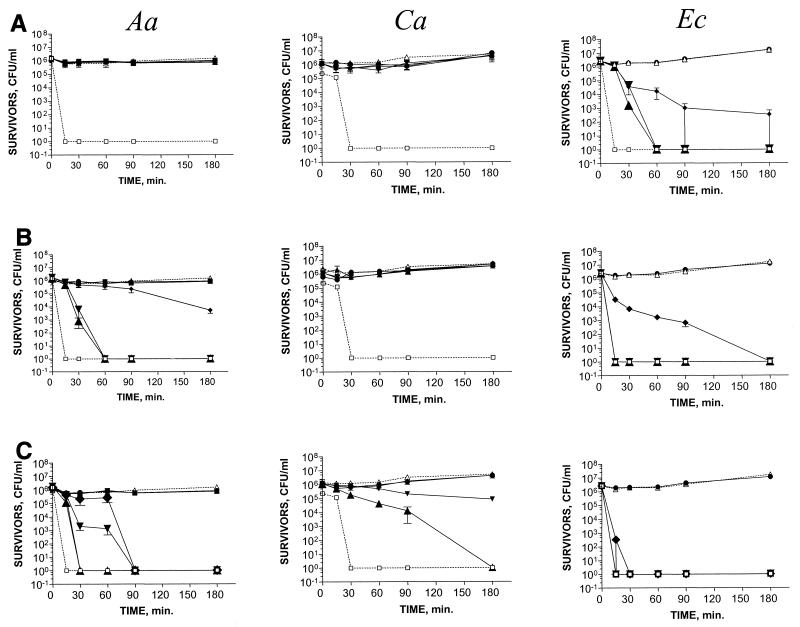

FIG. 1.

Effect of cathelicidins in killing of A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 (Aa), C. albicans 820 (Ca), and E. coli 9637 (Ec) by FALL39 (A), CAP18 (B), and SMAP29 (C). The concentrations of the various peptides were 100 (▴), 50 (▾), 10 (⧫), 1 (●), and 0.1 (■) μg/ml. Control (no peptide) (1176) is also shown. An antimicrobial agent with no peptide control (□) is shown for Aa (chlorhexidine gluconate at 600 μg/ml), for Ca (fluconazole at 500 μg/ml), and for E. coli (gentamicin at 2,000 μg/ml). The points and error bars represent the means and standard deviations (SDδ) of three independent assays.

CAP18 demonstrated bactericidal effects against A. actinomycetemcomitans and F. nucleatum at a concentration of 50 μg/ml (Table 1 and Fig. 1). No significant antimicrobial activity was observed for S. sanguis, P. gingivalis, or the Candida species (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The control organism, E. coli, was killed at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Both CAP18 and SMAP29 were rapidly bactericidal against cultures of A. actinomycetemcomitans and F. nucleatum in the exponential phase of growth. Killing of F. nucleatum occurred within 15 to 30 min. Inhibitory activity against A. actinomycetemcomitans occurred immediately, and bactericidal activity against A. actinomycetemcomitans occurred at 30 and 60 min for SMAP29 and CAP18, respectively (Fig. 1). Inhibitory activity and killing of the Candida species with SMAP29 varied from 30 min to 4 h (Fig. 1 and data not shown). E. coli was killed in 90 min by all three peptides at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (Fig. 1).

FALL39 did not exhibit bactericidal activity against the panel of oral bacteria or yeasts at concentrations less than or equal to 100 μg/ml (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Inhibitory activity of FALL39 (reduction in CFU by 2 log units) was seen in individual assays against P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum at 100 μg/ml (data not shown). The control organism, E. coli, was killed at 10 μg of FALL39/ml (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

The effect of salt on the bactericidal activities of FALL39, CAP18, and SMAP29 was tested against A. actinomycetemcomitans. No differences were seen in the bactericidal efficacies or inhibitory activities of the three peptides with high and low salt concentrations (data not shown).

The rapid inhibition and killing by CAP18 and SMAP29 show promise for use of the peptides as future therapeutics against periodontal organisms and possibly some Candida species. Recently, these same peptides were shown to be the most active against P. aeruginosa, E. coli, S. aureus, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus in a study comparing cathelicidins from five mammals (22).

While little activity was seen for FALL39 in vitro, it may have a more significant impact in vivo, in concert with other innate defense molecules in the oral cavity. Furthermore, the synthetically generated and purified protein utilized in this study may not reflect the processing and function of the active form of the protein in vivo.

The salt concentration did not affect the antimicrobial activities of the peptides. Under inflamed conditions, NaCl concentrations in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid are reported to increase (1, 2). Thus, the cathelicidins may be more useful as therapeutic agents than other antimicrobial peptides produced in the oral cavity, such as neutrophil defensins and β-defensins, which are sensitive to high-salt conditions (7, 16).

Treatment of periodontal disease is challenging due to the polymicrobial etiology. The differential susceptibilities of the organisms seen in this study to the various peptides is not surprising because they differ in cell wall or membrane properties, aerotolerance, and virulence traits (9, 14). Treatment of fungal infections has also become increasingly challenging due to increased resistance of yeast strains to fluconazole and an increase in disease caused by naturally resistant species, such as C. krusei (8, 10, 13, 17). In this study, regrowth of all Candida species was seen after 12 h, confirming the hardiness of these organisms (data not shown).

Human trials are already under way utilizing the cathelin-related protegrins as topical agents for the prevention and treatment of oral ulceration (5). Further consideration of the cathelicidins as therapeutic agents for oral cavity infections will require a better understanding of their antimicrobial efficacies in the oral milieu and their susceptibilities to proteolytic activity inherent in the periodontal lesion (19). They hold therapeutic promise, alone or in combination with existing antimicrobials, for more efficient killing with less probability of creating resistant organisms or undesired side effects.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the differential activities of cathelicidins against clinically important periodontal microorganisms and yeasts. Further research is warranted to evaluate synergistic activities with other innate defenders of the oral cavity. Meanwhile, killing by the cathelicidins suggests a future pharmacological role for these molecules in the treatment and prevention of common oral infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants 1RO1 DE13334 and P30 DE10126.

We are grateful for the scientific discussions with E. P. Greenberg, David Drake, and Kim Brogden relative to this project and the critical reading of the manuscript by Kim Brogden and Sophie Joly. We are grateful to Connie Maze for her comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott B H, Caffesse R G. Crevicular fluid origin, composition, methods of collection, and clinical significance. J West Soc Periodontol. 1977;25:164–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson D B. Salivary electrolytes. In: Tenovuo J O, editor. Human saliva: clinical chemistry and microbiology. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher M A, Kloczewiak M A, Loiselle P M, Ogata M, Vermeulen M W, Zanzot E M, Warren H S. A novel peptide-IgG conjugate, CAP18 (106–138)-IgG, that binds and neutralizes endotoxin and kills gram-negative bacteria. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:621–632. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frohm R W, Agerberth B, Ahangari G, Stahle-Backdahl M, Liden S, Wigzell H, Gudmundsson G. The expression of the gene coding for the antibacterial peptide LL37 is induced in human keratinocytes during inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15258–15263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz T, Weiss J. Antimicrobial peptides of phagocytes and epithelia. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz T, Lehrer R. Antimicrobial peptides of leukocytes. Curr Opin Hematol. 1997;4:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman M J, Anderson G M, Stolzenberg E D, Kari U P, Zasloff M, Wilson J. Human β-defensin-1 is a salt-sensitive antibiotic in lung that is inactivated in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1997;88:553–560. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heald A E, Cox G M, Schell W A, Bartlett J A, Perfect J R. Oropharyngeal yeast flora and fluconazole resistance in HIV-infected patients receiving long-term continuous versus intermittent fluconazole therapy. AIDS. 1996;10:263–268. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hristova K, Selsted M E, White S H. Critical role of lipid composition in membrane permeabilization by rabbit neutrophil defensins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24224–24233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy M J, Calderone R A, Cutler J E, Kanabe T, Riesselman M H, Robert R, Senet J M, Annaix V, Bouali A, Mahaza C. Molecular basis of Candida albicans adhesion. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30(Suppl. 1):95–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamkin M S, Oppenheim F G. Structural features of salivary function. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:251. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larrick J W, Hirata M, Shimomoura Y, Yoshida M, Zheng H, Zhong J, Wright S C. Rabbit CAP18 derived peptides inhibit gram negative and gram positive bacteria. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1994;388:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law D, Moore C B, Wardle H M, Ganguli L A, Keaney M G, Denning D W. High prevalence of antifungal resistance in Candida spp. from patients with AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:659–668. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehrer RI, Barton A, Daher K A, Harwig S S, Ganz T, Selsted M E. Interaction of human defensins with Escherichia coli. Mechanism of bactericidal activity. J Clin Investig. 1989;84:553–561. doi: 10.1172/JCI114198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy O. Antibiotic proteins of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Eur J Haemotol. 1996;56:263–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1996.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyasaki K T, Bodeau A L, Ganz T, Selsted M E, Lehrer R I. In vitro sensitivity of oral, gram-negative, facultative bacteria to the bactericidal activity of human neutrophil defensins. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3934. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3934-3940.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman S L, Flanigan T P, Fisher A, Rinaldi M G, Stein M, Vigilante K. Clinically significant mucosal candidiasis resistant to fluconazole treatment in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:684–686. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson-Frohm M, Sandstedt B, Sorenson O, Weber G, Borregaard N, Stahle-Backdahl M. The human cationic antimicrobial protein (hCAP18), a peptide antibiotic, is widely expressed in human squamous epithelia and colocalizes with interleukin-6. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2561–2566. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2561-2566.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page R C. Host response tests for diagnosing periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1992;63:356–366. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenkels L C, Veerman E C, Nieuw Amerongen A V. Biochemical composition of human saliva in relation to other mucosal fluids. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:161. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skerlavaj B, Benincasa M, Risso A, Zanetti M, Gennaro R. SMAP-29: a potent antibacterial and antifungal peptide from sheep leukocytes. FEBS Lett. 1999;463:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Travis S M, Anderson N N, Forsyth W R, Espiritu C, Conway B D, Greenberg E P, McCray P B, Jr, Lehrer R I, Welsh M J, Tack B F. Bactericidal activity of mammalian cathelicidin-derived peptides. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2748–2755. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2748-2755.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner J, Cho Y, Dinh N N, Waring A J, Lehrer R I. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2206–2214. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinrauch Y, Foreman A, Shu C, Zarember K, Levy O, Elsbach P, Weiss J. Extracellular accumulation of potently microbicidal/bactericidal/ permeability-increasing protein and p15s in an evolving sterile rabbit peritoneal inflammatory exudate. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:1916–1924. doi: 10.1172/JCI117873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittaker C J, Klier C M, Kolenbrander P E. Mechanisms of adhesion by oral bacteria. Annu Rev Micobiol. 1996;50:513–552. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]