Abstract

Objectives

The aims of this study were: (1) to evaluate the genotype calling of several approaches in a high homology region of chromosome 19 (including CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, CYP2B6), and (2) to use this data to investigate associations of two common 3’-UTR CYP2A6 variants, CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733, with CYP2A6 activity in vivo.

Methods

(1) Individuals (n=1704) of European and African ancestry were phenotyped for the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), an index of CYP2A6 activity. Individuals were also genotyped/sequenced using various approaches (deep amplicon exon sequencing, SNP array, genotype imputation, targeted capture sequencing). Amplicon exon sequencing, after realignment to a reference chromosome 19 with CYP2A7 masked, was used as the gold standard. Genotype calls from each method were compared within-individual to those from the gold standard for the exons of CYP2A6, CYP2A7 (exons 1 and 2), CYP2A13, and CYP2B6. Individual data was combined to identify genomic positions with high discordance.

(2) Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association of CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotypes (coded additively) with the log-transformed NMR (logNMR).

Results

(1) Overall, all approaches were ≤2.6% discordant with the gold standard, with discordant calls concentrated at relatively few genomic positions. Fifteen genomic positions were discordant with the gold standard in >10% of individuals, with 12 appearing in regions of perfect or near-perfect identity between homologous genes (e.g. CYP2A6 and CYP2A7). A subset of positions (6/15) showed discrepancies between study major allele frequencies and those reported by online databases, suggesting similar errors in online sources.

(2) In the European-ancestry group (n=935), both the CYP2A6*1B genotype and the rs8192733 genotype were associated with logNMR (p=<0.001). A combined model found main effects (p<0.05) of both variants on increasing logNMR. Similar trends were found in those of African ancestry (n=506), but analyses were underpowered.

Conclusions

Multiple genetic approaches used in this chromosome 19 region contain common identified genotyping/sequencing errors, as do online databases. Design of gene-specific primers and SNP array probes must consider the substantial gene homology; simultaneous sequencing of related genes using short reads in a single reaction should be avoided in order to prevent unresolvable misalignments. Using improved sequencing approaches we characterized two gain of function 3’-UTR variants, including the relatively understudied rs8192733.

Keywords: Pharmacogenetics, CYP2A6, sequencing, nicotine metabolite ratio, 3’-UTR, smoking

Introduction

Cigarette smoking remains a public health problem worldwide, responsible for approximately 8 million deaths annually [1,2]. The main psychoactive agent in cigarettes is nicotine [3]. CYP2A6 is a genetically polymorphic enzyme responsible for the majority of nicotine metabolic inactivation to cotinine, and exclusively for cotinine to 3’-hydroxycotinine (3’-HC)[4]. The ratio of 3’-HC to cotinine in regular smokers is an established CYP2A6 activity biomarker, the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR)[5]. CYP2A6’s major role in nicotine clearance results in the NMR predicting numerous smoking behaviours; for example, higher NMR is associated with higher cigarettes/day, cigarette craving, and lung cancer risk[6–8].

NMR is an effective CYP2A6 phenotype in regular smokers, but not for non-, intermittent- or former-smokers where cotinine and 3’-HC concentrations are not at steady state. Recently, CYP2A6 weighted genetic risk scores (wGRS) were developed in European-ancestry (EUR) and African-ancestry (AFR) individuals[9,10]. In EUR, the wGRS includes seven CYP2A6 variants explaining ~34% of NMR variation. In AFR, the wGRS includes 11 CYP2A6 variants explaining ~30–35% of NMR variation. Three wGRS variants are common to both. These wGRS recapitulate NMR associations with smoking behaviours and cessation[9,10].

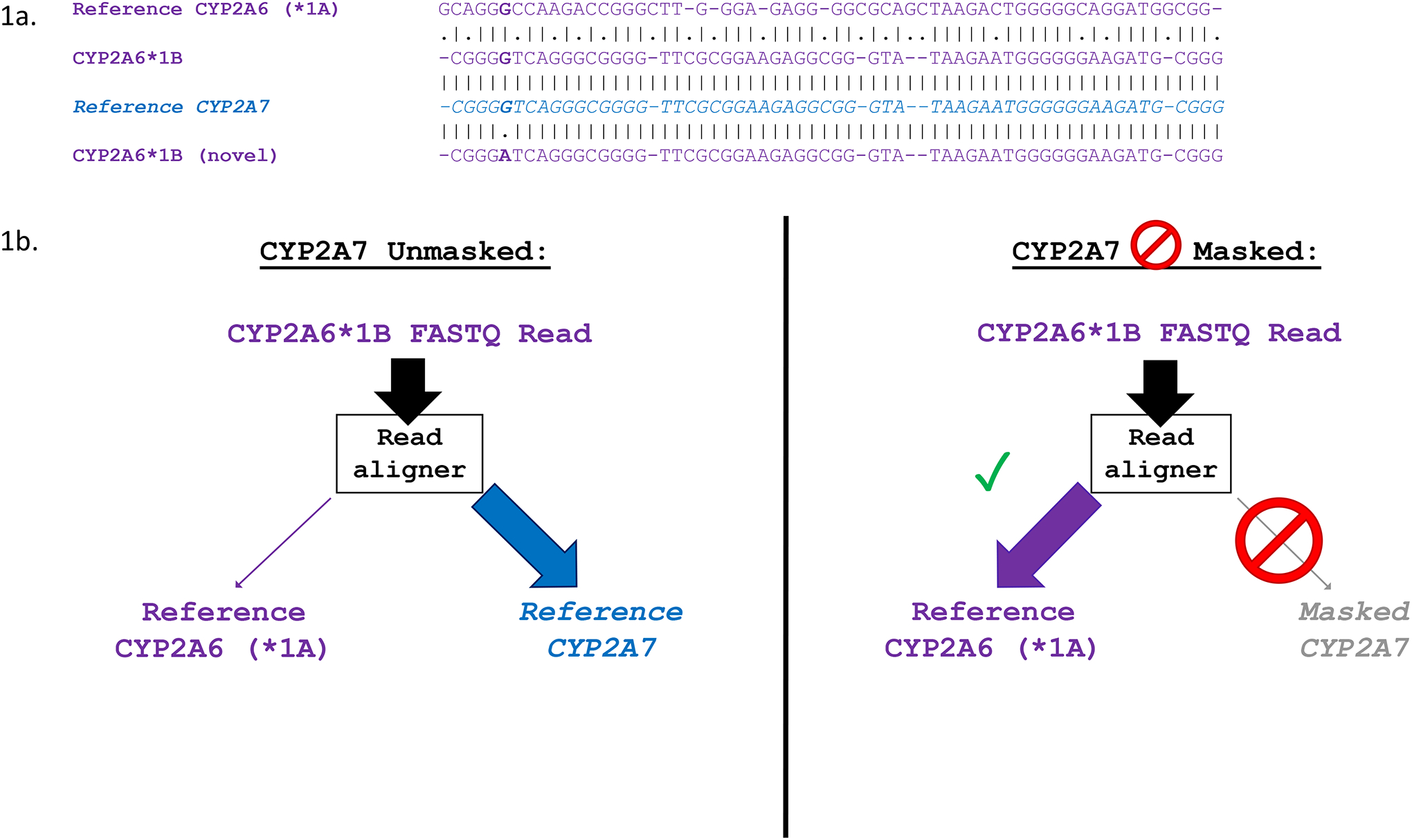

wGRS utility depends on accurate CYP2A6 genotyping, which is difficult due to homology between CYP2A6, the pseudogene CYP2A7 (i.e. 96% nucleotide identity) and CYP2A13[11]. Furthermore, variants defined by a conversion of CYP2A6 to CYP2A7 can cause 100% nucleotide identity between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7; for example, CYP2A6*1B leads to 100% identity for the first ~150 bp of the 3’-UTR (Figure 1a). While NMR heritability estimates in EUR are 60–80%, the wGRS explains ~34% of NMR variation and a meta-GWAS explained 38% [12–14]. Some of the missing heritability may come from inaccurate genotyping, rare variants, and variants not captured in GWAS (e.g. structural variants).

Figure 1. CYP2A6*1B’s identity with CYP2A7 leads to spurious read alignments which can be resolved by masking CYP2A7.

a. Multiple sequence alignment showing the 3’-UTR of CYP2A6*1A (NG_008377.1: 11700–11758; GRCh37: 41349653–41349595), CYP2A6*1B, WT CYP2A7 (NG_007960.1: 12108–12165; GRCh37: 41381550–41381493), and a newly discovered allele of CYP2A6*1B (CYP2A6*1B (novel)). Vertical dashes between alignments indicate identity, while dots indicate non-identical sequence. b. Alignment of CYP2A6*1B reads with and without masking of CYP2A7. Without masking of CYP2A7, CYP2A6*1B FASTQ reads are interpreted by the read aligner as CYP2A7, and are incorrectly aligned to the 3’-UTR of CYP2A7 during .bam file generation. Masking of CYP2A7 forces alignment of CYP2A6*1B reads to CYP2A6, allowing for accurate genotype calling.”

Here we conducted the first locus-wide assessment of the accuracy of various CYP2A6 genotyping and sequencing approaches. We leveraged data from the Pharmacogenetics of Nicotine Addiction and Treatment (PNAT)-2 smoking cessation clinical trial (NCT01314001)[15]. Our final sample comprised 935 EUR and 506 AFR individuals who were genotyped and sequenced for CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6 using Illumina array genotyping, amplicon exon sequencing, and targeted capture full-gene sequencing, providing a unique opportunity to compare genotype calls between methods.

Our first aim was to compare genotype calls for various approaches against a gold standard (amplicon exon sequencing) to identify areas of discordance which may interfere with CYP2A6 studies. As a second aim, we applied this to examine variation within the 3’-UTR of CYP2A6. CYP2A6*1B is a common allele in both EUR and AFR, containing a 58 bp stretch of CYP2A7 sequence within the 3’-UTR. CYP2A6*1B is associated with higher CYP2A6 activity in EUR but is difficult to identify (CYP2A6*1B is not catalogued on dbSNP, dbVar, or other online databases) without using gene-specific genotyping methods, due to its section of 100% identity with CYP2A7 [16,17]. The 58 bp conversion may confer higher mRNA stability, potentially through an interaction with the mRNA-binding protein HNRNPA1[18]. In addition to CYP2A6*1B, we examined rs8192733, another common CYP2A6 3’-UTR variant located within the putative HNRNPA1 binding site ~50 bp downstream of CYP2A6*1B. A recent in vivo study found an association between rs8192733 and higher CYP2A6 activity[18,19]. Due to its proximity to CYP2A6*1B and presence within a region of nucleotide identity between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7, rs8192733 is also difficult to genotype accurately. Thus, we investigated genotyping accuracy of CYP2A6*1B, rs8192733, and their association with the NMR.

Methods

Study Population

Participants from PNAT2 (NCT01314001) provided blood collected during ad libitum smoking for DNA and NMR assessment[15]. We measured 3’-HC and cotinine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to derive NMR, as described[15]. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all clinical sites (University of Pennsylvania, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, MD Anderson, SUNY Buffalo) and the University of Toronto. Genetic ancestry was examined in 1704 individuals using multidimensional scaling in combination with data from HapMap3[20]. We analyzed participants of genetically European-ancestry (EUR; n=935) and African-ancestry (AFR; n=506); genetic and self-reported ancestries were highly concordant (96.8% in EUR and 98.5% in AFR)[9].

Genomic Assessments

Genetic data were obtained using six approaches, described in Table 1 (graphical summary in Figure 2):

Table 1.

Description of genetic data Approaches 1–6

| Approach | Sample | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Approach 1 (A1) Amplicon Exon Sequencing | EUR n=935; AFR n=506 | The sample was exon sequenced using deep amplicon sequencing targeting all exons of CYP2A6, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6, and exons 1–2 of CYP2A7, as described previously[9, 38]. Insert sizes were 262–475 bp, and paired read lengths were 2×248 bp. Sanger sequencing in a sample of 120 Japanese individuals was used to validate the exon sequencing approach and yielded 100% concordance[38]. Thus, A1 was used as the “gold standard” for exonic variant calls in subsequent analyses. Initial inspection of .bam sequence alignment files showed unexpectedly low read depth at CYP2A6 exon 9 and high read depth at CYP2A7 exon 9 (which was not targeted); the same was observed for CYP2B6 exons 4–5, with high read depth at CYP2B7 exons 4–5 (also not targeted). We speculated that these were spurious alignments due to gene homology. For example, the variant CYP2A6*1B allele results in the CYP2A6 3’-UTR being identical to the 3’-UTR of CYP2A7, potentially causing a misalignment of CYP2A6*1B reads to CYP2A7 sequence (Figure 1a). To address the spurious calls, re-alignment was performed using Bazam[39]. Sequence alignment .bam files were re-aligned to a modified reference chromosome 19, with CYP2A7 exons 3–9 masked (i.e. sequence replaced with placeholder “N” characters) using bedtools maskfasta (Figure 1b)[40]. Variant calling was then performed on the resulting .bam files using GATK HaplotypeCaller, yielding VCF files[41]. Post-CYP2A7 exon 3–9 masking, and realignment, CYP2A6*1B calls were compared to internal genotyping of the variant using Sanger sequencing; concordance was ~97% (internal data), confirming that spurious alignment of CYP2A6*1B reads to CYP2A7 sequence resulted in the poor genotype calling. The same masking and realignment technique was used for all CYP2B7 exons to prevent spurious alignment of CYP2B6 exon 4–5 reads to CYP2B7. |

| Approach 2 (A2) SNP Array | EUR n=935; AFR n=506 | Individuals were genotyped using the Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome-8 version 1.2 SNP array with >2500 additional variants added on; additions were in areas known to be associated with nicotine metabolism or smoking behaviours (e.g. CYP2ABFGST cluster on chromosome 19). A full list of added variants and a description of QC procedures are available elsewhere; array markers failing Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium tests were removed[20]. Output files in PLINK binary format (.bed/.bim/.fam) were converted to VCF files using PLINK v1.9[21]. |

| Approach 3 (A3) Haplotype Reference Consortium Panel Imputation | EUR n=935 | Missing genotypes were imputed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) Version 1.1 reference panel based on SNP array data from A2 using the Michigan Imputation Server, as described previously[42]. |

| Approach 4 (A4) 1000G Imputation | AFR n=506 | Missing genotypes were imputed using the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 reference panel based on SNP array data from A2 using the Michigan Imputation Server. |

| Approach 5 (A5) TOPMED Imputation | AFR n=506 | In a separate round of imputation, missing genotypes in AFR were imputed using the TOPMED reference panel based on SNP array data from A2 using the TOPMED Imputation Server[43]. |

| Approach 6 (A6) Targeted Capture Sequencing | EUR n=209; AFR n=166 | A subset of the total sample (n=209 EUR and n=166 AFR) were sequenced for the entire genomic region containing CYP2A6, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6 (including intergenic regions and introns from GRCh37 chr19:41322500–41615000). A custom hybridization target capture design next-generation sequencing (NGS) method was used, as described previously[18]. Paired-end read lengths were 2×151 bp. |

1000G: 1000 Genomes Project; AFR: African-ancestry individuals; EUR: European-ancestry individuals; HRC: Haplotype Reference Consortium; QC: Quality Control

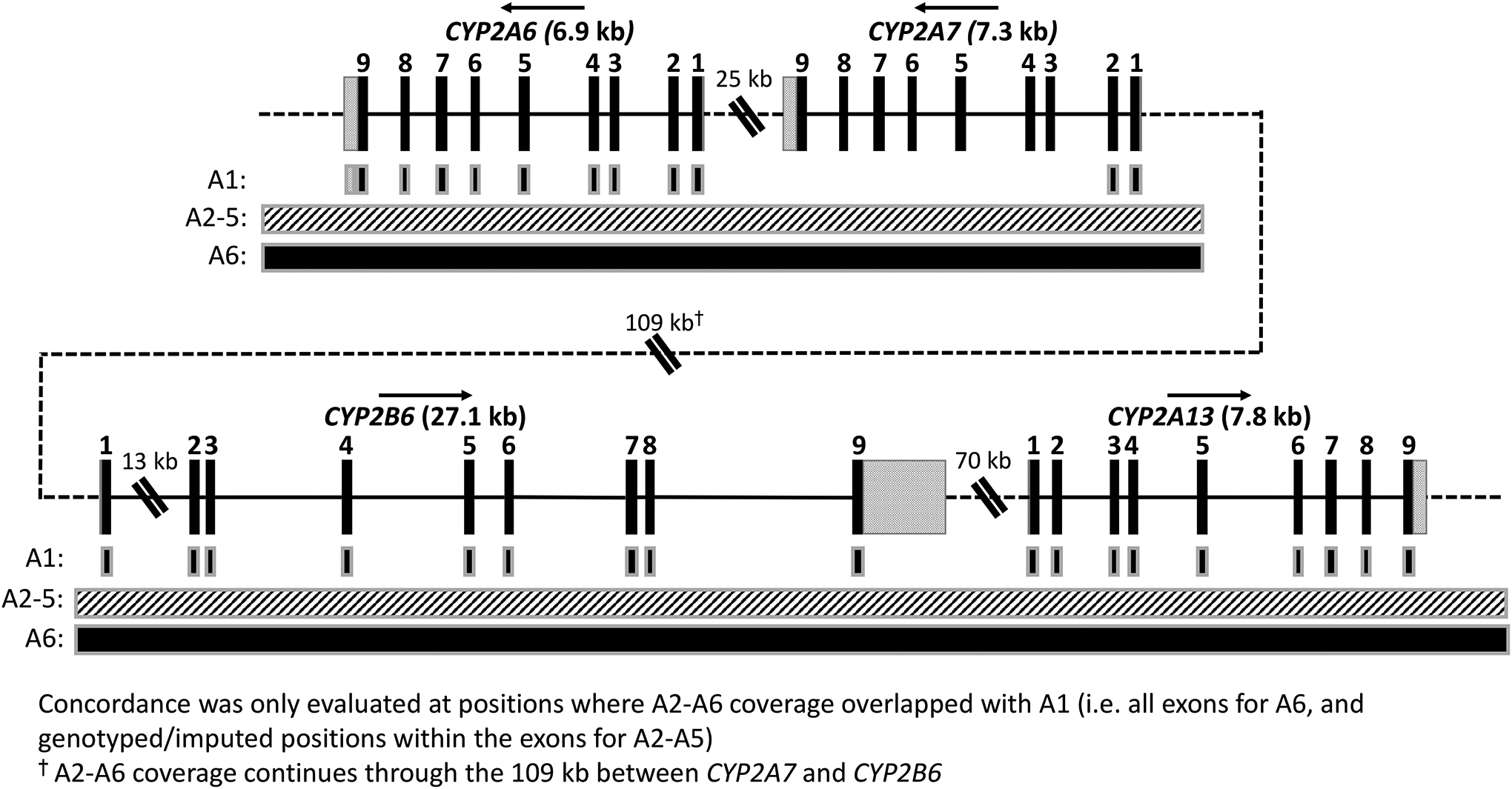

Figure 2. Coverage of approaches A1–6 through CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2B6, and CYP2A13.

The four genes analyzed in this study are indicated by name; arrows above the gene name indicate direction of transcription (genomic position according to GRCh37 is shown increasing from left-to-right). DNA sequence within genes is shown as a solid black line, while intergenic sequence is shown as a dotted line (not to scale). Exons are shown as black rectangles with exon number indicated above, while the 5’- and 3’-UTRs are shown as grey speckled rectangles attached to exons 1 9, respectively. Gene exons, introns (except CYP2B6 intron 1), and UTRs are displayed to scale; double diagonal bars indicate shortened sequence (not to scale). The 109 kb gap between CYP2A7 and CYP2B6 contains the pseudogenes CYP2B7 and CYP2G1P (not shown), while the 70 kb gap between CYP2B6 and CYP2A13 contains CYP2A7P1 and CYP2G2P (not shown). A1 coverage, indicated by black boxes with grey outlines, is limited to the exons in addition to partial coverage of the CYP2A6 3’-UTR (used for genotyping of CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 in Experiment 2). A2-A5, indicated by a continuous box with a white/grey hatched pattern, covers a limited number of positions for the entire region. A6, indicated by a continuous black box with a grey outline, continuously covers ~300 kb which encompasses the entire region presented.

Approach 1 (A1) Amplicon Exon Sequencing

Approach 2 (A2) SNP Array

Approach 3 (A3) Haplotype Reference Consortium Panel Imputation

Approach 4 (A4) 1000G Imputation

Approach 5 (A5) TOPMED Imputation

Approach 6 (A6) Targeted Capture Sequencing

Analyses of Discordance Between Approaches

A1 was chosen as a gold standard for discordance analyses after validation through Sanger sequencing and Taqman SNP genotyping assays [38]. Analyses of discordant exon calls between A1 and A2-A6 were conducted pairwise using hap.py (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). VCF files of exon calls from Approaches 2–6 were used as “query” files in hap.py, and compared to A1 VCF files for the same individual. Output by individual was combined to determine overall discordant calls by method and genomic position (Supplemental Methods). All highly (>10%) discordant positions were evaluated for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using PLINK 1.9 [21].

CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 Characterization

A1 amplicon exon sequencing captured a portion of 3’-UTR sequence for all participants, allowing for calling of CYP2A6*1B (Figure 1a) and rs8192733 (GRCh37 19:41349550 C>G). Herein, “CYP2A6*1B” includes all CYP2A6*1B suballeles as they do not include structural or amino acid sequence-changing variants (see: pharmvar.org) [24]. Other star alleles including the 3’-UTR conversion characteristic of CYP2A6*1B (e.g. CYP2A6*24) were excluded. Analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) was performed using PLINK2[21]. VCF files for participants were phased using Whatshap 1.1[22], then converted to .pgen/.pvar/.psam files using PLINK2[21]. The “--ld” option in PLINK2 was used to generate summary LD statistics.

Genotyping of CYP2A6 Structural and non-exonic star alleles

Participants were previously genotyped for known CYP2A6 structural variants (CYP2A6*12, CYP2A6*1×2, and CYP2A6*4) using Taqman copy number assays (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) [23]. A1 amplicon exon sequencing captured a portion of the 5’-UTR, allowing for genotyping of CYP2A6*9 (rs28399433; TATA box variant).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software) and SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corporation) using a statistical significance threshold of p<0.05. The NMR was log-transformed for analysis. Linear regression assessed the contribution of CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 to variability in logNMR in participants with no known SNP or structural variant CYP2A6 star alleles, as listed on pharmvar.org, or other non-synonymous CYP2A6 variants[24]; the final analytic sample, after exclusion of individuals with variant alleles, was stratified into EUR (n=597) and AFR (n=208) groups. CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotypes were coded additively (i.e. 0, 1, 2 variant copies). Linear regression models were adjusted for known NMR covariates (age, BMI, and sex[25]). Separate linear regression analyses were performed in all participants, including those with additional variant alleles (EUR n=930, n=5 individuals excluded due to lack of NMR data; AFR n=504, n=2 individuals excluded due to lack of NMR data). We controlled for the presence of additional SNP or structural variant star alleles and other non-synonymous variants (i.e. those with and without variants were coded as 1 and 0, respectively). Linear regression models were checked for residual normality. All models failed Shapiro-Wilk tests, but Q-Q plots suggested approximate normality (Supplemental Figure 1). Using rank-based inverse normal transformation of NMR resulted in similar results to models using logNMR, suggesting sufficient normality (Supplemental Table 1).

Results

Overall Discordance

The number of positions evaluated by each approach differed based on the number of individuals genotyped or sequenced, and the number of array genotyped positions, imputed positions, or sequenced positions within the exons of CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of A2–6 discordance with A1 Amplicon Exon Sequencing calls in CYP2A6, CYP2A7 (exons 1–2), CYP2A13, and CYP2B6

| Approach | # of samples | # of Genotyped Positions | Total Callsa | Discordant Calls (vs. A1)b | Discordance Rate (vs. A1)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Amplicon Exon Sequencing (EUR+AFR) | 1441c | 4789 | 6900949c | N/Ad | N/Ad |

| A2 SNP Array (EUR) | 935 | 6 | 5610 | 85 | 1.5% |

| A2 SNP Array (AFR) | 506 | 15 | 7590 | 199 | 2.6% |

| A3 HRC Imputation (EUR) | 935 | 49 | 45815 | 267 | 0.6% |

| A4 1000G Imputation (AFR) | 506 | 172 | 87032 | 547 | 0.6% |

| A5 TOPMED Imputation (AFR) | 506 | 160 | 80960 | 1040 | 1.3% |

| A6 Targeted Capture Sequencing (EUR) | 209 | 4789 | 1000901 | 382 | 0.04% |

| A6 Targeted Capture Sequencing (AFR) | 166 | 4789 | 794974 | 280 | 0.04% |

Calculated by # of samples x # of genotyped positions

(see supplemental methods for details on calculations)

Within the 1441 samples (935 EUR and 506 AFR), 13601 variant calls were made. 13585 (99.9%) passed GQ≥20 (i.e. 99% or greater confidence in variant calls); all 13601 calls passed QUAL≥20

Not applicable, as A1 is the reference to which other approaches are compared

1000G: 1000 Genomes Project; AFR: African-ancestry individuals; EUR: European-ancestry individuals; GQ: Phred-scaled confidence that the genotype call is correct (GQ=20 indicates 99% confidence); HRC: Haplotype Reference Consortium; QUAL: Phred-scaled confidence that there is variation at the specified position (QUAL=20 indicates 99% confidence)

All approaches were discordant at ≤2.6% of total positions, with A2 SNP array in AFR being most discordant (2.6% discordance) and A6 targeted capture sequencing in EUR (0.04% discordance) and AFR (0.04% discordance) being least discordant (Table 2).

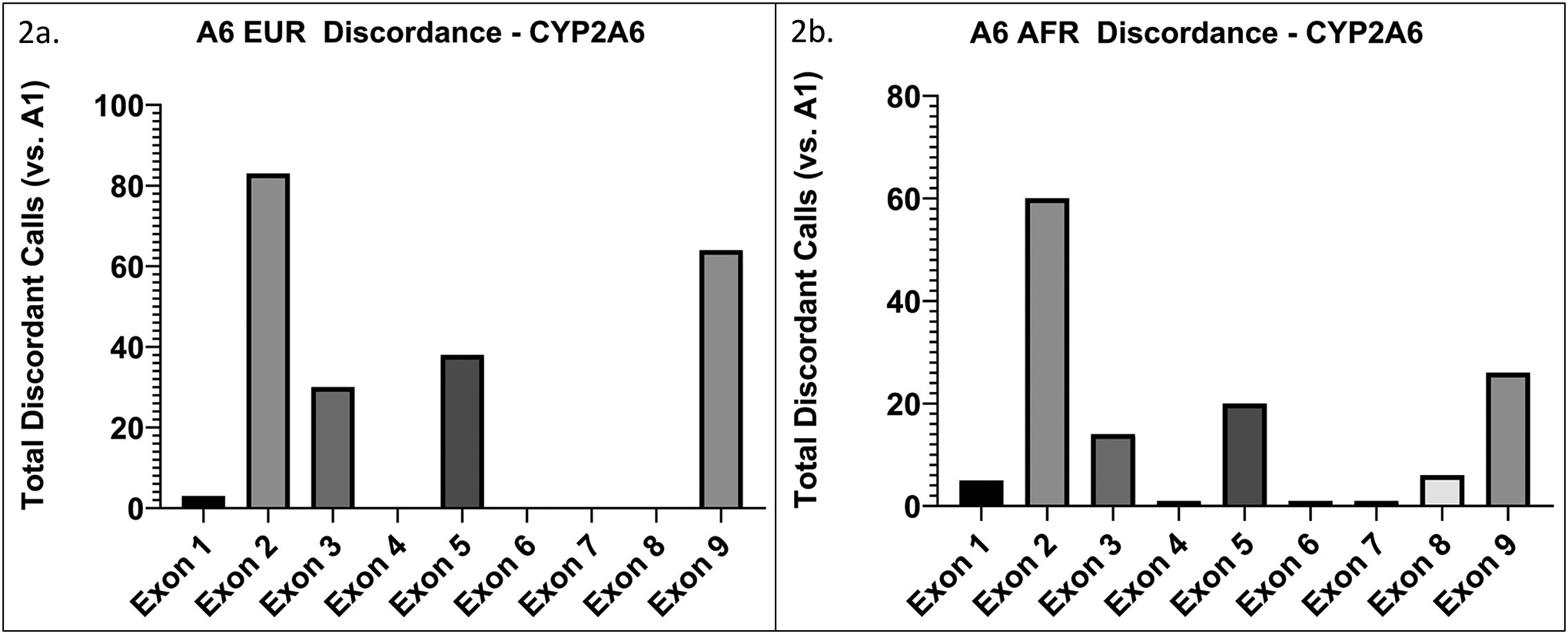

For the two sequencing approaches (A1 and A6), all exonic positions were sequenced, thus discordance rate was further investigated by exon in CYP2A6. In EUR, 38% of the 218 discordant calls were within exon 2, 14% were in exon 3, 17% were in exon 5, and 29% were in exon 9; only ~2% of discordant calls were within exons 1, 4, or 6–8 (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Discordant calls between A6 targeted capture sequencing and A1 amplicon exon sequencing in CYP2A6 are concentrated in specific exons.

The y-axis represents total discordant calls (i.e. the sum of all discordant calls within each exon across the group) within each exon for a. EUR (n=209), and b. AFR (n=166). Discordant calls in exons 2, 3, 5, and 9 make up ~90% of overall CYP2A6 discordant calls in EUR and AFR.

In AFR, 45% of the 134 discordant calls in CYP2A6 were within exon 2, 10% were in exon 3, 15% were in exon 5, and 19% were in exon 9; only ~10% of discordant calls were within exons 1, 4, or 6–8 (Figure 3b).

Positions of High Discordance

Positions where >10% of individuals were discordant between Approaches 2–6 and A1 (i.e. the gold standard approach) were deemed highly discordant and investigated further. A total of 15 highly discordant positions were identified; all were found within CYP2A6, CYP2A7, or CYP2B6 (Table 3). Sanger sequencing validation was performed at one of the 15 highly discordant positions, rs2002977, in 120 Japanese individuals; concordance with A1 was 100%.

Table 3.

Summary of highly discordant positions (>10% of samples discordant when compared to A1 Exon Sequencing)

| Approach | Chr19 Position (GRCh37) | rsid | Ref>Var | Gene | Exon | Known * allele | SNP Type | Error Type | Wrong Calls/# of samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 (AFR) + A4 | 41349750 | rs5031017 | C>A | CYP2A6 | 9 | CYP2A6*5 | Missense | FP | A2: 170/506 A4: 172/506 |

| A3 | 41354533 | rs1801272 | A>T | CYP2A6 | 3 | CYP2A6*2 | Missense | Mostly FP | 182/935 |

| A5 | 41350648 | rs28399461 | A>G | CYP2A6 | 8 | N/A | Synonymous | Mostly FN | 57/506 |

| A5 | 41350582 | rs8192730 | C>G | CYP2A6 | 8 | CYP2A6*28 | Missense | Mostly FP | 93/506 |

| A5 | 41350587 | rs28399463 | T>C | CYP2A6 | 8 | CYP2A6*28 | Missense | Mostly FP | 146/506 |

| A5 | 41350594 | rs2002977 | G>A | CYP2A6 | 8 | N/A | Synonymous | FP | 216/506 |

| A5 | 41387620 | rs10425150 | A>G | CYP2A7 | 2 | N/A | Synonymous | Mostly FP | 49/506 |

| A5 | 41387647 | rs10425169 | A>G | CYP2A7 | 2 | N/A | Missense | Mostly FP | 54/506 |

| A5 | 41387656 | rs10425176 | A>T | CYP2A7 | 2 | N/A | Missense | Mostly FP | 52/506 |

| A6 (AFR) | 41349786 | rs145014075 | G>T | CYP2A6 | 9 | N/A | Stop-gain | FP | AFR: 22/166 |

| A6 (EUR) | 41349874 | rs143731390 | T>A | CYP2A6 | 9 | CYP2A6*35 | Missense | FP | EUR: 44/209 |

| A6 (EUR) | 41352807 | rs55805386 | A>C | CYP2A6 | 5 | N/A | Synonymous | FP | EUR: 37/209 |

| A6 (EUR+AFR) | 41355849 | rs2302990 | A>G | CYP2A6 | 2 | N/A | Synonymous | FP | EUR: 73/209 AFR: 58/166 |

| A6 (EUR+AFR) | 41515192 | rs376359134 | G>A | CYP2B6 | 5 | N/A | Synonymous | FN | EUR: 87/209 AFR: 39/166 |

| A6 (EUR) | 41515263 | rs2279343 | A>G | CYP2B6 | 5 | CYP2B6*4 | Missense | FN | EUR: 45/209 |

AFR: African-ancestry individuals; EUR: European-ancestry individuals; FN: False Negative; FP: False positive;

Nine of the 15 highly discordant positions contained missense or stop-gain variants, and six contained variants characterizing known functional star alleles (Table 3)[24].

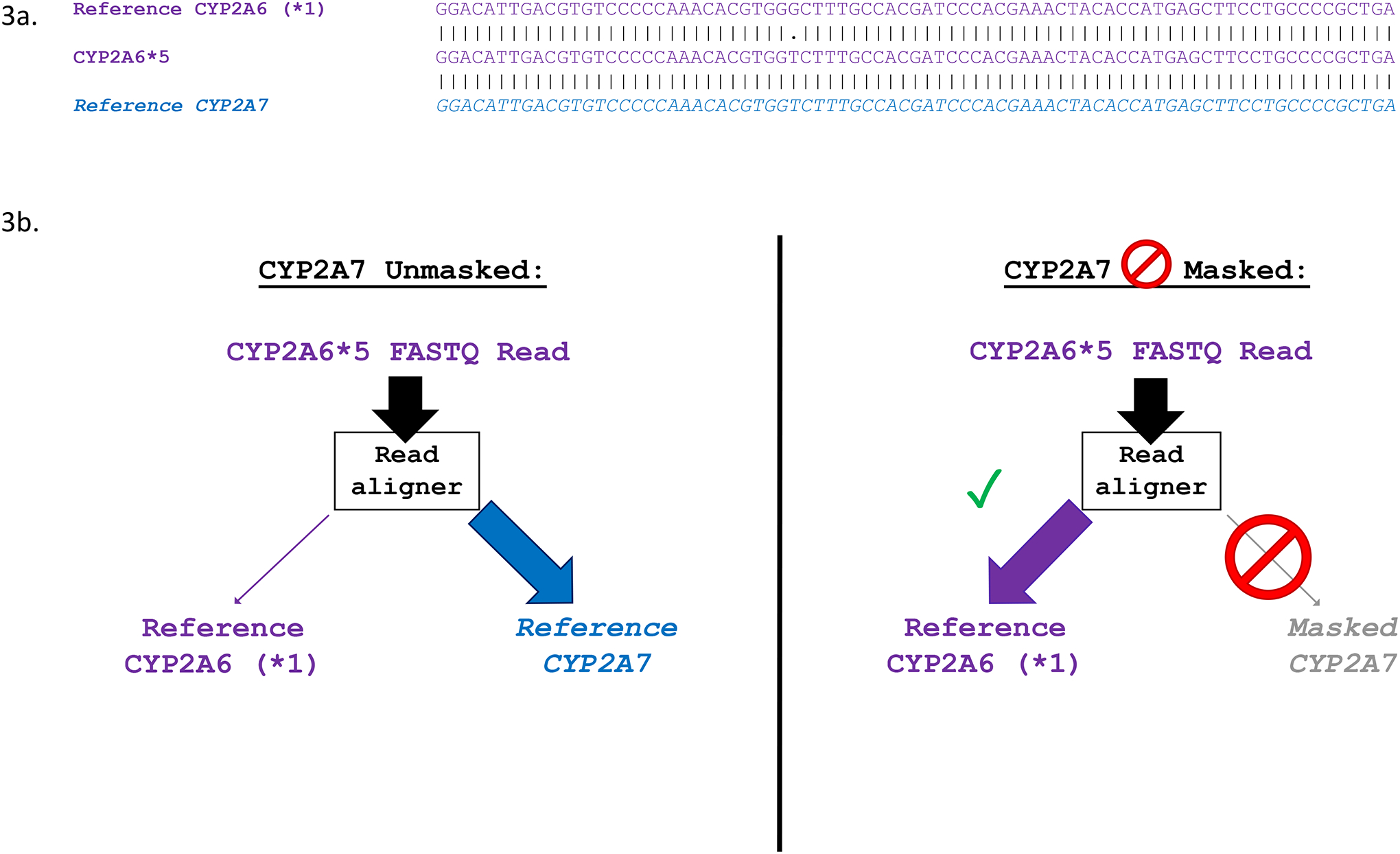

We investigated the genomic contexts of the 15 highly discordant positions. Four of the 15 highly discordant positions were located in regions of high homology (100% nucleotide identity +/−20 bp), where the variant alleles in CYP2A6 or CYP2B6 match the reference alleles at the equivalent positions in CYP2A7 and CYP2B7, respectively. Specifically, one of these four positions (rs5031017), which was discordant in A2 and A4, was found in a long region containing perfect nucleotide identity between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 in exon 9. The CYP2A6 variant at rs5031017 is C>A (leading to CYP2A6*5), and the reference allele at the equivalent position in CYP2A7 is A; the surrounding sequence is identical between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 (Figure 4). The three other positions were discordant in A6: one other in CYP2A6 (rs55805386), and two in CYP2B6 (rs376359134 and rs2279343).

Figure 4. CYP2A6*5’s identity with CYP2A7 leads to spurious read alignments which can be resolved by masking CYP2A7.

a. Multiple sequence alignment showing exon 9 of CYP2A6*1 (NG_008377.1: 11574–11652; GRCh37: 41349779–41349701), CYP2A6*5, and WT CYP2A7 (NG_007960.1: 11982–12060; GRCh37: 41381676–41381598). Vertical dashes between alignments indicate identity, while dots indicate non-identical sequence. b. Alignment of CYP2A6*5 reads with and without masking of CYP2A7. Without masking of CYP2A7, CYP2A6*5 reads are interpreted by the read aligner as CYP2A7, and are incorrectly aligned to exon 9 of CYP2A7 during .bam file generation. Masking of CYP2A7 forces alignment of CYP2A6*5 reads to CYP2A6, allowing for accurate genotype calling.

Next, three of the 15 highly discordant positions (rs2002977, rs28399463, rs8192730) in A5 were found within the same 12 bp stretch of sequence in exon 8 of CYP2A6. This stretch appears within a region of high nucleotide identity between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7, with the three variant alleles in CYP2A6 matching the reference alleles at the equivalent positions in CYP2A7.

Four other highly discordant positions (rs143731390, rs145014075, rs10425150, rs10425176) were located in highly identical sequences, but where the reference alleles in CYP2A6/CYP2B6 were the same as the reference alleles at the equivalent positions in CYP2A7/CYP2B7. The last four highly discordant positions (rs1801272, rs8192730, rs2302990, rs10425169) were found within stretches of non-identity. According to A1, the two highly discordant positions within CYP2B6 were not in HWE possibly due to non-specific amplification of CYP2B7 exon 5; the 13 others were in HWE (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of study variant MAF to online database variant MAF for highly discordant positions and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium tests

| Approach | Chr19 Position (GRCh37) | rsid | Ref>Var | Gene | Error Type | Ancestry | A1 HWE p-valuec |

Discordant Approach HWE p-valuec | Study MAFa | ALFA MAFa | 1000G MAFa | gnomAD MAFa,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2+A4 | 41349750 | rs5031017 | C>A | CYP2A6 | FP | AFR | 1 | 0.23 (A2)/ 0.30 (A4) |

0 | 0.0012 | na | 0.00018 |

| A3 | 41354533 | rs1801272 | A>T | CYP2A6 | Mostly FP | EUR | 1 | 0.08 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.034 | 0.027 |

| A5 | 41350648 | rs28399461 | A>G | CYP2A6 | Mostly FN | AFR | 0.28 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| A5 | 41350582 | rs8192730 | C>G | CYP2A6 | Mostly FP | AFR | 1 | 0.0028 | 0.016 | 0.016 | na | 0.0099 |

| A5 | 41350587 | rs28399463 | T>C | CYP2A6 | Mostly FP | AFR | 1 | 0.0033 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.012 |

| A5 | 41350594 | rs2002977 | G>A | CYP2A6 | FP | AFR | 0.82 | 7.3×10 −7 | 0.11 | 0.094 | 0.11 | 0.093 |

| A5 | 41387620 | rs10425150 | A>G | CYP2A7 | Mostly FP | AFR | 0.93 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| A5 | 41387647 | rs10425169 | A>G | CYP2A7 | Mostly FP | AFR | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.32 |

| A5 | 41387656 | rs10425176 | A>T | CYP2A7 | Mostly FP | AFR | 1 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.33 |

| A6 | 41349786 | rs145014075 | G>T | CYP2A6 | FP | AFR | N/Ad | 1 | 0 | 0.011 | na | 0.028 |

| A6 | 41349874 | rs143731390 | T>A | CYP2A6 | FP | EUR | 1 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.031 | na | na |

| A6 | 41352807 | rs55805386 | A>C | CYP2A6 | FP | EUR | 1 | 0.38 | 0.0011 | 0.018 | na | na |

| A6 | 41355849 | rs2302990 | A>G | CYP2A6 | FP | EUR | 1 | 6.0×10 −4 | 0 | 0.010 | na | na |

| AFR | 1 | 0.0027 | 0.0010 | 0.0038 | na | na | ||||||

| A6 | 41515192 | rs376359134 | G>A | CYP2B6 | FN | EUR | 7.5×10 −21 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.013 | na | 0.0016 |

| AFR | 1.7×10 −4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.0038 | na | 0.0017 | ||||||

| A6 | 41515263 | rs2279343 | A>G | CYP2B6 | FN | EUR | 9.8×10 −27 | 1 | 0.36 | 0.23 | na | 0.086 |

MAFs for EUR or AFR according to the “Ancestry” column

Using the gnomAD Exomes dataset

Variants differing significantly (p<0.05) from HWE are bolded

HWE testing was not possible due to MAF=0

1000G: 1000 Genomes Project; AFR: African-ancestry individuals; EUR: European-ancestry individuals; FN: False Negative; FP: False positive; MAF: Minor allele frequency

Highly discordant positions: MAF Comparison to online databases

The minor allele frequency (MAF) at the 15 highly discordant positions was calculated for PNAT2 EUR and AFR based on A1 amplicon exon sequencing data, and compared to EUR and AFR MAFs from the online databases ALFA[26], 1000Genomes[27], and gnomAD[28].

The six positions which were highly discordant in A6 showed MAF differences between our study and online databases (Table 4). Positions where wrong calls were false positives (i.e. overcalling in A6) also had higher MAF in databases vs. A1 (i.e. possible overcalling in online databases); and positions whose wrong calls were false negatives (i.e. under-calling in A6) had lower MAF in databases vs. A1 (i.e. possible under-calling in online databases). The other nine highly discordant positions (discordant in the non-sequencing A2-A5) had similar MAF between A1 and the online databases (Table 4).

CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 Characterization

We next applied our findings on genotyping accuracy by investigating the 3’-UTR of CYP2A6, which is notoriously difficult to genotype[16], in individuals genotyped using A1 amplicon exon sequencing as CYP2A6*1A/*1B and CYP2A6*1B/*1B. One of the n=128 CYP2A6*1B/*1B individuals possessed a variant within the 58 bp conversion. The CYP2A6*1B sequence at the beginning of the conversion is typically GRCh37 19:41349652 GCAGGG>CGGGG; the sequence was GCAGGG>CGGGA in one of the two CYP2A6*1B alleles from this individual (Figure 1a, alignment labeled “CYP2A6*1B (novel)”). Of note, this novel G>A variant was not found within the sequence to which CYP2A6*1B-genotyping primers anneal[29]. All other CYP2A6*1A/*1B (n=629) and CYP2A6*1B/*1B individuals (n=127, i.e. 254 CYP2A6*1B copies) were found to have identical 58 bp conversions (including GCAGGG>CGGGG), matching the 3’-UTR of WT CYP2A7 (Figure 1a, alignment labeled “CYP2A6*1B”).

Data on linkage disequilibrium (LD) between CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 is not accessible in online databases, such as NIH’s LDlink[30], likely due to incorrect alignment of CYP2A6*1B sequence to CYP2A7 in their reference panels. Thus, we calculated LD within our sample. CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 were less highly linked in EUR (r2=0.50; D’=0.94) vs. AFR (r2=0.75; D’=0.93); variants were more frequent in EUR (CYP2A6*1B MAF=0.30, rs8192733 MAF=0.43) than in AFR (CYP2A6*1B MAF=0.17, rs8192733 MAF=0.19). Approximately 55% and 80% of alleles were CYP2A6*1A with C (the reference base at rs8192733) in EUR and AFR, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Linkage disequilibrium summary statistics and CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 allele frequencies in EUR and AFR individuals

| EUR (n=935); D’=0.94; R2=0.50 | ||

|---|---|---|

| CYP2A6*1A | CYP2A6*1B | |

| rs8192733 Reference (C) | 56% | 1% |

| rs8192733 Variant (G) | 14% | 29% |

| AFR (n=506); D’=0.93; R2=0.75 | ||

| CYP2A6*1A | CYP2A6*1B | |

| rs8192733 Reference (C) | 80% | 1% |

| rs8192733 Variant (G) | 3% | 16% |

AFR: African-ancestry individuals; EUR: European-ancestry individuals

CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 Associations with CYP2A6 Activity

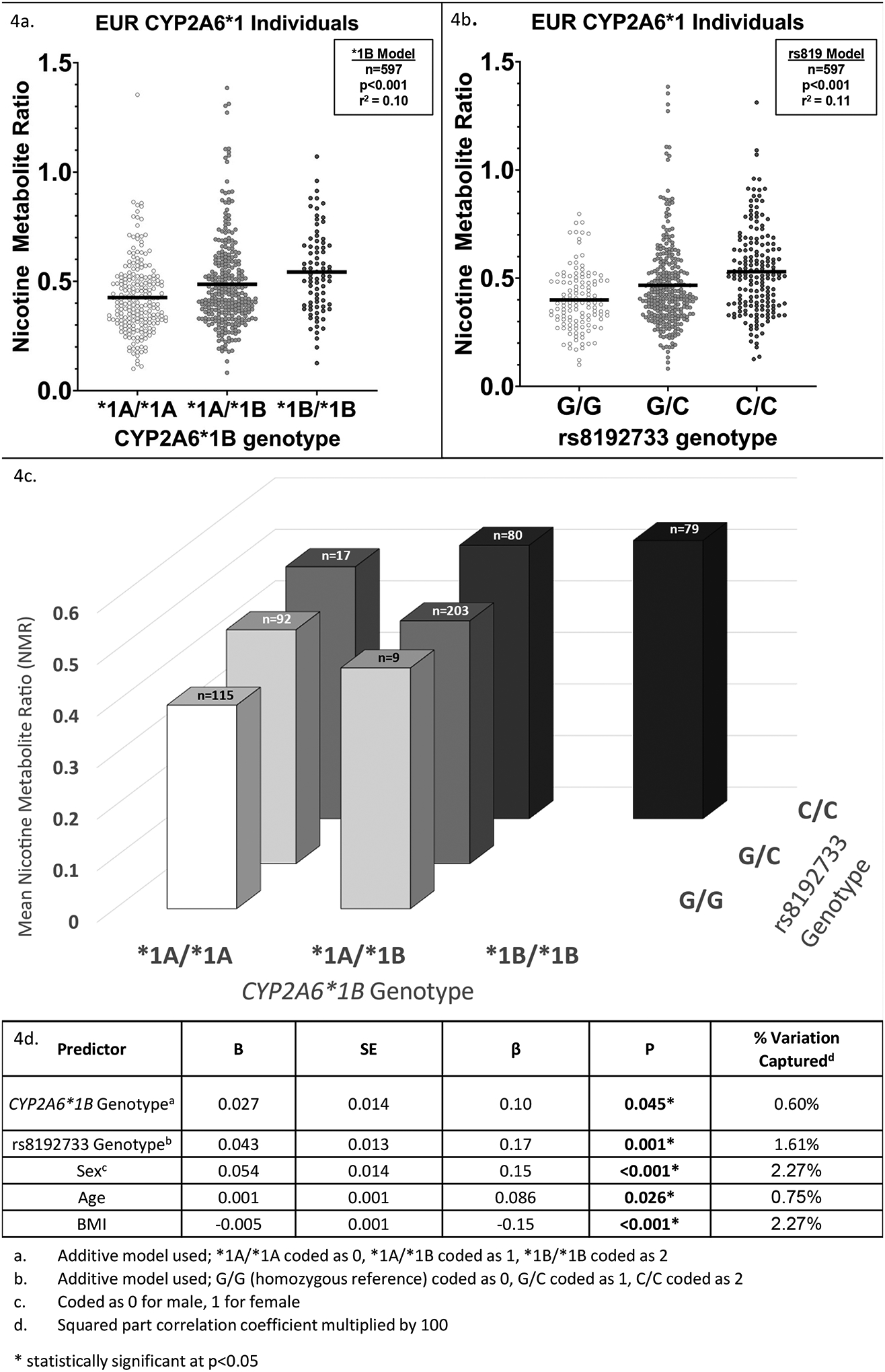

We first examined the influence of CYP2A6*1 (*1A/*1A, *1A/*1B, and *1B/*1B) and rs8192733 genotype (G/G, C/G, and C/C) on logNMR in separate models. Individuals with a known star allele or other exonic non-synonymous variant were excluded. In EUR (n=597), mean logNMR was −0.3611 (SD=0.18; range −1.086, 0.1415). CYP2A6*1B was significantly associated with logNMR (beta=0.054, p<0.001, r2=0.043), which remained significant after controlling for BMI, sex, and age (beta=0.057, p<0.001; model r2=0.10) (Figure 5a). In EUR, rs8192733 was also significantly associated with logNMR (beta=0.060, p<0.001, r2=0.057), which remained significant after controlling for covariates BMI, sex, and age (beta=0.060, p<0.001; model r2=0.11) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotypes are significantly associated with logNMR in European-ancestry individuals.

A. Plot showing mean NMR (horizontal black bars) and individual NMR values (points) within CYP2A6*1B diplotype groups in EUR (n=597). Individuals with known CYP2A6 star variants, structural variants, or other non-synonymous variants were excluded. A linear regression model (“*1B Model”) with CYP2A6*1B genotype, coded additively, and known NMR covariates (age, sex, BMI) included in the model found a significant association of CYP2A6*1B genotype with logNMR (p<0.001, r2=0.10). B. Plot showing mean NMR (horizontal black bars) and individual NMR values (points) within rs8192733 diplotype groups in EUR (n=597). Individuals with known CYP2A6 star variants, structural variants, or other non-synonymous variants were excluded. A linear regression model (“rs819 Model”) with rs8192733 genotype, coded additively, and known NMR covariates (age, sex, BMI) included in the model found a significant association of rs8192733 genotype with logNMR (p<0.001, r2=0.11). C. 3-dimensional bar graph of mean NMR by CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotype in EUR (n=597). Columns with n<5 were not shown. D. Summary table of multiple linear regression of CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotype on logNMR in EUR (n=597). Sex, age, and BMI were included as covariates; all were significantly associated with logNMR. Significant main effects of CYP2A6*1B (p=0.045) and rs8192733 (p=0.001) genotypes were found.

We next evaluated the influence of CYP2A6*1 genotype and rs8192733 genotype on logNMR in the same model. In EUR (total model r2=0.061), only the influence of rs8192733 was significant (beta=0.045, p=0.0008, r2 change=0.018); no main effect of CYP2A6*1B was observed (beta=0.023, p=0.10, r2 change=0.0042). After adjusting for BMI, sex, and age, both CYP2A6*1B (beta=0.027, p=0.045, r2 change=0.006) and rs8192733 (beta=0.043, p=0.0011, r2 change=0.016) significantly influenced logNMR (total model r2=0.12). No significant interaction effect was found (p=0.50) (Figure 5c–d).

In a separate analysis, we included all EUR participants (n=930, n=5 individuals excluded due to lack of NMR data) and adjusted for the presence of known star alleles, structural variants, or other non-synonymous variants. Mean logNMR in this group was −0.44 (SD=0.23; range −1.854, 0.1415). Both CYP2A6*1B (beta=0.033, p=0.023, r2 change=0.0042) and rs8192733 (beta=0.051, p=0.0002, r2 change=0.011) genotypes were found to have significant main effects on logNMR (total model r2=0.25). After adjusting for BMI, sex, and age, the influence of both CYP2A6*1B (beta=0.035, p=0.013, r2 change=0.0047) and rs8192733 (beta=0.051, p<0.001, r2 change=0.012) on logNMR remained significant (total model r2=0.29). No significant interaction effect was found (p=0.11; Supplemental Figure 2).

In contrast to EUR, no associations between CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 genotype and logNMR were found within AFR. A combination of smaller sample size, lower frequencies of CYP2A6*1B (EUR MAF=0.30; AFR MAF=0.17) and rs8192733 (EUR MAF=0.43; AFR MAF=0.19), and higher LD vs. EUR likely contributed to a lack of statistical power to detect associations in AFR (Supplemental Figure 3).

Discussion

Overall, we found that modern SNP array, imputation, and sequencing methods are accurate for CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6 exons. SNP array data (i.e. approaches 2–3) was most likely to be discordant with the gold standard A1 amplicon exon sequencing, but all approaches were ≤2.6% discordant with A1 in exons.

Although discordance at specific positions can be quite high, only 15 positions were highly discordant (>10%) with A1. For example, rs5031017 (characterizing CYP2A6*5) was called discordantly using a SNP array (A2) in >33% of AFR individuals. After excluding rs5031017, the AFR A2 SNP array was only 0.4% discordant. Of the 15 highly discordant positions, several are functionally important (including rs5031017). For example, rs1801272 (characterizing CYP2A6*2) decreases CYP2A6 activity, and is included in the EUR wGRS[9].

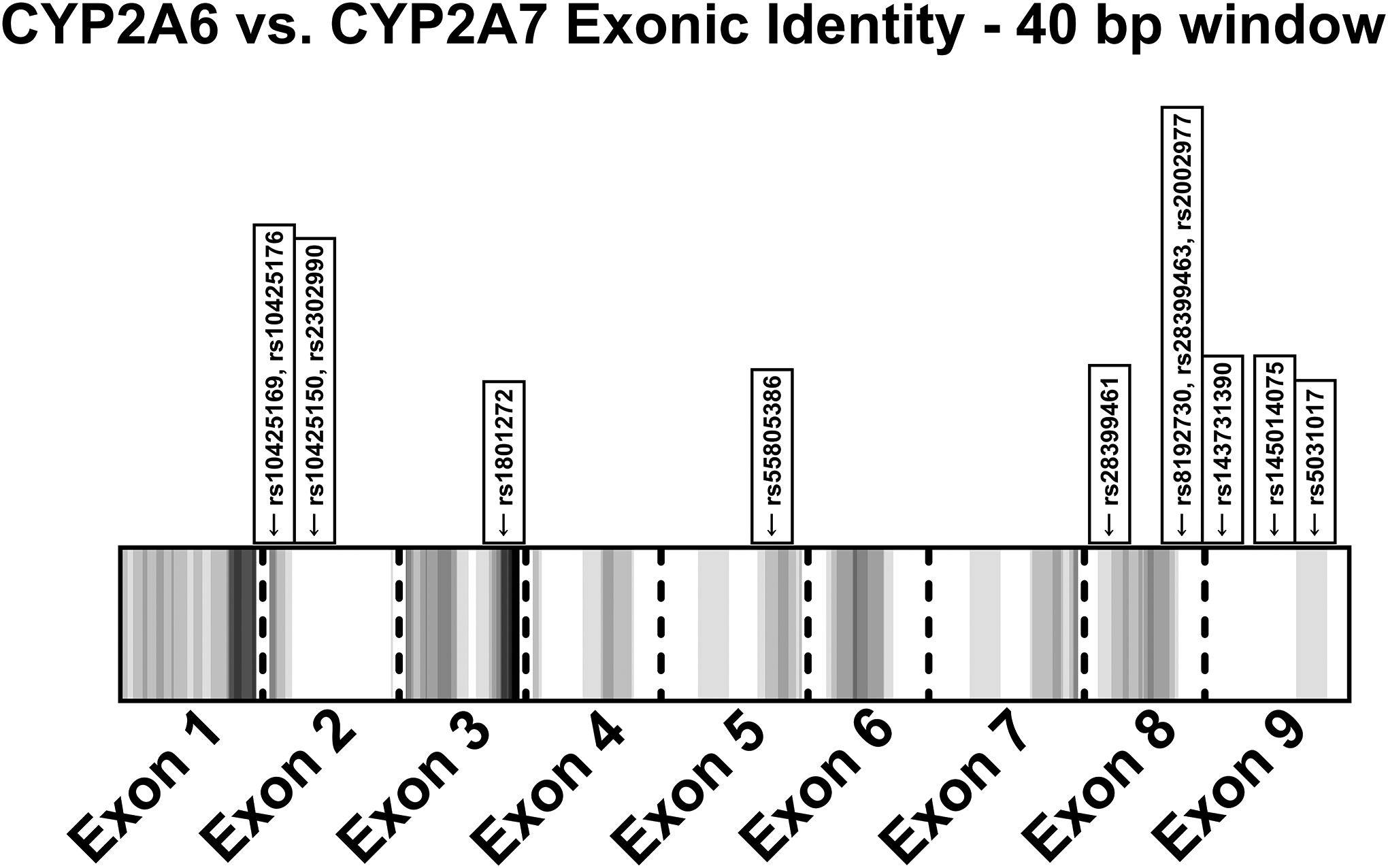

The majority of the 15 highly discordant positions were within areas of high identity between homologous genes (e.g. CYP2A6 and CYP2A7). Spurious read alignments (for sequencing or imputation) or non-gene-specific probes (for SNP arrays) in areas of high identity are likely causes of miscalling (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Heatmap of exonic identity between CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 with highly discordant positions indicated.

The number of non-identical nucleotides within a 40 bp window (+/−20 bp) was calculated for each position. White areas indicate 100% identity within the 40 bp window, while black areas indicate the maximum number of non-identical bases within a 40 bp window (in this analysis, 10 was the maximum); increasing grey intensity indicates greater non-identity. The 13 highly discordant positions in CYP2A6 or CYP2A7 were indicated at their equivalent exonic positions (the other two positions were in CYP2B6).

In our evaluations of positions that were highly discordant between A1 amplicon exon sequencing and A6 targeted capture sequencing, positions with high false positive rates in A6 tended to have higher MAF in online databases vs. our sample, while positions with high false negative rates in A6 tended to have lower MAF in online databases vs. our sample. This suggests that similar read alignment issues may impact the accuracy of online databases at certain positions in CYP2A6 and CYP2B6.

Based on our findings, we’ve developed a set of recommendations for investigating CYP genes in this region:

Sequencing of homologous CYPs (e.g. CYP2A6, CYP2A7 or CYP2A13) should be performed separately using targeted amplicon sequencing or long-read sequencing methods which capture the homologs on a single read. Targeted capture sequencing may capture fragments of homologs, and libraries containing fragments of CYP2A6*1A, CYP2A6*1B, and CYP2A7 3’-UTR sequence may lead to misalignment and incorrect calls. The same is true of CYP2B6 and CYP2B7 exon 5.

Primers for amplicon sequencing of this region must be thoroughly evaluated for potential non-specific gene amplification. As we have shown, online databases may not fully or accurately capture variation in this region. Thus, primers designed according to online sources (BLAST, dbSNP, etc) may be affected by database inaccuracies. Well-established sequencing/genotyping methodologies and primers should be used when possible[29].

Positions in this region where SNP array and sequencing data are likely to be unreliable are identifiable. In particular, genotype data from SNP array or non-gene-specific sequencing in high identity regions should be interpreted with caution. While the positions listed in Table 3 give specific examples of potentially problematic positions, these may differ in other ancestry groups or, for example, in data from a SNP array with higher coverage within CYP exons.

In our investigations of the CYP2A6 3’UTR, we found that the 3’-UTR CYP2A6*1B conversion was associated with higher NMR compared to CYP2A6*1A. CYP2A6*1B is associated with higher CYP2A6 expression and greater mRNA stability in vitro[18]. Previous in vivo investigations in smaller samples have yielded contradictory results, although it is generally accepted that CYP2A6*1B is an increase-of-function variant in EUR[16,31]. Findings in AFR are also equivocal, which may be due to additional loss-of-function variants being in haplotype with the gain-of-function CYP2A6*1B allele[32–34]. rs8192733 was also associated with higher NMR, replicating prior in vitro evidence from a EUR liver bank study[19]. GWAS investigations in a multi-ethnic cohort also found rs8192733 to be associated with both higher NMR and higher lung cancer risk[35]. While both CYP2B6*1B and rs8192733 were associated with higher CYP2A6 activity among EUR in our study, there was a greater relative impact of rs8192733; this may be due to a direct effect on HNRNPA1 binding and mRNA stability due to its localization within the HNRNPA1 binding site[36]. HNRNPA1 specificity is complex and not fully understood, although mRNA sequence at the binding site and secondary structure are factors[37]. While CYP2A6*1B does not directly alter the HNRNPA1 binding site sequence, it may result in altered mRNA secondary structure, leading to altered HNRNPA1 affinity, binding, and mRNA stability.

Our study had several limitations, including the use of masking and re-alignment. If non-specific amplification of CYP2A7 or CYP2B7 occurred, false positive variants could be introduced. Specifically, the two highly discordant CYP2B6 positions may be due to non-specific amplification of CYP2B7 exon 5 aligned to CYP2B6 as a result of CYP2B7 masking. Second, PNAT2 participants were predominantly North American EUR and AFR individuals. Thus, concordance and 3’-UTR variant analyses could not be performed in other populations. Further, 3’-UTR analyses were underpowered in AFR. While trends in impact were similar to EUR, we had 45% and 47% power to detect associations for CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733, respectively; for 80% power, a sample of 489 and 454 individuals, respectively, would be required. Future analyses could use in vitro approaches like luciferase and mRNA stability assays to establish evidence of a causal relationship between rs8192733 and CYP2A6 activity, and bioinformatics approaches such as finemapping to provide in vivo evidence of causality.

In conclusion, we analyzed the concordance of calls from several genotyping and sequencing approaches with calls from a gold standard in CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2A13, and CYP2B6. Genotype calling was highly consistent through most of the exons, but specific positions, while rare, were prone to high rates of discordance. Specifically, positions within areas of high identity between related genes (i.e. CYP2A6 and CYP2A7) made up the majority of highly discordant positions. One variant included in the EUR wGRS, CYP2A6*2, resides at a highly discordant position. Thus, an alternative to SNP array genotyping (e.g. two-step PCR or sequencing) must be used to genotype this variant for effective wGRS use in non-, intermittent-, and former-smokers. We leveraged accurate CYP2A6 3’-UTR sequencing data from our gold standard approach to show associations between the CYP2A6*1B and rs8192733 variants, and CYP2A6 activity in vivo. Overall, our findings provide evidence that variants in this region of chromosome 19, which are not captured reliably by common genotyping and sequencing approaches, may contribute to individual differences in enzyme activity, accounting for some of the missing heritability in CYP2A6 activity.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program (Tyndale, the Canada Research Chair in Pharmacogenomics), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Tyndale, FDN-154294; PJY-159710); National Institutes of Drug Abuse (Tyndale and Lerman, PGRN U01-DA20830) and National Institutes of Cancer (Lerman; NCI R35197461) as well as the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the CAMH Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: RF Tyndale has consulted for Quinn Emanuel and Ethismos Research Inc; all other authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lung Cancer Fact Sheet | American Lung Association. 2019; Available from: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/lung-cancer/resource-library/lung-cancer-fact-sheet.html.

- 2.Tobacco. 2019; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

- 3.Benowitz NL, Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2008. 83(4): p. 531–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajima M, et al. , Role of human cytochrome P4502A6 in C-oxidation of nicotine. Drug Metab Dispos, 1996. 24(11): p. 1212–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dempsey D, et al. , Nicotine metabolite ratio as an index of cytochrome P450 2A6 metabolic activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2004. 76(1): p. 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerman C, et al. , Nicotine metabolite ratio predicts efficacy of transdermal nicotine for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2006. 79(6): p. 600–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benowitz NL, et al. , Nicotine metabolite ratio as a predictor of cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob Res, 2003. 5(5): p. 621–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wassenaar CA, et al. , CYP2A6 reduced activity gene variants confer reduction in lung cancer risk in African American smokers--findings from two independent populations. Carcinogenesis, 2015. 36(1): p. 99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Boraie A, et al. , Evaluation of a weighted genetic risk score for the prediction of biomarkers of CYP2A6 activity. Addict Biol, 2020. 25(1): p. e12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Boraie A, et al. , Transferability of Ancestry-Specific and Cross-Ancestry CYP2A6 Activity Genetic Risk Scores in African and European Populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukami T, et al. , CYP2A7 polymorphic alleles confound the genotyping of CYP2A6*4A allele. Pharmacogenomics J, 2006. 6(6): p. 401–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loukola A, et al. , A Genome-Wide Association Study of a Biomarker of Nicotine Metabolism. PLoS Genet, 2015. 11(9): p. e1005498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swan GE, et al. , Genetic and environmental influences on the ratio of 3’hydroxycotinine to cotinine in plasma and urine. Pharmacogenet Genomics, 2009. 19(5): p. 388–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchwald J, et al. , Genome-wide association meta-analysis of nicotine metabolism and cigarette consumption measures in smokers of European descent. Mol Psychiatry, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerman C, et al. , Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med, 2015. 3(2): p. 131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mwenifumbo JC, et al. , Identification of novel CYP2A6*1B variants: the CYP2A6*1B allele is associated with faster in vivo nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2008. 83(1): p. 115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloom J, et al. , The contribution of common CYP2A6 alleles to variation in nicotine metabolism among European-Americans. Pharmacogenet Genomics, 2011. 21(7): p. 403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Pitarque M, and Ingelman-Sundberg M, 3’-UTR polymorphism in the human CYP2A6 gene affects mRNA stability and enzyme expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2006. 340(2): p. 491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner JA, et al. , Novel CYP2A6 diplotypes identified through next-generation sequencing are associated with in-vitro and in-vivo nicotine metabolism. Pharmacogenet Genomics, 2018. 28(1): p. 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chenoweth MJ, et al. , Genome-wide association study of a nicotine metabolism biomarker in African American smokers: impact of chromosome 19 genetic influences. Addiction, 2018. 113(3): p. 509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purcell S, et al. , PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet, 2007. 81(3): p. 559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson M, et al. , WhatsHap: Weighted Haplotype Assembly for Future-Generation Sequencing Reads. J Comput Biol, 2015. 22(6): p. 498–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimizu M, et al. , Dataset for genotyping validation of cytochrome P450 2A6 whole-gene deletion (CYP2A6*4) by real-time polymerase chain reaction platforms. Data Brief, 2015. 5: p. 642–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaedigk A, et al. , The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: Incorporation of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2018. 103(3): p. 399–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chenoweth MJ, et al. , Known and novel sources of variability in the nicotine metabolite ratio in a large sample of treatment-seeking smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014. 23(9): p. 1773–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phan L, et al. ALFA: Allele Frequency Aggregator. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2020; Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/docs/gsr/alfa/. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auton A, et al. , A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 2015. 526(7571): p. 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karczewski KJ, et al. , The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature, 2020. 581(7809): p. 434–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassenaar CA, Zhou Q, and Tyndale RF, CYP2A6 genotyping methods and strategies using real-time and end point PCR platforms. Pharmacogenomics, 2016. 17(2): p. 147–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machiela MJ and Chanock SJ, LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics, 2015. 31(21): p. 3555–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Koudsi N, et al. , Hepatic CYP2A6 levels and nicotine metabolism: impact of genetic, physiological, environmental, and epigenetic factors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2010. 66(3): p. 239–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwenifumbo JC, et al. , Novel and established CYP2A6 alleles impair in vivo nicotine metabolism in a population of Black African descent. Hum Mutat, 2008. 29(5): p. 679–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho MK, et al. , Association of nicotine metabolite ratio and CYP2A6 genotype with smoking cessation treatment in African-American light smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2009. 85(6): p. 635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasconcelos GM, Struchiner CJ, and Suarez-Kurtz G, CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms and correlation with smoking status in Brazilians. Pharmacogenomics J, 2005. 5(1): p. 42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel YM, et al. , Novel Association of Genetic Markers Affecting CYP2A6 Activity and Lung Cancer Risk. Cancer Res, 2016. 76(19): p. 5768–5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christian K, et al. , Interaction of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 with cytochrome P450 2A6 mRNA: implications for post-transcriptional regulation of the CYP2A6 gene. Mol Pharmacol, 2004. 65(6): p. 1405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain N, et al. , Rules of RNA specificity of hnRNP A1 revealed by global and quantitative analysis of its affinity distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(9): p. 2206–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Boraie A, et al. , Functional Characterization Of Novel Rare CYP2A6 Variants And Potential Implications For Clinical Outcomes. Clin Transl Sci, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadedin SP and Oshlack A, Bazam: a rapid method for read extraction and realignment of high-throughput sequencing data. Genome Biol, 2019. 20(1): p. 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quinlan AR and Hall IM, BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics, 2010. 26(6): p. 841–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poplin R, et al. , Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv, 2018: p. 201178. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chenoweth MJ, et al. , A genome-wide association study of nausea incidence in varenicline-treated cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob Res, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kowalski MH, et al. , Use of >100,000 NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Consortium whole genome sequences improves imputation quality and detection of rare variant associations in admixed African and Hispanic/Latino populations. PLoS Genet, 2019. 15(12): p. e1008500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.