Abstract

Radon is a ubiquitous radioactive gas that decays into a series of solid radioactive decay products. Radon, and its decay products, enter the human body primarily through inhalation and can be delivered to various tissues including the brain through systemic circulation. It can also reach the brain by neuronal pathways via the olfactory system. While ionizing radiation has been suggested as a risk factor of dementia for decades, studies exploring the possible role of radon exposure in the development of Alzheimer’s Diseases (AD) and other dementias are sparse. We systematically reviewed the literature and found several lines of evidence suggesting that radon decay products (RDPs) disproportionally deposit in the brain of AD patients with selective accumulation within the protein fractions. Ecologic study findings also indicate a significant positive correlation between geographic-level radon distribution and AD mortality in the US. Additionally, pathologic studies of radon shed light on the potential pathways of radon decay product induced proinflammation and oxidative stress that may result in the development of dementia. In summary, there are plausible underlying biological mechanisms linking radon exposure to the risk of dementia. Since randomized clinical trials on radon exposure are not feasible, well-designed individual-level epidemiologic studies are urgently needed to elucidate the possible association between radon (i.e., RDPs) exposure and the onset of dementia.

Keywords: radon, RDPs, dementia, cognitive decline, cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

Dementia is abnormal aging of the brain characterized by impaired cognitive function including reasoning, remembering, and thinking (Emmady and Tadi, 2021) that affects approximately 47 million people globally and the prevalence is on an alarmingly upward trend (Arvanitakis et al., 2019). Dementia is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, and imposes a huge economic burden on the society (Wolters and Ikram, 2018). Although the etiology and pathology of dementia is not yet fully understood, ionizing radiation exposure to the brain has been hypothesized to play a role in the development of dementia (Begum et al., 2012; Kempf et al., 2016; Lowe et al., 2009).

Radon (radon-222), a naturally occurring radioactive gas released during the radioactive decay of radium-226, is found in varying concentrations in rocks, soil, and groundwater (Ting, 2010). Radon enters a home, or other buildings, through cracks or other penetrations in the building’s foundation. Radon is also released in homes through the off gassing (e.g., shower, dishwasher, etc.) of radon in groundwater (Field, 2011; Field, 2020). Radon, with a 3.8-day radioactive half-life, decays into a series of solid radioactive decay products (RDPs) that emit alpha particles, beta-particles, and gamma-radiation. RDPs exist in the air either as unattached particles or attached to the surface of aerosol particles (Porstendörfer et al., 2005).

Radon, and RDPs, enter the human body primarily through inhalation and can be delivered to various tissues including the brain through systemic circulation or by neuronal pathways via the olfactory system (Elder et al., 2006; Garcia et al., 2015; Oberdörster et al., 2004). Two of the RDPs, polonium-218 and polonium-214, deliver the majority of radiation dose to the lung (i.e., respiratory epithelium) via alpha particle emission when inhaled. For the average individual in the United States, RDPs exposure is responsible for nearly 70% of our background radiation dose each year (NCRP, 2009). A causal relationship between radon exposure and lung cancer risk has been established for decades. Recently, the impact of radon exposure on other health endpoints has drawn researcher’s attention. Notably, positive associations of radon exposure with overall CVD mortality (Johnson and Duport, 2004; Villeneuve and Morrison, 1997; Zablotska et al., 2018), stroke (Kim et al., 2020), and gestational hypertension (Papatheodorou et al., 2021) have been reported.

Particulate matter (PM) and smoking are well-documented risk factors for dementia (Peters et al., 2019; Peters et al., 2008), and the potential pathways may involve increased risk of hypertension and increased inflammation triggered by oxidative stress and anti-oxidant depletion (Durazzo et al., 2014). RDPs also induce oxidative stress by transmitting or generating reactive oxygen species (Nie et al., 2012). The molecular pathogenesis similarities are not surprising, especially for cigarette smoking, since the solid RDP, polonium-210, contained in and on the tobacco leaves, is one of the most potent carcinogenic constituents of tobacco smoke (Zagà et al., 2011).

Whether RDPs can induce cognitive dysfunction alone or perhaps in a synergistic manner with PM or tobacco smoke is understudied. To this end, the primary objective of this short review is to describe the state of the science in relation to RDPs exposure and dementia. In addition, we highlighted several potential mechanisms linking RDPs exposure to dementia risk.

2. Existing literature

2.1. Literature search

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, and Web of Science for literature published until September 15, 2021. Detailed search strategies are presented in Supplementary Table 1. In brief, we used a combination of key words including “radon,” “RDP,” “cognit*,”, “Alzheimer’s disease,” “AD,” and “dementia”. We imported the search results from all four databases into Covidence to screen for eligibility. After removing 69 duplicates, the total publications entered phase I screening (title and abstract screening) was 427.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were adapted from the PECOS framework (Supplementary Table 2). In brief, studies were included if: 1) radon or RDPs is one of the study exposures; 2) cognitive impairment/decline, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or dementia is one of the study outcomes. There was no restriction on the study design. Based on the eligibility criteria, 408 studies were excluded in phase I due to irrelevancy (e.g., exposure not related to radon or RDPs). Among 19 studies that entered phase II full-text review, five primary studies and one narrative review were eligible. Also, the reference lists of the identified articles were screened for any relevant studies. However, no additional studies were identified, resulting in a total of five studies in the final database.

Two researchers (YZ and LL) independently reviewed the literature during both screening phases and discrepancies were resolved by jointly reviewing the published paper to form a consensus. The detailed literature screening process was summarized in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2. Summary of the existing human studies

To date, research on the association between radon exposure and dementia is limited and preliminary. A review article of radon exposure and neurodegenerative disease pointed to the possible association between radon exposure and AD (Gómez-Anca and Barros-Dios, 2020), although the cited evidence was based only on an early case-control study (Momcilović et al., 1999) and an ecological study (Lehrer et al., 2017) (we described hereunder). Additionally, a summary of the findings from the original studies is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of findings of current literature (original studies only) on radon and dementia

| Study | Study design | Study sample, N | Exposure | Major findings related to dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lehrer, 2017 | Ecological | 50 states and DC | Radon background ionizing radiation | A statistically significant correlation with AD mortality after controlling for some known risk factors such as age, hypertension, and diabetes |

| Momčilović, 2006 | Case report | Post mortem brain of an 86-year-old woman with AD | 210-Po and 210-Bi Radon Daughters | -Radon accumulates higher in the

protein fractions than lipid -Amygdale and hippocampus are the most vulnerable regions of radon radiation |

| Momčilović, 2003 | Case report | |||

| Momčilović, 1999a | Case control | 19 cases (AD) and 8 controls | 210-Po and 210-Bi Radon Daughters | A 10-fold increase of radon daughter radioactivity in the brains of individuals with AD compared to the controls |

| Momčilović, 1999b | Case control |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DC, district of Columbia

In a small case-control study conducted in the laboratory setting, the investigators examined the radon level and its distribution in 29 brain samples from 4 groups of human subjects (those were diagnosed with AD, those were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, smokers and non-smoking controls) (Momcilović et al., 2001; Momcilović et al., 1999). They showed a 10-fold increase of RDPs radioactivity in the cortical gray and subcortical white matter of individuals with AD compared to the non-smoking controls (Momcilović et al., 2001; Momcilović et al., 1999). The RDPs accumulation was predominantly in the protein fractions of cortical grey and subcortical white matters (Momcilović et al., 2001; Momcilović et al., 1999) although a small, yet non-significant increase was also observed in the lipid fraction. The investigators postulated that RDPs may disrupt the protein-built channels in the brain cell membrane of AD patients (Momcilović et al., 2001; Momcilović et al., 1999). Of note, a similar change pattern of radioactivity was observed in the brain samples of smokers (Momcilović et al., 2001; Momcilović et al., 1999).

Later, a case report further explored the distribution of RDPs in the postmortem brain of an 86-year-old woman with AD. It was discovered that RDPs disproportionally accumulated in certain regions such as hippocampus and Nucleus amygdale (Momcilovic and Lykken, 2003; Momčilović et al., 2006), where the process of emotion, memory, and learning are highly involved (Raber et al., 2011).

In addition, Lehrer et al. conducted an ecological study of the association between background radon and AD mortality (per 100,000) in the US (Lehrer et al., 2017) that reported a statistically significant correlation (r=0.467, p=0.001) with the significance persisting after controlling for some known risk factors such as age, hypertension, and diabetes (Lehrer et al., 2017).

In summary, current evidence in human studies was mostly generated from small-scale laboratory research. The capacity of radon to infest the brain was inferred as they observed an increase in RDPs radioactivity in the protein fractions of brains of AD individuals. The credibility of the findings were strengthened by their research practice, i.e., multiple replicates of the samples and two radio-analytical methods. These studies consitently showed that RDPs is an important factor in AD/dementia risk. However, whether RDPs-induced damage is on the etiology pathways of AD/dementia development remains unknown and requires further well-designed large-scale population studies. The ecological study of the association between radon and AD mortality at the state level provided additional evidence to support the hypothesis. Nevertheless, the design of ecological study is only set up for early exploration of the association and limitations such as ecological fallacy preclude researchers from any definitive conclusion on radon exposure and AD/dementia development.

3. Potential mechanisms

The primary route of radon exposure to the lung is through inhalation. After inhalation, radon gas is absorbed into the bloodstream and transported via systemic circulation to the tissues and organs, including the brain, where it reaches a steady state or equilibrium (i.e., radon concentration per milliliter of tissue/radon concentration per milliliter of air) within one hour (Marsh and Bailey, 2013; Nussbaum and Hursh, 1957). The lipid-soluble characteristic of radon gas allows it to pass through the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), but as the gas continues to undergo radioactive decay within the brain, the lipid-insoluble solid radioactive decay products are less mobile resulting in protracted radiation exposure to the brain (Momčilović et al., 2006).

The radioactive decay of radon gas produces charged solid RDPs that can bind to PM or remain unattached (Papastefanou and Bondietti, 1988; Steck et al., 2019). There is evidence that inhaled unattached RDPs and ultrafine particle (UFPs; < 100 nm) attached RDPs can be translocated to other parts of the body, including the brain, through systemic circulation (Genc et al., 2012). However, a more direct route of RDPs central nervous system exposure is deposition of RDPs, unattached or attached to UFPs, on the olfactory mucosa with axonal transport to the olfactory bulb and other areas of the brain (Elder et al., 2006; Garcia et al., 2015; Oberdörster et al., 2004). This route of exposure is supported by research on PM and cognitive function in which ambient particles less than 100 nm were detected in olfactory bulb of the brain (Oberdörster et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2020).

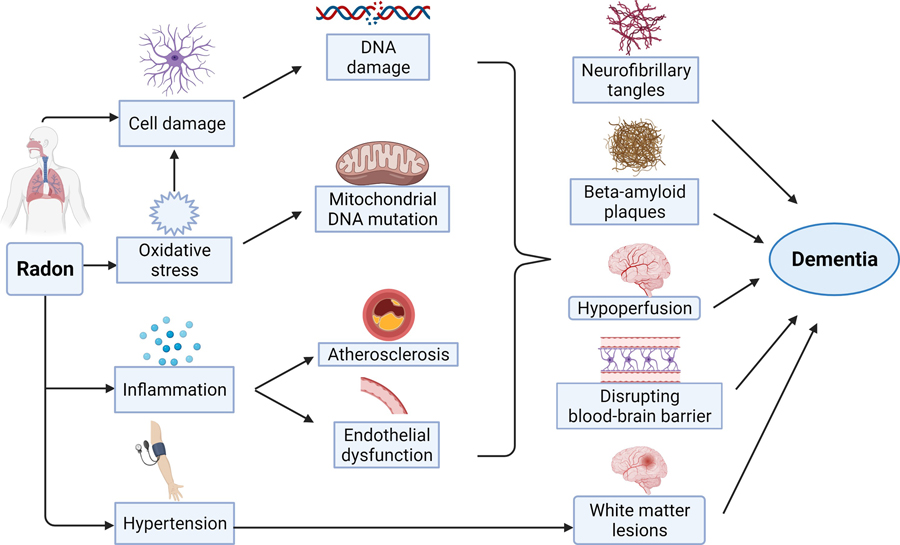

Pathologic studies of radon shed light on the possible pathways that link radon exposure and dementia. We summarized the potential mechanisms in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms linking radon exposure and dementia (created with BioRender.com).

3.1. Vascular mechanisms

AD and vascular dementia are the two leading causes of dementia (Emmady and Tadi, 2021). The signature change of brain structure associated with AD is the abnormal deposition of protein fragments called beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Hardy and Higgins, 1992). There is growing evidence suggesting the role of vascular dysfunction in the onset of these plaques and tangles. Therefore, vascular dementia and AD may not be mutually exclusive.

Several vascular risk factors have been implicated in cognitive impairment. Ionizing radiation, e.g., alpha-emission from radon, can cause various changes to the vascular system such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation, endothelial vascular injury, and fibrous lesion formation, resulting in atherosclerosis (Johnson and Duport, 2004). Additionally, RDPs attached particles have been shown to increase inflammation manifested as elevated level of intercellular adhesion molecule-1,vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and C-reactive protein (Blomberg et al., 2020), leading to vascular endothelial dysfunction. Previous research indicated the role of neurovascular dysfunction in vascular dementia (Shabir et al., 2018).

Also, the central role of cerebral hypoperfusion was proposed (Kelleher and Soiza, 2013). Animal study showed that cerebral hypoperfusion secondary to ischemic stroke may disrupt amyloid clearance and increase neuroinflammation, and consequently, the development of dementia (Back et al., 2017). Epidemiologic evidence also demonstrated that stroke is associated with the development and deterioration of cognitive decline during late adulthood (Kaffashian et al., 2013; Li et al., 2011).

In addition, exposure to RDPs have been suggested to associate with increased blood pressure independent of PM (Nyhan Marguerite et al.). Higher residential radon exposure was also linked to increased risk of hypertension in pregnant women (Papatheodorou et al., 2021). Research has pointed to the link between hypertension and dementia (de la Torre, 2012; Pires et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2019). Elevated blood pressure may increase the risk for dementia by inducing cerebral small vessel disease and white-matter lesions, disrupting BBB, and production of free radicals (Berry et al., 2001; Skoog et al., 1996).

Moreover, prolonged exposure, e.g., 18–30 years to the radiation may lead to various downstream circulatory diseases including ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease (Johnson and Duport, 2004; Kim et al., 2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested the potential association between low-dose ionizing radiation and circulatory disease mortality in the occupational population (Little et al., 2012). Since cardiovascular diseases are highly related to dementia (Newman et al., 2005), it is presumable that radon may play a role in the development of dementia by modification of vascular function.

3.2. Cellular damage

Human brain cells can be classified into neurons and glial cells. While neurons are key cells for signal transduction, glial cells are proliferating cells, playing an important role in defense and regeneration of CNS (Rodríguez-Arellano et al., 2016). They also supply neurons with essential proteins for memory formation (Momcilović et al., 1999). Astrocyte is one special type of glial cells and is vital in the control of BBB. Research showed that glial cells, e.g., astrocytes, are more radiation-sensitive than neurons (Kudo et al., 2014). The energy produced by ionizing radiation may directly cause DNA damage in the cells or indirectly via the production of reactive oxygen species. Glial cells have been shown to undergo mitotic cell death subsequent to radiation (Kudo et al., 2014), potentially due to DNA damage. Delayed development of astrocytes was also observed due to low-dose irradiation. Additionally, animal models have demonstrated that stress, such as ionizing radiation, may induce astrocyte senescence via the epigenetic pathways (Turnquist et al., 2019).

Damaged glial cells, especially astrocytes, may contribute to the development of dementia/AD (Rodríguez-Arellano et al., 2016). Abnormal astrocytes may secrete variant of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) that can foster the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (Momcilović et al., 1999). Additionally, although cellular senescence is considered a normal process of aging, astrocytes senescence has been postulated in the pathologic process of AD (Han et al., 2020). In vitro studies showed that when astrocytes undergo senescence, they lost the normal physiological function, which may contribute to the amyloid deposition related to AD (Han et al., 2020).

3.3. Mitochondria dysfunction

Mitochondria are key player in the process of cell apoptosis (Li et al., 2012) and brain is the organ most reliant on mitochondrial energy balance for normal activity (Coskun et al., 2012). In vitro studies demonstrated that radon exposure could induce mitochondrial dysfunction and malignant cell transformation (Li et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2019). Oxidative stress induced by radon exposure could also contribute to mitochondria dysfunction and mitochondria DNA mutations (Stuart and Brown, 2006).

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease including AD. Specifically, mitochondria DNA copy number (mtDNAcn), a novel biomarker for cognitive decline, has been shown to be lower in the postmortem brains of cognitive impaired patients compared to the control individuals (Coskun et al., 2004; Coskun et al., 2010; Silzer et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2017). However, future human studies that directly linked radon exposure to mitochondrial function such as mtDNAcn are warranted.

4. Implications for future studies

Currently, research of the association between protracted radon exposure and cognitive impairment is still at the early stage. Although laboratory studies have provided reliable results suggesting the accumulation of RDPs radioactivity in the brains of individuals with AD, few epidemiologic studies have been carried out to confirm the potential association. Research that examined county-level radon in relation to some other health outcomes (e.g., cerebrovascular disease) has shed light on the investigation of radon as a risk factor for dementia.

However, the information of within-county variations is missing when utilizing the county-level radon data. While concerns about the health impact of radon exposure are increased, measuring radon exposure at the individual household level has become crucial for any definitive conclusion. The easy access of indoor radon test procedure makes large epidemiological study feasible nowadays. Also, some important ancillary factors such as tobacco use, air pollution as well as climate factors (e.g., humidity and temperature) should be considered during data collection and analysis. For example, research suggests that the physiological pathways of radon may be overlapped with those of toxins from cigarette smoke or air polluting particles. Thus, possible synergistic effects of these environmental factors merit researcher’s attention in addition to controlling for other factors when studying the health impact of radon exposure. Additionally, future studies should strive for consistent outcome definition among individuals, as dementia could be a result of multiple mechanisms of cognitive decline. In order to reduce bias of misclassification, physician diagnosis or validated questionnaires should be implemented in data collection.

5. Conclusions

In this review, we performed a systematic search to identify all available literature related to radon (including RDPs) and cognitive impairment/dementia. However, the direct evidence linking radon/RDPs exposure to dementia is scarce. The included studies were case report, small-scale case-control study, and ecological study. Therefore, the existing studies of dementia in relation to radon/RDPs exposure is not sufficient yet, though there are plausible underlying biological mechanisms. Because of the large population at risk from protracted radon exposure and randomized clinical trial is not practically feasible, rigorous population-based studies are urgently needed to better understand the potential causal association between protracted radon (i.e., RDPs) exposure and dementia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

YZ: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing - original draft

LL: Methodology; Visualization; Writing – review & editing

CC: Writing – review & editing

RWF: Investigation; Writing – review & editing

MD: Writing – review & editing

KK: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing – review & editing

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01NS122449 and RF1AG056111, 2021]

Abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- BBB

Blood-brain-barrier

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- PM

Particulate matter

- RDP

Radon decay product

- UFP

Ultrafine particle

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA, 2019. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA. 322, 1589–1599. 10.1001/jama.2019.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back DB, Kwon KJ, Choi D-H, Shin CY, Lee J, Han S-H, Kim HY, 2017. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induces post-stroke dementia following acute ischemic stroke in rats. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 14, 216. 10.1186/s12974-017-0992-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum N, Wang B, Mori M, Vares G, 2012. Does ionizing radiation influence Alzheimer’s disease risk? J Radiat Res. 53, 815–22. 10.1093/jrr/rrs036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry C, Brosnan MJ, Fennell J, Hamilton CA, Dominiczak AF, 2001. Oxidative stress and vascular damage in hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 10, 247–55. 10.1097/00041552-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg AJ, Nyhan MM, Bind M-A, Vokonas P, Coull BA, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, 2020. The Role of Ambient Particle Radioactivity in Inflammation and Endothelial Function in an Elderly Cohort. Epidemiology. 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun P, Wyrembak J, Schriner SE, Chen HW, Marciniack C, Laferla F, Wallace DC, 2012. A mitochondrial etiology of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1820, 553–64. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC, 2004. Alzheimer’s brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 10726–31. 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, Melkonian G, Doran E, Lott IT, Head E, Cotman CW, Wallace DC, 2010. Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 2, S293–310. 10.3233/jad-2010-100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre JC, 2012. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovascular psychiatry and neurology. 2012, 367516–367516. 10.1155/2012/367516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Mattsson N, Weiner MW, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I, 2014. Smoking and increased Alzheimer’s disease risk: a review of potential mechanisms. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 10, S122–S145. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder A, Gelein R, Silva V, Feikert T, Opanashuk L, Carter J, Potter R, Maynard A, Ito Y, Finkelstein J, Oberdörster G, 2006. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine manganese oxide particles to the central nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 114, 1172–8. 10.1289/ehp.9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmady P, Tadi P, Dementia. Vol. 2021. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Field RW, 2011. Radon: An Overview of Health Effects. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. 4, 745–753. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52272-6.00095-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field RW, Reducing the Risk from Radon: Information and Interventions - A Guide for Health Care Providers. Council of Radiation Control Program Directors, Inc., Frankfort, KY, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia GJ, Schroeter JD, Kimbell JS, 2015. Olfactory deposition of inhaled nanoparticles in humans. Inhal Toxicol. 27, 394–403. 10.3109/08958378.2015.1066904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc S, Zadeoglulari Z, Fuss SH, Genc K, 2012. The adverse effects of air pollution on the nervous system. J Toxicol. 2012, 782462. 10.1155/2012/782462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Anca S, Barros-Dios JM, 2020. Radon Exposure and Neurodegenerative Disease. International journal of environmental research and public health. 17, 7439. 10.3390/ijerph17207439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Zhang T, Liu H, Mi Y, Gou X, 2020. Astrocyte Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 12. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA, 1992. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 256, 184–5. 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JR, Duport P, 2004. Cardiovascular Mortality Caused by Exposure to Radon. IRPA, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Elbaz A, Shipley MJ, Sabia S, Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A, 2013. Predicting cognitive decline: a dementia risk score vs. the Framingham vascular risk scores. Neurology. 80, 1300–1306. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, Soiza RL, 2013. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in the development of Alzheimer’s disease: Is Alzheimer’s a vascular disorder? American journal of cardiovascular disease. 3, 197–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf SJ, Janik D, Barjaktarovic Z, Braga-Tanaka I III, Tanaka S, Neff F, Saran A, Larsen MR, Tapio S, 2016. Chronic low-dose-rate ionising radiation affects the hippocampal phosphoproteome in the ApoE −/− Alzheimer’s mouse model. Oncotarget. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Park JM, Kim H, 2020. The prevalence of stroke according to indoor radon concentration in South Koreans: Nationwide cross section study. Medicine (Baltimore). 99, e18859. 10.1097/md.0000000000018859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S, Suzuki Y, Noda S-E, Mizui T, Shirai K, Okamoto M, Kaminuma T, Yoshida Y, Shirao T, Nakano T, 2014. Comparison of the radiosensitivities of neurons and glial cells derived from the same rat brain. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 8, 754–758. 10.3892/etm.2014.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH, Rosenzweig KE, 2017. Association of Radon Background and Total Background Ionizing Radiation with Alzheimer’s Disease Deaths in U.S. States. J Alzheimers Dis. 59, 737–741. 10.3233/jad-170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li BY, Sun J, Wei H, Cheng YZ, Xue L, Cheng ZH, Wan JM, Wang AQ, Hei TK, Tong J, 2012. Radon-induced reduced apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells with knockdown of mitochondria DNA. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 75, 1111–9. 10.1080/15287394.2012.699841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang YJ, Zhang M, Xu ZQ, Gao CY, Fang CQ, Yan JC, Zhou HD, 2011. Vascular risk factors promote conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 76, 1485–91. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e7a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little MP, Azizova TV, Bazyka D, Bouffler SD, Cardis E, Chekin S, Chumak VV, Cucinotta FA, de Vathaire F, Hall P, Harrison JD, Hildebrandt G, Ivanov V, Kashcheev VV, Klymenko SV, Kreuzer M, Laurent O, Ozasa K, Schneider T, Tapio S, Taylor AM, Tzoulaki I, Vandoolaeghe WL, Wakeford R, Zablotska LB, Zhang W, Lipshultz SE, 2012. Systematic review and meta-analysis of circulatory disease from exposure to low-level ionizing radiation and estimates of potential population mortality risks. Environ Health Perspect. 120, 1503–11. 10.1289/ehp.1204982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe XR, Bhattacharya S, Marchetti F, Wyrobek AJ, 2009. Early brain response to low-dose radiation exposure involves molecular networks and pathways associated with cognitive functions, advanced aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Radiat Res. 171, 53–65. 10.1667/rr1389.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JW, Bailey MR, 2013. A review of lung-to-blood absorption rates for radon progeny. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 157, 499–514. 10.1093/rpd/nct179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilović B, Alkhatib HA, Duerre JA, Cooley M, Long WM, Harris TR, Lykken GI, 2001. Environmental lead-210 and bismuth-210 accrue selectively in the brain proteins in Alzheimer disease and brain lipids in Parkinson disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 15, 106–15. 10.1097/00002093-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilović B, Alkhatib HA, Duerre JA, Cooley MA, Long WM, Harris RT, Lykken GI, 1999. Environmental radon daughters reveal pathognomonic changes in the brain proteins and lipids in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and cigarette smokers. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 50, 347–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilovic B, Lykken GI, Distribution of 210-Po and 210-Bi Radon Daughters in the Brain Proteins of a Subject who Suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease. Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium of the Croatian Radiation Protection Association, Croatia, 2003, pp. 407. [Google Scholar]

- Momčilović B, Lykken GI, Cooley M, 2006. Natural distribution of environmental radon daughters in the different brain areas of an Alzheimer Disease victim. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 1, 11. 10.1186/1750-1326-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Jackson S, Lyketsos C, Jagust W, Ives D, Dekosky ST, Kuller LH, 2005. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease incidence in relationship to cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 53, 1101–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Ionizing radiation exposure of the population of the United States. . Report No. 160. NCRP, Bethesda, MD, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nie JH, Chen ZH, Liu X, Wu YW, Li JX, Cao Y, Hei TK, Tong J, 2012. Oxidative damage in various tissues of rats exposed to radon. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 75, 694–9. 10.1080/15287394.2012.690086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum E, Hursh JB, 1957. Radon solubility in rat tissues. Science. 125, 552–3. 10.1126/science.125.3247.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan Marguerite M, Coull Brent A, Blomberg Annelise J, Vieira Carol LZ, Garshick E, Aba A, Vokonas P, Gold Diane R, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, Associations Between Ambient Particle Radioactivity and Blood Pressure: The NAS (Normative Aging Study). Journal of the American Heart Association. 7, e008245. 10.1161/JAHA.117.008245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdörster G, Sharp Z, Atudorei V, Elder A, Gelein R, Kreyling W, Cox C, 2004. Translocation of inhaled ultrafine particles to the brain. Inhal Toxicol. 16, 437–45. 10.1080/08958370490439597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastefanou C, Bondietti EA, 1988. Radon daughter aerosols in ambient air. Science of The Total Environment. 70, 69–82. 10.1016/0048-9697(88)90252-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou S, Yao W, Vieira CLZ, Li L, Wylie BJ, Schwartz J, Koutrakis P, 2021. Residential radon exposure and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Massachusetts, USA: A cohort study. Environ Int. 146, 106285. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, Booth A, Mudway I, Anstey KJ, 2019. Air Pollution and Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 70, S145–s163. 10.3233/jad-180631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C, 2008. Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review. BMC geriatrics. 8, 36–36. 10.1186/1471-2318-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM, 2013. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 304, H1598–614. 10.1152/ajpheart.00490.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porstendörfer J, Pagelkopf P, Gründel M, 2005. Fraction of the positive 218Po and 214Pb clusters in indoor air. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 113, 342–51. 10.1093/rpd/nch465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, Villasana L, Rosenberg J, Zou Y, Huang TT, Fike JR, 2011. Irradiation enhances hippocampus-dependent cognition in mice deficient in extracellular superoxide dismutase. Hippocampus. 21, 72–80. 10.1002/hipo.20724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Arellano JJ, Parpura V, Zorec R, Verkhratsky A, 2016. Astrocytes in physiological aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 323, 170–182. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos N. V. d., Vieira CLZ, Saldiva PHN, Paci Mazzilli B, Saiki M, Saueia CH, De André CDS, Justo LT, Nisti MB, Koutrakis P, 2020. Levels of Polonium-210 in brain and pulmonary tissues: Preliminary study in autopsies conducted in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Scientific Reports. 10, 180. 10.1038/s41598-019-56973-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabir O, Berwick J, Francis SE, 2018. Neurovascular dysfunction in vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s and atherosclerosis. BMC Neurosci. 19, 62. 10.1186/s12868-018-0465-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silzer T, Barber R, Sun J, Pathak G, Johnson L, O’Bryant S, Phillips N, 2019. Circulating mitochondrial DNA: New indices of type 2 diabetes-related cognitive impairment in Mexican Americans. PLoS One. 14, e0213527. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog I, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, Palmertz B, Andreasson LA, Nilsson L, Persson G, Odén A, Svanborg A, 1996. 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet. 347, 1141–5. 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck DJ, Sun K, William Field R, 2019. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Indoor Airborne Radon Decay Product Dose Rate and Surface-Deposited Radon Decay Products in Homes. Health Phys. 116, 582–589. 10.1097/hp.0000000000000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart JA, Brown MF, 2006. Mitochondrial DNA maintenance and bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1757, 79–89. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting DSK, WHO handbook on indoor radon: a public health perspective. Taylor & Francis, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turnquist C, Beck JA, Horikawa I, Obiorah IE, Von Muhlinen N, Vojtesek B, Lane DP, Grunseich C, Chahine JJ, Ames HM, Smart DD, Harris BT, Harris CC, 2019. Radiation-induced astrocyte senescence is rescued by Δ133p53. Neuro-oncology. 21, 474–485. 10.1093/neuonc/noz001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve PJ, Morrison HI, 1997. Coronary heart disease mortality among Newfoundland fluorspar miners. Scand J Work Environ Health. 23, 221–6. 10.5271/sjweh.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KA, Sharrett AR, Wu A, Schneider ALC, Albert M, Lutsey PL, Bandeen-Roche K, Coresh J, Gross AL, Windham BG, Knopman DS, Power MC, Rawlings AM, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF, 2019. Association of Midlife to Late-Life Blood Pressure Patterns With Incident Dementia. JAMA. 322, 535–545. 10.1001/jama.2019.10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Keogh MJ, Wilson I, Coxhead J, Ryan S, Rollinson S, Griffin H, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Santibanez-Koref M, Talbot K, Turner MR, McKenzie CA, Troakes C, Attems J, Smith C, Al Sarraj S, Morris CM, Ansorge O, Pickering-Brown S, Ironside JW, Chinnery PF, 2017. Mitochondrial DNA point mutations and relative copy number in 1363 disease and control human brains. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 5, 13. 10.1186/s40478-016-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters FJ, Ikram MA, 2018. Epidemiology of Dementia: The Burden on Society, the Challenges for Research. Methods Mol Biol. 1750, 3–14. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7704-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Fang L, Chen B, Zhang H, Wu Q, Zhang H, Wang A, Tong J, Tao S, Tian H, 2019. Radon induced mitochondrial dysfunction in human bronchial epithelial cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition with long-term exposure. Toxicol Res (Camb). 8, 90–100. 10.1039/c8tx00181b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotska LB, Fenske N, Schnelzer M, Zhivin S, Laurier D, Kreuzer M, 2018. Analysis of mortality in a pooled cohort of Canadian and German uranium processing workers with no mining experience. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 91, 91–103. 10.1007/s00420-017-1260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagà V, Lygidakis C, Chaouachi K, Gattavecchia E, 2011. Polonium and Lung Cancer. Journal of Oncology. 2011, 860103. 10.1155/2011/860103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.