Abstract

The efficacy of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma (CCP) as a treatment for hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 remains somewhat controversial; however, many studies have not evaluated CCP documented to have high neutralizing antibody titer by a highly accurate assay. To evaluate the correlation of the administration of CCP with titer determined by a live viral neutralization assay with 7‐ and 28‐day death rates during hospitalization, a total of 23 118 patients receiving a single unit of CCP were stratified into two groups: those receiving high titer CCP (>250 50% inhibitory dilution, ID50; n = 13 636) or low titer CCP (≤250 ID50; n = 9482). Multivariable Cox regression was performed to assess risk factors. Non‐intubated patients who were transfused with high titer CCP showed 1.1% and 1.7% absolute reductions in overall 7‐ and 28‐day death rates, respectively, compared to those non‐intubated patients receiving low titer CCP. No benefit of CCP was observed in intubated patients. The relative benefit of high titer CCP was confirmed in multivariable Cox regression. Administration of CCP with high titer antibody content determined by live viral neutralization assay to non‐intubated patients is associated with modest clinical efficacy. Although shown to be only of modest clinical benefit, CCP may play a role in the future should viral variants develop that are not neutralized by other available therapeutics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Clinical manifestations of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19), caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection, range from mild and self‐limited to life‐threatening respiratory, systemic illness, and death. 1 Potential therapeutics have been proposed or investigated, including antivirals, corticosteroids, immune therapies, antibiotics, and anticoagulation. 2 One of the earliest proposed therapies was CP collected from recovered patients for use as a passive immune therapy, 3 , 4 whereby antibodies can be transferred from recovered patients to others to protect from illness or treat active disease. Historically, such approaches appear most effective in the earliest phases of illness, or as prophylaxis. 5 Although CP is frequently one of the earliest available therapies following the spread of a newly emergent infectious disease, its efficacy has only rarely been examined in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). 6 , 7 While trials in some viral illnesses, such as Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever, reported positive results, 8 others, including some trials in severe type A influenza, have not. 9 Historical data has suggested possible benefit in the case of other respiratory virus infections, including coronaviruses such as SARS‐CoV‐1 and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, but the interpretation of such studies is limited by their non‐randomized designs. 10 , 11 Factors complicating the rigorous study of CP include the following: the urgent nature of the outbreaks in which CP use is usually considered (which can limit the ability to mobilize resources for clinical trials); the heterogeneous nature of the product; its decentralized manufacture; limitations in the ability to quantify the biologic activity; and eventual availability of alternative therapies, such as antivirals, purified preparations of immune globulins, or monoclonal antibodies, that may not carry some of the risks and practical challenges associated with transfusion of blood products such as plasma.

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, initial preclinical animal models suggested potential benefit with passive immune therapies, 12 , 13 , 14 and non‐human primate models found passive transfer of immunoglobulins could protect against infection, and provide therapeutic efficacy following viral challenge, in a dose‐dependent manner. 15 , 16 Additionally, early in the pandemic, case series reported positive outcomes in patients treated with CP from donors recovered from COVID‐19 (COVID‐19 Convalescent Plasma, CCP). 17 , 18 , 19 Considering the available data, the limited treatment options, and the historical precedent, FDA made CCP available for use starting in April 2020. This was initially under individual patient emergency Investigational New Drug applications (eINDs) and subsequently also under a national expanded access protocol (EAP) sponsored by the Mayo Clinic that ultimately transfused more than 90 000 patients by August 2020 when enrollment was closed. A key aspect of the EAP was providing access to CCP at community hospitals. Concurrently, several RCTs moved forward under IND, including various trial designs and study populations, such as prophylaxis, early outpatient use, and hospitalized patients with severe disease. 20 , 21

Initial reports from the Mayo‐sponsored EAP demonstrated an acceptable safety profile; adverse event rates were consistent with transfusion of non‐immune plasma. 22 Several observational or non‐randomized studies found positive outcomes compared to matched controls. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 However, early RCT data were largely limited to two trials that were stopped early. 27 , 28 These trials failed to demonstrate benefit in their primary endpoints at the time of stopping and were underpowered to detect clinically meaningful benefit. Considering limitations in available data as of August 2020, as the scale of the pandemic and CCP use under the EAP continued to grow, preliminary data on the potential efficacy of CCP were needed to guide regulatory decision making.

This situation provided the impetus to use real world evidence (RWE) generated from the large number of individuals enrolled in the EAP to assess the efficacy of CCP using SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody titers determined by a highly accurate live viral neutralization assay. Quantitative serologic and neutralizing antibody tests of CCP donations were unavailable at the time the EAP was established and would remain limited until late 2020. 29 Therefore, for EAP transfusions, both serologic and neutralizing antibody titers were unknown at the time of CCP infusion. The random nature of the CCP titers administered was used to assess the clinical efficacy of CCP by comparing outcomes in low versus high titer and early versus late CCP infusions. We hypothesized that a dose–response relationship between live viral neutralizing antibody titers and clinical outcomes could provide insight into potential efficacy of CCP.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The EAP was a national study of hospitalized adults with COVID‐19 sponsored by the Mayo Clinic (NCT04338360). Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with applicable regulations and with oversight from the sponsor's Institutional Review Board. The patients and institutions participating in the EAP for CCP have been previously described. 22 Greater than 99.9% of transfusions were performed between April 4th to August 31st, 2020. Patients were categorized by HHS regions based on the transfusing hospital location. The analysis was limited to patients who had a known intubation status at time of transfusion (43 “unknown” cases excluded) and who had received only one unit of CCP with a reported live viral neutralization titer, to reduce confounding due to multiple exposures at various doses from different donors. Subjects enrolled in the EAP were followed during their hospital stay and not after discharge. Considering this limitation, the primary analyses assumed survival after discharge. As a more conservative approach, the 7‐ and 28‐day death rates for patients remaining in the hospital (for whom survival could be directly observed) were also assessed. This approach required that a patient had accumulated at least 7 or 28 days of follow‐up time or have a recorded death to calculate the 7‐ and 28‐day death rates, respectively. Due to this follow‐up time constraint to assess survival, 7‐day death rate denominators were larger than 28‐day death rate denominators, as patients would be discharged in the intervening time period. A detailed description of patient characteristics and attrition observed from the 7‐ and 28‐day analyses is included in Table 1. 30

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| All Patients (%) | Hospitalized at least 7 days (%) | Hospitalized at least 28 days (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40 and Under | 2379 (10.3) | 1054 (6.9) | 378 (4.7) |

| 40–60 | 8133 (35.2) | 4912 (32.1) | 2111 (26.4) | |

| 61–80 | 10 054 (43.5) | 7382 (48.3) | 4227 (52.9) | |

| 81+ | 2552 (11.0) | 1945 (12.7) | 1269 (15.9) | |

| Gender | Male | 13 529 (58.5) | 9222 (60.3) | 4850 (60.7) |

| Female | 9514 (41.2) | 6032 (39.4) | 3114 (39.0) | |

| Other | 75 (0.3) | 39 (0.2) | 21 (0.3) | |

| Race | White | 11 909 (51.5) | 7793 (51.0) | 4063 (51.0) |

| Asian | 764 (3.3) | 533 (3.5) | 288 (3.6) | |

| Black, African American | 4527 (19.6) | 2969 (19.4) | 1560 (19.5) | |

| Other/Unknown | 5918 (25.6) | 3998 (26.1) | 2074 (26.0) | |

| Broad titer (ID50) | Low (<250) | 9482 (41.0) | 6298 (41.2) | 3319 (41.6) |

| High (≥250) | 13 636 (59.0) | 8995 (58.8) | 4666 (58.4) | |

| HHS | 1 (ME, MA, CT, RI, NH, VT) | 245 (1.1) | 180 (1.2) | 100 (1.3) |

| Region | 2 (NY, NJ, PR, USVI) | 827 (3.6) | 657 (4.3) | 438 (5.5) |

| 3 (PA, MD, VA, WV, DE, DC) | 1691 (7.3) | 1119 (7.3) | 619 (7.8) | |

| 4 (KY, TN, NC, SC, MI, AL, GA, FL) | 7888 (34.1) | 5115 (33.4) | 2652 (33.2) | |

| 5 (MN, WI, MI, IL, IN, OH) | 2329 (10.1) | 1641 (10.7) | 854 (10.7) | |

| 6 (NM, TX, OK, AR, LA) | 4353 (18.8) | 2726 (17.8) | 1354 (17.0) | |

| 7 (IA, MO, KS, NE) | 1043 (4.5) | 640 (4.2) | 270 (3.4) | |

| 8 (MT, ND, SD, WY, CO, UT) | 555 (2.4) | 314 (2.1) | 139 (1.7) | |

| 9 (CA, NV, AZ, HI) | 3897 (16.9) | 2718 (17.8) | 1472 (18.4) | |

| 10 (WA, OR, ID, AK) | 290 (1.3) | 183 (1.2) | 87 (1.1) | |

| Total | 23 118 | 15 293 | 7985 |

Note: Descriptive statistics of the patient age, gender, reported race, CCP titer, and HHS region as recorded upon hospitalization. 7‐day and 28‐day columns represent the number of patients hospitalized at least 7 or 28 days, respectively. Numbers in parentheses represent the percent of patients in the respective category and may not add to 100% due to rounding.

2.2. Donor qualification and CCP antibody titers

CCP was collected from eligible blood donors in accordance with FDA guidance effective at the time (Investigational COVID‐19 Convalescent Plasma, April 2020). However, at the time of the study transfusions, there were no validated assays for quantification of neutralizing anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies for the purpose of qualifying the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody titer of CCP donations. For a proportion of the plasma donations used under the EAP, retained specimens were available to retrospectively measure neutralizing antibody titers. Assays used included a robotic live virus neutralization assay performed under BSL‐3 laboratory conditions by the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA) using native SARS‐CoV‐2 virus (50% inhibitory dilution; ID50), an assay of IgG against SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein (Ortho VITROS IgG); and a neutralization assay using a pseudo‐typed virus bearing SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein (Mayo Clinic). While initial analyses suggested these assays were all positively correlated, the Broad Institute assay was chosen as the reference method for this analysis due to its throughput, reproducibility, and expected accuracy when compared to plaque‐reduction neutralization titer methodology.

2.3. SARS‐CoV‐2 live virus neutralization assay

Live‐virus SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody neutralization was performed at Broad Institute on a high throughput platform (BROAD PRNT). Vero E6‐TMPRSS2 were seeded at 10000 cells per well the day prior to infection in a CellCarrier‐384 ultra‐microplate (Perkin Elmer). Patient plasma samples were tested at a starting dilution of 1:40 and were serially diluted 2‐fold up to 1:5120. Serially diluted patient plasma was mixed separately with diluted SARS‐CoV‐2 live virus (D614) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 hour; after which the plasma‐virus complexes were added to the Vero E6‐TMPRSS2 cells and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Cells were then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature, washed, and incubated with diluted anti‐SARS‐CoV/SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleoprotein mouse antibody (Sino Biological) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. They were subsequently incubated with Alexa488‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) for 45 minutes at room temperature, followed by nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fluorescence imaging was performed using the Opera Phenix™ High Content Screening System (Perkin Elmer). Half‐maximal inhibitory dilutions (ID50) were determined using a four‐parameter, nonlinear curve fitting algorithm. For samples that were non‐neutralizing (fitted curve did not show >10% inhibition at any concentration) or highly neutralizing (fitted curve showed >90% inhibition at all concentrations) tested, the resulting ID50 values were capped at 20 and 10 240, respectively.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Due to the lack of a control cohort in this observational study, the analysis relied on CCP of varying antibody titers being randomly distributed to patients because the titer of the administered CCP was not known a priori. Patients were assigned into 2 prespecified treatment groups, depending on whether they received “high” (≥250) or “low” (<250) titer CCP based on the neutralization activity, reported as an ID50. The 7‐ and 28‐day death rates were calculated by dividing the total number of recorded deaths by day 7 and day 28 with the number of individuals who either were alive at the time of discharge (or at the specified follow‐up time) or had a recorded death indicator in the patient record. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Pearson Exact method. Additionally, patients were analyzed in six prespecified defined neutralization subgroups (Table S1).

The Kaplan–Meier method estimated the cumulative death rate and the log‐rank statistic assessed the efficacy of high versus low titer CCP. Additionally, a multivariable Cox proportional‐hazards regression model included baseline patient characteristics to explore covariate association with survival. Hazard ratios (HR) greater or less than 1 were interpreted as having an increased or decreased association with survival, respectively. Due to the limited data available on transfused patients following discharge, both analyses assumed survival after discharge, and two‐sided p‐values of 0.05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance for all analyses. Note that p‐values were not corrected for multiple hypothesis testing and were only used to guide the exploratory analysis of the CCP observational data. To assess possible confounding due to the changing standard of care and experience in treating hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 over the course of the enrollment period, logistic regression was used to assess the association of month of transfusion with survival.

All analyses were conducted in R (v3.6, https://www.R-project.org/), using base packages, and the “survminer” package for constructing survival plots.

3. RESULTS

The baseline patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. The majority of 23 118 transfused patients with an available ID50 live viral neutralization titers were aged greater than 40 years (89.7%), male (58.5%), and reported a race of white (51.5%). Because follow‐up data on transfused patients were limited after discharge, data were analyzed for all patients, for patients hospitalized for at least 7‐days, and for patients hospitalized for at least 28 days (Table 2). When censoring patients not hospitalized at least 7‐and 28‐days, patient characteristics remained largely stable, with an increase in older age patients (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

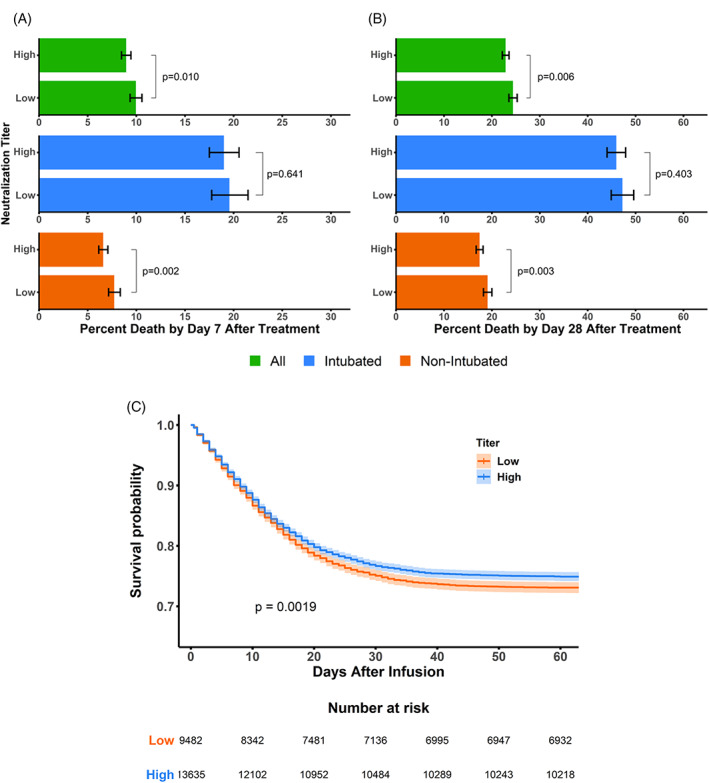

7‐ and 28‐day death rates grouped by broad ID50 titers and intubation status numbers in the “All patient” rows for 7‐day and 28‐day death rates correspond to the horizontal bar graphs displayed in Figure 1, which assumes survival after discharge

| 7‐day mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Titer | Intubation Status | p‐value | |||

| No | Yes | All | ||||

| All patients | 9482 | Low | 7.7 (7.1, 8.4) | 19.6 (17.8, 21.5) | 10.0 (9.4, 10.6) | p = 0.01 |

| 13 636 | High | 6.6 (6.1, 7.1) | 19.0 (17.5, 20.6) | 9.0 (8.5, 9.5) | ||

| Patients hospitalized at least 7 days | 6298 | Low | 13.0 (12.1, 14.0) | 19.1 (17.8, 21.5) | 15.0 (14.1, 15.9) | p = 0.01 |

| 8995 | High | 11.2 (10.4, 12.0) | 19.0 (17.5, 20.6) | 13.6 (12.9, 14.3) | ||

| 28‐day Mortality | ||||||

| Titer | Intubation Status | p‐value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | All | ||||

| All patients | 9482 | Low | 19.1 (18.2, 20.0) | 47.3 (44.9, 49.6) | 24.4 (23.5, 25.3) | p = 0.007 |

| 13 636 | High | 17.4 (16.7, 18.1) | 46.0 (44.0, 48.0) | 22.9 (22.2, 23.6) | ||

| Patients hospitalized at least 28 days | 3319 | Low | 69.9 (67.9, 71.8) | 69.4 (66.8, 72.0) | 69.7 (68.1, 71.3) | p = 0.006 |

| 4666 | High | 66.0 (64.3, 67.7) | 68.2 (65.9, 70.3) | 66.8 (65.5, 68.2) | ||

Note: Mortality was also calculated for patients who had definitive follow‐up time (remained hospitalized or died) at day 7 or day 28, respectively.

In the overall population, when comparing patients transfused with high versus low titer CCP in the overall population, there was a modest but statistically significant 1.0% (95% CI = 0.24, 1.78) absolute reduction in 7‐day mortality (Figure 1A, Table 2), and a 1.5% (95% CI = 0.43, 2.67) absolute reduction in 28‐day mortality (Figure 1B, Table 2). The reduced mortality for patients receiving high versus low titer CCP was also observed when restricting analysis to patients who remained hospitalized over the assessed time frame (i.e., excluding those who were discharged during the observation period). In these populations, we observed a 1.4% (95% CI = 0.29, 2.55) absolute reduction in mortality at 7 days of hospitalization and a 2.9% (95% CI = 0.82, 4.95) absolute reduction in mortality at 28 days of hospitalization, respectively (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

7‐ and 28‐day Death Rates Grouped by Broad ID50 Titers and Intubation Status ‐ Panel A and B report 7‐ and 28‐day death rates, for all patients (assuming survival after discharge), intubated patients, and non‐intubated patients (colored green, blue, and orange, respectfully). Patient death rates were grouped based on prospectively defined titer categories of “high” and “low,” defined as ≥250 and <250 units based on the neutralization titer. The statistical significance in death rates between the titer categories of all CCP transfused patients (green), intubated patients (blue), and non‐intubated patients (orange) was assessed using the Chi‐squared statistic without correction. Panel C reports Kaplan–Meier estimates grouped by high and low Broad ID50 titers. The survival probabilities for all patients (assuming survival after discharge) were plotted for the high (≥250, colored blue) and low (<250, colored orange) titer CCP with 95% confidence intervals shown in a lighter hue. The log‐rank statistic was used as a statistical test to determine differences between the two patient subgroups. The number of patients at risk for the high and low titer subgroups are provided below the plot

Further analysis revealed that the survival benefit was driven by those patients who were not intubated at time of transfusion; they demonstrated 1.8% (95% CI = 0.59, 3.07) absolute risk reduction in 7‐day mortality and 3.9% (95% CI = 1.25, 6.46) absolute risk reduction in 28‐day mortality for high titer compared to low titer (14% and 6% relative risk reductions, respectively). Intubated patients showed no significant difference in survival across CCP titers. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated assuming patient survival after discharge, and similarly, a modest but statistically significant improvement in survival was observed for patients transfused with high titer compared to low titer CCP (Figure 1C, Table S1). Similar trends were observed when stratifying patient survival by the six prespecified neutralization titer subgroups (Table S1), although such trends appeared non‐linear.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model that included CCP titer, ventilation status, days from diagnosis to transfusion, age, gender, race, and HHS region was used to assess covariate association with survival (Table 3). In the analysis, several of the variables in the model, including CCP titer, ventilation status, age, gender, race, and region, were significantly associated with survival when controlling for the other variables. Higher titers were associated with a significant reduction in mortality (HR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.88, 0.97). Patients aged 41–60 years (HR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.73, 2.34), 61–80 years (HR = 4.46, 95% CI = 3.86, 5.16), and 81 years or older (HR = 8.55, 95% CI = 7.34, 9.96) were all more likely to experience death when compared to patients 40 years or younger, with an increasing hazard in each successive age category. Male gender had an increased hazard (HR = 1.17, 1.11, 1.23). HHS region 7 (Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska) (HR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.52, 0.87) and region 8 (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming) (HR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.42, 0.76) were each associated with a decreased risk. Black/African American race was associated with an increased probability of death (HR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.15). Patients also showed a trend in increasing hazard for days from diagnosis to transfusion, albeit non‐significant. To further explore the temporal nature of survival, logistic regression was performed, which revealed that the months after April showed a statistically significant reduction in mortality (Table S2), while the proportions of high versus low titer CCP transfused were similar across the study period (Table S3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable cox regression of patient survival

| HR (95% CI) | p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutralization titer | Low (<250) | 1 | |

| High (≥250) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.97) | 0.003 | |

| Ventilation status | No | 1 | |

| Yes | 3.13 (2.97, 3.31) | <0.001 | |

| Age (Years) | 40 and Under | 1 | |

| 41–60 | 2.02 (1.73, 2.34) | <0.001 | |

| 61–80 | 4.46 (3.86, 5.16) | <0.001 | |

| 81+ | 8.55 (7.34, 9.96) | <0.001 | |

| Days from diagnosis to transfusion | Same Day | 1 | |

| Diagnosis to transfusion | 1 to 3 | 1.00 (0.86, 1.16) | 0.998 |

| 4 to 10 | 1.14 (0.98, 1.32) | 0.094 | |

| 11+ | 1.15 (0.98, 1.35) | 0.082 | |

| Gender | Female | 1 | |

| Male | 1.17 (1.11, 1.23) | <0.001 | |

| Race | White | 1 | |

| Asian | 0.96 (0.83, 1.10) | 0.536 | |

| Black, African American | 1.08 (1.00, 1.15) | 0.039 | |

| Other/Unknown | 1.06 (1.00, 1.13) | 0.058 | |

| HHS region (states) | 1 (ME, MA, CT, RI, NH, VT) | 1 | |

| 2 (NY, NJ, PR, US VI) | 1.26 (0.99, 1.62) | 0.056 | |

| 3 (PA, MD, VA, WV, DE, DC) | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 0.868 | |

| 4 (KY, TN, NC, SC, MI, AL, GA, FL) | 0.93 (0.75–1.17) | 0.548 | |

| 5 (MN, WI, MI, IL, IN, OH) | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | 0.261 | |

| 6 (NM, TX, OK, AR, LA) | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 0.903 | |

| 7 (IA, MO, KS, NE) | 0.67 (0.52–0.87) | 0.003 | |

| 8 (MT, ND, SD, WY, CO, UT) | 0.56 (0.42–0.76) | <0.001 | |

| 9 (CA, NV, AZ, HI) | 1.07 (0.85–1.34) | 0.550 | |

| 10 (WA, OR, ID, AK) | 0.78 (0.56–1.08) | 0.141 |

Note: Results were analyzed by overall survival (hazard ratio for death) within the subgroups. p‐values that are italicized indicate a significant difference compared to the reference category, which are denoted by a hazard ratio of “1”.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study was able to leverage the expected random distribution of neutralization titers in CCP transfused under a large EAP to explore for early signals of efficacy. The results demonstrate an overall modest survival benefit associated with transfusion of high titer CCP compared to low titer in individuals who were not intubated and presumably earlier in the COVID‐9 disease course.

While similar analyses have been previously reported, 30 that study examined a much smaller and minimally overlapping subset of patients enrolled in the EAP (n = 3082), and it used a serologic IgG test rather than the live viral neutralization test used herein. Our study adds to those analyses by using the live viral neutralization test and assessing a larger and minimally overlapping cohort of subjects treated under the EAP. The strengths of this analysis provide greater precision with respect to CCP biologic activity and power to detect modest treatment effects in the overall heterogenous hospitalized population, which reflect real world use of CCP in the early pandemic.

Additional observational studies and RCTs of CCP were subsequently published or made publicly available through pre‐print posting. In the hospitalized population, RCTs include the PLACID (India), 31 PlasmAr (Argentina), 32 RECOVERY (UK), 33 REMAP‐CAP (UK), 34 CONCOR‐1 (Canada, US, Brazil), 35 TSUNAMI (Italy), 36 ConPlas‐19 (Spain), 37 CAPSID (Germany), 38 DAWn‐Plasma (Belgium), 39 Balcells et al (Chile), 40 Ray et al (India), 41 Bennett‐Guerrero et al. (US), 42 and CONTAIN (US) 43 trials, which found no improvement in their primary clinical endpoints in patients treated with CCP compared to control subjects. In contrast, the PennCCP2 trial (US) 44 found a benefit in the primary clinical endpoint of disease severity and 28‐day mortality, and a double‐blind RCT study by O'Donnell et al., (US and Brazil) 45 found CCP was not associated with significant improvement in day 28 clinical status, but was associated with significantly improved survival. Observational studies 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 have reported mixed findings, but generally suggest that efficacy is more likely with high titer CCP in earlier and less severe disease, 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 or when used in those with impaired immunity. 55 , 56 , 57

Interpretation of RCT data, including those in recent meta‐analyses, 58 , 59 is made challenging for multiple reasons: 1) the use of either untitered plasma or plasma qualified by serologic testing alone, 2) high heterogeneity in study populations and dosing strategies, and 3) the treatment of subjects at a median of 8 days or later where it is now apparent that humoral immune responses are well‐developed in a large proportion of patients. 60 Theoretically, optimal patient and product selection for passive immune therapy (e.g., use of high neutralization titer CCP early in the immune response or early viremic stage, or use in patients with sub‐optimal immune responses) has proven difficult to achieve in large RCTs of CCP reported to date, although subgroup analyses may ultimately be informative. 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 An approach to predict the potential benefit of CCP based on patient characteristics was also recently described, and may assist in identifying individuals who will most benefit from CCP transfusion. 65

While live viral assays are the gold standard for neutralizing antibody titer determination, practical limitations (e.g., BSL‐3 requirements, limited throughput) make it is likely that surrogates are needed for widespread testing of CCP. Several studies have demonstrated positive correlation between serologic titers and neutralization activity, although correlations have varied. 66 , 67 , 68 Serologic assays of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies are included under the CCP emergency use authorization as manufacturing tests to qualify high titer CCP donations, with threshold values correlating with the designation of ‘high’ titer used in the current study (https://www.fda.gov/media/141477/download, Appendix A). Additional assay development and studies on serological correlates of neutralization activity and CCP therapeutic response are needed to further guide CCP manufacture and use. These studies should be prioritized.

Because the EAP was designed to optimize its primary objective of providing access, this exploratory efficacy analysis has notable limitations. First, as a single‐arm study, there was no untreated or placebo‐treated control group for comparison. Therefore, while benefit could be demonstrated when comparing high to low titer, quantifying the relative benefit of CCP treatment with respect to an untreated population is impossible. Furthermore, limited baseline and follow‐up information restricted the ability to characterize specific subgroups or make inferences with respect to discharged subjects. For example, data on baseline serostatus and viral loads were unavailable for the EAP population. Additionally, to facilitate the analysis, only subjects receiving one unit of CCP were included. While there was a trend in increasing hazard for days from diagnosis to transfusion, the reported timing of diagnosis was likely highly heterogeneous and imprecise regarding stage of infection because of evolving hospitalization criteria and testing strategies. Therefore, the reported ‘days from diagnosis’ is unlikely to precisely capture the timing of transfusion since initial infection or symptom onset, and may explain why this parameter, though trending toward favoring earlier treatment, did not reach statistical significance. Finally, neutralization testing was unavailable for all >90 000 transfused units, so the analysis cohort represents a subpopulation of the EAP.

The multivariable regression analyses also confirmed that survival benefit was associated with transfusion of high titer over low titer CCP. Conversely, poorer survival was associated with increasing age, male gender, intubation at time of enrollment, and Black or African American race, which are consistent with prior clinical experience. 67 , 68 , 69 The increased mortality associated with Black or African American race highlights the continued importance of monitoring and addressing health disparities in racial and ethnic minorities. The reduced hazard observed for HHS regions 7 and 8 may be the result of time‐varying regional differences in the epidemiology of COVID‐19 related hospitalizations. 70

The challenges of running an optimal RCT of CCP during a pandemic continue to complicate conclusions about efficacy of CCP. Small trial designs are likely to be underpowered to detect the modest but clinically meaningful benefits demonstrated in this study, and studies of CCP can be limited by designs that often have not considered strain specific neutralization activity, patient weight, and dose and timing of transfusion relative to the initial infection, symptom onset, or the humoral immune response (i.e., recipient serostatus). In any given patient, duration of symptoms is likely to be an imprecise surrogate for the stage of the immune response. Results of studies in the hospitalized population, in which effects may be present only in subgroups, thus need to be considered in the context of the timing of CCP transfusion relative to onset of illness, host immune status, and the neutralizing activity of CCP transfused. Investigation of how to best use CCP, and which patients may most benefit, is ongoing; RCTs, and assessment of subgroups within RCTs, will continue to be vital to determine the potential role of CCP in management of COVID‐19. Despite the limitations, we were able to use RWE to demonstrate an association between high‐titer CCP and better outcomes for patients. Although shown to be only of modest clinical benefit in the present report, in addition to potentially having utility in the treatment of COVID‐19 in immunocompromised individuals, CCP may play a role in the future should variants develop that are not neutralized by other available therapeutics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplementary Tables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Dean Follmann at the National Institutes of Health for his contributions to the study.

Belov A, Huang Y, Villa CH, et al. Early administration of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma with high titer antibody content by live viral neutralization assay is associated with modest clinical efficacy. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(6):770‐779. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26531

Artur Belov and Yin Huang contributed equally to this study.

Funding informationThis work was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Health and Human Services and its agencies, including the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), the National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration, as well as any other agency of the U.S. Government. Assumptions made within and interpretations from the analysis do not necessarily reflect the position of any U.S. Government entity.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757‐1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. COVID‐19 Treatement Guidelines Panel . Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed February 2022.

- 3. Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID‐19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1545‐1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bloch EM, Shoham S, Casadevall A, et al. Deployment of convalescent plasma for the prevention and treatment of COVID‐19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2757‐2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Casadevall A, Dadachova E, Pirofski LA. Passive antibody therapy for infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:695‐703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sullivan HC, Roback JD. Convalescent plasma: therapeutic Hope or hopeless strategy in the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Transfus Med Rev. 2020;34:145‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dzik S. COVID‐19 convalescent plasma: now is the time for better science. Transfus Med Rev. 2020;34:141‐144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maiztegui JI, Fernandez NJ, de Damilano AJ. Efficacy of immune plasma in treatment of argentine haemorrhagic fever and association between treatment and a late neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1979;2:1216‐1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beigel JH, Aga E, Elie‐Turenne M‐C, et al. Anti‐influenza immune plasma for the treatment of patients with severe influenza a: a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:941‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mair‐Jenkins J, Saavedra‐Campos M, Baillie JK, et al. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta‐analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:80‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devasenapathy N, Ye Z, Loeb M, et al. Efficacy and safety of convalescent plasma for severe COVID‐19 based on evidence in other severe respiratory viral infections: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. CMAJ. 2020;192:E745‐E755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imai M, Iwatsuki‐Horimoto K, Hatta M, et al. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:16587‐16595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun J, Zhuang Z, Zheng J, et al. Generation of a broadly useful model for COVID‐19 pathogenesis, vaccination, and treatment. Cell. 2020;182:734‐743.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan JF, Zhang AJ, Yuan S, et al. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in a Golden Syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2428‐2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMahan K, Yu J, Mercado NB, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS‐CoV‐2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2021;590:630‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cross RW, Prasad AN, Borisevich V, et al. Use of convalescent serum reduces severity of COVID‐19 in nonhuman primates. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duan K, Liu B, Li C, et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID‐19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:9490‐9496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID‐19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323:1582‐1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang B, Liu S, Tan T, et al. Treatment with convalescent plasma for critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Chest. 2020;158:e9‐e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murphy M, Estcourt L, Grant‐Casey J, Dzik S. International survey of trials of convalescent plasma to treat COVID‐19 infection. Transfus Med Rev. 2020;34:151‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zheng K, Liao G, Lalu MM, Tinmouth A, Fergusson DA, Allan DS. A scoping review of registered clinical trials of convalescent plasma for COVID‐19 and a framework for accelerated synthesis of trial evidence (FAST evidence). Transfus Med Rev. 2020;34:158‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joyner MJ, Bruno KA, Klassen SA, et al. Safety update: COVID‐19 convalescent plasma in 20,000 hospitalized patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1888‐1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu STH, Lin HM, Baine I, et al. Convalescent plasma treatment of severe COVID‐19: a propensity score‐matched control study. Nat Med. 2020;26:1708‐1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salazar E, Christensen PA, Graviss EA, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 patients with convalescent plasma reveals a signal of significantly decreased mortality. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:2290‐2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abolghasemi H, Eshghi P, Cheraghali AM, et al. Clinical efficacy of convalescent plasma for treatment of COVID‐19 infections: results of a multicenter clinical study. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59:102875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hegerova L, Gooley TA, Sweerus KA, et al. Use of convalescent plasma in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: case series. Blood. 2020;136:759‐762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life‐threatening COVID‐19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:460‐470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gharbharan A, Jordans CCE, GeurtsvanKessel C, et al. Effects of potent neutralizing antibodies from convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized for severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Luchsinger LL, Ransegnola BP, Jin DK, et al. Serological assays estimate highly variable SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralizing antibody activity in recovered COVID‐19 patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e02005‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joyner MJ, Carter RE, Senefeld JW, et al. Convalescent plasma antibody levels and the risk of death from Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1015‐1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agarwal A, Mukherjee A, Kumar G, et al. Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid‐19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicentre randomised controlled trial (PLACID trial). BMJ. 2020;371:m3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simonovich VA, Burgos Pratx LD, Scibona P, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid‐19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:619‐629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abani O, Abbas A, Abbas F, et al. Convalescent plasma in patients admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 (RECOVERY): a randomised controlled, open‐label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2049‐2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Estcourt LJ. Convalescent plasma in critically ill patients with Covid‐19. medRxiv. 2021;2021.06.11.21258760. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bégin P, Callum J, Jamula E, et al. Convalescent plasma for hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and the effect of plasma antibodies: a randomized controlled, open‐label trial. medRxiv. 2021;2021.06.29.21259427. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Menichetti F, Popoli P, Puopolo M, et al. Effect of high‐titer convalescent plasma on progression to severe respiratory failure or death in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2136246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Avendaño‐Solà C, Ramos‐Martínez A, Muñez‐Rubio E, et al. A multicenter randomized open‐label clinical trial for convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e152740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Körper S, Weiss M, Zickler D, et al. Results of the CAPSID randomized trial for high‐dose convalescent plasma in patients with severe COVID‐19. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e152264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Devos T, Van Thillo Q, Compernolle V, et al. DAWn‐plasma investigators. Early high antibody‐titre convalescent plasma for hospitalised COVID‐19 patients: DAWn‐plasma. Eur Respir J. 2021;59(2):2101724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Balcells ME, Rojas L, Le Corre N, et al. Early versus deferred anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 convalescent plasma in patients admitted for COVID‐19: a randomized phase II clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ray Y, Paul SR, Bandopadhyay P, et al. A phase 2 single center open label randomised control trial for convalescent plasma therapy in patients with severe COVID‐19. Nat Commun. 2022;13:383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bennett‐Guerrero E, Romeiser JL, Talbot LR, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 convalescent plasma versus standard plasma in coronavirus disease 2019 infected hospitalized patients in New York: a double‐blind randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1015‐1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ortigoza MB, Yoon H, Goldfeld KS, et al. Efficacy and safety of COVID‐19 convalescent plasma in hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(2):115‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bar KJ, Shaw PA, Choi GH, et al. A randomized controlled study of convalescent plasma for individuals hospitalized with COVID‐19 pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(24):e155114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Donnell MR, Grinsztejn B, Cummings MJ, et al. A randomized double‐blind controlled trial of convalescent plasma in adults with severe COVID‐19. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e150646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Briggs N, Gormally MV, Li F, et al. Early but not late convalescent plasma is associated with better survival in moderate‐to‐severe COVID‐19. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0254453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cho K, Keithly SC, Kurgansky KE, et al. Early convalescent plasma therapy and mortality among US veterans hospitalized with non‐severe COVID‐19: an observational analysis emulating a target trial. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:967‐975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Egloff SAA, Junglen A, Restivo JSA, et al. Association of Convalescent Plasma Treatment with reduced mortality and improved clinical trajectory in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the community setting. medRxiv. 2021;2021.06.02.21258190. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Donato ML, Park S, Baker M, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia treated with high‐titer convalescent plasma. JCI Insight. 2021;6:e143196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sostin OV, Rajapakse P, Cruser B, Wakefield D, Cruser D, Petrini J. A matched cohort study of convalescent plasma therapy for COVID‐19. J Clin Apher. 2021;36:523‐532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sturek JM, Thomas TA, Gorham JD, et al. Convalescent plasma for preventing critical illness in COVID‐19: a phase 2 trial and immune profile. medRxiv. 2021;2021.02.16.21251849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klein MN, Wang EW, Zimand P, et al. Kinetics of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody responses pre‐COVID‐19 and post‐COVID‐19 convalescent plasma transfusion in patients with severe respiratory failure: an observational case‐control study. J Clin Pathol. 2021; jclinpath‐2020‐207356. 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-207356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Salazar E, Christensen PA, Graviss EA, et al. Significantly decreased mortality in a large cohort of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients transfused early with convalescent plasma containing high‐titer anti‐severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) spike protein IgG. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:90‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shenoy AG, Hettinger AZ, Fernandez SJ, Blumenthal J, Baez V. Early mortality benefit with COVID‐19 convalescent plasma: a matched control study. Br J Haematol. 2021;192:706‐713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Senefeld JW, Klassen SA, Ford SK, et al. Use of convalescent plasma in COVID‐19 patients with immunosuppression. Transfusion. 2021;61(8):2503‐2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thompson MA, Henderson JP, Shah PK, et al. Association of Convalescent Plasma Therapy with Survival in patients with hematologic cancers and COVID‐19. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1167‐1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hueso T, Godron AS, Lanoy E, et al. Convalescent plasma improves overall survival in patients with B‐cell lymphoid malignancy and COVID‐19: a longitudinal cohort and propensity score analysis. Leukemia. 2022. 10.1038/s41375-022-01511-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Piechotta V, Iannizzi C, Chai KL, et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID‐19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Janiaud P, Axfors C, Schmitt AM, et al. Association of Convalescent Plasma Treatment with Clinical Outcomes in patients with COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2021;325:1185‐1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sette A, Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19. Cell. 2021;184:861‐880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hamilton FW, Lee T, Arnold DT, Lilford R, Hemming K. Is convalescent plasma futile in COVID‐19? A Bayesian re‐analysis of the RECOVERY randomized controlled trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;109:114‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Horby PW, Mafham M, Peto L, et al. Casirivimab and imdevimab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open‐label, platform trial. medRxiv. 2021;2021.06.15.21258542. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Libster R, Perez Marc G, Wappner D, et al. Early high‐titer plasma therapy to prevent severe Covid‐19 in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:610‐618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Korley FK, Durkalski‐Mauldin V, Yeatts SD, et al. Early convalescent plasma for high‐risk outpatients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1951‐1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Park H, Tarpey T, Liu M, et al. Development and validation of a treatment benefit index to identify hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 who may Bbnefit from convalescent plasma. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2147375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tang MS, Case JB, Franks CE, et al. Association between SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralizing antibodies and commercial serological assays. Clin Chem. 2020;66:1538‐1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Farnsworth CW, Case JB, Hock K, et al. Assessment of serological assays for identifying high titer convalescent plasma. Transfusion. 2021;61:2658‐2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Patel EU, Bloch EM, Clarke W, et al. Comparative performance of five commercially available serologic assays to detect antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2 and identify individuals with high neutralizing titers. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:e02257‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rosenthal N, Cao Z, Gundrum J, Sianis J, Safo S. Risk factors associated with in‐hospital mortality in a US National Sample of patients with COVID‐19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2029058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Asch DA, Sheils NE, Islam MN, et al. Variation in US Hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID‐19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:471‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplementary Tables.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.