Summary:

Worldwide advances in treatment and supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer have resulted in a growing population of survivors growing into adulthood. Yet, this population is at very high risk of late occurring health problems, including significant morbidity and early mortality. Unique barriers to high-quality care for this group include knowledge gaps among both providers and survivors as well as fragmented healthcare delivery during the transition from pediatric to adult care settings.

Background

Over the past five decades, cancer during childhood and adolescence has slowly risen in incidence. In 2020, approximately 300,000 cancers were diagnosed among those age 19 and under, worldwide.1 At the same time, treatment and supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer has improved dramatically. In many settings, cancers which were once uniformly fatal are now treatable. For those diagnosed during childhood in the United States, the overall proportion surviving five years from diagnosis has increased from 77.8% to 82.7% to 85.4% for those diagnosed in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010–2016, respectively.2 Similar successes have been described in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Europe. Notably, for children in low-middle income countries, survival gains have been more modest.3,4

Following cancer diagnosis at a young age, survivors confront a long survivorship phase, often lasting over six decades. Over this follow-up phase, the risk of cancer recurrence decreases whilst the risk of treatment-related health problems increases. Organ systems which are developing during childhood and adolescence can be irreversibly impacted by cancer treatment. Thus, while cure rates among this population are high, many survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer face a long follow-up period with numerous long-term health risks. In 2005, the seminal Institute of Medicine report, “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition,” was published, highlighting this population.5 Since then, a growing body of evidence has documented significantly higher levels of morbidity and early mortality in survivors diagnosed during childhood and adolescence, compared to survivors diagnosed during adulthood (Figure 1).6–10 Among 5,522 survivors of childhood cancer who underwent comprehensive follow-up exams, the cumulative incidence of a severe, disabling, life-threatening or fatal chronic condition was 96%. By age 50, survivors experienced, on average, 17·1 chronic health conditions, including 4·7 graded as severe, disabling, life-threatening or fatal. Additionally, the cumulative burden among survivors was nearly 2-fold greater than matched community-controls (p<0·001).11 Common late effects include cardiovascular disease, respiratory dysfunction, endocrine abnormalities, and subsequent malignant neoplasm (see survivor perspective, Box 1A). Many survivors experience multiple late effects which act synergisticly, such that the burden of morbidity is compounded.12

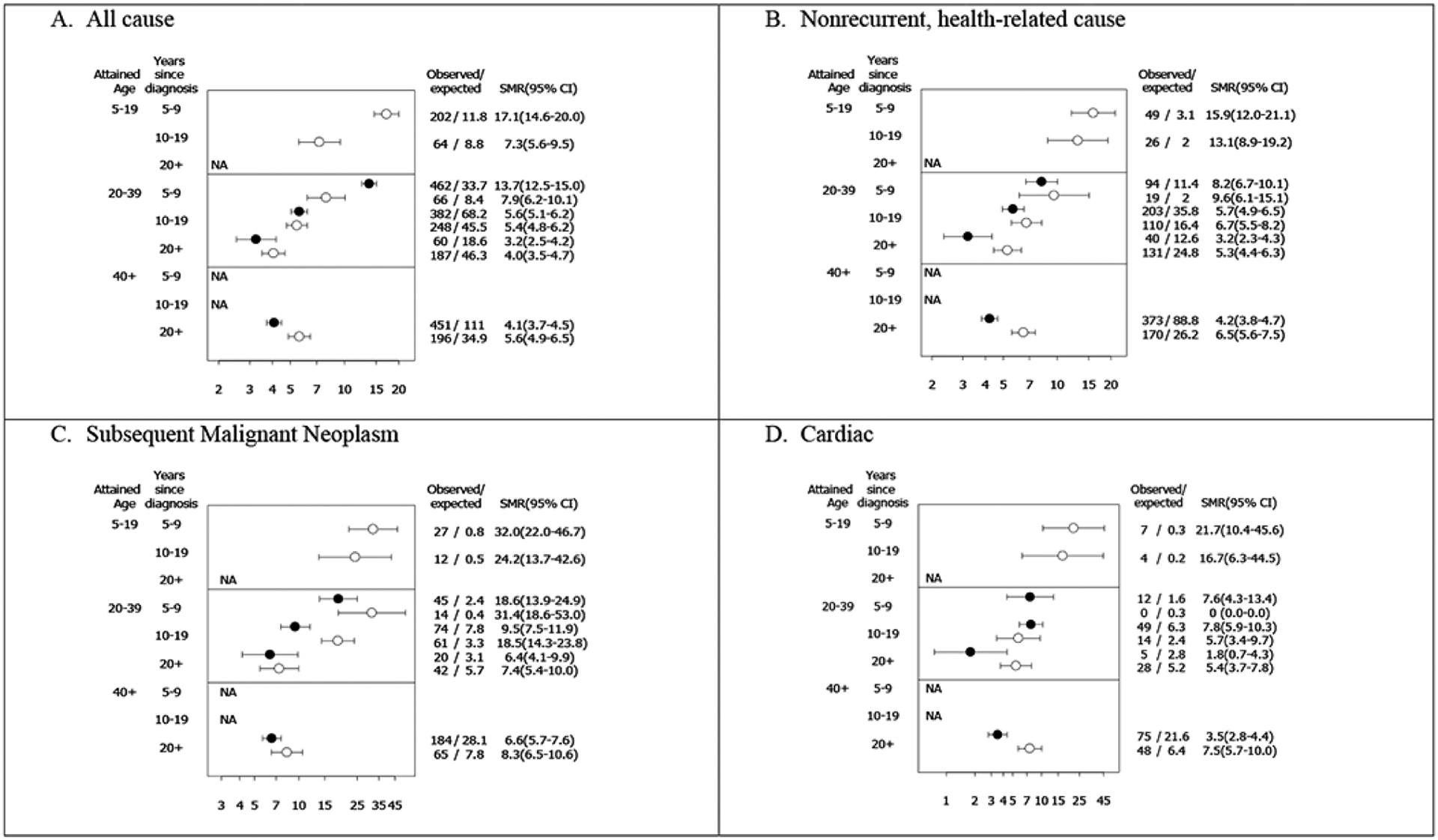

Figure 1. Standardized mortality ratios (SMR) for all-cause; nonrecurrent, health-related cause; subsequent malignant neoplasm; and cardiac mortality among early-AYAs (15–20 years old at diagnosis) and matched childhood cancer survivors (<15 years old at diagnosis) stratified by attained age and time since diagnosis.

Reprinted with permission from Suh, Eugene et al. “Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: a retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.” The Lancet. Oncology vol. 21,3 (2020): 421–435. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30800-9.

Open circles represent childhood cancer survivors; Filled circles represent early-AYA cancer survivors.

NA indicates not possible based on age at diagnosis and follow-up. No cardiac deaths at 5–9 years post diagnosis among childhood cancer survivors age 20–39.

Box 1: The childhood or adolescent cancer survivor perspective.

A. Late effects.

We are more likely to experience cancer a second time and face life-long treatment impacts on our heart, lungs, fertility and sleep. “Brain fog” creates challenges with memory and concentration making it difficult to study or work. We face delays in achieving the goals at which our peers have already succeeded, bringing about changes in relationships and impacting our sense of self-worth. Relationship changes extend to family and partners while establishing new relationships can be difficult as we consider how to share our cancer experience.

“Brain fog is still quite a challenge for me. I can be quite forgetful especially misplacing things and when I get anxious or stressed my concentration is worse. This effects university, work or even doing small things like driving”

“Fatigue is still a big issue for me. Once we recover, we try to “catch up” to the level that our friends have always been, forgetting that recovery can take a long while as there are many factors such as sleep, nutrition and the complexity of our treatment that has such a massive impact”

B. The need for support from the healthcare provider.

While we seek to regain independence, establish new goals and find a new identity after cancer, a number of physical, cognitive, social and emotional issues emerge with limited support to navigate these obstacles.

“The most important thing is to check in regularly that a patient has the right kind of support, whether it be psychosocial support, fertility services, nutrition or any other services that a patient might need in their survivorship phase. At the start of finishing treatment, I felt a bit alone, not only because of a lack of support but also because of the emotional impact from all the side effects of treatment as a young person”

“Open communication between a doctor and patient is necessary, especially in regards to young adults with cancer as we tend develop a sense of comfort and trust”

“It’s important to recognise that everyone is unique and supports should be tailored to meet individual needs”

“Repeating my story caused me a lot of anxiety… meeting someone new and having to rebuild trust was a real anxiety trigger”

“As it was during COVID, I had to go to my fertility appointment alone which was difficult… there was no rapport with the person doing my scan which was disappointing as having egg freezing post cancer treatment can be difficult for any young person to go through. It definitely made me question going back”

C. Care coordination.

While we know we need to manage our long-term health and wellbeing, the pathways to succeed at this are often unclear with insufficient communication between the hospital, our general practitioner and community supports. We worry about the cancer returning and the guilt we feel as survivors when many of our peers have died.

“It was a struggle transitioning from my care team to another care team or GP in the community. The original team understood the little nuances and quirks unique to me and my cancer journey. The new team would always have to spend time to learn it, putting them on the back foot for providing me with the best care”

“I found at the beginning that I felt a bit alone going through this part of my journey, often leaving me with mental health challenges that I had to work through not only because of lack of support but also in having to emotionally deal with the after effects of one of the biggest events or hardships in my young life”

“Although transitioning from a paediatric hospital to an adult hospital after treatment was overwhelming and stressful, I was lucky enough to have a supportive and affirmative team of doctors and nurses. Many of them provided comfort by thoroughly explaining the expectations of the process along with various healthcare workers and teams I could easily contact if I had any questions, concerns or doubts regarding my treatment, appointments, etc.”

D. Recommendations for providers from a childhood cancer survivor.

So what can be done to help assist us to ensure our health and welfare is addressed? Firstly, access to easily understood health information about the long-term risks associated with our cancer treatment and risks of second cancers is critical. Secondly, we require support to manage the lasting impacts on our mental health and relationships. And thirdly we require tailored communication and resources to assist us in navigating health systems and pathways. This will equip us to feel more prepared and less overwhelmed with the shift into survivorship.

“I think it’s important that clinicians understand the various changes and common issues young people are faced with once treatment is finished, therefore providing a variety of resources which they can direct us to and we can easily access would be so helpful”

In addition to the cumulative burden of treatment-related health problems, it is important to consider the how childhood and adolescent cancer survivors differ from adult cancer survivors with regards to developmental stage and age at diagnosis, treatment, and into long-term follow-up. Survivors diagnosed during infancy and the pre-school years may experience interruptions to their early cognitive, emotional and social development. They may begin school already experiencing difficulties with ‘keeping up with peers’13 and may have few memories of life ‘before cancer’. They will grow up to be survivors with limited direct recollection of their cancer treatment and a reliance on parents, siblings, and health professionals to educate them on their future health needs.14 Survivors diagnosed during their primary school years experience a sudden interruption of school and social life, yet have limited experience with which to understand the complexities of their cancer treatment and long term health impacts. For survivors progressing through the developmental tasks of adolescence, cancer can severely interrupt the development of more advanced cognitive skills, identity, independence, romantic relationships and sexuality leading to lifelong challenges in reaching their full potential.15

In this paper, a practical, clinically-oriented overview of childhood and adolescent cancer survivorship is provided. As in the other two papers in this series, the goals are (1) to prepare clinicians to deliver high-quality, holistic care to this unique population of cancer survivors and (2) to highlight healthcare delivery challenges for policy-makers and other stakeholders. Importantly, the majority of research on childhood cancer survivors has been conducted in higher-income countries; this work reflects the existing literature while calling attention to the need for more research in low-resource settings.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for human studies published in English within 2000–2021 with the search terms “child”, adolescent”, “neoplasm”, “survivor*”, “cancer”, “onco*”, “tumour”, “long-term care”, “late effects” and “paediatric”. A search for (child OR adolescent) AND neoplasms AND survivor* identified 9,917 manuscripts; addition of the term “late effects” restricted the search to 1,701 manuscripts. Of these studies, 609 were reported in the years 2016–2022. Studies were selected for relevance to long-term follow-up of childhood cancer survivors; the most recent evidence from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, as well as recommendations from international guideline committees, were prioritized. We excluded studies which did not focus on childhood cancer, addressed issues for children on treatment, or were case reports. During the revision process, we further excluded older studies in favor of updated analyses, where relevant. On the basis of these results, and input from the authors and expert advisers, we included 68 references on on childhood cancer survivorship in this work.

Common Issues and Concerns: Physical

As noted, advances in treatment for childhood cancer have been accompanied by a growing awareness of late-occuring side effects, or late effects. The most widely recognised of these include cardiomyopathy, endocrinopathies, impaired fertility, neurocognitive deficits, and subsequent malignant neoplasms. Nonetheless, late effects can impact every organ system and function.

Children treated at younger ages or when organ systems are still developing are at greater risk of physical late effects. In addition, higher doses typically increase risk, while longer time since treatment is associated with increased prevalence (Figure 1). Radiation therapy (RT)-related late effects typically occur in the region that was exposed to radiation. For example, hypothyroidism is a late effect of RT to the neck. That said, there is wide variability in susceptibility to late effects. With advances in genomics, genetic markers for susceptibility to late effects including ototoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and subsequent neoplasms may become clinically available.16

Two cancer treatment-related late effects, breast cancer and cardiomyopathy, warrant particular attention in long-term follow-up care. A recent publication estimated that female childhood or adolescent cancer survivors who received chest RT have a 30% risk of developing breast cancer by age 50 years, similar to BRCA1 mutation carriers.17 In 2020 the International Guideline Harmonization Group (IGHG) guidelines recommended that female survivors who received a chest RT dose of 10Gy or higher begin annual surveillance with breast MRI and mammography starting at age 25 or 8 years after RT, which ever occurs last.18 Among childhood cancer survivors with history of treatment with anthracyclines and/or chest RT, the risk of cardiomyopathy is increased in a dose-dependent manner,19 beginning at the time of treatment. By 30 years after treatment, as many as one in eight childhood cancer survivors treated with anthracyclines and chest RT will experience a life-threatening cardiovascular event.20 IGHG recommends screening for traditional cardiovascular risk factors and echocardiograms every 2 to 5 years for most survivors exposed to anthracyclines (including mitoxandtrone) or chest RT.19

Of note, the field of pediatric oncology has focused on improving survival while also reducing the risk for long-term toxicity. The conditional life expectancy for five-year survivors of childhood cancer is 48.5 years for 5-year survivors diagnosed in 1970–1979, 53.7 years for those diagnosed in 1980–1989, and 57.1 years for those diagnosed in 1990–1999.21 This has been accomplished by reducing the dose and field size of radiation therapy (RT) while employing newer RT techniques to protect surrounding tissue. Similarly, protocols have been developed to identify favorable or unfavorable diagnoses and use lower cumulative doses for specific agents when clinically appropriate. Thus, cancer subtype and treatment era impact the risk of late effects, with many groups of children and adolescents treated in more recent decades demonstrating less long-term morbidity.

Common Issues and Concerns: Psychological, Cogitive, Social, Fertility and Sexual

Healthcare providers should be aware that childhood and adolescent survivors are at increased risk of developing mental health difficulties. Despite the challenges they have faced, many survivors adjust well after cancer, with up to 75% reporting minimal or even positive impacts on their emotional wellbeing.22 However, a cancer diagnosis during the child and adolescent years coincides with stages of rapid development of essential psychological, cognitive, and social skills. Even with the development of posttraumatic growth and resilience,22 survivors often face formidable mortality and morbidity statistics and a lifetime of ongoing healthcare needs which can impact their mental health.23,24 (Box 1B) A subset of survivors experience symptoms of global distress (up to 25%),13,25 depression (up to 40%),26–28 anxiety (up to 30%),27–29 and post-traumatic stress (up to 70%).29,30 Although the absolute risk remains low, there is also an increased risk for suicide ideation in survivors relative to siblings and controls.22 Survivors who experience multiple late effects,25 have a low income,25 and are not married,31 appear most at risk of developing mental health difficulties. Female survivors appear at particular risk of developing distress/anxiety.22,25

Regular, lifelong screening for mental health difficulties is becoming a key component of effective survivorship care, even at general check ups. Evidence suggests that screening can effectively identify distressed survivors and facilitate referral to appropriate mental healthcare.32 There is little consensus regarding the most appropriate screening tool for this population, so health professionals should select from the wide range of freely available, validated, age-appropriate self-reported measures of mental health and wellbeing (e.g. the Distress Thermometer, which elicits a rating of distress on a simple 1–10 scale – see Emery et. al in this series, Figure 1).33 Survivors with severe symptoms (e.g. suicide ideation) or symptoms that affect daily functioning (e.g. school attendance) need to be identified early and offered immediate treatment with a psychiatrist, psychologist or local mental health team, ideally with experience in oncology.24 For milder difficulties, there is a burgeoning literature reporting moderate improvements in psychosocial outcomes for survivors who participate in group or individual face-to-face34 or online13,35 interventions for young survivors, which can reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress.13,34 Two recent papers of technology-enabled Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors suggest online support is safe, feasible and may be effective for treating depression.35,36

Academic difficulties are also prevalent in survivors, often exacerbated by school absences during treatment and beyond.22 Brain cancer survivors and those who undergo neurotoxic treatment are at particular risk for neurocognitive late effects, displaying impaired attention, reduced processing speed, and more problems with organizational skills and emotion regulation, compared with peers.13,22 Both academic and social difficulties can also result in delayed attainment of milestones such as finishing school, establishing romantic relationships, getting married, and achieving career promotion.22 Regular neuropsychological screening for survivors may therefore be warranted, potentially using a tiered model of brief universal monitoring for all survivors, through to providing referrals for comprehensive evaluation for higher-risk survivors.37 Neurocognitive interventions have achieved moderate success improving proximal outcomes (e.g. working memory), however fewer interventions have successfully improved longer term academic/vocational outcomes for survivors.13,22,38 Social interventions may assist by improving social skills, self-control, social conversations and cooperative play, as well as lowering social rejection and victimization.22

Fertility, body image, sexuality and sexual function can also be significantly disrupted by an early cancer diagnosis.39 Interruptions to pubertal development, menstrual dysfunction and endocrine complications all contribute.40 Reproductive concerns are frequently named as one of the top unmet needs for young cancer survivors.41 Survivors of both child and adolescent cancer report significant fertility-related distress, with many survivors in earlier decades having not received fertility counselling and/or fertility preservation before commencing cancer treatment.40 With regards to sexual function, it is important to consider the survivors’ age at cancer diagnosis. Those diagnosed during childhood are unlikely to have been sexually active before cancer, while older adolescents may experience significant interruption to their sexual development. In the longer term, most survivors appear to do well, although many report experiencing sexual or related symptoms, such as lack of sexual interest, difficulty becoming aroused, difficulty having an orgasm and body image concerns, with female survivors appearing to be at highest risk.42 Timely referral to a reproductive specialist can enable effective fertility-related health prevention, access to assisted reproduction treatment, and management of any hormonal deficiencies, contraception and menstruation issues and symptoms of sexual dysfunction.40

Despite their increased risk of multiple medical late effects, young survivors typically engage in risky health behaviors like tobacco smoking or illicit drug use at a similar, or only marginally lower, rate relative to their peers.22 Screening survivors for substance use in the primary care setting may help to identify survivors who are exacerbating their already significant health risks and facilitate referral to appropriate services (e.g. to support survivors to quit smoking).24 A range of interventions have focused on general healthy lifestyle behaviors such as diet and physical activity, with promising results.22,38 Technology-based solutions, such as remotely delivered physical activity interventions, show promise in this setting, but more research specific to childhood cancer survivors is needed.43 Survivors who know how to advocate for themselves in the healthcare system and who maintain a healthy lifestyle may be better prepared to maximize wellness as they age.

Survivors’ parents and siblings should not be forgotten.13,44,45 A child’s survivorship can be a time of vulnerability for parents, as parents process their family cancer experience and manage downstream effects of having reduced employment, ongoing financial impacts, and new cancer-related worries, such as fear of recurrence.23,30 Parents may experience ongoing psychosocial difficulties, which are often correlated with their child’s difficulties, and sometimes occur at higher rates than in survivors themselves.13,23 Interventions for parents of young survivors are increasing,13,23,38 with promising pilot data44,45 and some larger-scale randomized trials.34,46 Survivorship care providers should consider including screening for psychological concerns and delivering evidence-based psychosocial care for all family members when possible.24

Healthcare Delivery Challenges

In addition to the issues described by Jefford, et. al in this series, some aspects of care delivery for childhood and adolescent cancer survivors are unique. For example, this group of survivors must transition from paediatric to adult-based care. In addition, geographic mobility, engagement into or out of the school or work setting, and cancer identity (or lack thereof) are salient and changing.47 Knowledge gaps in both childhood cancer survivors and their healthcare providers have been well-documented.48 Heathcare delivery challenges, as well as knowledge gaps, appear to be worsened in resource-poor settings and low or middle income countries (LMICs).49 As noted in Jefford, et. al in this series, technology has the potential to enable delivery of high-quality survivorship care but differential access to technology may exacerbate disparities in follow-up.

As a result, many childhood and adolescent cancer survivors do not attend ongoing survivorship care (see Box 1C).50,51 Adherence to recommended testing is suboptimal and declines with age; fewer than half of survivors at highest risk for second cancers and cardiomyopathy receive the recommended surveillance.52 As noted in the other papers in this series, the Institute of Medicine recommendations include provision of a survivorship care plan with individualized follow-up advice for every survivor.[REF: Paper 1 and 2] Yet, evidence regarding the impact of survivorship care plans remains limited.53

As they age, childhood and adolescent cancer survivors transition from pediatric to adult services. The principles and frameworks of successful transition have been described in both adolescents with chronic medical conditions and in childhood cancer survivors.54,55 When done well, transition to adult health service providers can be empowering for survivors and may improve outcomes.56,57 However, given the inherent differences in the structure and culture of pediatric and adult-orientated healthcare, the transition can put survivors at risk for healthcare disengagement and being lost to follow-up.58 This is of particular importance as new health issues may emerge in the transition period or only become apparent after individuals are embedded in the adult sector.11,25,59

A number of key aspects may facilitate optimal transition: transparent plans and processes; utilising patient navigators; adopting a gradual and flexible approach; clear effective communication; promotion of education opportunities for self-management; access to online resources such as tailored roadmaps and treatment summaries; and joint pediatric/adult clinics. Perhaps most salient of these is effective communication, a factor endorsed by both survivors and providers.60 Ensuring that the adult provider has access to the long-term risks of the survivor, care and screening recommendations, and best method for future communication with the paediatric oncology team, if needed, is essential (see below). If available locally, a supportive self-management eHealth intervention such as Oncokompass may be especially helpful.61 The North American “Passport for Care” and the European Survivorship Passport (‘Surpass”) are web-based survivorship care plans. After completion of the treatment summary, ideally with data downloaded from the electronic medical record, built in algorithms, using COG survivorship guidelines or those of the International Guideline Harmonizations Group, suggest which recommendations should be given to the survivor, as well as selected educational materials. Online access to the electronic documents can be granted by the Survivor to medical providers and therefore instantly accessed at a follow-up appointment, regardless of where the providers practice. These and other online initiatives still need to be fully evaluated.

With the growing population of transition-ready childhood and adolescent cancer survivors, and noted in Jefford, et al., transitioning or transferring all childhood and adolescent cancer survivors to a specliast survivorship service is not feasible. Limited evidence from Ontario, Canada suggests specialist survivorship services prevent emergency room use for childhood cancer survivors.62 In many settings, including LMICs, these specialists are not available.49 Yet, keeping childhood and adolescent survivors in the pediatric oncology setting does not facilitate management of non-cancer comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. Therefore, exposure-based risk-stratified approaches have been proposed that match the risks of long term health outcomes with the healthcare setting best suited to provide care (institution-based, community-based, or hybrid models).58,63 For example, individuals who have received therapies associated with a high risk of late effects (e.g haematopoietic stem cell transplantation) may be best transitioned into a specialist survivorship service, whilst patients with low risk of morbidity may be most suited to be followed by primary care providers.64,65 Under those conditions, a supportive self-management eHealth intervention such as Oncokompass may be especially helpful.61

Recommended Approach for Health Care Providers

Prior work suggests that primary care providers, including family and internal medicine physicians, are willing to care for childhood cancer survivors but lack knowledge of late effects and survivorship care resources.66 The principles on how to approach a survivor in clinical consultation are described in detail in the Emery et. al paper in this series. Requesting or eliciting details of the cancer diagnosis and treatment history and addressing comorbities like hypertension apply equally to the childhood or adult cancer survivor. At the same time, being attentive to the unique characteristics of this population (see Box 1D) and utilizing published guidelines for recommendations regarding follow-up testing is paramount.

To that end, providers caring for childhood cancer survivors should be aware of some widely-available resources. The IGHG has published outcome-specific guidelines available at www.ighg.org.67 The relatively small number of childhood cancer survivors, their clinical heterogeneity, and the long latent period before many late effects become clinically apparent limit clinical trials of surveillance approaches.68 Some late effects are not covered in the existing IGHG guidelines but may be encountered in adult-oriented clinical practice. A recent paper from the European PanCareFollowUp group describes European harmonised recommendations for topics (including hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia) where no evidence-based IGHG recommendations exist.69 Notably, this paper has taken a similar approach, with Table 1 including both IGHG and COG recommendations for providers (Part A) and recommendations where no evidence-based guidelines exist but clinical attention is advised (Part B).

Table 1:

Risk-based follow-up recommendations for childhood cancer survivors; guidance for primary care providers.

| System | Treatment and other risk factors | Potential late effects | Recommendations | Prevention/Lifestyle/Advice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory * |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiovascular * |

|

|

|

|

| Endocrine ** |

|

|

|

|

| Fertility (Female) * |

|

|

|

|

| Fertility (Male) * |

|

|

|

|

| Pulmonary ** |

|

|

|

|

| Renal ** |

|

|

|

|

| Skeletal * |

|

|

|

|

| Subsequent malignant neoplasms ** |

|

|

|

|

| Section B. Additional surveillance and late effect consideration with clinical expert advice from the authors. | ||||

| Bladder |

|

|

|

|

| Dental |

|

|

|

|

| Eyes |

|

|

|

|

| Metabolic syndrome (impaired glucose metabolism) |

|

|

|

|

| Neurocognitive |

|

|

|

|

| Peripheral nervous system |

|

|

|

|

| Psychosocial |

|

Depression and mood disorders:

|

Mental health:

|

|

| Skin |

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: COG – Children’s Oncology Group; IGHG – The international Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group; TBI – Total Body Irradiation; PCP - Primary care physician (general practitioner), GVHD – Graft versus host disease, MIBG scan – iodine-131-Metaiodobenzylguanidine scan; TSH – Thyroid stimulating hormone; Gy –Gray; BP – Blood pressure; HP – hypothalamic-pituitary; RT – radiation therapy

These recommendations are briefly stated summaries of the International Guideline Harmonization Group surveillance recommendations, which can be found at IGHG.org

These recommendations are briefly stated summaries of the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidselines, which can be found at www.survivorshipguidelines.org

Providers may further encounter late effects such as dental abdnomalitites, xeropthalmia, cataracts, Reynaud’s phenomenon, neurocognitive difficulties, or peripheral neuropathy, which are attributable to a childhood cancer treatment but are not addressed by the existing IGHG or European PanCareFollowUp efforts. Under these conditions, the North American COG guidelines, which cover a large range of late effects and include both evidence-based and expert opinion, may be helpful (www.survivorshipguidelines.org) and are referenced in Table 1 where IGHG recommendations have not been generated.9,12,70 Other applicable resources and support services are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Finally, providers should be attentive to some routine clinical events that may require special consideration for childhood and adolescent cancer survivors (Table 2). These include requirements for blood transfusion, oxygen supplementation, and considerations for pregnancy.

Table 2.

Potential risk events for clinical consideration in childhood cancer survivors.

| Risk Event | Cancer diagnosis/treatment | Potential late effects | Recommendations | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood product transfusion |

|

|

|

|

| Supplemental oxygen |

|

|

|

|

| Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

| Pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

| Adrenal crisis |

|

|

|

|

| Cerebrovascular accident |

|

|

|

|

Future Directions

The successes of treatment and supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer have resulted in a worldwide population of survivors at risk for myriad late effects. For this group, a growing body of evidence has detailed the lifetime risks of physical and psychological conditions as well as social isolation and premature mortality. Some risk estimates, such as the association of second malignancy with anthracycline chemotherapy, require refinement. Population science to help us better understand individual susceptibility to late effects, whether related to germline genetic factors, epigenetics, or non-cancer related exposures, is needed. In addition, we must support intervention studies to test healthy behaviors, early treatment, or preventive medicine among childhood cancer survivors with a history of high risk therapy (such as RT). With regards to health services research, we need research to formally apply models or implement methods for delivering equitable, well-coordinated, survivor-centered care. Policy work to ensure universal access and adequate payment models for survivorship care is also needed. Finally, research collaborations that include survivors, communities, and other stakeholders are essential.

Supplementary Material

Take Home Points:

(1) Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer are at risk for a range of late-occuring side effects from treatment; (2) these include cardiac, endocrine, pulmonary, fertility, renal, psychological, cognitive, and socio-developmental impairments; (3) care coordination and transition to adult care are significant challenges; (4) resources for adult clinical care teams primary care providers include late effects surveillance guidelines and web-based support services.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank the Victorian & Tasmanian Youth Cancer Action Board (YCAB) for their contribution to the patient perspective (Box 1) included in the manuscript. YCAB comprises a diverse group of twelve young people who have had a cancer diagnosis between the age of 15 and 25. Treated across the Australian paediatric and adult cancer sector and located at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, YCAB represents the collective voice of young people, providing advice to government, the broader health and community sector on issues affecting young people.

Funding:

EST is an employee of the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. KCO is funded by the National Cancer Institute (CA249568; CA134722). CW is supported by a Career Development Fellowship and an Investigator Grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (1143767 and 2008300 respectively).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/ (accessed February 4, 2021 2021).

- 2.National Academies of Sciences EaM. Childhood cancer and functional impacts across the care continuum. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis DR, Siembida EJ, Seibel NL, Smith AW, Mariotto AB. Survival outcomes for cancer types with the highest death rates for adolescents and young adults, 1975–2016. Cancer 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Meer DJ, Karim-Kos HE, van der Mark M, et al. Incidence, Survival, and Mortality Trends of Cancers Diagnosed in Adolescents and Young Adults (15–39 Years): A Population-Based Study in The Netherlands 1990–2016. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(15): 1572–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Jama 2007; 297(24): 2705–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, et al. Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. Jama 2010; 304(2): 172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh E, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, et al. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: a retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21(3): 421–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Fine Licht S, Winther JF, Gudmundsdottir T, et al. Hospital contacts for endocrine disorders in Adult Life after Childhood Cancer in Scandinavia (ALiCCS): a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2014; 383(9933): 1981–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet 2017; 390(10112): 2569–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson TM, Mostoufi-Moab S, Stratton KL, et al. Temporal patterns in the risk of chronic health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed 1970–99: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(12): 1590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel G, Brinkman T, Wakefield C, Grootenhuis M. Psychological outcomes, health-related quality of life, and neurocognitive functioning in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2020; 67(6): 1103–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Jama 2002; 287(14): 1832–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170(5): 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turcotte LM, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Temporal Trends in Treatment and Subsequent Neoplasm Risk Among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer, 1970–2015. Jama 2017; 317(8): 814–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical oncology 2014; 32(21): 2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulder RL, Hudson MM, Bhatia S, et al. Updated Breast Cancer Surveillance Recommendations for Female Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer From the International Guideline Harmonization Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020: JCO. 20.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armenian SH, Hudson MM, Mulder RL, et al. Recommendations for cardiomyopathy surveillance for survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(3): e123–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, van Delden E, et al. High risk of symptomatic cardiac events in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(13): 1429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh JM, Ward ZJ, Chaudhry A, et al. Life Expectancy of Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Over 3 Decades. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6(3): 350–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brinkman TM, Recklitis CJ, Michel G, Grootenhuis MA, Klosky JL. Psychological symptoms, social outcomes, socioeconomic attainment, and health behaviors among survivors of childhood cancer: current state of the literature. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018; 36(21): 2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Bergelt C. Psychosocial interventions for rehabilitation and reintegration into daily life of pediatric cancer survivors and their families: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2018; 13(4): e0196151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lown EA, Phillips F, Schwartz LA, Rosenberg AR, Jones B. Psychosocial Follow-Up in Survivorship as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatric blood and cancer 2015; 62(S5): S514–S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson MM, Oeffinger KC, Jones K, et al. Age-dependent changes in health status in the childhood cancer survivor cohort. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015; 33(5): 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinkman TM, Liptak CC, Delaney BL, Chordas CA, Muriel AC, Manley PE. Suicide ideation in pediatric and adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Journal of neuro-oncology 2013; 113(3): 425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang I-C, Brinkman TM, Kenzik K, et al. Association between the prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013; 31(33): 4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad PK, Hardy KK, Zhang N, et al. Psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes in adult survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015; 33(23): 2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dieluweit U, Seitz D, Besier T, et al. Utilization of psychosocial care and oncological follow-up assessments among German long-term survivors of cancer with onset during adolescence. Klinische Pädiatrie 2011; 223(03): 152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell GA, Salley CG, Barnett M, et al. Anxiety among adolescent survivors of pediatric cancer. Journal of Adolescent Health 2017; 61(4): 409–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer 2011; 117(S10): 2289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lown EA, Phillips F, Schwartz LA, Rosenberg AR, Jones B. Psychosocial Follow-Up in Survivorship as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62 Suppl 5(Suppl 5): S514–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel SK, Mullins W, Turk A, Dekel N, Kinjo C, Sato JK. Distress screening, rater agreement, and services in pediatric oncology. Psychooncology 2011; 20(12): 1324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazak AE, Alderfer MA, Streisand R, et al. Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Their Families: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Family Psychology 2004; 18(3): 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, Bryant RA, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and safety of the Recapture Life videoconferencing intervention for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology 2019; 28(2): 284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang A, Weaver A, Walling E, et al. Evaluating an engaging and coach-assisted online cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A pilot feasibility trial. J Psychosoc Oncol 2022: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy KK, Olson K, Cox SM, Kennedy T, Walsh KS. Systematic Review: A Prevention-Based Model of Neuropsychological Assessment for Children With Medical Illness. J Pediatr Psychol 2017; 42(8): 815–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan D, Chafe R, Hodgkinson K, Chan K, Stringer K, Moorehead P. Interventions to improve the aftercare of survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review. Pediatric Hematology Oncology Journal 2018; 3(4): 90–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson EG, Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, et al. Sexual and Romantic Relationships: Experiences of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2016; 5(3): 286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anazodo AC, Choi S, Signorelli C, et al. Reproductive Care of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer Survivors: A 12-Year Evaluation. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2021; 10(2): 131–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, Termuhlen AM, Shannon SV, Quinn GP. The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer 2015; 121(15): 2529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology 2010; 19(8): 814–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.C IJ, Ottevanger PB, Gerritsen WR, van Harten WH, Hermens R. Determinants of adherence to physical cancer rehabilitation guidelines among cancer patients and cancer centers: a cross-sectional observational study. J Cancer Surviv 2021; 15(1): 163–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakefield CE, Sansom-Daly UM, McGill BC, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of an e-mental health intervention for parents of childhood cancer survivors:“Cascade”. Supportive Care in Cancer 2016; 24(6): 2685–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salem H, Johansen C, Schmiegelow K, et al. FAMily-Oriented Support (FAMOS): development and feasibility of a psychosocial intervention for families of childhood cancer survivors. Acta Oncologica 2017; 56(2): 367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kazak A, Andersen E, Belmonte F, et al. Effect on Parental Distress of a Home-based Psychological Intervention for Families of Children with Cancer (FAMOS): A Nationwide Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2019; 66(Suppl. 4): S50–S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg-Yunger ZR, Klassen AF, Amin L, et al. Barriers and Facilitators of Transition from Pediatric to Adult Long-Term Follow-Up Care in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2013; 2(3): 104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, et al. The role of primary care physicians in childhood cancer survivorship care: multiperspective interviews. The oncologist 2019; 24(5): 710–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tonorezos ES, Barnea D, Cohn RJ, et al. Models of Care for Survivors of Childhood Cancer From Across the Globe: Advancing Survivorship Care in the Next Decade. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(21): 2223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ford JS, Tonorezos ES, Mertens AC, et al. Barriers and facilitators of risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. 2020; 126(3): 619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Signorelli C, Wakefield C, McLoone JK, et al. Childhood cancer survivorship: barriers and preferences. BMJ Supportive Palliative Care 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan AP, Chen Y, Henderson TO, et al. Adherence to Surveillance for Second Malignant Neoplasms and Cardiac Dysfunction in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020; 38(15): 1711–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018; 36(20): 2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Escherich G, Bielack S, Maier S, et al. Building a national framework for adolescent and young adult hematology and oncology and transition from pediatric to adult care: report of the inaugural meeting of the “AjET” Working Group of the German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology 2017; 6(2): 194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawyer S, McNeil R, Thompson K, Orme L, McCarthy M. Developmentally appropriate care for adolescents and young adults with cancer: how well is Australia doing? Supportive Care in Cancer 2019; 27(5): 1783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosen DS, Blum RW, Britto M, Sawyer SM, Siegel DM. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2003; 33(4): 309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Escherich G, Bielack S, Maier S, et al. Building a National Framework for Adolescent and Young Adult Hematology and Oncology and Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care: Report of the Inaugural Meeting of the “AjET” Working Group of the German Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2017; 6(2): 194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freyer DR, Brugieres L. Adolescent and young adult oncology: transition of care. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008; 50(5 Suppl): 1116–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ehrhardt MJ, Williams AM, Liu Q, et al. Cumulative burden of chronic health conditions among adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Identification of vulnerable groups at key medical transitions. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021; 68(6): e29030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sadak KT, Gemeda M, Grafelman MC, et al. Identifying metrics of success for transitional care practices in childhood cancer survivorship: A qualitative interview study of parents. Cancer Med 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Hout A, van Uden-Kraan CF, Holtmaat K, et al. Role of eHealth application Oncokompas in supporting self-management of symptoms and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21(1): 80–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sutradhar R, Agha M, Pole JD, et al. Specialized survivor clinic attendance is associated with decreased rates of emergency department visits in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer 2015; 121(24): 4389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(32): 5117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, et al. Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. Bmj 2001; 323(7307): 271–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nathan PC, Hayes-Lattin B, Sisler JJ, Hudson MM. Critical issues in transition and survivorship for adolescents and young adults with cancers. Cancer 2011; 117(10 Suppl): 2335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski K, et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160(1): 11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatric blood & cancer 2013; 60(4): 543–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Landier W, Skinner R, Wallace WH, et al. Surveillance for late effects in childhood cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018; 36(21): 2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Kalsbeek RJ, van der Pal HJH, Kremer LCM, et al. European PanCareFollowUp Recommendations for surveillance of late effects of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer. Eur J Cancer 2021; 154: 316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. Version 3.0. http://wwwsurvivorshipguidelinesorg/2008. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.