Abstract

Most aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) have gain-of-function somatic mutations of ion channels or transporters. However, their frequency in aldosterone-producing cell clusters of normal adrenal gland suggests a requirement for codriver mutations in APAs. Here we identified gain-of-function mutations in both CTNNB1 and GNA11 by whole-exome sequencing of 3/41 APAs. Further sequencing of known CTNNB1-mutant APAs led to a total of 16 of 27 (59%) with a somatic p.Gln209His, p.Gln209Pro or p.Gln209Leu mutation of GNA11 or GNAQ. Solitary GNA11 mutations were found in hyperplastic zona glomerulosa adjacent to double-mutant APAs. Nine of ten patients in our UK/Irish cohort presented in puberty, pregnancy or menopause. Among multiple transcripts upregulated more than tenfold in double-mutant APAs was LHCGR, the receptor for luteinizing or pregnancy hormone (human chorionic gonadotropin). Transfections of adrenocortical cells demonstrated additive effects of GNA11 and CTNNB1 mutations on aldosterone secretion and expression of genes upregulated in double-mutant APAs. In adrenal cortex, GNA11/Q mutations appear clinically silent without a codriver mutation of CTNNB1.

Primary aldosteronism is a major cause of hypertension. This is potentially curable when due to an APA in one adrenal. Conversely, when primary aldosteronism (PA) is overlooked, it leads to resistant hypertension and high cardiovascular risk. The landmark report of somatic gain-of-function mutations in KCNJ5 in 30–40% of APAs was followed by the discovery of further ion channel or transporter mutations, mainly of CACNA1D, ATP1A1 and ATP2B3, and of some clinical, pathological and biochemical differences between KCNJ5-mutant APAs and the others1-4. In particular, KCNJ5-mutant APAs are more common in women and have features resembling the cortisol-secreting cells of physiological zona fasciculata (ZF)5-8. Conversely, APAs with other ion channel mutations are more common in men and resemble the physiological smaller aldosterone-producing cells of adrenal zona glomerulosa (ZG)4,9. Opinion has varied on whether the residual 20–30% of APAs without apparent mutation is due to sampling from parts of an APA that do not express the aldosterone-synthesizing enzyme, CYP11B2, or to the existence of further somatic mutations yet to be discovered8-10. The genes whose mutation increases aldosterone production may differ from those responsible for tumor formation. Several of the former, particularly CACNA1D, are frequently mutated in the aldosterone-producing cell clusters (or nodules) of otherwise normal adrenals11. KCNJ5 mutation was initially proposed to stimulate cell proliferation, as well as aldosterone production1, but the increased calcium entry consequent on mutation stimulates apoptosis rather than proliferation12. Wnt pathway-activating mutations of CTNNB1, encoding β-catenin, are found in ~5% of APAs. β-Catenin is a coactivator for a number of transcription factors, and mutations that prevent phosphorylation of exon-3 residues are regarded as oncogenic in adrenal and other tumors8,10,13,14. However, there are only rare reports of CTNNB1 mutations coexisting with somatic mutations that activate aldosterone production8,15 and, in most APAs with CTNNB1 mutations, these have been apparently solitary13,16. Whether CTNNB1 mutations are able on their own to stimulate autonomous aldosterone production, or coexist with other unidentified mutations, has not been resolved.

Three whole-exome sequencing (WES) studies, which initially found CACNA1D-, ATP1A1-, and ATP2B3-mutant APAs2-4, also reported several other genes mutated in tumor DNA. However, even reinterrogation of the three WES studies together did not identify additional potential pathogenic mutations present in more than one sample. We therefore undertook another WES study of tumor and germline DNA from a new cohort of 41 patients with APA to determine whether there are further genes with recurrent somatic mutation, and whether these are associated with a specific clinical or biochemical phenotype.

Results

Identification of pathogenic somatic mutations in APAs.

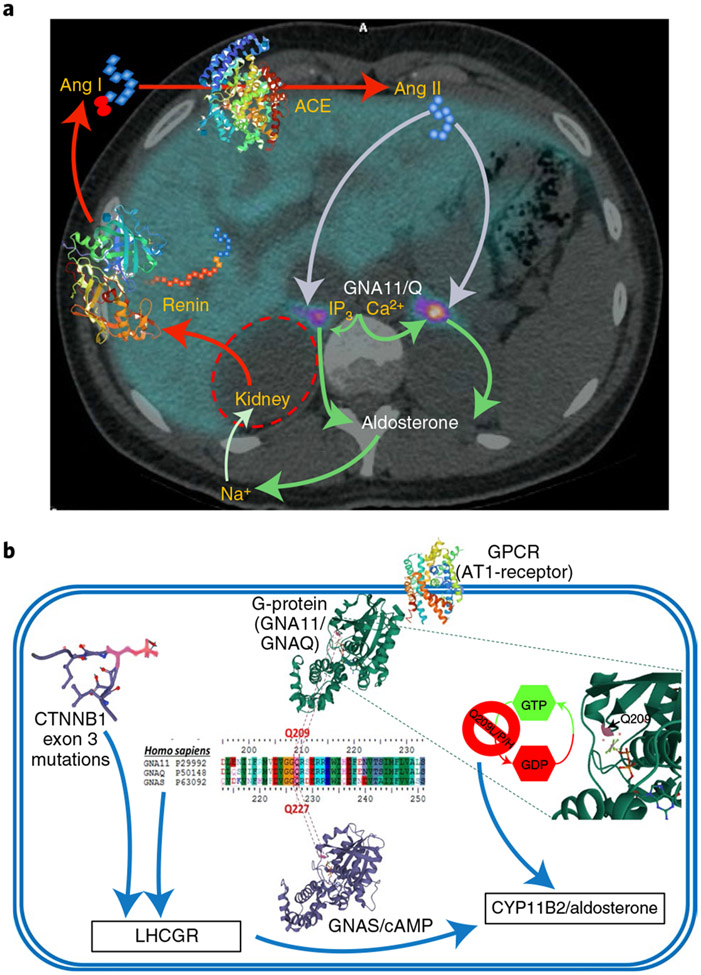

Whole-exome sequencing identified somatic mutations of the four ion channel/transporter genes at known hotspots in 29 of the 41 APAs (Supplementary Table 1). Somatic mutations of CACNA1D were the most frequent (n = 11), followed by KCNJ5 (n = 9), ATP1A1 (n = 5) and ATP2B3 (n = 4). Three APAs had a known mutation of CTNNB1. All three were noted to have a second mutation of the Q209 residue of GNA11, which encodes the G-protein G11. This, or the closely homologous Gq, mediates the aldosterone response to its principal physiological stimulus, angiotensin II (Ang II; Fig. 1a), and the highly conserved p.Gln209 residue is essential for GTPase activation (Fig. 1b)17,18. These mutations cause constitutive G11/q activation.

Fig. 1 ∣. Clinical and cellular schemata showing the critical roles of GNA11/Q, and their p.Gln209 residue, in the production of aldosterone.

a, The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is superimposed on an axial PET CT image through the adrenal glands. The image is taken from the 11C-metomidate PET CT of one of the women whose unilateral (left) double-mutant, aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) was diagnosed by the scan. Renin, a hormone-enzyme, is secreted from the kidneys in response to falls in blood pressure or sodium (Na+). Its substrate, the protein angiotensinogen, is cleaved into an inert decapeptide, Ang I, which is converted on further cleavage by the angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) into the octapeptide, Ang II. This is a potent vasoconstrictor and principal physiological stimulus of aldosterone production in the ZG cells of the outer adrenal cortex. The cellular actions of Ang II are mediated by coupling of its receptor (AT1R) to IP3 and intracellular calcium (Ca2+) release, through a trimeric G-protein whose α-subunit is either Gα11 or Gαq. b, A single cell of a double-mutant APA, illustrating similar two- and three-dimensional (3D) structures of GNA11/Q and GNAS, proximity of the Q209 (GNA11/Q) or Q227 (GNAS) residue to GDP and synergism between somatic mutations of GNA11/Q and CTNNB1, upregulating LHCGR expression and production of aldosterone. The Q209 residue of Gα11 or Gαq (encoded by GNA11 or GNAQ) and analogous residue of other G-proteins is essential for GTPase activity17. 3D structures for GNAQ and GNAS show the p.Gln residue in purple. Somatic or mosaic mutation of p.Gln inhibits GTPase activity and constitutively activates downstream signaling. We find that p.Gln mutation of GNA11/Q stimulates aldosterone production and, in the adrenal, always coexists with somatic mutation in exon 3 of CTNNB1. This prevents inactivation by phosphorylation (for example, of p.Ser33 (in purple), in the partial 3D sequence). Double mutation of GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 induces high expression of multiple genes, including LHCGR, the Gαs/cyclic adenosine monophosphate-coupled receptor of luteinizing and pregnancy hormones. The 3D structures of CTNNB1, GNAS, GNAQ, AT1-receptor, renin and ACE were downloaded from models 6M93, 3C14, 4QJ3, 6YV1, 2V0Z and 1O8A, respectively, at www.rcsb.org/.

Sanger sequencing and replication of GNA11/Q genotype.

UK/Ireland cohort (discovery cohort).

We identified p.Gln209His or p.Gln209Pro mutations of GNA11 in the APAs of four further patients in whom presentation during periods of high luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin (LH/HCG) had prompted the discovery of somatic mutations in exon 3 of CTNNB1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). One patient was indeed our index case of CTNNB1 mutation, detected by our first WES, where the p.Gln209His mutation of GNA11 was reported in the pairwise comparison analysis4. Once we recognized the coexistence of mutations in CTNNB1 and GNA11, and associated features reported herein, targeted sequencing identified somatic exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 and p.Gln209 mutations of either GNA11 or closely homologous GNAQ in three further APAs (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Of the total cohort, one was a 12-year-old boy presenting at puberty while the other nine were women, with presentations in early pregnancy (n = 7) or menopause (n = 1). All ten were completely cured of hypertension postadrenalectomy (Table 1).

Table 1 ∣.

Clinical, biochemical and GNA11/Q genotype findings in the discovery cohort of ten UK/Irish patients with PA and CTNNB1-mutant APA

| Tumor genotype |

Measurements preadrenalectomy |

Measurements postadrenalectomy |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | Sex | Age at surgery (years) |

Onset presentation |

CTNNB1 | GNA11/GNAQ | SBP (mmHg) |

DBP (mmHg) |

Plasma renin (mU l−1) |

Aldosterone (pmol l−1) |

Serum potassium (mmol l−1) |

SBP (mmHg) |

DBP (mmHg) |

Plasma renin (mU l−1) |

Aldosterone (pmol l−1) |

Serum potassium (mmol l−1) |

| GNA11 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | Male | 12 | Puberty | S45F | Q209P | 180 | 120 | <2 | 1,358 | 2.7 | 110 | 75 | 7 | 74 | 4.2 |

| 2 | Female | 35 | Pregnancy | S45P | Q209P | 155 | 85 | <2 | 559 | 2.6 | 123 | 76 | 16 | 283 | 4.0 |

| 3 | Female | 20 | Pregnancy | T41A | Q209H | 215 | 120 | <2 | 1,330 | 2.5 | 121 | 68 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | Female | 34 | Pregnancy | S33C | Q209H | 190 | 100 | <2 | 2,885 | 2.0 | 111 | 69 | 31 | 250 | 4.1 |

| 5 | Female | 26 | Pregnancy | S45F | Q209H | 140 | 86 | <2 | 2,590 | 2.0 | 120 | 70 | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | Female | 52 | Menopause | G34R | Q209P | 190 | 100 | <2 | 672 | 3.1 | 118 | 79 | 9.0 | 158 | 4.1 |

| 7 | Female | 39 | Pregnancy | S45F | Q209H | 160 | 101 | <2 | 2,382 | 2.5 | 120 | 83 | 16.1 | 124 | 4.7 |

| 8 | Female | 41 | S45F | Q209P | 160 | 90 | <2 | 480 | 3.2 | 101 | 65 | 91 | 236 | 4.5 | |

| GNAQ | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | Female | 23 | Pregnancy | G34E | Q209H | 167 | 114 | <2 | 2,000 | 3.3 | 121 | 85 | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 | Female | 26 | Pregnancy | G34R | Q209L | 170 | 110 | <2 | 603 | 4.1 | 123 | 78 | 14 | 408 | 4.7 |

NA, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure. Bold denotes the name of the gene (GNA11 or GNAQ) in which the Q209 mutation was found. Somatic mutations of CTNNB1 and GNA11 in the UK/Irish discovery cohort were detected in patient nos. 1–3 by WES of APAs from 41 patients with PA. Patient nos. 4–6 are the three previously reported women16, with patient no. 4’s somatic mutation of CTNNB1 detected in our first WES4.

French cohort.

We examined 13 APAs from patients in France for mutation at p.Gln209 of either GNA11 or GNAQ. These APAs had previously undergone targeted sequencing and been found to have somatic mutations at exon 3 of CTNNB1. Of these 13 APAs, three had mutations at p.Gln209 of GNA11 and one at p.Gln209 of GNAQ (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1b). During the study, double mutation was suspected in a fifth woman aged 17 years and whose PA dated from puberty; her APA was confirmed to have somatic mutation at p.Gly34 of CTNNB1 and p.Gln209 of GNAQ (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1b). As controls, we genotyped a further nine APAs with known ion channel/transporter gene mutations but found no mutation of CTNNB1. In none of these nine cases was a mutation found in GNA11 or GNAQ.

Table 2 ∣.

Clinical presentation and genotype of GNA11/GNAQ/GNAS in the APA of 17 patients with PA who had CTNNB1-mutant APAs from the replication cohorts

| Replication cohort |

Patient no. |

Sex | Age (years) |

Hypertensive at pregnancy (number of pregnancies) |

Tumor genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTNNB1 |

GNA11 Q209 |

GNA11 R183 |

GNAQ Q209 |

GNAQ R183 |

GNAS Q227 |

GNAS R201 |

|||||

| French cohort | F1 | Female | 29 | Yes (1) | S45F | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT |

| F2 | Male | 40 | – | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F3 | Female | 35 | No (2) | S37C | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F4 | Male | 33 | – | S45A | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F5 | Female | 43 | No (1) | S45F | Q209P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F6 | Female | 45 | Yes (2) | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F7 | Female | 55 | NA | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F8 | Female | 55 | NA | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F9 | Female | 26 | Yesa (1) | S37P | WT | WT | Q209H | WT | WT | WT | |

| F10 | Female | 51 | Yes (1) | S45P | Q209H | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F11 | Male | 36 | – | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F12 | Female | 56 | No (10) | D32Y | Q209H | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F13 | Female | 56 | No (0) | S45Y | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| F14 | Female | 17 | Nob (0) | G34V | WT | WT | Q209H | WT | WT | WT | |

| Swedish cohort | S1 | Female | 55 | Yesc (2) | S45P | WT | WT | Q209H | WT | WT | WT |

| S2 | Female | 59 | NA | S45P | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

| S3 | Female | 26 | NA | S37F | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | WT | |

WT, wild type.

Pre-eclampsia.

Hypertensive at puberty.

Onset at age 24 years preceding first pregnancy.

Swedish cohort.

We achieved further replication by reanalysis of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) FASTQ data from the APAs of a published cohort of 15 Swedish patients19. This included three APAs with somatic mutations of CTNNB1. The reanalysis found one of these to have a p.Gln209His mutation of GNAQ (Table 2). No mutation of GNA11 or GNAQ was seen in the other 12 APAs that had one of the known ion channel/transporter gene mutations19.

In summary, 23/27 patients with CTNNB1-mutant APAs were women, 16 of the 27 (59%) having a mutation at p.Gln209 of GNA11 (n = 11) or GNAQ (n = 5). Among the latter, all were women except for the pubertal boy.

Functional analyses in human adrenocortical cells.

H295R is an immortalized adrenocortical cell line heterozygous for the p.Ser45Pro mutation of CTNNB1 but wild type for GNA11 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Transfection of H295R cells by each of the GNA11 mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2b) increased aldosterone secretion and CYP11B2 expression (encoding aldosterone synthase) by 4.0–6.2- and 3.4–4.2-fold, respectively, compared to wild-type transfected cells (Fig. 2a,b). The stimulatory effect of 10 nM Ang II was retained in the mutant-transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Stimulation of cortisol production by the mutations was less than of aldosterone (Supplementary Fig. 2d,e). To determine whether the Q209 mutations of GNA11 stimulate aldosterone production, even in the absence of CTNNB1 activation, transfections of H295R cells were repeated after either silencing of CTNNB1 using Dharmacon SMARTpool small interfering RNAs or 24-h treatment with the CTNNB1 inhibitor ICG-001 (refs. 20,21). Both interventions reduced aldosterone production relative to vehicle-treated cells, as anticipated from published experiments (Fig. 2c,d)22,23. However, silencing of neither CTNNB1 nor ICG-001 blunted the fold increase in aldosterone secretion seen in mutant-transfected cells compared to wild type (Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Fig. 2f). As a further test of whether GNA11 mutations require coexisting CTNNB1 activation to increase aldosterone production, we used primary adrenocortical cells freshly dispersed from APAs with the wild-type genotype for CTNNB1 and GNA11 (Supplementary Table 2). Cells were transfected with one each of the mutants CTNNB1 and GNA11, or with both mutants together, and compared with cells transfected with vector or wild-type genes. Aldosterone secretion and CYP11B2 expression were increased by the individual mutations, but their combination caused substantially greater increases (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2g). We also studied the p.Gln290His mutation of GNAQ; its transfection into H295R cells increased aldosterone secretion by 1.93-fold (s.e.m. = 0.06) (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2 ∣. Mutations of GNA11/Q Q209 increase aldosterone production in human adrenocortical cells.

a, Transfection of mutations of GNA11 Q209 (Q209L, Q209P and Q209H) into immortalized adrenocortical H295R cells stimulated aldosterone secretion (n = 40 wells examined over five independent experiments, P = 1 × 10−15 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(4) = 105.78). b, CYP11B2 mRNA expression was increased in H295R cells transfected with GNA11 mutations (n = 12–31 biologically independent samples, P = 9 × 10−9 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(4) = 43.34). c, Effect of GNA11 mutations on aldosterone secretion in H295R cells cotransfected with either scrambled siRNA (SiScrambled) or siRNA targeting CTNNB1 (SiCTNNB1) (n = 12–20 biologically independent samples). d, Effect of GNA11 mutations on aldosterone secretion in H295R cells in the presence of either the selective β-catenin inhibitor ICG-001 (3 μM) or vehicle control (n = 10 wells examined over three independent experiments). e, Cells from APA 351 T, wild type for CTNNB1 and GNA11/Q (genotype presented in Supplementary Table 2), were transfected with either wild-type GNA11 (WT) or GNA11 Q209H/L only (Q209H/L) or cotransfected with either wild-type CTNNB1 (WT + WT) or CTNNB1 Δ45 (Δ45). Double mutations increased aldosterone secretion compared to single mutations (n = 3 independent transfections, P = 0.0003 by one-way ANOVA). f, Effect of GNAQ Q209H mutation on aldosterone secretion in H295R cells (n = 10 wells examined over three independent experiments). a,b,f, In box-and-whisker plots, the central line, box and whiskers indicate the median, interquartile range (IQR) and 10th–90th percentile, respectively. For bar charts (c,d) and scatterplots (e), data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. Results for a,b,d,f are expressed as fold change from wild-type untreated transfected cells. Results for c,e are expressed as pM of aldosterone per μg of protein. The exact sample numbers (n) are as indicated below the x axes. P values from Dunn’s multiple comparisons test are as indicated in a,b, whereas those indicated in e are from Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. P values indicated in c,d,f are from two-tailed Student’s t-test. NS, not significant. The data used to generate these plots are provided as a Source data file.

Biochemical phenotype of APAs with double mutations.

LHCGR expression.

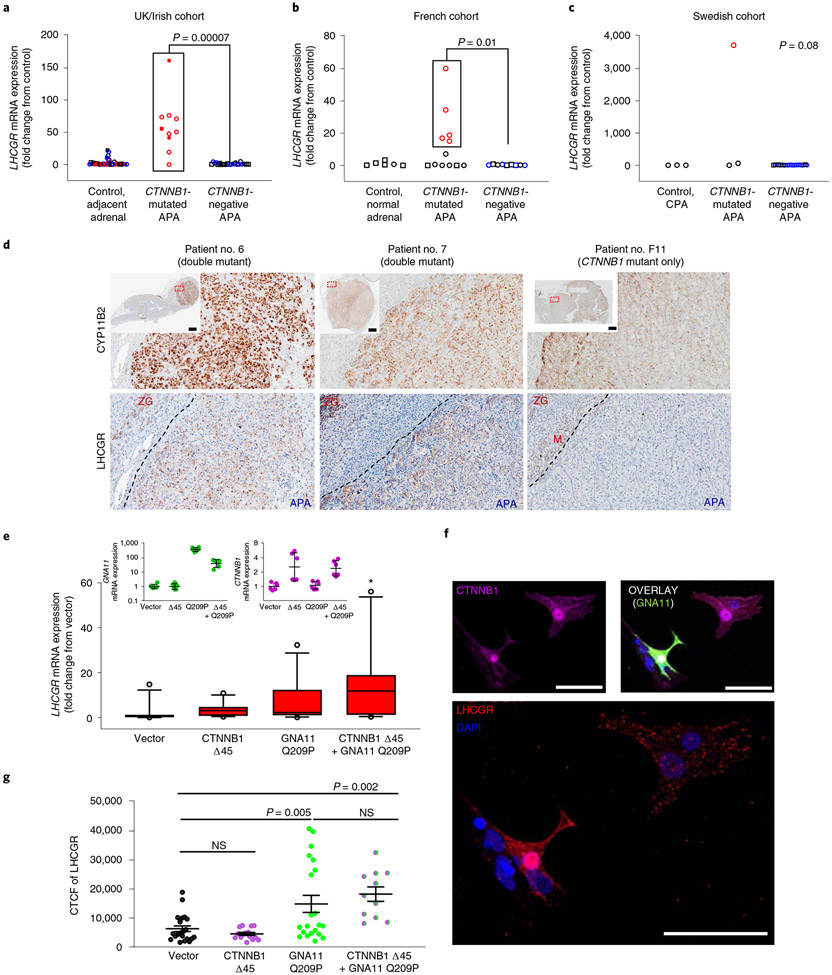

We previously linked the presentation of the first three women at times of high circulating LH or HCG to high expression of the LH and HCG receptor (LHCGR) by CTNNB1-mutant APAs16. To determine whether this association requires double mutation of CTNNB1 and GNA11, rather than CTNNB1 mutation alone, we performed quantitative PCR (qPCR) of LHCGR in all CTNNB1-mutant APAs from the three cohorts. Fold changes >10 (compared to available controls for each cohort) were seen in 15/16 double-mutant APAs (Fig. 3a-c). The exception, patient no. 10, was the sole patient with a p.Gln209Leu mutation. Of possible note, her adrenalectomy coincided with menstruation, when LHCGR expression, at least in ovarian follicles, is suppressed to <10% of maximum24. Conversely, seven of nine single-mutant APAs had low or undetectable LHCGR messenger RNA (P = 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

Fig. 3 ∣. High LHCGR expression in GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 double-mutant adrenal cells.

a, LHCGR mRNA in ten double-mutant, CTNNB1-mutated APAs in the discovery UK/Irish cohort was increased compared to 24 CTNNB1-negative APAs and 34 control adjacent adrenals (P = 0.0001 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(2) = 18.02). b, LHCGR mRNA in five double-mutant APAs in the replication French cohort was increased compared to seven APAs with solitary CTNNB1 mutations, nine CTNNB1-negative APAs and six control normal adrenals (P = 0.003 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(3) = 13.70). c, LHCGR mRNA in one double-mutant APA in the replication Swedish cohort compared to two APAs with only CTNNB1 mutations, 20 CTNNB1-negative APAs and three cortisol-producing adenomas (P = 0.08 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(3) = 6.87). d, LHCGR protein is highly expressed in double-mutant APAs that presented at times of high LH/HCG (for example, patient no. 6 during menopause and patient no. 7 during pregnancy) compared to single CTNNB1-mutant APAs (for example, patient no. F11). Scale bars, 2 mm. e, mRNA of GNA11 (green symbols, n = 6), CTNNB1 (magenta symbols, n = 6) and LHCGR in APA 392 T cells transfected with vector control (n = 11), Δ45 CTNNB1-untagged plasmid (n = 11), Q209P GNA11 GFP-tagged plasmid (n = 12) or cotransfected with both Δ45 CTNNB1 and Q209P GNA11 plasmids (n = 10). LHCGR mRNA was increased in double-mutant cells (P = 0.02 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(3) = 9.78). The central line, box and whiskers indicate the median, IQR and 10th–90th percentile, respectively. Error bars represent geometric mean ± s.d. f, Immunofluorescence of GNA11 (green), CTNNB1 (magenta) and LHCGR (red) from cells transfected as in e. Scale bars, 50 μm. g, CTCF of LHCGR in cells transfected as in e,f. Double-mutant cells had higher CTCF compared to vector control (P = 0.00005 by one-way ANOVA). Exact n numbers indicated below the x axis. Data presented as mean values ± s.e.m. P values from Dunn’s multiple comparisons test indicated in a,b,e (*P = 0.02 comparing vector and double-mutant cells), and Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparison test in g. n represents biologically independent samples. Squares, males; circles, females; open symbols, fresh-frozen/RNAlater-solution-preserved tissues; closed symbols, FFPE tissues; red symbols, double mutants; blue symbols, KCNJ5 mutants; black symbols, KCNJ5 wild type. The data used to generate these plots are provided as a Source data file.

Aldosterone-producing adenomas from the ten UK/Irish patients were positive for LHCGR on immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Expression within APAs was variable, particularly in those with variable expression of CYP11B2. In the APA from patient no. 10, which had low mRNA expression for LHCGR, the protein was concentrated in a visually distinct segment; this allowed demonstration that variation in IHC signal corresponded to fold change on qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Adrenal medulla was also unexpectedly positive, confirmed by analyses of LCM RNA (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Since LHCGR in steroidogenic cells is coupled to both GαS and GαQ/11, the consequences of activation will depend not only on LH/HCG levels but also on downstream signaling and paracrine stimulation by other cell types with physiological expression of LHCGR25. There was also striking heterogeneity in subcellular sites of expression (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Membranous and vesicular expression was most common in double-mutant APAs but cytosolic in adjacent ZG (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

There was no expression of LHCGR in H295R cells, indicating that LH/HCG stimulation in these cells is not essential to the induction of autonomous aldosterone production by GNA11/Q mutation (Fig. 2a,b,f and Supplementary Fig. 3e). The steroidome of H295R cells suggests a cell of origin in the zona reticularis, far downstream of the primordial adrenogenital cells that are the common precursor of the gonads and adrenal cortex26. We therefore turned again to primary adrenocortical cells, comparing LHCGR expression in cells transfected with mutant GNA11 and CTNNB1, alone or together. qPCR showed greater expression of LHCGR in cells transfected with mutations of both genes than with single mutations or vector (Fig. 3e). The low transfection of primary cells also enabled comparison of individual cells, by immunofluorescence, both within and between each well. The red immunofluorescence for LHCGR was qualitatively intense, and frequently membranous, in cells positive for both mutations, but was scarce in green fluorescent protein (GFP)-negative cells lacking the GNA11 p.Gln209 mutation (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 3e-i). Quantitative analysis confirmed a higher LHCGR intensity in cells with GNA11-mutant transfection (Fig. 3g). However some GNA11-mutant cells were LHCGR positive even without CTNNB1 transfection. Post hoc analysis showed that LHCGR (red) intensity was qualitatively and quantitatively associated with immunofluorescence (magenta) for CTNNB1 (Supplementary Fig. 3j), consistent with adrenocortical Wnt activation in PA27,28. When both plasmids were transfected into primary adrenocortical cells, and these were compared by the intensity of green (GNA11) and magenta (CTNNB1), the red (LHCGR) intensity was 31–144-fold higher in cells with GNA11 p.Gln209Pro transfection and high CTNNB1 intensity than in other cells (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Expression of top differentiated genes.

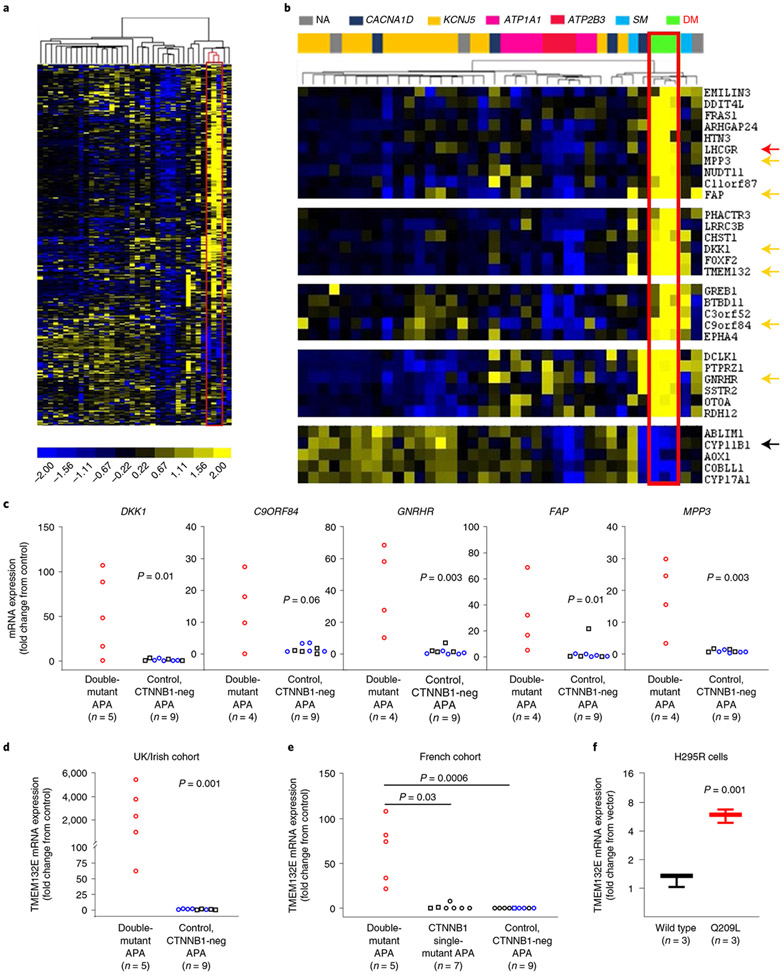

LHCGR was the most upregulated gene (compared to other APAs in the same microarray)16 in the APA of patient no. 4, but a weaker pregnancy association in the replication cohorts (Tables 1 and 2) prompted us to ask whether there are other genes consistently upregulated in double-mutant APAs. We re-examined our previous public-domain expression data (microarray or RNA-seq) performed in three of the double-mutant APAs before their genotype was known: the index case from 2013 (patient no. 4)4,29,30, the APA from a menopausal woman (patient no. 6)5 and the newly diagnosed Swedish double-mutant APA (S1)19. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of the most variably expressed genes in the three studies showed clustering of the three double-mutant APAs, and a high proportion of genes was many-fold upregulated compared to other APAs (Fig. 4a). LHCGR is among several ‘hallmark’ genes with uniquely high expression in the three double-mutant APAs, including the neuronal cell adhesion molecule TMEM132E and the Wnt inhibitor DKK1 (Fig. 4b). Further genes are also upregulated in other ZG-like (compared to KCNJ5-mutant) APAs, or in one or both solitary CTNNB1-mutant APAs. A small number of genes is downregulated in double-mutant APAs, including CYP11B1 (Fig. 4b). This gene encodes the final enzyme in cortisol synthesis (11 β-hydroxylase). Enrichment analysis using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery v.6.8 showed significant enrichment of features or terms concerned with cell junction/cell adhesion or synapse (Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 4 ∣. Gene expression profiles in GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 double-mutant adrenal cells.

a, Heat map representation of 362 DEG with large variance (log2 difference >4) among APAs in at least one of three transcriptome studies (2012 microarray, including patient no. 6 (ref. 5), and 2015 microarray, including patient no. 4 (ref. 16), Swedish RNA-seq19). Each column represents the expression profile of the APA (n = 38). Both genes and individual APAs are hierarchically clustered. The unsupervised cluster analysis of samples, indicated by the bracketing above the heat map, separated the expression profiles of GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 double-mutant APAs (boxed red). Yellow and blue colors indicate high and low expression levels, respectively, relative to the mean (as indicated by the color scale bar). b, Zoomed image of the heat map in a featuring six interesting DEG (yellow arrows) separating double-mutant (DM) APAs from single-mutant APAs (SM) and other APA genotypes. LHCGR (red arrow) and CYP11B1 (black arrow) also clustered double-mutant APAs together. c, The DEG highlighted in b were investigated in double-mutant APAs from the UK/Irish cohort compared to CTNNB1-negative APAs. All, except for C9ORF84 (which had a trend), had significantly higher mRNA expression in double-mutant APAs (the P values indicated are based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test). d–f, DEG TMEM132E mRNA expression was significantly higher in double-mutant APAs from the UK/Irish cohort compared to CTNNB1-negative APAs (d; P = 0.001 by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), in double-mutant APAs from the French cohort compared to CTNNB1 single-mutant APAs (e, P = 0.0002 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(2) = 13.01; P values from Dunn’s multiple comparisons test are indicated), and in GNA11 Q209L-transfected H295R cells compared to GNA11 wild-type-transfected cells (f, P = 0.001 by two-tailed Student’s t-test). Central line, box and whiskers indicate the median, IQR and 10th–90th percentile, respectively. GNA11 mRNA expression in GNA11 Q209L- and wild-type-transfected cells was not significantly different. The exact sample number (n), as indicated below the x axes, represents biologically independent samples. Squares, males; circles, females; red symbols, double mutants; blue symbols, KCNJ5 mutants; black symbols, KCNJ5 wild type.

Quantitative PCR confirmed considerably higher (fold change of tens to thousands) expression of several of the hallmark transcripts in four or five double mutants (from which the RNA of fresh-frozen tissue remained) than in nine APAs without mutations of either gene (Fig. 4c,d) or (for TMEM132E) than in seven APAs with solitary mutation of CTNNB1 (Fig. 4e). However, in H295R cells transfected with mutant GNA11 and with the germline S45P mutation of CTNNB1, TMEM132E was the only one of six genes tested to be significantly and substantially upregulated (Fig. 4f). TMEM132E and LHCGR were the top genes that differed most robustly between double-mutant and other APAs, including those with solitary mutations of CTNNB1 (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4). LHCGR itself remained undetectable after transfection of mutant GNA11.

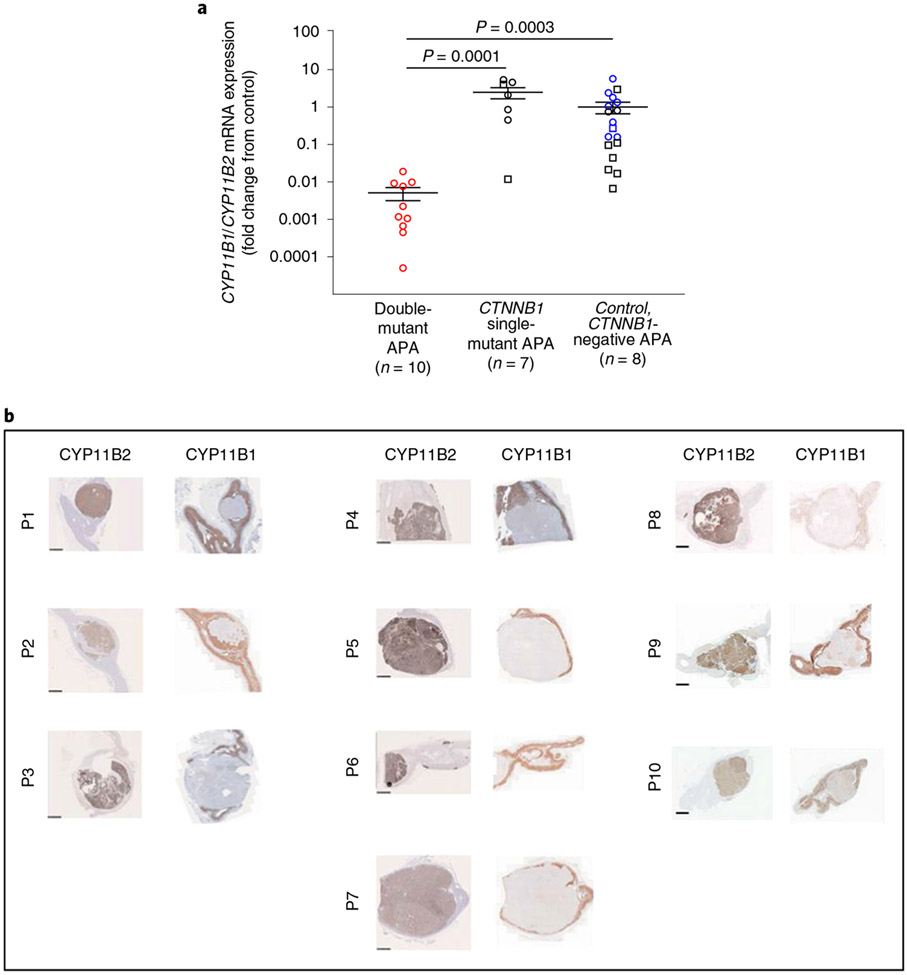

In a previous IHC analysis of eight CTNNB1-mutant APAs, we reported four with low CYP11B2 (H-score < 30) and high CYP11B1 expression (H-score > 200) versus three with high CYP11B2 (H-score > 200) and low CYP11B1 expression (H-score < 1)13. No genotyping was available from these patients, but IHC in two of the current Swedish cohort showed similar contrast between single- and double-mutant APAs (Supplementary Fig. 5a), supported by qPCR and aldosterone measurements (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These findings, and the low CYP11B1 expression highlighted in the heat map of the three double-mutant APAs (Fig. 4b), prompted us to analyze CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 expression in double-mutant APAs compared to APAs with single mutations of CTNNB1 or other genotypes. qPCR confirmed a low CYP11B1/CYP11B2 ratio, and an overall low expression of CYP11B1, in ten double-mutant APAs with available RNA (Fig. 5a). IHC of all the UK/Irish double-mutant APAs showed absent CYP11B1 but strong staining of CYP11B2 (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5 ∣. Expression of aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) and 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) in GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 double-mutant APAs.

a, Quantitative PCR analysis of CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 mRNA expression demonstrated that double-mutant APAs have a lower CYP11B1/CYP11B2 mRNA expression ratio compared to CTNNB1 single-mutant APAs or APAs wild type for CTNNB1 and GNA11/Q (CTNNB1-negative APA) (P = 0.00004 by one-way Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2(2) = 20.23; P values from Dunn’s multiple comparisons test are as indicated). Results are expressed as fold change from CTNNB1 wild-type APAs (CTNNB1-negative APA). Error bars presents mean ± s.e.m. The exact sample number (n), as indicated below the x axis, represents biologically independent samples. Squares, males; circles, females; red symbols, double mutants; blue symbols, KCNJ5 mutants; black symbols, KCNJ5 wild type. b, Immunohistochemistry of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 in the UK/Irish cohort using the primary antibody anti-CYP11B2 and anti-CYP11B1 no. MABS502, clone 80-7. The histotype of high CYP11B2 protein expression and low CYP11B1 expression was apparent, correlating with the low CYP11B1/CYP11B2 mRNA expression seen in a. Scale bars, 2.5 mm.

Phenotype and genotype of adjacent adrenals.

The IHC also showed consistent hyperplasia of adjacent ZG, with absence of both CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 staining but weak/moderate staining for LHCGR (Supplementary Fig. 5c). There were few aldosterone-producing cell clusters, and possible atrophy of ZF. The ZG expansion resembles that in mice with transgenic activation of adrenal Gq or CTNNB1 (refs. 31,32). A similar picture was also seen in a minority of patients with mosaicism of GNAS at the residues analogous to the p.Gln209 or p.Arg183 residues of GNA11/Q (McCune–Albright syndrome)33-35. We therefore wondered whether loci of GNA11 mutation may be present in the adrenal cortex adjacent to APAs with GNA11 mutations at p.Gln209.

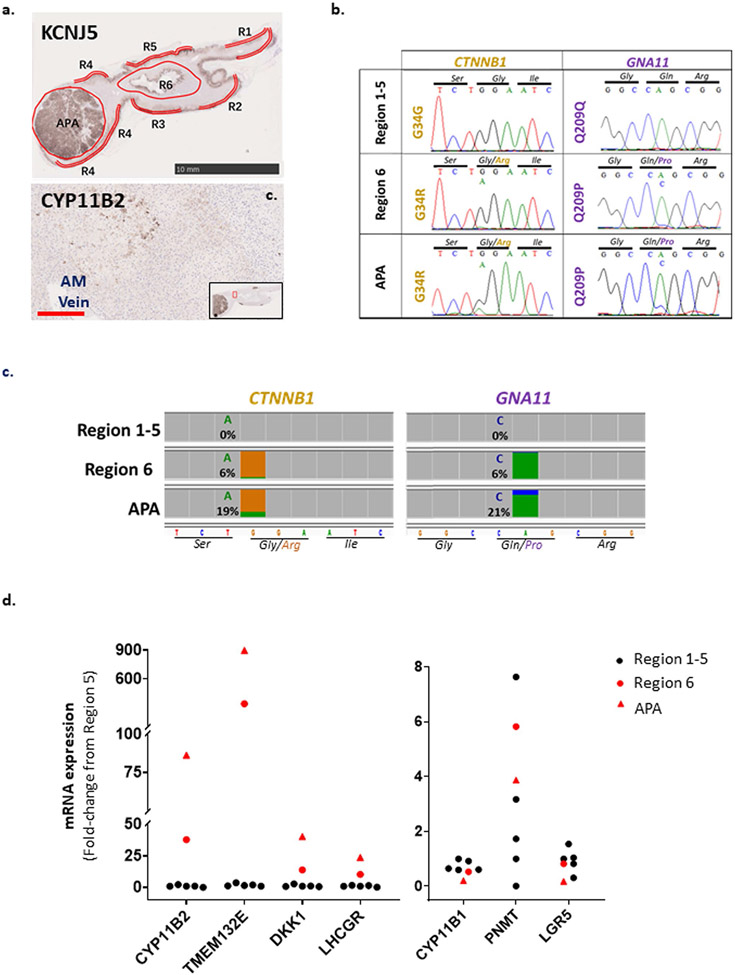

Multiple punch biopsies were taken for genomic DNA (±complementary DNA sequencing and qPCR) from six regions of fresh-frozen adrenal available from patient no. 7 (Fig. 6a-c). Genomic DNA from three regions had the same double-mutation genotype as the original tumor (Supplementary Fig. 6a); in one case, the associated cDNA had low expression of CYP11B2 and LHCGR (Fig. 6b). Samples from the other three regions were CTNNB1 wild type, but one (DNA1) had the same p.Gln209His mutation of GNA11 as the APA, homozygous in R1 genomic DNA and heterozygous in R1 cDNA (Supplementary Fig. 6a and Fig. 6c). The latter had undetectable levels of CYP11B2, LHCGR (Fig. 6b) and other hallmark differentially expressed genes (DEG) high in double-mutant APAs (Supplementary Fig. 6a), confirming its separation from the APA. In patient no. 6, a focal area of perimedullary ZG cells was weakly positive for CYP11B2 (Extended Data Fig. 2a) and for mutations of GNA11 and CTNNB1 (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). qPCR from this double-mutant region showed intermediate expression of several DEG genes (Extended Data Fig. 2d). For more precise analysis and location, we undertook laser-capture microdissection (LCM) of a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) adrenal section from patient no. 1, in which ZG was intact in the adjacent adrenal gland (Fig. 6d,e). Two of eight sites (ZG1 and ZG6) at distinct ends of the adrenal limbs were, respectively, heterozygous or homozygous for the same p.Gln209Pro mutation in GNA11 as the APA, but did not have the APA mutation of CTNNB1 (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 6b). The findings of APA mutations in adjacent adrenal were replicated in each case by up to three quantitative techniques (WES, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for GNA11 and GNAQ and targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) for both tumor genes) (Supplementary Table 4a-d). There was high concordance between ddPCR, NGS and Sanger sequencing when analyzed in the same sample—for example, in patient no. 6 (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Table 4a). Where fresh samples were retaken, concordance with Sanger sequencing was lower—for example, patient no. 1 (Fig. 6d-f and Supplementary Table 4b) and patient no. 7 (Supplementary Table 4a,b)—and NGS detected both tumor genes in some samples. Minor allele frequencies >3% were not seen for other bases in the targeted region or at the same base in other adrenals. No mutations were found in four adrenals adjacent to APAs with KCNJ5 or CACNA1D mutations (Supplementary Table 4d), nor in a limited number of scrapings adjacent to the double-mutant APAs from patient nos. 2, 8 and 9 (Supplementary Table 4b,c).

Fig. 6 ∣. GNA11 somatic mutations were found in adrenals adjacent to double-mutant APAs.

a–c, Patient no. 7. a, Genomic DNA from six different regions (R1–R6) in the fresh-frozen adrenal sample, and associated RNA from regions 1–3 (R1–R3), were genotyped for CTNNB1 and GNA11 mutations. b, qPCR of samples in a showed 135–151-fold lower mRNA expression level of CYP11B2 and 16,102–23,987-fold lower mRNA expression level of LHCGR in R1 cDNA compared to R2 and R3, respectively. DEG highly expressed in double-mutant APAs but lowly expressed in R1 cDNA are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6a. c, Sanger sequencing of samples in a detected solitary GNA11 Q209H mutation in R1 cDNA and double mutations CTNNB1 S45F and GNA11 Q209H in R2 and R3 cDNA. Interestingly, genotyping of R1 genomic DNA (from the same sample as R1 cDNA) detected a homozygous GNA11 Q209H mutation (Supplementary Fig. 6a). d–f, Patient no. 1. d, Patient no. 1 was found to have hyperplastic ZG in adrenal adjacent to double-mutant APA; ZG hyperplasia was demarcated by lack of subcapsular CYP11B1 (visualized using a custom antibody). The hyperplastic ZG was CYP11B2 negative (visualized using a custom antibody) but LHCGR positive (visualized using the antibody NLS1436). This phenotype was consistently present in the UK/Irish discovery cohort (Supplementary Fig. 5c). e, Genomic DNA from the hyperplastic ZG of nine distinct regions of patient no. 1’s adjacent adrenal were collected systematically using segmental LCM of FFPE adrenal sections stained with cresyl violet. f, Solitary heterozygous and solitary homozygous GNA11 Q209P somatic mutations were detected in LCM ZG genomic DNA collected in e from R1 (ZG1 genomic DNA) and R6 (ZG6 genomic DNA), respectively. ZG samples from other regions were wild type for both CTNNB1 and GNA11, along with the other adrenal zones (Supplementary Fig. 6b). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

In McCune–Albright syndrome, GNAS mutation can be difficult to detect and may appear either homozygous, heterozygous or absent at adjacent sites36,37. Finding an APA mutation at disparate sites of adjacent ZG could point to an origin during adrenogenesis, but strictly defined mosaicism is hard to prove within single tissues.

Discussion

We report the discovery of gain-of-function mutations of the G-protein gene GNA11, or its close homolog GNAQ, in multiple APAs. To date, the mutation has always been residue p.Gln209 associated with a gain-of-function mutation of CTNNB1. Mutation of p.Gln209, or homologous p.Gln in GNAS or GNA12-14, impairs hydrogen bonds between G-protein α and β subunits17,18. In ZG, Gq/11 mediate the aldosterone response to Ang II via stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ release by inositol trisphosphate (IP3)38. Somatic mutations of the Gln209 or Arg183 codons of GNA11 or GNAQ have been reported in the majority of uveal melanomas and in several congenital skin or vascular lesions, including blue nevi and Sturge–Weber syndrome39-41. In some congenital lesions the mutation of GNA11/Q is mosaic, being found in several disparate sites42.

The role of Wnt signaling in adrenal development and APA formation is well established28,43,44. Usually Wnt activation in APAs is present without mutation of CTNNB1, but gain-of-function somatic mutations of exon 3 of CTNNB1 are found in ~5% of APAs, as well as in other adrenal tumors10,13,14,27,45,46. Around 20–30% of malignant adrenocarcinomas of the adrenal (ACC) have the same mutations of CTNNB1 as occur in APAs27, but mutations of GNA11/Q are absent from ACCs and their common codriver mutations are in different genes (for example, TP53, MED12)47. In many malignancies codrivers are the exception, often following chemotherapy48,49.

So why do these two well-known oncogenic mutations cluster in APAs but seemingly in no other tumor? Occasional APAs have been reported with dual mutation of CTNNB1 and CACNA1D (ref. 50). However, unlike GNA11/Q, CACNA1D appears to be the sole driver in most APAs where it is mutated, or to coexist with such a variety of mutations that no other gene was recurrently comutated in our 11 CACNA1D-mutant APAs. The greater prevalence of CTNNB1 than GNA11/Q mutations, and the ZG hyperplasia of mice with CTNNB1 mutations, might suggest that GNA11/Q mutations arise in a subset of CTNNB1-mutant APAs51. In possible support, Wnt activation by germline mutation of APC predisposes, rarely, to somatic mutation of KCNJ5 (ref. 52). In potential opposition is the high CYP11B1 expression of solitary CTNNB1-mutant APAs but exceptionally low expression in double mutants, suggesting different sites of origin within the adrenal cortex.

The clue as to whether one mutation generally precedes another may come from growing evidence that increased transcription drives mutation53, and from examples where Gq/11 lie upstream of CTNNB1 activation. As proof of concept, mutation of upstream MAPK in the melanogenesis pathway leads, via second-hit mutation of CTNNB1, to penetrating nevi54. A recent study of p.Gln209 mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma suggested that these cause hyperplasia, “being insufficient for neoplastic transformation” and highlighted clustering of driver mutations within KEGG pathways to explain recurrent second hits55. Coincidentally, GNA11/Q and CTNNB1 feature together in just one KEGG pathway, melanogenesis. Adrenal MC1R expression, and the presence of melanin in occasional pigmented adrenal nodules, seems unlikely to be directly relevant to our double-mutant APAs (refs. 56,57) but the connection between GNAQ and CTNNB1 in melanogenesis is the Wnt receptor FZD6, which is the most upregulated Frizzled in ZG29. An additional potential link between Gq/11 and CTNNB1 activation is through RSPO3 (refs. 58). The RSPO3–LGR5 pathway is active in ZG, possibly controlling cell proliferation and migration as in intestinal crypts29,59-61. In summary, GNA11/Q mutations may arise early and create conditions in which a second hit in CTNNB1 leads to APA formation. Proven examples of GNA11/Q mosaicism—and the disconnected, discrete areas of GNA11 mutation in adjacent hyperplastic ZG—are consistent with this view42. CTNNB1 mosaicism has occasionally been suggested, and much further work is required to determine whether mosaicism for either or both genes might be the antecedent to double-mutant APAs62,63. A case of KCNJ5 mosaicism was recently reported64.

In the replication cohorts from France and Sweden, single-mutant outnumbered double-mutant APAs by two to one, whereas no single-mutant APAs were found among UK patients. The latter came from a variety of endocrine, renal and hypertension clinics, with no apparent referral bias. Ethnic variation in somatic mutation of several genes is recognized in APAs, with KCNJ5 mutations being more common in cohorts of East Asian ancestry than those of European ancestry, and less frequent than CACNA1D in patients of African ancestry, in whom no CTNNB1 mutations are reported to date50,65. Ancestral variation within Europe may seem less likely than between continents. Although melanogenesis is probably irrelevant to adrenal p.Gln209 mutation, MC1R genotype and phenotype (red hair) illustrate intracontinental heterogeneity66.

Our findings suggest that onset of hypertension in the first trimester—the period of peak HCG secretion—should prompt consideration of PA. Most pregnancy-associated hypertension arises in later trimesters. The index case of our original report was successfully managed on amiloride through pregnancy, whereas undiagnosed PA is high risk for both mother and fetus16,67. We previously linked the seemingly explosive presentation of CTNNB1-mutant APAs in early pregnancy to their induction of LHCGR expression. We have not, ourselves, confirmed LH responsiveness of cells transfected with mutant CTNNB1 and GNA11, but LH can induce the CYP11B2 promoter by 25-fold in adrenocortical cells transfected with LHCGR expression16,68. LH stimulates modest increases in aldosterone secretion in some patients with PA, and LHCGR is indeed commonly expressed in APAs and adjacent adrenal—though at a much lower level than in our CTNNB1-mutant APAs presenting in pregnancy16,69,70. Subsequently, it became apparent that CTNNB1 mutation was usually insufficient to cause the phenotype of LH/HCG-dependent PA69,71,72. Our finding of a second driver mutation explains much of the discrepant experience. Although the APA transcriptomes, and transfections of primary cells, show some overlap between phenotypes of single and double mutation, we infer that a double hit within related pathways is more likely than a single hit to cause large increases in expression of LHCGR and of other genes that may influence clinical presentation.

Methods

Patient cohorts.

All patients were confirmed to have PA by raised aldosterone/renin ratio, positive confirmatory tests and lateralization studies (computed tomography/positron emission tomography (CT/PET)73, magnetic resonance imaging and adrenal vein sampling) according to the institutional protocols at the various centers and in accordance with Endocrine Society guidelines74,75. All patients gave written informed consent for genetic and clinical investigation according to local ethics committee guidelines (UK cohort: Cambridgeshire Research Ethics Committee for Addenbrooke’s Hospital, University of Cambridge or the Cambridge East Research Ethics Committee for St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Queen Mary University of London; French cohort: Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris Research Ethics Committee; Swedish cohort: Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala).

UK/Irish cohort.

The seven patients with double mutations of CTNNB1 and GNA11 were among 117 UK/Irish patients who were investigated at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London or Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, or whose operative specimen was received for investigation, during the period 2004–2017.

French cohort.

Patients with PA were recruited between 1999 and 2016 within the Cortico- et Medullo-surrénale, les Tumeurs Endocrines network (COMETE-Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, protocol authorization no. CPP 2012-A00508-35). In total, 198 patients were screened for CTNNB1 mutations. For some of the patients included in this study, the genetic screening of mutations in KCNJ5, ATP1A1, CACNA1D and ATP2B3 was previously described27,76.

Swedish cohort.

Fifteen tumors were selected from a previously documented international cohort19,77. Adrenal specimens were collected from 348 patients from centers in Sweden, Germany, France and Australia.

WES.

Whole-exome sequencing of 40 pairs of APAs and adjacent adrenal from UK patients was conducted in the Barts and London Genome Centre and the Cardiovascular Research Institute of the University of Singapore, with overlap of eight pairs of samples, and previously genotyped controls (n = 3 in each center/institute) as validation of sensitivity (not included in analysis). The 41st APA was analyzed together with germline DNA from blood processed commercially by GATC Biotech. MuTect2 analysis was conducted to identify adrenocortical genes with somatic mutations predicted by sorting intolerant from tolerant and polymorphism phenotyping to be functional. Candidate mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing of DNA from fresh samples of the APA, and sought in other previously genotyped APAs not included in the WES.

Quality control of WES samples.

Genomic DNA of samples was quality assessed by gel electrophoresis, Agilent 2200 Tapestation and Genomic DNA screentape (Agilent Technologies) or as per GATC Biotech standard protocol. Samples with low degradation and a majority of high molecular weight were taken forward for WES.

Patient no. 1.

Using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 Sequencer, WES was conducted on DNA extracted from the APA along with paired germline DNA extracted from venous blood (samples processed commercially by GATC Biotech). WES samples were prepared as an Illumina sequencing library, and sequencing libraries were enriched using the Agilent SureSelectXT Human All Exon V6 Kit. The captured libraries were sequenced and downstream analysis conducted as described below.

Patient no. 2.

Using the Illumina NextSeq 500 Sequencer, WES was conducted on genomic DNA extracted from APAs from 21 patients with PA, along with paired adjacent normal adrenal and APAs from three patients with PA of known genotype (as sensitivity controls). From each DNA sample, 50 ng was processed using the Nextera Rapid Capture Enrichment kit, with the Coding Exome Oligo (CEX) pool. Tagmented DNA was assessed using the Agilent 2200 Tapestation in conjunction with the HSD1000 screentape. All samples showed expected fragmentation profiles, with an average fragment size of 300 base pairs (bp). Enriched libraries were validated using the Agilent 2200 Tapestation in conjunction with the D1000 screentape. Equimolar amounts of each sample library were pooled for sequencing, which was carried out using the llumina NextSeq 500 high-output kit.

Patient no. 3.

Using the Illumina Hiseq 2500 sequencer, WES was conducted on genomic DNA extracted from 27 APAs along with paired adjacent normal adrenal and three APAs of known genotype (as sensitivity controls). GDNA (1 μg) was fragmented using sonication (Covaris, no. S220), optimized to give a distribution of 200–500 bp that was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, no. G2939BA). Library preparation was carried out using a Kapa DNA HTP Library Preparation Kit (KAPA Biosystems, no. 07 138 008 001). Hybridization of adapter-ligated DNA was performed at 47 °C for 64–72 h, to a biotin-labeled probe included in the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Kit (Roche, no. 06465692001). Libraries were sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 2500 sequencing system, and paired-end, 101-bp reads were generated for analysis with 100x coverage per sample.

Data analysis.

Variant calling was performed using Burrows–Wheeler aligner (BWA) v.0.7.12 (for patient 1, 346 T) or v.0.7.15 to align raw reads in the FASTQ files to the human reference genome GRCh37. Alignments were sorted and marked for PCR duplicates using Picard Tools software v.1.119 (for 346 T) or v.1.7. This was followed by base quality score recalibration using the genome analysis toolkit (GATK) for tuning quality scores to reflect higher accuracy of base qualities. For 346 T, ContEst from GATK was used to calculate cross-sample contamination using blood as the ‘normal’ versus each of the APA samples. A panel of normals was created from the blood sample of the 12-year-old boy, using dbSNP and COSMIC as reference. To enrich the panel of normals, we utilized WES of 11 other blood samples, all preprocessed using the protocol described above. Resulting BAMs were analyzed with GATK MuTect v.2 software to identify somatic variants. Normal and tumor pairs were analyzed together when available. For tumor-only samples, the MuTect tumor-only algorithm was used. The contamination estimates derived from ContEst, and the dbSNP, COSMIC, blood sample and panel of normals, were used as resources in the input parameters to filter variants observed in the germline samples. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a threshold coverage of at least ten reads on the respective nucleotide were assessed. Oncotator was used to annotate those variants passing the filters (https://github.com/broadinstitute/oncotator/tree/develop/oncotator).

Reanalysis of RNA-seq data from the Swedish cohort.

RNA-seq as previously described19 was used for variant identification and analyzed for gene expression differentiation.

RNA-seq variant detection.

RNA-seq variant detection was performed following the recommendations on the GATK workflow for RNA-seq variant discovery. RNA-seq reads were aligned to the UCSC hg19 reference genome using the STAR 2-pass method for sensitive novel junction discovery. Picard Tools software (picard-tools-1.119) was then used to sort and mark PCR duplicates on the alignments. The SplitNCigarReads function from GATK was used to reformat alignments, by splitting reads into exon segments, and to reassign reads with good mapping quality into a GATK format. We performed an indel realignment step followed by the quality score recalibration protocol. Variants were called using the HaplotypeCaller from GATK using the ‘--dontUseSoftClippedBases’ parameter and setting the minimum phred-scaled confidence threshold to 20 (-stand_call_conf 20.0). The following hard filters were applied to the called variants: ‘-window 35 -cluster 3 -filterName FS -filter ‘FS > 30.0’ -filter Name QD -filter ‘QD < 2.0”. Variant annotation was performed using ANNOVAR.

Comparison of CTNNB1-only and double mutants.

Gene expression differentiation of the three samples with the CTNNB1 mutation was performed as follows. RNA-seq fastq files were pseudoaligned to the human GRCh37 cDNA reference sequences from ENSEMBL using kallisto v.0.46.0. Transcript abundance was quantified using the kallisto ‘quant’ function with default settings. Gene expression analysis was performed with DESeq2 (v.1.24.0). Genes with fewer than ten reads were removed from further analysis. Dispersion estimates and size factors were calculated using all 15 samples, with gender as a covariate in the design matrix. The two single-mutation samples were then compared to that with a double mutation.

Sanger sequencing of CTNNB1 and GNA11/Q/S.

LCM of adrenal zones.

Freshly sectioned, 10-μm, FFPE adrenal sections of patient no. 1 were used for LCM. Serial adrenal sections were fixed and rehydrated in ethanol then stained with cresyl violet (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 min. The sections were then dehydrated in ethanol and cleaned in Histo-clear II (AGTC Bioproducts). After fixing and staining of adrenal sections, ZG cells were collected by the LCM technique using a Zeiss PALM Microbeam LCM system (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) with PALMRobo v.4.3 software according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All pooled ZG LCM samples collected from the same area of adrenal sections were then stored at −20 °C until RNA and genomic DNA extraction.

Nucleic acid extraction.

Genomic DNA from fresh-frozen/RNAlater-solution-preserved tissue samples was extracted using the Reliaprep gDNA Tissue miniprep system (Promega). gDNA from FFPE samples collected by LCM was extracted using the Arcturus PicoPure DNA Extraction Kit (Applied Biosystems). gDNA of blood from patient nos. 1 and 7 was extracted using the Nucleon BACC3 Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

For the UK/Irish cohort, total DNA-free RNA was isolated from fresh-frozen/RNAlater-solution-preserved samples using TRIzol (Ambion Life Technologies) and the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. The PureLink DNase Set was used in combination to remove DNA from RNA (Invitrogen) by on-column digestion. If fresh-frozen/RNAlater-solution-preserved samples were not available, total RNA and gDNA were extracted from FFPE tissue sample blocks using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (FFPE-extracted DNA/RNA is reported when used). This kit was also used on fresh-frozen samples when RNA and gDNA from the same sample were required. Total RNA from FFPE samples collected by LCM was extracted by the Arcturus Paradise Plus RNA Extraction and Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems) in combination with the PureLink DNase Set, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After extraction, reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA was purified by the DNAclear Purification Kit (Invitrogen).

For the French cohort, total RNA was extracted using Janke and Kunkel’s Ultra-Turrax T25 (IKA Technologies) in Trizol reagent (Ambion Life Technologies) according to the the manufacturer’s recommendations. After treatment with deoxyribonuclease I (Life Technologies), 500 ng of total RNA was retrotranscribed (iScript reverse transcriptase, Bio-Rad).

PCR and sequencing of CTNNB1 and GNA11/Q/S.

Primers used for amplification of CTNNB1, GNA11, GNAQ and GNAS in gDNA and cDNA samples are detailed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6, or as previously described16,76. For the UK/Irish cohort, PCR was performed on 100 ng of DNA in a final volume of a 20-μl reaction using AmpliTaq Gold Fast PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sanger sequencing of PCR products was performed using the LIGHTRUN Tube sequencing service from Eurofins. For the French cohort, PCR was performed on 100 ng of DNA in a final volume of 25 μl containing 400 nM of each primer, 200 μM deoxynucleotide triphosphate and 1.25 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich). Sanger sequencing of PCR products was performed using the Big Dye TM Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI Prism 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sanger Sequencing alignment was performed using GATC Viewer 1.00, BioEdit v.7.2.5 or Sequencher 5.4.6 (Gene Codes).

ddPCR of GNA11/Q.

Specific ddPCR assays for GNA11 (c.627 A > C, c.627 A > T and c.626 A > C) and GNAQ (c.627 A > C and c.627 A > T) mutation detection were designed on Bio-Rad’s Digital Assay Site. Each ddPCR reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 45 ng of DNA template, 1 μl of 20× WT (HEX) and mutant (FAM) assays, 4 U of restriction enzyme HindIII (New England Biolabs) and 10 μl of 2× Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix. The reaction mixture was mixed with 70 μl of Bio-Rad droplet generator oil, partitioned into 15,000–20,000 droplets using the QX-100 droplet generator (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a 96-well PCR reaction plate. PCR conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94 °C and extension for 60 s at 57 °C, at a ramp rate of 2.5 °C s−1, followed by 10 min at 98 °C. The plate was then transferred to a QX-100 droplet reader (Bio-Rad). QuantaSoft software v.1.3.2.0 (Bio-Rad) was used to quantify the copies of target DNA. The ratio of positive HEX to positive FAM events was used to identify the presence and proportion of target mutations.

NGS-targeted sequencing of CTNNB1 and GNA11/Q/S.

French center.

Immunohistochemistry-guided NGS (CYP11B2 IHC-guided NGS) was performed as previously described8. Before DNA extraction from FFPE tissue, APA was identified by CYP11B2 IHC and the areas of interest were delimited and isolated for DNA extraction, by scraping unstained FFPE sections guided by the CYP11B2 IHC slide using a scalpel under a Wild Heerbrugg or Olympus microscope. DNA was extracted from FFPE sections using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen). NGS was performed using an amplicon-based NGS kit on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer as previously described78.

UK center.

Assays were designed using Primers 3’ and 5’ tagged with Fluidigm TSP sequences to allow barcoding and adapter addition. Samples were PCR amplified with FastStart High Fidelity (Roche) under the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles (95 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s) and 72 °C for 5 min on an MJ tetrad MJ225. PCRs were checked on 2% agarose gel; 1 ml of a 1:100 dilution of PCR product was used in a second round of PCR to add barcodes and Illumina adapters with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C, 10 min; 15 cycles (95 °C, 30 s; 60 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s) and 72 °C for 3 min on an MJ tetrad MJ225. Products were quantified by Qubit and loaded onto an Illumina NextSeq 500 to generate in excess of 1,000 × 75-bp paired-end reads. Reads were aligned to human hg38 using BWA, and BAM files visualized in IGV.

WES for validation.

Whole-exome sequencing was performed for validation of certain samples, listed in Supplementary Table 4. Using the Illumina Hiseq 4000, sequencing was conducted on genomic DNA: 1 μg of genomic DNA was fragmented using sonication (Covaris, S220), then optimized to give a distribution of 200–500 bp that was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, no. G2939BA). Library preparation was carried out using the Kapa DNA HTP Library Preparation Kit (KAPA Biosystems, no. 07 138 008 001). Hybridization of adapter-ligated DNA was performed at 47 °C for 64–72 h, to a biotin-labeled probe included in the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Kit (Roche, no. 06465692001). Libraries were sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 4000 sequencing system and paired-end, 150-bp reads were generated for analysis with 200x coverage per sample. Exome data were analyzed using GATK v.3.7 with the human_g1k_v37_decoy as reference genome. Annotation of variants was performed using annovar (v.10-24-2019) and in-house pipelines.

Functional analyses in human adrenocortical cells.

Construction of wild-type and mutant vectors.

GNA11 wild-type and Q209L plasmids was kindly given by R. V. Thakker (University of Oxford), constructed in a pBI-CMV2 vector. CTNNB1 wild-type and del45 (CTNNB1 Δ45) plasmids were kindly given by M. Bienz (University of Cambridge), constructed in a pcDNA3 vector. GNA11 Q209H and Q209P were generated using the NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs), with primers given in Supplementary Table 7, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Functional assays in H295R and primary human adrenal cells.

The human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line H295R and primary human adrenal cells were cultured as previously described16. H295R cells and primary human adrenal cells were transfected with pBI-CMV2 empty vector, GNA11 wild-type and GNA11 Q209H/L/P plasmids, with/or without the cotransfection of CTNNB1 wild-type, CTNNB1 Δ45 plasmids, by electroporation using the Neon Transfection System 10/100 μl Kit (Invitrogen).

For H295R cells, 48 h after transfection the culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium with or without 10 nM Ang II or with 3 or 10 μM of the CTNNB1 inhibitor ICG-001 (AdooQ BioScience). Supernatant was collected for aldosterone measurement after 24 h, and cells were harvested for mRNA expression analysis and protein quantification. For primary adrenal cells, supernatant was collected for aldosterone measurement at 24, 27 (+3), 30 (+6) and 48 (+24) h post transfection, and cells were harvested for mRNA expression analysis and protein quantification at the last time point (48 h post electroporation). All cells harvested for mRNA expression analysis was kept at −80 °C in Trizol until batch extraction of nucleic acid and protein.

Measurement of aldosterone and cortisol.

Aldosterone secretion by primary human adrenal cells was measured using the Homogeneous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) Aldosterone competitive assay (Cisbio) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Aldosterone secretion was measured on the IDS-iSYS Automated System (no. IS-3300, Immunodiagnostic Systems) for H295R cells at the National University of Malaysia and by the Aldosterone HTRF kit (no. 64ALDC0A, Cisbio) using a FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG labtech) at Queen Mary University of London for primary adrenal cells. Cortisol levels were measured using ECLIA-Technology (Cobas e411, Roche) and immunoassay for the in vitro quantitative determination of cortisol (no. 06687733 190, Roche). Aldosterone and cortisol results were normalized by protein level as estimated by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Quantitative PCR with reverse transcription analyses.

The UK/Irish cohort and adrenocortical cells.

Messenger RNA expression of genes of interest was quantified using commercially available TaqMan gene expression probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), listed in Supplementary Table 8. Quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) was performed using either the C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler machine (Bio-Rad) or the 7000 SDS (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Results were analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCT method using housekeeping 18S rRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for normalization.

APAs from the French cohort.

Primers used for LHCGR, CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 RT–qPCR are described in Supplementary Table 9. RT–qPCR was performed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad C1000 touch thermal cycler (CFX96 Real Time System) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CFX Manage TM Software v.3.1 (Bio-Rad) was used for qPCR data acquisition. Normalization for RNA quantity and reverse transcriptase efficiency was performed against three reference genes (geometric mean of the expression of Ribosomal 18S RNA, GAPDH and HPRT; primers are described in Supplementary Table 9), in accordance with Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments guidelines79. Quantification was performed using the standard curve method. Standard curves were generated using serial dilutions from a cDNA pool of all samples. Fold change over control adrenals excised from patients who had undergone enlarged nephrectomy for renal carcinoma (LHCGR RT–qPCR) and over non-CTNNB1 mutated APA (CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 RT–qPCR) was then calculated.

Protein expression analyses.

IHC.

The primary antibodies used for IHC were as follows: anti-LHCGR no. NLS1436 (1:200; Novus Biological); anti-CYP11B1 (1:100) and anti-CYP11B2 (1:100), gifted by C. E. Gomez-Sanchez78; two commercial anti-CYP11B2, nos. ab168388 (1:200; Abcam) and MABS1251 (1:2,500; Sigma-Aldrich); and one commercial anti-CYP11B1, no. MABS502 (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich). The secondary antibodies used were as follows: affinity purified goat anti-rabbit antibody for LHCGR antibody, no. BA-1000 (1:400; Vector laboratories); affinity purified horse anti-mouse antibody for CYP11B2 antibody, no. BA-2000 (1:400; Vector Laboratories); and affinity purified rabbit anti-rat antibody for CYP11B1 antibody, no. BA-4001 (1:400; Vector Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence.

Forty-eight hours after electroporation, transfected H295R and primary human adrenal cells were processed for immunofluorescence as previously described16. Cells were incubated with anti-LHCGR no. NLS1436 (1:200; Novus Biologicals) and anti-CTNNB1 no. 610154 (1:100; BD transduction Lab) at room temperature for 1 h, and then with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 (no. A-11011, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) and goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 (no. A-21235, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h. Immunofluorescence was visualized using a Zeiss LSM 710 (for ADR351T and 357 T)/880 (for ADR392T) confocal microscope. A second set of primary antibodies, a combination of anti-LHCGR, no. NBP2-52504 (1:100; Novus Biologicals) and anti-CTNNB1, no. 71-2700 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific), was used for validation of the first set of primary antibodies used. For the second set of primary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 405 (no. A-31553, 1:1,000; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 647 (no. A-21235, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 568 (no. A-11011, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) were used as the secondary antibodies. Zen Blue 21 Edition software (Zeiss) was used for confocal microscopy image acquisition. Quantification of immunofluorescence was performed using (Fiji Is Just) ImageJ v.1.52e Java 1.8.0_66, as published online (https://theolb.readthedocs.io/en/latest/imaging/measuring-cell-fluorescence-using-imagej.html). Cells successfully transfected with Δ45 CTNNB1 was defined based on having a corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for CTNNB1 >100,000.

Statistical analysis.

All parametric data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. For nonparametric data, results are presented as median ± 95% confidence interval or as geometric mean ± 95% confidence interval (for qPCR data only). For parametric data, two-tailed Student’s t-test and either one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical tests were performed depending on the grouping factors. Either the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (when comparing two groups) or the Kruskal–Wallis test (when comparing three or more groups) was used for nonparametric data. Tests for normality/log normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons were performed. All analyses was performed using either GraphPad Prism software (v.7.04 and v.9.0.1) or Microsoft Excel v.2016 (for Student’s t-test). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 ∣. High LHCGR expression in GNA11 and CTNNB1 double mutant co-transfected primary human adrenal cells.

a, APA 351 T cells transfected with CTNNB1 (untagged plasmid) and GNA11 (GFP-tagged plasmid) wild-type or Q209P (red boxed cell). LHCGR and CTNNB1 expression was visualized as in Fig. 3f using the primary antibody rabbit anti-LHCGR #NLS1436 (1:200; Novus Biologicals, UK) and the primary antibody mouse anti-CTNNB1 #610154 (1:100; BD transduction Lab, USA), respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. b, Immunofluorescence of LHCGR in APA 351 T cells was quantified using corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF). LHCGR expression was increased in cells expressing high CTNNB1 and GNA11 Q209P (the exact number, n, of cells quantified from two independent experiment are as indicated below the x-axis; the P-values indicated are according to Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test). High CTNNB1 was determined as CTCF > 10,000. Data are presented as mean values +/− s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 ∣. GNA11 somatic mutations were found in the adjacent adrenals to double-mutant APA of patient 6.

a, From six different regions (R1-5, at the edges of the adrenal cortex, R6 and APA, within the circled areas) in the formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) adjacent adrenal gland, genomic DNA samples of patient 6 were genotyped for CTNNB1 and GNA11 mutations. Immunohistochemistry of KCNJ5 and CYP11B2 were used for region selection. Scale bar, 10 mm and 50 μm as indicated. b, Sanger sequencing identified weak chromatogram peaks of CTNNB1 G34R and GNA11 Q209P somatic mutations in region 6 of the adjacent adrenal gland. c, Next generation sequencing confirmed the CTNNB1 G34R and GNA11 Q209P mutations in region 6 of the adjacent adrenal gland. d, qPCR of R1-6 and APA showed a 337-fold higher of TMEM132E, 38-fold higher of CYP11B2, 14-fold higher of DKK1 and 10-fold higher of LHCGR expression in region 6 compared to region 5. Regions 1-5 have similar expression of the above genes. The APA had the highest expression of CYP11B2, TMEM132E, DKK1, LHCGR and lowest expression of CYP11B1 and LGR5 compared to regions 1–6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The CTNNB1 plasmid was a kind gift of M. Bienz, Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge. The 11C-metomidate positron emission tomography (PET) CT The project was funded in part by the British Heart Foundation through a Clinical Research Training Fellowship (no. FS/19/50/34566) and PhD Studentship (no. FS/14/75/31134), by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) through Senior Investigator award no. NF-SI-0512-10052 (all to M.J.B.) and by NIHR Efficacy and Mechanisms Evaluation Project (no. 14/145/09, to W.M.D., M.G. and M.J.B.) and Barts and the London Charity project (no. MGU0360), to W.M.D. and M.J.B. The project was further funded through institutional support from INSERM, Agence Nationale de la Recherche (no. ANR-15-CE14-0017-03) and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (no. EQU201903007864) to M.-C.Z. and the NIHR Advanced Fellowship (no. NIHR3000098) to H.L.S. E.A.B.A. is a Royal Society-Newton Advanced Research Fellow (no. NA170257/FF-2018-033). R.V.T. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (no. 106995/Z/15/Z) and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Programme. C.P.C. is supported by the NIHR BRC at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry. M.G., A.M., and R.S. are supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC (no. IS-BRC-1215-20014). The research of J.L.K., Z.T. and R.F. was supported by the National Medical Research Council and BRC of Singapore. Research in London and Cambridge, UK, was further supported by the NIHR Barts Cardiovascular BRC (no. IS-BRC-1215-20022) and the Cambridge BRC and BRC-funded Tissue Bank. The research utilized Queen Mary University of London’s Apocrita HPC facility, supported by QMUL Research-IT (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.438045). Assistance from the Endocrine Unit Laboratory of the National University of Malaysia (UKM) Medical Centre, and from L. K. Chin and S. Khadijah (UKM) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00906-y.

Reporting Summary. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00906-y.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00906-y.

Data availability

Source data for Figs. 2a-f and 3a-c,e,g are provided with the paper. The raw RNA-seq dataset analyzed to generate Fig. 4a,b, Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4 is available upon request from the Science for Life Laboratory Data Centre through the link https://doi.org/10.17044/NBIS/G000007. Regulations by the service provider may make access technically restricted to PIs at Swedish organizations. The microarray datasets analyzed to generate Fig. 4a,b are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE64957) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The WES raw data of the 41 APAs and controls investigated for recurrent pathogenic somatic mutation are available from the Sequence Read Archive under accession nos. PRJNA732946 and PRJNA729738. All other raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Choi M et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science 331, 768–772 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beuschlein F et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat. Genet 45, 440–444 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholl UI et al. Somatic and germline CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat. Genet 45, 1050–1054 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azizan EA et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat. Genet 45, 1055–1060 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizan EA et al. Microarray, qPCR and KCNJ5 sequencing of aldosterone-producing adenomas reveal differences in genotype and phenotype between zona glomerulosa- and zona fasciculata-like tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 97, E819–E829 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monticone S et al. Immunohistochemical, genetic and clinical characterization of sporadic aldosterone-producing adenomas. Mol. Cell Endocrinol 411, 146–154 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akerstrom T et al. Novel somatic mutations and distinct molecular signature in aldosterone-producing adenomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 22, 735–744 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Sousa K et al. Genetic, cellular, and molecular heterogeneity in adrenals with aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension 75, 1034–1044 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nanba K et al. Targeted molecular characterization of aldosterone-producing adenomas in White Americans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 103, 3869–3876 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu VC et al. The prevalence of CTNNB1 mutations in primary aldosteronism and consequences for clinical outcomes. Sci. Rep 7, 39121 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimoto K et al. Aldosterone-stimulating somatic gene mutations are common in normal adrenal glands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E4591–E4599 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams TA et al. Visinin-like 1 is upregulated in aldosterone-producing adenomas with KCNJ5 mutations and protects from calcium-induced apoptosis. Hypertension 59, 833–839 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akerstrom T et al. Activating mutations in CTNNB1 in aldosterone producing adenomas. Sci. Rep 6, 19546 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tadjine M, Lampron A, Ouadi L & Bourdeau I Frequent mutations of beta-catenin gene in sporadic secreting adrenocortical adenomas. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 68, 264–270 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omata K et al. Cellular and genetic causes of idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. Hypertension 72, 874–880 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo AE et al. Pregnancy, primary aldosteronism, and adrenal CTNNB1 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med 373, 1429–1436 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalinec G, Nazarali AJ, Hermouet S, Xu N & Gutkind JS Mutated alpha subunit of the Gq protein induces malignant transformation in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell Biol 12, 4687–4693 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutowski S et al. Antibodies to the alpha q subfamily of guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein alpha subunits attenuate activation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by hormones. J. Biol. Chem 266, 20519–20524 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backman S et al. RNA sequencing provides novel insights into the transcriptome of aldosterone producing adenomas. Sci. Rep 9, 6269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiese M et al. The beta-catenin/CBP-antagonist ICG-001 inhibits pediatric glioma tumorigenicity in a Wnt-independent manner. Oncotarget 8, 27300–27313 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou L et al. Multiple genes of the renin-angiotensin system are novel targets of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 26, 107–120 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doghman M, Cazareth J & Lalli E The T cell factor/beta-catenin antagonist PKF115-584 inhibits proliferation of adrenocortical carcinoma cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 93, 3222–3225 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou T et al. CTNNB1 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation and aldosterone secretion through inhibiting Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in H295R cells. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat 19, 1533033820979685 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeppesen JV et al. LH-receptor gene expression in human granulosa and cumulus cells from antral and preovulatory follicles. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 97, E1524–E1531 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breen SM et al. Ovulation involves the luteinizing hormone-dependent activation of G(q/11) in granulosa cells. Mol. Endocrinol 27, 1483–1491 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazdar AF et al. Establishment and characterization of a human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line that expresses multiple pathways of steroid biosynthesis. Cancer Res. 50, 5488–5496 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tissier F et al. Mutations of beta-catenin in adrenocortical tumors: activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is a frequent event in both benign and malignant adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res. 65, 7622–7627 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]