Abstract

Auxiliary CaVβ subunits interact with the pore forming CaVα1 subunit to promote the plasma membrane expression of high voltage-activated calcium channels and to modulate the biophysical properties of Ca2+ currents. However, the effect of CaVβ subunits on channel trafficking to and from the plasma membrane is still controversial. Here, we have investigated the impact of CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a subunits on plasma membrane trafficking of CaV1.2 using a live-labeling strategy. We show that the CaVβ1b subunit is more potent in increasing CaV1.2 expression at the plasma membrane than the CaVβ2a subunit and that this effect is not related to modification of intracellular trafficking of the channel (i.e. neither forward trafficking, nor recycling, nor endocytosis). We conclude that the differential effect of CaVβ subunit subtypes on CaV1.2 surface expression is likely due to their differential ability to protect CaV1.2 from degradation.

Keywords: Calcium channel, Trafficking, CaVβ auxiliary subunits

Introduction

Calcium influx generated by voltage-gated calcium channels plays a critical role in neuronal functions such as excitability and gene transcription [1, 2]. High-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels are formed by assembly of several subunits including the pore forming CaVα1 subunit and auxiliary CaVα2δ and CaVβ subunits [3].

Among HVA channels, CaV1.2 is the most abundant in the mammalian brain [4] and it is localized in clusters in dendritic shafts and spines [5, 6]. Auxiliary CaVβ subunits are key modulators of channel biophysical properties and their targeting to the plasma membrane [7, 8]. Four CaVβ isoforms have been identified and they are all expressed in the brain. They contain 2 highly conserved domains: a Src Homology 3 domain and a guanylate kinase domain and variable N-terminal, Hook and C-terminal domains. The guanylate kinase domain binds to the α-interacting domain (AID) in the intracellular I–II loop of CaVα1 subunits. The binding of CaVβ to the AID protects CaVα1 from degradation by the proteasome [9]. However, the impact of CaVβ subunits on the trafficking of CaV1.2 to and from the plasma membrane is still a matter of debate [10–12].

In this study, we investigated the effects of two CaVβ subunits, the cytoplasmic CaVβ1b subunit and the membrane anchored (palmitoylated) CaVβ2a subunit [13, 14], on plasma membrane trafficking of CaV1.2 using a live-labeling strategy based on a CaV1.2 construct tagged with bungarotoxin binding sites. We show that CaVβ1b is more potent in increasing CaV1.2 expression at the plasma membrane than CaVβ2a and that this effect is not linked to modification of either forward trafficking, recycling or endocytosis. We suggest that the effect of different CaVβ subunits on CaV1.2 surface expression is likely due to their differential ability to protect CaV1.2 from degradation.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

Alpha-bungarotoxin binding sites (BBS: WRYYESSLEPYPD) were inserted between the S5 and the P loop of domain II of CaV1.2 (downstream Q683: FDEMQ-BBS-TRRST) using standard molecular biology techniques. Briefly, two oligonucleotides coding for a BBS and flanked by MluI restriction sites (oligo A: 5ʹ-ACGCGTCGGACCGGTTGGAGATACTACGAGAGCTCCCTGGAGCCCTACCCTGACCGT A-3ʹ; oligo B: 5ʹ-CGCGTACGGTCAGGGTAGGGCTCCAGGGAGCTCTCGTAGTATCTCCAACCGGTCCGA-3ʹ) were synthesized, annealed and cloned into pMT2 CaV1.2 construct (rat brain CaV1.2 from T. Snutch; GenBank: M67515.1) linearized with MluI. Correct orientation and location of oligonucleotide cloning were confirmed by sequencing the plasmids. A triple BBS construct was generated.

Cell culture and transfection

tsA-201 cells were cultured as previously described [15]. Cells were transfected with plasmid encoding rat CaV1.2 (WT or BBS), rat CaVα2δ-1 (GenBank: NM_012919.3) and either rat CaVβ1b (GenBank: NM_017346.1) or rat CaVβ2a (GenBank: NM_053851.1) using the calcium phosphate method. For electrophysiological experiments, cDNA encoding GFP was co-transfected and used as a transfection marker. Apart from dynamin1 K44E [16] which was cloned into pcDNA3.1, all constructs were cloned into the pMT2 vector.

Electrophysiology recordings

Twenty-four hours after transfection, tsA-201 cells were transferred to a 30 °C incubator for 48 h before being used for experiments. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed and analyzed as described previously [15]. Briefly, currents were recorded at room temperature (22–24 °C) using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp 9.2 software. Patch pipettes were filled with a solution containing the following (in mM): 130 CsCl, 2.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 3 Na-ATP, 0.5 Mg-GTP, pH 7.4. The external solution contained the following (in mM): 132.5 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 BaCl2, 10 glucose, pH 7.4. Current–voltage relationships were obtained by applying 250 ms pulses ranged from − 50 to + 50 mV in 5 mV increment from a holding potential of − 100 mV. Current density–voltage relationships were fitted with a modified Boltzmann equation as follows: I = (Gmax × (V − Vrev))/(1 + exp(−(V − V50,act)/k)), where I is the current density (in pA/pF), Gmax is the maximum conductance (in nS/pF), Vrev is the reversal potential, V50,act is the midpoint voltage for current activation and k is the slope factor.

Trafficking assays and confocal microscopy

tsA-201 cells were plated onto glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA) precoated with poly-l-lysine and transfected as described above. After 3 days expression, cells were washed twice with Krebs–Ringer solution with HEPES (KRH) (in mM; 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.1 MgCl2, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 6 Glucose, 25 HEPES, 1 NaHCO3). For endocytosis experiments, cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml α-bungarotoxin Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate (BTX488) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 17 °C for 30 min. The unbound BTX488 was removed by washing with KRH, and the labelled cells were returned to 37 °C. Endocytosis was terminated by fixing the cells with cold 4% PFA in PBS for 5 min, and then permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Cells were blocked with 10% FBS in PBS for at least 30 min and incubated with the primary Ab (rabbit anti-CaV1.2, 1:200, Alomone labs) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were washed and incubated with secondary conjugated Ab anti-rabbit AF594 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, samples were covered with SlowFadeTM Gold antifade mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For the forward trafficking assay, the cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml unlabeled α-bungarotoxin (BTX; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 17 °C for 30 min. The unbound BTX was washed off with KRH, and the cells were then incubated with 10 μg/ml BTX488 in KRH at 37 °C. To stop the reaction, cells were washed twice with cold KRH and then fixed with 4% PFA in PBS. Brefeldin A (BFA; 200 ng/ml (0.71 μM); Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.4% DMSO was added to the cells in FBS-free culture medium for 4 h before the experiment, and during the experiment in KRH buffer. Cells were examined on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using a 63×/1.4 numerical aperture oil-immersion objective in 16-bit mode. Acquisition settings, chosen to ensure that images were not saturated, were kept constant for each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using paired and unpaired Student’s t tests, as appropriate, using SigmaPlot 14.5 or Prism GraphPad. Differences were considered to reach statistical significance when p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

To monitor the trafficking of CaV1.2 to the plasma membrane we introduced α-bungarotoxin binding sites in the extracellular loop of the channel (Fig. 1a). This construct, CaV1.2-BBS, remained functional and generated Ba2+ currents with a density similar to the WT channel (− 9.7 ± 2.0 pA/pF, n = 9, vs − 13.5 ± 2.5 pA/pF, n = 18, for CaV1.2-BBS and WT, respectively; Fig. 1b). However, the insertion of the tag induced a slight increase in the slope of the activation curve (from − 9.3 ± 0.9 mV, n = 9, to − 7.1 ± 0.3 mV, n = 18, for WT and CaV1.2-BBS, respectively, p = 0.007) and a depolarizing shift of the reversal potential (from 37.5 ± 2.6 mV, n = 9, to 48.4 ± 2.4 mV, n = 18, for WT and CaV1.2-BBS, respectively, p = 0.01). The V50,act and the Gmax remained unchanged (V50,act = − 14.5 ± 2.2 mV, n = 9, and − 14.7 ± 0.6 mV, n = 18; Gmax = 0.34 ± 0.08 nS/pF, n = 9, and 0.30 ± 0.05 nS/pF, n = 18, for WT and CaV1.2-BBS, respectively). The effect on reversal potential may be indicative of an effect of the BBS modification on permeability, but this should have little bearing on the utility of this construct for trafficking studies.

Fig. 1.

Effect of CaVβ subunits on CaV1.2 cell surface expression in tsA-201 cells. a Schematic of CaV1.2 channel tagged with bungarotoxin binding site (CaV1.2-BBS, BBS: red triangle) between S5 and the P-loop of domain II (DII). b Representative whole-cell current traces recorded in response to depolarizing steps from − 50 to + 40 mV from a holding potential of − 100 mV from tsA-201 cells expressing either CaV1.2 WT (top traces) or CaV1.2-BBS (bottom traces) together with auxiliary subunits CaVα2δ-1 and CaVβ1b. Mean I/V curves (right panel) for CaV1.2 WT (filled circle, n = 9) and CaV1.2-BBS (open circle, n = 18) co-expressed with auxiliary subunits CaVα2δ-1 and CaVβ1b. c Confocal images showing plasma membrane expression of CaV1.2-BBS in tsA cells stained with α-bungarotoxin (BTX)-AF488 (top panels). CaV1.2-BBS was co-expressed with CaVα2δ-1 (left, no β) and either CaVβ1b (center) or CaVβ2a (right). Cells were incubated at 17 °C with BTX-AF488 for 30 min and fixed. The cells were then permeabilized and stained with a rabbit anti-CaV1.2 Ab and secondary Ab anti-rabbit AF594 (bottom panels). Scale 20 µm. d Average CaV1.2-BBS surface expression co-transfected with CaVα2δ-1 and either CaVβ1b (black bar), or CaVβ2a (open bar), or empty vector (gray bar). Bars are mean (± SEM) normalized to CaVβ1b mean. ***p < 0.001, n = 14; $$$p < 0.001, n = 5; paired t-test, n numbers correspond to independent experiments

We subsequently checked the cell surface expression of CaV1.2-BBS and compared the effect of co-expressing different types of auxiliary CaVβ subunits. Three days after transfection, tsA-201 cells were live-labelled with α-BTX-488 for 30 min at 17 °C, fixed and the fluorescence was quantified (Fig. 1c and d). We found that the co-expression of CaVβ1b induced a 60% increase in CaV1.2-BBS surface expression compared with no CaVβ. Additionally, although the co-expression of CaVβ2a also increased CaV1.2-BBS cell surface expression, its effect was not as marked as CaVβ1b since only a 30% increase of fluorescence was recorded (Fig. 1c and d). This result is in good agreement with a study showing differential effects of CaVβ subunits on CaV1.2-generated current densities, although it is important to note that interpretations of electrophysiological measurements can be confounded by effects on channel biophysics [17].

We then aimed to gain insight into the CaVβ subunit-dependent mechanism(s) responsible for the effects on CaV1.2 surface expression. Plasma membrane expression of CaV1.2 results from the balance between the incorporation of newly synthetized CaV1.2 from the ER, recycled CaV1.2 from endosomal compartments and the removal of channels from the plasma membrane by endocytosis [18]. We first monitored the impact of CaVβ subunits on CaV1.2 endocytosis by comparing the rate of internalization of CaV1.2-BBS (Fig. 2). We showed that CaV1.2-BBS, either co-expressed with CaVβ1b or CaVβ2a, exhibited similar kinetics of endocytosis with a time constant of ~ 6 min (Fig. 2b). This is in line with previous studies on N-type calcium channels [19, 20] and measurements on cardiac cell lines [21]. We note that when CaVβ subunits are not co-expressed, no reduction of CaV1.2-BBS fluorescence is detected over the duration of BTX incubation (after 20 min, CaV1.2-BBS fluorescence represented 100 ± 12% of the initial fluorescence, n = 3), suggesting that CaVβ subunits promote CaV1.2 endocytosis. This conclusion is different from that of a recent study showing that stabilizing the CaV1.2–CaVβ2a interaction via the creation of a concatemer increases the retention time of CaV1.2 at the plasma membrane in HEK-293 and HLA-1 cells [12]. However, in our experimental conditions, the starting level of CaV1.2-BBS fluorescence without CaVβ subunit is very low, close to the detection limit, and we cannot exclude that some endocytosis of channels may take place even in the absence of CaVβ. It was previously shown that CaV1.2 internalization is dynamin-dependent [21]. We took advantage of the dominant negative effect of the dynamin mutant K44E [16] to show that CaV1.2 internalization depends on dynamin, regardless of co-expressed CaVβ subtype (Fig. 2c and d).

Fig. 2.

CaV1.2 endocytosis is dynamin-dependent and CaVβ subtype-independent. a Representative confocal images of tsA-201 cells expressing CaV1.2-BBS and labelled with BTX-AF488 (top panels). CaV1.2-BBS was co-expressed with CaVα2δ-1 and CaVβ1b. Cells were incubated at 17 °C with BTX-AF488 for 30 min and then fixed at different time point after incubation at 37 °C, from zero (T0) to 20 min (T20). The cells were then permeabilized and stained with a rabbit anti-CaV1.2 Ab and a secondary Ab anti-rabbit AF594 (bottom panels). Scale bar 20 µm. b Time course of endocytosis of cell surface CaV1.2-BBS co-expressed with CaVα2δ-1 and either CaVβ1b (filled circle) or CaVβ2a (open circle). The results are shown as the mean ± SEM. The n numbers correspond to independent experiments (average fluorescence from at least 25 cells per time point). The data were fitted with single exponentials. The time constants of the fits were 5.6 ± 0.2 min for CaVβ1b and 7.1 ± 0.2 min for CaVβ2a, respectively. c and d Effect of dominant negative dynamin Dyn K44E on CaV1.2 endocytosis. Cells were transfected with CaV1.2-BBS, CaVα2δ-1 and either CaVβ1b (c) or CaVβ2a (d) together with either empty pcDNA3.1 vector (filled symbols) or Dyn K44E (DDN, open symbols). Cells were incubated at 17 °C with BTX-AF488 for 30 min and then fixed at time point T0 and T20 after incubation at 37 °C. Cells were subjected to immunocytochemistry as described in a. BTX-AF488 fluorescence was normalized to the mean fluorescence at T0 for each condition. The results are shown as the mean ± SEM. The n numbers correspond to independent experiments (average fluorescence from at least 25 cells per time point). $$p < 0.01 Control T10 vs Control T0; *p < 0.05 DDN T10 vs Control T10, unpaired t-test

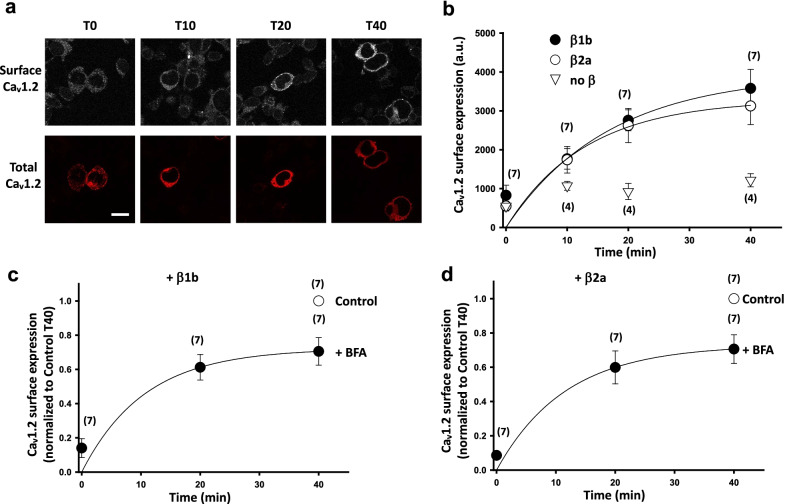

Next, we examined the effect of CaVβ subunits on net forward trafficking by monitoring the insertion of CaV1.2-BBS into the plasma membrane as a function of time (Fig. 3a and b). In the no CaVβ condition, CaV1.2-BBS surface expression doubled after 10 min and stayed stable during the next 40 min. However, when CaVβ subunits were co-expressed, we recorded an increase of CaV1.2-BBS surface expression that reached a plateau after 40 min. The increases were comparable for both CaVβ subunits and represented ~ 5 times the starting amount of CaV1.2-BBS surface expression. This is surprising, given that the steady state level of CaV1.2 is higher in the presence of the CaVβ1b isoform (see below).

Fig. 3.

CaV1.2 forward trafficking and recycling are not CaVβ-subtype dependent. a Confocal images of tsA-201 cells expressing CaV1.2-BBS and labelled with BTX-AF488 (top panels). CaV1.2-BBS was co-expressed with CaVα2δ-1 and CaVβ1b. Cells were incubated at 17 °C with untagged BTX for 30 min and then incubated at 37 °C with BTX-AF488. The cells were fixed at different time point after incubation at 37 °C, from zero (T0) to 40 min (T40). The cells were then permeabilized and stained with a rabbit anti-CaV1.2 Ab and a secondary Ab anti-rabbit AF594 (bottom panels). Scale bar 20 µm. b Time course of insertion of CaV1.2-BBS at the cell surface when co-expressed with CaVα2δ-1 and either CaVβ1b (filled circle), CaVβ2a (open circle) or empty vector (open triangle). The results are shown as the mean ± SEM (n numbers correspond to independent experiments). Data were fitted with single exponentials. The time constants of the fits were 16.8 ± 12.6 min and 13.0 ± 14.2 min for CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a (n = 7), respectively. c and d Effect of Brefeldin A (BFA) treatment on CaV1.2 forward trafficking. tsA-201 cells were co-transfected with CaV1.2-BBS, CaVα2δ-1 and either CaVβ1b (c) or CaVβ2a (d). Cells were treated with BFA for 4 h before undergoing the forward trafficking protocol described in a. BTX-AF488 fluorescence was normalized to the mean fluorescence at T40 for the control condition (open circle). The results are shown as the mean ± SEM. The n numbers correspond to independent experiments (average fluorescence from at least 25 cells per time point). The data were compared using an unpaired t-test. The data were fitted with single exponentials. The time constants of the fits were 10.6 ± 6.6 min and 11.6 ± 8.1 min for CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a (n = 7), respectively

Finally, we used BFA to disrupt the Golgi apparatus and prevent the transfer of newly synthesized channels from the ER to the plasma membrane (Fig. 3c and d). Using this strategy, we were able to estimate that 70% of the surface CaV1.2-BBS originated from a recycling pathway [21] and we could also attribute 30% to a forward trafficking process. These contributions remained identical irrespective of whether CaV1.2-BBS was co-expressed with CaVβ1b or CaVβ2a subunits. Interestingly, the contributions recycling/forward trafficking for CaV2.2 cell surface expression were reported to be closer to 50% [19, 20], although it is important to highlight the fact that these studies were performed in a neuronal cell line and that further investigations would be needed to rule out a cell-dependent effect.

Altogether, we showed that the CaVβ subunit subtype dependent effect on CaV1.2 surface expression was not associated with any modifications of the kinetics for forward trafficking, endocytosis and recycling. These results suggest that the level of CaV1.2 (available in the ER to be trafficked to the plasma membrane) is differentially increased in the presence of different CaVβ subunits. Such a mechanism is supported by the conclusions of a previous study from our group that showed that CaVβ subunits protect CaV1.2 from ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome [9]. If so, then the fact that the observed effects were greater with CaVβ1b than with CaVβ2a suggests the possibility that a difference in the amount of CaV1.2 in the ER could be due to a differential ability of the two CaVβ subunits to protect CaV1.2 from degradation. This could potentially be due to the selective palmitoylation and membrane anchoring of CaVβ2a compared to the pure cytoplasmic expression of CaVβ1b which may have better access to the pore forming subunit in the ER. Alternatively, it is possible that the latter may be expressed at higher levels than the former and thus more effective in protecting the channel from degradation. We also consider the possibility that the protective effects of the CaVβ subunit may not be dependent on a physical interaction with the CaV1.2, but instead act by regulating calcium channel expression at the transcriptional or translational level. For example, for CaV3 calcium channels, coexpression of ancillary subunits promotes current densities despite an absence of a physical interaction [22]. On the other hand, mutation of CaV1.2 residue W440 which prevents the physical association with the CaVβ subunit leads to compromised membrane expression of the channel [9, 23], thus arguing against a diffuse effect on CaV1.2 protein expression. Overall, our data are consistent with a mechanism by which CaVβ subunits are more important for regulating the levels of CaV1.2 channels at the level of the ER, rather than directly altering the forward and reverse plasma membrane trafficking of the channel complexes. This does not negate the possibility that these subunits may be involved in modulating the targeting of CaV1.2 channels to specific sub-loci within the plasma membrane.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lina Chen for technical support.

Author contributions

LF, SG and ES collected data. LF wrote the manuscript. GWZ edited the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant to GWZ from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. GWZ holds a Canada Research Chair.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials will be made available based on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sydney D. Guderyan and Ethan J. Smith contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Catterall WA, Leal K, Nanou E. Calcium channels and short-term synaptic plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10742–10749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.411645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheeler DG, et al. Ca(V)1 and Ca(V)2 channels engage distinct modes of Ca(2+) signaling to control CREB-dependent gene expression. Cell. 2012;149:1112–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Lenaeus MJ, Gamal El-Din TM. Structure and pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;60:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A, Dolphin AC. The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of voltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:821–870. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermair GJ, Szabo Z, Bourinet E, Flucher BE. Differential targeting of the L-type Ca2+ channel alpha 1C (CaV1.2) to synaptic and extrasynaptic compartments in hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2109–2122. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Biase V, et al. Surface traffic of dendritic CaV1.2 calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13682–13694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2300-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buraei Z, Yang J. The ß subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolphin AC. Calcium channel auxiliary α2δ and β subunits: trafficking and one step beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:542–555. doi: 10.1038/nrn3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altier C, et al. The Cavβ subunit prevents RFP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:173–180. doi: 10.1038/nn.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meissner M, et al. Moderate calcium channel dysfunction in adult mice with inducible cardiomyocyte-specific excision of the cacnb2 gene. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15875–15882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, et al. Cardiac CaV1.2 channels require β subunits for β-adrenergic-mediated modulation but not trafficking. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:647–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI123878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad R, Kortzak D, Guzman GA, Miranda-Laferte E, Hidalgo P. CaVβ controls the endocytic turnover of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channel. Traffic. 2021;22:180–193. doi: 10.1111/tra.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien AJ, Carr KM, Shirokov RE, Rios E, Hosey MM. Identification of palmitoylation sites within the L-type calcium channel beta2a subunit and effects on channel function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26465–26468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin N, et al. Unique regulatory properties of the type 2a Ca2+ channel beta subunit caused by palmitoylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4690–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang FX, Gadotti VM, Souza IA, Chen L, Zamponi GW. BK potassium channels suppress Cavα2δ subunit function to reduce inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Cell Rep. 2018;22:1956–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herskovits JS, Burgess CC, Obar RA, Vallee RB. Effects of mutant rat dynamin on endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:565–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasuda T, et al. Auxiliary subunit regulation of high-voltage activated calcium channels expressed in mammalian cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferron L, Koshti S, Zamponi GW. The life cycle of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in neurons: an update on the trafficking of neuronal calcium channels. Neuronal Signal. 2021;5:NS20200095. doi: 10.1042/NS20200095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferron L, et al. FMRP regulates presynaptic localization of neuronal voltage gated calcium channels. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;138:104779. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macabuag N, Dolphin AC. Alternative splicing in Ca(V)2.2 regulates neuronal trafficking via adaptor protein complex-1 adaptor protein motifs. J Neurosci. 2015;35:14636–14652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3034-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conrad R, et al. Rapid turnover of the cardiac L-type Ca. iScience. 2018;7:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubel SJ, et al. Plasma membrane expression of T-type calcium channel alpha(1) subunits is modulated by high voltage-activated auxiliary subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29263–29269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obermair GJ, et al. Reciprocal interactions regulate targeting of calcium channel beta subunits and membrane expression of alpha1 subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5776–5791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials will be made available based on reasonable request.