Abstract

Autonomy – acting volitionally with a sense of choice – is a crucial right for children. Given parents’ pivotal position in their child’s autonomy development, we examined how parental autonomy support and children’s need for autonomy were negotiated and manifested in the context of children’s independent mobility – children’s ability to play, walk or cycle unsupervised. We interviewed 105 Canadian children between 10 and 13-years-old and their parents (n = 135) to examine child-parents’ negotiation patterns as to children’s independent mobility. Four patterns emerged, varying on parental autonomy support and children’s need/motivation for independent mobility: (1) child/parent dyad wants to increase independent mobility; (2) child only wants to increase independent mobility while parents do not; (3) child does not want to increase independent mobility while parents do; and (4) child/parent dyad does not want to increase independent mobility. Findings illuminate the importance of recognizing children as active and capable agents of change.

Keywords: parenting styles, self-confidence, autonomy granting, parent-adolescent relationships

Background

Children’s Autonomy and Parenting in the 21st Century

Autonomy is a critical part of children’s development, particularly in early adolescence where children are eager to gain a sense of the self as a separate, self-governing individual, detached from their parents (Berk, 2013; Spear & Kulbok, 2004). Becoming autonomous brings invaluable developmental, psychological and emotional benefits to children as they can make decisions independently and freely, exercising their own evaluative discretions and rational capacities, and learn from their own mistakes (Archard, 2015; Haworth, 1984; Kouros, Pruitt, Ekas, Kiriaki & Sunderland., 2017). While society and institutions (e.g. educational system), community, extended families and friends bear, in part, the common duty toward a child’s autonomy development, it is unquestionably one of parents’ primary responsibilities (Betzler, 2015; United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989). The benefits of supporting autonomy development are clear as the literature consistently report positive association between parental autonomy support and children’s mental and physical health (Hwang & Jung, 2021; Reed et al., 2016).

Intensive parenting describes a child-centred and expert-guided parenting practice that makes extensive demands on parents’ time and resources invested in their children’s lives (Hays, 1996). This approach has intensified in the 21st Century and is based on parents’ good intention to protect their children from harm and promote their success (Ulferts, 2020). Its proliferation across many countries is apparent by its many colloquial names, depending on the local cultures, such as helicopter parenting, tiger parenting or snowplough parenting (Burns & Gottschalk, 2019). Literature suggests that intensive parenting is a by-product of over-emphasizing parents’ roles for child outcomes (Wall, 2010); increasing societal inequalities fuelling parents’ fear for their children’s future and driving them to curate their children’s lives to enhance achievement (Doepke et al., 2019); and constantly accessible media that sensationalize provocative topics such as child abduction and molestation, increasing parents’ fears for children’s safety (Doepke & Zilibotti, 2014; Ulferts, 2020).

There is some evidence that intensive parenting is positively related to children’s physical, cognitive and social health outcomes such as gross motor skills (Schiffrin et al., 2015; Yerkes et al., 2019), cognitive and language skills (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013), academic achievement (Fan & Chen, 2001), and improved social and emotional outcomes with fewer behaviour problems (Nokali et al., 2010). However, if excessive, it could also have detrimental effects on children’s development and well-being (Schiffrin et al., 2015). Literature documented that adolescents and young adults whose parents adopted an intensive parenting approach experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression, and lower levels of coping skills (Schiffrin et al., 2014), internal locus of control (Kwon et al., 2016) and academic achievement (Kim et al., 2013). This may be because decisions made in intensive parenting can be based on fears and anxiety, and manifested in excessive control, problem-solving for the child, over-scheduling and surveillance (Cline & Fay, 2006; Janssen, 2015; Schiffrin et al., 2015).

Previous research highlights children’s capability in exercising autonomy. For example, a Dutch study found that children were able to balance between following authority (e.g. parenting rules) and maintaining their own autonomy by adopting different negotiation strategies with their parents (Visser, 2019). Children in this study gauged the situation and the relationship with their parents to select the negotiation strategy that would best suit their goals at a given time (e.g. spending time with friends that parents do not approve of). Yet, the intensive parenting discourse positions children as adults-in-the-making: naïve, and incapable of making good judgement and taking responsibility for themselves. The focus is on parenting norms and societal expectations, rather than each child’s competence, developmental and psychological needs (Bandura, 1989; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Accordingly, intensive parenting tends to discount children’s autonomy – to act volitionally, with a sense of choice (Deci & Ryan, 2008) – and they are viewed as passive. This perception of children being vulnerable and lacking agency can negatively influence their autonomy development (Schiffrin et al., 2014, 2015).

Parental Autonomy Support: Conceptual Framework

Skinner et al.’s (2005) core dimensions of parenting and self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, 2000) provide a conceptual framework from which to consider parental autonomy support. Skinner et al. (2005) posit three core dimensions of parenting: parental warmth/rejection, parental autonomy support/coercion and parental structure/chaos. Each dimension exists on a continuum, acknowledging the organic and fluid nature of parenting which shifts in various interconnected socio-ecological contexts and in relation to children’s characteristics and maturity. Parental warmth, the most basic and essential parenting quality, refers to the expression of affection, love, appreciation and regard. Parental warmth is linked to children’s mental health, behavioural problem and social functioning (Waller et al., 2013). Parental autonomy support relates to the extent to which parents allow children freedom of choice, as well as to actively discover, explore and articulate their opinions and choices. It is positively associated with children’s academic achievement, psychosocial functioning, psychological health among others (Vasquez et al., 2015). Finally, parental structure refers to the extent to which parents provide clear and consistent guidelines. Having well-defined and reasonable expectations is positively associated with children’s social and affective skills, and the fulfilment of children’s need for autonomy as well as reduced likelihood of children engaging in anti-social behaviours (Costa, Sireno, Larcan, & Cuzzocrea, 2018).

Skinner et al.’s (2005) three dimensions of parenting are often explored in conjunction with SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000). SDT examines the extent to which an individual’s behaviour is self-motivated and self-determined. This theory posits three basic and universal psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy and competence, which are the basis for self-motivation and self-determination. The continuum of motivation includes three distinctive forms of motivations: amotivation, controlled motivation and autonomous motivation. Amotivation is a state of lacking the motivation to act such that people either do not act at all or act without intent. Controlled motivation is where the source of motivation derives from outside such as to receive rewards or avoid punishment. At the other extremity of the continuum is autonomous motivation (e.g. self-determined), which is more likely to produce positive and lasting outcomes than controlled motivation (Hagger et al., 2014).

SDT’s basic and universal psychological needs relate to Skinner et al.’s (2005) core dimensions of parenting. Children’s need for relatedness connects to Skinner et al.’s (2005) dimension of parental warmth; need for autonomy to parental autonomy support; and, need for competence to parental structure (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ulferts, 2020). Empirically, the fulfilment of these needs is associated with multiple beneficial outcomes in children’s development and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ng et al., 2012).

Independent Mobility in the Context of Autonomy Development

Children’s independent mobility – the ability of children to play, walk or cycle without adult supervision (Hillman et al., 1990) – can offer a viable opportunity for children to develop and exercise autonomy (Herrador-Colmenero, Villa-Gonzalez, & Chillon, 2017; Lu, McKyer, Lee, Goodson, & Goodson, 2015). In literature, it is documented that children who had greater independent mobility (e.g. to commute to school) exercised greater autonomy than those with lesser independent mobility granted (Herrador-Colmenero et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2015). However, children’s independent mobility has significantly declined in the past three decades (Schoeppe et al., 2016), a trend that is in concert with parents assuming greater power in managing children’s time and activities (Chudacoff, 2007). The downward trend in children’s independent mobility is heavily influenced by parents’ sense of safety and their perception of their child’s maturity and competence (Lee et al., 2015). Parents who perceived their children being more capable and mature tend to allow their children greater independent mobility (Rodriguez-Ayllón et al., 2020).

Independent mobility represents a fruitful area of investigation of children’s autonomy development, since it directly involves children negotiating their independence with their parents to exercise their autonomy. While many studies examine child/parent relationships (Borawski et al., 2003; Fan & Chen, 2001; Pallini et al., 2014), in-depth understanding of how children and parents negotiate children’s autonomy in their everyday lives remains scarce. To address this gap, the current paper aimed to better understand children and their parents’ collective yet contested multiple realities with regards to negotiating independent mobility – balancing children’s need for autonomy and parents’ autonomy support. We sought to describe the negotiation patterns that children aged 10–13 years and their parents used in the context of autonomy development – that is expanding children’s independent mobility.

Methods

State of Play: Socio-Ecological Perspectives on Children’s Outdoor Play

The current analysis used a subset of the qualitative data collected as part of a larger study, the State of Play: Socio-Ecological Perspectives on Children’s Outdoor Play – methodology described elsewhere (Han et al., 2018). This mixed-methods study examined children and their parents’ perspectives towards their neighbourhood in the context of children’s outdoor play premised on the socio-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). After obtaining ethics approval from the University of British Columbia and Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia Research Ethics Board, children 10–13-years-old and their parents from three neighbourhoods in the Metro Vancouver Regional District, were recruited and interviewed. Children in our study represent the age range associated with expansion of independent mobility (Moore, 1986). Increasing age and maturity levels have both been linked to more independent mobility (Lee et al., 2015) and, by age 11, most children are allowed to exercise minimal independent mobility (e.g. to cross main roads) which expands further by age 15 (Shaw et al., 2015). In the current paper, we describe the methods pertinent to the current analysis.

Data

To gain a deeper understanding of children’s realities, children participated in go-along interviews. The go-along interviews occurred during a walk guided by participants in their neighbourhood, an environment where they would feel most familiar and comfortable (Carpiano, 2009). To better understand how children’s need for autonomy and parental autonomy support influence children’s sense of autonomy in negotiating independent mobility with their parents, it is imperative to consider both the child and their parent(s) as a dyad within their familial context. In particular, children’s own accounts of their realities must be included to recognize their position and participation as active agents in the decisions made about their independent mobility (Hilppö et al., 2016). Hence, in the context of our study, we invited children to lead their interview by guiding us to places they liked or disliked, and routes they usually used to get to different places in their neighbourhood that were important to them. We used conventional qualitative interview methods for parents (Mason, 2011), following a semi-structured interview guide that included open-ended questions and prompts to help elicit and complete participants’ descriptions of their perceptions. In the current paper, we focused the analyses on the parts of the interviews that described the ways children aged 10–13 years and their parents negotiated independent mobility in the context of children’s autonomy development.

Analytical Methods

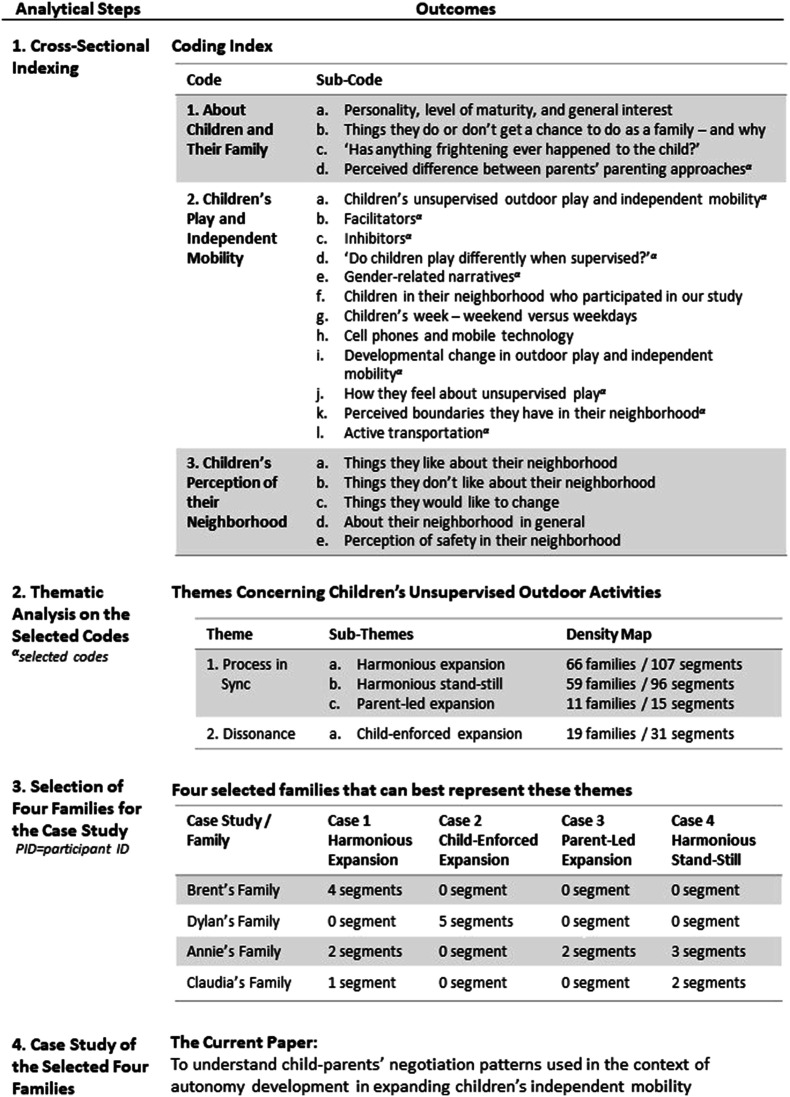

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and transcripts were reviewed by a researcher for accuracy and de-identification. Data analyses for the current paper involved four analytical steps which are described in Figure 1. First, the de-identified transcripts were read and reviewed multiple times by a team of researchers to build a codebook. This involved an iterative process of cross-sectional indexing (Mason, 2011). The primary purpose of cross-sectional indexing is to establish a systematic way to put given narrative into one or more codes and sub-codes per emergent themes that the researchers can later explore for analyses (Mason, 2011, p. 165). This method enabled to assign diverse (and seemingly unconnected) narratives into a set of pre-determined codes. For instance, some narratives in our study were assigned into multiple codes and/or sub-codes, as a given narrative can touch on several themes (see Figure 1, step 1).

Figure 1.

Analytical steps to the current analysis.

The final coding was developed by five researchers (2 principal investigators, 1 research coordinator and 2 graduate students). Several transcripts were initially read by all five researchers and a review of the discrepancies was used to refine the coding. This process was repeated until the inter-rater discrepancies were minimal and no new codes emerged. A total of five group meetings were held until the group reach consensus on the codebook. Researchers used the finalized codebook to code the remaining transcripts. The coding was entered in the NVivo 12TM software (QSR International PTY Ltd, Melbourne, Australia).

The second step in the analyses consisted of selecting specific codes from the master codebook deemed relevant to the topic of the current paper – how children aged 10–13 years and their parents negotiated independent mobility. All the narratives included in the second step were re-read using the interpretive lens to construe the data beyond its literal meanings (Green & Thorogood, 2009). We used the thematic analysis with an inductive approach by reading the data multiple times without a pre-set theoretical underpinning (Braun & Clarke, 2008), which yielded four patterns of parent–child negotiation regarding independent mobility.

The third step in the analyses consisted of identifying four families from the 105 families which illustrated the four patterns of parent–child negotiation and provided the nuanced familial context. The selection criteria for the four families were based on the following factors: inclusion of more than one segment in each of the themes, the quality of segments to provide content breadth, and added value from the parent interview(s) (e.g. how parent’s perspectives concur with or contest against their child’s interview).

Finally, for the current paper, we reviewed the entire interviews of both the child and parent(s) and considered each family as the unit of the analysis. Case study method was specifically chosen for the final analysis as it allowed the investigators to explore a real-life, contemporary bounded system (e.g. by time and place) to describe a unique case (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 96). More specifically, we are presenting multiple cases (4 patterns of negotiations), where we viewed each parent–child dyad as a real-life and bounded situation. This method enabled us to provide detailed description of each case, an approach known as a within-case analysis, followed by providing interpretation by merging and comparing between the cases, a process called a cross-case analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Analytical Frameworks

The final iteration of our analysis was informed by three overarching frameworks. The socio-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1986) underpinned our analyses and interpretation, acknowledging the factors that could influence the ways children and their parents negotiated independent mobility at different socio-ecological levels. For instance, we sought to recognize the micro-level factors – the interactive relationship between child and parents – to the macro-level factors such as societal norms related to children’s independent mobility, in the analyses. Secondly, we recognized parent–child negotiation for independent mobility as a gendered practice within societal expectations and idealized cultural practices around gender (Ridgeway, 2009). To that, we adopted the social construction of gender framework (Lindsey, 2016) to grasp how children and their parents’ negotiations of independent mobility were influenced by the gender of the child and the parent(s). Thirdly, we adopted parental autonomy support, one of the three core dimensions of parenting (Skinner et al., 2005) and integrated it into SDT’s three basic universal psychological needs (i.e. needs for relatedness, autonomy and competence). We paid particular attention to the discourse children used to frame their storytelling about the ways they negotiated their independent mobility for a better understanding of their underlying sense of autonomy and competence. We also acknowledged that children’s views and experiences are different than adults (Christensen & James, 2017; Pearce et al., 2009), that while both children’s and parents’ narratives were considered, we privileged children’s voices.

Results

One hundred and five children between 10 and 13-years-old and their parents (n = 135) were recruited and interviewed (see Table 1). These families resided in one of the three neighbourhoods targeted by the main study that included one urban neighbourhood (N = 35) and two sub-urban neighbourhoods (n=70). The analyses uncovered four patterns of parent–child negotiation for independent mobility: (1) harmonious expansion where both the child and his/her parents want to increase independent mobility, and parents support their child; (2) child-enforced expansion where the child wants to increase independent mobility but his/her parents do not, and do not support their child; (3) parent-led expansion where the child does not want to increase independent mobility while his/her parents do, and parents support independent mobility; and (4) harmonious stand-still where both the child and his/her parents want independent mobility to remain static. As aforementioned, we selected four families that best represented these patterns for a deeper understanding.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics – in general and case study participants.

| Child Demographics (n = 105) | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brent | Dylan | Annie | Claudia | |||

| Age | 10 | 26 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| 11 | 28 | |||||

| 12 | 26 | |||||

| 13 | 25 | |||||

| Gender | Male | 51 | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Female | 53 | |||||

| Other (Genderqueer) | 1 | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 69 | Asian | White | White | Asian |

| Asian | 13 | |||||

| Other | 23 | |||||

| Granted independent mobility by parents a | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 2 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | 8 | |||||

| 4 | 15 | |||||

| 5 | 31 | |||||

| 6 | 49 | |||||

a1 = My child is not allowed out alone, 2 = my child is allowed out within my yard/driveway, 3 = my child is allowed out within my street, 4 = my child is allowed out within 2–3 streets from my home, 5 = my child is allowed out within a 15-min walk from home, 6 = my child is allowed out more than a 15-min walk from home.

bMissing “age” information for one parent participant.

Four Cases of Parent–Child Negotiation for Independent Mobility

Case 1. Harmonious Expansion – Brent’s Family

Brent was a 13-year-old boy who has lived in the same house in an urban neighbourhood with his parents and a younger brother, since he was 7 years old. Brent described his independent mobility range as extending to the US border (approximately 42 km away). When asked if he would let his parents know if he were to go to the US border, Brent clarified that, ‘I probably wouldn’t actually do that [going down to the US border] but just as an example (…) I would always lock the doors and make sure like no one can get in and make sure I have my phone and my wallet with me but I’d probably let them know in the middle [laughs]’. Brent was confident that he knew his neighbourhood enough that he ‘can recognize where I am and normally if I know how to get to (name of a public transit station), I can get home’. Brent’s claim was supported by both of his parents, Bonnie and Bryan. Bryan agreed that Brent’s boundaries were not ‘really a function of distance. It’s more sort of ‘are we confident he’s actually going to get where he’s going’. Evident throughout their interviews was mutual trust. When asked what Brent was allowed to do unsupervised, Bonnie clarified, ‘Brent could do whatever he likes, basically (…) he’s got a [public transit card], he has his own money, so he can go see a movie if he wants’.

Bryan and Bonnie agreed in their parenting approach, perhaps resulting from similar childhood experiences, which Bonnie recalled as being ‘left on my own device’. She mentioned that, ‘it was a pretty good childhood and we want basically the same kind of thing for our kids to be able to just go and do stuff on their own and not need to be totally structured’. She stressed that she wanted her children to ‘have time to just be kids’. Bryan further elaborated that, ‘we don’t want to be helicopter parents and be supervising all the time (…) philosophically I think it’s important for them to develop the responsibility on their own and self-reliance on their own’.

During the interview, Brent communicated a number of times how he appreciated his parents’ trust and did not want to compromise the existing harmony. He recalled a previous incident:

Brent: Well my parents kind of trust me more as I get older. They just they’re just really trusting because I’ve done some very unsavoury things in the past, but my parents think I’ve corrected that so they’re a lot more trusting, and because I know self-defence they’re not scared of me going out somewhere by myself.

With increasing age and confidence, Brent claimed that he knew how to ‘handle himself’ most of the time. Yet, he did not hesitate to ask for his parents’ help and guidance when needed. When Brent started taking public transit to his new school, he found the situation ‘unsettling’. However, according to Brent, his father ‘let him ease into it until I felt comfortable’.

Case 2. Child-Enforced Expansion – Dylan’s Family

Dylan was an 11-year-old boy who had always lived in the same urban neighbourhood. Dylan was an only-child and according to his mother, Dolores, he was a ‘big and strong kid’ who ‘really wants privacy’. He was ‘not a super active or sporty but competitive, he likes to win at things’ and ‘he loves his friends and his social network of friends is really important to him’. According to Dylan, he enjoyed a large independent mobility range, as since he ‘was nine-ish, that was when I was starting to be allowed to go over to friends’ house by myself’ and now had ‘complete freedom’.

However, Dylan’s perceptions differed from those of his mother. When asked about being allowed to take the public transit on his own, Dylan explained, ‘I don’t know if I’m allowed to this day. I just did it and I just don’t tell my parents. If you don’t know, don’t tell’. He interpreted Dolores’ reluctance to let him have more freedom because ‘she just doesn’t really trust me too much’. He stressed numerous times during his interview how he felt ‘100% comfortable’ navigating by himself in his neighbourhood. Dylan further elaborated receiving conflicted messages from his parents:

Dylan: Well, the thing is my mom, there’s a wall I kind of have to stay inside of. Like there’s [major street 1] that I can’t go by myself. [Major street 1], [major street 2], [major street 3] and [major street 4] (approximately 1.3 km2). But my dad, according to him, if I can go that far and come back afterwards, he’s okay with me going there.

Dylan’s resistance to authority and rules transcended his mother’s rules. Dylan expressed his special fondness for a structure that he can climb onto at his school. He was proud of being ‘the only kid in the school who can actually climb up onto [a structure at his school] and ‘it’s the one thing I can do that nobody else can do’. He included this place as a destination in his go-along interview and provided details on how he climbed onto it without using a ladder. When asked if this was allowed by the school, he replied that ‘I’d probably be suspended and that’s why I go there on the weekends’. Dylan shared many episodes where he was breaking rules, later confirming confidentiality with the researcher: ‘you sure my parents won’t hear this? Because this is stuff that I haven’t told them’.

Dolores was mostly aware of Dylan’s mischief. She revealed that, ‘occasionally I caught him doing stuff that’s unsafe’. She also knew that ‘Dylan went with his friend on a bus all the way to a store’, an incident she ‘didn’t know about until afterwards [and] probably would never have approved’. Dolores seemed to have little trust in Dylan, which had led her to spy on Dylan on a few different occasions. She recalled the time when Dylan ‘asked if he could start walking to school by himself’, a process that ‘was led by Dylan last year’:

Dolores: The first couple of times I think I let him go three blocks ahead and I was like peaking to make sure that he wasn’t gonna… It’s funny because actually one of the first times he didn’t go straight to school he went to the corner store and bought a can of pop. And I don’t let him drink pop (…) so I think I said, ‘oh I have to walk you to school now for another month’.

Notably, Dolores grew up in a small town in a big family on a big property ‘in the middle of nowhere’ and walked to school 1 km unsupervised from age five. She reminisced being ‘allowed to run around free because it was the seventies’. Dolores communicated her concerns around ‘some kids of Dylan’s age just totally over scheduled and aren’t really unsupervised very much outside the house’. This was in sharp contrast to Dylan’s perspective: ‘if it was up to mom, I’d be involved in like two things of swimming lessons, one thing of skating, one thing of fencing, basically I’d have no free time’. Throughout the interview, Dylan expressed his longing for more freedom. When asked what ‘freedom’ meant to him, Dylan replied: ‘freedom means to me, getting a choice to do what you want instead of somebody choosing for you’. He further expressed his preference being unsupervised:

Dylan: If anything, I feel better when I’m not with an adult because I kind of have my own freedom whenever I’m by myself. When I’m with a parent it’s always really, it’s like there are walls of what I can and what I can’t do. Without my parents? Boom bust down those walls!’

Case 3. Parent-Led Expansion – Annie’s Family

Annie’s family lived in their sub-urban neighbourhood for over 10 years. Annie was a 12-year-old girl, the youngest of Amalie and Allan’s three children, with two older brothers. Annie felt safe and extremely connected to her neighbourhood, which was exactly what Amalie was hoping for when she and Allan chose to relocate in their neighbourhood. Amalie grew up with a lot of freedom as a child; yet, she remarked that she missed social interaction growing up. Amalie’s reflection on her own childhood illuminated her preference for a closely-knit and walkable neighbourhood as she elaborated, ‘we purposely moved to a neighbourhood which would enable our kids to walk to the park with friends, or to walk into the village to do errands, and things like that’.

In realizing her vision, Amalie ‘would try and fabricate reasons to have my children to go into the village unaccompanied, starting at sort of 9-ish as a pair (…) just to give them a sense of their area’. By the time Annie turned 12, Amalie felt confident in her daughter’s ability to be more independent in their neighbourhood. She praised Annie for being ‘very functional’, ‘responsible’, ‘thoughtful’ and ‘more mature’ than her 17-year old brother, which fostered ‘this general feeling of trust about the situation’. Amalie was confident about the whereabouts of Annie when she was out unsupervised, and that Annie would never exceed the granted boundaries without communicating with her beforehand. Annie confirmed this in her interview. When asked if she had ever gone further than she was allowed to, Annie communicated her preference not exploring further at least, ‘not without my parents knowing’. and expressed her preference for being with her parents over her friends:

Annie: Normally, I don’t mind being without my parents, I mean it doesn’t scare me but if they’re like ‘would you rather go to the mall with you friends or with your parents’, I’d probably do with the parents. It just, I don’t know, I always feel safer with them.

Annie noted that her independence expanded the previous year upon receiving a cell phone when Annie started walking to school by herself or with friends since her older brother was no longer in the same school. Annie further explained:

Annie: my parents just thought it’d be better if I had a phone so when I got to school I do have Wi-Fi, so I could just text them say I’m at school. And then when I left for school I could say oh can I hang out with my friends.

Researcher: So it was your decision or your parents’ decision to get a phone?

Annie: Kind of both of our decisions, yeah.

Case 4. Harmonious Stand-Still – Claudia’s Family

Claudia, an 11-year-old girl, recently moved to a sub-urban neighbourhood with her parents, a younger brother and a family dog. Claudia was still attending the school in her old neighbourhood and mentioned that she did not have many friends in her new neighbourhood. When asked what kinds of activities she was allowed to do unsupervised, Claudia explained that ‘most of my time is supervised (…) as there’s really nothing I do unsupervised’. Claudia seemed to accept having limited independent mobility in her current neighbourhood. She described herself as an anxious person who ‘gets frightened of big crowds’. Likewise, her mother, Cindy acknowledged her own fear and anxiety that made her reluctant to let Claudia go outside on her own beyond their block. Cindy described her daughter as responsible yet still not mature enough to be outside unsupervised. Cindy’s discomfort was apparent in her narrative:

Cindy: All I allow her to go is around the block, that’s the maximum she can go. Maybe with time I’ll just increase the boundary. But right now, I’m not comfortable sending her. I mean, I know she’s responsible enough, but, I mean I’m just a little worried, that’s it.

R: And what do you worry about?

Cindy: About like, what if she doesn’t see a car or if a car hits her or, I don’t know, it’s a, it’s a safe neighbourhood so I’m not worried that someone might take her away, but I just don’t want like eve-teasing (i.e. sexual harassment) or something, like I’ve heard those kids it’s happening on [one of the major streets in her neighbourhood]. So maybe that or she has to be prepared for it, but I’m not ready yet.

Cindy’s anxiety seemed to exacerbate Claudia’s as she recalled her parents’ stories of ‘a girl waiting for her mom outside of the house and then this lady with an RV just comes around, picks her up, puts her in the RV and just drives away’ and of ‘a high schooler who jay walked across the road and got run over by a car’. Claudia shared that, ‘my parents tell me a lot of stories of children who weren’t as cautious, probably to build up my cautiousness I guess, and I do build it up’.

The family’s anxiety and Claudia’s lack of familiarity with her new neighbourhood may explain her preference for being with her parents: ‘if I was anywhere without mom, I kind of get a bit scared’. She elaborated that: ‘I really don’t want to be anywhere without them [parents] because the places that I’d like to be are in [previous neighbourhood] because I am there mostly so I can’t get there unless I have my mom and dad’. However, while she willingly accepted and stayed within her limited independent mobility range, Claudia predicted that a significant increase in her independent mobility was imminent. Her mother’s work situation made picking Claudia and her brother up after summer school challenging. Claudia seemed to be ‘okay with that actually, because I have done it with my mom before, a couple of times, so I knows how it works’ and excited about this new venture as she eagerly gave the interviewer detailed directions. Cindy also shared this sentiment and acknowledged that Claudia would soon be ready for more independence. She ‘has seen a difference in her and she will be ready by the time she will be 12. Like by knowing her as her personality goes, she’s getting there’. When asked if she was willing to give Claudia more independence based on her personality or the actual age, Cindy answered ‘age’.

Discussion

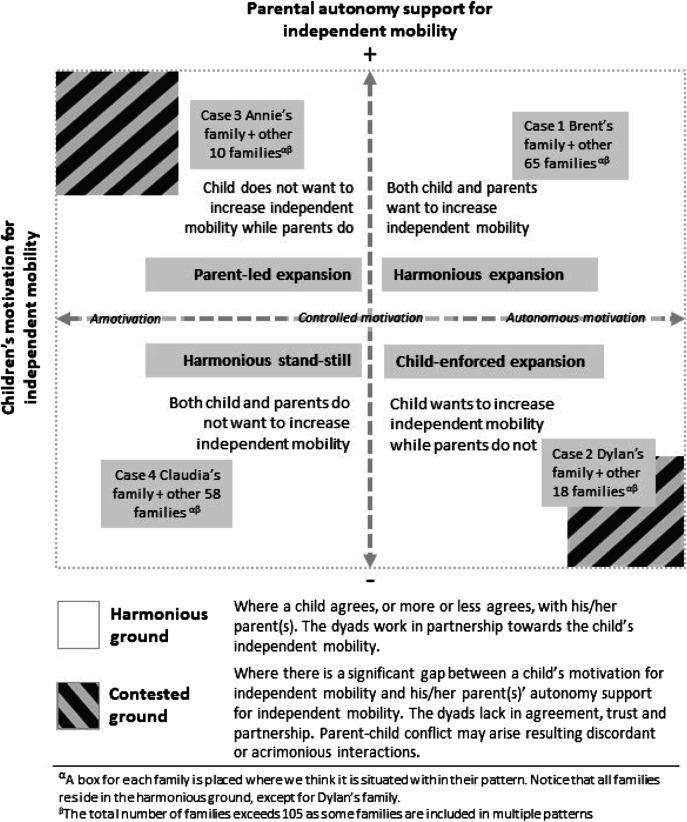

Using a case study methodology, our research provided a nuanced understanding of how four patterns of parent–child negotiation for independent mobility manifested itself in the familial context. We were able to explore how parents’ general parenting philosophy translated into (or not) actual parenting practice, and how children could exercise their agency when there was discordance between a child’s motivation for independent mobility and his/her parent(s)’ autonomy support for independent mobility. In other words, we explored parent–child dyads by positioning them in a model that is an integration of the parental autonomy support (Skinner et al., 2005) and continuum of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000) – amotivation, controlled motivation and autonomous motivation – that represents children’s motivation for independent mobility – see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Parent–child independent mobility negotiation patterns.

We rationalized that no child was entirely autonomously motivated to gain independent mobility. In other words, children will likely have an incentive for seeking independent mobility, rather than seeking independent mobility for its own sake. This would represent a mix of controlled motivation with incentive (e.g. walk to a park to play with friends) and autonomous motivation (e.g. to feel free). The extended bracket under each family’s name in the figure 2 portrays this aspect. In addition, it is important to mention that presentation of families in Figure 2 is not absolute but rather relational and based on our interpretation. It is simply our attempt to provide a visualization for clarification.

Independent mobility in harmonious ground occurred when a child received parental autonomy support that was more or less compatible with his/her motivation for independent mobility; they were harmonious and worked in partnership towards expansion. It could be initiated by either child or parents, or both and could be controlled and/or autonomously motivated. Harmonious expansion occurred when both children and parents were comfortable with expanding children’s independent mobility. Harmonious stand-still occurred when both parties were comfortable with the current level of independent mobility. This harmonious status describes an iterative process between expansion and stand-still, and sometimes temporary contraction (e.g. when moving to a new neighbourhood), that leads to eventual independence. Harmonious ground is premised on mutual agreement and trust between children and their parents. Dyads managed their differing perspectives (if any) to make collective decisions. Based on the analysis, this process is not rigid, but rather organic and the result of complex negotiation between parent–child amid other socio-ecological factors (Bhosale et al., 2017).

Parental autonomy support mattered the most when children had high motivation (autonomous or controlled) for independent mobility. For example, Brent had a high desire to expand his independent mobility, which was well supported by his parents. Comparably, Dylan who had a similar or even higher level of motivation for independent mobility, was not as supported by his parents as he may have wanted. This conflict positioned this dyad on contested ground and a lack of trust and communication between child and parents was apparent. Some children in this pattern sometimes transgressed their parents’ rules and acted alone to exercise their independent mobility. We call this process child-enforced expansion – as was the case with Dylan. Children in this pattern often communicated their need for freedom, a sentiment that seemed to stem from their perception of parents’ rigid supervision and restrictions, which sometimes extended to anyone in a position of authority. To reinstate their sense of autonomy, these children positioned and constructed themselves as sole acting agents by practising unrehearsed or prohibited behaviours, a negative way to use performative pattern (Matthews et al., 1998; Valentine, G., 1997a, 1997b). Some of the children in this pattern were aware of and used their parents’ conflicting rules to their advantage (e.g. Dylan accepting his father’s wider boundaries rather than his mother’s).

Most families in our study resided in this harmonious ground and did not exhibit the significant gap between a child’s motivation for independent mobility and his/her parent(s)’s autonomy support of independent mobility to create contested ground. For children who had less motivation for independent mobility (e.g. amotivation or heavily controlled motivation), parental autonomy support did not create too much tension even when there was a discrepancy between a child’s motivation and the parent’s desire to provide their child autonomy support. Perhaps, this is because there were no cases in our study where parents pressured independent mobility to the point that children felt uncomfortable. Simply, parents in this pattern sought and used various strategies to encourage their children to go outside and exercise more independence in their neighbourhood, without overwhelming their child. While mainly guided by their parents, children in this pattern appreciated the trust and autonomy support received from their parents – however, children did not necessarily take full advantage of the entrusted independence. Children seemed content to practise their independence on their own terms under the oversight of and scaffolded by their parents.

Overall, children in the harmonious ground who felt supported by their parents pinned their discourse in reciprocal trust between parent–child and used language of ‘we’ and ‘us’ to present the collective ownership of the decisions they made. These children positioned themselves as active agents in equal partnership in decision-making (Hilppö et al., 2016). Children used a positive performative pattern – a way to prove their competence to their parents by demonstrating competent decision-making (MacDougall et al., 2009; Valentine, 1997a). It is also noteworthy to mention that those children who believed that they had complete freedom (e.g. going to the US border), also did not take full advantage of the entrusted independence (e.g. actually going to the US border let alone without telling parents). This leads to the argument that children’s contentment is primarily based on a sense of autonomy and trust they received from their parents, which informs their perceived independent mobility rather than their actualized independent mobility (Han et al., 2020).

In contrast, the contested ground is characterized by lack of agreement, trust and partnership between parent–child. It is reasonable to believe that while these parents provided as much parental warmth (not rejection) and guidance (not chaos) as parents in the harmonious ground, there seemed to be a deficiency in supporting children’s autonomy – at least from the child’s point of view. To be more precise, there was a chasm in the level of independent mobility and autonomy children desired and the parental support they perceived. This could be detrimental as autonomy support can feed into other needs as ‘it can signal acceptance of who they are as a person (relatedness) and trust their ability to make appropriate choices (competence)’ (Ulferts, 2020, p. 14).

These findings highlight that parenting is not unidirectional. Children are not passive recipients of their parents’ warmth, support and guidance, and conflicts can arise during negotiations. A caring and trusting environment is one where both parties can comfortably and effectively communicate their wants, needs and concerns (Laursen & Collins, 2004; Visser, 2019) – without necessarily agreeing. In other words, it is critical to work towards a common goal in equal partnership. This aligns well with the three dimensions of parenting by supporting children’s psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy and competence (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ulferts, 2020). Moreover, literature points to a general parenting approach being more important to child outcomes than specific parenting actions (Smetana, 2017).

Participating parents described childhoods with plentiful freedom, yet did not necessarily parent their own child this way. Parents who were not providing active support for independent mobility tended to focus on their own comfort level and anxiety, rather than their child’s needs, consistent with characteristics of intensive parenting (Doepke et al., 2019; Schiffrin et al., 2014, 2015; Ulferts, 2020). In this anxiety-based parenting approach, parents tend to focus on their own anxiety and reference societal and cultural norms in making decisions, rather than recognizing their child as an individual.

Parents who were supportive of independent mobility acknowledged their child’s rapid transition into adolescence. They reflected back to their own childhood experiences to better understand their child’s needs. They were flexible in tailoring their guidelines based on their parental judgements as well as their child’s own assessment. This required parents’ active involvement – not as a form of intensive parenting but rather a focus on competence-based parenting with much laddering and mentorship (Heath, 2006). Even parents, who were not actively seeking opportunities for independent mobility expansion, were aware of their child’s growing needs for independence. On mutual terms, they were gradually increasing independent mobility.

Aside from the fact that most of parents who participated in our study were mothers –highlighting that the modern parenting and caregiving roles still continue to be mostly taken up by mothers – we noticed another gender disparity. Parents in our study mostly viewed girls to be more responsible and trustworthy (e.g. Amalie praising Annie being responsible and more mature than her 17-year old brother; Cindy’s trust in Claudia’s personality) than boys who were commonly described as being more of risk-takers (e.g. Dolores’ assessment of Dylan engaging in unsafe behaviour). It seemed that parents perceived boys as having more potential to ‘cause trouble’. Yet, these assessments did not result in notably higher independent mobility in girls than boys in our study.

In the children’s data, we did not observe notable gender differences with respect to patterns they characterized. Most families in our study were harmonious and were equally distributed among boys and girls. An interesting trend we observed among children who wanted more independent mobility than their parents were willing to grant, was that girls expressed yearning for more freedom as much as or more so than boys; however, this did not necessarily lead girls to use the strategy of expansion in solo (e.g. taking bus without telling their parents) more than boys – at least they did not communicate this aspect during the interview. Finally, motivation for independent mobility was higher among older children, as was parental autonomy support, regardless of gender.

Limitation

The data presented herein represent a limited view of the lived experiences and realities that families were experiencing, which were naturally disorganized, incoherent in places and did not necessarily take the form of a sequential narrative. At times, their narratives contradicted and contested both between a child and his/her parent(s) but also within their own narratives. In addition, we had limited numbers of families reflecting various household composition (e.g., split households) and family structures and dynamics (e.g. LGBTQ families). Hence, the four parent–child dyads we included in the case analysis may not be representative of the wider population, nor even of themselves. In other words, our interpretation cannot be empirically generalized to other parent–child dyads in the context of independent mobility expansion negotiation.

Conclusion

Our analysis illuminated patterns of negotiation for independent mobility among parent–child dyads, which could be relevant to other contexts involving parent–child negotiation. Our findings stress the critical importance of open communication grounded in mutual trust and recognizing children as active and capable agents. The negotiation process flourishes when it is inclusive and children and parents partner towards a common goal, where parents are positioned as supportive mentors providing guidance and laddering, rather than as gatekeepers. While parents’ level of comfort and motivation for independent mobility expansion would naturally (or inevitably) grow as their child becomes older, it is crucial to cultivate children’s healthy sense of autonomy throughout childhood to build children’s resilience and equip them to manage life’s challenges.

Acknowlegments

We thank the participating children and parents for their generosity with their time.

Author Biographies

Christina S Han is a social science researcher with over 10 years of experience in qualitative and mixed-method research and published 25 peer-refereed articles. Her current research focuses on understanding subjective realities of children’s outdoor activities and mobility in diverse contexts using qualitative data such as children’s interviews and map drawings.

Dr. Mariana Brussoni is a developmental psychologist who investigates child injury prevention and children’s outdoor risky play, focussing on the effects of play, design of outdoor play-friendly environments, parent and caregiver perceptions of risk and development of behaviour change interventions to support outdoor play.

Dr. Louise C Mâsse is a behavioural scientist with expertise in psychometrics. Her research integrates both population-based strategies (environmental and policies strategies) and behavioural strategies (individual-based psychological strategies). Her behavioural research takes a socio-ecological perspective to examine various aspects of the environment that influence children’s behaviours associated with obesity.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant #MOP-142262. Drs. Brussoni and Mâsse are supported by salary awards from the British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

ORCID iD

Mariana J Brussoni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1495-816X

References

- Archard D. (2015). Children, adults, autonomy and well-being. In Bagattini A., Macleod C. (Eds.), The nature of children’s well-being. Theory and practice (pp. 3–14). Springer. 10.1007/978-94-017-9252-3_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk L. E. (2013). Child development. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Betzler M. (2015). Enhancing the capacity for autonomy: What parents owe their children to make their lives go well. In Bagattini A., Macleod C. (Eds.), The nature of children’s well-being. Theory and practice (pp. 65–84). Springer. 10.1007/978-94-017-9252-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhosale J. Duncan S., & Schofield G. (2017). Intergenerational change in children’s independent mobility and active transport in New Zealand children and parents. Journal of Transport & Health, 7, 247-255. 10.1016/j.jth.2017.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borawski E. A., Ievers-Landis C. E., Lovegreen L. D., Trapl E. S. (2003). Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(2), 60–70. 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T., Gottschalk F. (2019). Educating 21st century children: Emotional well-being in the digital age, educational research and innovation. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano R. M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The “Go-along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15(1), 263–272. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P., James A. (2017). Research with children: Perspectives and practices (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chudacoff H. P. (2007). Children at play: An American history. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cline F., Fay J. (2006). Parenting with love and logic: Teaching children responsibility (2nd ed.). NavPress. [Google Scholar]

- Costa S, Sireno S, Larcan R, Cuzzocrea F. (2019). The six dimensions of parenting and adolescent psychological adjustment: The mediating role of psychological needs. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 60(2), 128–137. 10.1111/sjop.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W., Poth C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Deci E. L., Ryan R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life's domains. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(1), 14–23. 10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doepke M., Sorrenti G., Zilibotti F. (2019). The economics of parenting. Annual Review of Economics, 11(1), 55–84. 10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-030156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doepke M., Zilibotti F. (2014). Culture, entrepreneurship, and growth. In Aghion P., Durlauf S. (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (1st ed., pp. 1–48). Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-0-444-53538-2.00001-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Chen M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–22. 10.1023/A:1009048817385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Thorogood N. (2009). Qualitative methods for health research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger M. S., Hardcastle S. J., Chater A., Mallett C., Pal S., Chatzisarantis N. L. (2014). Autonomous and controlled motivational regulations for multiple health-related behaviors: Between- and within-participants analyses. Health Psychology & Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 565–601. 10.1080/21642850.2014.912945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Lin Y., Mâsse L. C., Brussoni M. (2020). “There’s kind of a wall I have to stay inside of”: A qualitative understanding of children’s independent mobility range, destination, time and expansion. Children, Youth and Environments, 30(2), 97–118. 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.30.2.0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. S, Mâsse L. C, Wilson A., Janssen I., Schuurman N., Brussoni M. (2018). State of play: Methodologies for investigating children’s outdoor play and independent mobility. Children, Youth and Environments, 28(2), 194. 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.28.2.0194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth L. (1984). Autonomy and utility. Ethics, 95(1), 5–19. 10.1086/292594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heath H. (2006. Sep–Oct). Parenting: A relationship-oriented and competency-based process. Child Welfare, 85(5), 749, 66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrador-Colmenero M. Villa-González E., & Chillón P. (2017). Children who commute to school unacoompanied have greater autonomy and perceptions of safety. Acta Pædiatrica, 106, 2042-2047. 10.1111/apa.14047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman M., Adams J., Whitelegg J. (1990). One false move…: A study of children's independent mobility. PSI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hilppö J. Lipponen L. Kumpulainen K., & Virlander M. (2016). Sense of agency and everyday life: Children’s perspective. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 10, 50-59. 10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W., & Jung E. (2021). Helicopter parenting versus autonomy supportive parenting? A latent class analysis of parenting among emerging adults and their psychological and relational well-being. Emerging Adulthood. 10.1177/21676968211000498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I. (2015). Hyper-parenting is negatively associated with physical activity among 7–12 year olds. Preventive Medicine, 73, 55-59. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y., Wang Y., Orozco-Lapray D., Shen Y., Murtuza M. (2013). Does ‘‘tiger parenting’’ exist? Parenting profiles of Chinese Americans and adolescent developmental outcomes. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 7–18. 10.1037/a0030612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros C. D., Pruitt M. M., Ekas N. V., Kiriaki R., Sunderland M. (2017). Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and college students’ mental health and well-being: The moderating role of sex and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 939–949. 10.1007/s10826-016-0614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon K.-A., Yoo G., Bingham G. E. (2016). Helicopter parenting in emerging adulthood: Support or barrier for Korean college students’ psychological adjustment?. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 136–145. 10.1007/s10826-015-0195-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B., Collins W. A. (Eds.), (2004). Parent-child communication during adolescence. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Tamminen KA, Clark AM, Slater L, Spence JC, Holt NL. (2015). A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children’s independent active free play. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 5. 10.1186/s12966-015-0165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey L. L. (2016). Gender roles. A sociological perspective (6th ed.). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lu W McKyer EL Lee C Ory MG Goodson P, & Wang S (2015). Children’s active commuting to school: an interplay of self-efficacy, social economic disadvantage, and environmental characteristics. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and {hysical Activity, 12, 29–14. 10.1186/s12966-015-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall C., Schiller W., Darbyshire P. (2009). What are our boundaries and where can we play? Perspectives from eight- to ten-year-old Australian metropolitan and rural children. Early Child Development and Care: Child-Adult Relationships, 179(2), 189–204. 10.1080/03004430802667021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. (2011). Qualitative researching (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H., Limb M., Percy-Smith B. (1998). Changing worlds: The microgeographies of young teenagers. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 89(2), 193–202. 10.1111/1467-9663.00018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. C. (1986). Childhood’s domain: Play and place in child development. Croom Helm. [Google Scholar]

- Ng J. Y., Ntoumanis N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani C., Deci E. L., Ryan R. M., Duda J. L., Williams G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 325–340. 10.1177/1745691612447309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nokali N. E., Bachman H. J., Votruba-Drzal E. (2010. May–Jun). Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3), 988-1005. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallini S., Baiocco R., Schneider B. H., Madigan S., Atkinson L. (2014). Early child–parent attachment and peer relations: A meta-analysis of recent research. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 118–123. 10.1037/a0035736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce A., Kirk C., Cummins S., Collins M., Elliman D., Connolly A. M., Law C. (2009). Gaining children’s perspectives: A multiple method approach to explore environmental influences on healthy eating and physical activity. Health and Place, 15(2), 614–621. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed K., Duncan J. M., Lucier-Greer M., Fixelle C., Ferraro A. J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3136–3149. 10.1007/s10826-016-0466-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway C. L. (2009). Framed before we know it: How gender shapes social relations. Gender & Society, 23(2), 145–160. 10.1177/0891243208330313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ayllón M. Derks I. P. M. van den Dries M. A. Esteban-Cornejo I. Labrecque J. A. Yang-Huang J. Raat H. Vernooij M. W. White T. Ortega F. B. Tiemeier H., & Muetzel R. L. (2020). Associations of physical activity and screen time with white matter microstructure in children from the general population. Neuroimage, 205, 116258. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin H. H., Godfrey H., Liss M., Erchull M. J. (2015). Intensive parenting: Does it have the desired impact on child outcomes? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2322–2331. 10.1007/s10826-014-0035-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin H. H., Liss M., Miles-McLean H., Geary K. A., Erchull M. J., Tashner T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548–557. 10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeppe S., Tranter P., Duncan M. J., Curtis C., Carver A., Malone K. (2016). Australian children's independent mobility levels: Secondary analyses of cross-sectional data between 1991 and 2012. Children's Geographies, 14(4), 408–421. 10.1080/14733285.2015.1082083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B., Bicket M., Elliott B., Fagan-Watson B., Mocca E., Hillman M. (2015). Children’s independent mobility: An international comparison and recommendations for action. London Policy Studies Institute. https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/7350_PSI_Report_CIM_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E., Johnson S., Snyder T. (2005). Six dimensions of parenting: A motivational model. Parenting, Science and Practice, 5(2), 175–235. 10.1207/s15327922par0502_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 19-25. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear H. J., & Kulbok P. (2004). Autonomy and Adolescence: A Concept Analysis. Public Health Nursing, 21(2), 144-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulferts H. (2020). Why parenting matters for children in the 21st century: An evidence-based framework for understanding parenting and its impact on child development. OECD Publishing. https://data.informit.org/doi/10.3316/apo.306211. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine G. (1997. a). “Oh yes I can”. “Oh no you can’t”: Children and parents’ understanding of kids’ competence to negotiate public space safely. Antipode, 29(1), 65–89. 10.1111/1467-8330.00035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine G. (1997. b). ‘My son’s a bit dizzy.’ ‘my wife’s a bit soft’: Gender, children and cultures of parenting. Gender, Place & Culture, 4(1), 37–62. 10.1080/09663699725495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez A. C., Patall E. A., Fong C. J., Corrigan A. S., Pine L. (2015). Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 605–644. 10.1007/s10648-015-9329-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visser K. (2019). ‘I didn’t listen. I continued hanging out with them; they are my friends.’ the negotiation of independent socio-spatial behavior between young people and parents living in a low-income neighborhood. Children's Geographies, 18(6), 684–698. 10.1080/14733285.2019.1688765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wall G. (2010). Mothers’ experiences with intensive parenting and brain development discourse. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33(3), 253–263. 10.1016/j.wsif.2010.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R., Gardner F., Hyde L. W. (2013). What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(4), 593–608. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisleder A, Fernald A. (2013). Talking to children matters early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science, 24(11), 2143–2152. 10.1177/0956797613488145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes M. A., Hopman M., Stok F. M., De Wit J. (2019). In the best interests of children? The paradox of intensive parenting and children’s health. Critical Public Health, 31(3), 349–360. 10.1080/09581596.2019.1690632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]