Abstract

Introduction:

Advance care planning is recommended in chronic respiratory diseases, including Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. In practice, uptake remains low due to patient, physician and system-related factors, including lack of time, training and guidance on timing, components and content of conversations. Our aim was to explore perspectives, experiences and needs to inform a framework.

Methods:

We conducted a qualitative study in western Canada, using semi-structured interviews and inductive analysis. Patient, caregiver and health care professional participants described advance care planning experiences with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis.

Results:

Twenty participants were interviewed individually: 5 patients, 5 caregivers, 5 home care and 5 acute care health care professionals. Two categories, perceptions and recommendations, were identified with themes and subthemes. Participant perceptions were insufficient information and conversations occur late. Recommendations were: have earlier conversations; have open conversations; provide detailed information; and plan for end-of-life. Patients and caregivers wanted honesty, openness and clarity. Professionals related delayed timing to poor end-of-life care and distressing deaths. Home care professionals described comfort with and an engaged approach to advance care planning. Acute care professionals perceived lack of clarity of roles and described personal, patient and caregiver distress.

Interpretation:

Analysis of diverse experiences provided further understanding of advance care planning in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Advance care planning is desired by patients and caregivers early in their illness experience. Health care professionals described a need to clarify role, scope and responsibility. Practical guidance and training must be available to care providers to improve competency and confidence in these conversations.

Keywords: advance care planning, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, qualitative research, palliative care, hospice care, end-of-life care, interview

Advance care planning (ACP) is the ongoing communication process for individuals to consider their goals and preferences for medical care, discuss them with family and health care providers, and document and review them regularly. ACP conversations are foundational to patient-centered care in life-limiting illnesses, including Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), an incurable fibrotic lung disease with a mortality of 2 to 3 years after diagnosis. 1 IPF patients and caregivers suffer a poor quality of life marked by frustration and hopelessness, often magnified at end-of-life. 2,3 Evidence suggests ACP may improve quality of care and life by eliciting and addressing what matters most to patients and families, 4 and positively affect end-of-life care. 5 Unfortunately, ACP is inconsistently implemented in IPF despite multiple stakeholder recommendations. 2,6 -11 For example, Lindell et al reported 13.7% of IPF patients received a palliative care consultation. 12 Lack of ACP discussions is a known patient-clinician communication gap in IPF. 13 Identified barriers are health care professional (HCP) reluctance, an unpredictable disease trajectory, insufficient communication training, prioritization, and patient readiness. 2,8,14

In our provincial health system, ACP includes personal directives and medical goals of care orders (GOCs). Personal directives express preferences and name an agent if there is loss of decision making capacity; GOCs encompass wishes with medical decisions and location of care, including resuscitation, transfer to hospital, and comfort care. We sought to explore perspectives of IPF patients, family caregivers, and healthcare professionals on ACP-related experiences to understand and inform an ACP framework to guide clinicians and facilitate early, meaningful conversations.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a qualitative study and used the COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline for reporting. Patients with IPF and family caregivers (PFCs) were recruited through the local Pulmonary Fibrosis Association and IPF specialists with convenience and snowball sampling. HCPs were recruited through email invitation letters to home care (HC) and acute care (AC). No incentives were provided.

Interviews

A semi-structured interview guide was developed from the literature and expert clinician input (see supplemental file), 6,15 -18 which included preferences on content, delivery format and settings for ACP conversations. Interviews were conducted after informed consent obtained by SO, research assistant trained by first author, MK. SO had no relationship to the participants or the Multidisciplinary Collaborative Interstitial Lung Disease (MDC-ILD) Clinic. PFCs were interviewed at the university (5), at home (2) or by phone (3). HCPs were interviewed in work settings.

Qualitative Analysis

Data were systematically analyzed with inductive content analysis, 19 led by CP, PhD trained and experienced qualitative researcher and conducted by CP, MK, and SO. Research procedures for anonymity, rigor, validity and reliability included: verbatim transcriptions; de-identification; content analysis of keywords, phrases and patterns; ongoing team discussion; consensus of descriptions; and final agreement on categories and themes. Data analysis was managed with Word© documents on a protected shared drive, with independent and shared analysis to minimize predetermined coding and anticipation of findings. Extensive personal experiences were shared with rich data across participant groups. Meaningful saturation was evident in emerging categories and repeating themes across and within responses. 20

Ethics Approval and Funding

The study was approved by the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (HREB; #Pro00066208).

Results

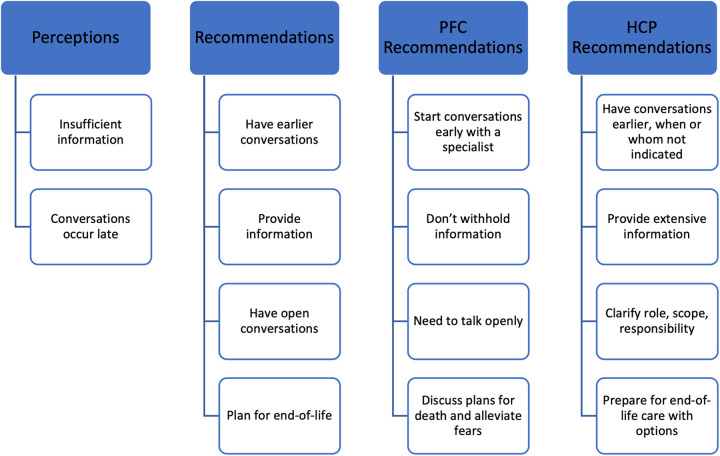

Twenty participants were interviewed between July 20 and August 16, 2016 (Table 1). No participants withdrew. Detailed and rich descriptions of ACP perspectives and experiences were analyzed. Two categories, perceptions and recommendations, were identified with themes (Figure 1). Quotes were selected to exemplify findings and diversity of participant perspectives (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Interviews.

| Patients, family caregivers (PFCs) (n = 10) length of interviews (Minutes): Range: 11.31-31.09; Median 26.58 | Health care professionals (HCPs) (RN, NP, RRT, MD) (n = 10) length of interviews (Minutes): Range: 11.49-31.09; Median 20.14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Caregivers | Home care (HC) | Acute care (AC) | |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Median age (Range) | 69 (58-78) | 65 (20-73) | ||

| Male (%) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | ||

Abbreviations: RN, registered nurse; NP, nurse practitioner; RRT, registered respiratory therapist; MD, doctor of medicine.

Further details not provided to protect anonymity.

Figure 1.

Categories, themes and subthemes identified from participant responses. PFC, patient and family caregiver participants; HCP, health care professional participants.

Table 2.

Quotes That Exemplify the Findings.

| Category 1: perceptions | |

| Themes | Exemplary quotes |

| Insufficient information (Both PFCs and HCPs) | I understand the issues, but I have trouble defining or clarifying exactly how the levels [work]. I really don’t want to end up in ICU. So, that’s clear. On the other hand, if I get pneumonia am I not going to get antibiotics?…So, where do you draw the line? (P4) |

| It was so hard to find information and any doctors or nurses we did talk to had never had a patient with IPF before. So what they maybe heard about or they were comparing it to COPD or other diseases that it really can’t be compared to. There was no information and it was really hard to find and it felt like we were completely on our own…From what I found online, it was scary; but I figured if that was the case, then her doctor would tell us. (C4) Even though you look at the internet for everything, you don’t know what is right and what isn’t. You kind of take it with a grain of salt. Some information from a doctor, you know, is fact for me. Even some sites to go to, where you can read more in depth. So, you know you can trust that site. (C1) The family had no idea about his condition. They didn’t understand what pulmonary fibrosis was. He had had it for several years. So when I arrived, because he was new to Home Care, I asked the family, “Why is he not on oxygen?” And his respirations were 57 a minute. (HCP2 HC) I think, most of the conversations I’ve had, we don’t get right to the end. We talk more about the progression of it. Of their disease and how they’re going to manage as they get more and more dependent on oxygen. If I’m working with Dr. J, she usually has that conversation. Or the other respirologist. A lot of times people are delusional. Even at the end stage. (HCP6 HC) I think lung transplant for a lot of people is an option to be on the list but they need to know the reality that how many people actually [get] transplants and that is not exactly just an easy fix and you are all better afterward. They need a lot of information on that and I’m sure they get a lot; but they need a lot of information on what drugs and how they work to relieve their shortness of breath, and what they do. They need to know about their oxygen requirements going up; their shortness of breath; the symptoms; what is going to be available for them; can they stay home with family members and be on oxygen or can they go to palliative care or hospital. I think they kind of need to understand all the options along the way and what needs to be done kind of, at what point and that there really is no timeline for it too. (HCP2 AC) | |

| Conversations occur late (Both PFCs and HCPs) | I had pleurisy between the layers of the lung. I ended up in hospital for a week on IV antibiotics and a chest tube. Plus they produced a Green Sleeve, which I’d never seen or heard about until then. I can see their point. They want to get it done before you end up needing resuscitation. But honest to god if you’re short of breath, got pains in your side and feeling lousy, it’s not necessarily the time to be asking you questions about levels of care. (P4) Usually, in my experience, it’s as their oxygen levels climb. They start to realize that they’re getting sicker. And that is often the only symptom. Within home care there is long term care and there’s palliative. We will try and get them referred to palliative and the palliative nurses will say “They don’t have any palliative symptoms.” They’ll have 9 out of 10 shortness of breath and they’re on 15L oxygen. (HCP6 HC) Usually the patients end up on BiPAP so we are spending more and more time with them (family) and usually they are unprepared, panicked, family is usually panicked and anxious and they are basically not prepared for what is happening. (HCP10 AC) Half the time they have no idea. They are blindsided. Like, “What are you talking about? They are end-stage?” or “I saw them yesterday and they were fine and now look at them.”…They are hypoxic, they are unconscious, and now the family is making their decision and the family doesn’t want to make their decision. And it’s like, well who the hell is going to make the decision? (HCP3 AC) He wanted to wait until the last possible second to still be on the Transplant List just in case and the family knew that any moment could be his last and I think he knew that too; but he was still hanging upon hope for a transplant and refusing Dilaudid. It was horrible to watch and the RTs were very frustrated to watch him pass away like this when we knew he could pass away much more peacefully. It was not a good situation at all because they were just so scared and it just happened so fast and they were completely unprepared…To me there was no clear conversation or direct conversation about where he was actually heading. Like everyone seemed to know that he was going to be passing away soon and was deteriorating very quickly; but the family was thinking that they were going to get a transplant and that was all they could see. And so there was no proper planning; there was no preparation for his death. Like he had a very traumatic breathless death and it was awful. (HCP10 AC) |

| Category 2: recommendations, themes, subthemes | |

| Themes • Subthemes |

Exemplary quotes |

| Have earlier conversations (PFCs) • Start conversations early with a specialist |

I don’t think the GP knows enough about IPF to be honest because in my experience, they have heard of it but they might have one patient with it but it seems like by the time people are diagnosed, they are too far gone; or it just seems like it’s getting easier to diagnose. So I don’t know if they really have seen it enough to be able to have that conversation.…even the Palliative Care Nurse didn’t know about the oxygen testing and didn’t know about lung disease at all. And I guess it’s kind of like a GP—they know a little bit about a lot of things but respiratory issues are probably just going to keep getting worse—like respiratory illness. So I think they need to be more educated. (C4) |

| Have earlier conversations (HCPs) • Earlier conversations, when or whom not specified |

I think they need to know that they have a disease we know very little about, that can present itself with a lot of challenges to control symptoms, that the symptoms they can expect down the line are such, most types of ILD are not curable, they are progressive (HCP1 HC) I think she wasn’t prepared. She didn’t see herself as palliative. The respirologist involved kept saying “Just send her to acute.” The client had expressed the desire to die at home. But the respirologist involved wasn’t treating her like she was palliative, so didn’t have in place any kind of crisis dyspnea management or orders for how she could be managed at home while actively dying. (HCP6 HC) When they come in on XXX, they are critical and they are usually at the end so we have to be very blunt about it but that is usually when the conversation happens and it should have happened a long time ago or at the beginning when they were diagnosed (HCP3 AC) |

| Provide information (PFCs) • Don’t withhold information |

I think everything should be addressed. Because, everybody has a different question to ask. And different opinions. There’s so many facets to a terminal disease that you don’t even think about before you’re diagnosed. There’s a million different things. And every day is different, and every day brings tears or it brings joy. It’s really hard…By being honest. By laying it on the line and telling me this is what we do. This is what we can do. This is what could happen. That’s what I need to know…Laying it out. Being honest and telling me what’s going to happen. It’s very important. It’s one of my biggest fears. But now that I know a bit more about it I go to a support group that Dr. J spoke about…and she spoke about it, and I do feel much better just knowing. I was afraid of the end. Of how violent it could be. From things that I’ve heard and one man that I know who passed away with Dr. K and Dr. J, it was very calm and very reassuring. (P3) I found it a lot easier to have those conversations when we were both given the same information because if one of you is at home and one didn’t really want to upset the other one by telling them what you heard; but if you are both there and both hear the same things, it made it easier to talk about…this disease doesn’t hold back so I don’t think the pamphlet should either. It might be scary to some people but it is what they need to hear. (C4) |

| Provide information (HCPs) • Provide extensive information |

I prefer to give them all the information and let them pull what they will from it. And based on their knowledge, we can focus on the aspects that they’re lacking. I think that it’s better to have it all available. And reel in on the ones where you see a need for education. Versus only offering them what you think they need. You don’t know who’s going to read it in the evening when you’re not there. They could take something from it that you don’t know. I would rather that they have all of the information and you can use it later on as a tool. You could go back and refer to pages x, y, z of the toolkit to go over that. I think people have a right to know it all. They can make their choices based on that. (HCP1 HC) I think as much information provided is good. I don’t think anything should not be talked about. But I think when people choose to have more care, I think they really need to understand what that means. Like even BPAP, I find, is this thing that is not talked about and then you get to the end zone and then you BPAP the person basically until they pass away. Which is—it is supposed to be for comfort—and it is not comfortable and things like that. What ICU means—it’s not just a breathing tube down the throat—it’s much more than that. (HCP10 AC) |

| Category 2: recommendations, themes, subthemes | |

| Themes • Subthemes |

Exemplary quotes |

| Have open conversations (PFCs) • Need to talk openly |

So I mean we were terrified to have those conversations but once we knew for sure that was what was happening, we made it a point to talk about it openly and talk about her fears and concerns and that was huge. That was one thing that Dr. J and [Dr. K] nailed was being up front. “What do you want your death to look like? How do you want to die? What scares you the most about it?” And for my mom it was—she didn’t want to be drugged. She wanted to be conscious right until she couldn’t be anymore so they kept that in mind when dealing with her (C4). |

| Have open conversations (HCPs) • Clarify role, scope, responsibility |

I think everyone should have the conversation; some people feel more comfortable with it; others do not even want to approach it. Some people like to say, “well it’s in my scope; it’s not my scope.” (HCP3 AC) Failure to recognize and I think- well I don’t know what it is like to have that conversation. I’m not a doctor so I don’t have as much responsibility on me to talk about death and dying but they were dancing around it for sure. They were definitely not direct enough at all. The family needs to be told because in the end it’s like, I get you are upset and you are in denial about this but he is dying now and you are doing a disservice to the patient by not getting them to understand that because he had a horrible death. (HCP10 AC) |

| Plan for end-of-life (PFCs) • Discuss plans for death and alleviate fears |

the fact that at the end, the biggest part of suffering can be eliminated with the care plan. Because that was my biggest fear. Well, what do I do? Do I just go into hospital and I just gasp until I die? But, being reassured by them that I can have a home death, there can be drugs that can help to calm me down, and people there…Yes. And how caring and supportive the doctors can be. That there are drugs, medications that they can give you to calm you down, so it’s not scary at the end. (P3) And where you want to die and what the different types of experiences look like—so dying in a hospital versus a hospice versus at home. And with each of those different scenarios—the positives and negatives about it…So it is really just about having those conversations and so people know what to expect and they are not blind-sided by it and making sure that the hospice is willing to work with them. And if they are going to stay at home, what resources are available to them? (C4) |

| Plan for end-of-life (HCPs) • Discuss plans for death and alleviate fears |

I think there is a lot of fear with the changes that that body goes through when someone is like actively dying; the noises people make and the way people look. That would prepare people—like what is normal and what is alarming. It would give them some knowledge to face those things with less fear. (HCP4 AC) I think that it’s very important to educate the patient. But I think that it’s also very important to educate family physicians, so that they know how to manage ILD…Just through her level of dyspnea, her respiratory rate, her accessory muscles. All the indications of dyspnea. In addition to her low oxygen levels. Low oxygen sats, high oxygen flow. I could just tell she wouldn’t be able to manage at home for long. (HCP6 HC) |

Abbreviations: PFCs, patient and family caregiver participants; HPCs, health care professionals.

Perceptions

Both groups shared the themes in this category: “insufficient information” and “conversations occur late”.

Insufficient information

Patient and family caregiver participants (PFCs) had challenges in obtaining and understanding ACP information. Some understood they had to do something but did not know what to do or how to prepare. One stated, “My wife did a lot of digging on her own to find it” (C3). PFCs indicated they had poor overall understanding of choices. One caregiver with previous experience indicated she understood most issues.

PFCs also found it challenging to find or trust resources, even when directed to the internet: “My wife keeps looking on the internet and we were advised to get as much information as possible off the web. And there’s loads of information. They’re not sure exactly what it is, but one thing they are sure, it’s fatal.” (P1). A few described the internet as bad or scary, and most were uncertain about the accuracy of information: “I actually didn’t find it reliable” (P4).

HCPs perceived PFCs did not have sufficient information about the disease or its trajectory. They agreed many HCPs do not have the conversations. One suggested patients were afraid or did not know how to ask questions, especially near end-of-life.

Conversations occur late

HCPs from all disciplines and both settings perceived ACP conversations occurred “quite late in the trajectory of their illness” (HCP8 HC). Even when the disease was rapidly progressing, the severity was not necessarily recognized. At times, conversations and goals of care orders (GOCs) were just in time to support patient wishes. One NP went to see a client “right away because I was afraid he would pass away” (HCP2 HC). It was positive when conversations were in time: “I had a lengthy conversation with her the first day I met her, because I knew she would not last long.” (HCP1 HC)

HCPs were concerned when near-death events occurred without patient or family caregiver readiness. “Usually they are unprepared, panicked, family is usually panicked and anxious and they are basically not prepared for what is happening.” (HCP10 AC). Rapid deterioration with no plan for complicated symptom management and end-of-life care was distressing for patients, family and HCPs.

Recommendations

There was overlap and variation of themes in this category: “have earlier conversations”; “have open conversations”; “provide detailed information”; and “plan for end-of-life.”

Have Earlier Conversations

All participants recommended initiating ACP conversations earlier. PFCs were more specific as to when and with whom conversations should occur.

Start conversations early with a specialist

PFCs recommended conversations be initiated early in the disease, “I think at diagnosis, obviously, you need to be told that this is not curable and it’s progressive and it will end your life.”(P4). Four patient and two caregiver participants indicated professional expertise and knowledge was important: “A general practitioner is not up on it, it’s not their specialty” (P1). Diverse disciplines were recommended: “An IPF specialist, maybe a nurse practitioner in IPF. Or a respiratory therapist who focuses only on IPF, or it’s in her role. Someone who’s really knowledgeable about it.” (P4).

Earlier conversations, when or whom not specified.

HCPs also recommended having conversations earlier, and debated who should have the conversations and when they should start. They focused on challenges when conversations did not occur earlier.

Provide Information

The second theme was provision of information. PFCs recommended information not be withheld, whereas HCPs recommended extensive information be actively provided.

Don’t withhold information

PFCs sought information about their disease, quality of life, care options, symptom self-management, and alleviation of fears. They emphasized the importance of information and perceived HCPs withheld it. Caregivers emphasized the significance of knowing, not “holding back” (C4), even when dwelling on the finality of the disease. C5 described “the necessity for ACP” and how “important this planning is.” Some caregivers indicated they needed more information, or more often, than the patient to plan, “so no, don’t hold back” (C1).

Provide extensive information

HCPs recommended providing extensive information, then letting patients determine what they need to know more about. They noted specific questions may be challenging, primarily about fears and symptoms. Examples of “main questions” patients asked were: “Am I going to suffocate to death?”; “Is my breathing ever going to get better?”; “How am I going to be comfortable?” (HCP7 HC). No HCPs reported PFCs asking about intubation or resuscitation although AC HCPs noted the importance of discussing these, including non-invasive ventilation.

Have Open Conversations

The third theme described the context and processes that enable or challenge conversations.

Need to talk openly

PFCs recognized the uncertainty of the disease and their situations, and did not expect specifics. ACP conversations were reassuring, enabled planning and alleviated fears. Desired information included: “What’s likely to happen. I realize things can’t be black and white, but they can be a little bit more defined” (P4). Most perceived physicians and nurses would initiate conversations.

Clarify role, scope, responsibility

HCPs agreed with earlier and ongoing ACP, however, there was uncertainty about who was to initiate conversations. They indicated conversations should occur “continuously” with various professionals as the disease progressed (HCP4 AC). One recommended “specialists should explain it to them and the nurse, the home care nurse and kind of in that order.” (HCP9 HC)

Roles, scope, and responsibilities were unclear and challenging among acute care HCPs. Several suggested family physicians should lead conversations, because they know the patients, but then acknowledged, physicians say “specialists should be having these conversations.” Subsequently, conversations may occur “unfortunately for many patients, in the middle of a crisis in the Emergency Department” or “at the very, very end.” (HCP5 AC) Even when confident to have conversations, acute care professionals suggested physicians should initiate them, and expressed uncertainty about their roles, “I do feel confident; but in my place for it to be appropriate for me to talk about it. I don’t really know where I fit in to be honest.” (HCP10 AC) Although most professionals in acute care had had conversations, all perceived they occurred late or in a crisis: “It is usually when they are too critical and it’s at the end.” (HCP3 AC)

Home care HCPs discussed having a relationship with the person, “building trust” (HCP2 HC) and having rapport. Most thought conversations should not “fall on one person.” One expressed that all involved in the client’s care “has a responsibility to assess the level of knowledge and to assess their level of preparedness.” (HCP1 HC).

Plan for End-of-life

Although ACP is broader than end-of-life, all participants had recommendations for this aspect.

Discuss plans for death and alleviate fears

All PFCs recognized IPF as a terminal disease. They sought information to understand and prepare for disease progression. Information provided hope, encouragement and quality of life: “I want to know what to expect, what’s coming down the line. To me, I think that is something that should be at the beginning” (C5). P3’s home death care plan alleviated his fears and he did not “want to go into a hospital and have them do something totally different.” Caregivers recommended information be provided about different scenarios and options for end-of-life, resources, access and contacts, and how to “navigate the system” (C5).

Prepare for end-of-life care with options

HCPs recognized the value and importance of end-of-life conversations including symptom management, preferred place-of-death, and available resources. Options and “all of the alternatives to hospitals are not really brought forward as much as they could be” (HCP10 AC). If a home death is preferred, people need to be prepared: “it will take some work and it will take some preparation” and “not everybody can die at home” (HCP2 HC). Several HCPs recommended specialized knowledge for this population to support conversations, including quality of dying and end-of-life care. They noted that family physicians needed to be prepared and educated.

Discussion

PFCs in our study desired open, honest communication, and expected HCPs to initiate conversations early. Similar to other studies, these PFCs lacked understanding of care choices 8,21 and described insufficient ACP information and resources. 21,22 They preferred to engage with knowledgeable and experienced professionals, which also aligns with previous findings. 23 -25 In contrast, some HCPs perceived patients and caregivers were afraid to ask questions, unsure or hesitant to engage in ACP conversations. This contradiction is described in the literature, where patients and professionals perceive the other as reluctant and expect the other to initiate ACP conversations. 14,26 Both groups agreed on ACP topics, in contrast to Rozenberg et al who reported health professionals ranked IPF drug therapy as an important information topic whereas patients and caregivers ranked end-of-life care as important. 27 Clinicians need to recognize the benefits of discussing ACP and consciously engage in early conversations. 28,29 Overall recommendations for ACP topics, timing, and context align with previous studies. 17,30,31 Similar to You et al, prognosis, identifying values, addressing fears or concerns and end-of-life care preferences were included. 32 Desired end-of-life topics included symptom management, non-invasive ventilation and place of care options. Some caregivers identified they wanted or needed additional information for planning, thus caregivers may require tailored information at different times. 4

All participants recommended providing detailed and extensive information, although not their experiences. Most patient participants expressed wanting to learn about end-of-life, signifying the importance of this topic, regardless of the severity of IPF. Many patients may ask about timelines but expect information on the dying process, care options, dyspnea management, and want hope and support for themselves and their families. When conversations extend beyond do-not-resuscitate orders to address fears, elicit goals, values and preferences, and provide reassurance that symptoms may be managed, they facilitate planning, enable a shift to focusing on making memories and accomplishing goals, and bringing meaning and dignity when living and dying with IPF. 4 Kylmä et al reported that providing honest information about the patient’s illness can contribute to patient hope; death and dying conversations give patients a sense of control and lessen their fears. 33 Learning about end-of-life options may enable patients to make informed choices and decrease risk of acute or critical care deaths. Most ILD patients prefer home or hospice deaths, thus planning for symptom self-management, home care support and knowledge of preferred place of death is essential. 34 Knowledge of end-of-life home or hospice care options, competency in refractory breathlessness management, and collaboration between physicians and community teams are paramount to providing patient-centered care and good quality of death and dying in IPF.

With limited treatment options and an unpredictable trajectory, IPF patients may feel more confident about their plans and worry less about future symptoms when informative and wholesome conversations are held early, so they can focus on living life in the time they have left. 26,35 Of importance, HCPs relayed distress at death, similar to Bajwah et al. 8 Lack of ACP is a missed opportunity and failure for this patient population globally. 10 -12

There were notable differences in HCP perceptions between care settings; home care HCPs engaged in conversations independently and confidently within their roles. Acute care HCPs indicated confusion of roles and responsibilities that impeded engagement in ACP conversations. Lack of role clarity has been described as an important barrier to ACP. 36 Al Hamayel and colleagues suggested older patients may require time to conceptualize their wishes before documenting them or engaging with others. 37 Introducing concepts earlier in primary care may be a useful strategy for IPF patients who are referred to specialty clinics, home care or transplant programs where conversations are continued.

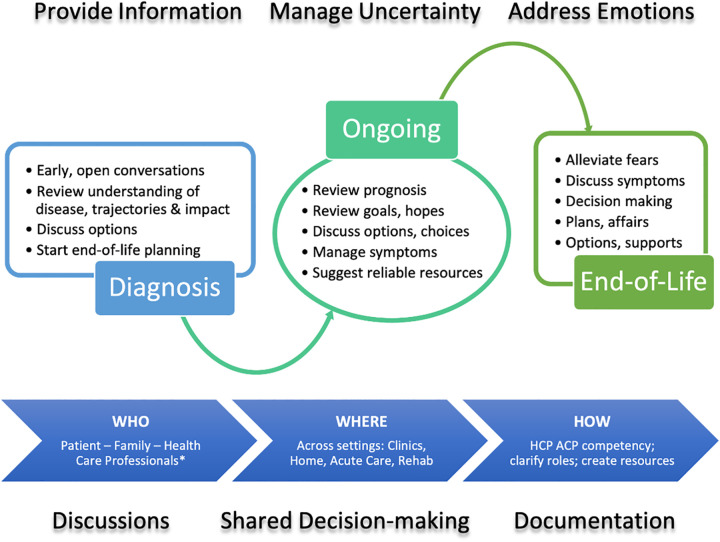

PFCs recommended formal training which aligns with other recommendations. 38 Communication skills can be learned as any other clinical skills, with numerous programs ranging from seminars to workshops and online learning platforms, such as the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG) and The Conversation Project. 39 SICG includes exploring the patient’s understanding of their illness, then their wishes, priorities, fears, strengths and prognosis. Other evidence-based models of patient-clinician communication emphasize prioritizing ACP conversations, making time to establish a rapport, eliciting patient perspectives, concerns, and wishes, explicitly demonstrating empathy and engaging in shared decision-making. 40,41 The SPIKES approach recommends setting up the conversation, assessing patient perception, obtaining patient invitation to engage in discussion, providing individualized information and knowledge, addressing emotion with empathy, and ending with providing a strategy and summary that is easily understood. 42 From the literature and these findings, we propose a framework for ACP discussions in IPF to guide clinicians in implementing early, meaningful conversations (Figure 2; Table 3). ACP conversations are prioritized, fears regarding death openly addressed; patients and families empowered through self-management strategies and information; and connections to support groups and home care facilitated. Caregivers are engaged at each and every step through invitation to attend clinics and participate in decision-making. This approach includes the core components highlighted in the National Cancer Institute’s commissioned monograph on patient-centered communication in cancer. 43

Figure 2.

Framework for ACP discussions in IPF. HCP, health care professional participants; ACP, advance care planning. * Specialist and primary care physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, allied health.

Table 3.

Framework: Individualized Advance Care Planning Conversations With IPF Patients and Caregivers.

| Prioritize | Prioritize and make time

|

| Preparation | Prepare to have the conversation

|

| Information | Provide information

|

| Intentionality | Respond to verbal and non-verbal cues

|

| Perspective | Manage uncertainty

|

| Engagement | Engage both patients and caregivers in collaborative decision making

|

| Enablement | Enable patient self-management through symptom actions plans

|

| Ongoing | Foster healthy and trusting relationships

|

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; HCP, health care professional; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Strengths and Limitations

Ethnic and cultural diversity were unintentionally limited in both participant groups; the majority were Caucasian. Some HCPs had previous training and support from specialists in an integrated palliative approach for IPF, and therefore expected to have more confidence and experience in ACP conversations. Strengths include the rich descriptions from perspectives of PFCs and HCPs from both acute and community settings. This is the first known study that revealed the distress and burden experienced by HCP in hospital settings where HCPs perceived palliative needs were neither identified nor openly discussed, and indicated the opportunity for ACP to improve end-of-life care.

Conclusion

Advance care planning is desired by patients and caregivers living with IPF, encouraged by HCPs, although numerous challenges and barriers exist. Potential for distress at end-of-life emphasizes the need for early ACP conversations. HCPs should discuss available end-of-life options, including home and hospice. Recognition by HCPs that ACP is more than do not attempt resuscitation orders, but a holistic communication process that addresses symptoms, psychosocial and emotional needs, relieves fears, promotes hope and elicits engagement, may in turn address HCP concerns of taking away patient hope. Practical guidance and training to improve HCP competency and confidence in ACP are needed, in addition to clarity within organizations as to scope, policy and responsibilities.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ajh-10.1177_10499091211041724 for Advance Care Planning Needs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Qualitative Study by Meena Kalluri, Sara Orenstein, Nathan Archibald and Charlotte Pooler in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-ajh-10.1177_10499091211041724 for Advance Care Planning Needs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Qualitative Study by Meena Kalluri, Sara Orenstein, Nathan Archibald and Charlotte Pooler in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: CP, SO and MK contributed to the study design. SO collected the data. CP, SO and MK analyzed the data. All authors contributed to data interpretation, drafted, revised and approved the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding was provided by the University of Calgary 2016 Summer Studentship of the Health Professions Education Grant Program.

ORCID iD: Nathan Archibald  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7277-5126

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7277-5126

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Kim HJ, Perlman D, Tomic R. Natural history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2015;109(6):661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindell KO, Kavalieratos D, Gibson KF, Tycon L, Rosenzweig M. The palliative care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study of patients and family caregivers. Heart Lung. 2017;46(1): 24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Egerod I, Kaldan G, Shaker SB, et al. Spousal bereavement after fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study. Respir Med. 2019;146:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pooler C, Richman-Eisenstat J, Kalluri M. Early integrated palliative approach for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a narrative study of bereaved caregivers’ experiences. Palliat Med. 2018;32(9):1455–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, Van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, et al. Specialist palliative care is more than drugs: a retrospective study of ILD patients. Lung. 2012;190(2):215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et al. “I wish I knew more…” the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers and health professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(1):84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Manen MJ, Kreuter M, Van den Blink B, et al. What patients with pulmonary fibrosis and their partners think: a live, educative survey in the Netherlands and Germany. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3(1):00065–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smallwood N, Mann J, Guo H, Goh N. Patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease receive supportive and palliative care just prior to death. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2021;38(2):154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akiyama N, Fujisawa T, Morita T, et al. Palliative care for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: pulmonary physicians’ view. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(5):933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindell KO, Liang Z, Hoffman LA, et al. Palliative care and location of death in decedents with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2015;147(2):423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JY, Tikellis G, Corte TJ, et al. The supportive care needs of people living with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(156):190125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jabbarian LJ, Zwakman M, van der Heide A, et al. Advance care planning for patients with chronic respiratory diseases: a systematic review of preferences and practices. Thorax. 2018;73(3):222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, et al. The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):869–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoenheit G, Becattelli I, Cohen AH. Living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8(4):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morisset J, Dubé BP, Garvey C, et al. The unmet educational needs of patients with interstitial lung disease. Setting the stage for tailored pulmonary rehabilitation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(7):1026–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Overgaard D, Kaldan G, Marsaa K, Nielsen TL, Shaker SB, Egerod I. The lived experience with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1472–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goobie GC, Guler SA, Johannson KA, Fisher JH, Ryerson CJ. YouTube videos as a source of misinformation on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(5):572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fisher JH, O’Connor D, Flexman AM, Shapera S, Ryerson CJ. Accuracy and reliability of internet resources for information on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russell AM, Ripamonti E, Vancheri C. Qualitative European survey of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: patients’ perspectives of the disease and treatment. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Masefield S, Cassidy N, Ross D, Powell P, Wells A. Communication difficulties reported by patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their carers: a European focus group study. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5(2):00055–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holland AE, Fiore JF, Jr, Goh N, et al. Be honest and help me prepare for the future: what people with interstitial lung disease want from education in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Res Dis. 2015;12(2):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall A, Rowland C, Grande G. How should end-of-life advance care planning discussions be implemented according to patients and informal carers? A qualitative review of reviews. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(2):311–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rozenberg D, Sitzer N, Porter S, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a review of disease, pharmacological, and nonpharmacological strategies with a focus on symptoms, function, and health-related quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(6):1362–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janssen K, Rosielle D, Wang Q, Joo Kim H. The impact of palliative care on quality of life, anxiety, and depression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomized controlled pilot study. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hjorth NE, Haugen DF, Schaufel MA. Advance care planning in life-threatening pulmonary disease: a focus group study. ERJ Open Res. 2018;4(2):00101–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramadurai D, Corder S, Churney T, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: educational needs of health-care providers, patients, and caregivers. Chron Respir Dis. 2019;16:1479973119858961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, et al. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. CMAJ. 2014;186(18): E679–E687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kylmä J, Duggleby W, Cooper D, Molander G. Hope in palliative care: an integrative review. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):365–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iyer AS. The “good” home death in pulmonary disease: avoiding the “bad” and the “ugly”. Chest. 2020;158(2):449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reinke LF, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Transitions regarding palliative and end-of-life care in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer: themes identified by patients, families, and clinicians. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shaw M, Hewson J, Hogan DB, Bouchal SR, Simon J. Characterizing readiness for advance care planning from the perspective of residents, families, and clinicians: an interpretive descriptive study in supportive living. Gerontologist. 2018;58(4):739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Al Hamayel NA, Isenberg SR, Sixon J, et al. Preparing older patients with serious illness for advance care planning discussions in primary care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(2):244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. Primary Care Toolkit—National. 2015. Last Updated October 22, 2020. Last Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.advancecareplanning.ca/resource/primary-care-toolkit/

- 39. The Conversation Project. Advance Care Planning. 2016. Last Accessed August 17, 2021. https://theconversationproject.org/nhdd/advance-care-planning/

- 40. Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. Perm J. 1999;3(3):79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(1):4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care. Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. National Cancer Institute; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Last Updated October 2007. Last Accessed January 25, 2021. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ajh-10.1177_10499091211041724 for Advance Care Planning Needs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Qualitative Study by Meena Kalluri, Sara Orenstein, Nathan Archibald and Charlotte Pooler in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-ajh-10.1177_10499091211041724 for Advance Care Planning Needs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Qualitative Study by Meena Kalluri, Sara Orenstein, Nathan Archibald and Charlotte Pooler in American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®