Abstract

Improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) is a very important goal of crop breeding throughout the world. Cassava is an important food and energy crop in tropical and subtropical regions, and it mainly use nitrate as an N source. To evaluate the effect of the nitrate transporter gene MeNPF4.5 on the uptake and utilization of N in cassava, two MeNPF4.5 overexpression lines (MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34) and one MeNPF4.5 RNA interference (RNAi) line (MeNPF4.5 Ri-1) were used for a tissue culture experiment, combining with a field trial. The results indicated that MeNPF4.5 is a plasma membrane transporter mainly expressed in roots. The gene is induced by NO3–. Compared with the wild type, MeNPF4.5 OE-22 exhibited improved growth, yield, and NUE under both low N and normal N levels, especially in the normal N treatment. However, the growth and N uptake of RNAi plants were significantly reduced, indicating poor N uptake and utilization capacity. In addition, photosynthesis and the activities of N metabolism-related enzymes (glutamine synthetase, glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase, and glutamate dehydrogenase) of leaves in overexpression lines were significantly higher than those in wild type. Interestingly, the RNAi line increased enzymatic activity but decreased photosynthesis. IAA content of roots in overexpressed lines were lower than that in wild type under low N level, but higher than that of wild type under normal N level. The RNAi line increased IAA content of roots under both N levels. The IAA content of leaves in the overexpression lines was significantly higher than that of the wild type, but showed negative effects on that of the RNAi lines. Thus, our results demonstrated that the MeNPF4.5 nitrate transporter is involved in regulating the uptake and utilization of N in cassava, which leads to the increase of N metabolizing enzyme activity and photosynthesis, along with the change of endogenous hormones, thereby improving the NUE and yield of cassava. These findings shed light that MeNPF4.5 is involved in N use efficiency use in cassava.

Keywords: cassava, nitrate transport, nitrogen efficiency, growth, MeNRT1.1/MeNPF4.5

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is one of the three major root and tuber crops in the world, and it is the sixth largest food crop globally. It is known as the “underground granary” and “king of starch” because of its importance as a source of food, feed, and industrial processing material, and it is also an important energy crop (Zhuang et al., 2011). Nitrogen (N) is the major limiting factor for cassava yield. Fertilizers are necessary for increasing storage root yields, and thus excessive amounts of N fertilizer may be applied to obtain high yields. However, the N use efficiency (NUE) has decreased from 68 to 47% over the past 50 years (Lassaletta et al., 2014), and more than half of the N applied is lost to the environment. Excessive application of N fertilizer results in leaching of N from farmlands through surface runoff and water pollution (Li et al., 2017; Kyriacou et al., 2018). Because of this, reducing the amount of N fertilizer and improving the NUE of crops have become increasingly important goals for breeders. This is also the case for cassava, where improving the efficiency of N uptake and use is of important theoretical and practical significance for improving the ecological environment, ensuring food safety, and addressing food shortages due to population growth.

Most plants use nitrate (NO3–) as the main source of N (Wang W. et al., 2018). NO3– is a nutrient that regulates plant growth and development (Fenchel et al., 2012), and it also acts as a signaling substance regulating gene transcription, thus affecting seed germination, plant root growth, and leaf stomatal activity (Wang et al., 2012). The uptake and transport of NO3– in the roots and its redistribution among cells are realized through NO3– transporters (NRTs). By using isotopic tracers 13N and 15N, two NO3– transport systems have been found in higher plants: the high-affinity transport system, which mainly functions under low external NO3– concentrations (<0.50 mM), and the low-affinity transport system, which mainly functions under high external NO3– concentrations (≥0.50 mM) (Miller et al., 2007; Wang Y. Y. et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2019). High- and low-affinity NRTs are encoded by the NRT2 and NRT1 gene families, respectively. The Nitrate Transporter 1 (NRT1) gene family got its name because it was originally found to have the function of transporting NO3–, the function of transporting dipeptides was found later and then was further classified as the PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER (PTR) family. However, several studies in the past few years confirmed that an even wider range of molecules are transported by some family members (Zhou et al., 1998; Jeong et al., 2004). Léran et al. (2014) renamed it as NPF (NRT1/PTRFAMILY) family according to its systematic evolutionary characteristics. Currently, 53 NRT1/PTR family members and seven NRT2 family members have been found in Arabidopsis thaliana (Okamoto et al., 2003). AtNRT1.1 also known as CHL1 and AtNPF6.3, was the first member identified as a low-affinity transporter, but it also functions as a high-affinity transporter at low external NO3– concentrations depending upon its phosphorylation state (Liu et al., 1999; Ho et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2014). It plays a key role in sensing and triggering many adaptive changes in response to external NO3–, such as stimulating lateral root elongation in NO3– rich patches (Remans et al., 2006). NRT1.1 can activate these responses through many independent mechanisms, which can be uncoupled by introducing point mutations in different regions of the protein (Bouguyon et al., 2015). In addition to NO3– uptake, NRT1.1 regulates the expression of many NO3– responsive genes (Undurraga et al., 2017). Furthermore, NRT1.1 is a master player in the NO3– mediated regulation of root system architecture because it stimulates the growth of lateral roots and tap roots of Arabidopsis (Remans et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2017; Maghiaoui et al., 2021). Some NRT1 family proteins transport NO3– and other diverse compounds, such as nitrite (Sugiura et al., 2007), amino acids (Zhou et al., 1998), peptides (Komarova et al., 2008), and phytohormones including auxin (Krouk et al., 2010), gibberellin (Tal et al., 2016), and abscisic acid (Kanno et al., 2012), which indicates that they have versatile functions.

At present, NRT/NPF genes have mainly been identified in A. thaliana and rice, and their functions and regulatory mechanisms have been studied in detail (Liu et al., 2015; Sakuraba et al., 2021). For example, studies have shown that rice NRT1.1B is located in the cell membrane and plays an important role in the transport of NO3– from the adventitious roots to the leaves (Hu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2017). Cassava is an allodiploid species (2n = 36) with a highly heterozygous genome, therefore, the function and expression of NRT genes in cassava deserve our attention. MeNRT2.1 of cassava was found to be mainly expressed in the root system, and transient expression experiments in protoplasts revealed that the MeNRT2.1 protein is localized on the cell membrane (Zou et al., 2019). Ren et al. (2019) discovered that the MeNRT2.5 gene was expressed in the roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and other organs, with relatively high expression in the roots of mature cassava plants and the leaves of tissue-cultured seedlings; and the expression of this gene was found to be inhibited by high concentrations of NO3–. Despite the progress in characterizing members of the NRT2 gene family, there has been no report on the NRT1 gene family in cassava. In this study, the MeNPF4.5 (MeNRT1.1) gene was identified and found to be mainly expressed in cassava roots. Overexpression of this gene in cassava improved the yield of storage roots by increasing the activities of enzymes related to N metabolism and enhancing photosynthesis. In contrast, RNA interference (RNAi) significantly decreased yield, which indicated that MeNPF4.5 plays a vital role in cassava growth by regulating the metabolism and distribution of N.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenetic Analysis of NRT1.1

For phylogenetic analysis of NRT1.1, amino acid sequences of NRT1 from different species were obtained from GeneBank and sequence alignment was carried out using DNAMAN software (version 9.0). A phylogenetic tree based on entire amino acid sequences was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 7.0 (Li et al., 2018).

Plasmid Construction and Cassava Transformation

Cassava MeNPF4.5 (GeneBank accession No. KU361329.1) was cloned from the root cDNA of TMS60444 seedlings, which was cultured in normal condition without NO3– induction. MeNPF4.5 was controlled by the CaMV35S promoter. The expression cassettes was inserted into the binary vector pCAMBIA1301 containing the hygromycin phosphotransferase under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter to generate pC-35S:MeNPF4.5. And a binary expression vector p35S:MeNPF4.5 was constructed according to previous report (Vanderschuren et al., 2009). The plasmids were mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404, and cassava TMS60444 was used as donor plant to produce transgenic plants. Transgenic plants were produced by reported methods (Zhang et al., 2000).

Subcellular Localization of MeNPF4.5 Protein

The open reading frame of MeNPF4.5 without a stop codon was amplified using MeNPF4.5 gene-specific primers (F: cagtGGTCTCacaacatgcttttcactggacttta; R: cagtG GTCTCatacaaacttgtatcaattcga cct) The PCR amplification product was cloned into the pBWA(V)HS-ccdb-GLosgfp vector to generate the MeNPF4.5-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) C-terminal fusion construct, and 35S-EGFP was used as a negative control. The recombinant plasmids were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation and then transformed into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Two days later, EGFP fluorescence was observed at 488 nm and chloroplast fluorescence was observed at 640 nm under a confocal laser scanning microscope (C2-ER, Nikon, Japan).

Southern Blot and qRT-PCR Analysis

Southern- blot analysis was carried out as described by Xu et al. (2012). Genomic DNA was extracted and digested with Hind III, separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel, and then transferred to a nylon membrane with a positive charge (Roche, Shanghai, China). The hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT) (1 kb) and MeNPF4.5 (1.5 kb) probes were labeled with digoxigenin. Hybridization and detection were performed with the DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Total RNA was extracted from different cassava tissues (100 mg each) using RNA Plant Plus Reagent (Tiangen Biotech, Co., Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the Prime Script™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Bio Inc., Kyoto, Japan). The specificity of the gene specific primers was verified by melting curve analysis. The cassava Actin gene was used as an internal control, and the 2–ΔΔCt method was used to calculate relative gene expression. The primer sequences were as follows: MeNPF4.5 (F: 5′-CCT CAA TTC CAG TGA TAC CTC TGC TTT-3′; R: 5′-GGA TTC CTG TGA TCT TCC GAA CCA AT-3′) and MeActin (F: 5′-CTC GTG TCA AGG TGT CGT GA-3′; R: 5′-GCC CTC TCA TTT GCT GCA AT-3′).

Cassava Tissue Culture Experiment

The tested materials were the wild-type cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) cultivar TMS60444 (WT), overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34, and RNAi line MeNPF4.5 Ri-1. The stems of WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava (with one sprout) were subcultured in 1/2 Murashige-Skoog (MS) (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) medium (Hope Bio-Technology, Qingdao, China) in a tissue culture room for 10 days. Germinated seedlings were then transferred in MS medium without N–NH4+, and the medium was supplemented with KNO3 as a sole N source at the concentrations as indicated in each individual experiment. Three NO3– treatments as follows, N-free: 0 mM, low-N: 0.5 mM, and full-N: 20 mM. For N-free and low-N conditions, ion equilibrium of the medium was ensured by replacing KNO3 by K2SO4. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 6.0 by using NaOH. The cassava seedlings were then incubated at 26°C and 50% relative humidity with a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle. Light intensity during the day period was 250 μmol m–2 s–1. The medium contained 25 g L–1 sucrose and 1 g L–1 Gelrite. The roots were cut at the distance of 1.5 cm from root tip, stems were cut at the distance of 1.5 cm from tip, and the second expanded leaves samples were harvested 25 days after treatment with NO3–, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further use.

Wild-type seedlings were grown in MS medium for 25 days and then transferred to hydroponic solution with 10 mM NO3–. After cultivation for 1 week, seedlings were transferred to 0.1 mM CaSO4 for 2 days and then to a complete nutrient solution containing 20 mM NO3–. Roots were harvested at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after treatment in 20 mM NO3–, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for qRT-PCR analysis.

Root NO3– Uptake

Wild-type and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava seedlings were grown in MS medium for 25 days and then transferred to hydroponic solution with 10 mM NO3–. After cultivation for 1 week, seedlings were transferred to 0.1 mM CaSO4 for 2 days and then exposed to various NO3– concentrations for 6 h. Roots were separated from shoots and measure the fresh root weight. Root NO3– uptake were determined by disappearance of NO3– from the nutrient solution. Their NO3– concentration was determined by using Flow Injection Analyzer (FIASTAR 5000, Foss Analytical, Höganäs, Sweden).

where V1 and C1 are the volume of the system and the NO3– concentration before experiment, and V2 and C2 are the volume of the system and the NO3– concentration after experiment. W is fresh weight of root. T = 6 h.

Field Experiment

Plant Growth Condition

Field experiment was performed in 2016 at Jiatapo, Dingxi Village, Pumiao Town, Nanning City (22°81’N, 108°63’E). The test soil was evenly flat and had uniform fertility. The chemical compositions of the cultivated soil layers before the experiment are listed in Supplementary Table 1. According to the NY/T1749-2009 Soil Fertility Diagnosis and Evaluation Method of Farmland in Southern China standards for total N (1.0 g kg–1) and available N (105 mg kg–1), the soil layers of the test plot were low in N.

A double factor split-plot design was used for field trial; the main and sub-plots were N treatment and cassava lines, respectively. There were two N treatments, low (0 kg ha–1, N0) and normal N (125 kg ha–1, N1), and the N fertilizer was urea (containing 46.7% N). A random block design was adopted with three replications. The same amounts of phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizers were used for all plots (P2O5 48 kg ha–1; K2O 162 kg ha–1). Super phosphate was used as a P fertilizer, and potassium chloride was used as a K fertilizer. The P fertilizer was applied once at sowing, while the N and K fertilizers were applied thrice: 50% as a base fertilizer, 25% at 40 days after sowing, and 25% at 90 days after sowing.

For the basal fertilizer application, a 10 cm deep groove was dug at a distance of 15 cm away from the cassava stem; all the basal fertilizers were applied evenly in this groove and covered with soil. For the top dressing, the fertilizer was dissolved in water and then applied quantitatively to each plant. The size of the subplot was 10 m2 (1 m × 10 m), and the distance between cassava plants was 1 m × 1 m. To prevent leaching of the fertilizer from the N1 plot to the N0 plot, the two N treatment plots were separated by 1 m. The cassava plants were planted on May 10, 2016, and conventional field management methods were used during the entire growth period. Plants were harvested for agronomic trait evaluation and subsequent experiments on January 10, 2017.

Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Metabolism Enzyme Assays

During the harvesting of cassava, the fresh weights of leaves, stems, and storage roots of individual plants were measured. A fixed amount of each component was collected and dried at 105°C for 30 min and then further dried at 65°C to a constant weight. Tissue N concentration was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method (Mishra et al., 2016) after digestion by concentrated H2SO4–H2O2.

The methods for calculating each indicator were as follows:

Dry matter mass of the whole plant (t ha−1) = dry storage root weight + dry stem weight + dry leaf weight (Kang et al., 2020).

N accumulation (g plant−1) = N content of the organ × dry matter mass of the organ (Kang et al., 2020).

Transport index (%) = Shoot N content/(Root N content + Shoot N content) × 100 (Léran et al., 2013).

Nutilization efficiency (kg kg−1) = Plant dry weight/N accumulation (Kang et al., 2020).

N recovery efficiency (kg kg−1) = (N uptake with fertilizer – N uptake with nofertilizer)/N application rate (Peng et al., 2006).

Partial factor productivity of N fertilizer (kg kg−1) = Storage root yield/N application rate (Peng et al., 2006).

The fifth expanded leaves from plants grown for 3 months were collected with three replications. The midrib was removed, and the sample was cut and mixed evenly to determine the activity of key enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism. Nitrate reductase (NR) activity was measured using a kit from the Nanjing Jian Cheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The activities of glutamine synthetase (GS), glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase (GOGAT), and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) were determined using the method described by Huang et al. (2015).

Leaf Photosynthesis and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters Analysis

The photosynthetic activity of the fifth expanded leaves from plants grown for 3 months was measured with a 6400XT (LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States) photosynthesis system on a sunny day from 9:00 to 11:00 in the morning. The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), stomatal conductance (Gs), and transpiration rate (Tr) were determined. The photosynthetic photon flux density was 1,200 μmol m–2s–1.

The following chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were recorded from leaves at the same position as those used for photosynthetic parameter measurements using an imaging chlorophyll fluorimeter (Walz Imaging PAM, Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany): Fv/Fm (PS II maximum quantum yield of photosynthesis), Y(II) (PS II actual quantum yield of photosynthesis), qP (photochemical quenching coefficient), and qN (non-photochemical quenching coefficient). The measurements were conducted at room temperature (25°C) using the standard saturated light mode. The actinic light intensity was 10 μmol m–2 s–1. Prior to detection, leaves were adapted to darkness for 30 min.

Endogenous Hormone Analysis

Cassava seedlings were cultivated in tissue culture under different N conditions (0.5 and 20 mM NO3–) for 25 days, and then the endogenous hormone content in the roots (excised from 1.5 cm of primary root tips) and leaves (the second expanded leaves) of WT and transgenic plants were analyzed. The extraction, purification and determination of endogenous hormones levels were assayed by an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique, which performed with a kit from the Beijing Benongda Tianyi Biotechnology Co. (Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Data from at least three biological replicates are presented as the mean ± SE. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by independent sample Student’s t-test was performed using SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Phylogenetic Analysis of NRT1.1 and MeNPF4.5 Is a Plasma Membrane Localized Protein

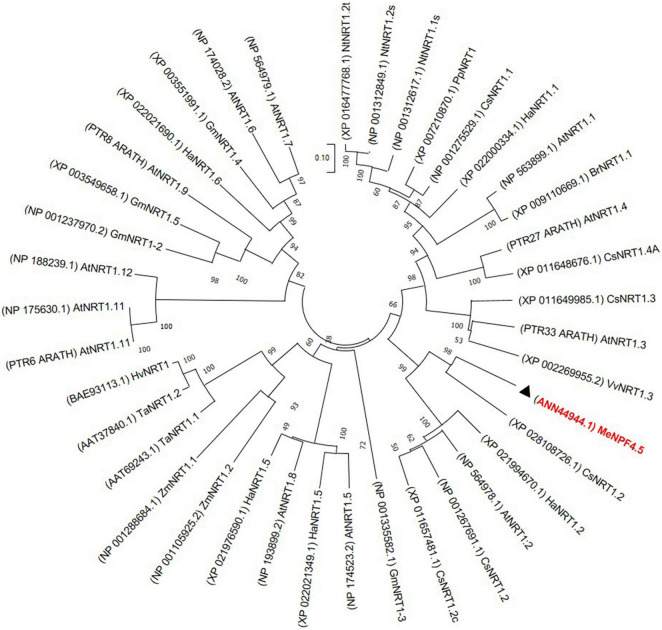

Phylogenetic analysis showed that MeNPF4.5 is closely related to CsNRT1.2 of Camellia sinensis and HaNRT1.2 of Helianthus annuus. These results showed that MeNPF4.5 is a member of the NRT1/NPF subfamily (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the MeNPF4.5 protein and other NO3– transporters (NRTs). The amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW software and the phylogeny was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA7.

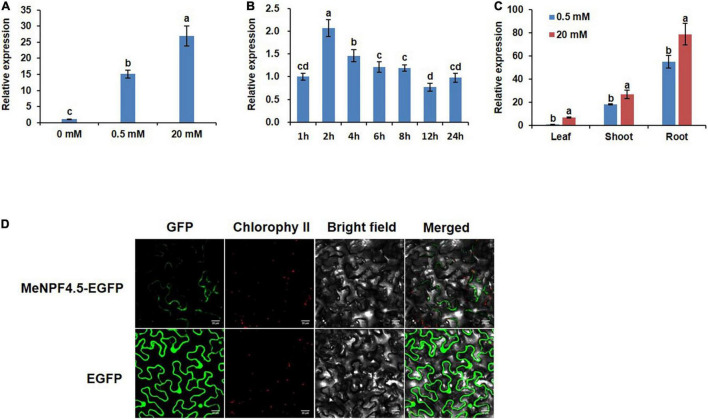

A 35S-MeNPF4.5-EGFP fusion protein construct was used to determine the subcellular localization of MeNPF4.5, and 35S-EGFP served as control. The constructs were transiently transformed into leaf cells of Nicotiana using agroinfiltration. MeNPF4.5-EGFP was expressed in the plasma membrane, whereas EGFP was detected not only in the plasma membrane, but also in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 2D). These results indicated that MeNPF4.5 is a transmembrane transport protein.

FIGURE 2.

Tissue-specific expression pattern and subcellular localization of the MeNPF4.5. (A) Relative expression of MeNPF4.5 in the roots of plants grown under different N conditions for 25 days. (B) Expression levels of MeNPF4.5 in N-starved roots at different times after N induction. Wild-type (WT) seedlings were grown in 10 mM NO3– for 20 days and under N starvation for 2 days, then were transferred to 20 mM NO3–. (C) Expression of MeNPF4.5 in various tissues of cassava. Cassava seedlings were cultivated under different N conditions (0.5 and 20 mM NO3–) in tissue culture for 25 days. Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). (D) Subcellular localization of the MeNPF4.5-EGFP fusion protein in tobacco leaf epidermal cells. From left to right, GFP fluorescence, chlorophyll fluorescence, bright field, and merged images are shown. Bars = 20 μm.

Expression of MeNPF4.5 Is Tissue Specific

To analyze the expression of MeNPF4.5 in response to different N levels, young cassava seedlings were grown in N-free (0 mM NO3–), low-N (0.5 mM NO3–), and full-N (20 mM NO3–) media. We found that the expression level of MeNPF4.5 in roots significantly decreased under N-free conditions. Compared with the N-free control where MeNPF4.5 was expressed at the lowest levels, MeNPF4.5 expression in roots was increased by 15.1-fold under low-N and 27.0-fold under full-N, which indicated that MeNPF4.5 expression was induced by NO3– (Figure 2A).

MeNPF4.5 expression in roots was also analyzed with a time-course experiment. After NO3– induction, the expression of MeNPF4.5 increased rapidly and reached a peak at 2 h. Expression then decreased gradually and stabilized at 6 h, but then decreased again, reaching the lowest level at 12 h before increasing again at 24 h (Figure 2B). Analysis of expression in different tissues showed that MeNPF4.5 was expressed in stems and leaves in addition to roots; and the expression level was highest in roots under both 0.5 and 20 mM NO3–, with expression levels 54.9- and 11.4-times higher than those in leaves, respectively (Figure 2C).

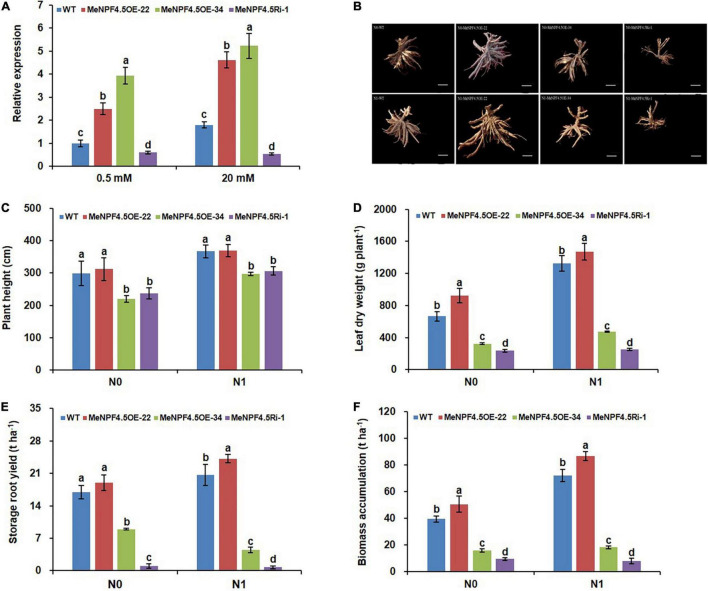

Identification of MeNPF4.5 Transgenic Cassava Plants

To investigate the function of MeNPF4.5, the 3 transgenic lines (overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34, and RNAi line MeNPF4.5 Ri-1) were constructed. Southern blot analysis verified that the exogenous MeNPF4.5 gene had been integrated into the genomes of MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 (Supplementary Figure 1), which confirmed that the overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 with a single copy of the transgenic construct and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 with two copies. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess the levels of MeNPF4.5 RNA in these lines. As shown in Figure 3A, the expression levels of MeNPF4.5 in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 were significantly higher than those in the WT under both N conditions, and the expression level in the Ri-1 line was decreased by 39.7 and 70.4% under low and normal N conditions, respectively. Therefore, these three lines were used for further analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Molecular identification and analysis of agronomic traits of WT and transgenic plants. (A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of MeNPF4.5 gene expression in the roots of WT and transgenic plants under 0.5 and 20 mM NO3–. MeNPF4.5 OE, MeNPF4.5 overexpression; MeNPF4.5 Ri, MeNPF4.5 RNA interference. The Actin gene was used as an internal control. (B–F) Agronomic traits of WT and transgenic plants grown in the field for 8 months under different N0 (0 kg ha–1) and N1 (125 kg ha–1) conditions. (B) Storage roots of cassava plants grown in the field. N0 treatment (upper panel), N1 treatment (lower panel); from left to right, WT, MeNPF4.5 OE-22, MeNPF4.5 OE-34, and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 images are shown. Bars = 10 cm. (C) Plant height (n = 10). (D) Leaf dry weight (n = 5). (E) Storage root yield (n = 5). (F) Biomass accumulation (n = 5). Values are means ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). N0, low-N treatment, 0 kg ha–1; N1, normal N treatment, 125 kg ha–1.

MeNPF4.5 Overexpression Enhances the Yield of Storage Roots

Lush foliage is the basis for healthy and high-yielding crops. Field evaluation of MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava showed that the two transgenic overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and the RNAi line MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 exhibited significant differences from WT in both the aerial and underground parts (Figure 3). Three of the four agronomic traits examined, namely leaf dry weight, storage root yield, and biomass accumulation, were significantly higher in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 than in WT under both low and normal N conditions, whereas these trait values were lower in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1. There was no significant difference in plant height between MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and WT, but both lines were significantly taller than MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 under both low and normal N conditions. These results demonstrated that NRT1.1 overexpression can improve plant growth under low or normal N conditions. However, no improvement in agronomic traits was observed for the MeNPF4.5 OE-34 line; all four traits examined were lower than those in WT and MeNPF4.5 OE-22, but higher than those in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1.

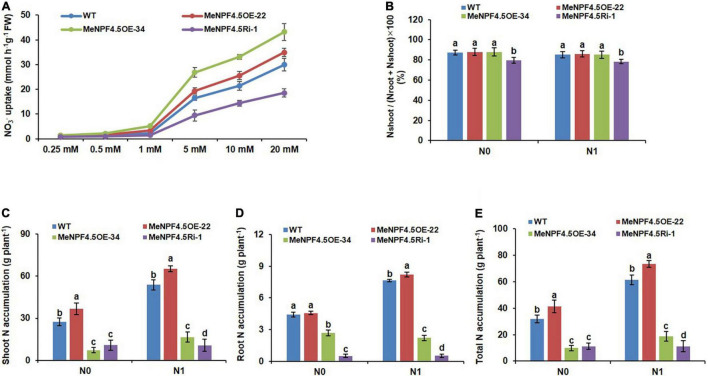

MeNPF4.5 Improves N Uptake, N Translocation, N Accumulation, and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

To determine the MeNPF4.5 function in NO3– uptake by roots, we measured the NO3– uptake of cassava roots. The results showed that the NO3– uptake of WT and transgenic cassava roots increased gradually with increasing of NO3– concentration. The NO3– uptake was significantly higher in overexpression lines (MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34) than those in the WT at relatively higher (1–20 mM) NO3– concentration. However, no significant difference was found at relatively lower (0.25 mM) NO3– concentrations. By contrast, the NO3– uptake was significantly lower in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 line than that in the WT at all tested NO3– concentrations (Figure 4A). Therefore, it seems that MeNPF4.5 is involved in the function of NO3– uptake.

FIGURE 4.

Nitrogen uptake, tanslocation and accumulation in WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants. (A) Root NO3– uptake in WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants. WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants grown in 20 mM KNO3 for 25 days and then deprived of N for 3 days. N-starved plant roots were then exposed to various NO3– concentrations for 6 h, uptake of NO3– were measured by disappearance of NO3– from the nutrient solution. (B) Nitrate translocation in WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants. (C–E) N accumulation in wild-type (WT) and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants harvested from the field. (C) Shoot N accumulation. (D) Root N accumulation. (E) Total N accumulation. Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). N0, low-N treatment, 0 kg ha–1; N1, normal N treatment, 125 kg ha–1.

Transport index was used as an indicator of NO3– translocation from roots to shoots (Figure 4B). Translocation of NO3– from roots to shoots between WT and transgenic lines, showing that the MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 plants have lower N enrichment in the shoots compared to those of WT and OE transgenic plants under both N conditions. However, N enrichment had no remarkable between OE transgenic plants (MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34) and WT under the N0 and N1 conditions, indicating that the translocation of NO3– to shoots is slower when MeNPF4.5 gene expression is suppressed, thus it can be seen that the MeNPF4.5 activity affects the NO3– translocation from roots to shoots.

As NRT1.1 is one of the NRT genes involved in NO3– uptake in roots, we analyzed the N accumulation of transgenic lines and WT plants. N accumulation is equal to the N content in each part of the plant multiplied by the biomass. As shown in Figures 4C–E, the amounts of shoot and whole-plant N accumulation in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 under low-N and normal N treatments were significantly higher than those in the WT, by 33.7% (N0) and 36.5% (N1) for shoots and by 29.5% (N0), 19.5% (N1) for the whole plant, but N accumulation was significantly lower in the MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 line than in the WT. The amounts of N accumulation in storage roots of MeNPF4.5OE-22 were similar to those in WT under low-N conditions, but higher than those in WT under normal N conditions, which verified that NRT1.1 was induced by high NO3– (≥0.50 mM). All these results show that NRT1.1 enhances NO3– uptake and accumulation in cassava.

The NUE of crops is related to the N uptake efficiency and N utilization efficiency, but their contributions to N efficiency remain controversial (Bogard et al., 2013). Our results indicated that there were significant differences in N utilization efficiency (NUtE), N recovery efficiency (NRE), and the partial factor productivity of N (PFPN) of the different transgenic cassava lines. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences in NUtE (under N0) and NRE between MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and WT, but NUtE (under N1) and PFPN of MeNPF4.5 OE-22 were significantly higher than those of the WT (by 7.6 and 16.8%, respectively). The NUtE under both N levels, NRE, and PFPN of MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 were significantly lower than those of the WT (reduced by 36.4, 130.1, and 94.7%, respectively). MeNPF4.5 OE-34 had a lower NUtE (under N1), NRE, and PFPN than WT, but NUtE under N0 conditions was significantly higher than that in the WT. These results indicated that the MeNPF4.5 gene expression level could severely affect the activity of NPF4.5 transporter in uptake and utilization of N under different N levels.

TABLE 1.

Differences in nitrogen uptake and utilization of wild-type and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava.

| Lines | N utilization efficiency |

N recovery efficiency (kg kg–1) | Partial factor productivity of applied N (kg kg–1) | |

| (kg kg–1) |

||||

| N0 | N1 | |||

| WT | 124.73 ± 5.93b | 109.72 ± 4.71b | 2.78 ± 0.15a | 166.34 ± 3.06b |

| MeNPF4.5 OE-22 | 127.15 ± 1.77b | 118.08 ± 1.58a | 2.68 ± 0.13a | 194.28 ± 1.24a |

| MeNPF4.5 OE-34 | 179.57 ± 9.42a | 99.29 ± 1.09c | 0.79 ± 0.04b | 36.31 ± 2.62c |

| MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 | 91.64 ± 3.27c | 75.30 ± 1.8d | 0.02 ± 0.00c | 6.12 ± 0.83d |

N0, low-N treatment, 0 kg ha–1; N1, normal N treatment, 125 kg ha–1. Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Values labeled with different letters represent significant differences between respective treatments by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

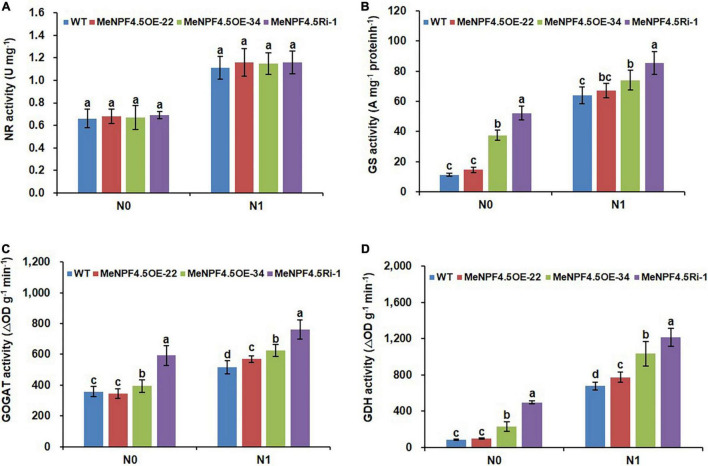

MeNPF4.5 Increases the Activities of Enzymes Related to N Metabolism in Cassava Leaves

The N absorbed by crop roots must be assimilated into organic matter through N metabolism enzymes before it can be used by the plant. The activity of key N metabolism enzymes can directly reflect the strength of N metabolism in crops (Andrews et al., 2004). The activities of enzymes involved in N metabolism, namely NR, GS, GOGAT, and GDH, were higher in WT and all the transgenic plants under the N1 treatment than under the N0 treatment, which showed that high N promoted the activities of these enzymes (Figure 5). The activities of all enzymes except for NR were higher in MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 than in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and the WT under both the N0 and N1 conditions; at the same time, the activities of these enzyme were significantly higher in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 than in WT under the N1 conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Activity of N metabolism enzymes. Activities of NR (A), GS (B), GOGAT (C), and GDH (D) in the leaves of WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava harvested from the field. Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). N0, low-N treatment, 0 kg ha–1; N1, normal N treatment, 125 kg ha–1.

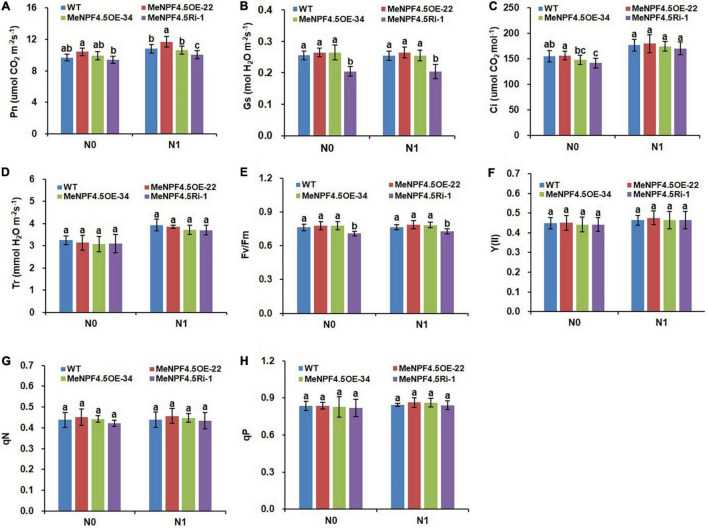

MeNPF4.5 Increases Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the physiological basis of crop growth and yield formation, and 90–95% of crop dry matter accumulation originates from photosynthetic products. As shown in Figures 6A–D, there was no significant difference in photosynthetic parameters, namely Gs, Ci, and Tr, between MeNPF4.5 OE-22, MeNPF4.5 OE-34, and WT under both N levels. The Pn of MeNPF4.5 OE-22 was 8.4% higher compared with that of WT under the N1 conditions. The Pn and Gs of MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 were significantly lower than those of WT under both N levels.

FIGURE 6.

Photosynthetic and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants. (A) Photosynthetic rate (Pn). (B) Stomatal conductance (Gs). (C) Intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). (D) Transpiration rate (Tr). (E) Fv/Fm. (F) Y(II). (G) qN. (H) qP. Values are the means of five biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a-d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). N0, low-N treatment, 0 kg ha–1; N1, normal N treatment, 125 kg ha–1.

Chlorophyll fluorescence is a direct indicator of plant physiology and reflects the photochemical process and its efficiency. As photosynthesis was altered by the MeNPF4.5 gene (Figures 6A–D), we wanted to evaluate the differences in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters between the transgenic lines and WT. The Fv/Fm values of the leaves of MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 plants were significantly lower compared with those of WT and OE transgenic plants under the N0 and N1 conditions (Figures 6E–H), but other chlorophyll fluorescence parameters did not significantly differ between the transgenic plants and WT.

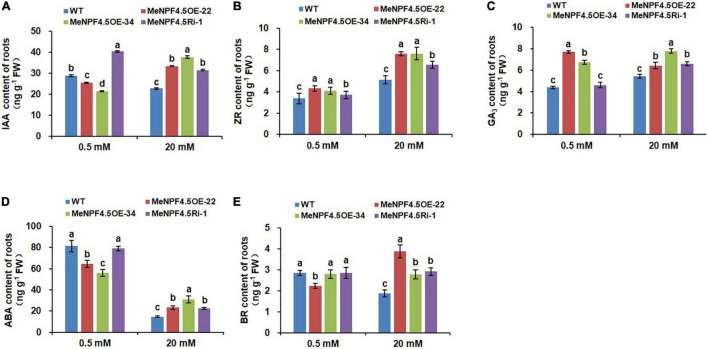

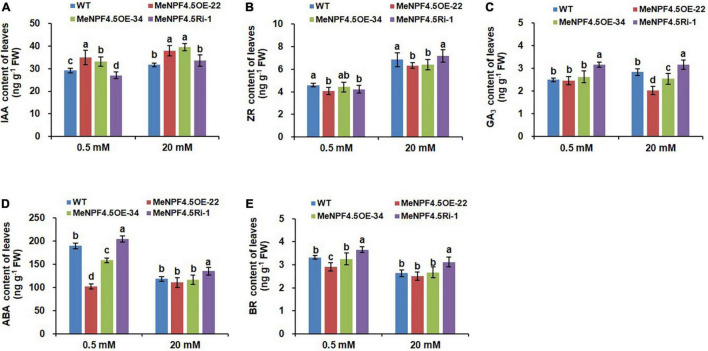

MeNPF4.5 Regulates Endogenous Hormone Levels in Cassava

Significant changes were also detected in endogenous hormones, namely indoleacetic acid (IAA), zeatin-riboside (ZR), gibberellic acid (GA3), abscisic acid (ABA), and brassinosteroid (BR), in the roots and leaves of transgenic cassava (Figures 7, 8). In roots, compared with WT, the levels of IAA were 11.8 and 25.8% lower in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and OE-34, respectively, and 39.9% higher in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 under low-N conditions (Figure 7). In contrast, under the full-N conditions the levels of IAA in transgenic plants (MeNPF4.5 OE-22, MeNPF4.5 OE-34, and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1) were 46.7, 65.2, and 38.2% higher than those in WT, respectively. For ZR and GA3, very similar patterns were observed in transgenic plants under both N levels. All the transgenic lines had a significantly higher ZR and GA3 contents than WT under both N conditions. Analysis of ABA revealed decreases of 20.5% in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and 31.0% in MeNPF4.5 OE-34 compared with WT. ABA levels in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 plants did not significantly differ from those in WT under low-N conditions. Under full-N conditions, the ABA content was higher compared with that in WT in all transgenic plants. Compared with WT plants, there was a 21.5% decrease of BR in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and no significant difference between WT and the MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 lines under low-N conditions. However, BR levels were higher in the three transgenic lines under full-N conditions. These results suggest that the MeNPF4.5 gene alters plant endogenous hormone levels in transgenic plants.

FIGURE 7.

Endogenous hormone levels in roots of WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants cultivated in tissue culture for 25 days. (A–E) contents of indoleacetic acid (IAA) (A), zeatin-riboside (ZR) (B), gibberellic acid (GA3) (C), abscisic acid (ABA) (D), and brassinolide (BR) (E). Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 8.

Endogenous hormone levels in leaves of WT and MeNPF4.5 transgenic cassava plants cultivated in tissue culture for 25 days. (A–E) Contents of indoleacetic acid (IAA) (A), zeatin-riboside (ZR) (B), gibberellic acid (GA3) (C), abscisic acid (ABA) (D), and brassinolide (BR) (E). Values are the means of three biological replicates ± SE. Lowercase letters above the bars (a–d) represent significant differences between treatments as determined by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

Analysis results on content of endogenous hormone in leaves showed that IAA in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 were higher than those in WT under both N conditions, and IAA levels in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 plants did not significantly differ from those in WT under full-N conditions but significantly lower than those in WT under low-N conditions (Figure 8). Compared with WT plants, there were significantly lower ZR contents in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 lines under low-N conditions. ZR levels in MeNPF4.5 OE-34 plants did not significantly differ from that in WT under low-N conditions. Under full-N conditions, the ZR content was lower compared with that in WT in the overexpression lines. Meanwhile, the overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 had a significantly lower GA3 contents than WT under full- N conditions. And the MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 lines had a significantly higher GA3 contents than those in WT under both N conditions. For ABA and BR, similar patterns were observed in transgenic plants under both N levels. ABA and BR levels in MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 plants was higher compared with those in WT and in the overexpression lines under both conditions. And the overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 had a significantly lower ABA and BR contents than those in WT under both N conditions. These results also suggest that the modulation of MeNPF4.5 gene expression alters plant endogenous hormone levels in transgenic plants.

Discussion

NRT1.1/NPF6.3 (CHL1) was the first NRT gene discovered in plants, and it also was found to function not only in NO3– uptake (Tsay, 1993) but also in NO3– translocation from roots to shoots (Léran et al., 2014). At present, research on NRT1.1 has mainly focused on the model plant Arabidopsis and the food crops rice (Hu et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2017; Wang Y. Y. et al., 2018) and wheat (Guo et al., 2014). Little information regarding this family is available in cassava, an important crop in much of the world. In this study, we investigated the spatiotemporal expression pattern and the function of the MeNPF4.5 gene in cassava. Our data clearly showed that MeNPF4.5 was barely detectable under N deficiency conditions, but its expression was maintained a high level under N sufficient conditions. This suggests that MeNPF4.5 expression could be induced by NO3– just as AtNRT1.1 is in Arabidopsis (Lejay et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1999). Once N-starved cassava plants were exposed to NO3–, MeNPF4.5 expression first increased and then decreased (Figure 2A). It can be seen that MeNPF4.5 responds to NO3– in the short term like many other plants NRT1.1 (Cárdenas Navarro et al., 1998; Okamoto et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007). In addition to being expressed in roots, AtNRT1.1 is also expressed in shoots, young leaves, and developing flower buds of Arabidopsis, but it is more strongly expressed in roots (Miller et al., 2007; Sakuraba et al., 2021). Consistent with the expression pattern of NRT1.1 in Arabidopsis, MeNPF4.5 is expressed in roots, stems, and leaves of cassava plants, and it is predominantly expressed in roots. We also conducted subcellular localization studies on the MeNPF4.5 protein and found that it was located on the plasma membrane, which was consistent with the findings of previous studies on NRT1.1 (Hu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2017).

Nitrate affects all aspects of plant physiology including metabolism, resource allocation, growth, and development, and its accumulation and translocation are critical to dry matter production. NRTs are not only involved in the uptake and transport of NO3– in roots, but also in the redistribution of NO3– among cells. The influence of the expression of NRTs on the N uptake and NUE of crops are important topics in breeding research. For example, Hu et al. (2015) demonstrated that overexpression of indica-type OsNRT1.1B can potentially improve the NUE of the japonica variety Zhonghua. Furthermore, a recent study showed that 35S promoter- driven expression of OsNRT1.1A improves the grain yield of transgenic rice plants (Wang W. et al., 2018). Overexpression of the OsNRT1.2 in the rice cultivar ‘Wuyunjing 7’ resulted in a biomass increase under a high concentration of NO3– (Ma et al., 2011). These results suggest an intimate relationship between the function of NRT1 and plant growth. To evaluate the effect of the MeNPF4.5 gene on cassava growth, we analyzed the yield and biomass of transgenic lines under two different N levels in a field test. Our results revealed differences between the overexpression lines and RNAi line; the yield and biomass of the overexpression lines were higher than those of the RNAi line. Compared with the WT, the growth of cassava was promoted in the overexpression line MeNPF4.5 OE-22 under both low and normal N conditions, while growth of the RNAi line MeNPF4.5Ri-1 was inhibited (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies and shows that enhanced MeNPF4.5 expression could improve growth in cassava under both low and normal N conditions. However, another MeNPF4.5 overexpression line, MeNPF4.5 OE-34, exhibited inhibited growth compared with WT and MeNPF4.5 OE-22, although its growth was superior to that of MeNPF4.5Ri-1. This might be related to the high expression of MeNPF4.5 in this line, which may affect the balance between N uptake and utilization; or maybe MeNPF4.5 OE-34 has two copy of the transgenic construct, which might lead to the silence of target gene and thus affect plant growth (Vaucheret et al., 1998; Tenea et al., 2008; Ahlawat et al., 2014).

Nitrogen use efficiency can be simply defined as the yield of grain per unit of N available in the soil. NUE depends on N uptake efficiency and internal utilization efficiency, and N uptake-and-utilization efficiency reflects the capacity of crops to absorb N and transport it to the organs (Moll et al., 1982; Chen and Ma, 2015). Therefore, here we examined the association between N uptake, translocation, NUtE, and growth. OsNRT1.1B was reported to increase the NUtE of rice by 30% (Duan and Zhang, 2015; Hu et al., 2015), and Chen and Ma (2015) reported that OsNRT1.1B improves NUE in rice by enhancing root NO3– uptake. Here we found that MeNPF4.5 enhanced N uptake, translocation, and accumulation in cassava; NUtE, NRE, and PFPN were improved in MeNPF4.5 overexpressing plants but were significantly lower in the MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 line compared with WT (Table 1). It is inferred that the higher yields of the overexpression lines MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and MeNPF4.5 OE-34 may be due to their high N uptake and transport capabilities, while the yield of MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 decreased because of its reduced N uptake and allocation.

N is absorbed by cassava in the form of NO3–, and then it needs to be assimilated mainly in shoot part into organic N through the catalytic action of several enzymes. Studies have found that when NO3– addition to N-starved seedlings, all genes known to be directly required for NO3– assimilation were strongly induced, including N metabolism enzyme gene (Gowri et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2003; Scheible et al., 2004). Hu et al. (2009) also confirmed that NO3– assimilation genes are regulated by NO3–, and these genes are expressed at low levels in the absence of NO3– and are rapidly induced in its presence (priming effect). Much evidence suggests that NR and GS are the key enzymes for N assimilation (Thomsen et al., 2014). For most plants, there is a positive correlation between the amount of NO3– absorbed by the roots from the soil and NR activity (Andrews et al., 2004). Meanwhile, GS enzyme activity and stability are positively correlated with substrate abundance (Andrews et al., 2004). Other enzymes responsible for N assimilation in addition to NR and GS, such as GOGAT, GDH, and asparagine synthetase, have also been reported to play important roles in N metabolism and improvement of NUE in plants (Ameziane et al., 2000; Wong et al., 2004; Yamaya and Kusano, 2014). In this study, we found that the activity of nitrogen metabolism enzymes in the same line under N1 level was higher than that under N0 level, indicating that N metabolism enzyme were induced by NO3–. The GS, GOGAT, and GDH activities in MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 were higher than those in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 and the WT under both the N0 and N1 conditions, but there was no significant difference in NR activity. Although the activities of these enzymes were higher in MeNPF4.5 OE-34 and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 than in the WT, the growth of these plants was inhibited and N accumulation was lower. Studies have shown that compared with the WT, transgenic rice that overexpress GS1 (Tabuchi et al., 2007) show no difference in growth phenotype and have lower yields. Transgenic tobacco plants that overexpress GS2 show limited growth and leaf yellowing (Thomsen et al., 2014). Some studies suggest that these phenomena may be the result of feedback inhibition of nitrogen metabolites (Vincentz and Caboche, 1991). The results of this study may also related to this phenomenon.

Previous studies found that there is a significant positive correlation between photosynthesis and crop yield and NUE (Zhang et al., 2017). However, some studies have pointed out that the substantial increase in crop yield achieved in the past few decades has not been accompanied by a significant increase in leaf Pn. The yield gain is mainly attributed to an increase in leaf area index and biological yield (Sharma-Natu and Ghildiyal, 2005). In this study, the leaf dry weight and Pn in MeNPF4.5 OE-22 were significantly higher compared with those in WT, while these two traits were significantly lower in the RNAi line. The Fv/Fm values in the RNAi line were also lower. Therefore, it is speculated that the difference in leaf area index and photosynthetic parameters may underlie the difference in NUE and yield between MeNPF4.5 OE-22 plants and MeNPF4.5 Ri-1 and WT plants.

Hormones play an important role in regulating various metabolic, growth, and development processes, and maintaining a dynamic balance under normal physiological conditions. Lots of plant hormones are transported by some NRT proteins and conversely regulate NRT gene expression (Zhao et al., 2021). NRT1.1 in roots can transport NO3– and auxin, but preferentially transports NO3– (Krouk et al., 2010; Bouguyon et al., 2015). Hormone metabolism appears transcriptional reprogramming and sensing as one of the early response to NO3– addition (Scheible et al., 2004), while higher supply of NO3– decreased IAA concentrations in phloem exudates, which affected root growth (Bhalerao et al., 2002; Tian et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010). Krouk et al. (2010) propose that NRT1.1 represses lateral root growth at low NO3– availability by promoting basipetal auxin transport out of these roots. In this study, we had the similar results, the IAA content in roots of the two overexpression lines was significantly lower compared with that of WT under low-N conditions, was higher in roots of RNAi line, which might be resulted from MeNPF4.5 promoting basipetal auxin transport and lowering auxin accumulation in the roots in OE plants, while the transport ability was inhibited in RNAi lines. Under full-N conditions, it was speculated that MeNPF4.5 performed the NO3– transport function, which could lead to higher IAA content in roots of the transgenic lines than in that of WT. In addition, our results showed that the content of IAA in leaves of overexpressed lines remained at a high level under both N levels, which may be related with a higher translocation of N toward the aerial parts associated with more production of IAA. Previous studies found that the change of IAA levels in the root was closely related to NO3– mediated root growth, however, the latter process could not be explained exclusively by the former, due to NO3– has a comprehensive effect on other phytohormones, such as cytokinin (Beck, 1996; Takei et al., 2001) and ethylene (Singh et al., 2000), which also exert significant effects on root development. The changes of other hormones contents (ZR, GA3, ABA, and BR) were also detected in roots and leaves of transgenic plants and WT under two N levels, in previous report, Tian et al. (2005) also discovered that cytokinin concentrations in roots enhanced with increasing NO3– supply. Therefore, it is supposed that IAA might synergistically interact with ZR, GA3, ABA, and BR to affect the growth of cassava plants. And further study is required to elucidate the interaction among these hormones on NO3– mediated cassava growth.

In summary, MeNPF4.5 is mainly expressed in cassava roots, and its expression is induced by NO3–. Overexpressing MeNPF4.5 in cassava promoted growth and improved the NUE and yield. The main reasons for these effects may be increased photosynthesis and N metabolism enzyme activity. Down-regulation of MeNPF4.5 expression resulted in inhibition of cassava growth and reduction of NUE, causing a decrease in biomass and yield. Overall, our study reveals the role of MeNPF4.5 in N uptake and utilization, which has not been previously reported, and shows that this NRT may have potential breeding value.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

QL and QM prepared the manuscript. MD and QL conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. BH designed the experiments. MG and PZ supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We highly appreciate technical support from Xiaoguang Duan, who is a research scientist in the Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2018GXNSFDA281056 and 2016GXNSFBA380220) and China Agriculture Research System.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.866855/full#supplementary-material

Southern blotting analysis of MeNPF4.5 transgenic plants. WT, wild type; M, marker; OE22-OE34: MeNPF4.5 overexpress transgenic plants. The probes were HPT in left three samples and MeNPF4.5 in right three samples, and the restriction endinuclease was Hind III.

References

- Ahlawat S., Saxena P., Alam P., Wajid S., Abdin M. Z. (2014). Modulation of artemisinin biosynthesis by elicitors, inhibitor, and precursor in hairy root cultures of Artemisia Annua L. J. Plant Interact. 9 811–824. 10.1080/17429145.2014.949885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ameziane R., Bernhard K., Lightfoot D. (2000). Expression of the bacterial gdhA gene encoding a NADPH glutamate dehydrogenase in tobacco affects plant growth and development. Plant Soil 221 47–57. 10.1023/A:1004794000267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M., Lea P. J., Raven J. A., Lindsey K. (2004). Can genetic manipulation of plant nitrogen assimilation enzymes result in increased crop yield and greater N-use efficiency? An assessment. Ann. Appl. Biol. 145 25–40. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00356.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck E. H. (1996). Regulation of shoot/root ratio by cytokinins from roots in Urtica dioica: opinion. Plant Soil 185 3–12. 10.1007/bf02257560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalerao R. P., Eklof J., Ljung K., Marchant A., Bennett M., Sandberg È. (2002). Shoot-derived auxin is essential for early lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J 29 325–332. 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogard M., Allard V., Martre P., Heumez E., Snape J. W., Orford S., et al. (2013). Identifying wheat genomic regions for improving grain protein concentration independently of grain yield using multiple inter-related populations. Mol. Breed. 31 587–599. 10.1007/s11032-012-9817-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouguyon E., Brun F., Meynard D., Kubeš M., Pervent M., Leran S., et al. (2015). Multiple mechanisms of nitrate sensing by Arabidopsis nitrate transceptor NRT1.1. Nat. Plants 1 2–9. 10.1038/nplants.2015.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas Navarro R., Adamowicz S., Robin P. (1998). Modelling diurnal nitrate uptake in young tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) plants using a homoeostatic model. Acta Hortic. 456 247–253. 10.17660/actahortic.1998.456.28 34854763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. C., Ma J. F. (2015). Improving nitrogen use efficiency in rice through enhancing root nitrate uptake mediated by a nitrate transporter. NRT1.1B. J. Genet. Genomics 42 463–465. 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. D., Zhang H. M. (2015). A single SNP in NRT1.1B has a major impact on nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Sci. China Life Sci. 58 827–828. 10.1007/s11427-015-4907-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Naz M., Fan X., Xuan W., Miller A. J., Xu G. (2017). Plant nitrate transporters: from gene function to application. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2463–2475. 10.1093/jxb/erx011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T., King G. M., Blackburn T. H. (2012). Transport mechanisms. Bact. Biogeochem. 3 35–47. 10.1016/b978-0-12-415836-8.00002-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Wang Y., Chen G., Zhang A., Yang S., Shang L., et al. (2019). The indica nitrate reductase gene OsNR2 allele enhances rice yield potential and nitrogen use efficiency. Nat. Commun 10:5207. 10.1038/s41467-019-13110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowri G., Kenis J. D., Ingemarsson B., Redinbaugh M. G., Campbell W. H. (1992). Nitrate reductase transcript is expressed in the primary response of maize to environmental nitrate. Plant Mol. Biol. 18 55–64. 10.1007/BF00018456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Xuan H., Yang Y., Wang L., Wei L., Wang Y., et al. (2014). Transcription analysis of genes encoding the wheat root transporter NRT1 and NRT2 families during nitrogen starvation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 33 837–848. 10.1007/s00344-014-9435-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. H., Lin S. H., Hu H. C., Tsay Y. F. (2009). CHL1 Functions as a Nitrate Sensor in Plants. Cell 138 1184–1194. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Wang W., Ou S., Tang J., Li H., Che R., et al. (2015). Variation in NRT1.1B contributes to nitrate-use divergence between rice subspecies. Nat. Genet. 47 834–838. 10.1038/ng.3337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. C., Wang Y. Y., Tsay Y. F. (2009). AtCIPK8, a CBL-interacting protein kinase, regulates the low-affinity phase of the primary nitrate response. Plant J. 57 264–278. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Wang X., Wang G. (2015). Synthesis and characterization of copolymers with the same proportions of polystyrene and poly(ethylene oxide) compositions but different connection sequence by the efficient Williamson reaction. Polym. Int. 64 1202–1208. 10.1002/pi.4891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., Suh S. J., Guan C., Tsay Y. F., Moran N., Oh C. J., et al. (2004). A nodule-specific dicarboxylate transporter from alder is a member of the peptide transporter family. Plant Physiol. 134 969–978. 10.1104/pp.103.032102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L., Liang Q., Jiang Q., Yao Y., Dong M., He B., et al. (2020). Screening of diverse cassava genotypes based on nitrogen uptake efficiency and yield. J. Integr. Agric. 19 965–974. 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62746-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno Y., Hanada A., Chiba Y., Ichikawa T., Nakazawa M., Matsui M., et al. (2012). Identification of an abscisic acid transporter by functional screening using the receptor complex as a sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 9653–9658. 10.1073/pnas.1203567109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova N. Y., Thor K., Gubler A., Meier S., Dietrich D., Weichert A., et al. (2008). AtPTR1 and AtPTR5 transport dipeptides in planta. Plant Physiol. 148 856–869. 10.1104/pp.108.123844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G., Lacombe B., Bielach A., Perrine-Walker F., Malinska K., Mounier E., et al. (2010). Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev. Cell 18 927–937. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou M. C., Leskovar D. I., Colla G., Rouphael Y. (2018). Watermelon and melon fruit quality: the genotypic and agro-environmental factors implicated. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 234 393–408. 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.01.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lassaletta L., Billen G., Grizzetti B., Anglade J., Garnier J. (2014). 50 year trends in nitrogen use efficiency of world cropping systems: the relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ. Res. Lett 9:105011. 10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lejay L., Tillard P., Lepetit M., Olive F. D., Filleur S., Plantes Â. (1999). Molecular and functional regulation of two NO 3 ± uptake systems by N- and C-status of arabidopsis plants. Plant J 18 509–519. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léran S., Muños S., Brachet C., Tillard P., Gojon A., Lacombe B. (2013). Arabidopsis NRT1.1 is a bidirectional transporter involved in root-to-shoot nitrate translocation. Mol. Plant 6 1984–1987. 10.1093/mp/sst068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léran S., Varala K., Boyer J. C., Chiurazzi M., Crawford N., Daniel-Vedele F., et al. (2014). A unified nomenclature of nitrate transporter 1/peptide transporter family members in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 19 5–9. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Hu B., Chu C. (2017). Nitrogen use efficiency in crops: lessons from Arabidopsis and rice. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2477–2488. 10.1093/jxb/erx101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li J., Yan Y., Liu W., Zhang W., Gao L., et al. (2018). Knock-down of CsNRT2.1, a cucumber nitrate transporter, reduces nitrate uptake, root length, and lateral root number at low external nitrate concentration. Front. Plant Sci. 9:722. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. H., Huang C. Y., Tsay Y. F. (1999). CHL1 is a dual-affinity nitrate transporter of Arabidopsis involved in multiple phases of nitrate uptake. Plant Cell 11 865–874. 10.1105/tpc.11.5.865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., An X., Cheng L., Chen F., Bao J., Yuan L., et al. (2010). Auxin transport in maize roots in response to localized nitrate supply. Ann. Bot 106 1019–1026. 10.1093/aob/mcq202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Feng H., Huang D., Song M., Fan X., Xu G. (2015). Two short sequences in OsNAR2.1 promoter are necessary for fully activating the nitrate induced gene expression in rice roots. Sci. Rep. 5 1–10. 10.1038/srep11950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Fan X., Xu G. (2011). Responses of rice plant of wuyuanjing 7 to nitrate as affected by over-expression of OsNRT1.2. Chinese J. Rice Sci. 4 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Maghiaoui A., Gojon A., Bach L. (2021). NRT1.1-centered nitrate signaling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 71 6226–6237. 10.1093/JXB/ERAA361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. J., Fan X., Orsel M., Smith S. J., Wells D. M. (2007). Nitrate transport and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 58 2297–2306. 10.1093/jxb/erm066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra B. K., Srivastava J. P., Lal J. P., Sheshshayee M. S. (2016). Physiological and biochemical adaptations in lentil genotypes under drought stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 63 695–708. 10.1134/S1021443716040117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R. H., Kamprath E. J., Jackson W. A. (1982). Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of nitrogen utilization 1. Agron. J. 74 562–564. 10.2134/agronj1982.00021962007400030037x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15 473–497. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M., Vidmar J. J., Glass A. D. M. (2003). Regulation of NRT1 and NRT2 gene families of Arabidopsis thaliana: Responses to nitrate provision. Plant Cell Physiol. 44 304–317. 10.1093/pcp/pcg036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S., Buresh R. J., Huang J., Yang J., Zou Y., Zhong X., et al. (2006). Strategies for overcoming low agronomic nitrogen use efficiency in irrigated rice systems in China. F. Crop. Res. 96 37–47. 10.1016/j.fcr.2005.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remans T., Nacry P., Pervent M., Filleur S., Diatloff E., Mounier E., et al. (2006). The Arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signaling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 19206–19211. 10.1073/pnas.0605275103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren N., Chen X., Xia Y., Bai X., Jiang X., Zhou Y. (2019). Cloning and expression analysis of MeNRT2.5 gene in cassava. Tropical. biol. 10 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba Y., Chaganzhana, Mabuchi A., Iba K., Yanagisawa S. (2021). Enhanced NRT1.1/NPF6.3 expression in shoots improves growth under nitrogen deficiency stress in Arabidopsis. Commun. Biol. 4 1–14. 10.1038/s42003-021-01775-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma-Natu P., Ghildiyal M. C. (2005). Potential targets for improving photosynthesis and crop yield. Cur. Sci. India. 88 1918–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Scheible W. R., Morcuende R., Czechowski T., Fritz C., Osuna D., Palacios-Rojas N., et al. (2004). Genome-wide reprogramming of primary and secondary metabolism, protein synthesis, cellular growth processes, and the regulatory infrastructure of Arabidopsis in response to nitrogen. Plant Physiol. 136 2483–2499. 10.1104/pp.104.047019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Maan A., Singh B., Sheokand S., Vrat D., Sheoran A. (2000). Ethylene evolution and antioxidant defence mechanism in Cicer arietinum roots in the presence of nitrate and aminoethoxyvinylglycine. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38 709–715. 10.1016/s0981-9428(00)01174-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M., Georgescu M. N., Takahashi M. (2007). A nitrite transporter associated with nitrite uptake by higher plant chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 1022–1035. 10.1093/pcp/pcm073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi M., Abiko T., Yamaya T. (2007). Assimilation of ammonium ions and reutilization of nitrogen in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Exp. Bot. 58 2319–2327. 10.1093/jxb/erm016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei K., Sakakibara H., Taniguchi M., Sugiyama T. (2001). Nitrogen-dependent accumulation of cytokinins in root and the translocation to leaf: Implication of cytokinin species that induces gene expression of maize response regulator. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 85–93. 10.1093/pcp/pce009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal I., Zhang Y., Jørgensen M. E., Pisanty O., Barbosa I. C. R., Zourelidou M., et al. (2016). The Arabidopsis NPF3 protein is a GA transporter. Nat. Commun 7:11486. 10.1038/ncomms11486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenea G. N., Calin A., Gavrila L., Cucu N. (2008). Manipulation of root biomass and biosynthetic potential of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. plants by Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated transformation. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 13 3922–3932. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen H. C., Eriksson D., Møller I. S., Schjoerring J. K. (2014). Cytosolic glutamine synthetase: a target for improvement of crop nitrogen use efficiency? Trends Plant Sci. 19 656–663. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q., Chen F., Zhang F., Mi G. (2005). Possible involvement of cytokinin in nitrate-mediated root growth in maize. Plant and Soil 277 185–196. 10.1007/s11104-005-6837-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q., Chen F., Liu J., Zhang F., Mi G. (2008). Inhibition of maize root growth by high nitrate supply is correlated with reduced IAA levels in roots. J Plant Physiol 165 942–951. 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay Y. F. (1993). The herbicide sensitivity gene chl1 of arabidopsis encodes a nitrate-inducible nitrate transporter. Cell 72, 705–713. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90399-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga S. F., Ibarra-Henríquez C., Fredes I., Álvarez J. M., Gutiérrez R. A. (2017). Nitrate signaling and early responses in Arabidopsis roots. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2541–2551. 10.1093/jxb/erx041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H., Béclin C., Elmayan T., Feuerbach F., Godon C., Morel J. B., et al. (1998). Transgene-induced gene silencing in plants. Plant J. 16 651–659. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren H., Alder A., Zhang P., Gruissem W. (2009). Dose-dependent RNAi-mediated geminivirus resistance in the tropical root crop cassava. Plant Mol. Biol. 70 265–272. 10.1007/s11103-009-9472-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentz M., Caboche M. (1991). Constitutive expression of nitrate reductase allows normal growth and development of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia plants. EMBO J. 10 1027–1035. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08041.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Okamoto M., Xing X., Crawford N. M. (2003). Microarray analysis of the nitrate response in Arabidopsis roots and shoots reveals over 1,000 rapidly responding genes and new linkages to glucose, trehalose-6-phosphate, iron, and sulfate metabolism. Plant Physiol. 132 556–567. 10.1104/pp.103.021253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Xing X., Crawford N. (2007). Nitrite acts as a transcriptome signal at micromolar concentrations in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 145 1735–1745. 10.1104/pp.107.108944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Hu B., Yuan D., Liu Y., Che R., Hu Y., et al. (2018). Expression of the nitrate transporter gene OsNRT1.1A/OsNPF6.3 confers high yield and early maturation in rice. Plant Cell 30 638–651. 10.1105/tpc.17.00809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y., Cheng Y. H., Chen K. E., Tsay Y. F. (2018). Nitrate transport, signaling, and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 69 85–122. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y., Hsu P. K., Tsay Y. F. (2012). Erratum to: “Uptake, allocation and signaling of nitrate”. Trends Plant Sci. 17:624. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H. K., Chan H. K., Coruzzi G. M., Lam H. M. (2004). Correlation of ASN2 gene expression with ammonium metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134 332–338. 10.1104/pp.103.033126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. H., Fan X. R., Miller A. J. (2012). Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 153–182. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaya T., Kusano M. (2014). Evidence supporting distinct functions of three cytosolic glutamine synthetases and two NADH-glutamate synthases in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 65 5519–5525. 10.1093/jxb/eru103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Potrykus I., Puonti-Kaerlas J. (2000). Efficient production of transgenic cassava using negative and positive selection. Transgenic Res. 9 405–415. 10.1023/A:1026509017142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang J., Gong S., Xu D., Sui J. (2017). Nitrogen fertigation effect on photosynthesis, grain yield and water use efficiency of winter wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 179 277–287. 10.1016/j.agwat.2016.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Chen P., Liu P., Song Y., Zhang D. (2021). Genetic effects and expression patterns of the nitrate transporter (NRT) gene family in populus tomentosa. Front. Plant Sci. 12:661635. 10.3389/fpls.2021.661635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Geng X., Bi W., Xu Q., Sun J., Huang Y., et al. (2017). Recombination between dep1 and NRT1.1B under japonica and indica genetic backgrounds to improve grain yield in rice. Euphytica 213 1–9. 10.1007/s10681-017-2038-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. J., Theodoulou F. L., Muldin I., Ingemarsson B., Miller A. J. (1998). Cloning and functional characterization of a Brassica napus transporter that is able to transport nitrate and histidine. J. Biol. Chem. 273 12017–12023. 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang D., Jiang D., Liu L., Huang Y. (2011). Assessment of bioenergy potential on marginal land in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15 1050–1056. 10.1016/j.rser.2010.11.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Qi D., Sun J., Zheng X., Peng M. (2019). Expression of the cassava nitrate transporter NRT2.1 enables Arabidopsis low nitrate tolerance. J. Genet. 98:74. 10.1007/s12041-019-1127-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Southern blotting analysis of MeNPF4.5 transgenic plants. WT, wild type; M, marker; OE22-OE34: MeNPF4.5 overexpress transgenic plants. The probes were HPT in left three samples and MeNPF4.5 in right three samples, and the restriction endinuclease was Hind III.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.