Abstract

The polysaccharide of Atractylodes macrocephala koidz (PAMK) has been proved to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immunity promoting effects. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have also been shown to participate in the regulation of immune function by negatively regulating the expression of target genes. However, little is known about how PAMK alleviates the immunosuppression via the miRNA pathway in geese. The aim of this study is to evaluate the influence of PAMK on immunosuppression. Magang geese (1 day old, n = 200) were randomly divided into groups, namely, the control group (normal feeding), PAMK (fed 400 mg kg−1 PAMK), CTX (injected 40 mg kg−1 BW cyclophosphamide), and CTX + PAMK (40 mg kg−1 BW cyclophosphamide + 400 mg kg−1 PAMK) groups. Thymus development was examined by the thymus index, transmission electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. The T cell proliferation rate was stimulated by phytoagglutinin (PHA), and T cell activation related genes (CD28, CD96, MHC-II), and IL-2 levels in serum were detected. Differentially expressed miRNAs of geese to regulate T cell activation were found by miRNA sequencing technologies. The results showed that PAMK could alleviate thymus damage and the decrease in the T lymphocyte proliferation rate, T cell activation, and IL-2 levels that were induced by CTX. MiRNA sequencing found that the combination of PAMK and CTX significantly promoted T cell activation via upregulation of novel_mir2 (P < 0.05), which inhibited cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) expressions, thereby promoting the TCR-NFAT signaling pathway. It can be concluded that PAMK, through novel_mir2 targeting of CTLA4 to upregulate TCR pathway, finally alleviated immunosuppression induced by CTX in geese.

The polysaccharide of Atractylodes macrocephala koidz (PAMK) has been proved to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immunity promoting effects.

Introduction

Many polysaccharides from Chinese herbal medicine have been shown to promote immune function as well as alleviate cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression.1–3 The polysaccharide of Atractylodes macrocephala koidz (PAMK) is an immune enhancer that improves immune function and has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.4,5 PAMK modulates immune function by promoting immune organ development and immune cell activation, as well as increasing lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine secretion.6–11 Recent research also revealed that another important biological effect of PAMK is to resist heat stress and maintain the immune function at a stable level.5,12,13 However, there has been no report about the effects of PAMK on alleviating immunosuppression.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression after transcription by selectively degrading mRNA or inhibiting translation. Studies have shown that many miRNAs are involved in the regulation of immune functions, and some of them are cell-type specific.14 MiR-15b, miR-181, miR-31, miR-126, miR-155, and miR146a are involved in the regulation of T cell activation and proliferation, secretion of cytokines, and other related functions.15–18 MiRNAs regulate T cell activation mainly by targeting different genes in the T cell receptor (TCR) pathway. It was reported that miR-181 targeted multiple phosphatases, miR-21 targeted activator protein-1 (AP-1) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), miR-155 and miR-429 targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) in the TCR pathway and finally changed T cell activation.17,19–22

Although it has been confirmed that miRNAs are involved in regulating immune function, the role of miRNAs in the mechanism of PAMK that promotes immune function, especially the alleviation of immunosuppression in geese, has not been clarified. In this study, an immunosuppressed model of geese was constructed by injecting cyclophosphamide (CTX), and the effects of PAMK on the alleviation of immunosuppression were studied in the combination of PAMK and CTX. We also focus on the difference in miRNAs between CTX and CTX + PAMK to find out the mechanisms of PAMK in the alleviation of immunosuppression.

Materials and methods

Animals

One-day-old geese (Anser cygnoides) were purchased from Guangdong Qingyuan Jinyufeng Goose Co. Ltd., which is a professional goose hatching company, and were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment. The geese had free access to food (including the same amount of vegetables) and water, were treated humanely, and the experiments received prior ethical approval in accordance with Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, and under the approved protocol number SRM-11.

Reagents

PAMK (purity 70%) was purchased from Tianyuan (Xi'an, China), diluted with water and sprayed on the feed according to the concentration of 400 mg kg−1. Cyclophosphamide (Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceutical, China), was dissolved in physiological saline and intraperitoneally injected in the geese at a concentration of 40 mg kg−1 BW. Lymphocyte separation fluid was purchased from Tianjin Haoyang Biological Manufacturers. Phytoagglutinin (PHA; Sigma, USA), as the T cell mitogen, was dissolved in 15 μg mL−1 with RPMI-1640. Calf serum (Corning, USA) was used to culture lymphocytes and an MTS Kit (Promega, USA) was used to detect the T cell proliferation rate. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, China) and a first-strand complementary (cDNA) kit (Invitrogen, China) were used for quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Immunosuppression induction and treatment

Two hundred geese (1 day-old, with half of them being male and half female) were randomly divided into four groups (n = 50 per group). The control and CTX groups were fed with normal diets, whereas the PAMK and CTX + PAMK groups were fed with 400 mg kg−1 PAMK. In addition, the control and PAMK groups were injected with 0.5 mL saline, while the CTX and CTX + PAMK groups were injected with 40 mg kg−1 BW CTX per day at 12–14 days of age to construct immunosuppression models. Thymus and blood were collected at 28 days of age. All organs were immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until used. IL-2 levels in serum were detected by ELISA.

Thymus index assay

The weights of the thymuses were measured immediately after the geese were slaughtered. The thymus index was calculated as the ratio of the thymus weight (g) to body weight (kg).

Ultrastructural observation

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The thymus was divided into small blocks of about 1 mm3 and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C. Ultra-thin sections of 50–70 nm thickness were prepared and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate following the conventional protocol. The material was observed using TEM (JEM-1400, Japan).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The thymus was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, as above, for 2 hours, and observed using SEM (Hitachi S3000N, Japan).

T cell proliferation assay

Thymuses of the four groups were collected and ground separately into cell suspensions, which were then filtered using a 40 μm cell sieve. Lymphocytes were isolated using lymphocyte separation fluid and collected. The lymphocytes were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in RPMI-1640 complete medium containing 10% calf serum. Trypan blue staining requires more than 98% cell viability for each group. The cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells per mL. PHA was added to the culture medium to activate T cell proliferation. After culturing for 44 hours, an MTS Kit was used to detect the T cell proliferation rate. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Biotek Epoch, USA). The ratio of the absorbance of cells treated with PHA to the absorbance without PHA was used as an indicator of the T cell proliferation rate.

Serum IL-2 assay

Venous blood was collected to separate the serum. The levels of IL-2 secreted by activated T cells in the serum were measured using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Quantitative real-time PCR assay

Specific primers for miRNAs and target genes were designed (Table 1). U6 was used to normalize the miRNAs and β-actin was used to normalize the genes. The procedure used for qPCR was similar to that used by Yao.23 Total RNA was isolated from individual thymuses using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand complementary (cDNA) was synthesized using oligo dT primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase, according to the manufacturer's instructions. QPCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7500 detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The PCR procedure steps included 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C for 30 s.

Primer sequences of mRNA for qPCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| MHC-II | F: CCGAGATCGAGGTGAAGTG |

| R: GGGTGCTTTCCAGCATCA | |

| CD28 | F: ATCTGGACACCCCTCAACAT |

| R: TGAACTGGATGCTGTAGGAA | |

| CD96 | F: CCAGAGAGGATCCGGAAGAG |

| R: ATGCGTTCCTCACAATGCA | |

| CTLA4 | F: CCCTAGCCGAAACAATGTG |

| R: GCTCCATCTTGCAGACATAA | |

| CD247 | F: CGTGGGCACAGAGATGAATA |

| R: CCGTCTCTGATGGTCTCCTT | |

| NFAT | F: GCCAAGCTCTACCACCAATG |

| R: CAGCACTTGGGCAGTGGTAT | |

| β-Actin | F: GCACCCAGCACGATGAAAAT |

| R: GACAATGGAGGGTCCGGATT |

Sequencing and differential expression analysis of miRNA

Thymuses were collected for miRNA sequencing. Each group possessed three biological replicates. All samples from the geese were sent to the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) for miRNA sequencing and were sequenced using Hiseq technology, referring to Anser cygnoides. The results were filtered to obtain clean tags, which were mapped to sRNA databases such as miRBase, Rfam, siRNA, piRNA, small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) to annotate miRNAs, piRNAs, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and other non-coding RNA (ncRNA) sequences, and then aligned to exons and introns of mRNAs to screen and remove degraded fragments. To obtain unique small RNAs that mapped to only one annotation, the following priority rules were used: MiRNA > piRNA > snoRNA > Rfam > other sRNA. MiRDeep2 was used to identify the known and predict novel miRNAs. Small RNAs with reads less than 100 were discarded, and the miRNA level was calculated using transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) values (TPM = (miRNA total reads/total clean reads) × 106), which eliminates the influence of sequencing discrepancy on the calculation of small RNA expression.

To validate the effects of PAMK under the treatment of CTX, the differentially expressed miRNAs (|log2(fold change)| > 1 and P-value ≤ 0.05) between the control group and PAMK group (control vs. PAMK), and between the CTX and CTX + PAMK groups (CTX vs. CTX + PAMK) were identified. To identify the possible targets of the miRNAs, RNAhybrid, miRanda, and TargetScan software were used. To understand the functions of the predicted target genes, gene ontology (GO) and KEGG enrichment analyses on differentially expressed miRNAs were performed using a hypergeometric test with a false discovery rate ≤0.05. The differentially expressed miRNAs of control vs. PAMK and CTX vs. CTX + PAMK were mapped to KEGG and the most significant changed pathway related to T cell activation was identified. In addition, detection and interaction analyses of differentially expressed miRNAs and target mRNAs in this pathway were performed based on the target prediction, functional annotation, and the negative regulatory mechanism of mRNAs and miRNAs.

Verification of miRNAs and target genes

Specific primers for the miRNAs and target genes were designed (Table 2). The qPCR process was the same as that detailed above.

Primer sequences of miRNA for qPCR.

| miRNA | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| novel_mir457 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGAGGATGCAGGCAGGGAGG |

| novel_mir19 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGCATGTCGCACACCTCTCCTG |

| novel_mir46 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGAGGCAGTGTATTGTTAGTTAG |

| miR-1805-3p_1 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTGTATTGGAACACTACAG |

| novel_mir66 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTGTATTGGAACACTACAG |

| miR_218-3p_2 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGATGGTTCTGTCAAGCAC |

| miR-183 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTATGGCACTGGTAGAATTC |

| novel_mir443 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTTGGGAACTTGCTGTC |

| novel_mir2 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTTAGTGCGCAGTAAGCTAG |

| miR-122 | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTGGAGTGTGACAATGGTGT |

| amiRNA-R | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA |

| U6-F | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| U6-R | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

miRNA-R is the universal reverse primer.

Statistics

The results were expressed as means ± SD. All the qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate and the relative levels were measured in terms of the threshold cycle value (Ct) and were normalized using the equation 2−ΔΔCt. Statistical analysis of all data was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 16, SPSS Inc.). The statistical significance (P < 0.05) was evaluated by one-way ANOVA with simultaneous multiple comparisons among different groups.

Results

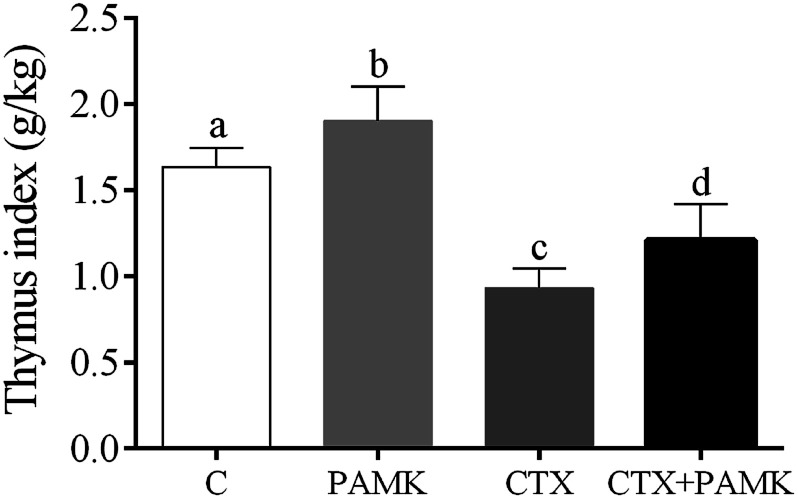

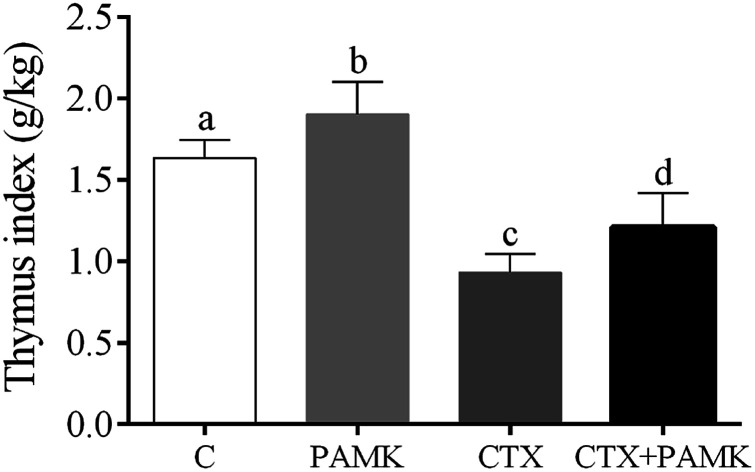

PAMK improves the thymus index in geese

To confirm the effects of PAMK on the thymus of geese, the thymus indexes of four groups were analyzed (Fig. 1). Compared with the control group, the thymus index of the CTX group was significantly decreased (P < 0.05), but the PAMK group was significantly increased (P < 0.05), which indicated that immunosuppression induced by CTX inhibited thymus development but PAMK promoted it. The thymus index of the group treated with PAMK and CTX (CTX + PAMK group) was significantly lower than that of the control group (P < 0.05), but significantly higher than the CTX group (P < 0.05). Thus, PAMK could not only improve the thymus index of the control group, but also improve the decreased thymus index due to CTX treatment; however, PAMK could not restore the index to normal levels.

Fig. 1. Effects of PAMK on the thymus index of CTX-induced geese. Means with the different letters represent statistically significant values (P < 0.05); the bars with a common letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

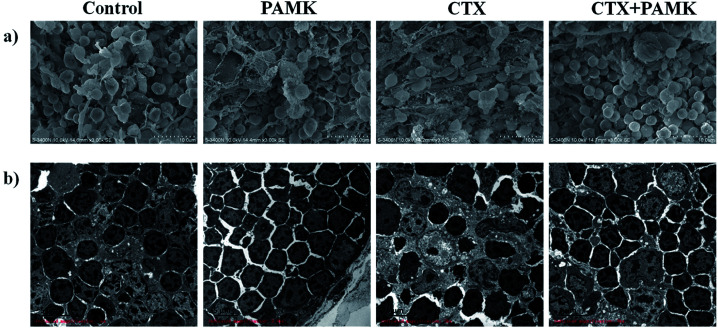

PAMK protects the development and cell morphology of the thymus

In the SEM of the thymus, the densities of thymocytes in the control and PAMK groups were normal, the morphology of cells was regular, and no pathological changes could be observed. In contrast, the CTX group showed low cell density, increased connective tissue, irregular cell morphology, and shrinkage of thymocytes. Compared with the CTX group, the CTX + PAMK group exhibited increased cell density and regular thymocyte morphology (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. (a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM × 3000) of goose thymus at 28 days of age. (b) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM × 3000) of goose thymus at 28 days of age.

TEM of the thymocytes showed that the thymocytes of the CTX group had undergone vacuolization and chromatin margination was observed in the nucleus. In addition, apoptotic bodies were observed. The morphology of the cells of the CTX + PAMK group was improved compared with that of the CTX group. The chromatin was still loose in the nucleus, but chromatin margination was reduced, indicating that thymocytes of geese could be protected from the damaging effects of CTX by feeding with PAMK (Fig. 2b).

The results showed that PAMK could not only increase the thymus index, but could also restore the structure of the thymus to a more normal phenotype, indicating that PAMK could promote the development of the thymus but had no obvious effects on the control group. After treatment with CTX, the immune organ index decreased significantly, the thymus tissue was loose, and cell shrinkage and apoptosis were observed. The results of the CTX + PAMK group showed that PAMK could alleviate the CTX-induced damage to thymus development and cell morphology.

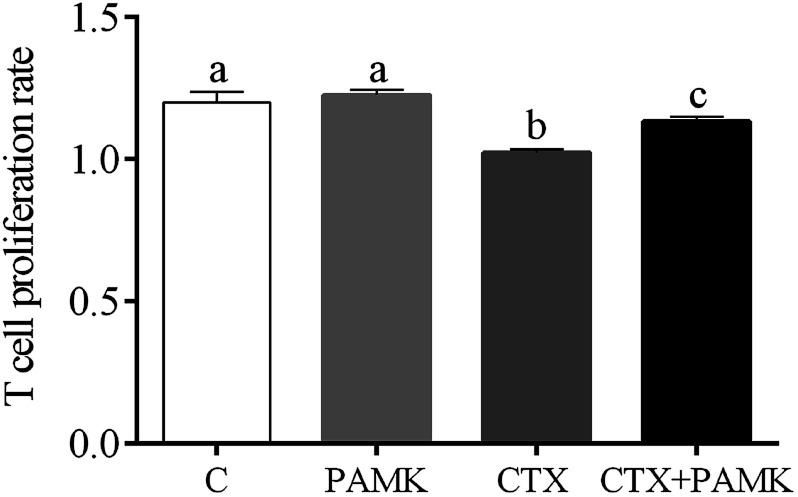

PAMK alleviated CTX-mediated inhibition of T cell proliferation

Compared with the control group, the T cell proliferation rate of the CTX group was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) and the PAMK group showed no significant difference (P > 0.05), indicating that CTX had immunosuppressive effects on T cell proliferation. However, the T cell proliferation rate of the CTX + PAMK group was significantly higher than that of the CTX group (P < 0.05), but remained significantly lower than that of the control and PAMK groups (P < 0.05). The results indicated PAMK had no significant effects on T cell proliferation in normal geese, but increased the CTX-inhibited T cell proliferation, albeit not up to the normal level (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Effects of PAMK on the T cell proliferation rate in CTX -treated geese. Means with the different letters represent statistically significant values (P < 0.05); the bars with a common letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

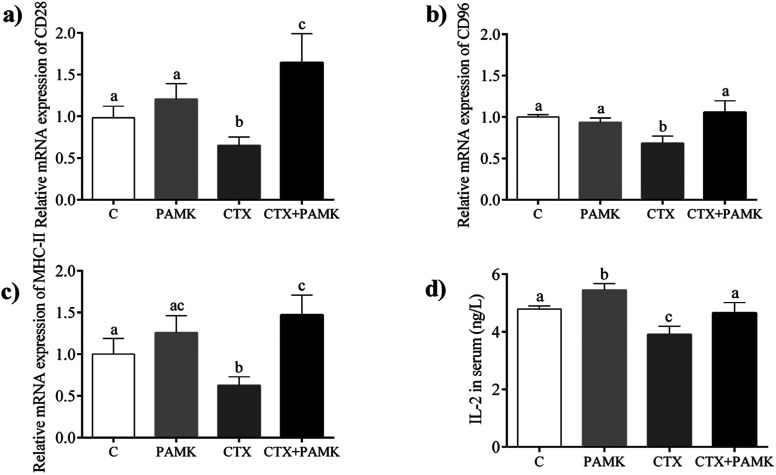

PAMK increased T cell activation-related gene expression

The mRNA expression of CD28, CD96, and MHC-II, which are associated with the activation and maturation of T cells, were tested in the homogenized entire thymus. As shown in Fig. 4, the relative mRNA expressions of CD28, CD96, and MHC-II in the CTX group decreased significantly (P < 0.05) compared with those in the control group, indicating that CTX significantly inhibited T cell activation. The relative mRNA expressions of CD28, CD96, and MHC-II in the PAMK group showed no significant differences compared with those of the control group (P > 0.05), while in the CTX + PAMK group, their expressions were significantly higher than those of the CTX group (P < 0.05). It should be noted that the relative mRNA expression of CD96 in the CTX + PAMK group showed no significant difference compared with that of the control group (P > 0.05), whereas the relative mRNA levels of CD28 and MHC-II in the CTX + PAMK group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.05). Thus, PAMK could not significantly affect the expressions of T cell activation related genes in normal geese but increased the expressions of mRNA downregulated by CTX to normal or higher levels.

Fig. 4. Effects of PAMK on T cell activation-related genes in CTX-treated geese. (a) Relative mRNA expression of CD28. (b) Relative mRNA expression of CD96. (c) Relative mRNA expression of MHC-II. (d) Effects of PAMK on the IL-2 content of CTX-treated geese. Means with the different letters represent statistically significant values (P < 0.05); the bars with a common letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

PAMK increased the IL-2 content in serum

Compared with the control group, the IL-2 level in the serum of the CTX group was significantly decreased (P < 0.05), but the PAMK group increased significantly (P < 0.05), indicating that CTX inhibited but PAMK promoted IL-2 secretion in geese (Fig. 4d). However, the IL-2 level in the serum of the CTX + PAMK group was significantly higher than that in the CTX group (P < 0.05), and had no significant difference compared with that of the control group (P > 0.05). The results indicated that PAMK not only increased the IL-2 levels in normal geese but also increased the IL-2 level in geese treated with CTX.

Bioinformatics analyses of miRNA sequencing

After removing low-quality reads and adaptor sequences, clean reads of each sample were obtained, respectively (Table 3). The percentage of clean reads among the raw tags was greater than 96% for each sample. Clean reads were used to summarize the length distribution. The results showed that most clean reads were in 21–24 nt length. Generally, miRNAs are 21 nt or 22 nt, short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are 24 nt, and piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are between 28 to 30 nt.

Summary of sequencing data for each sample.

| Sample name | Raw tag count | Clean reads count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control-1 | 12 268 083 | 11 987 864 | 97.72 |

| Control-2 | 11 576 318 | 11 351 789 | 98.06 |

| Control-3 | 11 849 430 | 11 607 797 | 97.96 |

| PAMK-1 | 12 359 670 | 12 069 858 | 97.66 |

| PAMK-2 | 11 550 925 | 11 190 488 | 96.88 |

| PAMK-3 | 12 388 333 | 12 103 559 | 97.70 |

| CTX-1 | 11 545 051 | 11 268 052 | 97.60 |

| CTX-2 | 11 832 741 | 11 487 523 | 97.08 |

| CTX-3 | 12 509 679 | 12 080 906 | 96.57 |

| CTX + PAMK-1 | 11 931 196 | 11 585 937 | 97.11 |

| CTX + PAMK-2 | 12 116 956 | 11 749 233 | 96.97 |

| CTX + PAMK-3 | 12 029 029 | 11 656 445 | 96.90 |

The statistics for the alignment of the tags to the reference genome for the control group, PAMK group, CTX group, and CTX + PAMK group were 93.05%, 93.50%, 83.35%, and 80.43%, respectively. A higher ratio of alignment indicates a closer genetic relationship between the sample and reference species. A lower rate may be caused by low similarity with the reference species or by contamination.

Small RNAs (sRNAs) prediction

After sRNA annotation, unknown tags were used to predict novel sRNAs and novel miRNAs, based on their architectural features. Ultimately, 490 novel miRNAs and 662 novel siRNAs were predicted from among 1048576 unknown sRNAs, accounting for 0.048% and 0.063%, respectively.

Differentially expressed miRNAs

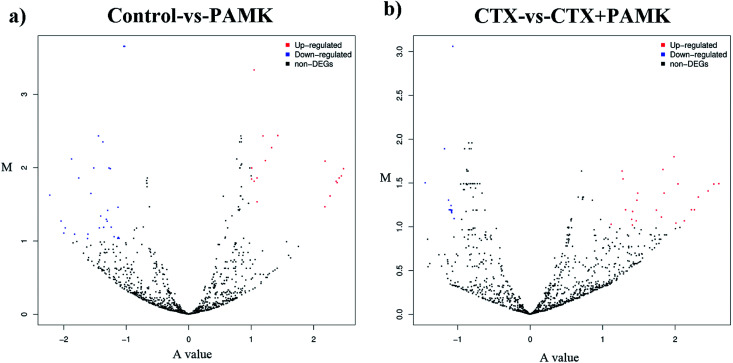

After identifying the differentially expressed miRNAs, volcano plots were used to show the distribution of the differentially expressed miRNAs in the control vs. PAMK and CTX vs. CTX + PAMK comparisons (Fig. 5a and b). After normalization and T-testing of the sequencing data, 37 differentially expressed miRNAs were found between the control group and the PAMK group (20 upregulated and 17 downregulated); of these, 13 were known miRNAs and 24 were novel miRNAs (Table 4). In addition, 42 differentially expressed miRNAs were found between the CTX group and the CTX + PAMK group (32 upregulated and 10 downregulated); of these, 14 were known miRNAs and 28 were novel miRNAs (Table 5). MiR-218-3p_2, novel_mir46, and novel_mir19 were differentially expressed in both comparisons. Among them, novel_mir46 was upregulated in both results, while miR-218-3p_2 and novel_mir19 had opposite effects in the two results.

Fig. 5. (a) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed miRNAs of the control vs. PAMK. (b) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed miRNAs of CTX vs. CTX + PAMK. The A value on the x-axis represents the average level after log2 conversion; the M value on the y-axis represents the difference multiple after log2 conversion. Red means upregulated; blue means downregulated; and black means no significant difference.

Differential expression of miRNAs in the thymus of geese between the control and PAMK groupsa.

| miR-name | Control read | PAMK read | log2 ratio | Up/down-regulation | P-value | Significance level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| novel_mir66 | 0 | 15 | 5.003986249 | Up | 4.91 × 10−5 | ** |

| novel_mir209 | 0 | 14 | 4.904450575 | Up | 9.19 × 10−5 | ** |

| novel_mir358 | 0 | 12 | 4.682058154 | Up | 0.000327404 | ** |

| novel_mir327 | 0 | 12 | 4.682058154 | Up | 0.000327404 | ** |

| novel_mir467 | 0 | 11 | 4.556527272 | Up | 0.000623823 | ** |

| novel_mir456 | 0 | 11 | 4.556527272 | Up | 0.000623823 | ** |

| miR-122_1 | 80 | 1255 | 4.068639207 | Up | 3.78 × 10−276 | ** |

| miR-122-3p_2 | 85 | 1302 | 4.03421845 | Up | 5.65 × 10−285 | ** |

| miR-122-3p_4 | 90 | 1278 | 3.924914678 | Up | 4.57 × 10−275 | ** |

| miR-122 | 87 | 1198 | 3.88056435 | Up | 4.16 × 10−256 | ** |

| miR-122-5p | 96 | 1252 | 3.802152 | Up | 5.89 × 10−264 | ** |

| miR-122_2 | 95 | 1236 | 3.798703073 | Up | 1.89 × 10−260 | ** |

| miR-122-3p_3 | 100 | 1263 | 3.755878387 | Up | 4.93 × 10−264 | ** |

| novel_mir404 | 78 | 303 | 2.054867418 | Up | 8.34 × 10−36 | ** |

| novel_mir28 | 12 | 46 | 2.035695109 | Up | 1.31 × 10−6 | ** |

| novel_mir46 | 48 | 128 | 1.512133153 | Up | 5.26 × 10−11 | ** |

| miR-218a | 1038 | 2530 | 1.382426595 | Up | 6.47 × 10−164 | ** |

| miR-206-3p | 2266 | 4800 | 1.179982198 | Up | 4.76 × 10−242 | ** |

| miR-206 | 2303 | 4826 | 1.164409158 | Up | 2.70 × 10−238 | ** |

| novel_mir16 | 41 | 77 | 1.006330189 | Up | 0.000217115 | ** |

| miR-218-3p_2 | 1094 | 505 | −1.018161792 | Down | 3.53 × 10−42 | ** |

| novel_mir8 | 440 | 202 | −1.026052577 | Down | 3.76 × 10−18 | ** |

| novel_mir12 | 160 | 72 | −1.05490744 | Down | 8.41 × 10−8 | ** |

| novel_mir460 | 84 | 35 | −1.165938752 | Down | 2.56 × 10−5 | ** |

| miR-19b-2-5p | 8028 | 3275 | −1.196450057 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-16b-3p_2 | 47 | 18 | −1.287568197 | Down | 0.000662984 | ** |

| novel_mir393 | 69 | 22 | −1.551997185 | Down | 2.04 × 10−6 | ** |

| novel_mir20 | 110 | 27 | −1.929376558 | Down | 2.89 × 10−12 | ** |

| novel_mir399 | 29 | 7 | −1.95353042 | Down | 0.000300161 | ** |

| novel_mir87 | 25 | 6 | −1.961798036 | Down | 0.000762743 | ** |

| novel_mir177 | 131 | 28 | −2.128972426 | Down | 4.55 × 10−16 | ** |

| novel_mir262 | 29 | 6 | −2.175922841 | Down | 0.000106849 | ** |

| novel_mir448 | 39 | 8 | −2.188306566 | Down | 6.51 × 10−6 | ** |

| novel_mir366 | 19 | 2 | −3.15083186 | Down | 0.000125388 | ** |

| novel_mir426 | 21 | 1 | −4.295221769 | Down | 6.55 × 10−6 | ** |

| novel_mir19 | 66 | 3 | −4.362335965 | Down | 1.03 × 10−15 | ** |

| novel_mir443 | 13 | 0 | −4.603344065 | Down | 0.000313854 | ** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Differential expression of miRNAs in the thymus of geese between the CTX and CTX + PAMK groupsa.

| miR-name | CTX read num | CTX + PAMK read num | log2 ratio | Up–down regulation | P-value | Significance level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| novel_mir457 | 0 | 19 | 5.295854409 | Up | 5.18 × 10−6 | ** |

| novel_mir254 | 1 | 16 | 4.047926896 | Up | 7.24 × 10−5 | ** |

| novel_mir331 | 1 | 16 | 4.047926896 | Up | 7.24 × 10−5 | ** |

| novel_mir168 | 4 | 37 | 3.257380262 | Up | 2.56 × 10−8 | ** |

| miR-103a-5p | 3 | 20 | 2.78489249 | Up | 0.000145192 | ** |

| novel_mir490 | 3 | 18 | 2.632889397 | Up | 0.000468029 | ** |

| novel_mir224 | 31 | 181 | 2.593576473 | Up | 3.71 × 10−28 | ** |

| novel_mir13 | 18 | 96 | 2.462964395 | Up | 7.04 × 10−15 | ** |

| novel_mir19 | 5 | 26 | 2.426438519 | Up | 5.92 × 10−5 | ** |

| novel_mir33 | 4 | 20 | 2.369854991 | Up | 0.000512685 | ** |

| novel_mir64 | 14 | 58 | 2.098552969 | Up | 4.00 × 10−8 | ** |

| miR-2188-5p_1 | 6 | 24 | 2.047926896 | Up | 0.000506439 | ** |

| novel_mir80 | 7 | 27 | 1.995459476 | Up | 0.000287185 | ** |

| novel_mir361 | 15 | 57 | 1.973926314 | Up | 1.68 × 10−7 | ** |

| novel_mir46 | 37 | 125 | 1.804257815 | Up | 3.03 × 10−13 | ** |

| novel_mir392 | 48 | 162 | 1.802814398 | Up | 1.06 × 10−16 | ** |

| novel_mir113 | 9 | 29 | 1.73598289 | Up | 0.000625848 | ** |

| novel_mir263 | 38 | 122 | 1.73073672 | Up | 2.56 × 10−12 | ** |

| novel_mir451 | 12 | 37 | 1.672417761 | Up | 0.000167905 | ** |

| novel_mir133 | 20 | 58 | 1.583979796 | Up | 5.87 × 10−6 | ** |

| miR-218b_3 | 251 | 650 | 1.42067925 | Up | 1.66 × 10−44 | ** |

| novel_mir71 | 18 | 44 | 1.337433513 | Up | 0.000505705 | ** |

| miR-218-5p | 260 | 628 | 1.320179832 | Up | 1.10 × 10−38 | ** |

| novel_mir278 | 53 | 126 | 1.297286365 | Up | 9.02 × 10−9 | ** |

| miR-218-3p_3 | 284 | 646 | 1.233570131 | Up | 6.26 × 10−36 | ** |

| miR-218-2-3p | 293 | 658 | 1.215113815 | Up | 9.53 × 10−36 | ** |

| miR-218-3p_2 | 294 | 647 | 1.185876453 | Up | 6.53 × 10−34 | ** |

| novel_mir4 | 177 | 383 | 1.161521928 | Up | 4.05 × 10−20 | ** |

| miR-218-3p_1 | 305 | 638 | 1.112674077 | Up | 2.22 × 10−30 | ** |

| novel_mir273 | 90 | 185 | 1.08745526 | Up | 1.41 × 10−9 | ** |

| novel_mir2 | 1643 | 3238 | 1.026697401 | Up | 4.57 × 10−129 | ** |

| novel_mir9 | 102 | 200 | 1.019357744 | Up | 2.35 × 10−9 | ** |

| novel_mir363 | 65 | 30 | −1.067550322 | Down | 0.000506556 | ** |

| miR-183_1 | 8203 | 3532 | −1.16773939 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-183 | 8066 | 3472 | −1.168159562 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-183_2 | 8184 | 3423 | −1.209617957 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-183-5p | 8391 | 3507 | −1.210678428 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-183-3p_1 | 8220 | 3379 | −1.234615148 | Down | 0 | ** |

| miR-183_3 | 8364 | 3436 | −1.23553613 | Down | 0 | ** |

| novel_mir126 | 209 | 79 | −1.355651488 | Down | 4.98 × 10−14 | ** |

| novel_mir37 | 47 | 16 | −1.506661956 | Down | 0.000110035 | ** |

| miR-1805-3p_1 | 23 | 5 | −2.153706965 | Down | 0.000546189 | ** |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

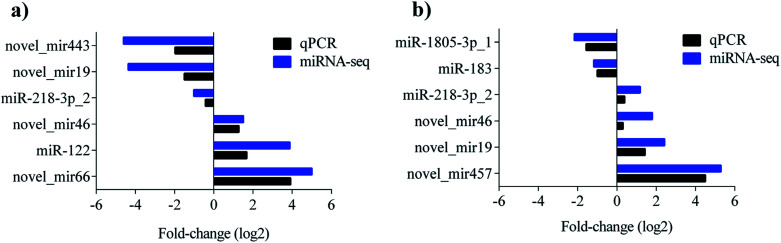

Validation of the expression of partial difference miRNAs

To validate the sequencing result, 9 miRNAs showing significant differences in the comparisons were selected for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) detection. The levels of novel_mir443, novel_mir19, miR-218-3p_2 were upregulated, while novel_mir46, miR-122, and novel_mir66 were downregulated in the control vs. PAMK. The levels of miR-1805-3p_1 and miR-183 were upregulated, while miR-218-3p_2, novel_mir46, novel_mir19, and novel_mir457 were downregulated in CTX vs. CTX + PAMK. All the qPCR results were in agreement with the miRNA sequencing results (Fig. 6a and b).

Fig. 6. (a) Comparison results of miRNA sequencing and qPCR of control vs. PAMK. (b) Comparison results of miRNA sequencing and qPCR of CTX vs. CTX + PAMK. Blue represents the results of miRNA sequencing; black represents the results of miRNA qPCR.

Novel_mir2 is involved in the immunomodulation of PAMK

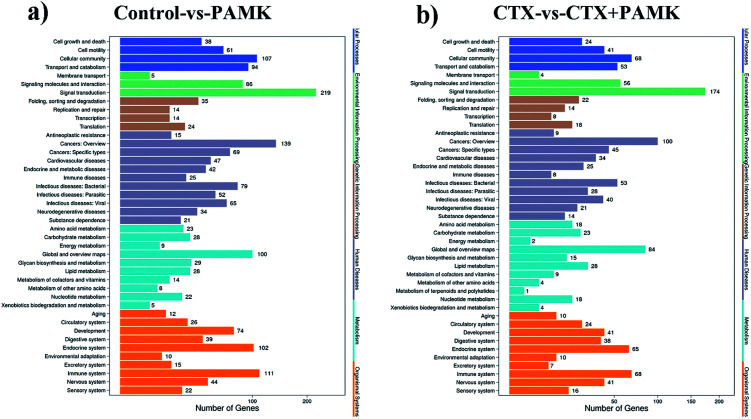

To obtain more accurate data, the RNAhybrid and miRanda software were used to predict the target genes of the differentially expressed miRNAs. Combined with the filter conditions, such as free energy and score values for filtering, the filtered results showed that RNAhybrid predicted 41 169 and miRanda predicted 16 726 target genes, among which 16 334 target genes were predicted by both algorithms. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of these target genes revealed that they were related to signal transduction, cancers (overview), immune system, and global and overview maps signal pathways (Fig. 7a and b). The fold change in miRNA expression was used to represent the difference in the expression of the target genes, and then we summed the total miRNA fold change related to the KEGG pathways. The major enriched KEGG pathways in the immune system in the CTX vs. CTX + PAMK comparison were the chemokine signaling pathway, complement and coagulation cascades, platelet activation, toll-like receptor signaling pathway, NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, hematopoietic cell lineage, T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway, and natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity (Table 6). T cell activation can be regulated by the TCR signaling pathway; therefore, the TCR signaling pathway was selected for further analysis of the differentially expressed miRNAs and their target mRNAs.

Fig. 7. (a) Enrichment of KEGG pathways based on target genes of control vs. PAMK. (b) Enrichment of KEGG pathways based on target genes of CTX vs. CTX + PAMK. The x-axis is the target gene number of the miRNA; the right y-axis shows the pathway terms, divided into six categories with different colors.

The majority KEGG enriched in the immune system in CTX vs. CTX + PAMK.

| Pathway | DEGs genes with pathway annotation (23 476) | All genes with pathway annotation (28 984) | P value | Q value | Pathway ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet activation | 750 (3.19%) | 882 (3.04%) | 0.000846 | 2.94 × 10−2 | ko04611 |

| Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 287 (1.22%) | 337 (1.16%) | 0.026657 | 2.78 × 10−1 | ko04666 |

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | 358 (1.52%) | 424 (1.46%) | 0.037209 | 3.10 × 10−1 | ko04640 |

| B cell receptor signaling pathway | 212 (0.9%) | 252 (0.87%) | 0.115164 | 5.63 × 10−1 | ko04662 |

| Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 200 (0.85%) | 238 (0.82%) | 0.131098 | 5.78 × 10−1 | ko04664 |

| NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 179 (0.76%) | 213 (0.73%) | 0.146814 | 6.13 × 10−1 | ko04621 |

| Antigen processing and presentation | 81 (0.35%) | 95 (0.33%) | 0.176778 | 6.83 × 10−1 | ko04612 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 234 (1%) | 282 (0.97%) | 0.220589 | 7.94 × 10−1 | ko04620 |

| Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 744 (3.17%) | 919 (3.17%) | 0.532457 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04670 |

| Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 270 (1.15%) | 336 (1.16%) | 0.648932 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04650 |

| Intestinal immune network for IgA production | 80 (0.34%) | 103 (0.36%) | 0.838767 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04672 |

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | 330 (1.41%) | 418 (1.44%) | 0.871833 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04660 |

| RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | 120 (0.51%) | 156 (0.54%) | 0.917 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04622 |

| Chemokine signaling pathway | 408 (1.74%) | 523 (1.8%) | 0.963163 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04062 |

| Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 66 (0.28%) | 95 (0.33%) | 0.997703 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04623 |

| Complement and coagulation cascades | 168 (0.72%) | 247 (0.85%) | 1 | 1.00 × 1000 | ko04610 |

We chose mRNAs that were most highly regulated by miRNAs in the CTX vs. CTX + PAMK and that encoded members of the TCR signaling pathway and then identified the corresponding miRNA. Target genes with the highest fold change in the TCR signaling pathway are shown in Table 7. The results for novel_mir2 in the control vs. PAMK and CTX vs. CTX + PAMK comparisons showed that the differential expression of novel_mir2 was not significant in control vs. PAMK, but its expression increased significantly in CTX vs. CTX + PAMK (Table 8). The expression of novel_mir2 has the same tendency as the results of thymus development and T cell activation above. Thus, the PAMK-mediated alleviation of immune damage in geese is closely related to the expression of novel_mir2.

Partial miRNAs and target genes in the TCR pathway.

| Target gene | miRNA |

|---|---|

| CD 28 | novel_mir2; novel_mir4; miR-122 |

| CTLA4 | novel_mir2 |

| PI3K | novel_mir224; novel_mir2; novel_mir3; novel_mir4 |

Comparison of novel_mir2 in the control vs. PAMK and CTX vs. CTX + PAMK.

| Comparison group (A vs. B) | Read num A | Read num B | log2 ratio (A/B) | Up–down regulation | P-value | Significance level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs. PAMK | 1562 | 1427 | −0.382 | Down | 0.485 | Not significance |

| CTX vs. CTX + PAMK | 1643 | 3238 | 1.027 | Up | 4.57 × 10−129 | ** |

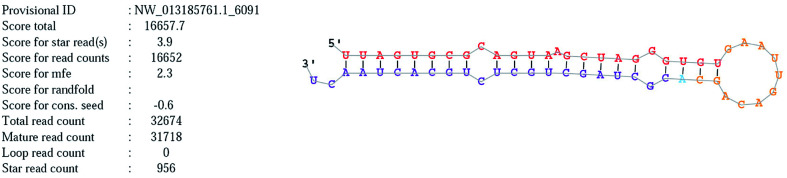

Novel_mir2 targets CTLA4 to regulate the TCR pathway

Novel_mir2 is a newly annotated miRNA that is located on chromosome NW_013185761. The mature and precursor sequences of novel_mir2 are shown in Table 7. The stem loop structure of novel_mir2 was predicted and is shown in Fig. 8. It showed that novel_mir2 is a miRNA, not a fragment of an mRNA (Table 9).

Fig. 8. The stem loop structure of novel_mir2.

Characteristics of novel_mir2.

| miRNA ID | Novel_mir2 |

|---|---|

| Chromosome | NW_013185761 |

| Sequence(mature) | uuagugcgcaguaagcuagggugu |

| Sequence(star) | cgcuagcugcucugcacuaacu |

| Sequence(precursor) | uuagugcgcaguaagcuagggugugaauugacagcacgcuagcugcucugcacuaacu |

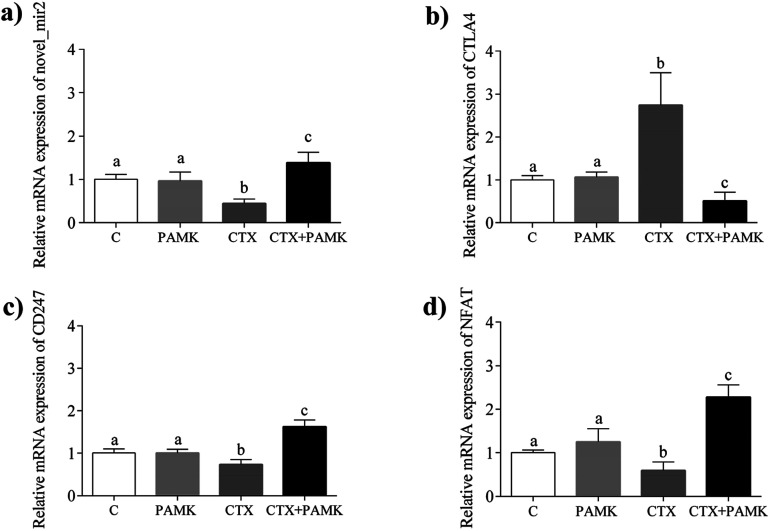

To confirm the differences in novel_mir2 expression between the groups, qPCR was used to detect novel_mir2 expression. The results showed that the relative mRNA expression of novel_mir2 between the control and PAMK groups was not significantly different (P > 0.05). However, its relative expression in the CTX + PAMK group was significantly higher than that in the CTX group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 9a), which is consistent with the sequencing results.

Fig. 9. Relative mRNA expression of novel_mir2 and partial TCR pathway genes. (a) Relative mRNA expression of novel_mir2. (b) Relative mRNA expression of CTLA4. (c) Relative mRNA expression of CD247. (d) Relative mRNA expression of NFAT. Means with the different letters represent statistically significant values (P < 0.05); the bars with a common letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Based on the target gene prediction results of miRNA sequencing, novel_mir2 could target multiple mRNAs in the TCR signaling pathway, such as CD28, CTLA4, and PI3K. CTLA4 can only be targeted by novel_mir2, while CD28 and PI3K can also be targeted by other miRNAs. In addition, CD28 and CTLA4 are very important genes in the TCR pathway. Their encoded proteins competitively bind to the same ligands, CD86 and CD80, during T cell activation. When CD28 binds to the ligands, CD28 is activated and T cell activation is promoted. When CTLA4 binds to the ligands, the TCR-CD3 pathway is inhibited so that T cell activation is inhibited. The qPCR results for CTLA4 showed that its expression had the opposite tendency to that of novel_mir2 (Fig. 9b), while the expression of CD28 showed the same expression pattern as novel_mir2 (Fig. 4a). Thus, novel_mir2 targets the expression of CTLA4. To further confirm whether novel_mir2 regulates T cell activation by targeting CTLA4, the mRNA levels of CD247 (CD3 zeta) and the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) in the TCR signaling pathway were detected. The results showed that the mRNA expression patterns of CD247 and NFAT were the opposite to that of CTLA4 (Fig. 9c and d). CTLA4 expression showed no significant difference between the control group and the PAMK group (P > 0.05); however, in the CTX + PAMK group, its expression was significantly higher than that in the CTX group (P < 0.05). The trend of CTLA4 expression was the opposite to that of novel_mir2, which suggested that novel_mir2 regulates CTLA4. In addition, the expression patterns of CTLA4, CD247, and NFAT were in line with the mechanism of the TCR signaling pathway, indicating that CTLA4 is involved in the regulation of the TCR signaling pathway.

Discussion

Cyclophosphamide (CTX) is often used to construct immunosuppressed models to study immune function in mammals and poultry because of the inhibition of humoral and cellular immunity.2,24 Therefore, in this research an immunosuppressed model of geese was prepared with the injection of CTX. The results showed that CTX reduced the thymus index, inhibited thymus development, led to thymocyte shrinkage and apoptosis, inhibited T cell proliferation and T cell activation, revealing that immunosuppression was successfully constructed in geese.

As reported, the immune enhancing effects of PAMK were mainly in promoting immune organ development, lymphocyte proliferation, antioxidant ability and secretion of cytokines in mice and chickens.5,10,25 Here, we found that PAMK also promoted thymus development, T lymphocyte proliferation in geese, suggesting that there was no species difference in waterfowl, poultry and mammals. However, PAMK had no significant pathological effects on the thymus structure of normal geese, as well as the spleen structure of chickens.5 Besides, PAMK was first claimed to alleviate the immunosuppressive effects induced by CTX in this study. Lots of polysaccharides of traditional Chinese herbs have been reported as having the effects of alleviating immune suppression, similar to PAMK. Chuanminshen violaceum polysaccharide (CVP) was proven to overcome the CTX-induced immunosuppression of mice by raising IL-2 levels in serum, while Cordyceps militaris polysaccharides (CMP) were mainly via the function of macrophages and anti-oxidative activity in immunosuppressed mice.2,3 However, we found that PAMK alleviated CTX-induced immunosuppression closely related to T cell activation according to the changes in CD28, CD96, MHC II, and IL-2. T cell activation requires a dual-signal in the TCR pathway: the TCR-CD3 complex binds to the antigen peptide-MHC molecule, and the CD molecule on the T cell surface binds to the corresponding ligand on the surface of the antigen presenting cell (APC), which is a CD28 activation signal and a CD152 inhibitory signal.26 Besides, CD96 expression was positively associated with CD4+ T cell counts and was upregulated during T cell activation (23).27 In addition, Curtsinger28 suggested a third signal for T cell activation, which stimulated CD8+ T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion (IL-2, IL-12). IL-2 is also an important cytokine secreted by activated T cells.29 For these reasons, CD28, CD152, CD96, MHC II, and IL-2 are the typical molecular signs of T cell activation, and PAMK alleviated CTX-induced immunosuppression might through the TCR pathway.

It has been reported that miRNAs could regulate the target genes in the TCR pathway, thereby regulating T cell activation.17,19 Although each miRNA targets different genes and regulates different pathways, most of them eventually alter the expression of NF-κB, thereby regulating the activation of T cells. The present study has shown that PAMK alleviated the inhibition of T cell activation induced by CTX mainly through the upregulation of novel_mir2 to degrade or inhibit the translation of CTLA4. Coincidentally, it was reported that miR-155 promotes T cell activation by targeting CTLA4, which is the negative regulator of T cell activation in humans.20 CTLA4 is also called CD152, which inhibits T cell activation by inhibiting the expression of the TCR-CD3 complex or ZAP70 and finally inhibits the TCR pathway. Thus, the inhibition of T cell activation induced by CTX was due to the high expression of CTLA4 and inhibited the downstream activation of the TCR pathway, and the alleviation of PAMK on immunosuppression was due to the low expression of CTLA4 and the activation of the TCR pathway. According to the results, the changes in CD28 and CTLA4 in the CTX and CTX + PAMK groups are all opposite. The novel_mir2 did not directly target CD28 to regulate T cell activation but targeted CTLA4 so that the ability of CTLA4 to compete with CD28 to bind CD80 and CD86 was inhibited. Thus, the increased expression of CD28 might further promote the TCR pathway because it binds more ligands. However, some reports found that the changes in CD28 and CTLA4 are the same in the regulation of T cell activation in vitro.30 The simultaneous increase in CD28 and CTLA4 is inconsistent with the regulatory mechanism of T cell activation. The reason may be that there are no APCs with ligands cultured in vitro for CD28 to compete with CTLA4. In addition, NFAT is an important nuclear transcription factor of T cell activation that is also regulated by miRNAs.31,32 In the present study, we found that PAMK treatment significantly increased the expression of NFAT in the presence of CTX, but not NF-κB, indicating that PAMK might upregulate the expression of novel_mir2 to inhibit CTLA4, leading to increased levels of nuclear transcription factor NFAT, which ultimately changes the expression of cytokines and promotes T cell activation. This means that the mechanism by which PAMK promotes T cell activation, inhibited by CTX in geese, is not the same as the mechanism by which CMP promotes macrophage activation.2

Conclusions

In conclusion, PAMK upregulates novel_mir2 expression, which targets and inhibits CTLA4 expression, leading to the promotion of T cell activation through the TCR-NFAT pathway, ultimately alleviating the immune suppression induced by CTX in geese. This study is the first to systematically analyze the effects of PAMK on immunosuppressed geese.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

Activator protein-1

- APC

Antigen presenting cell

- CMP

Cordyceps militaris polysaccharides

- CTLA4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4

- CTX

Cyclophosphamide

- CVP

Chuanminshen violaceum polysaccharide

- GO

Gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- ncRNA

Non-coding RNA

- NFAT

Nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- PAMK

Polysaccharide of atractylodes macrocephala koidz

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PHA

Phytoagglutinin

- rRNAs

Ribosomal RNAs

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- snoRNAs

Small nucleolar RNAs

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TPM

Transcripts per kilobase million

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to Inter-governmental S & T Exchange Project between China and Belarus (No. CB01-13); Science & Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No. 201604020061); Modern Agriculture Industry Technology System of Guangdong (No. 2016LM1113).

References

- Ma C. Yue Q. X. Guan S. H. Wu W. Y. Yang M. Jiang B. H. Liu X. Guo D. A. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:1841–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. Meng X. Y. Yang R. L. Qin T. Wang X. Y. Zhang K. Y. Fei C. Z. Li Y. Hu Y. Xue F. Q. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;89:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Zhang Y. Song X. Yin Z. Jia R. Zhao X. Lai X. Wang G. Liang X. He C. Yin L. Lv C. Zhao L. Shu G. Ye G. Shi F. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8:558–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. Long F. Zhang X. Yang Y. Jiang X. Wang L. Oncotarget. 2017;8:77500–77514. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D. Li B. Cao N. Li W. Tian Y. Huang Y. Oncotarget. 2017;8:70394–70405. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. Sun Y. L. Wang A. H. Xu C. E. Zhang M. Y. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:9285–9290. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W. Zhang S. Hao P. Zheng P. Liu J. Zhao X. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;153:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G. Q. Chen R. Q. Zheng J. X. Pharm. Biol. 2015;53:512–517. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.929152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. Meng K. Qi C. Yang X. Wang Y. Fan W. Yan Z. Zhao X. Liu J. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;126:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Chen X. Yue C. Hou R. Chen J. Lu Y. Li X. Li R. Liu C. Gao Z. Li E. Li Y. Wang H. Yan Y. Li H. Hu Y. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;72:1435–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G.-Q. Chen R.-Q. Zheng J.-X. Pharm. Biol. 2014;53:512–517. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.929152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D. Li W. Huang Y. He J. Tian Y. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014;160:232–237. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0056-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D. Tian Y. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015;168:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allantaz F. Cheng D. T. Bergauer T. Ravindran P. Rossier M. F. Ebeling M. Badi L. Reis B. Bitter H. D'Asaro M. Chiappe A. Sridhar S. Pacheco G. D. Burczynski M. E. Hochstrasser D. Vonderscher J. Matthes T. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroesen B. J. Teteloshvili N. Smigielska-Czepiel K. Brouwer E. Boots A. M. van den Berg A. Kluiver J. Immunology. 2015;144:1–10. doi: 10.1111/imm.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I. S. Park C. Y. Mavropoulos A. Shariat N. Pollack J. L. Barczak A. J. Erle D. J. McManus M. T. Anderson M. S. Jeker L. T. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.-J. Chau J. Ebert P. J. R. Sylvester G. Min H. Liu G. Braich R. Manoharan M. Soutschek J. Skare P. Klein L. O. Davis M. M. Chen C.-Z. Cell. 2007;129:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henao-Mejia J. Williams A. Goff L. A. Staron M. Licona-Limon P. Kaech S. M. Nakayama M. Rinn J. L. Flavell R. A. Immunity. 2013;38:984–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler D. Brocke-Heidrich K. Pfeifer G. Stocsits C. Hackermuller J. Kretzschmar A. K. Burger R. Gramatzki M. Blumert C. Bauer K. Cvijic H. Ullmann A. K. Stadler P. F. Horn F. Blood. 2007;110:1330–1333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly E. Janson P. Majuri M. L. Savinko T. Fyhrquist N. Eidsmo L. Xu N. Meisgen F. Wei T. Bradley M. Stenvang J. Kauppinen S. Alenius H. Lauerma A. Homey B. Winqvist O. Stahle M. Pivarcsi A. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;126(581–589):e581–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K. Wang Q. Jia J. Zhao H. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1010428317707882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker T. B. Lee S.-H. Tang W. W. Wallace J. A. Alexander M. Runtsch M. C. Larsen D. K. Thompson J. Ramstead A. G. Voth W. P. Hu R. Round J. L. Williams M. A. O'Connell R. M. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:18530–18541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.808121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H. D. Wu Q. Zhang Z. W. Li S. Wang X. L. Lei X. G. Xu S. W. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. Liu J. Hu Y. Wang D. Li Z. Zhang J. Qin T. Liu X. Liu C. Zhao X. Fan Y. P. Han G. Nguyen T. L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;90:1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. Meng K. Qi C. Yang X. Wang Y. Fan W. Yan Z. Zhao X. Liu J. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;126:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher P. Cohn M. Science. 1970;169:1042–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3950.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson E. M. Keh C. E. Deeks S. G. Martin J. N. Hecht F. M. Nixon D. F. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger J. M. Schmidt C. S. Mondino A. Lins D. C. Kedl R. M. Jenkins M. K. Mescher M. F. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagoulias I. Georgakopoulos T. Aggeletopoulou I. Agelopoulos M. Thanos D. Mouzaki A. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:26707–26721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.762179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuge Z. Y. Zhu Y. H. Liu P. Q. Yan X. D. Yue Y. Weng X. G. Zhang R. Wang J. F. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. Peng X. Zhang X. Wang Y. Zhang L. Gao L. Weng T. Zhang H. Ramchandran R. Raj J. U. Gou D. Liu L. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:25414–25427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.460287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel C. H. Gross F. Karl M. Stephanowitz H. Hennig A. F. Weber M. Gryzik S. Bachmann I. Hecklau K. Wienands J. Schuchhardt J. Herzel H. Radbruch A. Krause E. Baumgrass R. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:24172–24187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.739326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]