Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen, typically associated with contaminated dairy products and deli meats. L. monocytogenes can lead to severe infections in high-risk patient populations; in neonates, listeriosis is rare but carries a high rate of neurological morbidity and mortality. Here a case of neonatal listeriosis, in the newborn of a young Hispanic mother who frequently ate queso fresco (a fresh Mexican cheese), is presented. Pregnant women are commonly counselled to avoid unpasteurised dairy during the pregnancy, but many are unaware that soft cheeses, and other food products, may pose risks for perinatal infection. L. monocytogenes remains a cause of food-related outbreaks and maternal and neonatal sepsis around the world, and healthcare providers should ensure that expectant mothers are carefully counselled regarding potential sources.

Keywords: Infectious diseases, Paediatrics, Obstetrics and gynaecology, Public health, Global Health

Background

Listeria monocytogenes, a major global foodborne pathogen, is most often associated with unpasteurised dairy products. However, consumers may be unaware products made from pasteurised milk, such as soft cheeses, as well as other common foods, such as deli meat, fruits and vegetables, can also be contaminated with L. monocytogenes. Listeriosis remains a significant public health threat. In a meta-analysis of worldwide listeriosis cases from 1996 to 2018, the report of listeriosis outbreaks increased significantly, from 2 major outbreaks in 1996 to 13 in 2018.1 While infection can be asymptomatic in some individuals, the mortality rate can be 20%–30% in high-risk groups such as pregnant women, neonates, individuals older than 65 years of age or in individuals who are immunocompromised. Enhanced attention to sociocultural history, including maternal dietary habits, may help identify and prevent perinatal L. monocytogenes infection.

Case presentation

A young woman in her 20s from a rural community presented to the emergency department at 29 weeks and 5 days gestation with a 3 day history of worsening abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever and signs of preterm labor. The woman reported no previous illnesses during pregnancy and no known sick contacts. This was the woman’s first pregnancy. The extent of prenatal care she had received was unclear, but the few available records indicated she was previously healthy, fully immunised prior to pregnancy and had negative routine infectious disease screening tests at the first prenatal visit that included: hepatitis, herpes simplex, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, measles, mumps and rubella. Shortly after arrival, the expectant mother was started on empiric antibiotics and managed clinically for sepsis. A few hours later, she was taken to the operating room for an emergent c-section due to non-reassuring fetal heart tracings and suspected chorioamnionitis. At delivery, the amniotic fluid was noted to have a green tinge with brown coloured membranes on the fetal side of the placenta. The male preterm baby was floppy and lethargic with poor respiratory effort. His abdomen was distended and had sluggish bowel sounds. He had significant hepatomegaly and appeared diffusely jaundiced. The patient required intubation at 4 min of life and was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). On admission, ampicillin and gentamicin were started, as per NICU protocol in the setting of maternal chorioamnionitis. Over the next 24 hours, the patient had poor peripheral perfusion with capillary refill time of over 3 s, low temperatures down to 35°C and developed generalised anasarca.

Investigations

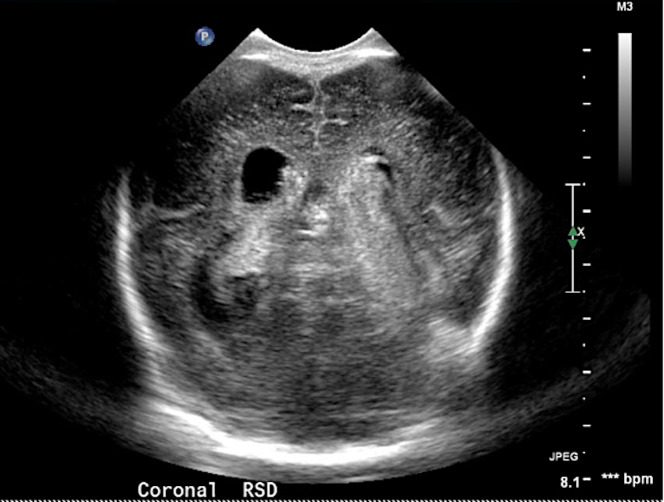

The infant’s initial blood culture grew L. monocytogenes at 29 hours. Additional laboratory studies showed anaemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy and transaminitis. A lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies was initially deferred due to the patient’s clinical instability. Head ultrasound (figure 1) on first day of life, showed grade 4 bilateral intraventricular haemorrhages at the left inferior temporal lobe. The patient was diagnosed with neonatal listeriosis with presumed L. monocytogenes meningitis based on his markedly abnormal neurological examination and intraparenchymal haemorrhage, which is often seen in L. monocytogenes meningitis.2

Figure 1.

Patient cranial ultrasound at day 1 of life demonstrating bilateral grade four intraventricular haemorrhage.

Treatment

Once diagnosed, listeriosis is typically treated with ampicillin (75 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours); often a second agent, such as gentamicin (5 mg/kg/dose every 48 hours), is included initially and maintained when disease is severe. Total duration is usually 14 days for bacteraemia, and 21 days when systemic infection includes central nervous system involvement.3 In this particular case, empiric antibiotic therapy with ampicillin and gentamicin was started at birth, as is common in most early-onset neonatal sepsis protocols. After the diagnosis of listeriosis was made, ampicillin was continued at meningitic (75 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours) dosing for 21 days. Gentamicin was discontinued on day 7, as the patient was clinically improving and no other organisms were identified in culture.

Outcome and follow-up

During his 3 weeks of antibiotic therapy, the patient demonstrated clinical improvement. Multiple CSF cultures were obtained after the patient was clinically stable, all of which were negative. The patient did ultimately develop hydrocephalus, which was felt to be primarily related to his high-grade intraventricular haemorrhage, and had a permanent ventriculoperitoneal shunt placed. The patient is now 3 years old with some neurodevelopmental delays, including delayed speech and motor skills, but is otherwise healthy per parents and available medical records.

Discussion

L. monocytogenes is a gram positive bacillus, but can have both variable gram-staining and morphology, which can lead to initial misidentification. L. monocytogenes can appear as a gram-negative diplococci and be misidentified as Haemophilus or Neisseria, or alternatively as a diptheroid, and dismissed as a contaminant. L. monocytogenes is a facultative anaerobe, traditionally diagnosed by growth in culture or PCR-based methods, especially in cases of antibiotic therapy before the sampling. If PCR testing is not available, maintaining a high suspicion for listeriosis despite a seemingly alternative organism on gram stain is important, especially in at-risk patients who are not clinically improving.

As opposed to most other foodborne pathogens, L. monocytogenes can grow at lower temperatures, from a range of 0°C to 45°C.4 Home refrigerators have an average temperature of 1°C–8°C, which allows L. monocytogenes to survive and grow in contaminated products even with proper refrigeration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises expectant mothers to avoid unpasteurised cheese but to be aware that even pasteurised cheeses, such as queso fresco, can become contaminated during the cheese making process and have been associated with L. monocytogenes infections.5 In theUSA, over the past 9 years, the CDC reports that there have been 20 major L. monocytogenes outbreaks.6 The most significant was a large multistate outbreak in 2011, leading to 33 deaths out of 147 infected individuals (20% mortality).6 Although many of these outbreaks were related to soft cheeses, deli meats are also a common source of outbreaks, and are the likely culprit in recent US outbreaks (cases noted through the end of October 2020) in New York, Massachusetts and Florida.5 6 Even more recently, in February 2021, an outbreak in four states was directly linked to contaminated Hispanic style soft cheeses.5 Melons, apples, hot dogs, smoked salmon and ice cream have also been linked to outbreaks in recent years.5

Early-onset listeriosis (diagnosed within the first 7 days of life, with a mean of 36 hours of life) typically reflects transplacental acquisition via maternal bacteraemia; where as in late onset listeriosis (diagnosed on days 8–30 of life) transmission occurs through the vaginal canal around the time of birth, or less commonly, postnatally from environmental factors.3 7 Pregnant women, most often in their third trimester, can be entirely asymptomatic or present with a simple gastroenteritis, or in the most severe cases, with clinical features of sepsis. In the presumed linked maternal-neonatal case presented here, systemic listeriosis was suspected in the mother given her septic clinical presentation just prior to delivery; receipt of broad-spectrum antibiotics before having specimens obtained may explain why her blood cultures were negative. It is not uncommon for maternal and infant blood cultures to be negative in otherwise microbiologically confirmed cases of neonatal listeriosis. In one French cohort of 88 neonatal listeriosis cases, only 55% of maternal and 41% of infant blood cultures were positive; placental testing in fact had the highest yield at 78% of all cases being positive.8

In a 2010 analysis of 758 listeriosis cases in the USA, 16.9% were pregnancy associated.9 The most common neonatal manifestations reported were meningitis (32.9%) and sepsis (36.5%).9 Neonatal listeriosis occurs in approximately 8.6/100 00 live births in the USA with a 24-time higher risk in Hispanic women and their infants.2 6 A large (separate) meta-analysis estimated 23 150 cases of listeriosis worldwide in 2010, with 20.7% being diagnosed prenatally.6

After the the diagnosis of neonatal listeriosis was made in this case, the patient’s mother was again interviewed to try to identify the source of the L. monocytogenes. In a detailed social history, the mother revealed that she often ate queso fresco (pasteurised fresh Mexican style cheese) bought from a local vendor who came door to door in their migrant, farming community. Queso fresco is a staple of traditional Mexican diet and she had no knowledge that it should be avoided during the pregnancy.

Social and dietary details, components of a patient history that are notoriously overlooked, helped elucidate this challenging case. Although many advances have been made in prevention and detection of the bacterial pathogen, listeriosis remains a significant public health threat in both economically advanced and lower-income countries. It is imperative for healthcare providers to counsel expectant mothers on the risks of listeriosis from deli meats and soft cheeses—especially young Hispanic women and queso fresco.9

Patient’s perspective.

The patient’s family was interviewed and gave consent to share their child’s clinical case for educational purposes. The patient’s mother expressed feeling confused and overwhelmed by the severity of the patient’s clinical course. She stated that eating queso fresco is a common part of her community and she had never been told that it carried a potential risk for infection during pregnancy.**

** These sentiments were directly given by the Mother in her native Spanish, during an interview conducted in Spanish by author GG, who is bilingual.

Learning points.

Listeria monocytogenes remains a major foodborne pathogen throughout the world, with a mortality rate of 20%–30% in pregnant women, neonates and other high-risk groups.

L. monocytogenes infections are most associated with unpasteurised dairy products and soft cheeses, but outbreaks have also been associated with ready-to-eat deli meats, hotdogs, fruits and other common food items.

Counselling groups who may be unaware that foods they consume regularly carry potential risk—such as Hispanic women and queso fresco—is critical to prevent perinatal listeriosis cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: SI provided the initial idea for the case report based on a real life patient case he managed. SI reviewed literature and edited the case report at every step, up until submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

References

- 1.Desai AN, Anyoha A, Madoff LC, et al. Changing epidemiology of Listeria monocytogenes outbreaks, sporadic cases, and recalls globally: a review of ProMED reports from 1996 to 2018. Int J Infect Dis 2019;84:48–53. 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlier C, Perrodeau Élodie, Leclercq A, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:510–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30521-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimberlin DW, Brady MT. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases - Listeria monocytogenes Infections. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018: 511–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker SJ, Archer P, Banks JG. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes at refrigeration temperatures. J Appl Bacteriol 1990;68:157–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Listeria Outbreaks, 2021. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/index.html [Accessed 19 Feb 2021].

- 6.de Noordhout CM, Devleesschauwer B, Angulo FJ, et al. The global burden of listeriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:1073–82. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70870-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamont RF, Sobel J, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. Listeriosis in human pregnancy: a systematic review. J Perinat Med 2011;39:227–36. 10.1515/jpm.2011.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson KA, Gould LH, Hunter JC, et al. Listeriosis Outbreaks Associated with Soft Cheeses, United States, 1998-20141. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:1116–8. 10.3201/eid2406.171051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Listeria public recommendations – Spanish, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/spanish/listeria/pdf/listeria-hispanic-pregnant-women-soft-cheese-fotonovela-spanish-508.pdf [Accessed 25 Jan 2021].