Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate the antiretroviral efficacy and safety of ritonavir (600 mg twice a day [b.i.d.])-saquinavir (400 mg b.i.d.) compared to ritonavir (600 mg b.i.d.) in patients pretreated and receiving continued treatment with two nucleoside analogs. The study was placebo controlled, randomized, and double blind. Inclusion criteria included protease inhibitor naive status and a viral load of >10,000 copies/ml. The main end point was viral load at week 24. Forty-seven patients were included (25 given ritonavir and 22 given ritonavir-saquinavir) and monitored until week 48. At inclusion, 23% had had at least one AIDS-defining event. Previous treatment durations (mean and standard deviation) were 42 ± 25 and 37 ± 23 months, viral loads were 4.75 ± 0.62 and 4.76 ± 0.50 log10 copies/ml, and CD4 cell counts were 236 ± 126 and 234 ± 125/mm3 in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively. At week 24, viral loads were 2.81 ± 1.48 and 2.08 ± 1.14 log10 copies/ml (P = 0.04) and CD4 cell counts were 330 ± 151 and 364 ± 185/mm3 (P = 0.49) in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively. Similar results were observed at week 48. Moreover, at week 48, 40 and 68% (P = 0.05) and 28 and 59% (P = 0.03) of patients achieved viral suppression at below 200 and 50 copies/ml in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively. At week 24, six patients in the ritonavir group but only one in the ritonavir-saquinavir group had key mutations conferring resistance to protease inhibitors. Clinical and biological tolerances were similar in both groups. In nucleoside analog-pretreated patients, ritonavir-saquinavir has higher antiretroviral efficacy than and is as well tolerated as ritonavir alone.

Highly active antiretroviral therapies including a protease inhibitor sometimes fail to decrease or to maintain viral load below the detection limit, especially in patients heavily pretreated with nucleoside analogs and with multiple key mutations conferring resistance in the reverse transcriptase gene (6, 7, 20). Dual protease inhibitor therapy represents a potent therapeutic alternative for the management of these patients (3, 8). Indeed, pharmacokinetic interactions between protease inhibitors often enhance their bioavailability, allowing dose reductions without any change in antiretroviral activity (3, 13). Moreover, combinations of protease inhibitors are often better tolerated than a single protease inhibitor used at higher doses (3, 14).

Ritonavir, which is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4, has been shown to inhibit saquinavir metabolism in healthy volunteers and in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients (16). When ritonavir (300 mg twice a day [b.i.d.]) was added to saquinavir (600 mg three times a day), the mean maximum plasma saquinavir concentration was increased 30-fold and its median area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 8 h was increased 58-fold (11).

In 1996, a noncomparative pilot study was undertaken to evaluate, in immunocompromised patients, the clinical and biological safety and antiretroviral efficacy of a therapy that combined the protease inhibitors ritonavir and saquinavir with the nucleoside analogs zidovudine and lamivudine (17). This combination was well tolerated and induced high and sustained antiretroviral efficacy. Thus, this research program was continued with a comparative study to evaluate benefit in terms of antiretroviral efficacy, development of key mutations conferring resistance in the protease gene, and tolerance of the combination of ritonavir and saquinavir compared to ritonavir alone in similar patients pretreated with two nucleoside analogs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This study was a multicenter, prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study performed with two parallel groups. A scientific committee met every 3 months to closely monitor the occurrence of serious adverse events and make all relevant decisions about the conduct of the study. This committee allowed recruitment to be started on 21 February 1997 and decided to stop recruitment before reaching the calculated sample size on 28 November 1997. The initial planned duration of the follow-up was 6 months. A first amendment to the protocol (14 March 1997) allowed monitoring of patients during an additional 6-month period to assess long-term antiviral efficacy and the incidence of drug resistance mutations in the protease gene. Therefore, all patients were monitored for up to 48 weeks, whether or not they had stopped their antiretroviral treatment. A critical event validation committee reviewed all adverse events and AIDS-defining events.

The ethics committee of Rennes University Hospital approved the study protocol. All patients gave written informed consent to participate.

Selection criteria.

HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-seropositive adults who had previously been treated with nucleoside analogs for at least 9 months and with zidovudine and lamivudine for the 3 last months were screened for enrollment. Patients were eligible for the study if they had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of >10,000 copies/ml (Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, N.J.) and a CD4 lymphocyte count of <300/mm3 at the time of screening (i.e., 7 to 21 days before inclusion). A second amendment to the protocol (13 June 1997) allowed investigators to include in the study patients who had previously been treated with any combination of two nucleoside analogs for at least 9 months and who had a CD4 lymphocyte count of <500/mm3 at the time of screening.

Patients were excluded if they had a Karnofsky score of <70%, acute major opportunistic infection, severe diarrhea, a hemoglobin level of <9.5 g/dl, a neutrophil count of <750/mm3, a platelet count of <50,000/mm3, hepatic aminotransferase levels >2 times the upper normal levels, alkaline phosphatase levels >3 times the upper normal levels, amylase levels >1.5 times the upper normal levels, lipase levels >1.5 times the upper normal levels, triglyceride levels >2.4 times the upper normal levels, or a serum creatinine level of >150 μmol/liter. Patients were also excluded if they had previously received any HIV-1 protease inhibitor and if they had to be treated with foscarnet (Foscavir), rifampin, or any drug that should not be used with ritonavir.

Treatment regimen.

All patients received the two nucleoside analogs at the doses prescribed before inclusion in the study, ritonavir (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.) at 600 mg b.i.d. and saquinavir (Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) at 400 mg or its placebo (two tablets) b.i.d. Ritonavir was introduced by use of an escalating dose schedule: the starting dose, 300 mg b.i.d., was increased after 2 days to 400 mg b.i.d. for 2 days to reach the target dose at about day 7. Saquinavir was introduced 10 days after ritonavir had been started.

Follow-up.

Times for evaluation were set at weeks from the day of inclusion (day of randomization, corresponding to the day of ritonavir introduction). Patients were assessed at inclusion (baseline), at weeks 2 and 4, and then every 4 weeks from week 4 to week 24 and every 6 weeks from week 24 to week 48. At each visit, patients were interviewed about treatment side effects and compliance. Clinical examinations and standardized laboratory tests were performed. CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte counts were quantified by flow cytometry according to the above-mentioned schedule, except at week 2. After centrifugation, plasma was separated and frozen until used. At week 48, investigators also evaluated body fat distribution abnormalities using a standardized questionnaire.

Evaluation criteria.

The main end point for efficacy was viral load measured at week 24. Secondary efficacy end points included the time courses between inclusion and week 48 for viral load measurements and CD4 lymphocyte counts, the percentage of patients with a viral load below the detection limit, and the occurrence of HIV-1 protease resistance-associated mutations. Secondary safety end points included clinical and biological tolerances assessed using severity levels as defined by the National Institutes of Health (mild, grade 1; moderate, grade 2; severe, grade 3; life-threatening, grade 4), the percentage of patients who had definitely stopped at least one protease inhibitor at week 48, and the percentage of patients who had had at least one AIDS-defining event at week 48.

Plasma protease inhibitor concentrations.

Blood samples were collected at various times after dosing, usually at weeks 4, 12, and 36, for the determination of plasma ritonavir and saquinavir concentrations. Plasma was separated by centrifugation within 0.5 h of blood collection and stored at −20°C. Plasma ritonavir and saquinavir concentrations were measured by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (15). Analyses were performed blindly and serially for each patient at the end of the study at the coordinating center.

Virologic study.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were measured with the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test at inclusion, at week 4, and then every 4 weeks from week 4 to week 24 and every 6 weeks from week 24 to week 48. Plasma samples with a viral load below 200 copies/ml were tested using an ultrasensitive Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test with a detection limit below 50 copies/ml. Analyses were performed blindly and serially for each patient at the end of the study at the coordinating center. Plasma HIV-1 load was also determined during the study at each participating center at week 12 and every 12 weeks up to week 48. In the event of treatment failure, investigators were authorized to modify treatments from week 24. Plasma hepatitis C virus (HCV) load was also determined using the same schedule in patients who were seropositive for this virus at inclusion.

Sequence analysis of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase gene was carried out with plasma at baseline and at week 48. Sequence analysis of the HIV-1 protease gene was carried out with plasma at baseline and at weeks 24 and 48. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with plasma HIV-1 protease resistance-associated mutations were additionally tested at weeks 24 and 48 for HIV-1 protease proviral mutations. HIV-1 RNA was purified from 1 ml of ultracentrifuged plasma (24,000 × g for 1 h) using a Qiamp viral minikit (Qiagen Ltd., Hilden, Germany). For the reverse transcriptase gene analysis, HIV-1 RNA was amplified by one-step reverse transcription-PCR using a Titan one-tube reverse transcription-PCR kit (Boehringer Ltd., Mannheim, Germany) followed by nested PCR with Taq DNA polymerase (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Primers MJ3 and MJ4 were used for the one-step reverse transcription-PCR, and primers A(35) and NE-1(35) were used for the nested PCR. For the protease gene analysis, HIV-1 RNA was retrotranscribed to cDNA by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc., Paisley, Scotland) with antisense primer 3′e-prB followed by PCR and nested PCR with Taq DNA polymerase. Primers 5′e-prB and 3′e-prB were used for the PCR, and primers 5′prB and 3′prB were used for the nested PCR.

DNA was extracted from an aliquot of 3 million peripheral blood mononuclear cells with a whole-blood-specimen-preparation Amplicor HIV-1 kit (Roche Diagnostic Systems). The protease gene was amplified as described above. DNA sequencing was performed at Euro Sequence Genes Services (Evry Génopôle, France) with an ABI 377 sequencer, an ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit, and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. Further analysis and alignments with the HIV-1 reference strain HXB2 were performed with Sequence Navigator software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Sample size and statistical analyses.

The sample size (80 patients) was calculated to be able to detect, with a 90% probability, a difference between groups in viral load at week 24 equal to 0.46 log10 copy/ml (standard deviation [SD] estimated to be 0.70 log10 copy/ml) in a one-sided test performed with a type I error equal to 5%.

All randomized patients were included in the statistical analysis whether or not they had taken their treatments. The analysis was performed with SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). For quantitative variables, the means (and SDs) are reported, whereas for qualitative variables, the number of patients in each category and the corresponding percentages are given. Quantitative variables were compared at baseline using Student's t test and at week 24 using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), the comparison being adjusted to baseline values. The time course of quantitative variables was assessed with a repeated-measures ANCOVA (mixed model), the comparison being adjusted to baseline values. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, when appropriate, was used for categorical variables. For viral load, when the result was below the detection limit, the detection limit of the ultrasensitive test was used for the analysis. For each analysis, a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study description.

Forty-seven patients (25 in the ritonavir group and 22 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) were included in the study at 10 centers from 24 February 1997 to 19 November 1997. Recruitment was stopped before the required sample size was reached because the scientific committee estimated that it had become impossible to treat the patients of the study with only one protease inhibitor (in the placebo group) without simultaneously changing nucleoside analogs. This decision was made because it was thought that changing nucleoside analogs at inclusion could have strongly modified the difference between groups for the main end point. Simultaneously, the scientific committee decided to monitor all the patients already included in the study according to the protocol and to maintain the blindness until the last patient included would have reached week 48. In the event of treatment failure after week 24, the scientific committee advised investigators to treat patients according to what they considered to be the best available treatment at that time without asking for the randomization code. For the other patients, the scientific committee advised investigators to continue the randomized treatment blindly as long as possible.

Study patients.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of study patients at baseline. There was no significant difference between the two groups for any variable except for the duration of previous treatment with lamivudine, which was a little shorter in the ritonavir-saquinavir group than in the ritonavir group (P = 0.05). Most patients had been extensively pretreated with nucleoside analogs (in months: mean and SD, 40 ± 24; median, 39; range, 9 to 89), 42 (89%) of them with zidovudine-lamivudine. In the ritonavir group, the other patients received either zidovudine-didanosine (one patient), zidovudine-dideoxycytidine (one patient), or stavudine-lamivudine (one patient). In the ritonavir-saquinavir group, the other patients received either zidovudine-dideoxycytidine (one patient) or stavudine-didanosine (one patient). Plasma viral load was 4.75 ± 0.56 log10 copies/ml. Fourteen patients (30%) had an HIV-1 load of >100,000 copies/ml. The CD4 cell count was 235 ± 124/mm3. Twenty-one patients (45%) had a CD4 cell count below 200/mm3. Eleven patients (23%) had at least one AIDS-defining event.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the study patients at baseline

| Characteristic | Result for the following group (no. of patients):

|

P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritonavir (25) | Ritonavir + saquinavir (22) | Total (47) | ||

| Age (yr) | 37 ± 9 | 38 ± 10 | 37 ± 9 | 0.92 |

| Weight (kg) | 66 ± 13 | 67 ± 10 | 66 ± 12 | 0.82 |

| Men, no. (%) | 23 (92) | 18 (82) | 41 (87) | 0.40 |

| Homosexual, no. (%) | 15 (60) | 14 (64) | 29 (62) | 0.80 |

| AIDS, no. (%) | 6 (24) | 5 (23) | 11 (23) | 0.92 |

| Previous treatment with zidovudine + lamivudine, no. (%) | 22 (88) | 20 (91) | 42 (89) | 1.00 |

| Previous antiretroviral therapy (mo) | 42 ± 25 | 37 ± 23 | 40 ± 24 | 0.47 |

| with zidovudine | 41 ± 24 | 36 ± 22 | 39 ± 23 | 0.47 |

| with lamivudine | 11 ± 6 | 8 ± 3 | 10 ± 5 | 0.05 |

| Karnofsky score (%) | 96 ± 7 | 94 ± 7 | 95 ± 7 | 0.43 |

| CD4 cell count (/mm3) | 236 ± 126 | 234 ± 125 | 235 ± 124 | 0.96 |

| CD4 count of <200/mm3, no. (%) | 11 (44) | 10 (45) | 21 (45) | 0.92 |

| CD8 cell count (/mm3) | 854 ± 408 | 1004 ± 692 | 926 ± 561 | 0.38 |

| Plasma HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/ml) | 4.75 ± 0.62 | 4.76 ± 0.50 | 4.75 ± 0.56 | 0.95 |

| HIV-1 RNA of >100,000 copies/ml, no. (%) | 7 (28) | 7 (32) | 14 (30) | 0.78 |

| Mutations in reverse transcriptase gene, no. (%)b | ||||

| None | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (5) | |

| Multiple drug resistance profile or 68–69 SS insertion | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | |

| >3 mutations (thymidine analog or M184V) | 13 (59) | 15 (79) | 28 (68) | |

| ≥3 thymidine analog mutations | 13 (59) | 15 (79) | 28 (68) | |

| Mutation M184V | 19 (86) | 15 (79) | 34 (83) | |

| Mutation T69N or L74I | 0 (0) | 3 (16) | 3 (7) | |

The P values correspond to the statistics of Student's t test for quantitative variables and of the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, when appropriate, for categorical variables.

Resistance analysis was performed for 41 patients (22 in the ritonavir group and 19 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) at five predetermined centers. Thymidine analog mutations correspond to mutations at codon 41, 67, 70, 210, 215, and 219.

Resistance analysis at baseline was performed for 41 patients (22 in the ritonavir group and 19 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) at five predetermined centers, as mentioned in the protocol. With regard to the reverse transcriptase gene, two patients (one in each group) did not have any mutation, one patient had a multiple drug resistance profile, and another patient had a 2-bp insert at RT codon 69 (68–69 SS insertion) (the latter two patients were randomized in the ritonavir group). Twenty-eight out of the 37 other patients had more than three nucleoside analog-related reverse transcriptase mutations (13 and 15 patients in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively). There was no mutation conferring resistance to nonnucleoside analogs. With regard to the protease gene, a high degree of polymorphism compared to the HXB2 consensus sequence was observed in our patients prior to protease inhibitor administration.

Follow-up and treatment discontinuation.

All randomized patients completed the 48 weeks of follow-up. At week 48, 19 patients had discontinued randomized treatment (Table 2), 14 (56%) in the ritonavir group and 5 (23%) in the ritonavir-saquinavir group (P = 0.02). Reasons for stopping were side effects in eight patients (four in each group), including three cases of severe hepatitis with a grade 4 alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) increase (these three patients were, at inclusion, coinfected by HCV), treatment failure (a viral load above 1,000 copies/ml) in six patients (all in the ritonavir group), and protocol violation in five patients (four in the ritonavir group and one in the ritonavir-saquinavir group). Protocol violation refers to patients who had stopped randomized treatment before week 48 to take open-labeled saquinavir at 400 mg b.i.d. for no other reason than their own or their physician's decision. Moreover, at week 48, 12 other patients (6 in each group) had experienced ritonavir dose reductions (doses then ranged between 600 and 1,100 mg daily).

TABLE 2.

Reasons for treatment disruption at weeks 24 and 48

| Treatment disruption | No. (%) of patients in the following group at the indicated wk:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritonavir (n = 25)

|

Ritonavir + saquinavir (n = 22)

|

|||

| 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | |

| Total | 3 (12) | 14 (56) | 3 (14) | 5 (23) |

| Related to side effects | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Digestive intolerance | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hepatitis | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Related to treatment failure | 6 | |||

| Related to patient and/or physician decision | 4 | 1 | ||

Plasma protease inhibitor concentrations.

Samples were collected from 0.25 to 16 h after dosing. Ritonavir was detectable in both groups in almost all samples. Undetectable levels were found most of the time in patients who had told the investigators that they had stopped their treatment. Saquinavir was detectable only in the ritonavir-saquinavir group. It was never detectable in the ritonavir group as long as randomized treatment was continued. For patients for whom trough samples were available, ritonavir concentrations ranged between 2.01 and 6.51 μg/ml and saquinavir concentrations ranged between 0.17 and 0.53 μg/ml.

Viral load (antiretroviral) response.

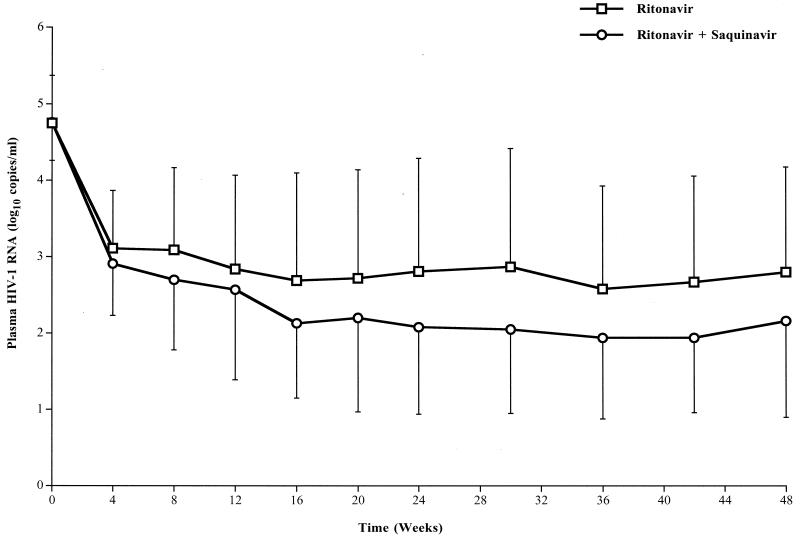

At week 24, in intent to treat analysis, viral load was significantly lower in the ritonavir-saquinavir group than in the ritonavir group (2.08 ± 1.14 versus 2.81 ± 1.48 log10 copies/ml; P = 0.04). Figure 1 shows the time course of the viral load in the two groups from inclusion to week 48. The profiles are significantly different between groups (treatment effect, P = 0.04). The decreases in viral load were quite similar in both groups during the first 4 weeks of treatment. Between weeks 4 and 16, the decrease in viral load continued, but it was more marked in the ritonavir-saquinavir group than in the ritonavir group. From weeks 16 to 48 and despite systematic changes in the entire antiretroviral treatment for patients with treatment failure after week 24, the difference between groups did not change anymore (about 0.7 log10 copy/ml throughout the period). At week 48, viral loads were 2.80 ± 1.38 and 2.16 ± 1.26 log10 copies/ml in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Time course for plasma viral load in the two groups of patients (25 in the ritonavir group and 22 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) during the 48 weeks of follow-up. Data are means, and error bars represent SDs. Results of repeated-measures ANCOVA (mixed-model) analyses were as follows: time effect, P < 0.01; treatment effect, P = 0.04; time-treatment interaction, P = 0.29.

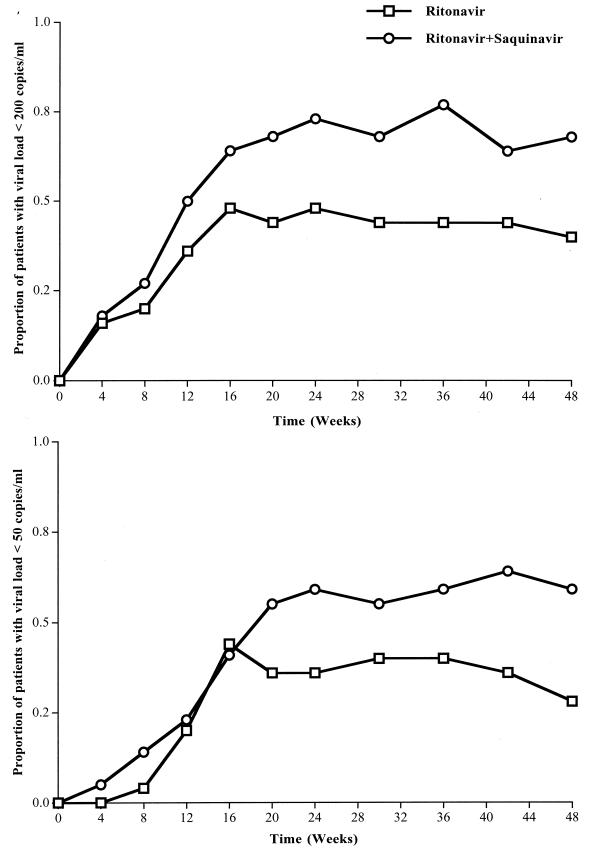

Figure 2 shows the time course for the proportion of patients with viral loads of <200 copies/ml (top plot) and <50 copies/ml (bottom plot) in the two groups from inclusion to week 48. At week 24, the proportion of patients who had HIV-1 RNA levels of <200 copies/ml tended to be higher in the ritonavir-saquinavir group than in the ritonavir group: 16 of 22 (73%) versus 12 of 25 (48%), respectively (P = 0.09). A similar result was obtained for patients who had HIV-1 RNA levels below detectable levels (<50 copies/ml): 13 of 22 (59%) versus 9 of 25 (36%), respectively (P = 0.11). At week 48, the proportions were significantly higher in the ritonavir-saquinavir group than in the ritonavir group: 15 of 22 (68%) versus 10 of 25 (40%), respectively, for the threshold of 200 copies/ml (P = 0.05) and 13 of 22 (59%) versus 7 of 25 (28%), respectively, for the threshold of 50 copies/ml (P = 0.03).

FIG. 2.

Time course for the proportions of patients with viral loads of <200 copies/ml (top) and <50 copies/ml (bottom) in the two groups of patients (25 in the ritonavir group and 22 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) during the 48 weeks of follow-up. Data are percentages. Chi-square test results were as follows: at week 24, P = 0.09 and P = 0.11 for the thresholds of 200 and 50 copies/ml, respectively; at week 48, P = 0.05 and P = 0.03 for the thresholds of 200 and 50 copies/ml, respectively.

Genotypic resistance analysis.

With regard to the reverse transcriptase gene, at week 48, reversion to the wild-type codon was observed in only 1 out of the 16 patients (10 in the ritonavir group and 6 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) for whom amplification was possible in plasma (this patient had stopped antiretroviral treatment for 3 months).

With regard to the protease gene, at week 24, amplification was possible for 26 (16 and 10 in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively) out of the 41 patients. Among these patients, six in the ritonavir group and only one in the ritonavir-saquinavir group had developed key mutations in the protease gene (Table 3). In most of these patients, plasma viral load decreased dramatically during the first month of treatment, but usually it did not reach an undetectable level (below 200 copies/ml), and it increased again towards the baseline value at week 24. At week 48, key mutations in the protease gene were observed in six additional patients, four in the ritonavir group and two in the ritonavir-saquinavir group (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Key mutations in plasma and cells, time course of viral load, and treatment at week 48a

| Group | Patient | Key mutations at the indicated wk in:

|

Viral load (log10 copies/ml)

|

Treatment at wk 48 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma

|

Cells

|

|||||||||

| 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | At inclusion | Δmax (time, wk) | At wk

|

||||

| 24 | 48 | |||||||||

| Ritonavir | 1001 | V82A, I54V | V82A, I54V | None | I54I/V | 4.67 | −2.89 (4) | 3.98 | <1.30 | D4t, N, S∗ |

| 2005 | NA | V82F | None | None | 4.41 | −2.48 (16) | 1.94 | 2.34 | D4t, L, I | |

| 3004 | V82A, L90M, I54V | V82A, L90M, I54V | None | V82V/A, L90L/M, I54I/V | 6.18 | −2.09 (4) | 5.67 | 5.54 | Z, L, R | |

| 3007 | None | V82A | NA | None | 4.89 | −2.25 (20) | 2.91 | 2.70 | Z, Ddc, R, S | |

| 4005 | None | V82F, L90M | NA | V82V/F | 5.71 | −3.21 (20) | 2.65 | 4.78 | Z, L, R | |

| 4007 | V82S, I54V | V82S, I54V | NA | NA | 4.85 | −2.38 (4) | 4.65 | 3.80 | D4t, L, N, S∗ | |

| 4012 | V82A | V82A | None | None | 4.74 | −2.58 (24) | 2.16 | 2.61 | Z, L, R, S | |

| 4013 | NA | V82A, I84V | None | None | 4.14 | −2.84 (16) | <1.30 | 3.27 | Z, L, R, S | |

| 4019 | V82A, I54V | V82A, I54V L90M | None | None | 4.23 | −1.13 (4) | 3.93 | 4.55 | Z, Ddi, R, S | |

| 10002 | V82A, L90M, I54I/V | NA | None | NA | 5.56 | −1.30 (4) | 5.41 | 5.50 | D4t, Ddi, N, S∗ | |

| Saquinavir | 1004 | NA | G48V | NA | NA | 4.49 | −3.19 (16) | <1.30 | 3.87 | Z, L, S∗ |

| 2001 | I84V | I84V | None | None | 5.65 | −3.18 (16) | 2.57 | 2.45 | Z, L, R, S | |

| 4009 | None | V82A, I84V | NA | None | 5.30 | −3.07 (12) | 4.11 | 2.43 | Z, L, R, S | |

NA, not amplified. Δmax, maximum change from inclusion. Z, zidovudine; L, lamivudine; D4t, stavudine; Ddc, dideoxycytidine; Ddi, didanosine; R, ritonavir; S, saquinavir (or placebo); S∗, open-labeled saquinavir; I, indinavir; N, nelfinavir. Amino acid mixtures (i.e., mixtures of wild-type and mutant HIV amino acids) are indicated in italics.

At week 24 (for eight patients), no mutation conferring resistance to protease inhibitors was found in peripheral blood mononuclear cell proviral DNA. At week 48 (for 10 patients), mutations were found in three out of the eight and in none of the two patients for whom the protease gene could be amplified in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively. The amino acid substitutions were I54V in one patient, V82A-L90M-I54V in another one, and V82F in the third one (Table 3).

Immunologic survey.

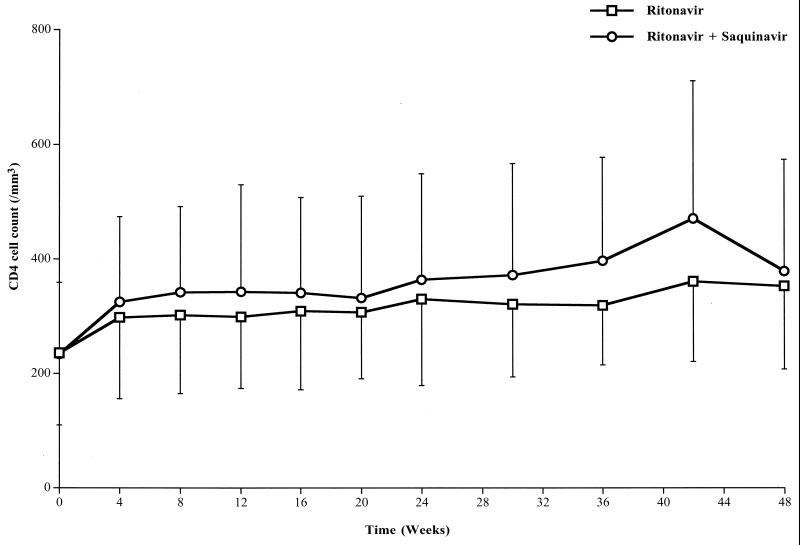

Figure 3 shows the time course for the CD4 cell counts in the two groups from inclusion to week 48. The CD4 cell counts significantly increased in both groups (time effect, P = 0.01), but without a significant difference between groups (treatment effect, P = 0.17). CD4 cell counts were 330 ± 151 and 364 ± 185/mm3 (P = 0.49) at week 24 and 353 ± 145 and 379 ± 195/mm3 at week 48 in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Time course for CD4 cell counts in the two groups of patients (25 in the ritonavir group and 22 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) during the 48 weeks of follow-up. Data are means, and error bars represent SDs. Results of repeated-measures ANCOVA (mixed-model) analyses were as follows: time effect, P = 0.01; treatment effect, P = 0.17; time-treatment interaction, P = 0.51.

AIDS-defining events.

During the 48 weeks of follow-up, only one patient (in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) had an AIDS-defining event. It was an anal carcinoma diagnosed at week 48. Four patients (three and one in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively) had other types of events: oral candidiasis (three patients) and zoster infection (one patient). At week 48, all included patients were alive.

Adverse events.

There was no significant difference between groups with regard to the occurrence of each clinical adverse event or biological change. The main clinical adverse events in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively, were diarrhea in 15 and 16 patients (P = 0.36), including at least grade 2 events in 4 patients in each group; nausea in 7 and 7 patients (P = 0.78), including at least grade 2 events in 1 and 5 patients (P = 0.09); vomitus in 4 and 2 patients (P = 0.67); asthenia in 10 and 4 patients (P = 0.10); circumoral paresthesia in 13 and 10 patients (P = 0.65); peripheral paresthesia in 4 and 4 patients (P = 1.00); dysgeusia in 7 and 6 patients (P = 0.96); and hot flushes in 3 and 4 patients (P = 0.69).

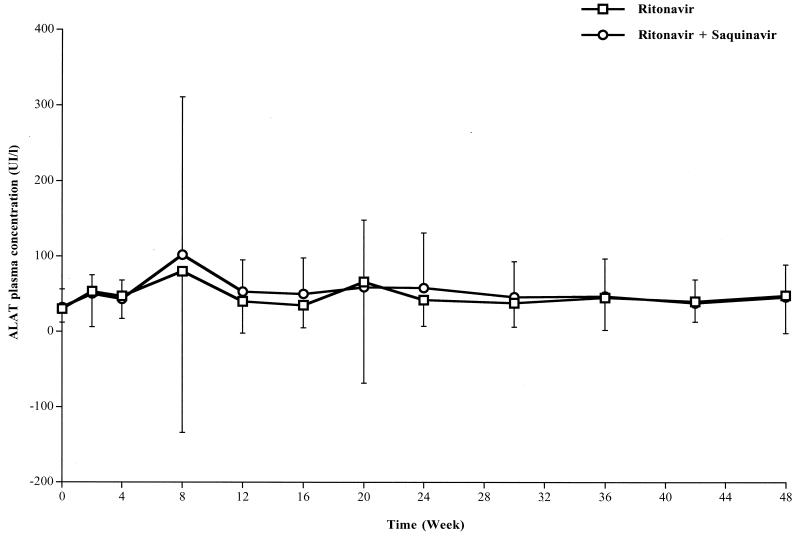

The main biological side effects are reported in Table 4. Triglyceride and/or cholesterol increases did not induce any clinical consequences during the 48 weeks of follow-up, and no major change in body fat distribution was observed (i.e., no major lipoatrophy of the face and no abdominal or neck fat accumulation). Plasma hepatic amino transferase (ALAT) levels increased in 15 and 16 patients, including at least grade 2 events in 7 and 5 patients, in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively. This increase was transient, the peak of ALAT being observed at week 8 (Fig. 4). Three out of these 12 patients had more than 10-fold increases in ALAT levels (grade 4) and had to stop ritonavir and saquinavir (or its placebo). One patient had received ritonavir alone, and the other two had received ritonavir-saquinavir (Table 2). These three patients were coinfected with HCV, and the mean HCV load increased from 5.78 ± 0.37 (at inclusion) to 6.68 ± 0.34 (at week 4) log10 copies/ml. An attempt to reintroduce ritonavir 1 to 3 months after stopping it and after a decrease in ALAT levels induced a new increase in ALAT levels in the three patients at week 20 (Fig. 4). Four other patients included in the study were coinfected with HCV. They had only mild and transient increases in ALAT levels. In these patients, the HCV load did not really change during the first 6 months of treatment (from 5.63 ± 0.67 [at inclusion] to 5.53 ± 0.69 [at week 24] log10 copies/ml).

TABLE 4.

Main biological side effects

| Side effect | Result for the following group (no. of patients):

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ritonavir (25) | Ritonavir + saquinavir (22) | ||

| Triglyceride increaseb, no. (%) | 23 (92) | 20 (91) | 1.00 |

| Mean ± SD at baseline (mmol/liter) | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 0.32 |

| Range at baseline (mmol/liter) | 0.6–8.1 | 0.5–5.8 | |

| Mean ± SD at wk 24 (mmol/liter) | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 3.2 | 0.88 |

| Range at wk 24 (mmol/liter) | 0.9–7.4 | 0.8–13.1 | |

| Cholesterol increaseb, no. (%) | 7 (28) | 6 (27) | 0.96 |

| Mean ± SD at baseline (mmol/liter) | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 0.09 |

| Range at baseline (mmol/liter) | 3.5–6.7 | 2.5–6.6 | |

| Mean ± SD at wk 24 (mmol/liter) | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 0.39 |

| Range at wk 24 (mmol/liter) | 4.4–10.4 | 4.2–8.8 | |

| ALAT increasec, no. (%) | |||

| Overall | 15 (60) | 16 (73) | 0.36 |

| At least grade 2 | 7 (28) | 5 (23) | 0.68 |

| ASAT increased, no. (%) | |||

| Overall | 10 (40) | 10 (45) | 0.71 |

| At least grade 2 | 3 (12) | 4 (18) | 0.69 |

| Glutamyl transpeptidase increase, no. (%) | |||

| Overall | 19 (76) | 16 (73) | 0.80 |

| At least grade 2 | 11 (44) | 10 (45) | 0.92 |

The P values correspond to the statistics of Student's t test (baseline values) and of ANCOVA (week 24 values, the comparison being adjusted to baseline values) for quantitative variables and of the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, when appropriate, for categorical variables.

Lipid measurements were not always obtained in a fasting state. However, to limit intraindividual variations, blood samples were collected for each patient at similar times along the follow-up and thus at similar intervals after food intake.

ALAT, alanine aminotransferase.

ASAT, aspartate aminotransferase.

FIG. 4.

Time course for plasma hepatic aminotransferase (ALAT) levels in the two groups of patients (25 in the ritonavir group and 22 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) during the 48 weeks of follow-up. Data are means, and error bars represent SDs. Results of repeated-measures ANCOVA (mixed-model) analyses were as follows: time effect, P < 0.01; treatment effect, P = 0.73; time-treatment interaction, P = 0.70. UI, international units.

DISCUSSION

The study was designed early in 1996, after it was reported that the addition of ritonavir to previous treatment with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors had a strong but only transient effect on viral load in severely immunocompromised patients with high plasma viral loads (2). The recruitment was stopped by the scientific committee when it became possible to propose alternative reverse transcriptase inhibitors and when it was clearly demonstrated that the change in nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors at the initiation of protease inhibitor treatment exerted a stronger and more prolonged antiretroviral effect than the addition of a protease inhibitor alone (10). Simultaneously, the scientific committee advised investigators to continue the follow-up of patients already included in the study, since the question of efficacy of dual protease inhibitors was still open and there was no better formal therapeutic alternative for these patients. This experience emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring of study designs in eras of rapidly evolving therapeutic approaches, such as that for HIV infection.

Since we used a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind design with intent-to-treat analysis, our study definitely proves that the combination of ritonavir and saquinavir has antiretroviral additive effects. Indeed, all the previously published studies on that topic were either noncomparative (9, 19) or were randomized but nonblinded ones (14). Moreover, we used a high dosage of ritonavir (600 mg b.i.d.), which is no longer being used in combination with saquinavir or other protease inhibitors in the treatment of HIV-1-infected patients (4). In practice, our study demonstrates that the dual protease inhibitor regimen of ritonavir at 600 mg b.i.d. and saquinavir at 400 mg b.i.d. has stronger antiviral efficacy than ritonavir at 600 mg b.i.d. alone after 24 and even 48 weeks of treatment. At week 24, a significant difference of 0.7 log10 copy/ml was observed between the two groups, and this difference was maintained at 48 weeks of follow-up. A significant difference of 31% was also observed at week 48 between the two groups of patients with undetectable HIV-1 RNA levels. These results were obtained for patients with high viral loads (4.75 ± 0.56 log10 copies/ml) and low CD4 cell counts (45% of patients had CD4 cell counts of <200/mm3), without any change in nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors at inclusion and despite large treatment changes (concerning both nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors) in the event of treatment failure at week 24 in the ritonavir group.

Factors associated with treatment failure were analyzed for the 19 patients (13 in the ritonavir group and 6 in the ritonavir-saquinavir group) who had HIV-1 RNA levels of ≥200 copies/ml at week 24. In the ritonavir group, 10 patients were tested for genotypic resistance: 5 had developed key resistance mutations in the protease gene which were detected after viral load rebound. Among the other five patients, one had definitely stopped treatment and another had been poorly compliant. The three remaining patients were still on full doses of ritonavir at week 24 and could be considered compliant, as suggested by the expected levels of plasma ritonavir concentrations and the strong decrease in viral loads between baseline and week 24 (viral loads of <1,000 copies/ml at week 20 for the three patients). In the ritonavir-saquinavir group, the six patients were tested for genotypic resistance: only one had developed a key resistance mutation in the protease gene. Among the other five patients, two had definitely stopped treatment and two others had been poorly compliant. The last patient was still on full doses of ritonavir at week 24 and could be considered compliant, as suggested by the high plasma ritonavir concentration and the strong decrease in viral load between baseline and week 24. In fact, for this patient, the increase in the plasma HIV-1 RNA level at week 24 (202 copies/ml) was only transient and was not seen again later (123 copies/ml at week 48).

The better antiviral efficacy of the dual protease inhibitor regimen was associated with a strong reduction in the emergence of key mutations conferring resistance to protease inhibitors both in plasma and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. At week 24, primary mutations were already detectable in the plasma of six and one patients in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively, but they were never detectable in HIV-1 proviral DNA at that time. At week 48, these mutations were found in the plasma of nine and three patients in the ritonavir and ritonavir-saquinavir groups, respectively, and in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of three patients in the ritonavir group. Thus, in the ritonavir group, the occurrence of key resistance mutations in HIV-1 proviral DNA was delayed compared to the emergence of similar mutations in plasma HIV-1 RNA, as previously reported for zidovudine (12). In the ritonavir-saquinavir group, no mutation was found on HIV-1 proviral DNA extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. These results also strongly argue in favor of the dual protease inhibitor regimen.

In contrast to the strong differences between groups in antiretroviral effects, both treatments similarly increased CD4 cell counts. In fact, the profile obtained for the ritonavir-saquinavir group was always slightly higher than that obtained for the ritonavir group. The difference, which was on average equal to +43/mm3, was detectable as early as week 4 (+27/mm3) and was maintained up to week 48 (+26/mm3) but probably was insufficient to be significant. These results indicate that in the ritonavir group, the highest treatment failure rate observed during follow-up had no major consequence on the evolution over time of CD4 cell counts. This finding might question deferring treatment modification when an undetectable viral load is not reached and CD4 cell counts remain stable and are apparently well preserved. Indeed, this action must be balanced against the risk of resistance mutation accumulation in the presence of ongoing viral replication.

Clinical and biological tolerances were, for most variables, not significantly different between the two groups. Moreover, the proportions of patients who had stopped randomized treatment at week 24 (early disruptions in relation to side effects) were similar in the two groups and were lower than the proportions previously reported with ritonavir at 600 mg b.i.d. alone (14). In fact, the proportion of treatment disruptions was quite close to that reported with ritonavir at 400 mg b.i.d. (2, 19). We observed strong increases in triglyceride levels in almost all patients in both groups, which were associated in 28% of the patients with mild cholesterol increases. These increases were similar in both groups. In contrast to the high percentage of lipodystrophy reported in other studies with ritonavir and saquinavir in combination (5), we did not observe clinically detectable lipoatrophy in our patients. We have no real explanation for this result apart from the relatively short duration of protease inhibitor treatment and/or the lack of change in nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors at inclusion (considering the hypothesis of a relationship between mitochondrial cytopathic effects induced by these drugs and lipoatrophy) (1). Indeed, although the detection and follow-up of lypodystrophy were not initially planned by the protocol, all patients were seen at week 48 to evaluate body fat distribution abnormalities. Finally, large proportions of patients had ALAT increases, which were similar in the two groups. Moreover, all patients who had ALAT increases of at least grade 2 were coinfected with HCV and experienced HCV load increases. This result confirms that ritonavir must be used with great caution in patients who are coinfected with HCV, despite the possible favorable effect of this drug on the evolution of chronic hepatitis C (18).

In conclusion, our study shows that the combination of the protease inhibitors ritonavir and saquinavir induces high and prolonged decreases in viral loads, prevents the development of key mutations conferring resistance in the protease gene, and is at least as well tolerated as ritonavir alone. In contrast, the two regimens induced similar effects on CD4 cell counts and this result encourages further studies to evaluate the trade-off between ongoing viral replication under a failing regimen and satisfying CD4 cell count evolution.

These results were obtained with high doses of ritonavir and cannot be applied, without formal demonstration, to the lower doses of ritonavir currently used to boost other protease inhibitors. Finally, this experience emphasizes the need for close monitoring of ongoing studies in order to stop recruitment following new therapeutic advances.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS), Paris, Laboratoire Abbott, Rungis, and Laboratoire Roche, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.

We thank all participating investigators; the locations of the clinical centers (investigators) participating in the study were as follows: Avignon (G. Lepeu), Bicêtre (J.-F. Delfraissy and F. Couetil), Bordeaux (D. Lacoste, P. Morlat, and J.-M. Ragnaud), Caen (C. Bazin and M. Six), La Rochesor Yon (P. Perre), Nantes (F. Raffi and E. Billaud), Perpétuel Secours (G. Force), Rennes (F. Cartier), Rouen (F. Caron), and Toulouse (P. Massip). We thank Jean Dormont for helpful suggestions during the study design; Cecile Stagnetto, Caroline Jamois, and Christelle Tual for monitoring; Habiba Mesbah for data management; Olivier Tribut, Marie-Françoise Mordelet, and Danielle Bentue-Ferrer for plasma ritonavir-saquinavir level determinations; and Odile Guist'hau, Laurence Havard, and Jeanine Gicquel for help in the virologic study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brinkman K, ter Hofstede H J, Burger D M, Smeitink J A, Koopmans P P. Adverse effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors: mitochondrial toxicity as common pathway. AIDS. 1998;12:1735–1744. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron D W, Heath-Chiozzi M, Danner S, Cohen C, Kravcik S, Maurath C, Sun E, Henry D, Rode R, Potthoff A, Leonard J M. Randomized placebo controlled trial of ritonavir in advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet. 1998;351:543–549. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron D W, Japour A J, Xu Y, Hsu A, Mellors J, Farthing C, Cohen C, Poretz D, Markowitz M, Follansbee S, Angel J B, McMahon D, Ho D, Devanarayan V, Rode R, Salgo M, Kempf D J, Granneman R, Leonard J M, Sun E. Ritonavir and saquinavir combination therapy for the treatment of HIV infection. AIDS. 1999;13:213–224. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter C C, Cooper D A, Fischl M A, Gatell J M, Hammer S M, Hirsch M S, Jacobsen D M, Katzenstein D A, Montaner J S, Richman D D, Saag M S, Schechter M, Schooley R T, Thompson M A, Vella S, Yeni P G, Volberding P A. Antiretroviral therapy in adults: updated recommendations of the international AIDS society-USA panel. JAMA. 2000;283:381–390. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr A, Samaras K, Burton S, Law M, Freund J, Chisholm D J, Cooper D A. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1998;12:F51–F58. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGruttola V, Dix L, D'Aquila R, Holder D, Phillips A, Ait-Khaled M, Baxter J, Clevenbergh P, Hammer S, Harrigan R, Katzenstein D, Lanier R, Miller M, Para M, Yerly S, Zolopa A, Murray J, Patick A, Miller V, Castillo S, Pedneault L, Mellors J. The relation between baseline HIV drug resistance and response to antiretroviral therapy: re-analysis of retrospective and prospective studies using a standardized data analysis plan. Antiviral Ther. 2000;5:41–48. doi: 10.1177/135965350000500112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fätkenheuer G, Theisen A, Rockstroh J, Grabow T, Wicke C, Becker K, Wieland U, Pfister H, Hegener P, Franzen C, Schwenk A, Salzberger B. Virological treatment failure of protease inhibitor therapy in an unselected cohort of HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1997;11:F113–F116. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199714000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flexner C. Dual protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients: pharmacologic rationale and clinical benefits. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gisolf E H, Jurriaans S, Pelgrom J, van Wanzeele F, van der Ende M E, Brinkman K, Borst M J, de Wolf F, Japour A J, Danner S A. The effect of treatment intensification in HIV-infection: a study comparing treatment with ritonavir/saquinavir and ritonavir/saquinavir/stavudine. AIDS. 2000;14:405–413. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulick R M, Mellors J W, Havlir D, Eron J J, Gonzales C, McMahon D, Richman D D, Valentine F T, Jonas L, Meibohn A, Emini E A, Chodakewitz J A. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamuvidine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu A, Granneman G R, Cao G, Carothers L, El-Shourbagy T, Baroldi P, Erdman K, Brown F, Sun E, Leonard J M. Pharmacokinetic interactions between two human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors ritonavir and saquinavir. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:453–464. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaye S, Comber E, Tenant-Flowers M, Loveday C. The appearance of drug resistance-associated point mutations in HIV type 1 plasma RNA precedes their appearance in proviral DNA. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:1221–1225. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kempf D J, Marsh K C, Kumar G, Rodrigues A D, Denissen J F, McDonald E, Kukulka M J, Hsu A, Granneman G R, Baroldi P A, Sun E, Pizzuti D, Plattner J J, Norbeck D W, Leonard J M. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus protease by coadministration with ritonavir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:654–660. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirk O, Katzenstein T L, Gerstoft J, Mathiesen L, Nielsen H, Pedersen C, Lundgren J D. Combination therapy containing ritonavir plus saquinavir has superior short-term antiretroviral efficacy: a randomized trial. AIDS. 1999;13:F9–F16. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh K C, Eidem E, McDonald E. Determination of ritonavir, a new HIV protease inhibitor, in biological samples using reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. J Chomatogr Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;704:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merry C, Barry M G, Mulcahy F, Ryan M, Heavey J, Tjia J F, Gibbons S E, Breckenridge A M, Back D J. Saquinavir pharmacokinetics alone and in combination with ritonavir in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1997;11:F29–F33. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michelet C, Bellissant E, Ruffault A, Arvieux C, Delfraissy J F, Raffi F, Bazin C, Renard I, Sebille V, Chauvin J-P, Dohin E, Cartier F. Safety and efficacy of ritonavir and saquinavir in combination with zidovudine and lamuvidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65:661–671. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michelet C, Chapplain J-M, Petsaris O, Arvieux C, Ruffault A, Lotteau V, André P. Differential effect of ritonavir and indinavir on immune response to hepatitis C virus in HIV-1 infected patients. AIDS. 1999;13:1995–1996. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhone S A, Hogg R S, Yip B, Sherlock C, Conway B, Schechter M T, O'Shaughnessy M V, Montaner J S. The antiviral effect of ritonavir and saquinavir in combination amongst HIV-infected adults: results from a community-based study. AIDS. 1998;12:619–624. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199806000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wit F W, van Leeuwen R, Weverling G J, Jurriaans S, Nauta K, Steingrover R, Schuijtemaker J, Eyssen X, Fortuin D, Weeda M, de Wolf F, Reiss P, Danner S A, Lange J M. Outcome and predictors of failure of highly active antiretroviral therapy: one-year follow-up of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:790–798. doi: 10.1086/314675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]