ABSTRACT

The B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has contributed to a new increment in cases across the globe. We conducted a prospective follow-up of COVID-19 cases to explore the recurrence and potential propagation risk of the Delta variant and discuss potential explanations for the infection recurrence. A prospective, non-interventional follow-up of discharged patients who had SARS-CoV-2 infections by the Delta variant in Guangdong, China, from May 2021 to June 2021 was conducted. The subjects were asked to complete a physical health examination and undergo nucleic acid testing and antibody detection for the laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19. In total, 20.33% (25/123) of patients exhibited recurrent positive results after discharge. All patients with infection recurrence were asymptomatic and showed no abnormalities in the pulmonary computed tomography. The time from discharge to the recurrent positive testing was usually between 1-33 days, with a mean time of 9.36 days. The cycle threshold from the real-time polymerase chain reaction assay that detected the recurrence of positivity ranged from 27.48 to 39.00, with an average of 35.30. The proportion of vaccination in the non-recurrent group was higher than that in the recurrently positive group (26% vs. 4%; χ2 = 7.902; P < 0.05). Two months after discharge, the most common symptom was hair loss and 59.6% of patients had no long-term symptoms at all. It is possible for the Delta variant SARS-CoV-2 patients after discharge to show recurrent positive results of nucleic acid detection; however, there is a low risk of continuous community transmission. Both, the physical and mental quality of life of discharged patients were significantly affected. Our results suggest that it makes sense to implement mass vaccination against the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Follow-up survey, Delta variant

INTRODUCTION

At the end of December 2019, a group of patients infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) were detected in Wuhan, China 1 . This outbreak represented the beginning of a significant global public health issue, leading to a worldwide pandemic due to the significant infectivity and virulence of this virus 2,3 . Globally, as of September 22, 2021, there were 229,373,963 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 4,705,111 deaths, reported to the World Health Organization. China has confirmed more than 120,000 infections and more than 5,000 deaths. Through concerted efforts, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been gradually and effectively controlled in China by adopting a series of strict intervention measures, including social distancing, vaccination and community management to block local outbreaks 4 . In particular, the widespread use of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs, such as lopinavi and ritonavirhas achieved some satisfactory results 5 .

Many clinical studies have been committed to the measurement of epidemiological and clinical features in the acute phase of COVID-19 6,7 . However, only a small number of studies on follow-up data from discharged patients have been reported. The follow-up of patients after discharge plays an important role in promoting the improvement of current diagnosis and treatment protocols. Furthermore, continuous quarantine and community follow-up of discharged patients is a fundamental measure to reduce the risk of disease recurrence leading to the spread of the pandemic. Previous studies have reported that the proportion of recurrence among discharged patients was 2.4% to 69.2%, with the potential for recurrence persisting for 1 to 38 days after discharge 8 .

The B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant was identified in India in December 2020, and it has quickly swept across approximately 80 countries, resulting in a large number of cases due to its higher infectivity and virulence. On May 21, 2021, in Guangzhou, China, an elderly woman with COVID-19 was confirmed to be a carrier of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 through a virological surveillance and sequencing of amplification products. Subsequently, a large number of cases were diagnosed, with a total of 153 cases confirmed in this outbreak. However, many patients have met the hospital discharge criteria and are now gradually returning to the community life. We believe that certain strategies, such as the implementation of physical health examinations, nucleic acid detection and antibody measurements starting at the time of discharge are necessary for a long-term follow-up, especially for patients carrying mutant variants of the virus.

In this study, we aimed to conduct a medical observation during the follow-up of COVID-19 patients by the Delta variant after discharge to summarize the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of discharged patients and to discuss the potential explanations for the viral recurrence and the degree of contagiousness of patients with recurrent positive viral detection. . These findings should aid in the management of patients with COVID-19 caused by the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 after their hospital discharge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital. Study subjects (and their parents or guardians if the patient was a minor) provided informed consents prior to enrollment in the study. The procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective and non-interventional follow-up of patients reported to have a form of pneumonia attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 outbreak in Guangzhou (23°N,113°E) from May to June 2021. Eligible subjects were those who had been previously diagnosed with COVID-19, and their respiratory specimens were submitted to sequencing, with the final results showing that all viruses were Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2.

The patients were treated at the Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China. Patients were discharged after two negative nucleic acid tests, performed at least 24 h apart, and after clinical recovery according to the China National Health and Fitness Commission criteria. Patients were also isolated for 14 days during hospitalization before returning to the community.

In-hospital data collection

The clinical outcome of acute-phase disease in all 123 patients initially enrolled were available and analyzed retrospectively. All clinical data from the acute phase, including epidemiological characteristics and clinical signs and symptoms, were collected from the Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital electronic medical records system. Demographic information (age, sex, comorbidity, smoking history), SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (date and dose of vaccine), and baseline clinical characteristics (symptoms, severity classification, date of onset and discharge) were collected.

Follow-up after discharge

A total of 123 patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 were designated as the study subjects after discharge. These individuals were distributed across six districts of Guangzhou, including Liwan District (n = 108), Nansha District (n = 6), Haizhu District (n = 5), Panyu District (n = 2), Yuexiu District (n = 1), and one in Baiyun District (n = 1). The first case included in this study was discharged on June 26, 2021, and the last case was discharged on August 23, 2021.

Patients were followed-up for up to four months after hospital discharge, and repeated nucleic acid and antibody tests as well as physical examinations. Nucleic acid detection was performed on days 1, 7, 14, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 after discharge, while antibody examinations on days 7, 14, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 and physical examinations on days 14, 30, 45 and 60, respectively. When the SARS-CoV-2 test result was positive, the follow-up was immediately ended and restarted again after the new discharge.

Assessment of symptoms during the follow-up

The following symptoms were recorded on a structured paper questionnaire during the follow-up: fever, dry cough, fatigue, loss of smell and taste, nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, conjunctivitis, myalgia and diarrhea. In addition, other subjective symptoms were investigated, including decreased physical activity, concentration problems, insomnia, anxiety, heart palpitations, hair loss and poor appetite.

Laboratory methods during the follow-up

Laboratory testing was conducted at an accredited Guangzhou Center for Disease Control laboratory using standard operating procedures in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Infected persons were identified as being infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 by a real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. Patients whose cycle threshold was 40 or less were considered to be positive for infection (Wuhan EasyDiagnosis Biomedicine Co., China). Serum-specific IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were detected using the COVID-19 Antibody (Immunoglobulin [Ig]M/IgG) Detection Kit (Autobio, China) using 206 samples by ROC curve Statistical Analysis. We set the highest point of the Youden index (sensitivity 90%, specificity 100%) to determine the cut off coefficient as 0.1, that is, the positive judgment value (cut off value) of the kit is the average luminescence value of the positive control well*0.1.The S/CO value is the ratio of the luminescence value of the sample to be tested to the cutoff value. If it is greater than or equal to 1, it is judged to be positive. Conversely, if it is less than 1, it is judged as negative.

Data analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation values and the differences between groups were evaluated using the t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequency (n) and relative frequency (%) values, and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and a two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic information of patients

A total of 123 patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 completed the clinical follow-up. These patients were aged 2-85 years of age, with an average of 47.48 years. The demographic information of these patients is presented in Table 1 showing that most participants were female (59.35%) and younger than 60 years of age (66.67%). More than half of the study participants had no underlying disease (59.35%), and most infected individuals had not been vaccinated before hospital admission (73.98%).

Table 1. Patients who recovered from the COVID-19 Delta variant according to demographic data.

| Characteristics | Number | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 50 | 40.65 |

| Female | 73 | 59.35 | |

| Age (in years) | <60 | 82 | 66.67 |

| ≥60 | 41 | 33.33 | |

| Vaccination | Not vaccinated | 91 | 73.98 |

| First dose | 20 | 16.26 | |

| Second dose | 12 | 9.76 | |

| Comorbidity | Yes | 50 | 40.65 |

| No | 73 | 59.35 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 14 | 11.38 |

| No | 109 | 88.62 |

Baseline clinical features at illness onset

At the onset of illness, the leading symptom was fever (45.53%), followed by cough (44.72%). Other symptoms included dry throat (27.64%), sore throat (11.38%) and expectoration (10.57%). Individuals with moderate severity of the disease accounted for 75.61% of the cases.

Nucleic acid detection and antibody examination during the follow-up visits

The 123 study participants completed one to six nucleic acid testing during the follow-up monitoring period, and 563 nucleic acid samplings were completed in total for this study.

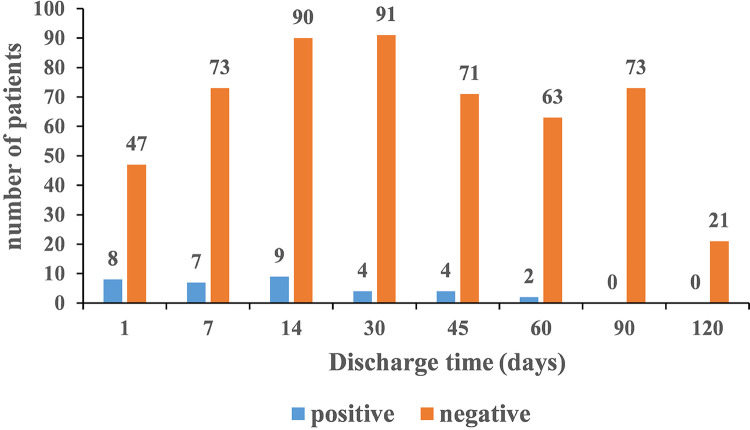

Specifically, 55 infected persons completed the nucleic acid tests on the first day after discharge, of which 8 were positive and 47 were negative. On the seventh day after discharge, 7 of 80 patients were positive. On the 14th day after discharge, 9 of 99 patients were positive. On the 30th day after discharge, 4 of 95 patients were positive. On the 45th day after discharge, 4 of 75 patients were positive. On the 60th day after discharge, 2 of 65 patients were positive. Finally, on the 90th and 120th days after discharge, all previously infected persons tested negative.

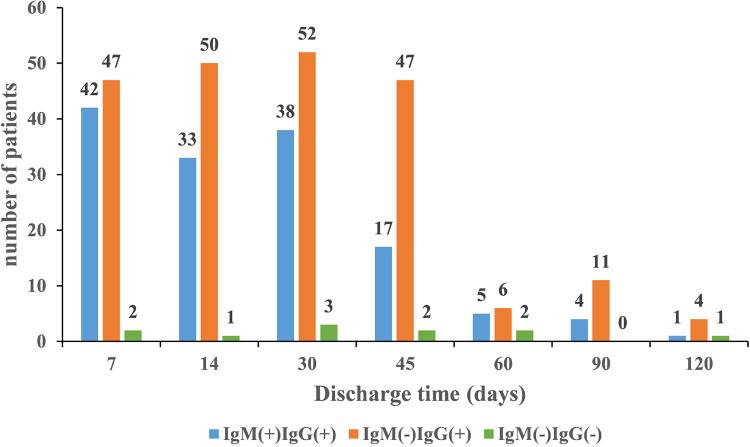

On the seventh day after discharge, 42 of 91 patients were positive for both IgM and IgG antibodies, 47 were negative for IgM antibodies and positive for IgG antibodies, and two were negative for both, IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. On the 14th day after discharge, 33 of 84 patients were positive for both IgM and IgG antibodies, 50 were negative for IgM antibodies and positive for IgG antibodies, and one was negative for both IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. On the 30th day after discharge, 38 of 93 patients were positive for both, IgM and IgG antibodies, 52 were negative for IgM and positive for IgG antibodies, and three were negative for both, IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. On the 45th day after discharge, 17 of 66 patients were positive for both, IgM and IgG antibodies, 47 were negative for IgM and positive for IgG antibodies, and two were negative for both, IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. On the 60th day after discharge, 5 of 13 patients were positive for both, IgM and IgG antibodies, 6 were negative for IgM and positive for IgG antibodies, and 2 were negative for both IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. On the 90thday after discharge, 4 of 15 patients were positive for both, IgM and IgG antibodies, 11 were negative for IgM and positive for IgG antibodies. On the 120th day after discharge, 1 of 6 patients was positive for both, IgM and IgG antibodies, 4 were negative for IgM and positive for IgG antibodies, and one was negative for both, IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, respectively. The results of the nucleic acid and serum antibody tests performed during the follow-up visits are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. RT-PCR results of patients during follow-up visits. On the X-axis, the discharge time in days and on the Y-axis, the number of copies of the RT-PCR target gene expressed in number of copies/reaction.

Figure 2. Results of serum IgM/IgG antibody testing performed during follow-up visits. On the X-axis, the discharge time in days and on the Y-axis, the antibody title expressed in AU/mL (arbitrary units/mL).

Demographic characteristics of patients with infection recurrence

Twenty-five of the 123 patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 tested positive for respiratory SARS-CoV-2 after discharge, with a recurrent positivity rate of 20.33% (25/123).

The patients with infection recurrence ranged in age from 2-84 years, with an average age of 47.76 years. Most cases were female (72.00%) and unvaccinated (96.00%). Participants who were younger than 60 years of age accounted for 60.00% of the recurrent positive group. It is worth noting that all recurrently positive cases were confirmed cases and all patients with infection recurrence were re-admitted to the hospital.

In addition, a total of 5 close contacts and 266 key populations were screened, and following a close observation, none of them developed the disease.

Laboratory results of patients with infection recurrence

The first recurrently positive case included in this study was detected on June 27, 2021, and the last case was detected on August 27, 2021. The time between confirmation of a recurrent positive case and discharge was generally between 1-33 days. The average time from discharge to the new positive test for SARS-CoV-2 was approximately 9.36 days.

The cycle threshold of RT-PCR assay for the recurrent positive cases was less than 33 (27.48–28.54) in two of these cases and greater than 33 (33.15–39.00) in the other 23 cases, and the average cycle threshold was 35.30.

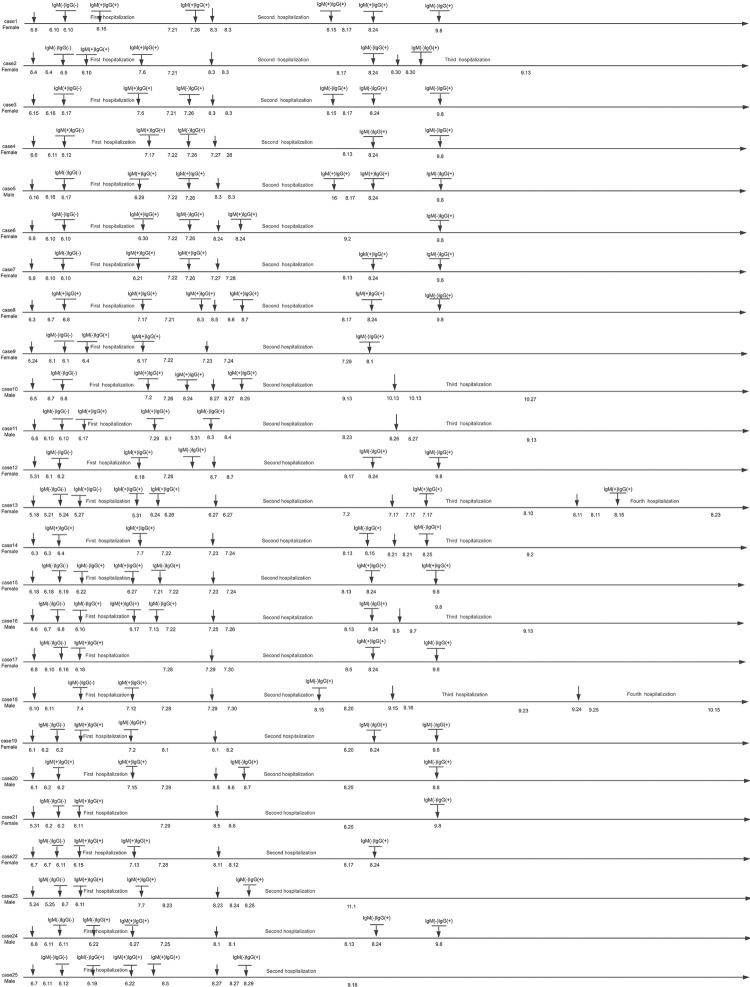

All patients with infection recurrence were asymptomatic and showed no abnormalities in the pulmonary computed tomography. They reported no contact with any other cases of infection recurrence or people with respiratory symptoms after their discharge. In addition, no infected family members were reported. The progression of cases from the onset, hospitalization, and the recurrent positive testing of 25 cases is shown in Figure 3. It should be noted that seven patients were positive for both, IgG and IgM antibodies at the time of their recurrent positive RT-PCR test.

Figure 3. The development of the process of recurrence from the onset of symptoms, through hospitalization and the recurrence of positive RT-PCR or serological tests in the 25 patients with infection recurrence.

Patient 13 was a unique case that warrants a special reporting. A 75-year-old woman, the first confirmed case in the latest outbreak in Guangzhou, was linked to all subsequent cases. She was hospitalized for 36 days until the discharge criteria were met. However, on the second day after discharge, she tested positive by RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2, and she was hospitalized again for further treatment for six days. Then, she was hospitalized again for 25 days due to a positive RT-PCR half a month later. Overall, she was hospitalized four times due to recurrence of positive RT-PCR results. The progression of the illness from the onset, during hospitalization, and the recurrent RT-PCR results of patients is shown in Figure 3.

Analysis of factors in patients with infection recurrence

In the recurrent group, only 4% of patients had been vaccinated before, while 31.6% of patients in the non-recurrent group had been previously vaccinated (χ2 = 7.902; P < .05). No significant factors regarding socio-demographic characteristics or initial clinical symptoms were observed between the two groups. Analysis of factors in patients with infection recurrence is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Analysis of patients with recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the follow-up.

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 123) | Non recurrent (n = 98) | Recurrent (n = 25) | χ2/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2.081 | 0.149 | |||

| Male | 50 (40.7) | 43 (43.9) | 7 (28.0) | ||

| Female | 73 (59.3) | 55 (56.1) | 18 (72.0) | ||

| Age (in years) | |||||

| <60 | 82 (66.7) | 67 (68.4) | 15 (60.0) | 0.628 | 0.428 |

| ≥60 | 41 (33.3) | 31 (31.6) | 10 (40.0) | ||

| Vaccination | |||||

| Yes | 32 (26.0) | 31 (31.6) | 1 (4.0) | 7.902 | 0.005 |

| No | 91 (74.0) | 67 (68.4) | 24 (96.0) | ||

| Diagnostic type | |||||

| Confirmed cases | 118 (95.9) | 93 (94.9) | 25 (100.0) | - | 0.582b |

| Asymptomatic infection | 5 (4.1) | 5 (5.1) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Yes | 50 (40.7) | 39 (39.8) | 11 (44.0) | 0.146 | 0.702 |

| No | 73 (59.3) | 59 (60.2) | 14 (56.0) | ||

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 14 (11.4) | 11 (11.2) | 3 (12.0) | 0.012 | 0.913 |

| No | 109 (88.6) | 87 (88.8) | 22 (88.0) | ||

| Fever | 0.030 | 0.863 | |||

| Yes | 56 (45.5) | 45 (45.9) | 11 (44.0) | ||

| No | 67 (54.5) | 53 (54.1) | 14 (56.0) | ||

| Cough | 0.964 | 0.326 | |||

| Yes | 55 (44.7) | 46 (46.9) | 9 (36.0) | ||

| No | 68 (55.3) | 52 (53.1) | 16 (64.0) | ||

| Dry throat | 2.396 | 0.122 | |||

| Yes | 34 (27.6) | 24 (24.5) | 10 (40.0) | ||

| No | 89 (72.4) | 74 (75.5) | 15 (60.0) | ||

| Sore throat | 0.012 | 0.913 | |||

| Yes | 14 (11.4) | 11 (11.2) | 3 (12.0) | ||

| No | 109 (88.6) | 87 (88.8) | 22 (88.0) | ||

| Expectoration | 0.391* | 0.532 | |||

| Yes | 13 (10.6) | 9 (9.2) | 4 (16.0) | ||

| No | 110 (89.4) | 89 (90.8) | 21 (84.0) | ||

| Length of hospital stay | 52.04±24.98 | 52.47±27.52 | 50.32±11.52 | 0.103 | 0.748 |

*Comparison of proportions were made by the Fisher’s exact test.

Assessment of symptoms during the follow-up

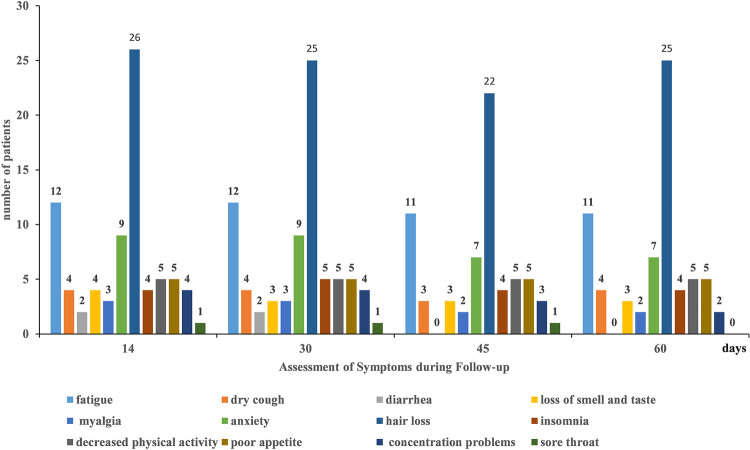

A total of 109 patients answered the symptoms questionnaires during the follow-up period (Figure 4). The most common symptom after discharge was hair loss, followed by fatigue. Two months after discharge, 59.6% of patients reported having no long-term COVID-19 symptoms at all.

Figure 4. Assessment of symptoms related to COVID-19 during follow-up visits. Ob the X-axis, the discharge time in days, and on the Y-axis, the absolute number of patients reporting each of the COVID-19- related symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, with its increasing transmissibility and capability to cause more serious infections, was the main reason for severity of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in India. At present, the Delta variant is predominant among all variants and is the most commonly reported variant around the world 9 . It is believed to be the most transmissible variant, which is more easily propagated than the Alpha variant firstly found in the United Kingdom 10 . However, there are few studies on the follow-up of discharged patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2. The recurrence rate and potential propagation risk of the Delta variant, which was associated with higher infectivity and virulence, remain unclear. To our knowledge, this is the first follow-up of discharged patients with Delta variant infections in China.

Our follow-up showed that 20.33% of included patients showed recurrent positive results for SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR after discharge. We found that eight patients tested positive for infection through RT-PCR on the first day after discharge. On the premise of standardized sampling operation, it is speculated that false-negative nucleic acid tests at discharge may be one of the reasons for this result. Angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) receptors, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter host cells, were found to be more highly expressed in the lungs than the upper respiratory tract 11 . There is sufficient evidence to support that the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs is higher than that in the upper respiratory tract, which leads to a negative test result in that the virus cannot be detected by a nasopharynx swab sampling. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to comprehensively judge whether the patient’s viral infection status changes from positive to negative in combination with the test results of a variety of other samples, such as sputum and blood.

Theoretically, patients with infection recurrence are potential transmission sources. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports of human infection cases resulting from the contact with a recurrently positive patient. Previously, it was found in South Korea that the viral particles detected in a discharged patient were dead remnants 12 . In addition, no confirmed cases were reported among close contacts. These findings support that a recurrent positive test for SARS-CoV-2 is likely to detect inactivated viral RNA rather than re-activation or re-infection. Infectivity depends upon the viral replication 13 . We found that there was a certain proportion of individuals actively infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 returning to the community after discharge from the hospital. However, there were no clinical symptoms or deterioration in pulmonary computed tomography findings in all cases. The vast majority of cycle threshold results by RT-PCR assay were greater than 33, suggesting that patients with infection recurrence have a low risk of community transmission.

Previously, our research team conducted a test-negative case–control study to explore the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in the real world. It was found that, although a single dose of vaccine did not provide sufficient protection, two doses of a vaccine containing inactivated viruses remained effective against the Delta variant infection, with an estimated potency exceeding the World Health Organization minimum threshold of 50% 14 . In this study, only 4% of patients in the recurrent group had been vaccinated before, compared to 31.6% of patients in the non-recurrent group. This may be related to the establishment of a stronger humoral immune response in vaccinated people.

In addition, the symptoms most likely to persist until two months in our cohort were hair loss, fatigue anxiety problems, and 40.4% of patients reported long-term COVID-19 symptoms, suggesting a significant reduction in both, the physical and the mental quality of life of discharged patients. The duration of these symptoms remains to be studied in the future.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, it included only a small number of discharged patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, the follow-up studies involving larger cohorts need to be conducted. Secondly, in the future, we should strive to isolate samples of live virus instead of performing RT-PCR assays to determine the true infectivity of patients for the purpose of continuous disease management after discharge.

CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that it is possible for patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 to show recurrent positive results for SARS-CoV-2 infection after discharge, indicating that mass vaccination against the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 to be an appropriate goal. Both, the physical and the mental quality of life of discharged patients were significantly affected, but the duration of observed symptoms remains to be further observed in the future. This study has specific significance for driving necessary improvements in the post-discharge management of patients infected with the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work was supported by the Key Project of the Medicine Discipline of Guangzhou (Nº 2021-2023-11); the Medical Health Technology Project for Guangzhou (Nº 20201A011062); the Medical Science and Technology Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nº A2021372) and the Foshan Scientific and Technological Key Project for COVID-19 (Nº 2020001000430).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lu HI, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kordzadeh-Kermani E, Khalili H, Karimzadeh I. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and complications of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Future Microbiol. 2020;15:1287–1305. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2020-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui DS, Azhar EI, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health: the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xin X, Li SF, Cheng L, Liu CY, Xin YJ, Huang HL, et al. Government intervention measures effectively control COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:77–83. doi: 10.1007/s11596-021-2321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazafa A, Ur-Rahman K, Jahan N, Mumtaz M, Farman M, Naeem N, et al. The broad-spectrum antiviral recommendations for drug discovery against COVID-19. Drug Metab Rev. 2020;52:408–424. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2020.1770782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv Z, Cheng SH, Le J, Huang JT, Feng L, Zhang BH, et al. Clinical characteristics and co-infections of 354 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian R, Wu W, Wang CY, Pang HY, Zhang ZY, Xu HP, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival analysis in critical and non-critical patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a single-center retrospective case control study. 17524Sci Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74465-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dao TL, Hoang VT, Gautret P. Recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;40:13–25. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-04088-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torjesen I. Covid-19: Delta variant is now UK’s most dominant strain and spreading through schools. n1445BMJ. 2021;373 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandar S, Ravisankar M, Kumar RS, Jakkan K. A comprehensive review on Covid-19 Delta variant. Int J Pharmacol Clin Res. 2021;5:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang YJ. South Korea’s COVID-19 infection status: from the perspective of re-positive test results after viral clearance evidenced by negative test results. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14:762–764. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li XN, Huang Y, Wang W, Jing QL, Zhang CH, Qin PZ, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant infection in Guangzhou: a test-negative case-control real-world study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10:1751–1759. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1969291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]