Abstract

Purpose of Review

Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound (CeTRUS) is an emerging imaging technique in prostate cancer (PCa) diagnosis and treatment. We review the utility and implications of CeTRUS in PCa focal therapy (FT).

Recent Findings

CeTRUS utilizes intravenous injection of ultrasound-enhancing agents followed by high-resolution ultrasound to evaluate tissue microvasculature and differentiate between benign tissue and PCa, with the latter demonstrating increased enhancement. The potential utility of CeTRUS in FT for PCa extends to pre-, intra- and post-operative settings. CeTRUS may detect PCa, facilitate targeted biopsy and aid surgical planning prior to FT. During FT, the treated area can be visualized as a well-demarcated non-enhancing zone and continuous real-time assessment allows immediate re-treatment if necessary. Following FT, the changes on CeTRUS are immediate and consistent, thus facilitating repeat imaging for comparison during follow-up. Areas suspicious for recurrence may be detected and target-biopsied. Enhancement can be quantified using time-intensity curves allowing objective assessment and comparison.

Summary

Based on encouraging early outcomes, CeTRUS may become an alternative imaging modality in prostate cancer FT. Further study with larger cohorts and longer follow-up are needed.

Keywords: Contrast-enhanced, Ultrasound-enhancing agents, Focal therapy, HIFU, Microbubbles, Prostate cancer

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is an increasingly utilized diagnostic imaging modality. CEUS relies on intravenous injection of ultrasound-enhancing agents (UEAs), followed by high-resolution imaging of tissue blood flow utilizing standard ultrasound units (GE, Philips, Toshiba, Hitachi) and commercially available proprietary software. The term UEA was recently published by the American Society of Echocardiography to distinguish it from iodinated or gadolinium-based contrast agents [1].

The primary diagnostic features of CEUS rely on an evaluation of the microvascular architecture and contrast-enhancement of a region of interest or lesion compared to adjacent normal tissue [2•]. Real-time wash-in and wash-out phases of the UEA allow differences between tissues to be evaluated both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound (CeTRUS) has several potential roles in the management of prostate cancer (PCa) including diagnosis, facilitating targeted prostate biopsy, real-time evaluation and confirmation of adequate tissue ablation after focal therapy, and identification of post-treatment recurrence during post-ablation surveillance.

Ultrasound-Enhancing Agents

The majority of current UEAs use microspheres of inert gas covered with a lipid or polymer shell. Encapsulated microbubbles characteristically are small enough to pass through the pulmonary circulation and enter the systemic circulation, yet large enough to not escape the endothelium and therefore act as purely intra-vascular contrast agents [3]. The microspheres are smaller than red blood cells, but larger than the iodine and gadolinium particles used for contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), respectively. The gas typically is a high-molecular weight, high-density gas with low solubility, while the shell provides strength and stability; the combination provides the compound with durability, consistency, and clinical utility. After circulating for several minutes, the microspheres dissolve, the internal gas is exhaled, and the coating, which may be protein, lipid, or polymer, is metabolized, primarily by the liver [4].

The current commercially available UEAs with regard to commercial name, manufacturer, mean size, outer shell, and gas constituent are as follows, respectively [1]:

Optison (perflutren protein type-A microspheres); GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK; 3.0–4.5 μm; Human albumin; perflutren.

SonoVue or Lumason (sulfur hexafluoride lipid-type A microspheres); Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy; 1.5–2.5 μm; phospholipid; sulfur hexafluoride.

Definity or Luminity (perflutren lipid microsphere); Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA, USA; 1.1–3.3 μm; phospholipid; perflutren.

Safety of UEAs

There have been numerous studies confirming the safety and efficacy of UEAs in clinical practice including in cardiology, emergency department, pediatrics, critical care settings among others, with a very low incidence of adverse events [1, 2•]. There are no nephro-, hepato-, or cardio-toxic side effects and there is no requirement for pre-procedural laboratory assessments. A multiinstitutional study of 5576 patients undergoing contrast-enhanced echocardiography over a 5-year period reported an adverse event rate of 0.27%, with all adverse events being mild and transient, and all patients making complete recovery [5]. A retrospective analysis of 78,383 studies over 6.5 years including over 10,000 studies in critically ill patients demonstrated a severe adverse event in 8 patients (0.01%) including 4 patients with suspected anaphylactoid reaction (0.006%) [6]. Nevertheless, CEUS should be performed in facilities with appropriate expertise to manage these rare adverse events [2•]. Most UEAs are contraindicated in patients with known or suspected right-to-left or bidirectional cardiac shunts although the restriction has been lifted for Lumason [7]. The other major contraindication is known hypersensitivities, while Optison is also contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to blood products or albumin [8]. UEAs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for evaluation of left ventricular obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux in pediatric patients and Lumason has recently been approved for evaluation of the liver in adult and pediatric patients [9, 10].

Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Other Organ Systems

Although our emphasis is on PCa in this review, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has shown promising efficacy in the diagnosis or post-treatment evaluation of tumors in several other organ systems including brain [11], breast [12], liver [13], soft tissue sarcoma [19], ocular melanoma [14], pancreas [15], lymphoma [16], kidney [16], and bladder [17]. Specifically, CEUS demonstrates improved characterization of focal liver lesions [18], and is currently recommended as a safe and cost-effective second-line diagnostic imaging modality in this setting [19]. A recent meta-analysis showed satisfactory pooled sensitivity and specificity of CEUS in distinguishing pancreatic cancer from benign pancreatic lesions [15]. In bladder cancer, CEUS may have utility in distinguishing low-grade and high-grade bladder urothelial carcinoma with potential implications for diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment [17].

CEUS has utility in guidance and follow-up after ablative procedures for hepatic and renal masses [13, 20]. Immediate post-procedure CEUS is able to assess the ablation zone and identify residual tumor in primary or metastatic liver lesions treated with radiofrequency ablation [13]. Further, post-ablation CEUS may be a reliable alternative to contrast-enhanced MRI for monitoring therapeutic response to hepatic ablation [21]. CEUS has been shown to accurately assess the therapeutic efficacy of percutaneous high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for uterine fibroids [13, 22, 23] as well as microwave ablation for benign breast lesions [24]. CEUS has been shown to be a safe and effective imaging modality in guiding ablative treatment [26] and assessing the therapeutic response to microwave and radiofrequency ablation of renal tumors [25-27]. Initially detailed in 2005, early experience with CEUS following cryoablation of small renal masses suggests up to 100% sensitivity and 90–100% specificity, comparable to contrast-enhanced CT imaging but without the associated renal toxicity or radiation [28, 29].

Histological Changes with Ablation Therapies for Prostate Cancer: The Rationale for CEUS

The majority of current ablation therapies for PCa ultimately lead to tissue coagulative necrosis by decreasing or impairing blood supply [30]. In HIFU, the targeted tissue at the focal point absorbs the high intensity acoustic energy and converts it into heat. The thermal effect of a rise in temperature above the coagulation threshold (> 60 °C) results in almost immediate sharply demarcated coagulative necrosis with cell death within the target area of the prostate [31]. In fact, the tissue damage after HIFU also occurs due to the mechanical effect of the generation of gas bubbles, and collapse of cavities with subsequent rupture of cell walls. These processes lead to immediate coagulative necrosis, followed by an inflammatory response and induction of fibrosis. The irreversible nature of the tissue ablation has been confirmed by ultrastructural analysis using electron microscopy. Madersbacher et al. evaluated the histological impact of HIFU on in vivo PCa in a cohort of 29 patients treated with HIFU followed by immediate radical prostatectomy under the same general anesthetic [32]. A zone of sharply delineated intra-prostatic coagulative necrosis was observed in all specimens. De la Rosette et al. published a series of 9 patients treated with HIFU focal therapy followed by radical prostatectomy after 7–12 days, demonstrating a spectrum of morphological changes ranging from apparent light microscopic necrosis to more subtle ultrastructural cell damage [33, 34]. Further, HIFU may be able to induce small vessel occlusion and thrombosis, which can further contribute to infarction and necrosis of the perfused tissue [35]. A similar mechanism of thermal coagulative necrosis has been demonstrated with transperineal radiofrequency ablation of prostatic tissue where central temperatures can reach up to 105 °C during treatment [36].

In cryoablation, the tissue temperature is reduced below the cytotoxic freezing threshold under ultrasound guidance to ablate tissue [37, 38]. One or multiple freeze-thaw cycles are performed, resulting in protein denaturation, direct rupture of cell membrane by crystal formation, and vascular stasis and secondary microthrombi formation resulting in ischemic cell death and coagulative necrosis [39, 40]. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) uses a high-voltage, low-energy current between transperineally placed electrodes. The electric current creates permanent nanopores in the cell membrane resulting in cell death from apoptosis and non-thermal tissue ablation [41].

Contrast-Enhanced Transrectal Ultrasound: Evaluation of Prostate Cancer and Ablation Therapy

Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound (CeTRUS) can be performed for several different purposes including, PCa diagnosis, pre-operatively for surgical planning, intra-operatively for real-time evaluation of the ablation zone, and on follow-up for surveillance after ablative therapies. These can be assessed by both qualitative information and quantitative data.

CeTRUS: Technique

The CeTRUS examinations are performed on commercially available ultrasound units, with a high-frequency endorectal probe. Grayscale, color Doppler, and power Doppler imaging are initially performed to assess the prostate volume and any target lesions including size, morphologic characteristics, echogenicity, and Doppler signal. The patients are informed of the off-label use of UEAs and their potential side-effects.

For CeTRUS, a dual-scan mode is used to allow simultaneous visualization of CeTRUS and B-mode images. A 2.5 mL bolus of Lumason™ is injected intravenously followed by a 10 mL normal saline flush, with an option to re-bolus as required. Post contrast cine images of the region of interest are obtained using low mechanical index settings and Contrast Pulsed Sequence techniques. The inflow of UEA in a single axial plane is imaged initially and can be performed to image several planes with multiple UEA injections if required. Images are acquired for a 2-min video clip and are stored for time-intensity curve (TIC) evaluations, suspicious lesion characterization, surgical planning, and follow-up surveillance.

CeTRUS in Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

CeTRUS has potential roles in real-time diagnosis of PCa and facilitating targeted prostate biopsies [42]. Prostate cancer exhibits an altered microvascular environment with neoangiogenesis and increased microvessel density within the prostatic tissue which forms the basis for CeTRUS imaging in detecting PCa [43-45].

The first ultrasound technique to detect vascularity within the prostate was Doppler imaging which measures relative blood flow [46]. While prostate Doppler imaging is able to assess perfusion, it relies on blood flow in larger macrovessels (100 μm) and thus it may be inadequate for detecting the low flow velocities within the microvasculature of PCa. On the contrary, CeTRUS is able to assess perfusion within the small microvessels (40 μm) seen in PCa [47-50]. Prostate cancer tissue with increased microvessel density manifests as increased enhancement on CeTRUS compared to the normal benign prostate tissue [51].

CeTRUS has been utilized for detection of PCa with encouraging performance characteristics including a positive predictive value up to 91.7%, sensitivity up to 79.3%, and accuracy of 83.7% [52-55]. Further, the addition of CeTRUS-guided targeted prostate biopsy of areas of hyperenhancement may be associated with significantly improved cancer detection rate compared to 12-core systematic biopsy [54, 56].

CeTRUS Semi-Quantitative Analysis: Defining Enhancement Patterns

Rouviere et al. studied the use of CeTRUS in patients undergoing whole prostate gland HIFU ablation. They correlated imaging findings on CeTRUS and MRI with prostate biopsy at 30–45 days [57•]. The study prospectively enrolled 28 consecutive patients: 19 had primary treatment for localized PCa, while 9 had salvage HIFU for local radiation-recurrent PCa. Patients underwent gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI 1–3 days after HIFU ablation. CeTRUS with sulfur hexafluoride UEA was performed before HIFU treatment, 1–3 days and 30–45 days after treatment. Additionally, six patients underwent a CeTRUS 15–30 min after treatment. CeTRUS-guided biopsies were taken on days 30–45 of both non-enhancing areas and enhancing areas of the prostate. Both CeTRUS and MRI images were reviewed by experienced uro-radiologists blinded to the pre- and post-treatment prostate biopsies. The authors proposed a semi-quantitative, subjective scale of enhancement for each prostate lobe as follows: S0, no enhancement; S1, mild and/or patchy enhancement but no marked enhancement; S2, marked enhancement in at least one part of the prostate. The enhancement patterns were compared with histopathology.

A devascularized ablation zone was seen within 15–30 min of treatment. CeTRUS at 1–3 and 30–45 days demonstrated the devascularized prostate as a non-enhancing zone with peripheral enhancement in all patients. These findings were concordant with contrast-enhanced MRI. Non-enhancing areas correlated with non-viable tissue on biopsy while foci of residual enhancement within the ablated prostate were associated with a significant probability of harboring viable tissue. CeTRUS findings were stable from day 1 to day 45 post-treatment and correlated well with MRI and biopsy findings. Assessing a total of 248 biopsy samples, the viable tissue rate correlated to the semi-quantitative enhancement patterns, as follows: 6.2% for S0 sites, 34% for S1 sites, and 60% for S2 sites. The authors concluded that CeTRUS is a promising imaging modality for distinguishing between ablated (non-enhancing) and viable (enhancing) tissue.

The study evaluated CeTRUS after whole-gland HIFU ablation only and had a short follow-up period of 1.5 months. Further, the authors did not differentiate between viable benign tissue and viable malignant tissue in the statistical analysis.

CeTRUS Quantitative Analysis: The Time-Intensity Curves

Quantitative analysis offers a standardized and objective method for prostate ablation evaluation. Proprietary software compatible for available ultrasound machines are used to post process raw data of CeTRUS. The processing consists of the following steps: (1) creation of regions of interest (ROIs) within the suspected tumor or ablated prostate, as well as in contralateral normal tissue (internal control); (2) correction for “in-plane” motion; (3) extraction of the echo mean for each ROI to create a timeline; and (4) curve fitting the echo mean timeline to the local density random walk wash-in/wash-out equation to calculated values. The resulting timeline, or time-intensity curve (TIC) plots echo mean (in dB, on the Y-axis) against time (on the X-axis). Quantitative parameters including peak intensity (PI), wash-in slope (WIS), and time-to-peak (TTP) and area under the curve can be derived from the TIC.

Interpretation relies on comparison of the ROI (or treated prostate tissue) with contralateral tissue. Prostate cancer has been shown to exhibit higher PI, a steeper WIS, and earlier TTP compared with normal (benign) tissue [58, 59]. Ablated prostate tissue is expected to demonstrate a “flat” curve, with minimal slope compared with untreated tissue [60•].

CeTRUS in Prostate Ablation Therapies: Animal Models

Pre-clinical studies demonstrated that CeTRUS can be used to guide and monitor radiofrequency and microwave ablation of the prostate in the canine models [61-63]. Liu et al. reported the use of continuous CeTRUS for the assessment of whole-gland radiofrequency ablation in nine dogs [61]. On step-sectioned prostatectomy specimen, the ablated lesion volume was proportional to the ablation time and power settings, with good correlation between ultrasound and histopathological volumes. Cheng et al. compared the value of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) MRI, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, and CeTRUS performed immediately after prostate microwave therapy in seven dogs [63]. The MRI and ultrasound imaging were correlated with histological changes on prostatectomy specimens. Both CeTRUS and DCE MRI were able to demonstrate 8 of the 11 lesions identified on histology as a non-enhancing core surrounded by an enhancing rim peripherally reflecting a central area of vascular damage. The areas of non-enhancement were highly correlated between ultrasound and MRI (r = 0.997, p < 0.001).

Intra-Operative Monitoring and Follow-Up Evaluation in Prostate Cancer Focal Therapy

Intra-procedural monitoring of ablative procedures is important with regard to monitoring the extent of tissue ablation. Underestimation of the ablation zone may lead to overtreatment and injury to vital structures compromising potency, continence, and voiding function while overestimation of the treatment area may lead to incomplete ablation and oncologically inferior outcomes with increased risk of local and systemic progression. Reliable techniques for intra-operative radiological monitoring during focal therapy are lacking. For example, many ablative therapies cannot be visualized on regular grayscale ultrasound. Furthermore, shift and swelling of the prostate may lead to mismatch of planned and actually ablated areas leading to undertreatment [64]. Therefore, real-time monitoring of the ablated area is crucial. While multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) is currently recognized as the optimal imaging modality for follow-up, it plays no role in real-time intra-operative guidance and may have limited utility during the early follow-up period. CeTRUS may provide a practical, cost-effective, reproducible tool that can reliably monitor and assess the therapeutic effect of the ablative procedure both intra-operatively and post-operatively, particularly in patients or procedures where MRI is not feasible or is contraindicated.

While close surveillance after focal therapy is essential, there are no standardized guidelines on the optimal strategy for follow-up. Most surveillance schedules involve a combination of periodic prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements, digital rectal examination, imaging, and prostate biopsy. A Delphi consensus project [65] suggested that mpMRI and prostate biopsy should be performed at 6 and 12 months, and a 1 year, respectively. PSA changes are an unreliable measure of treatment effect as PSA is not PCa-specific and can vary depending on the baseline prostate size and the volume of prostate ablated. PSA is also altered by infection or inflammation. Further, there is no standardized definition of biochemical failure after focal therapy.

Advantages of CeTRUS in Follow-up After Focal Therapy for Prostate Cancer

Hypervascularity is one of the hallmarks of PCa recurrence [66]. As such, DCE MRI is one of the most important parameters of mpMRI during surveillance as it may identify PCa recurrence after ablation by early focal enhancement [65, 67, 68]. In fact, among the various MRI sequences, DCE-MRI may be the most sensitive (80–87%) for the identifying recurrence after HIFU ablation of PCa with an accuracy of 71–73% [69]. Similarly, CeTRUS is able to demonstrate enhancement in cancerous tissue following intravenous injection of UEA. CeTRUS demonstrates contrast uptake in even the smallest intra-tumoral vessels, commonly seen in PCa due to neovascularization [47]. Devascularization following ablation manifests as lack of contrast uptake on CeTRUS [70], which has been shown to correlate with non-viable tissue on biopsy, while areas of enhancement in ablated prostate have a high probability of harboring viable tissue [57•].

CeTRUS has several advantages over MRI as a technique to guide and evaluate efficacy following focal ablation of PCa (Table 1) [50]. CeTRUS allows continuous dynamic real-time imaging after UEA injection as opposed to the intermittent static acquisitions of MRI which means CeTRUS may be able to identify (early or late) enhancement not seen during the specific pre-determined timing of DCE MRI. Further, real-time imaging allows intra-procedural interpretation of findings while the ability to give multiple UEA boluses facilitates repeat assessment of enhancement during the same CeTRUS study. In addition to qualitative information, CeTRUS can facilitate semi-quantitative and quantitative analysis. Further, CeTRUS allows for high temporal resolution imaging with thin slice thickness. Compared to CeTRUS, MRI is expensive, time-consuming, requires an experienced radiologist for interpretation, is not amenable to being repeated within minutes, and has a number of well-recognized relative contraindications [71].

Table 1.

Comparison of CeTRUS and mpMRI for evaluation of focal ablation therapies of the prostate

| Parameter | CeTRUS | mpMRI |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Yes | Maybe |

| Real-time | Yes | No |

| Non-invasive | Yes | Yes |

| Low cost | Yes | No |

| Low side effects | Yes | Yes |

| Use in patients with impaired renal function | Yes | Maybe# |

| No radiation | Yes | Yes |

| Office-based procedure | Yes | No |

| Time to complete | Short | Long |

| Expertise required | TRUS | Specialized radiologist |

| Relative contraindications | ||

| Metal Prosthesis | No | Yes |

| Hip replacement | No | Yes* |

| Pacemaker | No | Maybe$ |

| Claustrophobia | No | Maybe^ |

| US FDA-approved | Off label | Yes |

TRUS transrectal ultrasound, CeTRUS contrast-enhanced TRUS, mpMRI multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, US FDA United States Food and Drug Administration

Exclusion of patients with impaired renal function is institution-dependent depending on type of MRI contrast agent used

Creates imaging artifact that may preclude imaging interpretation

Some pacemakers may be compatible with MRI imaging with manufacturer and cardiology support

Anxiolytics and/or sedation may be used to overcome claustrophobia in selected patients

Importantly, CeTRUS demonstrates an ablation zone immediately after focal ablation and these imaging findings are stable during follow-up apart from treatment-related atrophy in the ablated lobe [57•]. The findings on MRI, however, are dynamic and change significantly during the course of follow-up [72]. Immediately following HIFU ablation, the treated lobe appears as a central devascularized non-enhancing zone (due to coagulative necrosis) surrounded by a rim of enhancement on DCE MRI (due to inflammation and edema) [69, 72]. During this time, it may be difficult to diagnose residual/recurrent PCa both due to the small size of the lesions and an inability to distinguish cancer from an inflammatory rim of enhancement [73]. In the ensuing months after HIFU ablation, the peripheral rim of enhancement disappears as coagulation necrosis is replaced progressively by fibrosis [73]. CeTRUS findings following ablative therapies, on the other hand, are immediate and stable during follow-up with good correlation between “in-field” enhancement on CeTRUS and residual viable, and potentially cancerous, prostate tissue [57•]. Thus, in the early post-operative period, CeTRUS may be able to identify residual disease while MRI findings are still evolving [66, 74]. We hypothesize that the inflammatory rim enhancement seen on MRI may be due to interstitial enhancement from gadolinium molecules extravasating into the extravascular space whereas CeTRUS provides strictly intra-vascular enhancement and may be less impacted by post-treatment inflammatory processes.

CeTRUS in Focal HIFU for Prostate Cancer

CeTRUS is particularly useful in HIFU focal ablation where the lack of contrast enhancement helps define and delineate the sharply demarcated borders of coagulative necrosis. De la Rosette and colleagues demonstrated that the absence of enhancement on CeTRUS corresponded with the area of HIFU ablation [70, 75]. Nine patients received HIFU hemi-gland ablative therapy followed by radical prostatectomy a week later. CeTRUS was performed the day before prostatectomy [70]. The HIFU-treated areas were characterized by absence of blood flow, and the CeTRUS-measured HIFU volume correlated well with the histological HIFU volume. Apfelbeck et al. evaluated short-term findings on CeTRUS in 12 patients undergoing focal HIFU ablative therapy [76]. CeTRUS was performed 1 day prior to HIFU, immediately after HIFU, and 24 h later. Persistent perfusion was seen in the capsule in all patients and in the anterior prostate for large prostate glands. In this study, two patients were retreated due to persistent microbubble enhancement in the anterior prostate immediately following the first HIFU treatment. Both patients demonstrated adequate ablation of the treated lobe after retreatment. While the study population was mainly D'Amico low-risk and heterogeneous in extent of treatment received, the authors demonstrated lack of enhancement immediately and 24 h after treatment indicating that the thermal vascular and perfusion changes can be seen on CeTRUS immediately post-HIFU.

In a recent proof-of-concept study with patients undergoing hemi-gland HIFU ablation of the prostate and pre-operative, intra-operative and follow-up CeTRUS studies, our impressions are as follows [60•] (Fig. 1):

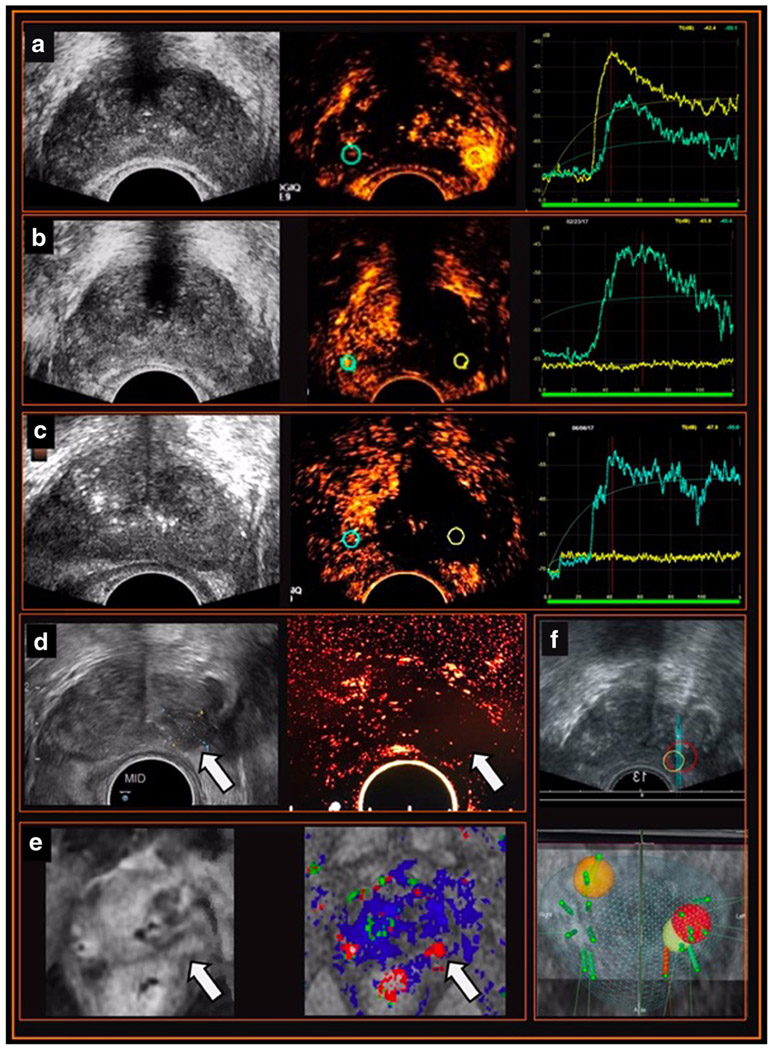

Fig. 1.

Example of the utility of CeTRUS in HIFU ablation focal therapy for prostate cancer in the pre-operative, intra-operative, and surveillance settings. A 79-year-old man with a focal left mid to apex PIRADS 4 lesion on MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and biopsy-proven recurrent Gleason 3 + 4 prostate cancer elected for left hemi-gland salvage HIFU (high-intensity focused ultrasound) ablation of the prostate. a Pre-HIFU CeTRUS (contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound). Grayscale ultrasound shows no echogenic lesion. Qualitative assessment of the static image during contrast injection shows early avid enhancement at left mid to apex corresponding to the dominant lesion on MRI. Time-intensity curves (TIC) demonstrate higher peak intensity (PI), steeper wash-in slope (WIS), and earlier time-to-peak (TTP) within the cancer-harboring left lobe (yellow) compared with the normal right lobe (blue). b Immediate post-HIFU CeTRUS. Grayscale ultrasound shows no significant changes in the ablated left lobe. Qualitatively, CeTRUS demonstrates no enhancement in the treated left lobe (yellow) suggesting adequate hemi-ablation compared to normal enhancement in the untreated right lobe (blue). Quantitatively, the TIC (right) shows a flat yellow waveform in the ablated zone (yellow) and a normally enhancing waveform in the untreated lobe (blue). c Surveillance CeTRUS at 3 months follow-up. Grayscale ultrasound is non-contributory. CeTRUS demonstrates persistent lack of enhancement in treated left lobe (yellow) similar to the immediate post-treatment study, and normal enhancement in the untreated right lobe (blue). TIC shows a persistent flat waveform in the ablated left lobe (yellow). d Surveillance CeTRUS at 12-month follow-up. Grayscale ultrasound shows a hypoechoic lesion in the previously treated left lobe (arrow). CeTRUS continues to demonstrate no enhancement in the ablated left lobe (arrow). e mpMRI at 12 months. The T1 contrast-enhanced (left) and DCE imaging (right) show an area of suspicious enhancement in the previously treated mid to apical left lobe (arrow). f Prostate biopsy at 12 months. MRI targeted biopsy of the suspicious area (yellow and red targets) shows no evidence of cancer. However, a targeted biopsy of a de novo area of increased enhancement on MRI and CeTRUS (orange target) showed recurrent prostate cancer in the contralateral (right) base

Live feedback of treatment effect facilitates close monitoring of the ablation zone.

Immediate post-treatment CeTRUS clearly demonstrated the HIFU ablation defect as a sharply demarcated non-enhancing zone compared to a normally enhancing contralateral lobe.

CeTRUS demonstrated adequate tissue ablation at 6 and 12 months as a persistent non-enhancing zone and this correlated with MRI and biopsy histology.

CeTRUS was able to identify suspicious foci of recurrent cancer within the ablation zone as a hyper-enhancing zone, facilitating image-guided prostate biopsy which confirmed the diagnosis of recurrent PCa.

CeTRUS findings correlated with mpMRI and biopsy histology.

CeTRUS in Other Focal Therapies for Prostate Cancer

Though clinical studies are limited mostly to proof-of-concept manuscripts, CeTRUS has been used in brachytherapy [77] and focal IRE [78•, 79•, 80]. Pieters et al. investigated the potential utility of CeTRUS in localization of intra-prostatic lesions to facilitate treatment planning in 8 patients receiving pulsed-dose rate brachytherapy boost in addition to external beam radiotherapy [77]. They found that dose coverage of intra-prostatic lesions may be optimized with CeTRUS without any associated increase in radiation dose to adjacent at-risk organs.

CeTRUS has been used to assess the therapeutic effect of focal IRE [78•, 79•, 80]. In one study, 13 patients with histologically proven PCa were treated with focal IRE and assessed by CeTRUS before, immediately post-treatment, and 1 day after treatment [80]. The authors proposed a 5-point Likert scale to convert the qualitative assessment of enhancement of the lesion or the ablation zone on contrast-enhanced images into a semi-quantitative grading system, as follows: 5, pronounced hypervascularization; 4, clear vascularization; 3, moderate vascularization comparable to the surrounding tissue; 2, low vascularization; 1, only partial vascularization and low in comparison with surrounding tissue; and 0 was no enhancement. CeTRUS demonstrated immediate and marked reduction in enhancement after IRE-ablation with the grade (according to the above system) reducing from 2.15 pre-operatively to 0.65 post-operatively (p < 0.001). Within 24 h, the enhancement further reduced from 0.65 to 0.27 (p = 0.028). This study, however, did not correlate CeTRUS findings with histopathology. The same group then reported a retrospective analysis of 25 patients undergoing focal IRE with mid-term follow-up [78•]. CeTRUS was completed at 1 day, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after focal IRE and showed a persistent ablation zone during the course of 6 months. There was significant involution in the prostate volume in the first 3 months after ablation, while the ablation zone continued to decrease during the first 6 months. This study was also limited by its retrospective design and lack of histological correlation. A prospective phase I-II study assessing TRUS, CeTRUS, and mpMRI in 16 patients undergoing focal IRE prior to scheduled radical prostatectomy found that while grayscale TRUS was inadequate in assessing IRE, 11 of 12 patients with post-IRE CeTRUS at 4 weeks showed a distinct homogenous non-enhancing ablation zone in the treated area [79•]. CeTRUS and mpMRI were comparable for assessing the therapeutic effect of IRE with good correlation with histopathology (r =0.80 and 0.88, respectively).

Conclusions

In summary, CeTRUS is a cost-effective imaging modality in the guidance, immediate post-treatment assessment and follow-up of ablative focal therapies in prostate cancer. CeTRUS is able to identify neovascularization within the primary or recurrent prostate cancer tissue which manifests as increased uptake of contrast compared to benign prostatic tissue. Distinguishing different patterns of enhancement facilitates semi-quantitative assessment, while the time-intensity curves provide quantification of the enhancement thereby reducing the subjectivity of assessment. During focal therapy, CeTRUS is able to provide real-time visualization of the ablation zone with clear and sharp margins and give live feedback facilitating immediate re-treatment if necessary. The treated area can be visualized immediately following ablation and these radiological findings are consistent on repeat imaging, therefore facilitating ongoing follow-up and comparison. Further, early data suggests that CeTRUS may be able to identify post-treatment recurrence facilitating targeted biopsies and guiding salvage treatment if required. Studies with larger cohorts, longer term follow-up and correlation with MRI and biopsy findings are needed to establish the role of CeTRUS in focal therapy. Based on encouraging early results, CeTRUS could become an alternative test for the radiological monitoring of focal ablative treatments in the near future.

Abbreviations

- CEUS

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- CeTRUS

Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound

- DCE

Dynamic contrast-enhancement

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- HIFU

High-intensity focused ultrasound

- IRE

Irreversible electroporation

- mpMRI

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- PI

Peak intensity

- PSA

Prostate-specific antigen

- ROI

Region of interest

- TIC

Time-intensity curve

- TTP

Time-to-peak

- UEA

Ultrasound-enhancing agents

- US FDA

United States Food and Drug Administration

- WIS

Wash-in slope

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Akbar N. Ashrafi, Nima Nassiri, Inderbir S. Gill, Mittul Gulati, Daniel Park, and Andre L. de Castro Abreu each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Porter TR, Mulvagh SL, Abdelmoneim SS, Becher H, Belcik JT, Bierig M, et al. Clinical applications of ultrasonic enhancing agents in echocardiography: 2018 American Society of Echocardiography guidelines update. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(3):241–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.•. Dietrich CF, Averkiou M, Nielsen MB, et al. How to perform contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Ultrasound Int Open. 2018;4(1):E2–E15. This manuscript provides a great review of ultrasound enhancing agents, how to perform contrast-enhanced ultrasound, and the technical parameters to optimize CEUS performance.

- 3.Brannigan M, Burns PN, Wilson SR. Blood flow patterns in focal liver lesions at microbubble-enhanced US. Radiographics. 2004;24(4):921–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correas JM, Meuter AR, Singlas E, Kessler DR, Worah D, Quay SC. Human pharmacokinetics of a perfluorocarbon ultrasound contrast agent evaluated with gas chromatography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27(4):565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platts DG, Luis SA, Roper D, Burstow D, Call T, Forshaw A, et al. The safety profile of perflutren microsphere contrast echocardiography during rest and stress imaging: results from an Australian multicentre cohort. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22(12):996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei K, Main ML, Lang RM, Klein A, Angeli S, Panetta C, et al. The effect of Definity on systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25(5):584–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker JM, Weller MW, Feinstein LM, Adams RJ, Main ML, Grayburn PA, et al. Safety of ultrasound contrast agents in patients with known or suspected cardiac shunts. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(7):1039–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appis AW, Tracy MJ, Feinstein SB. Update on the safety and efficacy of commercial ultrasound contrast agents in cardiac applications. Echo Res Pract. 2015;2(2):R55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seitz K, Strobel D. A milestone: approval of CEUS for diagnostic liver imaging in adults and children in the USA. Ultraschall Med. 2016;37(3):229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern DF, Eliot L, Bigler RS, Fabes RA, Hanish LD, Hyde J, et al. Education. The pseudoscience of single-sex schooling. Science. 2011;333(6050):1706–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey C, Huisman T, de Jong RM, Hwang M. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound and elastography imaging of the neonatal brain: a review. J Neuroimaging. 2017;27(5):437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto Y, Ito T, Takada E, Omoto K, Hirai T, Moriyasu F. Efficacy of sonazoid (perflubutane) for contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the differentiation of focal breast lesions: phase 3 multi-center clinical trial. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(4):W400–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lekht I, Gulati M, Nayyar M, Katz MD, ter-Oganesyan R, Marx M, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in evaluation of thermal ablation zone. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(8):1511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao M, Tang J, Liu K, Yang M, Liu H. Quantitative evaluation of vascular microcirculation using contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging in rabbit models of choroidal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(3):1251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ran L, Zhao W, Zhao Y, Bu H. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in differential diagnosis of solid lesions of pancreas (SLP): a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(28):e7463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei X, Li Y, Zhang S, Xin XJ, Zhu L, Gao M. The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the early assessment of microvascularization in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma treated by rituximab-CHOP: a preliminary study. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2014;58(2):363–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo S, Xu P, Zhou A, Wang G, Chen W, Mei J, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound differentiation between low- and high- grade bladder urothelial carcinoma and correlation with tumor microvessel density. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(11):2287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Onofrio M, Crosara S, De Robertis R, Canestrini S, Mucelli RP. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of focal liver lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(1):W56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1208–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neal D, Cohen T, Peterson C, Barr RG. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation of renal tumors. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2018;5(1):7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du J, Li H-L, Zhai B, Chang S, Li F-H. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: utility of conventional ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in guiding and assessing early therapeutic response and short-term follow-up results. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41(9):2400–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou XD, Ren XL, Zhang J, He GB, Zheng MJ, Tian X, et al. Therapeutic response assessment of high intensity focused ultrasound therapy for uterine fibroid: utility of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62(2):289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng S, Hu L, Chen W, Chen J, Yang C, Wang X, et al. Intraprocedure contrast enhanced ultrasound: the value in assessing the effect of ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound ablation for uterine fibroids. Ultrasonics. 2015;58:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W, Li JM, He W, Pan XM, Jin ZQ, Liang T, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for benign breast lesions: evaluated by contrast-enhanced ultrasound combined with magnetic resonance imaging. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(11):4767–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CN, Liang P, Yu J, Yu XL, Cheng ZG, Han ZY, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation of renal cell carcinoma that is inconspicuous on conventional ultrasound. Int J Hyperth. 2016;32(6):607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Liang P, Yu J, Yu XL, Liu FY, Cheng ZG, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluating the efficiency of ultrasound guided percutaneous microwave ablation in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47(4):398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garbajs M, Popovic P. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for assessment of therapeutic response after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of small renal tumors. J BUON. 2016;21(3):685–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barwari K, Wijkstra H, van Delden OM, de la Rosette JJ, Laguna MP. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the evaluation of the cryolesion after laparoscopic renal cryoablation: an initial report. J Endourol. 2013;27(4):402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz E, Hevia V, Arias F, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS): an excellent tool in the follow-up of small renal masses treated with cryoablation. Curr Urol Rep. 2015;16(1):469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Poel HG, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Cornford P, Govorov A, Henry AM, et al. Focal therapy in primary localised prostate cancer: the European Association of Urology position in 2018. Eur Urol. 2018;74(1):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coleman JA, Scardino PT. Targeted prostate cancer ablation: energy options. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23(2):123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madersbacher S, Pedevilla M, Vingers L, Susani M, Marberger M. Effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound on human prostate cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 1995;55(15):3346–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beerlage HP, van Leenders GJ, Oosterhof GO, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) followed after one to two weeks by radical retropubic prostatectomy: results of a prospective study. Prostate. 1999;39(1):41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Leenders GJ, Beerlage HP, Ruijter ET, de la Rosette JJ, van de Kaa CA. Histopathological changes associated with high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment for localised adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53(5):391–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delon-Martin C, Vogt C, Chignier E, Guers C, Chapelon JY, Cathignol D. Venous thrombosis generation by means of high-intensity focused ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1995;21(1):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zlotta AR, Djavan B, Matos C, Noel JC, Peny MO, Silverman DE, et al. Percutaneous transperineal radiofrequency ablation of prostate tumour: safety, feasibility and pathological effects on human prostate cancer. Br J Urol. 1998;81(2):265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saksena M, Gervais D. Percutaneous renal tumor ablation. Abdom Imaging. 2008;34(5):582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeCastro GJ, Gupta M, Badani K, Hruby G, Landman J. Synchronous cryoablation of multiple renal lesions: short-term follow-up of patient outcomes. Urology. 2010;75(2):303–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakada SY, Lee FT Jr, Warner TF, Chosy SG, Moon TD. Laparoscopic renal cryotherapy in swine: comparison of puncture cryotherapy preceded by arterial embolization and contact cryotherapy. J Endourol. 1998;12(6):567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stephenson RA, King DK, Rohr LR. Renal cryoablation in a canine model. Urology. 1996;47(5):772–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davalos RV, Mir IL, Rubinsky B. Tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(2):223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang H, Zhu ZQ, Zhou ZG, Chen LS, Zhao M, Zhang Y, et al. Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound for prediction of prostate cancer aggressiveness: the role of normal peripheral zone time-intensity curves. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russo G, Mischi M, Scheepens W, De la Rosette JJ, Wijkstra H. Angiogenesis in prostate cancer: onset, progression and imaging. BJU Int. 2012;110(11c):E794–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McClure P, Elnakib A, El-Ghar MA, et al. <I>in-vitro</I> and <I>in-vivo</I> diagnostic techniques for prostate Cancer: a review. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(10):2747–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bigler SA, Deering RE, Brawer MK. Comparison of microscopic vascularity in benign and malignant prostate tissue. Hum Pathol. 1993;24(2):220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ismail M, Petersen RO, Alexander AA, Newschaffer C, Gomella LG. Color doppler imaging in predicting the biologic behavior of prostate cancer: correlation with disease-free survival. Urology. 1997;50(6):906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wildeboer RR, Postema AW, Demi L, Kuenen MPJ, Wijkstra H, Mischi M. Multiparametric dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of prostate cancer. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(8):3226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wink M, Frauscher F, Cosgrove D, Chapelon JY, Palwein L, Mitterberger M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound and prostate cancer; a multicentre European research coordination project. Eur Urol. 2008;54(5):982–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quaia E Microbubble ultrasound contrast agents: an update. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(8):1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claudon M, Dietrich CF, Choi BI, Cosgrove DO, Kudo M, Nolsøe CP, et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver - update 2012: a WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39(2):187–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sedelaar JPM, van Leenders GJLH, Hulsbergen van de Kaa CA, et al. Microvessel density: correlation between contrast ultrasonography and histology of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2001;40(3):285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seitz M, Gratzke C, Schlenker B, Buchner A, Karl A, Roosen A, et al. Contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasound (CE-TRUS) with cadence-contrast pulse sequence (CPS) technology for the identification of prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2011;29(3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aigner F, Pallwein L, Mitterberger M, Pinggera GM, Mikuz G, Horninger W, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography using cadence-contrast pulse sequencing technology for targeted biopsy of the prostate. BJU Int. 2009;103(4):458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao H-X, Xia C-X, Yin H-X, Guo N, Zhu Q. The value and limitations of contrast-enhanced transrectal ultrasonography for the detection of prostate cancer. Eur JRadiol. 2013;82(11):e641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie SW, Li HL, Du J, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with contrast-tuned imaging technology for the detection of prostate cancer: comparison with conventional ultrasonography. BJU Int. 2012;109(11):1620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halpern EJ, Gomella LG, Forsberg F, McCue PA, Trabulsi EJ. Contrast enhanced transrectal ultrasound for the detection of prostate cancer: a randomized, double-blind trial of dutasteride pretreatment. J Urol. 2012;188(5):1739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.•. Rouviere O, Glas L, Girouin N, et al. Prostate cancer ablation with transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound: assessment of tissue destruction with contrast-enhanced US. Radiology. 2011;259(2): 583–91. This study showed that CeTRUS is able to demonstrate tissue ablation immediately and up to 1.5 months after whole gland HIFU therapy.

- 58.Sano F, Uemura H. The utility and limitations of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Sensors. 2015;15(3):4947–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu Y, Chen Y, Jiang J, Wang R, Zhou Y, Zhang H. Contrast-enhanced harmonic ultrasonography for the assessment of prostate cancer aggressiveness: a preliminary study. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11(1):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.•. de Castro Abreu AL, Ashrafi AN, Gill IS, et al. Contrast-enhanced Transrectal Ultrasound (CeTRUS) for Follow-up After Focal Ablation of Prostate: Case Series. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2018. 10.1002/jum.14765. In this series, CeTRUS was used intra- and post-operatively with 12 months follow-up demonstrating good correlation with prostate biopsy and mpMRI. This was the first series evaluating CeTRUS following focal ablation with HIFU.

- 61.Liu J-B, Merton DA, Wansaicheong G, Forsberg F, Edmonds PR, Deng XD, et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasound for radio frequency ablation of canine prostates: initial results. J Urol. 2006;176(4):1654–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J-B, Wansaicheong G, Merton DA, Chiou SY, Sun Y, Li K, et al. Canine prostate: contrast-enhanced US-guided radiofrequency ablation with urethral and neurovascular cooling—initial experience. Radiology. 2008;247(3):717–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng HL, Haider MA, Dill-Macky MJ, Sweet JM, Trachtenberg J, Gertner MR. MRI and contrast-enhanced ultrasound monitoring of prostate microwave focal thermal therapy: an in vivo canine study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(1):136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shoji S, Uchida T, Nakamoto M, Kim H, de Castro Abreu AL, Leslie S, et al. Prostate swelling and shift during high intensity focused ultrasound: implication for targeted focal therapy. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muller BG, van den Bos W, Brausi M, Futterer JJ, Ghai S, Pinto PA, et al. Follow-up modalities in focal therapy for prostate cancer: results from a Delphi consensus project. World J Urol. 2015;33(10):1503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rouviere O Imaging techniques for local recurrence of prostate cancer: for whom, why and how? Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93(4):279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Notley M, Yu J, Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Cockrell CH, Nguyen D. Diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer and its mimics at multiparametric prostate MRI. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1054):20150362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Visschere PJ, De Meerleer GO, Futterer JJ, Villeirs GM. Role of MRI in follow-up after focal therapy for prostate carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1427–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim CK, Park BK, Lee HM, Kim SS, Kim E. MRI techniques for prediction of local tumor progression after high-intensity focused ultrasonic ablation of prostate cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(5):1180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sedelaar JP, Aarnink RG, van Leenders GJ, et al. The application of three-dimensional contrast-enhanced ultrasound to measure volume of affected tissue after HIFU treatment for localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2000;37(5):559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sosnowski R, Zagrodzka M, Borkowski T. The limitations of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging also must be borne in mind. Cent European J Urol. 2016;69(1):22–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kirkham AP, Emberton M, Hoh IM, Illing RO, Freeman AA, Allen C. MR imaging of prostate after treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Radiology. 2008;246(3):833–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rouviere O, Lyonnet D, Raudrant A, et al. MRI appearance of prostate following transrectal HIFU ablation of localized cancer. Eur Urol. 2001;40(3):265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rouviere O, Girouin N, Glas L, et al. Prostate cancer transrectal HIFU ablation: detection of local recurrences using T2-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(1):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wondergem N, Rosette JJMCHDL. HIFU and cryoablation – non or minimal touch techniques for the treatment of prostate cancer. Is there a role for contrast enhanced ultrasound? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2007;16(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Apfelbeck M, Clevert DA, Ricke J, Stief C, Schlenker B. Contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) with MRI image fusion for monitoring focal therapy of prostate cancer with high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)1. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2018;69:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pieters B, Wijkstra H, Herk MV, et al. Clinical Investigations Contrast-enhanced ultrasound as support for prostate brachytherapy treatment planning. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2012;2:69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.•. Beyer LP, Pregler B, Nießen C, Michalik K, Haimerl M, Stroszczynski C, et al. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation (IRE) of prostate cancer: contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) findings during follow up. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2017;64(3):501–6. This retrospective study demonstrated the utility of CeTRUS in assessing efficacy of focal IRE therapy up to 6 months after treatment.

- 79.•. van den Bos W, de Bruin DM, van Randen A, Engelbrecht MR, Postema AW, Muller BG, et al. MRI and contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging for evaluation of focal irreversible electroporation treatment: results from a phase I-II study in patients undergoing IRE followed by radical prostatectomy. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(7):2252–60. This prospective study of 12 patients showed good correlation between CeTRUS and histopathology.

- 80.Niessen C, Jung EM, Beyer L, et al. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation (IRE) of prostate cancer: Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) findings. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2015;61(2):135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]