Abstract

The in vitro development of resistance to the new nonfluorinated quinolones (NFQs; PGE 9262932, PGE 4175997, and PGE 9509924) was investigated in Staphylococcus aureus. At concentrations two times the MIC, step 1 mutants were isolated more frequently with ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin (9.1 × 10−8 and 5.7 × 10−9, respectively) than with the NFQs, gatifloxacin, or clinafloxacin (<5.7 × 10−10). Step 2 and step 3 mutants were selected via exposure of a step 1 mutant (selected with trovafloxacin) to four times the MICs of trovafloxacin and PGE 9262932. The step 1 mutant contained the known Ser80-Phe mutation in GrlA, and the step 2 and step 3 mutants contained the known Ser80-Phe and Ser84-Leu mutations in GrlA and GyrA, respectively. Compared to ciprofloxacin, the NFQs were 8-fold more potent against the parent and 16- to 128-fold more potent against the step 3 mutants. Mutants with high-level NFQ resistance (MIC, 32 μg/ml) were isolated by the spiral plater-based serial passage technique. DNA sequence analysis of three such mutants revealed the following mutations: (i) Ser84-Leu in GyrA and Glu84-Lys and His103-Tyr in GrlA; (ii) Ser-84Leu in GyrA, Ser52-Arg in GrlA, and Glu472-Val in GrlB; and (iii) Ser84-Leu in GyrA, Glu477-Val in GyrB, and Glu84-Lys and His103-Tyr in GrlA. Addition of the efflux pump inhibitor reserpine (10 μg/ml) resulted in 4- to 16-fold increases in the potencies of the NFQs against these mutants, whereas it resulted in 2-fold increases in the potencies of the NFQs against the parent.

Bacterial infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens are a major global problem, especially for nosocomial infections (6). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one such pathogen against which options for effective antibacterial therapies are already limited (2). While certain newly developed drugs have promising activity against MRSA (1, 9), their relatively narrow spectra of activity could limit their clinical use in empirical therapy.

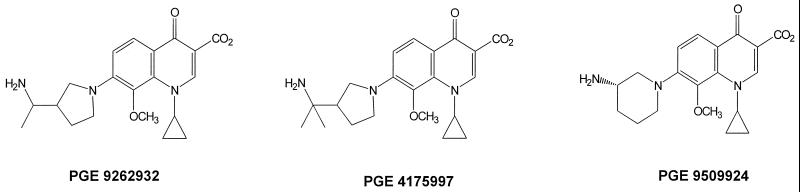

Recently, a series of 8-methoxy, nonfluorinated quinolones (NFQs) (Fig. 1) has been identified as potent antibacterial agents with broad-spectrum antibacterial activities (S. D. Brown, P. C. Fuchs, and A. L. Barry, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1510, p. 210, 2000; B. Ledoussal, J. K. Almstead, S. M. Flaim, C. P. Gallagher, J. L. Gray. X. E. Hu, N. K. Kim, H. D. KcKeever, C. J. Miley, T. L. Twinem, and S. X. Zeng, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-544, p. 303, 1999; D. F. Sahm, A. Staples, I. Critchley, C. Thornsberry, K. Murfitt, and D. Mayfield, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-1509, p. 210, 2000). On the basis of in vitro potency data, these compounds are more potent against MRSA and coagulase-negative staphylococci than several fluoroquinolones and have activities comparable to that of clinafloxacin (10). An apparent advantage of the NFQs against S. aureus lies in their ability to (i) better utilize both DNA gyrase and topisomerase IV as dual targets than certain quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin, and (ii) largely circumvent existing mutations in serine and glutamate “hot spots” of the target genes, gyrA and grlA, commonly associated with quinolone resistance (10, 11). However, it is imperative to ascertain the potential for development of de novo resistance to the NFQs in these pathogens. This report describes the in vitro isolation of S. aureus mutants with reduced susceptibilities to the NFQs and other quinolones by two approaches: stepwise isolation of mutants and spiral plater-based serial passage.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of the NFQs used in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and strains.

The NFQs PGE 9262932, PGE 4175997, and PGE 9509924 and the other quinolones used in the present study were synthesized in-house. PGE 9509924 was used as a racemic mixture for the selection of mutants. Reserpine was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.) and was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (2 mg/ml stock) prior to addition to growth medium. S. aureus Mi273 (ATCC 29213) was used as the parent strain for the selection of mutants.

Stepwise selection of mutants.

S. aureus Mi273 or its mutants were resuspended (1.8 × 109 to 2.3 × 109 CFU) in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth from an overnight culture and plated onto BHI agar plates containing two to four times the MIC of the test compounds (for Mi273 or its mutants), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Control plates with no drug were incubated for 24 h. Two to three agar plates were used to have the desired inoculum exposed to each compound at each concentration. Following incubation, the bacterial colonies were counted to obtain the mutation frequencies. Selected colonies were subcultured onto BHI agar and stored as frozen cultures in 20% glycerol. These mutants were subsequently used to generate next-step mutants by the procedure described above. At each step of mutant isolation, the MICs of the NFQs and the benchmark quinolones were determined for the mutants.

Serial passage.

S. aureus Mi273 was grown on petri dishes with Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar and 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), transferred to a tube containing sterilized brucella broth, and adjusted to an optical density of 0.4 at 600 nm. Compounds were prepared at 50 μg/ml, 500 μg/ml, 5 mg/ml, and 25 mg/ml and were dispensed with a spiral plater (model 4000; Spiral Biotech, Inc.) onto MH agar-blood agar petri dishes to generate a concentration gradient. The petri dishes were inoculated in quadruplicate (referred to as replicates 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the Results section) with the broth cultures mentioned above.

The petri dishes were incubated for 48 h in a 37°C incubator to maximize the growth of resistant organisms. End points were measured with a spiral gradient end point grid template. The end point was measured as the point at which confluent growth was noticeably reduced, denoted as the tail beginning radius. The end point of growth was entered into the spiral gradient end point software, along with the depth of the agar and the molecular weight of the antibiotic. The agar depth and molecular weight were used to calculate a concentration gradient across the plate. The drug concentration at the point where the tail beginning radius is located is denoted as the minimum activity concentration. The gradient MIC is the first, higher twofold value above this concentration and is the measurement reported. Cells growing at the transition area of growth to no growth were used to inoculate a fresh MH agar-blood agar petri dish, and the petri dish was incubated for 24 h to maximize the biomass for subsequent inoculum preparation and passage on drug-containing media. The organisms were passaged 10 times or until the MIC was too high to be measured.

To analyze the target DNA sequence of S. aureus Mi273 and its mutants, segments of the target genes, gyrA, gyrB, grlA, and grlB, including the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs), were amplified by PCR with appropriate primers. The DNA sequences of the PCR products were determined with an Applied Biosystems automatic DNA sequencer. The DNA sequences were obtained for regions encoding Pro-36 through Gly-174 for GyrA, Arg-400 through Ile-531 for GyrB, Gly-37 through Asp-112 for GrlA, and Ser-398 through Val-527 for GrlB. Both strands of DNA were sequenced. Analysis of serial passage-selected mutants (strains 273/932-2, 273/997-3, and 273/924-3) was repeated.

MICs.

The MICs of the test compounds were determined by incubating cultures (∼5 × 105 CFU/ml) of Mi273 and its mutants overnight (18 to 24 h) at 37°C in BHI broth in the presence of test compounds in a twofold broth microdilution series in duplicate. The MIC was recorded as the minimum concentration of the test compound required for complete inhibition of bacterial growth. MICs in the presence of reserpine (10 μg/ml) were measured by the same broth microdilution method, and all the data were generated in duplicate.

RESULTS

Stepwise selection of mutants.

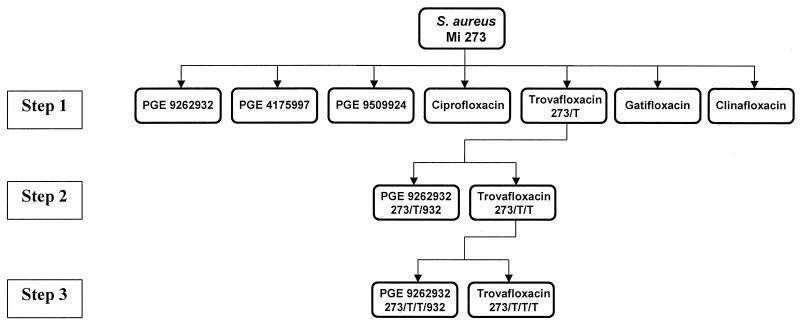

S. aureus mutants capable of growing in the presence of concentrations two times above the MIC were isolated at frequencies of 9.1 × 10−8 and 5.7 × 10−9 for ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin, respectively, and <5.7 × 10−10 for the NFQs, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin. These mutants were termed step 1 mutants (Fig. 2). One of these mutants (strain 273/T), selected with trovafloxacin, was analyzed for quinolone susceptibility and the DNA sequence of the QRDR. As shown in Table 1, strain 273/T contained the known Ser80-Phe mutation in GrlA. The MICs for this strain relative to those for the parent were twofold higher for the NFQs, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin and eight- and fourfold higher for ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin, respectively (Table 2). The susceptibilities of 17 additional step 1 mutants (5 selected with trovafloxacin and 12 selected with ciprofloxacin) to the NFQs and the other quinolones tested were similar to that of strain 273/T (the MICs were within 1 twofold dilution range; data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the stepwise selection of mutants via exposure to the NFQs, ciprofloxacin, trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin. Details of the experiment are described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 1.

Agents used for stepwise selection and genotypes of stepwise-selected mutants of S. aureus Mi273

| Strain | Isolation step | Selecting agent | Mutation detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mi273 | None | ||

| 273/T | 1 | Trovafloxacin | S80-F (GrlA) |

| 273/T/T | 2 | Trovafloxacin, trovafloxacin | S84-L (GyrA), S80-F (GrlA) |

| 273/T/932 | 2 | Trovafloxacin, PGE 9262932 | S84-L (GyrA), S80-F (GrlA) |

| 273/T/T/T | 3 | Trovafloxacin, trovafloxacin, trovafloxacin | S84-L (GyrA), S80-F (GrlA) |

| 273/T/T/932 | 3 | Trovafloxacin, trovafloxacin, PGE 9262932 | S84-L (GyrA), S80-F (GrlA) |

TABLE 2.

In vitro susceptibilities of stepwise-selected mutants of S. aureus Mi273

| Quinolone | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mi273 | 273/T | 273/T/T | 273/T/932 | 273/T/T/T | 273/T/T/932 | |

| PGE 9262932 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 |

| PGE 4175997 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 |

| PGE 9509924 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 32 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.063 | 0.25 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.125 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Clinafloxacin | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

Strain 273/T was used to select step 2 mutants via exposure to the NFQs and the other quinolones. Strains 273/T/T and 273/T/932, isolated at this step with trovafloxacin and PGE 9262932, respectively, were studied further and were found to contain the Ser84-L mutation in GyrA, in addition to the Ser80-F mutation in GrlA found in step 1 mutant 273/T (Table 1). The MICs for these step 2 mutants relative to those for their step 1 parent (strain 273/T) were 2- to 4-fold higher for the NFQs, ciprofloxacin, and clinafloxacin and 8- and 16-fold higher for trovafloxacin and gatifloxacin, respectively. Next, strain 273/T/T was used to select step 3 mutants via exposure to the NFQs and the other quinolones tested. Strains 273/T/T/T and 273/T/T/932, isolated at this step with trovafloxacin and PGE 9262932, respectively, were found to contain the same mutations (Ser80-F in GrlA and Ser84-L in GyrA) found in the step 2 mutants (Table 1). The MICs for step 3 mutant 273/T/T/T (selected with trovafloxacin) were one- to twofold higher for the NFQs, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin and four- and eightfold higher for ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin, respectively, relative to those for step 2 parent 273/T/T. The MICs for step 3 mutant 273/T/T/932 (selected with PGE 9262932) were two- to fourfold higher for the NFQs and ciprofloxacin and were unchanged for trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin relative to those for step 2 parent 273/T/T. Relative to the MICs for the original parent strain, strain Mi273, the overall increases in the MICs for the step 3 mutants were 14-fold (geometric mean) for the NFQs and clinafloxacin and 64-fold (geometric mean) for ciprofloxacin, trovafloxacin, and gatifloxacin. The potential role of efflux in quinolone susceptibility in these strains was ascertained by monitoring the increase in potency due to the addition of the known efflux pump inhibitor reserpine (10 μg/ml) (4). The addition of reserpine resulted in comparable decreases in the MICs of all seven quinolones tested for the parent strain and the step 1, step 2, and step 3 mutants (geometric mean decreases, 2-, 1.8-, 1.7-, and 1.6-fold, respectively).

Serial passage.

The results of the serial passage experiments are presented in Table 3. Among all the quinolones tested, susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was reduced the most within four passages, and the final MIC for all the four strains was >128 μg/ml, as determined by the broth dilution method. All four strains isolated via exposure to trovafloxacin remained relatively susceptible to it (final MIC range, 0.5 to 2.0 μg/ml). Similar mutants isolated with gatifloxacin and clinafloxacin showed variable susceptibilities to these compounds (final MIC ranges, 1 to 32 and 1 to 16 μg/ml, respectively). Susceptibilities to the NFQs were reduced to various degrees, with final MICs being in the range of 1 to 64 μg/ml. Significant reductions in susceptibilities were seen after seven passages with subinhibitory levels of the NFQs, clinafloxacin, and gatifloxacin.

TABLE 3.

In vitro susceptibilities of the S. aureus parent strain and mutants following 10 serial passages

| Selecting agent | Initial MIC (μg/ml) | Final MIC (μg/ml) for replicate:

|

Fold Increase in MIC for replicate:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| PGE 9262932 | 0.063 | 16 | 32 | 1 | 1 | 256 | 512 | 16 | 16 |

| PGE 4175997 | 0.063 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 512 | 512 |

| PGE 9509924a | 0.125 | 16 | 2 | 64 | 16 | 128 | 16 | 512 | 128 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.125 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25 | 16 | 32 | 8 | 1 | 64 | 128 | 32 | 4 |

| Clinafloxacin | 0.063 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 32 | 256 | 128 | 16 |

The racemic form was used for the selection of mutants and the MIC analysis.

Analysis of the NFQ-resistant mutants.

To elucidate the molecular basis for reduced susceptibility to the NFQs, partial DNA sequences of the target genes of some of the mutants described above were analyzed. The results are presented in Table 4. The point mutations identified include (i) those in the known hot spots in the QRDR, such as Ser84-Leu in GyrA and Glu84-Lys in GrlA (11), and (ii) those that were previously unknown, such as His103-Tyr and Ser52-Arg in GrlA, Glu477-Val in GyrB, and Glu472-Val in GrlB. The MICs of the other quinolones tested for these mutants (relative to those for the parent strain Mi273 [Table 3]) were also elevated (Table 5). The potencies of the NFQs against strains 273/932-2 and 273/924-3 (MICs, 16 to 32 μg/ml; geometric mean MIC, 28.5 μg/ml) were higher than those of ciprofloxacin (MICs, >128 μg/ml) and overall were comparable to those of trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin (MICs, 16 to 128 μg/ml; geometric mean MIC, 32 μg/ml). In contrast, the potencies of the NFQs against strain 273/997-3 (MICs, 8 to 32 μg/ml; geometric mean MIC, 20.1 μg/ml) were overall lower than those of the other quinolones tested (MICs 2 to 16 μg/ml; geometric mean MIC, 4.8 μg/ml).

TABLE 4.

Selecting agents and genotypes of S. aureus Mi273 mutants selected via serial passage

| Selecting agent | Strain | Mutation detected |

|---|---|---|

| PGE 9262932 | 273/932-2 | S84-L (GyrA), E84-K and H103-Y (GrlA) |

| PGE 4175997 | 273/997-3 | S84-L (GyrA), S52-R (GrlA), E472-V (GrlB) |

| PGE 9509924a | 273/924-3 | S84-L (GyrA), E477-A (GyrB), E84-A and H103-Y (GrlA) |

The racemate form was used for the selection of mutants.

TABLE 5.

Cross-resistance of the NFQ-selected mutants of S. aureus Mi273 to other quinolones

| Quinolone | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 273/932-2 | 273/997-3 | 273/924-3 | |

| PGE 9262932 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| PGE 4175997 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| PGE 9509924a | 32 | 8 | 32 |

| Ciprofloxacin | >128 | 16 | >128 |

| Trovafloxacin | 16 | 2 | 16 |

| Gatifloxacin | 128 | 8 | 64 |

| Clinafloxacin | 32 | 2 | 16 |

The racemate form was used for the selection of mutants.

Next, the potential role of efflux in the quinolone resistance of these strains relative to that of the parent was ascertained by monitoring the increase in potency due to the addition of reserpine. As shown in Table 6, the increases in the potencies of the NFQs due to the addition of reserpine were higher against these mutants (increase in the geometric mean MIC, eightfold) than against the parent (increase in the geometric mean MIC, twofold). The corresponding increases in the potencies of trovafloxacin and gatifloxacin were two- to fourfold against these mutants and one- to twofold against the parent.

TABLE 6.

Increase in potency against mutants due to the putative inhibition of efflux

| Strain | Fold decrease in MIC due to the addition of reserpine at 10 μg/ml

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mi273 (parent) | 273/932-2 | 273/997-3 | 273/924-3 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 | >1a | 8 | >1a |

| Trovafloxacin | 1–2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 1–2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Clinafloxacin | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| PGE 9262932 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| PGE 4175997 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| PGE 9509924 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Ethidium bromide | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

The MICs of ciprofloxacin were >128 and 128 μg/ml without and with reserpine, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, two approaches were used to select NFQ-resistant mutants of S. aureus. First, the stepwise isolation of S. aureus mutants via exposure to drugs at concentrations above the MIC was attempted. The frequency of mutant selection was lower when S. aureus was exposed to two times the MICs of the NFQs, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin (<5.7 × 10−10) than when it was exposed to ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin (9.1 × 10−8 and 5.7 × 10−9, respectively). These data are consistent with those from previous work (10), suggesting that the former group of quinolones is better able to utilize both DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV as dual targets in S. aureus at the whole-cell level. However, when a step 1 mutant (strain 273/T) containing the Ser80-F mutation in GrlA was exposed to all the quinolones used in the present study at four times the MICs, mutants were selected in each case.

The results, presented in Tables 1 and 2, indicate that the mutations in the QRDRs and the levels of quinolone susceptibility of the step 2 mutants were similar for both strains, irrespective of the selecting agent. Additional step 2 mutants isolated with the other two NFQs, PGE 4175997 and PGE 9509924, had similar quinolone susceptibility profiles (data not shown). Overall, the results obtained with the step 2 mutants suggest that certain common mechanisms of quinolone resistance are selected in these mutants. The step 3 mutants, strains 273/T/T/T and 273/T/T/932, contained the same mutations in their QRDRs as their step 2 parent (strain 273/T/T). However, the quinolone MICs for the step 3 mutants were overall higher than those for the step 2 mutants, suggesting the involvement of additional mechanisms of resistance. On the basis of the MICs for these mutants in the presence of reserpine, higher levels of efflux (relative to that for the parent) did not appear to be involved. Additional step 3 mutants isolated with another NFQ, PGE 4175997, showed similar quinolone susceptibility profiles (data not shown).

By the spiral plater-based serial passage technique, three S. aureus mutants with high-level NFQ resistance (MICs, ∼32 μg/ml) were identified during the study. The susceptibilities of these mutants to the other quinolones tested reveal an interesting pattern. First, the potencies of NFQs against strains 273/932-2 and 273/924-3 (Table 5) were comparable to those of trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin, and clinafloxacin. Second, in strain 273/997-3, the resistance to the NFQs appeared to be more specific than the resistance to the other quinolones tested. These data suggest that the mechanism(s) of quinolone resistance in these mutants is different from that in the stepwise-selected ones, against which the level of NFQ resistance is low (MICs, 0.5 to 2 μg/ml).

DNA sequence analysis of selected segments of the target genes, including the QRDRs of these mutants (strains 273/932-2, 273/997-3, and 273/924-3; Table 4), suggests a possible link between high-level NFQ resistance and multiple point mutations. While point mutations, such as those in the Ser80/84 and Glu84/88 residues of GrlA and GyrA, are frequently encountered in quinolone-resistant MRSA isolates (11), mutations in the His103 or Ser52 residues of GrlA appear to be unique. It is interesting that, unlike the serine and glutamate hot spots, His103 and Ser52 are not well conserved across different bacterial species (3, 7, 8). In addition, these residues fall outside the conventional QRDR in S. aureus (3). Recently, several novel mutations outside the QRDR were also found to be associated with resistance to premafloxacin in S. aureus (5). However, the specific roles of individual mutations in NFQ resistance can be determined only by further research, including introduction of the unique mutations in a sensitive S. aureus strain. In addition, point mutations in the target genes may not be solely responsible for high-level NFQ resistance. The data presented in Table 6, which show an eightfold increase in the potencies of NFQs against these mutants due to the addition of reserpine (compared with a twofold increase in potencies against the parent), suggest a possible role of putative efflux mechanisms, in addition to target mutations, in NFQ resistance.

Overall, the two sets of S. aureus mutants isolated during the present study revealed two different patterns of quinolone susceptibility. First, as previously observed with the MRSA isolates (10), stepwise-selected mutants with known mutations in GyrA and GrlA were relatively susceptible to the NFQs and clinafloxacin in vitro (MICs, 1 to 2 μg/ml). Second, additional mutants that were isolated via serial passage and that had high-level NFQ resistance harbored multiple, known, and unique mutations in both targets, combined with an apparently elevated level of efflux.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. D. Leunk, K. S. Howard-Nordan, W. L. Seibel, J. J. Ares, and D. W. Axelrod for critical reading of the manuscript and managerial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allington D R, Rivey M P. Quinupristin/dalfopristin: a therapeutic review. Clin Ther. 2001;1:24–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daum R S, Seal J B. Evolving antimicrobial chemotherapy for Staphylococcus aureus infections: our backs to the wall. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(Suppl. 4):N92–N96. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Langeaux D, Crouzet J, Famechon A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbons S, Udo E E. The effect of reserpine, a modulator of multidrug efflux pumps, on the in vitro activity of tetracycline against clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) possessing the Tet(K) determinant. Phytother Res. 2000;14:139–140. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(200003)14:2<139::aid-ptr608>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ince D, Hooper D C. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3344–3350. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3344-3350.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones R N. Resistance patterns among nosocomial pathogens: trends over the past few years. Chest. 2001;119(Suppl. 2):397S–404S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.2_suppl.397s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry C M, Jarvis B. Linezolid: a review of its use in the management of serious gram-positive infections. Drugs. 2001;61:525–551. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roychoudhury S, Catrenich C E, McIntosh E J, McKeever H D, Makin K M, Koenigs P M, Ledoussal B. Quinolone resistance in staphylococci: activities of new nonfluorinated quinolones against molecular targets in whole cells and clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1115–1120. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1115-1120.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Tanaka M, Sato K. Detection of grlA and gyrA mutations in 344 Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:236–240. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]