Abstract

Background and Objectives:

One of the major causes of urinary tract infections is Klebsiella pneumoniae. Currently, few studies investigated the mechanisms of resistance to colistin in Iran. The current study aimed to determine the prevalence of plasmid and chromosome-mediated resistance to colistin in K. pneumoniae isolates.

Materials and Methods:

177 urine samples were collected from patients with urinary tract infections hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU) of hospitals in the city of Qazvin. K. pneumoniae isolates were identified by standard biochemical methods, resistance to colistin among K. pneumoniae isolates were tested by disk diffusion and microbroth dilution methods. The chromosomal mutation and presence of the mcr genes in colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae were evaluated by PCR.

Results:

Out of 177 samples, 65 K. pneumoniae were obtained from patients in the ICU. Six colistin-resistant isolates were isolated with MIC values ≥4 μg/mL, none of them was positive for mcr1-5. In 4 isolates, missense mutation in mgrB gene resulted in amino acid substitutions and in one isolate of mgrB gene was found intact mgrB gene.

Conclusion:

The results suggest that mgrB mutation was the main mutation among colistin-resistant isolates and plasmid-borne colistin resistance was not expanded among strains.

Keywords: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Colistin, MgrB, Mcr gene, Intensive care units

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, due to the emergence of new infections and the spread of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (MDR), the lives of many patients have been threatened and financial costs of health systems have substantially increased all around the world. Parallel to the increase in antibiotic resistance, particularly among members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, therapeutic abscesses were restricted and few new drugs were developed (1). Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the major causes of nosocomial infections that can carry many antibiotic resistance genes such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), and because of the production of these enzymes, the use of third and fourth generation cephalosporins is restricted and therefore carbapenems were started to use (2, 3). K. pneumoniae is also resistant to these drugs (carbapenems) by plasmid-mediated carbapenemase production (2, 3). Cationic polymyxin antibiotics (polymyxin B and colistin), which were discarded in the 1970s due to high nephrotoxicity, were re-entered to the market by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 as medication for MDR Gram-negative bacteria, particularly carbapenem-producing Enterobacteriaceae. The last line of drug therapy was used for these patients. These antibiotics establish a strong electrostatic bond with the outer membrane (LPS) of the bacterium, causing disruption of the entire LPS structure, and reduces the integrity and increases the membrane permeability, and ultimately leads to bacterial cell death (4–6). Colistin resistance is mainly dependent on the change in the LPS of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, which reduces by the addition of the positive charge molecules L-Ara4-N and PetN, which in turn reduces the bacterial membrane negative charge and consequently decreases the membrane response to colistin (7, 8). These changes are due to mutations in the two-part regulatory systems and most of the mutations occur in the genes mgrB, phoP/Q, pmrA/B, pmrC, crrABC (9). By 2015, polymyxin resistance was thought to occur only through chromosomal mutations between the genes regulating pmrA/B and phoP/Q binary systems, or mutations in the mgrB gene (10–14). The mechanisms involved in colistin resistance are shown in Fig. 1. The recent discovery of the plasmid-dependent mcr-1 gene in Escherichia coli by Liu in 2015 (15) in China revealed another form of resistance to colistin. This gene is based on moving genetic elements and due to horizontal gene transfer; it has caused resistance and therefore spread throughout the world. Following the discovery of mcr-1, other genes such as mcr-2 and subsequently, mcr-3, mcr-4, mcr-5, mcr-6, mcr-7, mcr-8 were reported. The current study aimed to evaluate the molecular mechanisms of colistin-resistance among urinary isolates of K. pneumoniae isolated from patients admitted to the ICU of the three hospitals in West Iran (Qazvin).

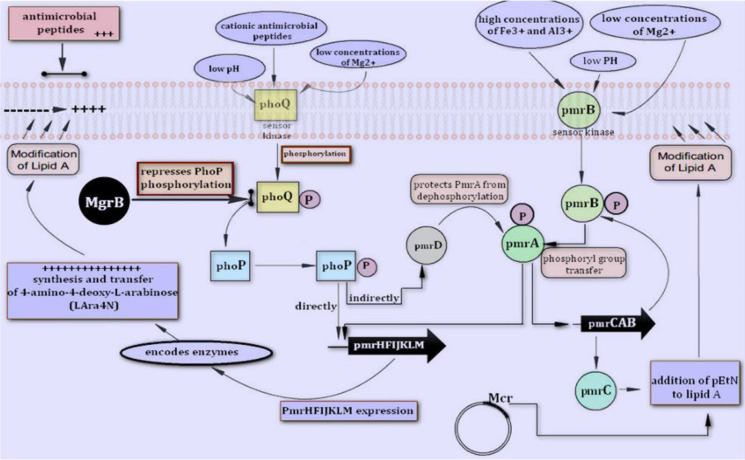

Fig. 1.

Proteins and genes involved in the regulatory network modulating chemical modifications of the lipid a moiety on the lipopolysaccharide with L-Ara4N and pEtNand Mcr in K. pneumoniae. Two-component systems PmrA/PmrB and PhoP/PhoQ are activated by environmental stimuli and regulate the transcription of genes pmrHFIJKLM and pmrC via phosphorylation of the cognate response regulators PmrA and PhoP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection, processing, and identification.

From November 2017 to October 2018, 65 non-duplicated clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae from 177 samples were collected from microbiology laboratories of the three hospitals in West Iran (Qazvin). The samples were isolated from the urine of patients with urinary tract infections. They were then immediately transferred to the laboratory of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences for further analysis. All specimens were sub-cultured on MacConkey Agar (Merck, Germany). After incubation of the plates at 37°C for 24 h, the colonies were identified and confirmed as K. pneumoniae using biochemical tests (API-10S system, bioMérieux, France). The isolates were stored in Tryptic Soy Broth (BDTM. Germany) with 20% glycerol at −80°C until further analysis.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method, as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2020) guidelines, was performed to determine antimicrobial susceptibility. Thirteen antibiotics including colistin (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime-clavulanic acid (40 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefotaxime-clavulanic acid (40 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), nitrofurantoin (300 μg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (25 μg), and cefoxitin (30 μg) were used and the results were compared with the CLSI 2020 guidelines. In addition, Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were classified as MDR, XDR, and ESBL according to the proposal for Interim Standards Guidelines (15).

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for colistin.

Colistin resistance was phenotypically detected by broth micro-dilution method (BMD), using colistin sulphate powder (Sigma–Aldrich). Then, results were interpreted according to the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2020) guidelines. Thereafter, isolates with MIC ≥4 μg/mL were considered as resistant strains. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as quality control for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and E. coli KP81 as a colistin-resistant strain.

Extraction of DNA and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Genomic DNA of all isolates that were phenotypically confirmed as colistin-resistant, were extracted for molecular analysis by Gspin™ Total DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, a master mix was prepared in a final volume of 25 μL containing 12.5 μL of 2 × Master Mix, 0.5 μL of each primer, 3 μL of extracted DNA as template and 8.5 μL of sterile distilled water. The mcr-1 to mcr-5 genes were amplified byspecific primers (Table 1) and were evaluated as follows: denaturation at 94ºC for 5 min, 25 cycles of denaturation at 94ºC for 1 min, annealing temperatures according to Table 1 and for 30 s, extension at 72ºC for 60 s, and final extension at 72ºC for 60 s. The cycling conditions used for mgrB gene were as follows: denaturation at 94ºC for 5 min, 25 cycles of denaturation at 94ºC for 1 min, annealing at 51ºC for 30 s, extension at 72ºC for 30 s, and final extension at 72ºC for 5 min. The PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5’-3’) | Annealing Temperature (ºC) | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mcr1 | Fw AGTCCGTTTGTTCTTGTGGC | 51 | 320 | (15) |

| Rev AGATCCTTGGTCTCGGCTTG | ||||

| mcr2 | Fw CAAGTGTGTTGGTCGCAGTT | 56 | 715 | (16) |

| Rev TCTAGCCCGACAAGCATACC | ||||

| mcr3 | Fw AAATAAAAATTGTTCCGCTTATG | 57 | 929 | (16) |

| Rev AATGGAGATCCCCGTTTTT | ||||

| mcr4 | Fw TCACTTTCATCACTGCGTTG | 58 | 1,116 | (17) |

| Rev TTGGTCCATGACTACCAATG | ||||

| mcr5 | Fw ATGCGGTTGTCTGCATTTATC | 58 | 1,644 | (18) |

| Rev TCATTGTGGTTGTCCTTTTCTG | ||||

| mgrB | FWGCTCAATAATACGCCAATCC | 51 | 526 | This study |

| ReV CATAACAACAGACCGACAAG |

mcr-1 and mgrB sequence analysis.

For mgrB and mcr-1 genes, sequencing of the PCR products was conducted by Sanger sequencing through an external expertise provider (Macrogen, Korea) (Table 1). Nucleotide sequences obtained by PCR sequencing were compared with sequence databases using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Statistical analysis.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Armonk, North Castle, NY, USA). Descriptive data are shown as frequency and mean.

RESULTS

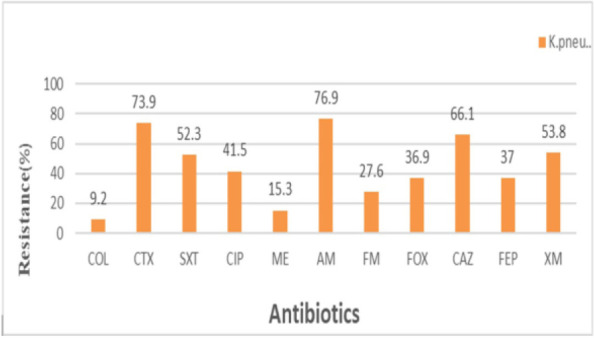

Antibiotic susceptibility results showed that most of the isolates were resistant to ampicillin 77% (50/65), cefotaxime 73.9% (45/65), ceftazidime 66% (43/65), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 52.3% (34/65). Resistance to cefuroxime and ciprofloxacin was 54% (35/65) and 41.5% (27/65). Whereas the lowest resistance rate was observed for cefoxitin 37% (24/65), cefepime 37 (24/65), nitrofurantoin 27.7 (18/65), and meropenem 15.3 (10/65). The detailed percentages for all tested antibiotics are shown in Fig. 2. Out of 65 isolates of K. pneumoniae, two isolates were resistant to colistin by disk diffusion method and sixty-three isolates had a growth inhibition zone greater than 10 mm. For these isolates, sensitivity to colistin was determined by broth micro-dilution method. Colistin resistance was found in 10.7% (6/65) of K. pneumoniae via the broth micro-dilution method. The two isolates that showed resistance to colistin by the disk diffusion method, had MIC greater than 4 μg/mL. Surprisingly, among 63 isolates that were susceptible to colistin in the disk diffusion method, four isolates had MIC greater than 4 μg/mL. For colistin-resistant strains, the MIC values ranged from 4 to 32 μg/ml in K. pneumoniae isolates.

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of K. pneumoniae isolates in this study.

The presence of mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, mcr-5 genes in all isolates of K. pneumoniae of ICU patients was evaluated and none of these genes was observed. The PCR products of mgrB gene for all col-R K. pneumoniae isolates were sequenced to identify chromosomal mutations (Table 2). In one isolate, the mgrB gene was not detected. It indicated the occurrence of a partial or complete deletion of the mgrB gene. In Three isolates, the missense mutation in mgrB genes had led to a change from tryptophan to glycine. In addition, in one isolate, there was a change from isoleucine to phenylalanine in position 45. In five isolates, a similar mutation occurred at nucleotide 42 that did not result in amino acid change and therefore it was not a deleterious mutation. In one isolate (16.6%), a high level of resistance with MIC ≥32 was observed to the antibiotic colistin.

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance profiles and mgrB gene mutations among six colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates in ICU.

| Isolate | MIC for colistin (μg/mL) | Modifications in mgrB | Antibiotic susceptibility profile | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Non-susceptible to: | Susceptible to: | MCR-1-9 | MDR XDR | ESBL | ||||||

| KP1 | 32 | T139g (W47G) | COL, AM, CAZ, | CP, ME, FM, FOX, FEP, XM, CTX, SXT | - | MDR | + | |||

| KP2 | 8 | A133t (I45F) | COL, CTX, AM, FM, FOX, CAZ, FEP, XM | SXT, CP, MEM, | - | MDR | - | |||

| KP3 | 4 | T139g (W47G) | COL, AM, XM | CTX, SXT, CP, MEM, FM, FOX, CAZ, FEP | - | - | - | |||

| KP4 | 4 | T139g (W47G) | COL, CTX, MEM, AM, FOX, CAZ, XM | SXT, CP, FM, FEP | - | - | - | |||

| KP5 | 4 | WT | COL, CTX, SXT, AM, FEP, CAZ, XM | CP, MEM, FM, FOX, | - | MDR | + | |||

| KP6 | 4 | Partial or complete deletion | COL, CTX, SXT, CO, FOX, CAZ, FEP, XM | MEM, FM | - | MDR | - | |||

| No amplification | ||||||||||

DISCUSSION

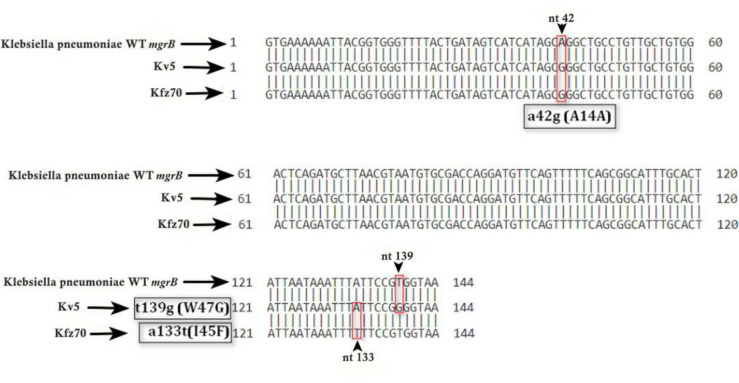

In the present study, 6 colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were detected, with MIC values ranging from 4 to 32 μg/ml. All isolates were obtained from urine samples of ICU patients. Because in the ICU usually the most invasive methods administer, the risk of biofilm formation by these bacteria is higher. The rapid spread of antibiotic resistance among hospitalized patients has become a major health concern in recent years. This issue is particularly obvious in ICU patients, so that almost all patients with infectious diseases were treated with antibiotics. The WHO estimates that the global rate of nosocomial infections among hospitalized patients ranges from 7 to 12% (19, 20). Due to increased resistance to antibiotics, colistin uses as the last line of treatment for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. In evaluating antibiotic susceptibility, the highest percentage of resistance was for ampicillin (77%), cefotaxime (73.9%), and ceftazidime (66%). Conversely, 84.6% of the isolates were susceptible to meropenem, a carbapenem drug class used mainly for infections caused by MDR bacteria. All colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae strains were MDR. In this study, mcr-1 to mcr-5 genes were not detected in any of the K. pneumoniae isolates, thus chromosomal mutations are the cause of resistance. These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted in Iran, which did not detect mcr genes in K. pneumoniae isolates (21–23). These results indicated that the prevalence of plasmid genes related to colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae strains is low in Iran. Of 65 isolates obtained from patients hospitalized in ICU, 6(10.6%) were colistin-resistant, of which four missense mutations in the mgrB gene resulted in amino acid substitution and inactivation of the MgrB and development of colistin resistance. Given that mgrB gene gel electrophoresis results did not show bands larger than predicted, the insertion sequences probably did not play a role in mgrB gene inactivation and confirmed its sequencing results. Whereas in the study of Hillel et al. and Pishnan et al. insertion sequences (IS1-like (768 bp) and IS5-like families (1,056 bp)) was involved in the development of colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates (21–23). Most of the mechanism of mgrB gene inactivation was reported to be due to the insertion of IS into the gene and the promoter region of the gene (24). However, in the current study, no IS induced mgrB gene inactivation was observed. Three W47G substitution isolates were identified in the mgrB gene, which produced a non-functional MgrB and caused resistance to colistin. These changes in the mgrB gene at the same position indicated the occurrence of transverse transfer and clonal expansion in the ICU. These isolates had a mutation in nucleotide 42 that did not result in amino acid alteration. The W47R amino acid substitution is previously reported by Esposito et al. (2018) in Naples (Italy) (25). In this isolate at nucleotide 51, a missense mutation occurred that did not result in an amino acid substitution. In the current study, an I45F amino acid substitution in the mgrB gene was observed, which is also reported by Ghafur et al. (2019) in India (26). This substitution led to the amino acid change from isoleucine to phenylalanine. In one CRKP isolate no PCR product was found, that indicated complete or partial deletion of the mgrB gene and therefore no negative feedback mechanism was applied to the phoP/Q regulatory genes, that is similar to the current study. Several studies have reported the deletion of the mgrB gene (13, 26–30). Mutations and genetic changes in the mgrB gene are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Mutations and genetic alterations in mgrB gene and colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae. The arrow indicates the target site for amino acid changes

In conclusion, the prevalence of colistin-resistance K. pneumoniae is alarmingly increasing in Iran. Besides, the plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene mcr-1 was not detected in isolates, that indicated the gene had not yet been transmitted among the clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae, but according to other studies, regular monitoring is essential to fully understand the molecular mechanisms mediating colistin resistance in human K. pneumoniae isolates. In the current study, we found that mgrB changes (mgrB mutation) play an important role in the resistance to colistin in the isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Iran and the most common type of change in mgrB gene was due to missense mutations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robatjazi S, Nikkhahi F, Niazadeh M, Amin Marashi SM, Peymani A, Javadi A, et al. Phenotypic identification and genotypic characterization of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Iran. Curr Microbiol 2021;78:2317–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh TR. Emerging carbapenemases: a global perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010;36 Suppl 3:S8–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livermore DM, Woodford N. The β-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends Microbiol 2006;14:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grégoire N, Aranzana-Climent V, Magréault S, Marchand S, Couet W. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of colistin. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017;56:1441–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard M, Drusano GL, Vicchiarelli M, Liu W, Myrick J, Nole J, et al. Polymyxin B pharmacodynamics in the hollow-fiber infection model: what you see may not be what you get. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021;16;65(8):e0185320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaara M. New polymyxin derivatives that display improved efficacy in animal infection models as compared to polymyxin B and colistin. Med Res Rev 2018;38:1661–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velkov T, Deris ZZ, Huang JX, Azad MA, Butler M, Sivanesan S, et al. Surface changes and polymyxin interactions with a resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Innate Immun 2014;20:350–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng HY, Chen YF, Peng HL. Molecular characterization of the PhoPQ-PmrD-PmrAB mediated pathway regulating polymyxin B resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. J Biomed Sci 2010;17:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giani T, Arena F, Vaggelli G, Conte V, Chiarelli A, De Angelis LH, et al. Large nosocomial outbreak of colistin-resistant, carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae traced to clonal expansion of an mgrB deletion mutant. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:3341–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain JM. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front Microbiol 2014;5:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannatelli A, D'Andrea MM, Giani T, Di Pilato V, Arena F, Ambretti S, et al. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-type carbapenemases mediated by insertional inactivation of the PhoQ/PhoP mgrB regulator. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:5521–5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunn JS. The Salmonella PmrAB regulon: lipopolysaccharide modifications, antimicrobial peptide resistance and more. Trends Microbiol 2008;16:284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikkhahi F, Robatjazi S, Niazadeh M, Javadi A, Shahbazi GH, Aris P, et al. First detection of mobilized colistin resistance mcr-1 gene in Escherichia coli isolated from livestock and sewage in Iran. New Microbes New Infect 2021;41:100862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebelo AR, Bortolaia V, Kjeldgaard JS, Pedersen SK, Leekitcharoenphon P, Hansen IM, et al. Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinants, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 for surveillance purposes. Euro Surveill 2018;23:17–00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, et al. Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2006;27:351–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bardet L, Rolain JM. Development of new tools to detect colistin-resistance among Enterobacteriaceae strains. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2018;2018:3095249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azimi A, Peymani A, Pour PK. Phenotypic and molecular detection of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with burns in Tehran, Iran. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2018;51:610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dallal MMS, Nikkhahi F, Alimohammadi M, Douraghi M, Rajabi Z, Foroushani AR, et al. Phage therapy as an approach to control Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis infection in mice. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2019;52:e20190290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pishnian Z, Haeili M, Feizi A. Prevalence and molecular determinants of colistin resistance among commensal Enterobacteriaceae isolated from poultry in northwest of Iran. Gut Pathog 2019;11:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jafari Z, Harati AA, Haeili M, Kardan-Yamchi J, Jafari S, Jabalameli F, et al. Molecular epidemiology and drug resistance pattern of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Microb Drug Resist 2019;25:336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haeili M, Javani A, Moradi J, Jafari Z, Feizabadi MM, Babaei E. MgrB alterations mediate colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Front Microbiol 2017;8:2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azam M, Gaind R, Yadav G, Sharma A, Upmanyu K, Jain M, et al. Colistin resistance among multiple sequence types of Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with diverse resistance mechanisms: a report from India. Front Microbiol 2021;12:609840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esposito EP, Cervoni M, Bernardo M, Crivaro V, Cuccurullo S, Imperi F, et al. Molecular epidemiology and virulence profiles of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae blood isolates from the hospital agency “Ospedale dei Colli,” Naples, Italy. Front Microbiol 2018;9:1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghafur A, Shankar C, GnanaSoundari P, Venkatesan M, Mani D, Thirunarayanan M, et al. Detection of chromosomal and plasmid-mediated mechanisms of colistin resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from Indian food samples. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2019;16:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malli E, Florou Z, Tsilipounidaki K, Voulgaridi I, Stefos A, Xitsas S, et al. Evaluation of rapid polymyxin NP test to detect colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in a tertiary Greek hospital. J Microbiol Methods 2018;153:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung LM, Cooper VS, Rasko DA, Guo Q, Pacey MP, McElheny CL, et al. Structural modification of LPS in colistin-resistant, KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:3035–3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW, et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1(8):e316–e327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aris P, Robatjazi S, Nikkhahi F, Amin Marashi SM. Molecular mechanisms and prevalence of colistin resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Middle East region: A review over five last years. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2020;22:625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]