Introduction

Medical student assessment during clerkships is largely driven by clinical performance ratings, but many students perceive clinical evaluations to be “unfair.” 1,2 Although more training of evaluators may address this issue, lack of a shared mental model for what defines different levels of performance may contribute to the perception of unfairness.3 Frame-of-reference (FOR) training is an approach to promote a shared mental model by using a “frame of reference” against which raters can compare and evaluate their students. Studies have shown that FOR training allows raters to apply the outlined standards and result in more accurate ratings.4,5 However, FOR training is often resource-intensive, and prior studies have not included training students. The objectives of this study were to develop an online, interactive, frame-of-reference training module to facilitate FOR training, to determine if FOR training for students can improve rating accuracy and enhance understanding of clerkship expectations for clinical performance, and to compare if there are differences between faculty-led, in-person versus remote FOR training.

Methods

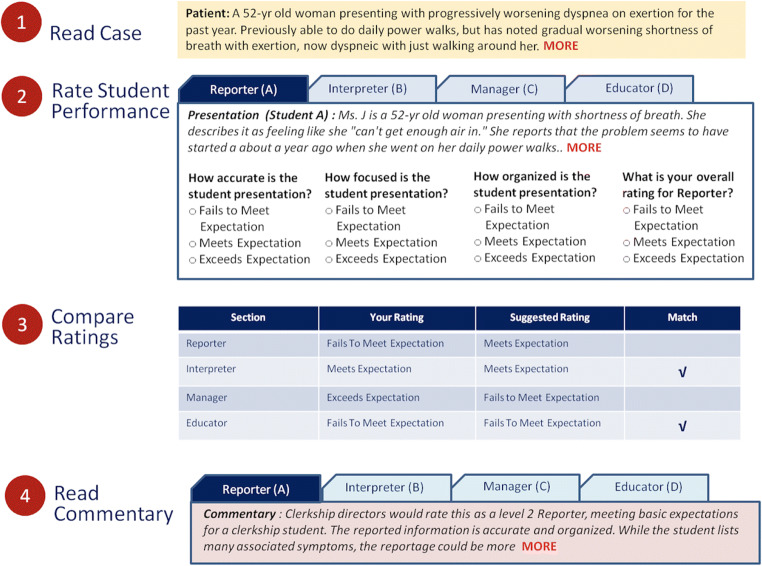

Core faculty in the medicine clerkship developed multiple case presentations that demonstrated different levels of performance in the Reporter, Interpreter, Manager, and Educator (RIME) components of our clerkship evaluation form, adapted from Pangaro’s RIME framework.6 The case presentations were revised in an iterative fashion to reach a consensus in defining each of the case presentations as below, at, or exceeding expectations. Using these presentations, an online, interactive frame-of-reference training tool was developed where students, prior to starting clerkships, rated a set of case presentations, compared their ratings to those determined by core faculty (correct ratings), and received feedback about why a given presentation merits a particular rating (Fig. 1). At the start of the clerkship, students completed another training module with a new set of case presentations, either remotely on their own (odd-numbered clerkship blocks) or in-person with group discussion facilitated by the clerkship director (even-numbered blocks).

Figure 1.

A schematic view of the online training module. The training activity involves ratings 8 different student presentations. Correct ratings and commentary are provided to the user as feedback half way through the activity and again at the end.

We used chi-square (SPSS v26.0. Armonk, NY) to compare proportion of correct ratings on case presentations at baseline versus in-clerkship training and to compare student responses between remote versus in-person training groups to an end-of-clerkship survey asking how well they agree with the statement “The on-line training module gave me a good understanding of clerkship expectations and how students are evaluated” on a 5-point Likert scale. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Results

All rising 3rd year students (N=177) completed baseline training, and 140 students (100% enrolled in blocks 1–6 of medicine clerkship) completed the in-clerkship training. Students enrolled in blocks 7 and 8 were excluded due to COVID-related cancellations/rescheduling of rotations. Overall, the percentage of cases answered correctly at baseline was 64.8% and improved to 74.5% at in-clerkship training (p<0.001). In looking at individual domains of RIME, improvements were seen for all domains except Interpreter (Table 1). The pattern of improvement was not statistically different between remote versus in-person training groups. The majority of students (70.6%) agreed or strongly agreed that the FOR training improved their understanding of clerkship expectations (66.0% of remote versus 75.0% of in-person training groups, p=0.604).

Table 1.

Proportion of Case Presentations Rated Correctly by Students on Frame-of-Reference Training

| Case presentation type | Baseline training N=177 |

Repeat training, total N=140 |

p-value* | Repeat training, remote N=68 |

Repeat training, in-person N=72 |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter | 197/354 cases (55.7%) | 209/309 cases (67.6%) | 0.002 | 114/173 cases (65.9%) | 95/136 cases (69.9%) | 0.46 |

| Interpreter | 260/350 cases (74.3%) | 194/309 cases (62.8%) | 0.001 | 102/173 cases (59%) | 92/136 cases (67.6%) | 0.12 |

| Manager | 236/347 cases (68.0%) | 255/309 cases (82.5%) | <0.001 | 143/173 cases (82.7%) | 112/136 cases (82.4%) | 0.94 |

| Educator | 212/339 cases (62.5%) | 263/309 cases (85.1%) | <0.001 | 151/173 cases (87.3%) | 112/136 cases (82.4%) | 0.23 |

*Based on chi-square test for comparison of correctly rated cases between baseline training and repeat training, total

†Based on chi-square test for comparison of correctly rated cases between repeat training, remote and repeat training, in-person

Discussion

In this study of frame-of-reference training for students, we found a significant increase in proportion of cases rated correctly from baseline to in-clerkship training. The lack of improvement in the Interpreter domain likely reflects the challenges posed by clinical reasoning required for Interpreter, a component of RIME which students are most uncomfortable with during preclinical years, and a skill most heavily emphasized in the medicine clerkship. Repeating the training module at the end of the medicine clerkship may have shown different results. Use of a single-site, clerkship and limited number of cases in the training module are additional limitations. Our finding that student perception regarding usefulness of the training was similar between remote versus in-person training is worth noting since faculty time and effort, common barriers to many educational efforts, in this case did not significantly improve effectiveness of training.

While much of the effort to improve clinical evaluations has focused on rater training, including students in frame-of-reference training may allow a shared mental model for more specific clinical performance expectations. Our findings show that a brief, online, frame-of-reference training tool is feasible and effective.

Author Contributors

None.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: none

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bullock JL, Lai CJ, Lockspeiser T, et al. In Pursuit of Honors: a Multi-Institutional Study of Students’ Perceptions of Clerkship Evaluation and Grading. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S48–S56. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffield KE, Spencer JA. A survey of medical students’ views about the purposes and fairness of assessment. Med Educ. 2002;36(9):879–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jonge LPJWM, Timmerman AA, Govaerts MJB, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on workplace-based performance assessment: towards a better understanding of assessor behaviour. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2017;22(5):1213–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9760-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roch SG, Woehr DJ, Mishra V, Kieszczynska U. Rater training revisited: An updated meta-analytic review of frame-of-reference training. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2012;85(2):370–395. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman LR, Brodsky D, Jones RN, Schwartzstein RM, Atkins KM, Roberts DH. Frame-of-reference training: establishing reliable assessment of teaching effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(3):206–210. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203–1207. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]