Abstract

A class D β-lactamase determinant was isolated from the genome of Legionella (Fluoribacter) gormanii ATCC 33297T. The enzyme, named OXA-29, is quite divergent from other class D β-lactamases, being more similar (33 to 43% amino acid identity) to those of groups III (OXA-1) and IV (OXA-9, OXA-12, OXA-18, and OXA-22) than to other class D enzymes (21 to 24% sequence identity). Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the closer ancestry of OXA-29 with members of the former groups. The OXA-29 enzyme was purified from an Escherichia coli strain overexpressing the gene via a T7-based expression system by a single ion-exchange chromatography step on S-Sepharose. The mature enzyme consists of a 28.5-kDa polypeptide and exhibits an isoelectric pH of >9. Analysis of the kinetic parameters of OXA-29 revealed efficient activity (kcat/Km ratios of >105 M−1 · s−1) for several penam compounds (oxacillin, methicillin, penicillin G, ampicillin, carbenicillin, and piperacillin) and also for cefazolin and nitrocefin. Oxyimino cephalosporins and aztreonam were also hydrolyzed, although less efficiently (kcat/Km ratios of around 103 M−1 · s−1). Carbapenems were neither hydrolyzed nor inhibitory. OXA-29 was inhibited by BRL 42715 (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], 0.44 μM) and by tazobactam (IC50, 3.2 μM), but not by clavulanate. It was also unusually resistant to chloride ions (IC50, >100 mM). Unlike OXA-10, OXA-29 was apparently found as a dimer both in diluted solutions and in the presence of EDTA. Its activity was either unaffected or inhibited by divalent cations. OXA-29 is a new class D β-lactamase that exhibits some unusual properties likely reflecting original structural and mechanistic features.

Class D β-lactamases are a group of structurally related active site serine enzymes that share a common ancestry with the high-molecular-weight class C penicillin-binding proteins (18). Class D β-lactamases usually exhibit a preference for penam substrates, including oxacillin and related compounds (hence their eponyms of oxacillinases or OXA-type β-lactamases), and with few exceptions are poorly inhibited by clavulanic acid, being classified in group 2d of the functional classification of β-lactamases (7, 21). Unlike other β-lactamases, class D enzymes are inhibited by chloride ions and tend to exhibit “burst” kinetics, with initial hydrolysis rates declining more rapidly than can be explained by substrate depletion (16).

Recently the structure of OXA-10 has been solved, providing major insights into the structural and mechanistic features of these enzymes (12, 19, 25). The structural data suggested that the catalytic mechanism of class D β-lactamases is different from that of other serine β-lactamases and also provided some explanation of the mechanism of chloride inhibition typical of these enzymes (12, 19, 25). Another remarkable feature of OXA-10, which could apply to other class D β-lactamases as well, is the tendency to form dimers in the presence of some divalent cations and to exhibit modified kinetic behavior upon dimerization (25).

Currently, some 30 different class D β-lactamases have been described (1, 2, 5, 10, 21, 23, 27, 35), and several groups have been identified within this class on the basis of the degree of structural relatedness among the various members (21, 32). Most known class D β-lactamases are encoded by genes carried on mobile elements, while a minority are encoded by genes apparently resident in some microbial genomes (21). From a clinical standpoint, the relevance of class D β-lactamases is essentially dependent on their occurrence as acquired enzymes in clinical isolates of various gram-negative pathogens, such as pseudomonads, acinetobacters, and enteric bacteria (7, 17, 21). The finding of class D β-lactamases that are active on oxyimino-cephalosporins or carbapenems (1, 2, 5, 10, 21, 27) has further enhanced their medical interest.

In this work we report the characterization of a new class D β-lactamase determinant from Legionella (Fluoribacter) gormanii, the product of which, named OXA-29, is quite divergent from and exhibits some unusual features compared to other class D enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and genetic vectors.

The L. gormanii type strain (ATCC 33297), an isolate from soil, was the donor strain for the blaOXA-29 gene. Escherichia coli DH5α (Gibco-BRL, Bethesda, Md.) was used as host for genetic vectors and recombinant plasmids. E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen Inc., Madison, Wis.) was used as host for overexpression of the blaOXA-29 gene under the control of the T7 promoter. Plasmid pBC-SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used for subcloning procedures.

Recombinant DNA methodology and susceptibility testing.

Basic recombinant DNA procedures were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (31). Construction of the L. gormanii genomic library in the plasmid vector pACYC184 has been described previously (4). In vitro susceptibility testing by disk diffusion was carried out as described previously (14).

DNA sequencing and computer analysis of sequence data.

DNA sequences were determined on both strands by the dideoxy chain termination method as described previously (4). Similarity searches against sequence databases were performed using an updated version of the BLAST program at the BLAST interface of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The multiple sequence alignment was generated with the help of the PILEUP program of the Wisconsin package (version 8.1; Genetics Computer Group Inc., Madison, Wis.) and manually refined considering the information available on the three-dimensional structure of OXA-10 (25). Phylogenetic analysis was carried out as described previously (30).

β-Lactam compounds and other chemicals.

β-Lactam compounds were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) or directly from manufacturing companies. Other chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co.

Purification of the OXA-29 enzyme.

The OXA-29 enzyme was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLBC-5rC) as follows. The strain was grown in 1 liter of brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing chloramphenicol (60 μg/ml) for 20 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) (PB), resuspended in 90 ml of PB, and disrupted by sonication (five times for 30 s each time at 60 W). Cell debris was removed by high-speed centrifugation (105,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C) and the clarified supernatant was loaded onto an S-Sepharose FF column (2.5 by 30 cm; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Milan, Italy) equilibrated with PB. After washing the column with the same buffer, the bound proteins were eluted by a linear (0 to 1 M) NaCl gradient over 100 min at a flow rate of 3 ml/min (preliminary experiments had shown that the oxacillinase activity present in the clarified extract was only partially inhibited at high NaCl concentrations [>0.5 M] and could be completely recovered following dialysis against PB). The fractions showing β-lactamase activity (with oxacillin as the substrate [see below]) and containing a single 28.5-kDa protein band when analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were pooled, dialyzed against PB, and concentrated by ultrafiltration at 0.5 mg/ml. Protein concentrations were determined with a commercial kit (Bio-Rad Richmond, Ca.) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The purified enzyme was stored at −80°C until used.

Protein electrophoretic techniques.

Analytical isoelectric focusing and subsequent zymographic detection of bands of β-lactamase activity were carried out as described previously (30). SDS-PAGE was carried out as described by Laemmli (15), with final acrylamide concentrations of 15 and 5% (wt/vol) for the separating and stacking gels, respectively. After electrophoresis the protein bands were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

N terminus sequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry.

The amino-terminal sequence of the purified OXA-29 protein was determined using a gas-phase sequencer (Procise-492; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) after resuspension of the protein (50 pmol) in a 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid solution and loading of the sample onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). Electrospray mass spectrometry was carried out using VG Bio-Q equipment upgraded with a platform source (Micromass, Altrincham, United Kingdom). The samples (100 pmol) were suspended in 0.05% (vol/vol) formic acid–50% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water and injected in the source of the mass spectrometer using a Harvard syringe pump (Harvard Instruments, South Natick, Mass.) at a flow rate of 6 μl/min. The capillary was held at 2.7 kV, and the cone voltage was set at 40 V. Fifteen scans covering 600 to 1,500 atomic mass units were accumulated during 135 s and processed using the MASSLYNX software provided with the instrument. Horse heart myoglobin was used for calibration.

Determination of free sulfhydryl groups.

Determination of free sulfhydryl groups was carried out by monitoring the absorbance variation at 412 nm following incubation of the purified enzyme (13 μM) with 1 mM 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) in PB at 37°C over a period of 60 min. SDS (0.3% [wt/vol]) was then added and recording was continued for an additional 60 min under the same conditions. The number of free sulfhydryl groups per molecule was calculated from the ratio between the concentration of free sylfhydryl groups (ɛ = 13,600 M−1 cm−1) and that of the protein.

Enzyme assays.

β-Lactamase activity in crude E. coli extracts was assayed in PB at 25°C using 0.1 mM nitrocefin as substrate. Crude extracts were prepared as described previously (4). During purification, β-lactamase activity was assayed in PB at 25°C using 0.5 mM oxacillin as substrate. Kinetic parameters were determined by measuring substrate hydrolysis by the purified enzyme using a lambda 2 spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Rahway, N.J.). The wavelengths and changes in the extinction coefficients used in the spectrophotometric assays were 260 nm and +450 M−1 cm−1 for oxacillin, 260 nm and −100 M−1 cm−1 for methicillin, 260 nm and −7,400 M−1 cm−1 for cefazolin, and as described previously (30) for the other substrates. The steady-state kinetic parameters (Km and kcat) were determined under initial-rate conditions using the Hanes-Woolf plot (34). The Km values lower than 20 μM were measured as Kis using 0.1 mM nitrocefin as reporter substrate, as described previously (30). Enzyme reactions for kinetic measurements were carried out in PB at 25°C in a total volume of 0.75 ml, using an enzyme concentration ranging from 10 to 235 nM. Inhibition by clavulanate, sulbactam, tazobactam, BRL 42715, imipenem, meropenem, and NaCl was assayed after a 5-min preincubation at 25°C with each compound and using 0.1 mM nitrocefin as substrate, an enzyme concentration of 10 nM, and the same experimental conditions as for kinetic measurements. The effect of EDTA and of divalent cations on the OXA-29 activity was investigated after a 20-min preincubation at 25°C with each compound and using 0.1 mM nitrocefin, an enzyme concentration of 10 nM, and the buffer system used by Paetzel et al. (25) for studying the effect of cations on OXA-10 (100 mM Tris-H2SO4 [pH 7.0] containing 0.3 M K2SO4). Inhibition was also assayed with CuSO4 by adding the compound at a 0.5 mM final concentration to an enzyme reaction in progress under otherwise identical experimental conditions. Reactivation by EDTA after exposure to CuSO4 was investigated after incubation of the enzyme-cation mixture with EDTA at a final concentration of 1.5 mM for 20 min at 25°C. Enzyme concentrations were always computed on the basis of an Mr value of 28,500.

Size-exclusion chromatography.

Size-exclusion chromatography experiments were carried out as follows. The purified enzyme was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 100 mM Tris-H2SO4 (pH 7.0) containing 0.3 M K2SO4 or against the same buffer added with 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM CuSO4, or 0.5 mM ZnSO4. After dialysis, the protein concentration was determined as described above. The protein solution at a concentration of 20 nM was loaded on a Superdex 75 column (1 by 30 cm; Pharmacia) equilibrated with the various buffers and eluted in the same buffers at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The column was calibrated using carbonic anhydrase (Mr, 29,000), ovalbumin (Mr, 45,000), and bovine serum albumin (Mr, 66,000). The retention volumes were measured by monitoring the A280 value. The retention volumes of the various standards were not affected by the presence of EDTA or cations in the buffer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ sequence databases and assigned the accession number AJ400619.

RESULTS

Cloning of a class D β-lactamase determinant from the genome of L. gormanii ATCC 33297T.

L. gormanii ATCC 33297T is known to carry a metallo-β-lactamase determinant encoding a class B enzyme, named FEZ-1, that exhibits preferential activity against cephalosporin substrates (4, 11, 20). To screen for the presence of additional β-lactamase determinants, suggested by a comparison of previous results (4, 11), a genomic library of this strain, constructed in the E. coli plasmid vector pACYC184 and transformed into E. coli DH5α, was replica plated on Luria-Bertani medium (31) containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml). Three ampicillin-resistant clones were obtained out of approximately 14,000 screened recombinants. A crude extract of each clone exhibited a nitrocefin-hydrolyzing specific activity higher than that of DH5α(pACYC184). In a disk diffusion test, the three clones exhibited a notable reduction of susceptibility, not only to ampicillin but also to carbenicillin, piperacillin, and cefazolin, compared to E. coli DH5α(pACYC184). No significant reduction of susceptibility was apparent with any of the three clones to cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, and carbapenems. A Southern hybridization analysis of the plasmids carried by the above clones using a blaFEZ-1 probe showed that none of them contained blaFEZ-1-related sequences. Restriction mapping and cross-hybridization experiments revealed that the three clones carried partially overlapping genomic sequences (data not shown). Altogether, the above results suggested that a second β-lactamase determinant, different from blaFEZ-1, had been isolated from the genome of L. gormanii ATCC 33297T. The recombinant plasmid containing the smallest insert (pLB-5BX) (Fig. 1) was selected for further characterization.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the insert of plasmid pLB-5BX and subcloning strategy. Thick lines represent cloned DNA while thin lines represent vector sequences. Production of β-lactamase activity (β-lact.) was assayed on crude extracts as described in Materials and Methods. B, BamHI; C, ClaI; H, HindIII; Sa, SalI; X, XhoI. The location of the blaOXA-29 gene is indicated below the map. The location of the T7 promoter in the plasmid used for overexpression of the blaOXA-29 gene is also indicated. Results of Southern blot hybridization with genomic DNA indicated that one or both of the BamHI sites found at the insert ends are not present in the genomic DNA but were generated after cloning of the Sau3AI genomic fragment into the BamHI site of pACYC184.

A Southern hybridization analysis of the genomic DNA of ATCC 33297T with a probe consisting of the 2.6-kb BamHI insert of pLB-5BX (Fig. 1) confirmed the origin of the cloned fragment from a single chromosomal region of the donor strain. The probe hybridized with the band of undigested chromosomal DNA, with a single 5.2-kb fragment after digestion with BamHI and with two fragments, of 3.1 and 1.4 kb, after digestion with ClaI (data not shown). Subcloning analysis indicated that the β-lactamase determinant was located within a 1.7-kb ClaI-BamHI fragment and apparently interrupted by a SalI site (Fig. 1).

The sequence of the insert of pLBC-5rC (Fig. 1) was determined. An 801-bp open reading frame was identified encoding a polypeptide that in a BLAST search exhibited the highest similarities (BLAST Bit scores of >150) with class D β-lactamases of groups III (OXA-12 [29], AmpS [38], OXA-9 [36], OXA-18 [26], and OXA-22 [23]) and IV (OXA-1 [24], OXA-30 [35]), and OXA-31 [2]) and lower similarities (BLAST Bit scores of <100) with other class D β-lactamases. Results of the subcloning experiments were consistent with the identification of this ORF, named blaOXA-29, as the β-lactamase determinant (Fig. 1). The G+C content of the blaOXA-29 gene is 36.6%, consistent with that reported for the genomes of Legionellaceae (6).

The blaOXA-29 gene encodes a 266-amino-acid polypeptide whose amino-terminal sequence exhibits features typical of bacterial signal peptides targeting protein secretion into the periplasmic space via the general secretory pathway (28). The cleavage site was experimentally determined after the Ala-20 residue (see below). This would yield a mature protein of calculated molecular mass and pI values of 28,541 Da and 9.37, respectively, which are in good agreement with the experimental results obtained with the purified protein (see below).

Structural comparison of OXA-29 with other class D β-lactamases.

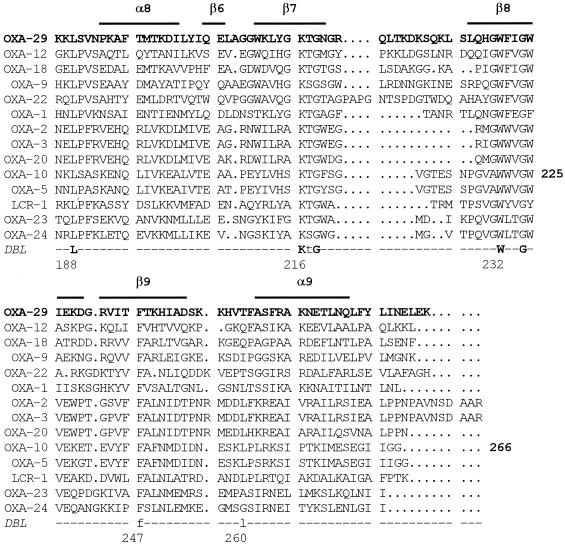

A multiple sequence alignment analysis of the mature OXA-29 protein with representatives of the principal lineages of class D β-lactamases confirmed that OXA-29 is a new class D enzyme quite divergent from other class D β-lactamases which exhibits an overall higher similarity to OXA-12, OXA-18, OXA-9, OXA-22, and OXA-1 than to other class D β-lactamases (Fig. 2 and Table 1). In particular, OXA-29 could be aligned with OXA-12, OXA-18, and OXA-9 without introducing major gaps, while some longer insertions or deletions at the termini or within loops were evident in the alignment with OXA-22, OXA-1, and the other class D β-lactamases (Fig. 2). Interestingly, although a better alignment was observed between OXA-29 and OXA-22 than between OXA-29 and OXA-1, the percent amino acid identity with the latter enzyme was notably higher (41 versus 33%) (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the OXA-29 sequence (in bold) with those of other class D β-lactamases representative of the principal lineages of this enzyme family (only one member of each group, including closely related variants that exhibit >95% amino acid sequence identity between each other, was taken for the comparison). OXA-12, OXA-12 enzyme from Aeromonas jandaei AER 14M (29); OXA-18, OXA-18 enzyme from Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mus (26); OXA-9, OXA-9 enzyme from Klebsiella pneumoniae JHCK1 (36); OXA-22, OXA-22 enzyme from Ralstonia pickettii PIC-1 (23); OXA-1, OXA-1 enzyme from E. coli K10-35 (24); OXA-2, OXA-2 enzyme from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 1a (9); OXA-3, OXA-3 enzyme from P. aeruginosa (32); OXA-20, OXA-20 enzyme from P. aeruginosa Mus (22); OXA-10, OXA-10 enzyme from P. aeruginosa POW151 (13); OXA-5, OXA-5 enzyme from P. aeruginosa 7607 (8); LCR-1, LCR-1 enzyme from P. aeruginosa 2293E (8); OXA-23, OXA-23 enzyme from Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92 (10); OXA-24, OXA-24 enzyme from A. baumannii RYC 52763/97 (5). The previously proposed class D β-lactamase (DBL) consensus and numbering (8) are indicated below the alignment (uppercase and boldletters are the currently recognized invariant residues, and lowercase letters are the others). The positions of the structural elements of OXA-10 (25) are indicated above the alignment. The numbering of OXA-10 is also indicated in bold on the right side of that sequence.

TABLE 1.

Percent amino acid identities between class D β-lactamasesa

| Enzyme | % Amino acid identity between indicated enzymes

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXA-18 | OXA-9 | OXA-22 | OXA-1 | OXA-2 | OXA-3 | OXA-20 | OXA-10 | OXA-5 | LCR-1 | OXA-23 | OXA-24 | OXA-29 | |

| OXA-12 | 44 | 42 | 38 | 35 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 43 |

| OXA-18 | 49 | 42 | 33 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 21 | 43 | |

| OXA-9 | 40 | 32 | 24 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 40 | ||

| OXA-22 | 32 | 23 | 22 | 24 | 21 | 21 | 24 | 22 | 19 | 33 | |||

| OXA-1 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 22 | 23 | 41 | ||||

| OXA-2 | 91 | 78 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 29 | 29 | 24 | |||||

| OXA-3 | 77 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 30 | 29 | 24 | ||||||

| OXA-20 | 37 | 39 | 39 | 30 | 30 | 24 | |||||||

| OXA-10 | 84 | 33 | 36 | 38 | 22 | ||||||||

| OXA-5 | 34 | 36 | 37 | 21 | |||||||||

| LCR-1 | 32 | 31 | 22 | ||||||||||

| OXA-23 | 61 | 22 | |||||||||||

| OXA-24 | 21 | ||||||||||||

All the invariant residues that are common to other class D β-lactamases (Ser-67, Phe-69, Lys-70, Ser-115, Val-117, Gly-142, Trp-154, Leu-159, Leu-178, Lys-205, Gly-207, Trp-221, and Gly-224, in the numbering of OXA-10 [25]) were found to be conserved also in OXA-29 (Fig. 2).

Compared to OXA-10, for which a three-dimensional structure is available (25), OXA-29 differs (i) by lacking the initial amino-terminal β1 strand and α1 helix, (ii) by containing a slightly shorter linker between the β2 and β3 strands and a slightly longer linker between the α3 and α4 helices, (iii) by the presence of a remarkably elongated Ω loop, and (iv) by containing a longer linker between the β7 and β8 strands (Fig. 2). The three active site class D elements of OXA-10 (Ser-67-X-X-Lys-70 [element 1], Ser-115-X-Val-117 [element 2], and Lys-205-Thr-206-Gly-207 [element 3]), as well as the Trp-154 residue that plays a critical role in binding a buried water molecule which is thought to be crucial in the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme (25), are retained in OXA-29. Of the residues that contribute to the hydrophobic character of the OXA-10 active site region (25), three (Trp-102, Val-117, Leu-155) are conserved in OXA-29, while Met-99 is replaced by a different hydrophobic residue (leucine) and Phe-208 and Leu-247 are replaced by polar residues (asparagine and threonine, respectively). Of the residues that in OXA-10 are known to participate in dimerization via hydrophobic interactions in the α8-β6 region (25), Ile-187 is replaced by a different hydrophobic residue (methionine), while Val-193, Leu-186, and Ala-196 are replaced by polar or charged residues (tyrosine, threonine, and glutamate, respectively) in OXA-29. Of the residues that in OXA-10 are known to participate in cation-mediated dimerization (25), Glu-227 is conserved in OXA-29, while Glu-190 is conservatively replaced by an aspartate and His-203 is nonconservatively replaced by a tyrosine (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic relationships of OXA-29 with representatives of the other lineages of class D β-lactamases, analyzed by construction of an unrooted tree, confirmed that OXA-29 belongs in a deep-branching class D lineage that apparently shared a common ancestry with those leading to members of groups III and IV during the early phases of class D β-lactamase evolution (data not shown).

Purification and characterization of the OXA-29 β-lactamase.

Overexpression of the blaOXA-29 gene was obtained by introducing the recombinant plasmid pLBC-5rC, in which the blaOXA-29 gene is located downstream of the T7 promoter flanking the polylinker of pBC-SK (Fig. 1), into the E. coli strain BL21(DE3). The OXA-29 enzyme was purified from a crude lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLBC-5rC) by means of a single step of cation-exchange chromatography on S-Sepharose, with a final yield of approximately 3 mg of purified protein per liter of culture (Table 2). After SDS-PAGE the purified protein appeared as a single band of approximately 28 kDa and was estimated to be >99% pure (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the purification steps of the OXA-29 enzyme produced by E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLBC-5rC)

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg of protein)a | Total activity (U) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 612 | 0.64 | 392 | 100 | 1 |

| S-Sepharose FF eluate | 3.1 | 71 | 220 | 56 | 111 |

One unit of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme hydrolyzing 1 μmol of oxacillin per min under the conditions described in Materials and Methods.

The isoelectric pH of the purified protein was ≥9 (results not shown). The amino-terminal sequence of the protein was determined to be NH2-QSTXFLV. The Mr of the protein, determined by electrospray mass spectrometry, was 28,536 ± 8, in good agreement with the calculated value (28,541).

The presence of free sulfhydryl groups was determined by exposure of the protein to DTNB. Reactivity to DTNB was not detectable under nondenaturing conditions, while upon addition of SDS the presence of one free sulfhydryl group per molecule was detected. These results indicated that, of the three cyteine residues present in OXA-29, two form a disulfide bond while one is free but not readily accessible. Comparison with the OXA-10 structure (25) suggests that the cysteine residues at positions 40 and 59 (in the numbering of OXA-10) are likely to form a disulfide bridge and that the free cysteine residue would be that present within the active site element 2 (Fig. 2).

The OXA-29 enzyme hydrolyzed penicillins (including oxacillin, methicillin, penicillin G, ampicillin, carbenicillin, and piperacillin), cephalosporins (including nitrocefin, cefazolin, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, and ceftazidime), and aztreonam. The highest acylation efficiencies were observed with oxacillin, ampicillin, penicillin G, and nitrocefin (kcat/Km ratios were >6 × 106 M−1 · s−1). With the other penicillins and with cefazolin the efficiencies were approximately 10-fold lower than those observed with oxacillin, while oxyimino cephalosporins and aztreonam behaved as relatively poor substrates (kcat/Km ratios were ≤1 × 103 M−1 · s−1). Carbapenems were not hydrolyzed (Table 3). Burst kinetics were not observed with any of the tested substrates.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters determined with the purified OXA-29 β-lactamase

| Substrate | Km (μM)a | kcat (S−1)a | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxacillin | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 34 ± 3 | 7.7 × 106 |

| Methicillin | 41 ± 4 | 27 ± 2 | 6.6 × 105 |

| Penicillin G | 10 ± 1 | 65 ± 6 | 6.5 × 106 |

| Ampicillin | 16 ± 1 | 107 ± 10 | 6.7 × 106 |

| Carbenicillin | 16 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 8.1 × 105 |

| Piperacillin | 39 ± 3 | 31 ± 3 | 7.9 × 105 |

| Nitrocefin | 96 ± 6 | 1,800 ± 150 | 1.9 × 107 |

| Cefazolin | 30 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 | 3.7 × 105 |

| Cefuroxime | >250 | >0.19 | 7.9 × 102 |

| Cefotaxime | 128 ± 11 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 1.3 × 103 |

| Ceftazidime | >500 | >0.24 | 4.9 × 102 |

| Aztreonam | 210 ± 17 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 1.0 × 103 |

| Imipenem | NHb | NH | NH |

| Meropenem | NH | NH | NH |

Km and kcat values are the means of three different measurements ± standard deviations.

NH, no hydrolysis was detected after 10 min at substrate concentrations up to 0.5 mM and enzyme concentrations up to 235 nM.

OXA-29 was strongly inhibited by BRL 42715 (50% inhibitory concentrations [IC50], 0.44 ± 0.03 μM), was less sensitive to tazobactam (IC50, 3.2 ± 0.3 μM) and to sulbactam (IC50, 48 ± 4 μM), and was resistant to clavulanic acid (IC50, >1 mM). No reduction of activity was detected in the presence of carbapenems (imipenem or meropenem) up to a final concentration of 0.5 mM or in the presence of NaCl up to a final concentration of 100 mM.

The effect of divalent cations on the activity of OXA-29 was assayed under the same experimental conditions utilized by Paetzel et al. (25) to study OXA-10. The activity of OXA-29 was apparently unaffected by EDTA and by some divalent cations, including Ca2+ and Mn2+, and it was variably inhibited by other divalent cations including Mg2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+ (Table 4). Copper was the strongest inhibitor. When added to an ongoing enzyme reaction at a final concentration of 0.5 mM, a progressive reduction of the reaction velocity was observed and inhibition was complete within approximately 40 s. Inhibition by copper ions could be completely relieved by subsequent addition of EDTA to the reaction mixture.

TABLE 4.

Effect of EDTA and various cations on OXA-29 β-lactamase activitya

| Substance (concentration [mM]) | Activity (%) |

|---|---|

| None | 100 |

| EDTA (1) | 116 |

| CaCl2 (0.5) | 91 |

| MgSO4 (0.5) | 76 |

| ZnSO4 (0.5) | 13 |

| MnCl2 (0.5) | 103 |

| CdCl2 (0.5) | 15 |

| CuSO4 (0.5) | <1b |

The activity was determined using 0.1 mM nitrocefin as substrate under the conditions reported in Materials and Methods. Results are the mean values of three measurements. The standard deviations were always lower than 10% of the indicated values.

In this case the activity could be completely recovered after the addition of EDTA (1.5 mM final concentration) to the enzyme-cation mixture.

The Mr value of the purified OXA-29 enzyme, determined by size-exclusion chromatography at a relatively low protein concentration (20 nM), was approximately 55,000, suggesting that OXA-29 is normally found as a dimer. This apparent Mr was not modified in the presence of EDTA (1 mM final concentration) or Zn2+ (0.5 mM final concentration), while in the presence of Cu2+ (0.5 mM final concentration) the protein eluted as a broad peak corresponding to a size range of 25,000 to 55,000, suggesting the presence of an equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric species.

DISCUSSION

The results of this work indicate that, in addition to the FEZ-1 metallo-β-lactamase determinant (4), the genome of the L. gormanii type strain also contains a class D β-lactamase determinant. Although the presence of related sequences was not sought in additional strains of this species, the finding of this determinant in the type strain suggests that it could be found in L. gormanii generally. Moreover, the presence of a close homolog in the genome of Legionella pneumophila (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) supports the view that similar determinants are resident in the genomes of at least some Legionellaceae. The hydrolytic profile of the latter enzyme, named OXA-29, is mostly oriented toward penam compounds, being fairly complementary to that of FEZ-1 which, in turn, prefers cephem compounds and is also active on carbapenems (4, 20). Taken together, therefore, the two Legionella enzymes are able to hydrolyze a very broad repertoire of β-lactam substrates. A similar scenario, with multiple β-lactamases of different classes and of complementary or partially overlapping substrate profiles encoded by the same microbial genome, is not unique but has already been observed in other bacterial pathogens of environmental origin such as Aeromonas spp. (39), Chryseobacterium meningosepticum (3, 30), and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (33, 37).

Structural comparisons and phylogenetic analysis revealed that OXA-29 exhibits a closer relatedness and ancestry with class D β-lactamases of groups III and IV and belongs to a deep-branching lineage that diverged early from a common ancestor during the evolution of that subset of class D enzyme. In particular, OXA-29 seems to be about halfway between groups III and IV and could be assigned to either of them on the basis of the degree of sequence relatedness. OXA-29 and the other enzymes of groups III and IV appear to be quite divergent from other class D β-lactamases, and exhibit some distinctive structural features, including (i) the presence of a longer Ω loop, (ii) the lack of the first β-strand and α-helix found at the amino terminus of other class D β-lactamases (with the exception of OXA-1), and (iii) the presence of a longer linker between the β7 and β8 strands (again with the exception of OXA-1). It would be interesting to understand if and how those differences could be relevant to the mechanistic properties of these enzymes.

In fact, analysis of the functional behavior of OXA-29 revealed some unusual properties compared to other class D β-lactamases. These did not primarily concern the substrate profile, which generally resembles that of most other class D β-lactamases (7, 21), but rather the general kinetic behavior and its dependence on the ionic environment. A first original feature of OXA-29 was represented by the lack of inhibition at chloride concentrations that completely block the activity of other class D β-lactamases. Since in OXA-10 the inhibition by chloride is thought to be due to the displacement of a water molecule of catalytic significance by Cl− (25), the chloride resistance of OXA-29 might be dependent either on a lower affinity for Cl− of that site or on differences in the mechanism of the deacylation step (25). Moreover, OXA-29 did not show a tendency to exhibit burst kinetics and, unlike OXA-10 (25), its activity at relatively low concentrations was not significantly enhanced by the presence of Zn2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+. Actually, the above cations, and mostly Cu2+, proved to be inhibitory to the OXA-29 activity, but EDTA could completely relieve the copper-dependent inhibition. A different response to divalent cations was also observed at the level of quaternary structure: unlike OXA-10 (25), OXA-29 was also found as a dimer at relatively low protein concentrations and in the presence of EDTA, while Cu2+, which was the strongest inhibitor, seemed to exert a destabilizing effect on the dimeric structure. These notable differences suggest that the effect of cations observed for OXA-10, which apparently enhance the enzyme activity by promoting its dimerization (25), is not readily applicable to all other class D β-lactamases.

Altogether, the original features of OXA-29 point to the existence of mechanistic and structural heterogeneity among class D β-lactamases. For this reason, detailed structural and mechanistic studies on OXA-29 are currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper was supported in part by grants from the University of Siena (Piano di Ateneo per la Ricerca, Quota Servizi 1999), from M.U.R.S.T. (PRIN 99), and from the Belgian Program Pôles d'Attraction Interuniversitaire initiated by the Belgian State, Prime Minister's Office, Services Fédéraux des Affaires Economiques, Techniques et Culturelles (PAI P4/03).

REFERENCES

- 1.Afzal-Shah M, Woodford N, Livermore D M. Characterization of OXA-25, OXA-26, and OXA-27 molecular class D β-lactamases associated with carbapenem resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:583–588. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.583-588.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert D, Poirel L, Chevalier J, Leotard S, Pages J M, Nordmann P. Oxacillinase-mediated resistance to cefepime and susceptibility to ceftazidime in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1615–1620. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1615-1620.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellais S, Aubert D, Naas T, Nordmann P. Molecular and biochemical heterogeneity of class B carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases in Chryseobacterium meningosepticum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1878–1886. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1878-1886.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boschi L, Mercuri P S, Riccio M L, Amicosante G, Galleni M, Frère J-M, Rossolini G M. The Legionella (Fluoribacter) gormanii metallo-β-lactamase: a new member of the highly divergent lineage of molecular subclass B3 β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1538–1543. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1538-1543.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bou G, Oliver A, Martìnez-Beltràn J. OXA-24, a novel class D β-lactamase with carbapenemase activity in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1556–1561. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1556-1561.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner D J, Feeley J C, Weaver R E. Family VII. Legionellaceae. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The William & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couture F, Lachapelle J, Levesque R C. Phylogeny of LCR-1 and OXA-5 with class A and class D β-lactamases. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1693–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dale J W, Godwin D, Mossakowska D, Sephenson P, Wall S. Sequence of the OXA-2 β-lactamase: comparison with other penicillin-reactive enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1985;191:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donald H M, Scaife W, Amyes S G B, Young H-K. Sequence analysis of ARI-1, a novel OXA β-lactamase, responsible for imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:196–199. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.196-199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii T, Sato K, Miyata K, Inoue M, Mitsuhashi S. Biochemical properties of β-lactamase produced by Legionella gormanii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:925–926. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.5.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golemi D, Maveyraud L, Vakulenko S, Tranier S, Ishiwata A, Kotra L P, Samama J-P, Mobashery S. The first structural and mechanistic insights for class D β-lactamases: evidence for a novel catalytic process for turnover of β-lactam antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6132–6133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huovinen P, Huovinen S, Jacoby G A. Sequence of PSE-2 beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:134–136. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen J H, Turnidge J D, Washington J A. Antibacterial susceptibility tests: dilution and disk diffusion methods. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 1526–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledent P, Raquet X, Joris B, Van Beeumen J, Frère J-M. A comparative study of class D β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1993;292:555–562. doi: 10.1042/bj2920555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massova I, Mobashery S. Kinship and diversification of bacterial penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1–17. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maveyraud L, Golemi D, Kotra L P, Tranier S, Vakulenko S, Mobashery S, Samama J-P. Insights into class D β-lactamases are revealed by the crystal structure of the OXA-10 enzyme from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Structure. 2000;8:1289–1298. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercuri P S, Bouillenne F, Boschi L, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Amicosante G, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, Frère J-M, Rossolini G M, Galleni M. Biochemical characterization of the FEZ-1 metallo-β-lactamase of Legionella gormanii ATCC 33297T produced in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1254–1262. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1254-1262.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naas T, Nordmann P. OXA-type β-lactamases. Curr Pharm Design. 1999;5:865–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naas T, Sougakoff W, Casetta A, Nordmann P. Molecular characterization of OXA-20, a novel class D β-lactamase, and its integron from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2074–2083. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Kubina M, Casetta A, Naas T. Biochemical-genetic characterization and distribution of OXA-22, a chromosomal and inducible class D β-lactamase from Ralstonia (Pseudomonas) pickettii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2201–2204. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2201-2204.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouellette M, Bissonnette L, Roy P H. Precise insertion of antibiotic resistance determinants into Tn21-like transposons: nucleotide sequence of the OXA-1 β-lactamase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7378–7382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paetzel M, Danel F, de Castro L, Mosimann S C, Page M G P, Strynadka N C J. Crystal structure of the class D β-lactamase OXA-10. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:918–925. doi: 10.1038/79688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippon L N, Naas T, Bouthors A-T, Barakett V, Nordmann P. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2188–2195. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel L, Girlich D, Naas T, Nordmann P. OXA-28, an extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its plasmid- and integron-located gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:447–453. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.447-453.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen B A, Keeney D, Yang Y, Bush K. Cloning and expression of a cloxacillin hydrolyzing enzyme and a cephalosporinase from Aeromonas sobria AER 14M in Escherichia coli: requirement for an E. coli chromosomal mutation for efficient expression of the class D enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2078–2085. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossolini G M, Franceschini N, Lauretti L, Caravelli B, Riccio M L, Galleni M, Frère J-M, Amicosante G. Cloning of a Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) meningosepticum chromosomal gene (blaACME) encoding an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase related to the Bacteroides cephalosporinases and the VEB-1 and PER β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2193–2199. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanschagrin F, Couture F, Levesque R C. Primary structure of OXA-3 and phylogeny of oxacillin-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:887–893. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanschagrin F, Dufresne J, Levesque R C. Molecular heterogeneity of the L-1 metallo-β-lactamase family from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1245–1248. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segel I H. Biochemical calculations. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1976. pp. 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siu L K, Lo J Y C, Yuen K Y, Chau P Y, Ng M H, Ho P L. β-Lactamases in Shigella flexneri isolates from Hong Kong and Shanghai and a novel OXA-1-like β-lactamase, OXA-30. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2034–2038. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2034-2038.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolmaski M E, Crosa J H. Genetic organization of antibiotic resistance genes (aac(6′)-Ib, aadA and oxa-9) in the multiresistance transposon Tn1331. Plasmid. 1993;29:31–40. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh T R, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Sequence analysis and enzyme kinetics of the L2 serine beta-lactamase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1460–1464. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh T R, Hall L, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Sequence analysis of two chromosomally mediated inducible β-lactamases from Aeromonas sobria, strain 163a, one a class D penicillinase, the other an AmpC cephalosporinase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:41–52. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh T R, Stunt R A, Nabi J A, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Distribution and expression of beta-lactamase genes among Aeromonas spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:171–178. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]