Abstract

Background/Objectives

Infections with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may be associated with febrile seizures, but the overall frequency and outcomes are unknown. The objectives of this study are to (1) determine the frequency of pediatric subjects diagnosed with febrile seizures and COVID-19, (2) evaluate patient characteristics, and (3) describe the treatments (medications and need for invasive mechanical ventilation) applied.

Methods

This was a retrospective study utilizing TriNetX electronic health record data. We included subjects ranging from 0 to 5 years of age with a diagnosis of febrile seizures (R56.00, R56.01) and COVID-19 (U07.1). We extracted the following data: age, race, ethnicity, diagnostic codes, medications, laboratory results, and procedures.

Results

During this study period, 8854 pediatric subjects aged 0-5 years were diagnosed with COVID-19 among 34 health care organizations and 44 (0.5%) were also diagnosed with febrile seizures (simple, 30 [68.2%]; complex, 14 [31.8%]). The median age was 1.5 years (1, 2), there were no reported epilepsy diagnoses, and a proportion required hospitalization (11; 25.0%) and critical care services (4; 9.1%).

Conclusions

COVID-19 infections in children can be associated with febrile seizures. In our study, 0.5% of COVID-19 subjects were diagnosed with febrile seizures and approximately 9% of subjects were reported to require critical care services. Febrile seizures, although serious, are not a commonly diagnosed neurologic manifestation of COVID-19.

Keywords: febrile seizures, COVID-19, respiratory viruses, coronavirus, neurologic symptoms of SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Febrile seizures are a common neurologic disorder in children. It is a neurologic event associated with a fever that occurs in a child <5 years without evidence of a central nervous system infection. In West Europe and the United States, approximately 2% to 5% of children will experience a febrile seizure. 1 Generally, the outcomes in these children are favorable. There is a risk of recurrence in approximately one-third of children, but no direct neurocognitive long-term effects. 1 Febrile seizures in a child can also be an emotionally traumatic experience for families. 2

The etiology of febrile seizures is unknown, but it is most likely multifactorial, including but not limited to rate of temperature elevation, viral infections, certain vaccinations, familial genetic syndromes and dispositions, and certain exposures in utero. 2 Viral infections, especially those associated with high fevers, have been shown to increase the neuronal excitability and lower the seizure threshold, especially in the developing central nervous system. 3 The viruses most correlated with febrile seizures include human herpesvirus 6, influenza, adenovirus, parainfluenza, and varicella. Other frequent infections associated with febrile seizures are middle ear infections, upper and lower airway infections (such as tonsillitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia), tooth infections, and gastroenteritis (especially those caused by rotavirus). 4

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been the most prevalent virus during the ongoing coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Coronaviruses are a group of related zoonotic viruses that are characterized as enveloped positive-stranded RNA viruses and known to have an association with the central nervous system. 5 Once the SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the cell in the airways through the angiotensin-converting enzyme, an excessive immune reaction occurs in the host, which leads to a cytokine storm. Activated leukocytes release interleukin-6 (IL-6) as well as other cytokines (including tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-17, IL-8, and IL-1β), which acts on many cells and tissues and results in an acute systemic inflammatory syndrome characterized by fever and multiple organ dysfunction. 6 In some cases, especially in the setting of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), life-threatening neurologic involvement may occur. 7 ,8 Although life-threatening neurologic involvement (ie, stroke, cerebral edema, etc) should be evaluated closely, the hyperinflammatory response triggered by SARS-Co-V-2 combined with the increased neuronal excitability in a developing central nervous system may put children at higher risk for non–life-threatening neurologic events such as febrile seizures. Currently, the frequency, disposition, and treatment requirements specific to febrile seizures and SARS-CoV-2 are unknown and have not been evaluated extensively to our knowledge. 7 Understanding the association between them may inform clinical practice.

The objective of the present study is to evaluate the frequency of febrile seizures in children with SARS-CoV-2, evaluate patient characteristics, and describe the treatments applied.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective study using the TriNetX electronic health record data of pediatric patients between 0 and 5 years of age with febrile seizures (R56.00, R56.01) and COVID-19 infection (U07.1) according to the diagnostic codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. TriNetX is a global-federated research network that provides access to an electronic health record data (ie, diagnoses, procedures, laboratory values) retrieval system from participating health care organizations predominately in the United States. For this present study, TriNetX provided a deidentified data set of electronic medical records (diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory values, genomic information) from 44 patients from health care organizations in the United States. The data are deidentified based on standards defined in section §164.514(a) of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. The process by which data sets are deidentified is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Protected health information or personal data is made available to the users of the platform. No protected health information is received by the user. As such, use of the TriNetX database has an institutional review board waiver.

Data Collection

On April 17, 2021, we analyzed the electronic health record data of 44 pediatric subjects who were reported to have a diagnosis of febrile seizures, a concurrent COVID-19 infection, and no previous history of seizures (ie, epilepsy, seizures, etc). Using diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), we included those for febrile seizures (“R56.00” [ICD-10-CM: “Simple Febrile Seizure”], R56.01 [ICD-10-CM: “Complex Febrile Convulsions”] and associated ICD-9 codes) and the U07.1 code for COVID-19 infection. After the query, we collected and evaluated the following data based on 2 time frames: (1) on the reported day of febrile convulsion and COVID-19 diagnosis (age, sex, race, ethnicity, temperature [maximum value reported], laboratory results, nonfebrile convulsion and non–COVID-19 diagnostic codes, and mortality), and (2) 3 days before and after the reported day of febrile convulsion and COVID-19 diagnosis (medications and procedures). The subject population included encounters in the ambulatory, emergency, and inpatient setting. Because of database limitations, radiologic reports (including neuroimaging) were not available for review. For the purposes of this study, we assumed that the day the diagnostic code was entered for billing was the same as the day the diagnosis was made. The diagnostic, medication, and procedure codes this study focused on are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. To gain current understanding of the reported frequency of febrile seizures in general as well as COVID-19 infections in pediatric patients within the confines of the database, on April 19, 2021, we used the browser-based, real-time analytical features of TriNetX to (1) determine the number of subjects diagnosed with febrile seizures (COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 subjects) and (2) number of subjects diagnosed with COVID-19 from March 1, 2020, to April 19, 2021.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics using median and interquartile range or proportions were reported for clinical and demographic characteristics of the pediatric patients.

Results

Database Cohort Overview

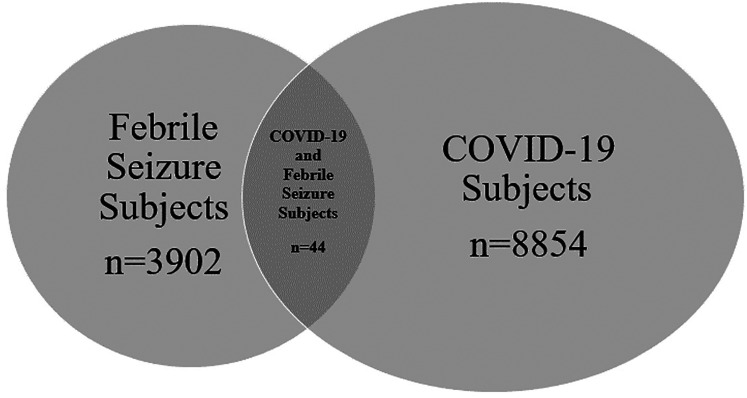

On April 19, 2021, a total of 34 health care organizations reported that 8854 pediatric subjects aged 0-5 years were diagnosed with COVID-19. Thirty-six health care organizations reported that 3902 pediatric subjects aged 0-5 years were diagnosed with febrile seizures. Among these subjects, 44 (0.5%) were diagnosed with febrile seizures and COVID-19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram illustrating the frequency of where subjects were diagnosed with COVID-19, Febrile Seizure, and both.

Patient Characteristics

The majority of patients with febrile seizures were reported to be simple (30; 68.2%) and had no reported epileptic comorbidities (ie, previous history of epilepsy or seizures). Three patients had status epilepticus (6.8%). The subjects’ ages (median [25th, 75th percentile]) averaged to 1.5 years (1, 2), and there were no reported deaths. Diagnostic codes reported 14 subjects (31.8%) had at least 1 additional potential fever-producing infectious disease among the following: enterovirus (1; 2.3%), otitis media (4; 9.1%), pneumonia (1; 2.3%), unspecified viral infection (7; 15.9%), and urinary tract infection (3; 6.8%). The review of laboratory results indicated that no other viruses were reported. Twelve subjects were reported to have 1 additional disease and 2 subjects had 2 additional diseases (urinary tract infection and an unspecified viral infection; enterovirus and an unspecified viral infection) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 44).a

| Characteristic | Febrile Convulsions and COVID-19 (U07.1) Diagnosed Pediatric Subjects |

|---|---|

| Age, y median (25th, 75th %ile) | 1.5 (1, 2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 22 (50) |

| Female | 22 (50) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2.3) |

| Asian | 2 (4.5) |

| Black or African American | 6 (13.6) |

| White | 12 (27.3) |

| Unknown | 23 (52.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 13 (29.5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 24 (54.5) |

| Unknown | 7 (15.9) |

| Number of deaths | 0 (0.0) |

| Type of febrile convulsion | |

| Simple | 30 (68.2) |

| Complex | 14 (31.8) |

| Maximum temperature, °C, median (25th, 75th %ile) b | 39 (38.0,39.4) |

| Encounter type c | |

| Ambulatory | 2 (4.5) |

| Emergency | 15 (34.1) |

| Inpatient | 6 (13.6) |

| Unknown | 29 (65.9) |

| Presence of selected non-neurologic categories at time of febrile convulsion d | |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 1 (2.3) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 6 (13.6) |

| Mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders | 2 (4.5) |

| Sepsis | 3 (6.8) |

| Status epilepticus | 3 (6.8) |

| Specific reported viral testing and presence | |

| Adenovirus | 0 (0.0) |

| Herpes simplex virus | 0 (0.0) |

| Human coronavirus (non–COVID-19) | 0 (0.0) |

| Human metapneumovirus | 0 (0.0) |

| Parainfluenza | 0 (0.0) |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 0 (0.0) |

| Rhinovirus/enterovirus | 0 (0.0) |

| Other selected potential fever-producing infectious diseases reported via diagnostic codes at time of febrile convulsion d | |

| Enterovirus | 1 (2.3) |

| Otitis media | 4 (9.1) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (2.3) |

| Unspecified viral | 7 (15.9) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (6.8) |

Unless otherwise noted, values are n (%).

Temperature available for 11 unique subjects.

Seven subjects had more than 1 encounter listed. Two subjects did not have an encounter reported on day of febrile seizure and COVID-19 diagnosis.

See Supplementary Table 1 for diagnosis details.

COVID-19 Laboratory Characteristics

Laboratory evaluation occurred in 8 subjects (18.2%). The majority of the laboratory results available were unremarkable, with the exception of 3 subjects (6.8%) who had elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Further evaluation of these subjects revealed that the subjects were reported to have simple and complex febrile seizures but not status epilepticus (Table 2).

Table 2.

Available COVID-19–Associated Average Laboratory Values.

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | d-Dimer, ng/mL | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, mm/h | Ferritin, ng/mL | International Normalized Ratio | Prothrombin Time, s | Partial Thromboplastin Time, s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference ranges | <1 | ≤ 0.54 | 0-15 | 30-400 | 0.9-1.1 | 12.0-14.2 | 23-35 |

| Simple febrile convulsion | |||||||

| Subject 1 | 4.47 a | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Subject 2 | 0.5 | – | 5 | – | – | – | – |

| Subject 3 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Complex febrile convulsion | |||||||

| Subject 4 | 1.34 | – | 6 | 27.3 | 1.3 | 15 | 35 |

| Subject 5 b , c | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Both | |||||||

| Subject 6 | 33.5 a | 0.4 | 18 a | – | 1.1 | 12.4 | 31.2 |

| Subject 7 | 8.4 a | – | 41 a | – | – | – | – |

| Subject 8 b | 0.3 | – | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| Median values (25th, 75th %ile) | 5.2 (1.1, 8.1) | 0.4 | 6 (5, 18) | 27.3 | 1.2 (1.15, 1.25) | 13.7 (13.05, 14.35) | 33.1 (32.15, 34.05) |

Elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate).

Status epilepticus.

Critical care services; mechanical ventilation.

Patient Disposition and Therapies

Of the febrile seizure subjects, 26 (59.1%) received emergency department services, 11 (25.0%) required hospitalization, 4 (9.1%) received critical care services, and 1 (2.3%) required invasive mechanical ventilation. Two ambulatory (4.5%), 15 emergency (34.1%), 6 inpatient (13.6%), and 29 unknown (65.9%) visit encounters were reported. Five (11.4%) were administered antiseizure medications, 13 (29.5%) required antiinfectives for systemic use, and 11 (25.0%) received benzodiazepines (Table 3). Three subjects (6.8%) were reported to have sepsis, and 3 (6.8%) were diagnosed with status epilepticus. No inotropic or vasoactive support was reported for the patients with sepsis (Table 1).

Table 3.

Medical Care Required in COVID-19–Positive Patients with Febrile Seizures.

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of medical reported | |

| Emergency department services | 26 (59.1) |

| Hospitalization | 11 (25.0) |

| Critical care services | 4 (9.1) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (2.3) |

| Medications administered | |

| Antiseizure | 5 (11.4) |

| Antiinfectives for systemic use | 13 (29.5) |

| Benzodiazepines | 11 (25.0) |

| Vasoactive infusions | 0 (0.0) |

Discussion

We sought to examine the frequency, clinical factors, and outcomes associated with COVID-19–related febrile seizures in the pediatric population. Our main findings showed that in pediatric COVID-19 patients, 0.5% were diagnosed with febrile seizures, a majority did not have a documented coinfection, and approximately 9% were reported to require critical care services. These findings may indicate that febrile seizures are not a commonly diagnosed neurologic manifestation of COVID-19 infection.

There are numerous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although medical literature has been dominated with respiratory symptoms and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), there are several neurologic complications of infection in the pediatric population that range from common to rare. 7 These complications include headaches, altered mental status, encephalopathy, meningitis, coma, demyelinating disorders, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral neuropathy, and other autoimmune encephalopathies. 9 The pathogenesis of these clinical manifestations is not completely understood but is hypothesized to involve 3 broad categories: direct viral injury to neural cells, vascular endothelial injury, and inflammatory and autoimmune injury. 9

A recent study demonstrated that life-threatening COVID-19–related neurologic conditions such as severe encephalopathy, cerebral edema, stroke, and Guillain-Barre syndrome infrequently occur and are associated with more extreme inflammation. 7 It is more common for children to present with less neurologic involvement in comparison to their adult counterparts, 7 but it is unknown if the care provided in these cases is out of proportion to what is typically seen in non–COVID-19 related settings. Our study, therefore, focused on febrile seizures.

The true incidence of febrile seizures in COVID-19 patients is difficult to assess because of the multiple potential causes previously discussed. It is also difficult to determine if the patients’ febrile seizures were secondary to COVID-19 or another virus, as many patients were co-infected with other viruses. 10 In addition, the admission rate for febrile seizures during the pandemic is conflicting; in one study, it was found that admissions for febrile seizures increased 3-fold during the pandemic as opposed to the previous year. 11 However, in another study, the number of emergency department visits for febrile seizures was significantly less during the pandemic than in prior years because of strict mask-wearing and social distancing habits. 12 In children with COVID-19, potential causes of seizures could be acute infections associated with fever, encephalitis, or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and therefore the diagnosis of febrile seizure should made with caution. Coronaviruses are known to be neuroinvasive 13 and have the capability to cause a cytokine storm, which results in neuroexcitability. 14 It has also been suggested that children with COVID-19 may have hypoxia, metabolic derangements, organ failure, or cerebral damage, all of which can contribute to a lowered seizure threshold. 15 Given how severe COVID-19 infections can be in children, it is important for providers to consider these etiologies when a child presents with febrile seizures or status epilepticus so that treatment can be initiated as soon as possible.

Our study evaluated febrile seizures that were diagnosed in COVID-19 pediatric subjects, which is the largest to date to our knowledge. At the time of this study, only a small proportion of COVID-19 pediatric subjects were diagnosed with febrile seizures, with the simple type being the most common. There are several reasons why this may be the case; it is possible that febrile seizures could be limited to children with severe illness, such as hypoxia or circulatory system issues that require hospitalizations. Although children are vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, a smaller proportion become ill compared with their adult counterparts. 10 There may also be no association with infection with SARS-CoV-2 and febrile seizures.

In the subjects who developed febrile seizures associated with COVID-19, only 25% required hospitalization when seen in the emergency department and even fewer required critical care services. These findings indicate that although COVID-19 may potentially trigger febrile seizures, they may not be as severe and, therefore, do not require intensive intervention (including critical care and hospitalization), similar to other viruses. Because of heightened anxiety from the public standpoint, care may have been sought sooner, which limited the medical burden.

This study had several limitations. This was a retrospective study using an electronic health record database retrieval system that was limited to health care organizations that currently provide data only in the United States but the distribution of the institutions is unclear, which may represent a population bias. Because this is a retrospective study using billing codes, measurement error, misclassification, and selection bias may be present. We were also only able to query for subjects when clinicians entered the diagnostic code for both febrile seizures and COVID-19. It is possible that some subjects were diagnosed with these conditions without them being coded within the electronic health record. TriNetX currently does not provide the precise date of birth (only the year of birth). Thus, we were unable to determine the ages of subjects <1 year. Because of database limitations, it was not possible to review all clinical documentation and data. Resultantly, we were unable to confirm if the febrile seizure diagnoses were made behaviorally or electrographically. We were also unable to determine the most likely cause for febrile seizures in approximately one-third of subjects who had a COVID-19 diagnosis and an alternate infectious etiology reported. It is possible that the subject that received the COVID-19 diagnostic code may have been asymptomatic from the infection and may not have been the reason for the encounter. Our study also did not report if the COVID-19 illness received laboratory confirmation.

Conclusions

COVID-19 infections in children can be associated with febrile seizures. In this study, 0.5% of COVID-19 subjects were diagnosed with febrile seizures and approximately 9% were reported to require critical care services. Febrile seizures may be a less severe neurologic manifestation of COVID-19.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: KC drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as written. CK and KC conceptualized and designed the study and carried out the initial analyses. JB, GDC, and NJT reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. CK collected and organized the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as written.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the NCATS Award, (grant number TR002014).

Ethical Approval: Because no protected health information is received by the user from the TriNetX database, we were provided a waiver from Penn State Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) to perform this study.

ORCID iDs: Katsiah Cadet https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5763-8537

Conrad Krawiec https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7902-2568

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Leung AK, Hon KL, Leung TN. Febrile seizures: an overview. Drugs Context . 2018;7:212536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laino D, Mencaroni E, Esposito S. Management of pediatric febrile seizures. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2018;15:2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DK, Sadler KP, Benedum M. Febrile seizures: risks, evaluation, and prognosis. Am Fam Physician . 2019;99(7):445‐450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han JY, Han SB. Febrile seizures and respiratory viruses determined by multiplex polymerase chain reaction test and clinical diagnosis. Children . 2020;7(11):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgello S. Coronavirus and the central nervous system. J Neurovirol . 2020;26(4):459‐473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tezer H, Demirdag TB. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in children. Turk J Med Sci . 2020;50(SI-1):592‐603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaRovere KL, Riggs BJ, Poussaint TY, et al. Neurologic involvement in children and adolescents hospitalized in the United States for COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome. JAMA Neurol . 2021;78(5):536‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darif D, Hammi I, Kihel A, El Idrissi Saik I, Guessous F, Akarid K. The pro-inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 pathogenesis: what goes wrong? Microb Pathog . 2021;153:104799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JE, Asfour A, Sewell TB, et al. Neurological issues in children with COVID-19. Neurosci Lett . 2020;743:135567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christy A. COVID-19: a review for the pediatric neurologist. J Child Neurol . 2020;35(13):934‐939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smarrazzo A, Mariani R, Valentini F, et al. Three-fold increase in admissions for paediatric febrile seizures during COVID-19 pandemic could indicate alternative virus symptoms. Acta Paediatr . 2020;110(3):939‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu TGA, Leung WCY, Zhang Q, et al. Changes in pediatric seizure-related emergency department attendances during COVID-19 – A territory-wide observational study. J Formos Med Assoc . 2020;120:1647‐1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeed A, Shorafa E. Status epilepticus as a first presentation of COVID-19 infection in a 3 years old boy; case report and review the literature. IDCases . 2020;22:e00942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chegondi M, Kothari H, Chacham S, Badheka A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) associated with febrile status epilepticus in a child. Cureus . 2020;8:e9840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asadi-Pooya AA. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure . 2020;79:49‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]