Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) studies in cognitively-normal (CN) older adults aged ≥ 65 suggest depression is associated with molecular biomarkers (imaging and cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]). This study used linear mixed models (covariance pattern model) to assess whether baseline CSF biomarkers (Aβ42/Aβ40, t-Tau/Aβ42, p-Tau/Aβ42) predicted changes in non-depressed mood states in CN older adults (N=248), with an average of three follow-up years. Participants with higher levels of CSF biomarkers developed more anger, anxiety, and fatigue over time compared to those with more normal levels. Non-depressed mood states in preclinical AD may be a prodrome for neuropsychiatric symptoms in symptomatic AD.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal Fluid, Alzheimer disease, Biomarkers, Older adults, Anger, Anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is often accompanied by depression, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and/or mild behavioral impairment (MBI) in later stages [1–3]. Conversely, depressive symptoms and a depression diagnosis have independently been associated as a prodrome and increased risk factor for both all-cause dementia, and AD specifically [4, 5]. Depression has been identified as a modifiable risk factor for reducing dementia prevalence [6]. In a similar vein, older adults (age 65 and older) who developed NPS (e.g., nighttime behaviors, irritability) experienced a faster change progression to symptomatic AD [7, 8]. Given the complex interactions and difficulty disentangling causality, emerging studies using molecular biomarkers have begun assessing the associations between underlying pathophysiology and early changes in mood [9].

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of amyloid imaging using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) suggest that more abnormal levels of amyloid are associated with depressive symptoms [10–12]. One study investigated and found that PET-tau (not amyloid imaging) was associated with a greater risk of depression diagnosis [13]. In AD, depression as a mood disorder has many distinguishing characteristics that may impact the results, including symptoms vs. diagnosis, active vs. remote, late-life onset vs. lifelong depression, and antidepressant use. Yet, there are limited studies that investigate whether mood states beyond depression are associated with molecular AD biomarkers. A prior study examining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and PET-amyloid biomarkers found that older adults with more change in confusion, anxiety, in addition to depression and NPS over one-year had more elevated levels of CSF and PET biomarkers [9]. However, it is unclear if changes in the non-depressed mood states are sustained over time given the limited follow-up interval. This study builds upon our past research to examine associations between non-depressed, non-behavioral mood states assessed longitudinally and CSF biomarkers in a cognitively-normal sample of older adults.

METHODS

Sample

Participants were enrolled in studies conducted at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. Cognitive normality was defined by a 0 on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR®) [14]. Participants completed an annual clinical and neurological exam, demographics, mood, a health history, and neuropsychological assessments. Biomarker testing (CSF) was obtained every two to three years. Participants were included if they had a CDR® of 0 at baseline assessment and did not progress upon subsequent follow-up. Additionally, CSF data within two years of the baseline mood was used. Mood follow-up data was used until March 1, 2020 to exclude any potential confounding effects of the pandemic on mood. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University in Saint Louis, and all participants provided signed informed consent.

CSF

Following an overnight fast, a trained neurologist used a 22-gauge Sprotte spinal needle to collect 20–30 mL of CSF via standard lumbar puncture into a polypropylene tube at 8:00 A.M. as previously described [15–17]. CSF analytes including amyloid-beta40 (Aβ40), amyloid-beta42 (Aβ42) total tau (t-Tau), and phosphorylated tau181 (p-Tau181) were measured using an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Lumipulse G1200, Fujirebio). CSF biomarker ratios (Aβ42/Aβ40, t-Tau/Aβ42, p-Tau/Aβ42) were used to demarcate preclinical AD given their robustness, sensitivity, and specificity in predicting progression from cognitive-normality to symptomatic AD [17–20]. CSF amyloid cutoffs have high concordance with amyloid PET [21]. Participants were classified as preclinical AD positive if Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio ≤ 0.0673, t-Tau/Aβ42 ratio ≥ 0.488, and p-Tau/Aβ42 ≥ 0.0649 based on established cut-offs [22].

Mood States

The Profile of Mood States—Short Form (POMS-SF) is a self-report, 30-item assessment of six mood states (positive and negative) and provides a total mood disturbance (TMD) score [23]. The six subscales detect presence and severity of anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion (range 30–80). Higher scores on the vigor subscale indicates positive mood while the remaining subscales indicate more negative mood. The TMD score is summation of anxiety, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion subscales, minus the vigor subscale. TMD scale ranges from −20 to 100, where higher scores indicate greater mood disturbance.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized key demographics variables. Longitudinal analyses assumed a linear relationship between POMS subscales and CSF biomarkers within a two-year window of the index date/baseline POMS measurement. A covariance pattern model (linear mixed model) was used to predict mean POMS subscales based on CSF biomarkers. CSF biomarkers were dichotomized using aforementioned cutoffs to reflect negative (without preclinical AD) and positive (with preclinical AD) biomarker values. This model assumed a common variance-covariance correlation structure among the repeatedly measured POMS subscales over time from the same participant. Appropriate correlation matrix was selected based on model fit statistic Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Analyses adjusted for age, gender, and education. Least squares means of POMS subscales for CSF groups were predicted from the covariance pattern model. Regression diagnostics such as residual plots were used to check the assumptions of the linear mixed models. Parallel analyses were conducted substituting the POMS and subscales with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPIQ) and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) using the same biomarker models and demographic adjustments. All the statistical analyses were two-tailed at a significance level of 0.05 and performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participants were on average older, more educated with at least a bachelors’ level of education, has a similar gender distribution, and were a majority of non-Hispanic white (Table 1). There were no impairments in cognitive functioning as reflected by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and only nine percent had a depression diagnosis at baseline assessment. This ongoing study included data from seven years of follow-up POMS data (mean: 3.1 years; range 1–7 years). Approximately one third of the sample had at least one copy of the Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele. Across the three biomarker ratios: Aβ42/Aβ40 (38.3%), t-Tau/Aβ42 (33.9%), p-Tau/Aβ42 (31.9%), roughly a third of the sample were classified as having preclinical AD. On average, the baseline scores on the POMS score centered around the nadir for the five negative moods states suggesting little symptoms and higher on the vigor subscale indicating optimal energy.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics (N=248)*

| Age (years) | 72.78±4.80 | |

| Education (years) | 16.33±2.45 | |

| Women, N (%) | 127 (51.21%) | |

| Race, Caucasian, N (%) | 220 (88.71%) | |

| APOE4, N | 82 (33.47%) | |

| MMSE (out of 30) | 29.28±1.00 | |

| Depression, N (%) | 23 (9.27%) | |

| GDS (out of 15) | 0.69±1.76 | |

| NPIQ (out of 36) | 0.92±1.36 | |

| Follow-up time (years) | 3.12±2.31 | |

| POMS | ||

| TMD | −4.74±8.61 | |

| Tension/Anxiety | 32.83±3.87 | |

| Depression | 32.52±2.29 | |

| Anger | 36.49±2.11 | |

| Vigor | 58.91±9.74 | |

| Fatigue | 32.36±4.48 | |

| Confusion | 38.08±3.78 | |

| Biomarker status (%) | + | − |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 | 95 (38.31%) | 153 (61.69%) |

| t-Tau/Aβ42 | 84 (33.87%) | 164 (66.13%) |

| p-Tau/Aβ42 | 79 (31.85%) | 169 (68.15%) |

Abbreviations: APOE4 = Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; POMS = Profile of Mood States; TMD = Total Mood Disturbance; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; NPIQ = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire

Mean ± Standard Deviation or count (percentage)

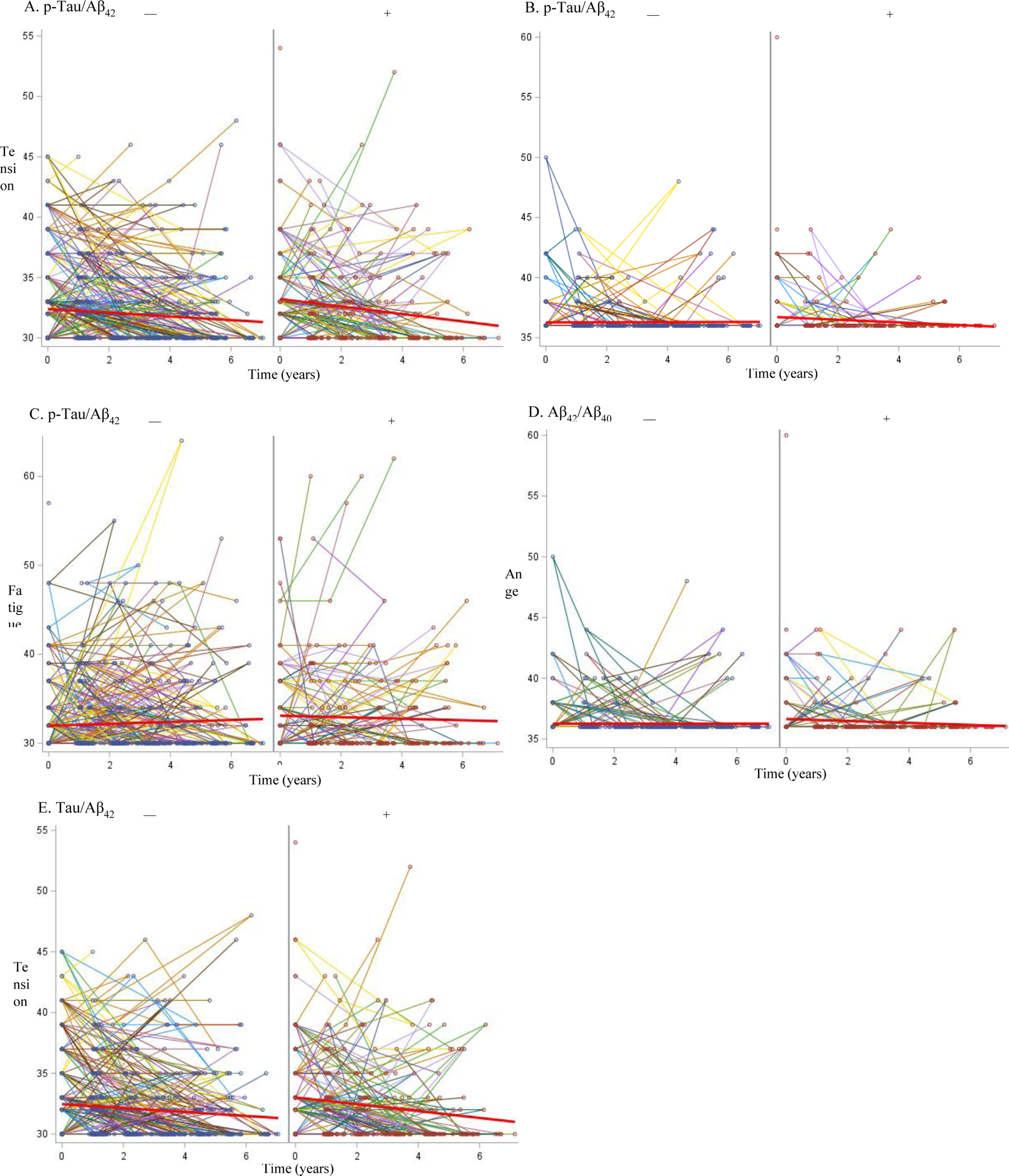

In the longitudinal analyses using the covariance pattern models, three of the subscales of the POMS revealed statistically significant differences between older adults with and without preclinical AD (Table 2; Figure 1). In the anger subscale, participants who were classified as preclinical AD by CSF p-Tau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40 had slightly higher scores compared to those with more normal biomarker levels. Based on p-Tau/Aβ42, older adults with more abnormal levels had higher scores on the tension/anxiety and fatigue subscale, respectively. There were some marginally significant results between the tension/anxiety subscale and Aβ42/Aβ40 (p=0.062) and t-Tau/Aβ42 (p=0.051). Similarly, the fatigue subscale was marginally significant with t-Tau/Aβ42 (p=0.063). There were no significant group differences between the CSF biomarkers on the POMS depression subscale or the TMD. We re-ran the models substituting biomarker group with APOE4 status (+/−) and did not find any group differences with APOE4 across the six mood states or TMD. Analyses conducted with biomarker models(p-Tau/Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40, Tau/Aβ42) and the NPIQ and GDS, independently were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Group means of mood subscales across CSF ratio biomarkers

| POMS | p-Tau/Aβ42 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | p | |||

|

| |||||

| LSM | 95% CI | LSM | 95% CI | ||

| TMD | −4.06 | (−5.80, −2.33) | −5.58 | (−6.77, −4.39) | 0.1598 |

| Anxiety | 33.09 | (32.39, 33.79) | 31.97 | (31.49, 32.45) | 0.0107 |

| Depression | 32.94 | (32.48, 33.41) | 32.46 | (32.14, 32.78) | 0.0950 |

| Anger | 36.67 | (36.39, 36.97) | 36.25 | (36.06, 36.45) | 0.0171 |

| Vigor | 59.78 | (57.94, 61.61) | 58.75 | (57.50, 60.00) | 0.3670 |

| Fatigue | 33.21 | (32.31, 34.09) | 32.08 | (31.47, 32.69) | 0.0426 |

| Confusion | 38.41 | (37.74, 39.09) | 37.71 | (37.25, 38.17) | 0.0916 |

| GDS | 0.999 | (0.785, 1.121) | 1.023 | (0.710, 1.336) | 0.9025 |

| NPIQ | 0.770 | (0.573, 0.966) | 0.852 | (0.562, 1.143) | 0.6448 |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 | |||||

| + | − | p | |||

| LSM | 95% CI | LSM | 95% CI | ||

| TMD | −4.57 | (−6.16, −2.98) | −5.42 | (−6.68, −4.17) | 0.4121 |

| Anxiety | 32.81 | (32.17, 33.46) | 32.03 | (31.52, 32.54) | 0.0627 |

| Depression | 32.79 | (32.36, 33.22) | 32.51 | (32.17, 32.84) | 0.3080 |

| Anger | 36.64 | (36.38, 36.90) | 36.23 | (36.03, 36.44) | 0.0158 |

| Vigor | 59.72 | (58.04, 61.40) | 58.68 | (57.36, 60.00) | 0.3419 |

| Fatigue | 32.79 | (31.97, 33.561 | 32.23 | (31.58, 32.87) | 0.2669 |

| Confusion | 38.21 | (37.59, 38.83) | 37.76 | (37.27, 38.25) | 0.2639 |

| GDS | 1.005 | (0.778, 1.231) | 1.010 | (0.725, 1.296) | 0.9749 |

| NPIQ | 0.777 | (0.570, 0.985) | 0.826 | (0.561, 1.091) | 0.7793 |

| t-Tau/Aβ42 | |||||

| + | − | p | |||

| LSM | 95% CI | LSM | 95% CI | ||

| TMD | −4.06 | (−5.73, −2.38) | −5.64 | (−6.85, −4.43) | 0.1325 |

| Anxiety | 32.88 | (32.20, 33.56) | 32.04 | (31.55, 32.53) | 0.0507 |

| Depression | 32.96 | (32.51, 33.41) | 32.44 | (32.11, 32.76) | 0.0663 |

| Anger | 36.58 | (36.31, 36.86) | 36.29 | (36.09, 36.49) | 0.0930 |

| Vigor | 59.21 | (57.44, 60.97) | 59.01 | (57.73, 60.29) | 0.8593 |

| Fatigue | 33.10 | (32.24, 33.95) | 32.09 | (31.47, 32.71) | 0.0637 |

| Confusion | 38.29 | (37.64, 38.94) | 37.75 | (37.28, 38.22) | 0.1891 |

| GDS | 1.006 | (0.789, 1.225) | 1.007 | (0.789, 1.309) | 0.9966 |

| NPIQ | 0.786 | (0.585, 0.986) | 0.815 | (0.537, 1.093) | 0.8692 |

Abbreviations: POMS = Profile of Mood States; LSM = Least Squares Means; TMD = Total Mood Disturbance; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; NPIQ = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire

Bold = <.05; Italics = marginally significant; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval;

Figure 1. Spaghetti plots for preclinical AD biomarkers and POMS subscales.

Spaghetti plots show the changes in POMS mood subscales for tension/anxiety, anger, and fatigue for Aβ42/Aβ40, t-Tau/Aβ42, p-Tau/Aβ42, with preclinical AD − and + groups to the left and right, respectively. Individual lines represent longitudinal data for a single participant. POMS = Profile of Mood States.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the association between mood states, NPS, and biomarkers, in addition to their changes can provide valuable insight into the trajectory of AD. In this longitudinal study with seven years of follow-up data in cognitively-normal older adults, participants with higher levels of CSF biomarkers developed more anxiety, fatigue, and anger over time compared to those with more normal biomarker levels. There were no statistically significant differences in depression mood state, overall mood disturbances, the NPIQ or GDS between both groups.

Anger was consistently higher across CSF p-Tau/Aβ42 and Aβ42/Aβ40 biomarker groups with more elevated levels. In a study published three decades ago, anger was found to be more prevalent in patients with probable AD and associated with increased cognitive loss as measured by the MMSE, however, depression was not associated with cognitive changes [24]. A recent systematic review found only a handful of biomarker studies examining associations between agitation and aggression which identified positive correlations between CSF Aβ42, p-Tau, and t-Tau [25]. The cross-sectional nature of the small number of biomarker studies was a key limitation identified by the authors. Our longitudinal study followed a cognitively-normal cohort in their natural trajectory of mood changes and found that greater amyloid and tau pathology predicted more change in anger. One potential explanation may be that increased anger in the preclinical stage of AD may be a prodrome for agitation and aggression in NPS or MBI as a premonitory stage [3], when a person progresses to symptomatic AD.

A higher score on the tension/anxiety subscale on the POMS was associated with preclinical AD based on the p-Tau/Aβ42 and Tau/Aβ42 biomarkers (Aβ42/Aβ40 was marginal; p=0.06). Prior studies examining anxiety and AD have found inconsistent results given the shared symptomology with depression [26–28]. A study using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort found that anxiety symptoms in participants with amnestic mild cognitive impairment predicted progression to symptomatic AD, independent of depression [29]. Anxiety was assessed using a single item (including severity rating) on the NPIQ and changes in structural volumetric MRI biomarkers (e.g. intracranial, hippocampal, amygdala) was included in the models with the ADNI cohort. A recent study using the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) cohort [11] found that greater cerebral amyloid (via imaging) was associated with higher anxious-depressive scores based on the GDS symptoms in a cognitively-normal sample followed up to five years. The results from our study extend the findings from the ADNI and HABS cohorts by parceling out depression, using a cognitively-normal cohort, and with a longer follow-up period. Finally, greater fatigue was associated with higher levels of p-Tau/Aβ42 and was marginally associated with t-Tau/Aβ42 (p=0.06). Fatigue, a self-report of tiredness resulting from mental or physical exertion and increased vulnerability to stressors, increases with biological age and can have a negative impact on overall health and well-being [30]. A recent study of Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial cohort found chronic fatigue was associated with greater white matter hyperintensities in a cognitive normal cohort. However, there are limited AD studies examining the relationship between fatigue and amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration biomarkers.

The extant literature examined mood, largely depression and preclinical AD and consistently finds a moderate association with depression symptoms and diagnosis with imaging biomarkers (amyloid and tau tracers) [10, 12, 13]. A key difference between prior research and this study is the use of the POMS survey rather than the GDS or the NPIQ and preclinical AD based on CSF biomarkers. In our prior study [9], we examined differences in the POMS and CSF biomarkers with one year of follow-up data. We found a group difference between t-Tau/Aβ42 but not p-Tau/Aβ42 (Aβ42/Aβ40 was not available at the time). In this study, while t-Tau/Aβ42 did not reach statistical significance, it was marginal (p=0.06) providing consistent results with our prior work but also elucidating new relationships with non-depressed mood states and AD biomarkers.

MBI is conceptualized as the late-life onset of behaviors (low motivation, affect dysregulation, impulse dyscontrol, social inappropriateness, abnormal thought content), which increase the conversion risk from mild cognitive impairment to dementia and may presage transition from cognitive-normality to preclinical stage[31, 32]. MBI is also associated with biomarkers— PET amyloid and plasma neurofilament light, a marker of axonal damage signifying neurodegeneration[33, 34]. Future studies could examine the associations between MBI (behavior), mood states, and AD biomarkers. Cognitive reserve may also impact emergence of negative mood states and moderate the relationship with conversion to prodromal AD and should be examined to assess mediating or moderating roles [35].

There are some limitations despite the longitudinal follow-up period and modest sample size with biomarkers. Obtaining CSF biomarkers is specialized, costly, burdensome, and not widely available. The slightly skewed means on the POMS TMD and subscales may reflect the overall high physical and mental health of the participants in this cohort. This was also reflected in the low prevalence of depression in the sample. Pharmacological therapy including specific medication classes (e.g., antidepressants) can influence the presence and magnitude of behavior and mood states. We did not have data on current medication available to examine and adjust in our analyses. Our sample included a large proportion of non-Hispanic whites, who were well educated, most lacking significant physical disabilities, psychiatric, or neurologic conditions/diagnosis, which may not be representative of the general population. As a result, findings may not be easily generalizable to the larger population.

In sum, the findings from this study of mood states suggest that longitudinal changes in anger, tension/anxiety, and fatigue were associated with baseline preclinical AD biomarkers. These changes in non-depressed mood states may be a prodrome of future NPS or indicative of MBI as an older adult progresses to symptomatic AD. Assessment of various mood states in the preclinical and symptomatic stages of AD may provide more information for clinical diagnostics and to understand the trajectory on how emotive and cognitive changes co-occur to impact function.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) grants R01AG056466 (CMR), R01AG068183 (GMB/CMR), R01AG067428 (GMB), R01AG074302 (GMB). This work was also supported by the BrightFocus Foundation A2021142S (GMB). The authors thank the participants, investigators/staff of the Knight ADRC Clinical, Biomarker, and Genetics Cores.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement

Ganesh M. Babulal reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Ling Chen reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Jason M. Doherty reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Samantha A. Murphy reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Ann M. Johnson reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Catherine M. Roe reports no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Baker L, Galik E, Kopunek S, Steinberg M, Warren A (1997) Major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 9, 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Scaricamazza E, Colonna I, Sancesario GM, Assogna F, Orfei MD, Franchini F, Sancesario G, Mercuri NB, Liguori C (2019) Neuropsychiatric symptoms differently affect mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients: a retrospective observational study. Neurol Sci 40, 1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, Sultzer D, Brodaty H, Smith G, Agüera-Ortiz L, Sweet R, Miller D, Lyketsos CG (2016) Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 12, 195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gallagher D, Kiss A, Lanctot K, Herrmann N (2018) Depression and Risk of Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Longitudinal Analysis to Determine Predictors of Increased Risk among Older Adults with Depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Fournier A, Abell J, Ebmeier K, Kivimäki M, Sabia S (2017) Trajectories of depressive symptoms before diagnosis of dementia: a 28-year follow-up study. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 712–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J (2017) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 390, 2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Masters MC, Morris JC, Roe CM (2015) “Noncognitive” symptoms of early Alzheimer disease A longitudinal analysis. Neurology 84, 617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Creese B, Griffiths A, Brooker H, Corbett A, Aarsland D, Ballard C, Ismail Z (2020) Profile of mild behavioral impairment and factor structure of the mild behavioral impairment checklist in cognitively normal older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 32, 705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Babulal GM, Ghoshal N, Head D, Vernon EK, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Morris JC, Roe CM (2016) Mood Changes in Cognitively Normal Older Adults are Linked to Alzheimer Disease Biomarker Levels. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 24, 1095–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Donovan NJ, Hsu DC, Dagley AS, Schultz AP, Amariglio RE, Mormino EC, Okereke OI, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Marshall GA (2015) Depressive symptoms and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively normal older adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 46, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Donovan NJ, Locascio JJ, Marshall GA, Gatchel J, Hanseeuw BJ, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Harvard Aging Brain S (2018) Longitudinal association of amyloid beta and anxious-depressive symptoms in cognitively normal older adults. Am J Psychiatry 175, 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gatchel JR, Rabin JS, Buckley RF, Locascio JJ, Quiroz YT, Yang H-S, Vannini P, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, Properzi M (2019) Longitudinal association of depression symptoms with cognition and cortical amyloid among community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Network Open 2, e198964–e198964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Babulal GM, Roe CM, Stout SH, Rajasekar G, Wisch JK, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Ances BM (2020) Depression is associated with tau and not amyloid positron emission tomography in cognitively normal adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 74, 1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, LaRossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA (2006) Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in humans. Ann Neurol 59, 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Li Y, Gordon BA, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Xiong C (2019) High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology 93, e1647–e1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schindler SE, Gray JD, Gordon BA, Xiong C, Batrla-Utermann R, Quan M, Wahl S, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM, Morris JC (2018) Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers measured by Elecsys assays compared to amyloid imaging. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14, 1460–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fagan AM, Mintun MM, Shah AR, Aldea P, Roe CM, Mach RH, Marcus D, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2009) Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau181 increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 1, 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2007) Cerebrospinal fluid tau/β-amyloid42 ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol 64, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fagan AM, Younkin LH, Morris JC, Fryer JD, Cole TG, Younkin SG, Holtzman DM (2000) Differences in the Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio associated with cerebrospinal fluid lipoproteins as a function of apolipoprotein E genotype. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 48, 201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Volluz KE, Schindler SE, Henson RL, Xiong C, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Fagan AM ALZ. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Volluz KE, Schindler SE, Henson RL, Xiong C, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Fagan AM (2021) Correspondence of CSF biomarkers measured by Lumipulse assays with amyloid PET. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 17, e051085. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL (1995) Short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychol Assess 7, 80. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cooper JK, Mungas D, Weiler PG (1990) Relation of cognitive status and abnormal behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 38, 867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ruthirakuhan M, Lanctôt KL, Di Scipio M, Ahmed M, Herrmann N (2018) Biomarkers of agitation and aggression in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14, 1344–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Devier DJ, Pelton GH, Tabert MH, Liu X, Cuasay K, Eisenstadt R, Marder K, Stern Y, Devanand DP (2009) The impact of anxiety on conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24, 1335–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ramakers I, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Kester A, Jolles J, Verhey FRJ (2010) Affective symptoms as predictors of Alzheimer’s disease in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a 10-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 40, 1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gulpers B, Ramakers I, Hamel R, Köhler S, Voshaar RO, Verhey F (2016) Anxiety as a predictor for cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 24, 823–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mah L, Binns MA, Steffens DC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2015) Anxiety symptoms in amnestic mild cognitive impairment are associated with medial temporal atrophy and predict conversion to Alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 23, 466–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Avlund K (2010) Fatigue in older adults: an early indicator of the aging process? Aging Clin Exp Res 22, 100–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mortby ME, Ismail Z, Anstey KJ (2018) Prevalence estimates of mild behavioral impairment in a population-based sample of pre-dementia states and cognitively healthy older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 30, 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Creese B, Brooker H, Ismail Z, Wesnes KA, Hampshire A, Khan Z, Megalogeni M, Corbett A, Aarsland D, Ballard C (2019) Mild behavioral impairment as a marker of cognitive decline in cognitively normal older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 27, 823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lussier FZ, Pascoal TA, Chamoun M, Therriault J, Tissot C, Savard M, Kang MS, Mathotaarachchi S, Benedet AL, Parsons M (2020) Mild behavioral impairment is associated with β-amyloid but not tau or neurodegeneration in cognitively intact elderly individuals. Alzheimer’s & dementia 16, 192–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Naude JP, Gill S, Hu S, McGirr A, Forkert ND, Monchi O, Stys PK, Smith EE, Ismail Z, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2020) Plasma neurofilament light: a marker of neurodegeneration in mild behavioral impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease 76, 1017–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Opdebeeck C, Matthews FE, Wu Y-T, Woods RT, Brayne C, Clare L (2018) Cognitive reserve as a moderator of the negative association between mood and cognition: evidence from a population-representative cohort. Psychol Med 48, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]