Abstract

Objective

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), characterized by cardiomyopathy with the absence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and valvular heart disease in patients with diabetes, significantly increases the risk of heart failure. Galectin-3 (Gal-3) has been shown to regulate cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, but its role in DCM remains unclear. This study aimed to determine whether Gal-3 inhibition attenuates DCM and NF-κB p65 activation.

Methods

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) was established by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of streptozotocin for 5 consecutive days in mice. Myocardial injury markers, such as creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK-BM) and lactate dehydrogenase, were detected using ELISA. We used non-invasive transthoracic echocardiography to examine cardiac structure and function. Histological staining was used to explore myocardial morphology and fibrosis. Profibrotic markers and inflammatory cytokines were detected by ELISA and real-time PCR in vivo. The terminal deoxyribonucleotide transferasemediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) and immunofluorescence assays were conducted to examine myocardial apoptosis and oxidative stress. Inflammatory cytokines induced by high glucose (HG) were also found in RAW264.7 macrophages. The underlying molecular mechanisms were determined using immunofluorescence and Western blotting analyses.

Results

The Gal-3 knockdown was observed to ameliorate myocardial apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines release, macrophage infiltration, and fibrosis, thus, decreasing cardiac dysfunction in DCM mice. In addition, the silence of Gal-3 could suppress macrophage infiltration and inflammatory cytokine release induced by HG. Finally, a Gal-3/NF-κB p65 regulatory network was clarified in the pathogenesis of DCM.

Conclusion

The Gal-3 may promote myocardial apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in vivo and in vitro by the mechanism of reduction of NF-κB p65 activation.

Keywords: Galectin-3, diabetic cardiomyopathy, inflammation, macrophage, fibrosis

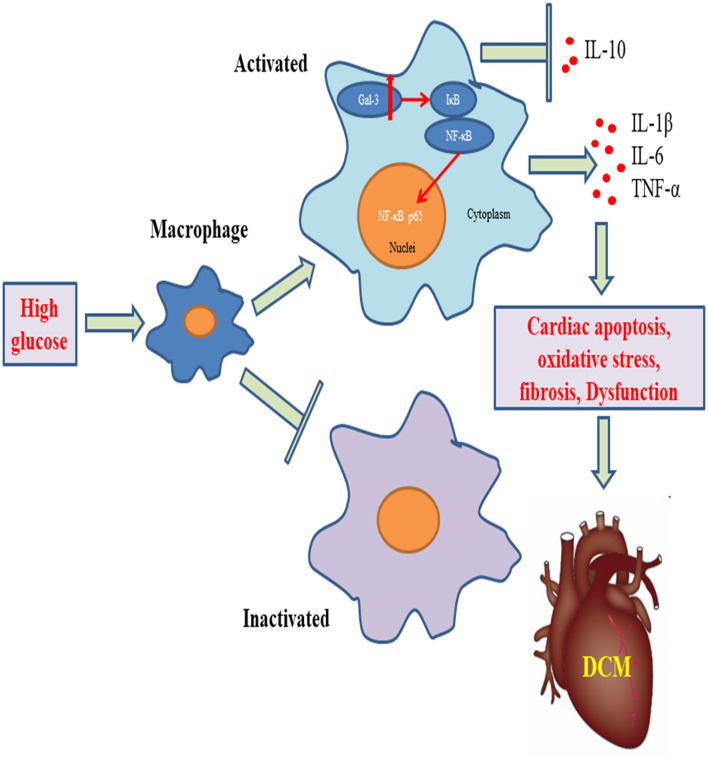

Graphical Abstract

Gal-3 triggers myocardial apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines release, macrophage infiltration, and fibrosis, leading to cardiac dysfunction in DCM mice.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a global epidemic and is expected to affect over 693 million people worldwide by 2045 (1). Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) was defined as a pathophysiological condition, in which heart failure (HF) occurred in the absence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and valvular heart disease (2). Multiple pathophysiological factors in diabetes promote the development of cardiomyopathy from the early stages of diastolic cardiac fibrosis and stiffness/relaxation dysfunction to a later stage of systolic HF (3). The HF results in worsened clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus (4). Many commonly used antihyperglycemic therapies have successfully reduced hyperglycemia in diabetes, but these drugs have not reduced the high occurrence of HF (5). In addition, the protective effects of novel hypoglycemic drugs, such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (6, 7) and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs (8), on HF are independent of the hypoglycemic effect. Furthermore, dapagliflozin has been shown to reduce the risk of HF worsening, regardless of diabetes status (9). As a result, factors other than glycemia may contribute to the risk of HF in patients with diabetes.

Many pathophysiological mechanisms, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, aberrant insulin signaling, autophagy, myocardial metabolism, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and lipotoxicity, might be amenable to pharmacological therapy to decrease the risk of cardiac dysfunction in DCM. The role of maladaptive inflammation cytokines in the pathogenesis of DCM and HF has been established. Inflammatory cell infiltration, such as macrophages, may play a role in myocardial fibroblast collagen expression (10). Infiltrating macrophages and associated inflammatory cytokines can be implicated in diabetes-induced cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction (1). The activation of nuclear factor k-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) plays an important role in triggering cytokine expression and proinflammatory response (11). Furthermore, pro-inflammatory factors, such as NLRP3 inflammasome and the Toll-like receptor-4, promote DCM by the modulation of NF-kB (12, 13). Increased circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukins (IL) 1 and 6, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and monocyte chemotactic protein 1, also drive cardiac remodeling and fibrosis, and final diastolic dysfunction (14, 15). As a result, reducing inflammation macrophage infiltration is a promising strategy for DCM treatment.

Galectin-3 (Gal-3), which is a 30-kDa lectin secreted mainly by macrophages, contains a carbohydrate-recognition binding domain that binds to β-galactoside (16). Gal-3 plays an important disease-exacerbating role in autoimmune/inflammatory and malignant diseases (17–19). Gal-3 suppression attenuates many fibrotic diseases (20). In particular, Gal-3 plays a key role in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Cardiovascular fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and ventricular dysfunction are all caused by recombinant Gal-3 (21). In a long-term transverse aortic constriction mouse model, inhibiting Gal-3 slows the progression of cardiac remodeling (22). Gal3 can also link inflammation to decreased insulin sensitivity (23). However, the role of Gal-3 in the progression of DCM and high glucose (HG)-induced macrophage activation remains unknown. In this study, we investigated whether Gal-3 contributes to the development of DCM in vivo and molecular mechanisms in vitro.

Methods

Animal Preparations and Experiments

All the animal procedures were approved by the Wenzhou Medical University Animal Policy and Welfare Committee and conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines. Male C57BL/6 mice (18–22 g) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Zhejiang Province (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). All animals were housed at a constant room temperature with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and had free access to diet and water. The mice, aged 8 weeks old, received streptozotocin (STZ, 50 mg/kg) or vehicle (citrate buffer) by i.p. injection for 5 consecutive days. One week later, their fasting blood glucose levels were measured with a glucometer, and mice with glucose levels greater than 16.7 mmol/l were considered diabetic. The diabetic mice were randomly divided into four groups: a control group and diabetic mice received 2.5 × 1010 viral genomes of adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV-9) incorporating Gal-3-short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (AAV9-Gal-3) or an equal amount of AAV-9 incorporating scrambled-shRNA (AAV9-NC) via the tail vein injection, respectively. All mice were fed for another 16 weeks, and their blood glucose levels were measured weekly. Before detection, mouse hearts were isolated at 16 weeks and stored at −80°C or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

ELISA Analyses

The blood of mice was collected by retrobulbar bleeding and was centrifuged for 2,000 rpm for 20 min. The mice serum was stored at −80°C for further analyses. The concentrations of serum creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured using commercial ELISA kits (Cloud-Clone, China). Heart issues or culture supernatants of RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were collected. The concentrations of IL-10, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β1 were also detected using commercial ELISA kits (Beyotime and DAKEWE, China).

Echocardiography Analyses

The cardiac systolic and diastolic functions were determined using non-invasive transthoracic echocardiography in anesthetized mice (VEVO3100, Fujifilm VisualSonics). Left ventricular end-systolic diameter and end-diastolic diameter (LVESD, LVEDD), ejection fraction (EF), and fractional shortening (FS) were measured.

Histological and Fibrotic Analyses

The paraffin-embedded cardiac tissues of mice were continuously sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Masson staining were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The morphology and fibrosis of heart tissue were examined under a light microscope (Nikon) at a magnification of 400 ×.

TUNEL Staining

TUNEL staining was performed to detect cell apoptosis in the heart. After dewaxing and rehydrating, heart tissue sections (4 μm thick) were washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized with Proteinase K (0.02 μg/μl). These sections were incubated with a TUNEL staining solution based on the manufacturer's recommendation. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was evaluated by a fluorescence microscope.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Trizol was used to lyse heart tissues after they were harvested. The Primescript RT reagent kit was used for both reverse transcription and quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Takara, Japan). The light cycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Switzerland) was used for qPCR analyses. The primer sequences of types I and III collagen (COL1A2 and COL3A1) were generated by our laboratory and are as follows: COL1A2, forward 5′-CACCCCAGCGAAGAACTCAT-3′, reverse 5′-TCTCCTCATCCAGGTACGCA-3′; COL3A1A1, forward 5′-GAGGAATGGGTGGCTATCCG-3′, reverse 5′-TCGTCCAGGTCTTCCTGACT-3′; and GAPDH, forward 5′-ATGGGTGTGAACCACGAGAA-3′, reverse 5′-ATGAGCCCTTCCACAATGCC-3′. The amount of each gene was detected and normalized to the amount of GAPDH.

Immunofluorescence Analyses

Heart issues or RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min and incubated with blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Specimens were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (CD68, Abcam, 1:200; Gal-3, Abcam, 1:200; eNOS, Abcam, 1:200) and 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibody. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI and the signals were measured using a confocal laser microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Western Blotting

Heart issues or RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were lysed with a Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. For nuclear and cytoplasmic protein analyses, the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) was used. Total protein concentrations were determined with the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime). Protein samples (50 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis by 8–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, and blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% tween and 5% non-fat dry milk. Primary antibody (Gal-3, Abcam, 1:5,000; p-IκB, Santa Cruz, 1:500; IκB, Proteintech, 1:1,000; p-NF-κB p65, AFFINITY, 1:500; p50, Proteintech, 1:200; b-actin Atagenix, 1:3,000; GAPDH, Proteintech, 1:5,000) incubations were performed at 4°C overnight, and secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoreactive bands were visualized using Enhanced Luminol Reagent and Oxidizing Reagent. Densitometric analyses were conducted using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical Analyses

The experimental data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The differences between groups were analyzed with Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Pro5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). All p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Gal-3 Inhibition Decreased Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Injury

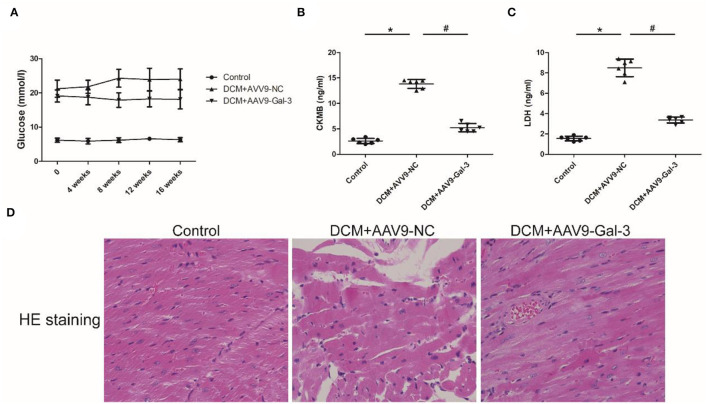

Streptozotocin (STZ) caused an increase in the blood glucose level in the DCM group, and the blood glucose level was maintained during the experiment interval (Figure 1A). However, the blood glucose level was significantly decreased in the DCM+AAV9-Gal-3 group. Furthermore, the ELISA assay revealed that myocardial injury markers (CK-MB and LDH) were upregulated in the DCM group, whereas Gal-3 inhibition reduced the increase (Figures 1B,C). The myocardial structure was examined by HE-staining. Diabetes induced histological abnormalities, whereas treatment with AAV9-Gal-3 markedly reversed these abnormalities (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Gal-3 inhibition decreased diabetes-induced cardiac injury (A) blood glucose level was measured during 16 weeks after STZ injection. (B,C) ELISA analysis of heart CK-MB and LDH expression at 16 weeks after STZ injection. (D) HE staining of heart tissue at 16 weeks after STZ injection. Magnification, 200 ×. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; # P<0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

Gal-3 Inhibition Reversed Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction

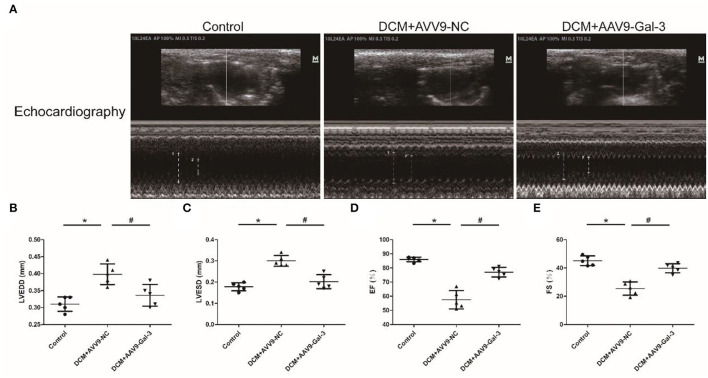

Cardiac structure and function were examined by echocardiographic measurement (Figure 2A). Diabetic mice had cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction, as evidenced by increased LVEDD and LVESD (Figures 2B,C), as well as decreased EF% and FS% (Figures 2D,E). Improved cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction was also observed by Gal-3 inhibition.

Figure 2.

Gal-3 inhibition reversed diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction (A–E) echocardiographic measurement of cardiac structure and function. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; # P < 0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

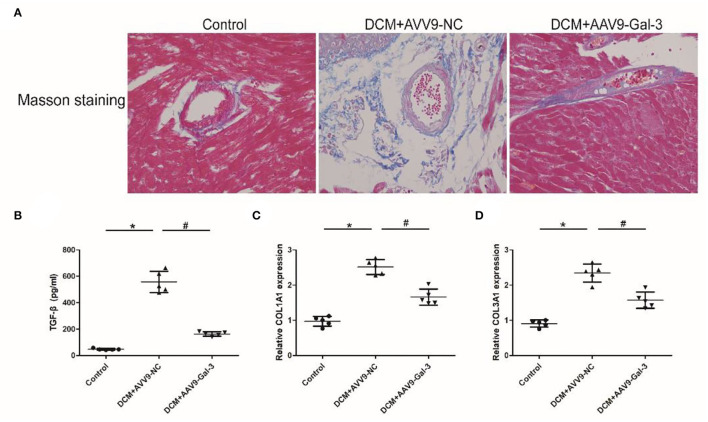

Gal-3 Inhibition Attenuated Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis

Masson staining showed Gal-3 inhibition ameliorated myocardial fibrosis in diabetic mice (Figure 3A). The ELISA and real-time PCR analyses revealed a significant increase in profibrotic makers, including TGF-β (Figure 3B) and COL1A2 and COL3A1 (Figures 3C,D) expressions in diabetic hearts.

Figure 3.

Gal-3 inhibition attenuated diabetes-induced cardiac fibrosis (A) Masson staining of heart tissue at 16 weeks after STZ injection. Magnification, 200 ×. (B) ELISA analysis of heart TGF-β expression. (C,D) Real-time PCR analysis of COL1A2 and COL3A1 mRAN level. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; # P < 0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

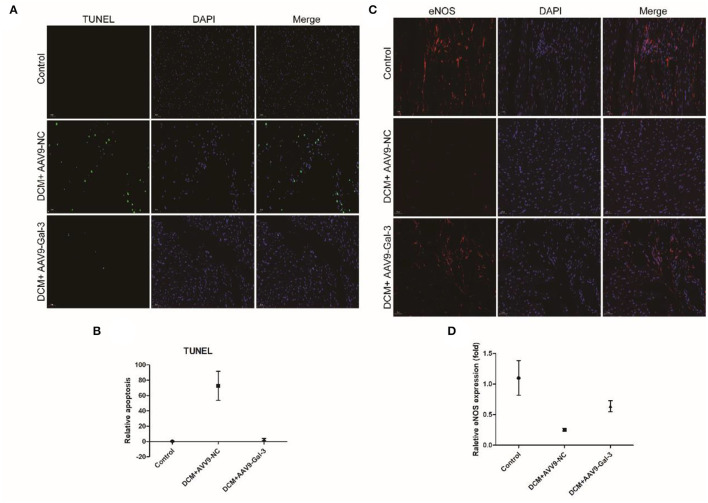

Gal-3 Inhibition Decreased Diabetes-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in the Heart

The TUNEL staining showed diabetes-induced cardiac apoptosis, while Gal-3 inhibition reduced apoptosis (Figures 4A,B). Diabetes-induced downregulations of antioxidant marker-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) were reversed by Gal-3 inhibition (Figures 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Gal-3 inhibition reduced diabetes-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress (A,B) TUNEL and (C,D) immunofluorescence staining of eNOS in heart tissue at 16 weeks after STZ injection. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

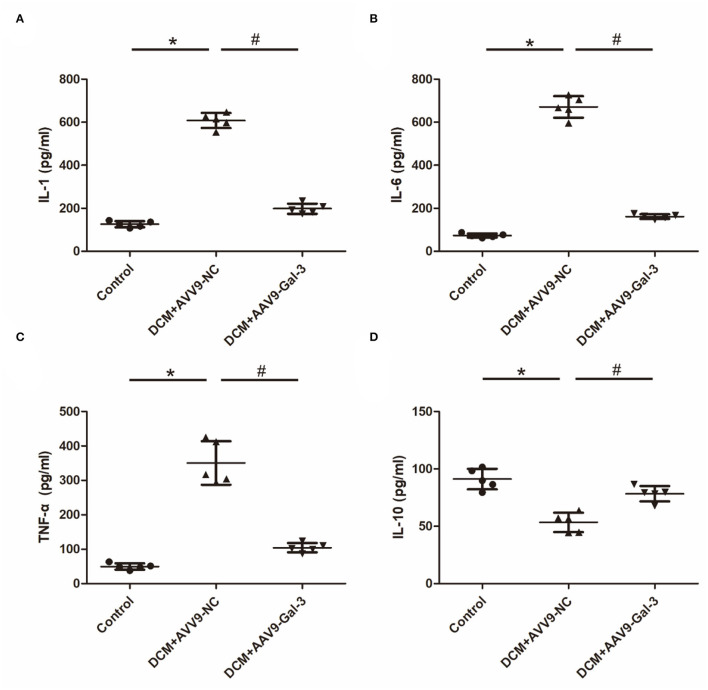

Gal-3 Inhibition Modulated Diabetes-Induced Cytokine Expression

The increase of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figures 5A–C), and the decrease of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) (Figure 5D) were observed in the DCM group. However, the decrease of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α and the increase of IL-10 were observed in the DCM+AAV9-Gal-3 group.

Figure 5.

Gal-3 inhibition modulated diabetes-induced cytokines expression (A–D) ELISA analysis of IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

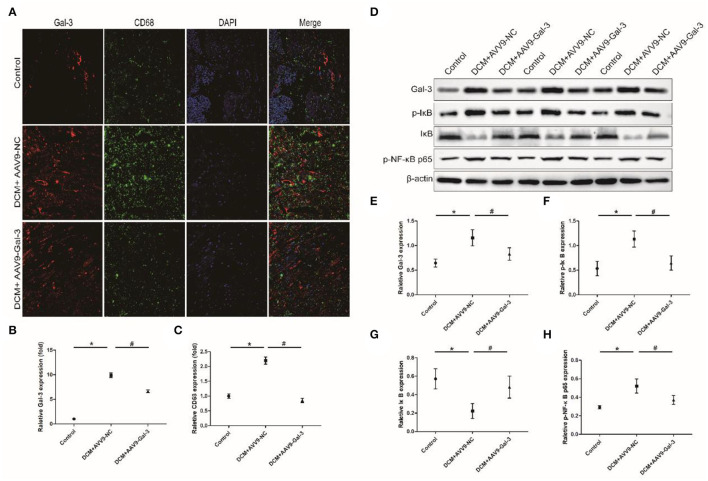

Gal-3 Inhibition Reduced Diabetes-Induced Macrophage Infiltration and NF-κB p65 Activation

Immunofluorescence staining indicated that macrophage marker (CD68) was significantly upregulated induced by STZ, whereas Gal-3 inhibition reduced CD68 expression (Figures 6A–C). Western blot analyses revealed that p-IκB and p-NF-κB p65 were increased, and IκB was decreased by diabetes, which was both reversed by Gal-3 inhibition (Figures 6D–H).

Figure 6.

Gal-3 inhibition reduced diabetes-induced macrophage infiltration and NF-κB p65 activation. (A–C) Immunofluorescence staining of CD68 and Gal-3 in heart tissue at 16 weeks after STZ injection. (D–H) Western bloting analysis of Gal-3, p-IκB, IκB and p- NF-κB p65. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. Control; # P < 0.05 vs. DCM+ AAV9-NC.

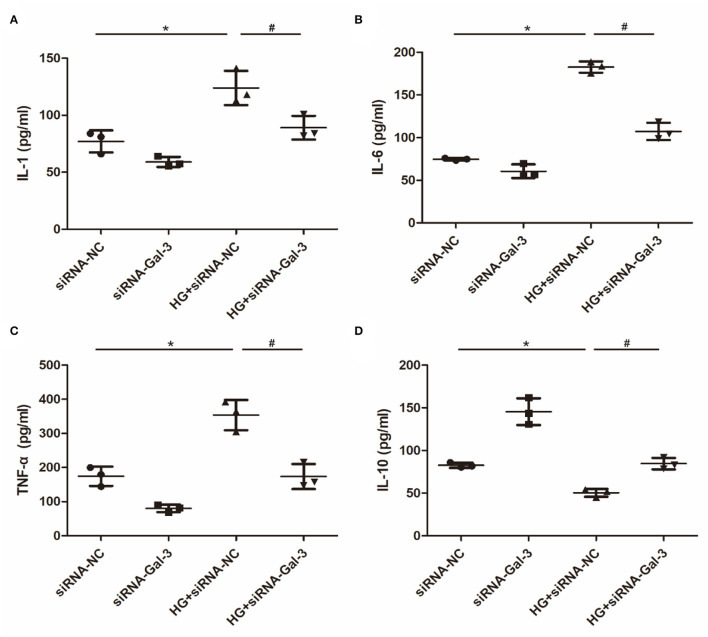

Gal-3 Knockdown Regulated HG-Induced Cytokine Expression in Macrophages

Proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figures 7A–C), were increased and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) were decreased by HG (Figure 7D). However, Gal-3 knockdown reversed the increase of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α and the decrease of IL-10.

Figure 7.

Gal-3 knockdown regulated HG (high glucose)-induced cytokines expression in macrophages (A–D) ELISA analysis of IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. siRNA-NC; #P < 0.05 vs. HG+ siRNA-NC.

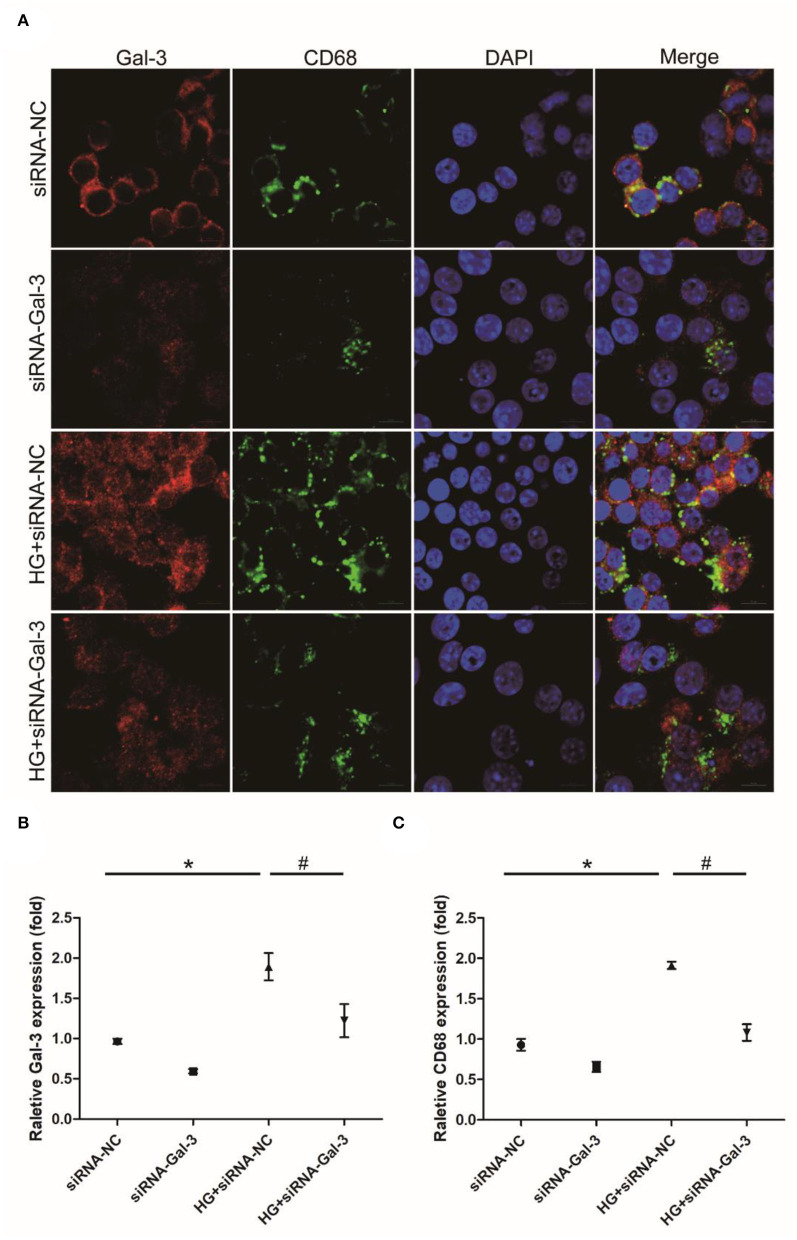

Gal-3 Knockdown Induced HG-Induced Macrophage Infiltration

Immunofluorescence staining showed that CD68 was increased by HG, which was attenuated by Gal-3 knockdown (Figures 8A–C).

Figure 8.

Gal-3 knockdown induced HG-induced macrophage infiltration (A) Immunohistochemical staining of CD68 and Gal-3. Representative analysis of CD68 (B) and Gal-3 (C). Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. siRNA-NC; # P < 0.05 vs. HG+ siRNA-NC.

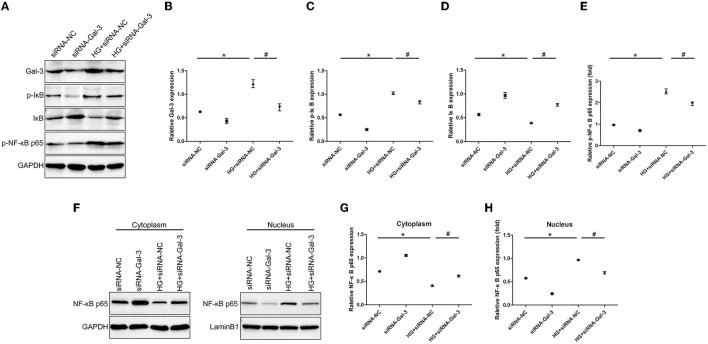

Gal-3 Knockdown Reduced NF-κB p65 Activation

Western blot analyses showed that HG-induced p-IκB and p-NF-κB p65 expression and decreased IκB (Figures 9A–E). The Gal-3 knockdown reduced p-IκB and p-NF-κB p65, as well as increased IκB. Furthermore, NF-κB p65 was decreased in the cytoplasm but increased in the nucleus (Figures 9F–H). Gal-3 knockdown reduced NF-κB p65 in the nucleus and increased it in the cytoplasm.

Figure 9.

Gal-3 knockdown reduced NF-κB p65 activation Western bloting analysis of Gal-3, p-IκB, IκB and p- NF-κB p65 (A). Representative analysis of Gal-3 (B), p-IκB (C), IκB (D) and p-NF-kB p65 (E). (F–H) Western blotting analysis of NF-κB p65 in cytoplasm and nucleus. Representative analysis of NF-κB p65 in cytoplasm and nucleus. Data are shown as mean ± SD. n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. siRNA-NC; # P < 0.05 vs. HG+ siRNA-NC.

Discussion

Our study results suggested that inhibition of Gal-3 alleviated cardiac injury and myocardial apoptosis, oxidative stress, and fibrosis in STZ-induced DCM. In addition, inhibiting Gal-3 knockdown resulted in the suppression of proinflammatory cytokines and macrophage infiltration in vivo via the mechanism of NF-κB p65 inactivation. In vitro, Gal-3 knockdown also blunted HG-induced inflammatory cytokines and macrophage infiltration, as well as NF-κB p65 inactivation. Our data identified that Gal-3 regulates DCM by the blockage of inflammation and NF-κB p65 activation. Hence, targeting Gal-3 may be a promising strategy for DCM treatment.

The DCM is caused by a complex set of pathophysiological factors. Cardiac fibrosis, which is caused by these abnormalities, is a major contributor to stiffness/diastolic dysfunction and, later, systolic dysfunction (3). The Gal-3 level is related to markers of the cardiac extracellular matrix and, therefore, emerges as a biomarker associated with death or HF hospitalization (24). The use of Gal-3 for prognosis in patients with moderate to severe HF was recommended in the 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of HF (25). New research has highlighted the use of Gal-3 as a drug target. We discovered that DCM treated with Gal-3 knockdown at the start of the experiment improved cardiac function and reduced cardiac injury biomarkers. Clinical studies have also revealed that plasma Gal-3 is an independent predictor of HF outcomes and myocardial function in patients with preserved EF, but not in patients with reduced EF (24, 26, 27). In this study, in the stage of systolic dysfunction, Gal-3 remains markedly high, indicating that further studies should be conducted to identify the role of Gal-3 in the stage of systolic dysfunction. Furthermore, Gal-3 inhibition was found to reduce fibrosis and profibrotic markers in the DCM model, including TGF-β, COL1A2, and COL3A1.

Emerging evidence indicates that Gal-3 regulates cardiac fibrosis via inflammation. The pharmacological inhibition of Gal-3 prevented cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis (28). Gal-3 blockade inhibited proinflammatory and profibrotic markers, including chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), TNF-α, and IL-1β in human cardiac fibroblasts (29). In addition, Gal-3 blockage could also inhibit isoproterenol-induced cardiac inflammation and fibrosis (30). Gal-3 blockage decreased obesity-induced cardiac dysfunction, inflammatory markers osteopontin, and CCL2, and fibrosis markers' collagen type I, TGF-β, and connective tissue growth factor (31). Gal-3 stimulated a variety of profibrotic factors, especially the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and the production of cellular debris from macrophages (32). Increased Gal-3 expression in macrophages causes alternative macrophage activation and promotes cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction (33). Gal-3 in CD206+ macrophages has also been reported to result in reparative fibrosis in myocardial infarction (34). A previous study demonstrated that CD11b-F4/80++ macrophage infiltration at 4 weeks STZ-induced diabetes was increased, but cardiac inflammation resolved at 12 weeks (35). CD68 has been used more frequently as a macrophage marker in the heart (36, 37) and CD11b+ as a macrophage marker in the liver and skin (38). More importantly, in the previous study, CD68 was not detected. We discovered that another macrophage maker, CD68, was still increased after 16 weeks. Furthermore, the STZ challenge increased proinflammatory cytokine profiles, while reducing anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles. Systemic inflammation, including circulating cytokines, chemokines, immune cells, and other inflammatory biomarkers, is present in both types of patients with diabetes (39, 40). The induction of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) has also been identified after the increase of systemic inflammatory markers in the heart of diabetic models (41–43). It has been reported that IL-10 is upregulated in reparative and pressure overload-induced fibrosis and that it is localized in T lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrating the remodeling heart. The IL-10 may regulate the cardiac fibrotic response in addition to its well-documented anti-inflammatory properties (44, 45). Though the conflict between its pro-and antifibrotic actions remains (46–48), IL-10 has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties in STZ-induced DCM (49, 50). Our data were consistent with these studies.

The HG-induced IL-1β release in human macrophages (51). In RAW264.7 macrophages, HG significantly increased the mRNA level, as well as the release of IL-1 and TNF-α (52–54). Though the role of Gal-3 in macrophage activation and proinflammation has been studied, its involvement in HG-induced inflammatory cytokine release has not been identified. In RAW264.7 macrophages, we discovered that HG induced the release of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, which was inhibited by Gal-3 inhibition.

The NF-κB is a heterodimer made up of the p50 and RelA/p65 subunits that act as a proinflammatory transcription factor and mediates the inflammatory response in macrophages (55). Under unstimulated conditions, NF-κB is localized in the cytoplasm binding IκB (56). The IκB phosphorylation and downregulation leave the NF-κB dimer free to translocate to the nucleus and initiate the transcription of targeting genes, including IL-1β and TNF-α (57). When cells are stimulated by environmental factors, NF-κB is released, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus, where it continues to mediate the transcription of target genes, such as IL-1β and TNF-α.

In macrophages, NF-κB p65 phosphorylation and localization in the nucleus also mediated inflammatory cytokines (58–60), which was correlated to many diseases (61–63). Furthermore, NF-κB p65 activates macrophage infiltration, inflammation, and myocardial fibrosis in DCM (64, 65). The HG induced NF-κB activation in RAW264.7 macrophages (66). The Gal-3 inhibitor modified citrus pectin has been proven to downregulate the expression of Gal-3 and NF-κB-p65 activation (67). In this study, we first discovered that Gal-3 inhibition blocked NF-κB-p65 activation in vivo. We also identified that Gal-3 inhibition modulates HG-induced NF-κB-p65 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Therefore, the Gal-3/NF-κB-p65 regulatory network provides novel insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of DCM.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings point to a mechanism by which Gal-3 may promote NF-κB-p65 activation, thereby alleviating DCM. The AAV9 intervention may provide a new therapeutic strategy for DCM and related heart diseases because of the potential role and therapeutic value of Gal-3 in fibrotic heart diseases.

Limitation

There are some limitations to the present study. Firstly, we failed to identify a novel mechanism of Gal-3 modulating DCM. Secondly, it is insufficient to determine that Gal-3 inhibition leads to ameliorating DCM by NF-κB-p65 activation. More experiments should be performed in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Wenzhou Medical University Animal Policy and Welfare Committee.

Author Contributions

NZ designed, drafted, and revised the manuscript. LZ and XZ performed the research and wrote the manuscript. BH and WX collected and analyzed the data. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LQ20H020011.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Gal-3

Galectin-3

- DCM

Diabetic cardiomyopathy

- i.p.

intraperitoneal injection

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- AAV-9

Adeno-associated virus 9

- HF

Heart failure

- HE

hematoxylin and eosin

- CK-MB

creatine kinase MB isoenzyme

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- COL1A2, Collagen, type I

alpha 1

- COL3A1, Collagen, type III

alpha 1

- LVEDD

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter

- LVEF, Left ventricular fractional ejection fraction, LVESD

Left ventricular end-systolic diameter

- LVFS

Left ventricular fractional shortening fraction

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β.

References

- 1.Ritchie RH, Abel ED. Basic mechanisms of diabetic heart disease. Circ Res. (2020) 126:1501–25. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillmann WH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. (2019) 124:1160–2. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia G, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: a hyperglycaemia- and insulin-resistance-induced heart disease. Diabetologia. (2018) 61:21–8. 10.1007/s00125-017-4390-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dannenberg L, Weske S, Kelm M, Levkau B, Polzin A. Cellular mechanisms and recommended drug-based therapeutic options in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 228:107920. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny HC, Abel ED. Heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circ Res. (2019) 124:121–41. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinci B. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:1881. 10.1056/NEJMc1902837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, Zelniker TA, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. (2019) 139:2528–36. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, Zelniker TA, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, et al. Use of liraglutide and risk of major cardiovascular events: a register-based cohort study in Denmark and Sweden. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2019) 7:106–14. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30320-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrie MC, Verma S, Docherty KF, Inzucchi SE, Anand I, Belohlávek J, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on worsening heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes. JAMA. (2020) 323:1353–68. 10.1001/jama.2020.1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He A, Fang W, Zhao K, Wang Y, Li J, Yang C, et al. Mast cell-deficiency protects mice from streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy. Transl Res. (2019) 208:1–14. 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L, Luo W, Qian Y, Zhu W, Qian J, Li J, et al. Luteolin protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammation and activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses. Phytomedicine. (2019) 59:152774. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo B, Huang F, Liu Y, Liang Y, Wei Z, Ke H, et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome as a molecular marker in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Physiol. (2017) 8:519. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Luo W, Han J, Khan ZA, Fang Q, Jin Y, et al. MD2 activation by direct AGE interaction drives inflammatory diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:2148. 10.1038/s41467-020-15978-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia G, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2016) 12:144–53. 10.1038/nrendo.2015.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Edgley AJ, Cox AJ, Powell AK, Wang B, Kompa AR, et al. FT011, a new anti-fibrotic drug, attenuates fibrosis and chronic heart failure in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. (2012) 14:549–62. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velickovic M, Arsenijevic A, Acovic A, Arsenijevic D, Milovanovic J, Dimitrijevic J, et al. Galectin-3, possible role in pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and potential therapeutic target. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:638258. 10.3389/fphar.2021.638258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao P, Simpson JL, Zhang J, Gibson PG. Galectin-3: its role in asthma and potential as an anti-inflammatory target. Respir Res. (2013) 14:136. 10.1186/1465-9921-14-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LC Li J, Gao J. Functions of galectin-3 and its role in fibrotic diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2014) 351:336–43. 10.1124/jpet.114.218370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins: regulators of acute and chronic inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2010) 1183:158–82. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirani N, MacKinnon AC, Nicol L, Ford P, Schambye H, Pedersen A, et al. Target inhibition of galectin-3 by inhaled TD139 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. (2021) 57:2002559. 10.1183/13993003.02559-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma UC, Pokharel S, van Brakel TJ, van Berlo JH, Cleutjens JP, Schroen B, et al. Galectin-3 marks activated macrophages in failure-prone hypertrophied hearts and contributes to cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. (2004) 110:3121–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147181.65298.4D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu L, Ruifrok WP, Meissner M, Bos EM, van Goor H, Sanjabi B, et al. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of galectin-3 prevents cardiac remodeling by interfering with myocardial fibrogenesis. Circ Heart Fail. (2013) 6:107–17. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.971168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li P, Liu S, Lu M, Bandyopadhyay G, Oh D, Imamura T, et al. Hematopoietic-derived galectin-3 causes cellular and systemic insulin resistance. Cell. (2016) 167:973–984.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Andrès N, Rossignol P, Iraqi W, Fay R, Nuée J, Ghio S, et al. Association of galectin-3 and fibrosis markers with long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, and dyssynchrony: insights from the CARE-HF (Cardiac Resynchronization in Heart Failure) trial. Eur J Heart Fail. (2012) 14:74–81. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33:1787–847. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Boer RA, Lok DJ, Jaarsma T, van der Meer P, Voors AA, Hillege HL, et al. Predictive value of plasma galectin-3 levels in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Ann Med. (2011) 43:60–8. 10.3109/07853890.2010.538080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoltze Gaborit F, Bosselmann H, Kistorp C, Iversen K, Kumler T, Gustafsson F, et al. Galectin 3: association to neurohumoral activity, echocardiographic parameters and renal function in outpatients with heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2016) 16:117. 10.1186/s12872-016-0290-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvier L, Martinez-Martinez E, Miana M, Cachofeiro V, Rousseau E, Sádaba JR, et al. The impact of galectin-3 inhibition on aldosterone-induced cardiac and renal injuries. JACC Heart Fail. (2015) 3:59–67. 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez-Martínez E, Calvier L, Fernández-Celis A, Rousseau E, Jurado-López R, Rossoni LV, et al. Galectin-3 blockade inhibits cardiac inflammation and fibrosis in experimental hyperaldosteronism and hypertension. Hypertension. (2015) 66:767–75. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergaro G., Prud'homme M, Fazal L, Merval R, Passino C, Emdin M, et al. Inhibition of galectin-3 pathway prevents isoproterenol-induced left ventricular dysfunction and fibrosis in mice. Hypertension. (2016) 67:606–12. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Martínez E, López-Ándres N, Jurado-López R, Rousseau E, Bartolomé MV, Fernández-Celis A, et al. Galectin-3 participates in cardiovascular remodeling associated with obesity. Hypertension. (2015) 66:961–9. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sano H, Hsu DK, Apgar JR, Yu L, Sharma BB, Kuwabara I, et al. Critical role of galectin-3 in phagocytosis by macrophages. J Clin Invest. (2003) 112:389–97. 10.1172/JCI17592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassaglia P, Penas F, Betazza C, Fontana Estevez F, Miksztowicz V, Martínez Naya N, et al. Genetic deletion of galectin-3 alters the temporal evolution of macrophage infiltration and healing affecting the cardiac remodeling and function after myocardial infarction in mice. Am J Pathol. (2020) 190:1789–800. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirakawa K, Endo J, Kataoka M, Katsumata Y, Yoshida N, Yamamoto T, et al. IL (Interleukin)-10-STAT3-galectin-3 axis is essential for osteopontin-producing reparative macrophage polarization after myocardial infarction. Circulation. (2018) 138:2021–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tate M, Robinson E, Green BD, McDermott BJ, Grieve DJ. Exendin-4 attenuates adverse cardiac remodelling in streptozocin-induced diabetes via specific actions on infiltrating macrophages. Basic Res Cardiol. (2016) 111:1. 10.1007/s00395-015-0518-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Couto G, Gallet R, Cambier L, Jaghatspanyan E, Makkar N, Dawkins JF, et al. Exosomal microRNA transfer into macrophages mediates cellular postconditioning. Circulation. (2017) 136:200–14. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindner D, Fitzek A, Bräuninger H, Aleshcheva G, Edler C, Meissner K, et al. Association of cardiac infection with SARS-CoV-2 in confirmed COVID-19 autopsy cases. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 5:1281–5. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:986–95. 10.1038/ni.2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2011) 11:98–107. 10.1038/nri2925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinh W, Füth R, Nickl W, Krahn T, Ellinghaus P, Scheffold T, et al. Elevated plasma levels of TNF-alpha and interleukin-6 in patients with diastolic dysfunction and glucose metabolism disorders. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2009) 8:58. 10.1186/1475-2840-8-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Zhu H, Shen E, Wan L, Arnold JM, Peng T. Deficiency of rac1 blocks NADPH oxidase activation, inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress, and reduces myocardial remodeling in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. (2010) 59:2033–42. 10.2337/db09-1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huynh K, Kiriazis H, Du XJ, Love JE, Gray SP, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, et al. Targeting the upregulation of reactive oxygen species subsequent to hyperglycemia prevents type 1 diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. (2013) 60:307–17. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westermann D, Rutschow S, Van Linthout S, Linderer A, Bücker-Gärtner C, Sobirey M, et al. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase attenuates left ventricular dysfunction by mediating pro-inflammatory cardiac cytokine levels in a mouse model of diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. (2006) 49:2507–13. 10.1007/s00125-006-0385-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Lindsey ML, Ballantyne CM, Michael LH, Smith CW, et al. IL-10 is induced in the reperfused myocardium and may modulate the reaction to injury. J Immunol. (2000) 165:2798–808. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dewald O, Ren G, Duerr GD, Zoerlein M, Klemm C, Gersch C, et al. Of mice and dogs: species-specific differences in the inflammatory response following myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol. (2004) 164:665–77. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hulsmans M, Sager HB, Roh JD, Valero-Muñoz M, Houstis NE, Iwamoto Y, et al. Cardiac macrophages promote diastolic dysfunction. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:423–40. 10.1084/jem.20171274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zymek P, Nah DY, Bujak M, Ren G, Koerting A, Leucker T, et al. Interleukin-10 is not a critical regulator of infarct healing and left ventricular remodeling. Cardiovasc Res. (2007) 74:313–22. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frangogiannis NG. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117:1450–88. 10.1093/cvr/cvaa324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alabi TD, Chegou NN, Brooks NL, Oguntibeju OO. Effects of anchomanes difformis on inflammation, apoptosis, and organ toxicity in STZ-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biomedicines. (2020) 8:29. 10.3390/biomedicines8020029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tao J, Chen H, Wang YJ, Qiu JX, Meng QQ, Zou RJ, et al. Ketogenic diet suppressed T-regulatory cells and promoted cardiac fibrosis via reducing mitochondria-associated membranes and inhibiting mitochondrial function. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2021) 2021:5512322. 10.1155/2021/5512322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SR, Lee SG, Kim SH, Kim JH, Choi E, Cho W, et al. SGLT2 inhibition modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity via ketones and insulin in diabetes with cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:2127. 10.1038/s41467-020-15983-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liao H, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhao X, Zheng D, Shen D, et al. Protective effects of thalidomide on high-glucose-induced podocyte injury through in vitro modulation of macrophage M1/M2 differentiation. J Immunol Res. (2020) 2020:8263598. 10.1155/2020/8263598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia Y, Zheng Z, Wang Y, Zhou Q, Cai W, Jia W, et al. SIRT1 is a regulator in high glucose-induced inflammatory response in RAW2647 cells. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0120849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma J, Chadban SJ, Zhao CY, Chen X, Kwan T, Panchapakesan U, et al. TLR4 activation promotes podocyte injury and interstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e97985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dorrington MG, Fraser IDC. NF-κB signaling in macrophages: dynamics, crosstalk, and signal integration. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:705. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji J, Ding K, Luo T, Zhang X, Chen A, Zhang D, et al. TRIM22 activates NF-κB signaling in glioblastoma by accelerating the degradation of IκBα. Cell Death Differ. (2021) 28:367–81. 10.1038/s41418-020-00606-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanarek N, Ben-Neriah Y. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol Rev. (2012) 246:77–94. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marwick JA, Mills R, Kay O, Michail K, Stephen J, Rossi AG, et al. Neutrophils induce macrophage anti-inflammatory reprogramming by suppressing NF-κB activation. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:665. 10.1038/s41419-018-0710-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L, Guo H, Song A, Huang J, Zhang Y, Jin S, et al. Progranulin inhibits LPS-induced macrophage M1 polarization via NF-κB and MAPK pathways. BMC Immunol. (2020) 21:32. 10.1186/s12865-020-00355-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fu YJ, Xu B, Huang SW, Luo X, Deng XL, Luo S, et al. Baicalin prevents LPS-induced activation of TLR4/NF-κB p65 pathway and inflammation in mice via inhibiting the expression of CD14. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2021) 42:88–96. 10.1038/s41401-020-0411-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li M, Rong ZJ, Cao Y, Jiang LY, Zhong D, Li CJ, et al. Utx regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway of natural stem cells to modulate macrophage migration during spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. (2021) 38:353–64. 10.1089/neu.2020.7075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He L, Weng H, Li Q, Shi G, Liu X, Du Y, et al. Lactucopicrin inhibits cytoplasmic dynein-mediated NF-κB activation in inflammated macrophages and alleviates atherogenesis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2021) 65:e2000989. 10.1002/mnfr.202000989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y, Cheng J, Su Y, Li M, Wen J, Li S. Cordycepin induces M1/M2 macrophage polarization to attenuate the liver and lung damage and immunodeficiency in immature mice with sepsis via NF-κB/p65 inhibition. J Pharm Pharmacol. (2021) 2012:rgab162. 10.1093/jpp/rgab162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Darwish MA, Abo-Youssef AM, Messiha BAS, Abo-Saif AA, Abdel-Bakky MS. Resveratrol inhibits macrophage infiltration of pancreatic islets in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic mice via attenuation of the CXCL16/NF-κB p65 signaling pathway. Life Sci. (2021) 272:119250. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malek V, Gaikwad AB. Telmisartan and thiorphan combination treatment attenuates fibrosis and apoptosis in preventing diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. (2019) 115:373–84. 10.1093/cvr/cvy226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng CI, Chen PH, Lin YC, Kao YH. High glucose activates Raw2647 macrophages through RhoA kinase-mediated signaling pathway. Cell Signal. (2015) 27:283–92. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xu GR, Zhang C, Yang HX, Sun JH, Zhang Y, Yao TT, et al. Modified citrus pectin ameliorates myocardial fibrosis and inflammation via suppressing galectin-3 and TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 126:110071. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.