Abstract

Aims

Important differences have been shown in alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking prevalence, patterns and consequences among individuals from different racial backgrounds. Alcohol and nicotine are often co-used, and the association between drinking and smoking may differ between racial groups—a question explored in the present study.

Methods

Data from the NIAAA natural history and screening protocols were utilized; non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals were included in the analyses [N = 1692; 65.2% male; 58.3% met criteria for current alcohol use disorder (AUD); 37.8% were current cigarette smokers]. Bivariate associations between assessments related to alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking were examined, and the strength and direction of these associations were compared between the two groups.

Results

The sample included 796 Black and 896 White individuals. Black participants had higher frequency (P < 0.0001) and severity (P = 0.007) of AUD, as well as higher frequency (P < 0.0001) of cigarette smoking. Bivariate analyses showed that the expected positive associations between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking, observed among White individuals, were blunted or absent among Black individuals [age at first cigarette—AUD identification test (AUDIT) score: F(1, 292) = 7.60, P = 0.006; cigarette pack years—AUDIT score: F(1, 1111) = 10.97, P = 0.001].

Conclusions

Some decoupling in the association between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking was found among Black compared to White individuals. The sample was drawn from a specific population enrolled in alcohol research protocols, which is a limitation of the present study. These preliminary findings highlight the importance of considering racial/ethnic background in preventive and therapeutic strategies for comorbid alcohol and nicotine use.

Short Summary: This study investigated differential association between alcohol drinking andcigarette smoking across non-Hispanic Black and White participants of analcohol research program. Results found decoupling in the drinking–smoking link among Black versus White individuals, highlighting theimportance of considering racial/ethnic background in substance useresearch and treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Hazardous alcohol drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD) are global public health concerns, contributing to a myriad of negative social, economic, morbidity and mortality consequences. In 2018, 26% of people reported having engaged in binge drinking, i.e. five or more drinks for men or four or more for women on the same occasion, and 6.6% reported heavy alcohol use, i.e. binge drinking for 5 or more days in the past month (NSDUH, 2018). High rates of alcohol consumption and risky drinking patterns are responsible for pathological consequences, such as alcohol-associated liver disease, and represent critical risk factors for several cancers (WHO, 2014). Furthermore, risky drinking patterns are associated with functional disabilities, such as impaired mental health, social dysfunction and premature mortality (Samokhvalov et al., 2010; Stahre et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2015).

Previous studies have identified important differences in alcohol consumption and disproportionate negative health consequences among disadvantaged and underserved groups (Caetano et al., 1998; Galvan and Caetano, 2003; Chartier and Caetano, 2010). Although the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported that past-year alcohol use was overall more prevalent among White (73.9%) than Black (62.6%) adults (SAMHSA, 2016), frequency of drinking among Black individuals increases as they get older, and in their 30s, rates are higher among Black adults compared to their White counterparts (Muthén and Muthén, 2000; Mulia et al., 2017). In addition to racial differences in the prevalence and frequency of alcohol drinking, from age 15, Black females report greater consumption of liquor relative to wine or beer, compared to other racial groups (Chung et al., 2014). This early use of liquor may contribute, at least in part, to early alcohol-related consequences and racial differences in some drinking patterns (Bluthenthal et al., 2005; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2010). Non-Hispanic White individuals have greater odds of developing AUD compared to non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals (Hasin et al., 2007; Chartier and Caetano, 2010). However, racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to meet criteria for current AUD for a longer period of time and have a greater likelihood of recurrent AUD than White individuals (Grant et al., 2012). Prior research also indicates that racial and ethnic minorities, compared to White individuals, are at greater risk of various alcohol-related adverse consequences (Caetano et al., 1998; Mulia et al., 2017), including increased risk for developing alcohol-associated liver disease (Flores et al., 2008), alcohol-related esophageal and pancreatic cancer (Polednak, 2007) and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (Russo et al., 2004).

Cigarette smoking is another leading cause of disability and premature death in the USA and worldwide. Tobacco use and tobacco-related diseases result in over 480,000 deaths per year and contribute to billions of dollars in medical costs and loss of productivity (USDHHS, 2014). Similar to alcohol drinking, considerable racial differences have been reported in various measures and outcomes of cigarette smoking. For example, in a study investigating cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking, Black youth, compared to other racial groups, were less likely to start smoking and to become daily smokers (Kandel et al., 2004). This finding is consistent with existing evidence, suggesting that the prevalence of cigarette smoking is highest among White youth, but later in adulthood, the pattern reverses and smoking becomes more prevalent among Black individuals (King et al., 2004; Pampel, 2008).

Previous research consistently shows that smoking-related negative consequences are more prevalent among Black than White individuals (USDHHS, 1998; DeLancey et al., 2008; Trinidad et al., 2009, 2011). Although Black people typically have a later age of smoking initiation and smoke fewer cigarettes per day than White people (Schoenborn et al., 2013), they experience higher incidence and mortality from smoking-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (USDHHS, 1998; Haiman et al., 2006; Fagan et al., 2007; DeLancey et al., 2008; Underwood et al., 2012; Babb et al., 2017). Additionally, despite lower prevalence of cigarette smoking, Black individuals are less likely to successfully quit smoking (USDHHS, 1998; King et al., 2004; Trinidad et al., 2005), even though a higher percentage of Black people report that they want to quit smoking (USDHHS, 1998; Babb et al., 2017). Evidence also suggests that Black individuals smoke for a longer period of time (i.e. higher number of years of daily smoking), compared to White individuals (Siahpush et al., 2010), which may explain, at least in part, higher incidence and mortality from smoking-related health consequences among Black people.

While alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking are each a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, the co-use of both drugs is also highly prevalent. Individuals who drink more alcohol tend to smoke more cigarettes and vice versa. According to the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), 46 million adults reported both alcohol and tobacco use within the past year, and of those individuals, 6 million were diagnosed with both alcohol and nicotine dependence (Falk et al., 2008). Data from the 2002–2015 National Household Survey on Drug Use found that the prevalence of cigarette smoking was more than two times higher among individuals with hazardous alcohol use and/or AUD, compared to those without (Weinberger et al., 2017). Several studies have also found that cigarette smoking is positively associated with the frequency of alcohol binge drinking (Satre et al., 2007; Blazer and Wu, 2009; Bryant and Kim, 2012).

There are several behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms underlying alcohol and nicotine co-use. Previous research has demonstrated that using one of these drugs may enhance the subjective response, pleasant effects and craving for the other drug (Burton and Tiffany, 1997; Kouri et al., 2004; King and Epstein, 2005; Sayette et al., 2005; Piasecki et al., 2008; King et al., 2009). This increase in craving and subjective effects and the subsequent cue-conditioned relationship via Pavlovian conditioning results in synergistic reinforcing effects of alcohol and nicotine by increasing the rewarding effects of each drug (Shiffman et al., 2007; Verplaetse and McKee, 2017). In addition, both alcohol and nicotine act upon brain regions involved in reward processing, emotion regulation, memory and cognitive control (Funk et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that alcohol and nicotine interact in the same neurocircuitries, such as mesolimbic pathways (Funk et al., 2006; King et al., 2009), which may play a role in increased craving, tolerance and response to both drugs. The disinhibiting effects of alcohol may lead to increased smoking through mechanisms such as weakened self-control or self-regulation, increased impulsivity, cross-tolerance and/or conditioned associations between smoking and drinking (Niaura et al., 1988; Abrams et al., 1992; Piasecki et al., 2008). Consuming alcohol may also disrupt cognitive functions, such as attention, and may lead to a focus shift on smoking urge and desire (Steele and Josephs, 1990; Sayette et al., 2005).

It is important to note that previous research has found differences in the relationships between certain health behaviors and outcomes among racial minority groups versus White individuals. As an example, a previous study found that the relationship between heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems was less prominent among Black men compared to White men, which may be attributed to Black individuals experiencing higher rates of alcohol-related problems, even at lower levels of heavy drinking (Witbrodt et al., 2014). It is plausible to hypothesize that, in addition to differences in the severity and consequences of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking summarized above, the association between these two closely linked health behaviors may also differ between racial/ethnic groups. Understanding these differences may provide novel information and guide ongoing endeavors to develop more effective preventive and therapeutic interventions tailored to the specific needs and unique characteristics of each sub-population. The goal of this study was to investigate possible racial differences in the association between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking in a relatively large sample of non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals enrolled in alcohol research studies.

METHODS

Design, setting and participants

This study used cross-sectional data from Institutional Review Boards approved screening and natural history protocols (98-AA-0009, 05-AA-0121 and 14-AA-0181) of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), conducted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Adult individuals were recruited through word of mouth and electronic/printed advertisements and were evaluated through a phone screen followed by an in-person screening visit. The screening visit included a comprehensive evaluation of medical and psychiatric history, face-to-face interviews and a battery of subjective and objective assessments. Participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment and received monetary compensation for their time and participation. These screening and natural history protocols enrolled treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking individuals with AUD, diagnosed based on the DSM criteria, as well as healthy individuals (i.e. no diagnosis of AUD). Treatment-seeking status was determined based on a question during the phone screen: ‘Are you interested in research studies that include an inpatient treatment program to help you stop drinking, or would you just like to participate in a research study?’. Individuals who were seeking treatment underwent an inpatient treatment program of approximately 4 weeks, while others were evaluated during a single outpatient visit. Inpatient assessments were performed approximately 1 week after admission to prevent potential confounding effects of alcohol withdrawal. Optional smoking treatment was also offered to participants in the inpatient treatment program.

Assessments

Race

Participants were asked to self-report their race according to the following categories: (a) American Indian/Alaska Native, (b) Asian, (c) Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, (d) Black/African American, (e) White, (f) more than one race or (g) unknown or not reported. Self-reported ethnicity was also inquired, which included the following choices: (a) Hispanic or Latino or (b) Not Hispanic or Latino. For this study, non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals were selected and included in the analyses. We were not able to include other racial/ethnic groups due to their small sample sizes in the dataset. Additionally, the study was not powered to disaggregate the data for acculturation and national background, which are important factors to consider (Marin et al., 1989; Kondo et al., 2016; Rodriquez et al., 2019).

Alcohol drinking data

The Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Text Revision (SCID-IV-TR) or DSM-5 (SCID-5) was administered, depending on each participant’s time of enrollment, to provide a comprehensive evaluation of mental health, including the presence of alcohol and other substance use disorders. Here, the AUD group refers to individuals who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence and those who met DSM-5 criteria for AUD in the past 12 months. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Allen et al., 1997) was also administered in the parent protocols. AUDIT is a 10-item screening assessment with three subscales: AUDIT-C, three questions on the consumption or hazardous alcohol use; AUDIT-D, three questions on alcohol dependence; AUDIT-H, four questions on harmful alcohol use. A summed score of all the items is also calculated as AUDIT total score, with a maximum of 40. An AUDIT total score of 1–7 indicates low risk, 8–15 indicates moderate risk and 16 or above indicates high risk of alcohol problems. Data on age at first drink were acquired from the Lifetime Drinking History (Skinner and Sheu, 1982), which is a structured interview that encompasses lifetime retrospective information on alcohol drinking.

Cigarette smoking data

Smoking-related data were acquired from an in-house Smoking History Questionnaire that collects various information such as smoking status (‘If you are not a smoker, check here’), age at first cigarette (‘What was your age when you had the first cigarette?’), number of cigarettes smoked per day (‘How many cigarettes do you smoke a day?’) and number of smoking years (‘How many years have you smoked cigarettes?’). Cigarette pack years, a commonly used metric indicating the severity of lifetime tobacco smoking, was calculated by multiplying the number of cigarette packs smoked per day by the number of years of smoking.

Statistical analysis

All data were tested for normal distribution and statistical outliers prior to analysis. To characterize the study sample, continuous and categorical variables were first compared between the two groups (i.e. Black versus White individuals) using independent samples t-test and chi-square test, respectively. Effect sizes were also calculated for continuous variables using Cohen’s d and for categorical variables using eta squared. Continuous variables are presented as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD); categorical variables are presented as number (n) and percent (%). Next, the association between each alcohol drinking variable (i.e. AUDIT total score and age at first drink) and each cigarette smoking variable (i.e. cigarette pack years and age at first cigarette) was compared between the two groups in subsets of individuals who had available data for both variables (each model included one drinking variable and one smoking variable). Bivariate correlations between these variables are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Given that we did not want to assume a cause and effect direction between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking variables, Deming regression was applied to find the line of best fit for these two-dimensional datasets, while accounting for and minimizing errors in both X and Y variables. Using this method, a regression line between drinking and smoking variables was fitted for each group and the slopes of the two lines were compared between the two groups. As a confirmatory next step, and in order to control for potential covariates, hierarchical (2 steps) multiple linear regressions were run with alcohol drinking measures (AUDIT total score and age at first drink) as the dependent variable; separate models were run for each drinking–smoking variable pair. Model 1 included race, smoking and the interaction between the two as predictors; Model 2 included a list of potential covariates (i.e. sex, age, years of education, household income and treatment-seeking status) in addition to the predictors included in Model 1. Forced entry method was applied for including and testing the predictors in the aforementioned multiple regression models. Significance level was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed) for all analyses. IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 for Windows (Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 for Windows (La Jolla, CA, USA) were used for data analysis and visualization.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample

A total of 1692 participants, including 796 Black individuals and 896 White individuals, were included in this study. The aggregate sample had a mean age of 39.7 (SD = 12.5), 58.3% met criteria for current AUD and 37.8% were current cigarette smokers.

Table 1 provides a comparison of demographic characteristics between the two groups. Significant differences were found in terms of age, years of education, household income and treatment-seeking status. Specifically, in this sample, Black participants were older, had lower years of education and household income and were less likely to be treatment-seeking, compared to White participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics between Black and White individuals

| Total sample | Black individuals | White individuals | Test statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) Female Male |

589 (34.8) 1103 (65.2) |

262 (32.9) 534 (67.1) |

327 (36.5) 569 (63.5) |

χ2(1) = 2.38, P = 0.068; η2 = 0.038 |

| Age, years, M (SD) | 39.71 (12.50) | 41.58 (11.57) | 38.06 (13.05) | t(1690) = 5.84, P < 0.0001; d = 0.285 |

| Years of education, years, M (SD) | 14.44 (3.15) | 13.39 (2.92) | 15.41 (3.03) | t(1565) = −13.36, P < 0.0001; d = 0.679 |

| Household income, n (%) <$5000 $5000–$9999 $10,000–$19,999 $20,000–$29,999 $30,000–$39,999 $40,000–$49,999 $50,000–$74,999 $75,000–$100,000 >$100,000 |

252 (14.9) 88 (5.2) 146 (8.6) 183 (10.8) 155 (92) 123 (7.3) 181 (10.7) 94 (5.6) 190 (11.2) |

167 (21.0) 55 (6.9) 102 (12.8) 83 (10.4) 80 (10.1) 61 (7.7) 84 (10.6) 34 (4.3) 38 (4.8) |

85 (9.5) 33 (3.7) 44 (4.9) 100 (11.2) 75 (8.4) 62 (6.9) 97 (10.8) 60 (6.7) 152 (17.0) |

χ2(1) = 134.48, P < 0.0001; η2 = 0.275 |

| Treatment seeking status, n (%) Treatment seeker Non-treatment seeker |

715 (42.3) 977 (57.7) |

301 (37.8) 495 (62.2) |

414 (46.2) 482 (53.8) |

χ2(1) = 12.16, P < 0.0001; η2 = 0.085 |

Table 2 provides a comparison of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking variables between the two groups. Higher frequency and severity of alcohol use were found among Black individuals, as indicated by significantly more individuals with AUD diagnosis [χ2(1) = 18.12, P < 0.0001] and significantly higher AUDIT scores [t(1127) = 2.68, P = 0.007], compared to White individuals. Significantly higher number of smokers were also found among Black participants [χ2(1) = 17.82, P < 0.0001], while other smoking measures, including cigarette pack years and age at first cigarette, were not significantly different between the two groups (P’s ≥ 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking variables between Black and White individuals

| Total sample | Black individuals | White individuals | Test statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUD diagnosisa, n (%) Yes No |

987 (59.9) 690 (41.1) |

506 (64.3) 281 (35.7) |

481 (54.0) 409 (46.0) |

χ2(1) = 18.12, P < 0.0001; η2 = 0.104 |

| AUDIT total score, M (SD) | 12.13 (10.73) n = 1129 |

13.01 (10.91) n = 548 |

11.30 (10.51) n = 581 |

t(1127) = 2.68, P = 0.007; d = 0.160 |

| Age at first drink, years, M (SD) | 16.26 (3.71) n = 1034 |

16.38 (4.16) n = 504 |

16.15 (3.22) n = 530 |

t(1032) = 0.99, P = 0.325; d = 0.062 |

| Cigarette smoker, n (%) Yes No |

639 (37.8) 961 (56.8) |

340 (45.5) 408 (54.5) |

299 (35.1) 553 (64.9) |

χ2(1) = 17.82, P < 0.0001; η2 = 0.106 |

| Cigarette pack years, M (SD) | 5.42 (10.58) n = 1591 |

5.45 (10.20) n = 743 |

5.40 (10.90) n = 848 |

t(1589) = 0.10, P = 0.924; d = 0.005 |

| Age at first cigarette, years, M (SD) | 16.25 (5.54) n = 630 |

16.53 (5.51) n = 332 |

15.94 (5.58) n = 298 |

t(628) = 1.32, P = 0.187; d = 0.106 |

aDSM-IV-TR diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence or DSM-5 diagnosis of alcohol use disorder in the past 12 months.

Associations between measures of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking

Table 3 outlines the results of Deming regressions examining bivariate associations between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking variables. The results were statistically significant for AUDIT total score (as described below) but not for age at first drink (for additional details, see the Supplement).

Table 3.

Comparison of the alcohol drinking–cigarette smoking regression lines between Black and White individuals

| Age at first cigarette | Cigarette pack years | |

|---|---|---|

| AUDIT total score | White: β = −3.04, F(1, 110) = 9.41, P = 0.002 Black: β = −0.01, F(1, 182) = 0.003, P = 0.95 Comparison: F(1, 292) = 7.60, P = 0.006 |

White: β = 1.69, F(1, 574) = 187.90, P < 0.0001 Black: β = 1.34, F(1, 537) = 94.10, P < 0.001 Comparison: F(1, 1111) = 10.97, P = 0.001 |

| Age at first drink | White: β = 2.35, F(1, 106) = 17.99, P < 0.0001 Black: β = 1.92, F(1, 170) = 27.08, P < 0.0001 Comparison: F(1, 276) = 0.57, P = 0.45 |

White: β = −0.58, F(1, 523) = 39.60, P < 0.0001 Black: β = −0.75, F(1, 484) = 26.37, P < 0.0001 Comparison: F(1, 1007) = 0.166, P = 0.68 |

For each bivariate association between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking variables, a regression line was fitted for each group, using Deming regression, and the slopes of the two lines were compared between the two groups. The first two lines in each cell report the results in each group (White, Black), examining whether the slope of the respective regression line is significantly deviated from zero. The third line in each test reports the results of the comparison test, examining the difference between the slopes of the two regression lines.

Earlier age at first cigarette was associated with higher AUDIT scores among White [β = −3.04, F(1, 110) = 9.41, P = 0.002] but not Black [β = −0.01, F(1, 182) = 0.003, P = 0.95)] individuals, and the regression lines had significantly different slopes [F(1, 292) = 7.60, P = 0.006] (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Table 4 outlines the results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis, which found a significant race × age at first cigarette effect on AUDIT total score, both without (β = −0.58, t = −2.50, P = 0.01) and with (β = −0.45, t = −2.47, P = 0.01) controlling for sex, age, years of education, household income and treatment-seeking status (Table 4). It should be noted that Model 1 had a low R2, questioning the goodness-of-fit of this model for the data, which considerably improved in Model 2, after including the covariates.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot and regression lines of the association between AUDIT score and age at first cigarette.

Table 4.

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis including age at first cigarette as an independent variable and AUDIT total score as the dependent variable

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | t | P | B | SE (B) | Β | t | P | |

| Race | 11.607 | 3.764 | 0.573 | 3.083 | 0.002 | 5.791 | 2.984 | 0.286 | 1.941 | 0.053 |

| Age at first cigarette | 0.552 | 0.308 | 0.318 | 1.795 | 0.074 | 0.396 | 0.239 | 0.228 | 1.655 | 0.099 |

| Race × age at first cigarette | −0.558 | 0.223 | −0.586 | −2.501 | 0.013 | −0.431 | 0.174 | −0.452 | −2.472 | 0.014 |

| Sex | 0.843 | 1.027 | 0.038 | 0.821 | 0.412 | |||||

| Age | −0.005 | 0.039 | −0.006 | −0.129 | 0.897 | |||||

| Years of education | −0.252 | 0.160 | −0.080 | −1.574 | 0.117 | |||||

| Household income | −0.028 | 0.196 | −0.008 | −0.145 | 0.885 | |||||

| Treatment seeking status | 13.018 | 0.981 | 0.656 | 13.276 | <0.001 | |||||

| Overall model | F(3, 278) = 5.105, P = 0.002, R2 = 0.052 | F(8, 273) = 27.217, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.444 | ||||||||

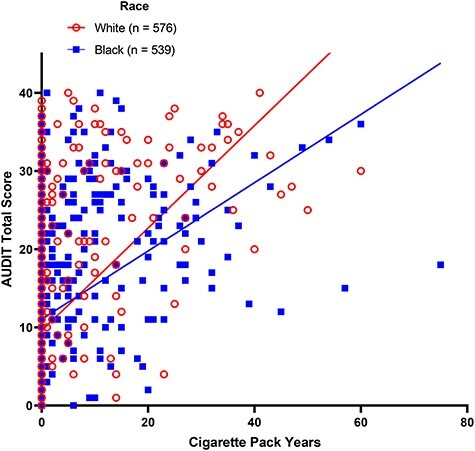

The positive association between cigarette pack years and AUDIT scores was stronger among White [β = 1.69, F(1, 574) = 187.90, P < 0.0001)] than Black [β = 1.34, F(1, 537) = 94.10, P < 0.001] individuals, and the regression lines had significantly different slopes [F(1, 111) = 10.97, P = 0.001] (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Table 5 outlines the results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis, which found a significant race × cigarette pack years effect on AUDIT total score (β = 0.25, t = 3.03, P = 0.002), but the interaction was not significant after controlling for sex, age, years of education, household income and treatment-seeking status (β = −0.09, t = −1.46, P = 0.14) (Table 5). Similar to above, Model 1 had a low R2, which considerably improved in Model 2, after including the covariates. When cigarettes per day was examined instead of pack years, a similar pattern was observed (Supplementary Fig. S1), but the results did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Tables S2–S4).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot and regression lines of the association between AUDIT score and cigarette pack years.

Table 5.

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis including cigarette pack years as an independent variable and AUDIT total score as the dependent variable

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | t | P | B | SE (B) | Β | t | P | |

| Race | −1.184 | 0.662 | −0.054 | −1.790 | 0.074 | −0.425 | 0.536 | −0.019 | −0.794 | 0.427 |

| Cigarette pack years | 0.224 | 0.104 | 0.185 | 2.163 | 0.031 | 0.311 | 0.078 | 0.257 | 3.976 | <0.001 |

| Race × cigarette pack years | 0.209 | 0.069 | 0.259 | 3.033 | 0.002 | −0.077 | 0.052 | −0.095 | −1.462 | 0.144 |

| Sex | 2.302 | 0.481 | 0.101 | 4.782 | <0.001 | |||||

| Age | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.427 | 0.670 | |||||

| Years of education | −0.409 | 0.080 | −0.120 | −5.107 | <0.001 | |||||

| Household income | −0.208 | 0.094 | −0.050 | −2.204 | 0.028 | |||||

| Treatment seeking status | 17.194 | 0.678 | 0.607 | 25.356 | <0.001 | |||||

| Overall model | F(3, 1026) = 82.648, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.195 | F(8, 1021) = 160.097, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.556 | ||||||||

The association between age at first drink and smoking variables was not significantly different between the two groups (for more details, see Table 3 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S4–S6).

DISCUSSION

This work examined racial differences in the association between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals, utilizing data from screening and natural history protocols at NIAAA/NIH. Univariate analyses to characterize this sample showed that Black participants had higher severity of alcohol use, while the severity of cigarette smoking was not significantly different between the two groups. The main research question of this study was examined through bivariate analyses and found that the expected positive association between measures of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking, which was observed among White individuals, was significantly blunted or even absent among Black individuals. Specifically, lower age at first cigarette was associated with higher AUDIT scores among White participants, but no association was found among Black participants. Higher cigarette pack years was associated with higher AUDIT scores in both groups, but this association was significantly weaker among Black participants, compared to White participants. It should be noted that, from a statistical standpoint, the findings were stronger for age at first cigarette, and the results for cigarette pack years were not significant in the multiple regression analyses after adding a list of covariates (Model 2). That said, the numbers included in each analysis were different, based on the availability of data, and data collection was not geared toward these specific questions. Therefore, while the main take-home message from this study remains the overall trend of differences between the two groups (rather than pure statistical results), replication in larger and more representative samples is needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

A variety of factors may contribute to potential differences in patterns and correlates of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking among Black and White individuals. Although not directly examined in the present study, environmental factors related to systemic and/or structural racism have been shown to play a central role in the development and progression of addictive behaviors and drug use. For example, previous work indicates that disadvantaged neighborhoods have an overconcentration of liquor stores (Gorman and Speer, 1997; LaVeist and Wallace Jr, 2000; Bluthenthal et al., 2008), as well as convenience stores that sell cigarettes (Laws et al., 2002; Fakunle et al., 2010). Proximity to a high concentration of liquor stores increases physical availability of alcohol which, in turn, encourages heavy alcohol drinking (Gruenewald et al., 2002; Truong and Sturm, 2007; Schonlau et al., 2008). A previous study found that living in neighborhoods with higher proportion of Black individuals was associated with heavy use of distilled spirits or liquor, leading to higher number of negative drinking consequences (Jones-Webb and Karriker-Jaffe, 2013). In addition, exposure to tobacco marketing is associated with increased likelihood of youth initiating smoking (Henriksen et al., 2008; Henriksen et al., 2010) and lower probability of smoking cessation success (Germain et al., 2010). Marketing practices that include advertisements for malt liquor (Jones-Webb et al., 2008; McKee et al., 2011) and tobacco (Widome et al., 2013) are more common in some disadvantaged neighborhoods. Another noteworthy factor related to institutional racism includes systemic differences in access to resources and treatment for alcohol and substance use. Historically, Black individuals with AUD are less likely to receive and/or complete treatment for alcohol problems, compared to White individuals (Saloner and Lê Cook, 2013; Vaeth et al., 2017). We observed a similar pattern in our data, as a higher percentage of treatment-seeking individuals were found among White than Black participants. Previous research also indicates that White individuals, compared to Black individuals, have more access to resources for quitting smoking, as well as greater utilization of smoking cessation treatment programs (Pampel, 2008; Babb et al., 2017).

Our design, setting and sample characteristics are important factors in interpreting these findings. The study sample included both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking individuals with AUD, as well as healthy controls, enrolled in an alcohol research program. Within this specific sample, we found a higher frequency of AUD diagnosis among Black individuals, compared to White individuals, which is not consistent with some epidemiological reports suggestive of higher odds of AUD among White than Black individuals (Hasin et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2015). We also found that Black participants had higher severity of alcohol use than White participants according to AUDIT scores. Previous research is not conclusive in this regards, as some studies show similar or higher severity of alcohol use among White than Black individuals (Grant et al., 2004; SAMHSA, 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Bensley et al., 2018), while others have found the opposite (Mulia et al., 2009; Bensley et al., 2018). The age at first drink was not significantly different between White and Black participants in the present study; however, existing evidence suggests that White individuals initiate alcohol drinking earlier, compared to other racial/ethnic groups (Faden, 2006). While our study was conducted among adults, previous data show that Black youth have the lowest rates of drinking and being drunk across racial/ethnic groups (O'Malley et al., 1998), and start drinking alcohol at an older age, compared to White youth (Chen et al., 2004; Faden, 2006). One possible contributing factor to this phenomenon is drinking with peers at college, in which Black individuals are less likely to participate than White individuals (Wade and Peralta, 2017).

In terms of cigarette smoking, our sample had a higher percent of smokers among Black than White participants. The majority of previous research has shown lower frequency of smoking among Black individuals, with some data suggesting more successful quitting among White people (DeLancey et al., 2008; Trinidad et al., 2009; Babb et al., 2017). Additionally, research has identified relatively similar rates of alcohol and nicotine co-use among both White and Black individuals, with White individuals having slightly higher prevalence of co-use than Black individuals (18.2 versus 12.6%) (Falk et al., 2008). It is important to note that the participants of the present study were all enrolled as part of alcohol research protocols. Therefore, an expected higher percentage of individuals with AUD was observed within our sample, compared to the general population. It is reasonable to assume that the pattern and severity of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking and their co-use within our specific study sample might be different from broader populations, another reason why our results must be considered preliminary and need to be replicated in larger community-based samples.

Despite different percentage of cigarette smokers between the two groups, other smoking-related measures in this study were not significantly different between Black and White participants. Specifically, indicators of the severity of smoking-related behavior (age at first cigarette, cigarettes per day and cigarette pack years) were not significantly different between the two groups. While evidence from national data suggest that Black individuals smoke fewer cigarettes per day (Ho and Elo, 2013), have a later age of smoking onset (Roberts et al., 2016) and have lower average cigarette pack years, compared to White individuals (Holford et al., 2016), Black participants in our sample were, overall, older than Whites participants, which may have partially contributed to lack of an observed difference in smoking-related measures between the two groups. It is important to note that our dataset included age at first cigarette rather than the age when regular smoking started. The only interaction that remained significant in multiple regression after adding a list of covariates (Model 2) was related to age at first cigarette and its interaction with race on AUDIT total scores. While Deming regression and linear multiple regression without covariates (Model 1) also showed a significant effect for cigarette pack years, the statistical significance was washed out in multiple regression with covariates (Model 2). Cigarette pack years is typically known as a cumulative measure of long-term exposure to cigarette smoking and its harms; however, it may not be the most accurate assessment because, for example, it does not address potential differences in dosage (e.g. nicotine intake per cigarette), cigarette brands, etc. Of note, a previous study found that, despite comparable number of cigarettes smokes per day, Black individuals had higher levels of cotinine per cigarette smoked than White individuals, possibly due to slower clearance of cotinine and higher intake of nicotine per cigarette (Pérez-Stable et al., 1998). In addition to the self-report measures included in our study, future research must incorporate objective measures of alcohol and nicotine intake to better understand the dose–response relationship between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking.

Some of the differences between our study and previous ones could be related to the specific setting and/or characteristics of the sample enrolled. For example, the number of Black individuals in our sample was almost equal to the number of White individuals, which is not representative of the US population, where Black individuals make up around 15% of the population. In addition, our study was conducted in a research hospital among people who sought to participate in research studies; therefore may not represent broader settings (e.g. primary care) and populations (e.g. nationally representative). Nevertheless, the study holds important strengths and generates plausible and testable hypotheses for future research. One of the strengths of this study was a relatively balanced number of Black and White individuals, which is an important factor in terms of examining differences across the two groups. Additionally, detailed phenotypic data on both alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking enabled us to examine racial differences in the relationship between these two closely linked health behaviors. While we had a smaller sample size than nationally representative studies (e.g. NSDUH or NESARC), the specific characteristics of our sample, including high prevalence of AUD leading to higher statistical power, well-controlled research setting and in-depth phenotyping provided a strong platform and a unique opportunity to start examining the relationship between different measures of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking and to examine possible racial differences in this regard.

There are also several limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, because of the cross-sectional design of this study, results cannot imply any temporality, direction or causation. This factor is particularly important in interpretation of the bivariate analyses, where associations between drinking and smoking were assessed, but a causal link cannot be established. Future research may employ longitudinal methods to better understand the interaction between drinking and smoking patterns and to provide predictive models to study the mechanisms underlying the link between these two health behaviors. Secondly, the present study did not assess specific negative consequences of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking, such as medical, psychological, social, legal and financial burdens. Investigating differences among Black and White individuals in experience of such consequences may provide insight on how to design and implement culturally appropriate interventions. Thirdly, although most participants completed the assessments, there were some missing data, mainly due to changes in the screening and natural history protocols over time. Of note, we did explore possible reasons behind missing data and concluded that, beyond time of enrollment, the pattern of missing data was random in our dataset. Fourthly, the study relied on self-reported data and no objective measures of alcohol drinking or cigarette smoking were available, which may introduce recall bias and affect the interpretability of our findings. Fifthly, our study sample was drawn from a specific population enrolled in alcohol research protocols, which is not representative of the general population and might be subject to sampling bias in terms of participants’ drinking and smoking characteristics. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations and settings and must be confirmed in larger and nationally representative samples. Finally, this study focused on non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to the distribution of participants. Future research should include other racial and ethnic minority groups to provide a more comprehensive picture of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking and the relationship between the two among different racial and ethnic groups.

In summary, our study investigated racial differences in the relationship between alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking measures and found less prominent or no associations among Black compared to White participants of an alcohol research program. While preliminary and in need of replication in larger and more diverse samples, these findings can contribute to generating research questions surrounding racial disparities in substance use, clinical practices involved in treating racially diverse communities and treatment programs of comorbid alcohol and nicotine use. Additionally, these results suggest that minoritized background and lived experiences of racism are important factors to consider in the conceptualization of comorbid alcohol and nicotine use. Future studies should include specific questions on experiences of racism, discrimination and other forms of oppression, as they relate to comorbid alcohol and nicotine use. Future studies may also investigate racial/ethnic differences in negative health outcomes related to alcohol drinking (e.g. esophageal or pancreatic cancer, alcohol-associate liver disease), cigarette smoking (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, lung cancer) and the potential crosstalk between these health outcomes. Given that racial/ethnic disparities in health, especially as they relate to mental health and addiction, are complex and multifactorial phenomena, additional research is required to better understand the psychosocial mechanisms underlying these racial differences. This knowledge may potentially lead to the design and implementation of more effective strategies for prevention and treatment tailored to the specific needs and characteristics of each racial/ethnic group.

Authors Contribution

M.F. originated the study idea and formulated the research questions. J.C.H. and L.L. provided feedback on the concept and rationale of the study. J.C.H. and M.F. developed the data analysis plan and conducted the statistical analyses. E.H.M., K.C. and L.L. contributed to development and revision of the data analysis plan. J.C.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. M.F. contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. E.H.M., M.L.F., S.A., K.C. and L.L. provided critical feedback and contributed to interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript, provided feedback and approved the final submission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the clinical and research staff involved in data collection, patient care and clinical/technical support at the NIAAA Clinical Program, in particular the NIAAA Office of Clinical Director (OCD), and at the NIH Clinical Center, in particular the Department of Nursing. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the participants who took part in this study.

Contributor Information

Julia C Harris, Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, Translational Addiction Medicine Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore and Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Department of Psychology, College of Arts and Sciences, American University, Washington, D.C. 20016, USA.

Ethan H Mereish, Department of Health Studies, College of Arts and Sciences, American University, Washington, D.C. 20016, USA.

Monica L Faulkner, Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, Translational Addiction Medicine Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore and Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Shervin Assari, Department of Family Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA 90059, USA.

Kelvin Choi, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Lorenzo Leggio, Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, Translational Addiction Medicine Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore and Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Center on Compulsive Behaviors, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Medication Development Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA; Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02906, USA; Division of Addiction Medicine, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; Department of Neuroscience, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20057, USA.

Mehdi Farokhnia, Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, Translational Addiction Medicine Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore and Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Center on Compulsive Behaviors, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by (A) William G. Coleman Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Innovation Award (PIs: M.F. and M.L.F.), funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) Division of Intramural Research (DIR); (B) National Institutes of Health (NIH) intramural funding ZIA-DA000635 and ZIA-AA000218 (Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, PI: L.L.), jointly funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and (C) NIAAA K08AA025011 grant (PI: E.H.M.). The funding organizations did not have any role in the study design, execution or interpretation of the results. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Abrams DB, Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, et al. (1992) Smoking and treatment outcome for alcoholics: effects on coping skills, urge to drink, and drinking rates. Behav Ther 23:283–97. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, et al. (1997) A review of research on the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21:613–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, et al. (2017) Quitting smoking among adults-United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley KM, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, et al. (2018) Racial/ethnic differences in the association between alcohol use and mortality among men living with HIV. Addict Sci Clin Pract 13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Wu LT (2009) The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17:237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, BrownTaylor D, Guzmán-Becerra N, et al. (2005) Characteristics of malt liquor beer drinkers in a low-income, racial minority community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:402–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Cohen DA, Farley TA, et al. (2008) Alcohol availability and neighborhood characteristics in Los Angeles, California and southern Louisiana. J Urban Health 85:191–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AN, Kim G (2012) Racial/ethnic differences in prevalence and correlates of binge drinking among older adults. Aging Ment Health 16:208–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton SM, Tiffany ST (1997) The effect of alcohol consumption on craving to smoke. Addiction 92:15–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam T (1998) Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: theory and research. Alcohol Health Res World 22:233–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R (2010) Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health 33:152–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H-Y (2004) Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Res Health 28:269–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CMYH, Williams GD, Faden VB. (2009) Surveillance report no. 86: trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991-2007. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance101/Underage13.htm

- Chung T, Pedersen SL, Kim KH, et al. (2014) Racial differences in type of alcoholic beverage consumed during adolescence in the Pittsburgh girls study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLancey JO, Thun MJ, Jemal A, et al. (2008) Recent trends in black-White disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:2908–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden VB (2006) Trends in initiation of alcohol use in the United States 1975 to 2003. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30:1011–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Augustson E, Backinger CL, et al. (2007) Quit attempts and intention to quit cigarette smoking among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 97:1412–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakunle D, Morton CM, Peterson NA (2010) The importance of income in the link between tobacco outlet density and demographics at the tract level of analysis in New Jersey. J Ethn Subst Abuse 9:249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H-y, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2008) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and drug use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Alcohol Res Health 31:100–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores YN, Yee HF Jr, Leng M, et al. (2008) Risk factors for chronic liver disease in blacks, Mexican Americans, and whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999-2004. Am J Gastroenterol 103:2231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D, Marinelli PW, Le AD (2006) Biological processes underlying co-use of alcohol and nicotine: Neuronal mechanisms, cross-tolerance, and genetic factors. Alcohol Res Health 29:186–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Caetano R (2003) Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Res Health 27:87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain D, McCarthy M, Wakefield M (2010) Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiction 105:159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman DM, Speer PW (1997) The concentration of liquor outlets in an economically disadvantaged city in the northeastern United States. Subst Use Misuse 32:2033–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiat 72:757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. (2004) Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61:1107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Verges A, Jackson KM, et al. (2012) Age and ethnic differences in the onset, persistence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder. Addiction 107:756–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW, Treno AJ (2002) Outlets, drinking and driving: a multilevel analysis of availability. J Stud Alcohol 63:460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. (2006) Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med 354:333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, et al. (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:830–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, et al. (2008) Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Prev Med 47:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, et al. (2010) A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics 126:232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JY, Elo IT (2013) The contribution of smoking to black-white differences in U.S. mortality. Demography 50:545–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holford TR, Levy DT, Meza R (2016) Comparison of smoking history patterns among African American and White cohorts in the United States born 1890 to 1990. Nicotine Tob Res 18:S16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe KJ (2013) Neighborhood disadvantage, high alcohol content beverage consumption, drinking norms, and drinking consequences: a mediation analysis. J Urban Health 90:667–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, McKee P, Hannan P, et al. (2008) Alcohol and malt liquor availability and promotion and homicide in inner cities. Subst Use Misuse 43:159–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kiros G-E, Schaffran C, et al. (2004) Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health 94:128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, McNamara P, Conrad M, et al. (2009) Alcohol-induced increases in smoking behavior for nicotinized and denicotinized cigarettes in men and women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 207:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM (2005) Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:547–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Polednak A, Bendel RB, et al. (2004) Disparities in smoking cessation between African Americans and whites: 1990-2000. Am J Public Health 94:1965–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo KK, Rossi JS, Schwartz SJ, et al. (2016) Acculturation and cigarette smoking in Hispanic women: a meta-analysis. J Ethn Subst Abuse 15:46–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, McCarthy EM, Faust AH, et al. (2004) Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol’s acute effects in men. Drug Alcohol Depend 75:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA, Wallace JM Jr (2000) Health risk and inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhood. Soc Sci Med 51:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws MB, Whitman J, Bowser DM, et al. (2002) Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing in demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control 11:ii71–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Reingle JM, Tobler AL, et al. (2010) Effects of beverage-specific alcohol consumption on drinking behaviors among urban youth. J Drug Educ 40:265–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Perez-Stable EJ, Marin BV (1989) Cigarette smoking among San Francisco Hispanics: the role of acculturation and gender. Am J Public Health 79:196–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee P, Jones-Webb R, Hannan P, et al. (2011) Malt liquor marketing in inner cities: the role of neighborhood racial composition. J Ethn Subst Abuse 10:24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Witbrodt J, et al. (2017) Racial/ethnic differences in 30-year trajectories of heavy drinking in a nationally representative U.S. sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 170:133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, et al. (2009) Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:654–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK (2000) The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. J Stud Alcohol 61:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, et al. (1988) Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. J Abnorm Psychol 97:133–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSDUH (2018) 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Table 2.1B—Tobacco Product and Alcohol Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 12 or Older, by Age Group: Percentages, 2017 and 2018. Rockville, MD, USA: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG (1998) Alcohol use among adolescents. Alcohol Health Res World 22:85–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC (2008) Racial convergence in cigarette use from adolescence to the mid-thirties. J Health Soc Behav 49:484–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P 3rd, et al. (1998) Nicotine metabolism and intake in black and white smokers. JAMA 280:152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, McCarthy DE, Fiore MC, et al. (2008) Alcohol consumption, smoking urge, and the reinforcing effects of cigarettes: an ecological study. Psychol Addict Behav 22:230–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polednak AP (2007) Secular trend in U.S. black-white disparities in selected alcohol-related cancer incidence rates. Alcohol Alcohol 42:125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Colby SM, Lu B, et al. (2016) Understanding tobacco use onset among African Americans. Nicotine Tob Res 18:S49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriquez EJ, Fernández A, Livaudais-Toman JC, et al. (2019) How does acculturation influence smoking behavior among Latinos? The role of education and National Background. Ethn Dis 29:227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG, Boardman JD, Pendergast PM, et al. (2015) Drinking problems and mortality risk in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend 151:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo D, Purohit V, Foudin L, et al. (2004) Workshop on alcohol use and health disparities 2002: a call to arms. Alcohol 32:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, Lê Cook B (2013) Blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to complete addiction treatment, largely due to socioeconomic factors. Health Aff (Millwood) 32:135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2007) 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Detailed Tables, Tobacco Product and Alcohol Use, Table 2.46B [Article Online], 2008c. Rockville, MD, USA: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- SAMHSA . (2016) Binge Drinking: Terminology and Patterns of Use, 2016. Rockville, MD, USA: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Samokhvalov AV, Popova S, Room R, et al. (2010) Disability associated with alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1871–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Gordon NP, Weisner C (2007) Alcohol consumption, medical conditions, and health behavior in older adults. Am J Health Behav 31:238–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Martin CS, Wertz JM, et al. (2005) The effects of alcohol on cigarette craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Psychol Addict Behav 19:263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA (2013) Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008-2010. Vital Health Stat 10:1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonlau M, Scribner R, Farley TA, et al. (2008) Alcohol outlet density and alcohol consumption in Los Angeles county and southern Louisiana. Geospat Health 3:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, et al. (2007) Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend 91:159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M, Singh GK, Jones PR, et al. (2010) Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 tobacco use supplement of the current population survey. J Public Health (Oxf) 32:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ (1982) Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol 43:1157–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, et al. (2014) Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 11:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA (1990) Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol 45:921–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA, White MM, et al. (2005) Why does adult African-American smoking prevalence in California remain higher than for non-Hispanic whites? Ethn Dis 15:505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, Emery SL, et al. (2009) Intermittent and light daily smoking across racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 11:203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, White MM, et al. (2011) A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health 101:699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong KD, Sturm R (2007) Alcohol outlets and problem drinking among adults in California. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68:923–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Tai E, et al. (2012) Racial and regional disparities in lung cancer incidence. Cancer 118:1910–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS (1998) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- USDHHS (2014) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Vaeth PA, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R (2017) Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among U.S. racial/ethnic groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:6–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, McKee SA (2017) An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 43:186–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade J, Peralta RL (2017) Perceived racial discrimination, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol abstinence among African American and White college students. J Ethn Subst Abuse 16:165–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD (2017) Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: a representative sample of the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 180:204–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2014) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. p. XIII. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 [Google Scholar]

- Widome R, Brock B, Noble P, et al. (2013) The relationship of neighborhood demographic characteristics to point-of-sale tobacco advertising and marketing. Ethn Health 18:136–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, et al. (2014) Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:1662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.