Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines racial and ethnic disparities in estimated excess deaths from homicide, suicide, transportation, and drug overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected racial and ethnic minority groups in the US.1 However, estimating the full effects of the pandemic on health disparities should account for other causes of death, including external causes.2 We estimated racial and ethnic disparities in excess deaths from external causes (homicide, suicide, transportation, and drug overdoses) from March through December 2020.

Methods

We obtained monthly death data from the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After identifying external causes of death with the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes, we fitted dynamic harmonic regression models to monthly death count data from January 2015 to February 2020 to forecast deaths from March to December 2020 (eTable in the Supplement).3 We estimated excess deaths and the 95% prediction intervals (PIs) by subtracting the number of forecasted deaths from the number of observed deaths. Race and ethnicity data obtained from death certificates included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and White. Because the study used publicly available, deidentified data on deceased individuals, it was not submitted for human participants review, consistent with guidance from the Stanford University institutional review board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Results

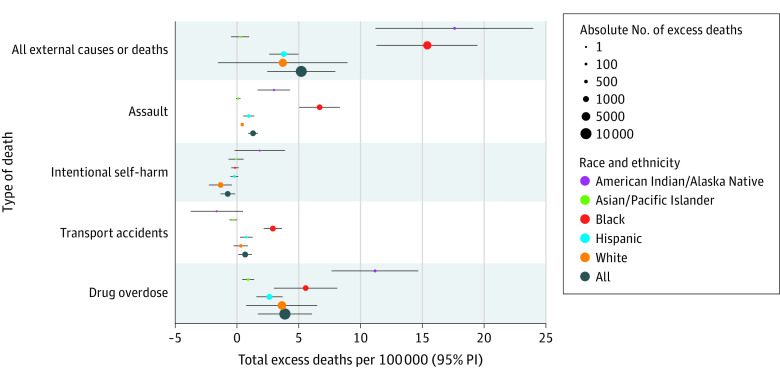

Between March and December 2020, we estimated 17 251 (95% PI, 8114-26 245), excess deaths from all external causes occurred in the US, corresponding to 5.24 (95% PI, 2.46-7.97) estimated excess deaths per 100 000 individuals. Estimated excess deaths were primarily attributable to homicides, drug overdoses, and transportation fatalities (Figure).

Figure. Total Estimated Excess Deaths per 100 000 Population by Race and Ethnicity and Types of External Causes of Death Between March and December 2020 in the US.

Total excess deaths were calculated by summing up excess deaths between March and December 2020. All external causes of deaths include transportation fatalities, other external causes of unintentional injury, suicide, homicide, event of undetermined intent, legal intervention and operation of war, complication of medical and surgical care, and sequelae of external causes of morbidity and mortality. PI Indicates prediction interval.

Estimated excess death rates from all external causes were highest among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals (17.66 per 100 000 population; 95% PI, 11.21-23.98) and Black individuals (15.41 per 100 000 population; 95% PI, 11.29-19.46), and lowest among Asian or Pacific Islander individuals (0.27 per 100 000 population; 95% PI, –0.47 to 1.00) (Table).

Table. Estimated Excess Deaths From External Causes, by Race and Ethnicity in the US, March Through December 2020a.

| Death type | Observed (expected) deaths March to December, 2020 | (95% PI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated excess deaths | Observed to expected ratio | |||

| March to December, 2020 | Per 100 000 population | |||

| All external causes of deaths | ||||

| All | 241 566 (224 315) | 17 251 (8114 to 26 245) | 5.24 (2.46 to 7.97) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.12) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3379 (2890) | 489 (310 to 663) | 17.66 (11.21 to 23.98) | 1.17 (1.1 to 1.24) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5126 (5068) | 58 (–101 to 213) | 0.27 (–0.47 to 1) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) |

| Black or African American | 42 066 (35 343) | 6723 (4924 to 8488) | 15.41 (11.29 to 19.46) | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.25) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 28 091 (25 753) | 2338 (1599 to 3063) | 3.81 (2.61 to 5) | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.12) |

| White | 162 104 (154 552) | 7552 (–3086 to 17 989) | 3.77 (–1.54 to 8.97) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) |

| Homicide | ||||

| All | 21 225 (16 893) | 4332 (3028 to 5616) | 1.31 (0.92 to 1.7) | 1.26 (1.17 to 1.36) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 330 (247) | 83 (46 to 120) | 3.02 (1.68 to 4.32) | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.57) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 310 (285) | 25 (–10 to 59) | 0.12 (–0.05 to 0.28) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.24) |

| Black or African American | 11 889 (8967) | 2922 (2198 to 3634) | 6.7 (5.04 to 8.33) | 1.33 (1.23 to 1.44) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3341 (2747) | 594 (318 to 865) | 0.97 (0.52 to 1.41) | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.35) |

| White | 5315 (4463) | 852 (522 to 1176) | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.59) | 1.19 (1.11 to 1.28) |

| Suicide | ||||

| All | 38 268 (40 690) | –2422 (–4371 to –502) | –0.74 (–1.33 to –0.15) | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 576 (524) | 52 (–5 to 108) | 1.88 (–0.19 to 3.90) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1264 (1277) | –13 (–143 to 115) | –0.06 (–0.67 to 0.54) | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.10) |

| Black or African American | 2844 (2909) | –65 (–198 to 64) | –0.15 (–0.45 to 0.15) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3828 (3953) | –125 (–317 to 63) | –0.2 (–0.52 to 0.10) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) |

| White | 29 666 (32 309) | –2643 (–4517 to –796) | –1.32 (–2.25 to –0.4) | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.97) |

| Transportation fatalities | ||||

| All | 38 354 (36 135) | 2219 (410 to 4001) | 0.67 (0.12 to 1.21) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 625 (670) | –45 (–103 to 14) | –1.62 (–3.74 to 0.49) | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.02) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 805 (867) | –62 (–126 to 1) | –0.29 (–0.59 to 0.01) | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.00) |

| Black or African American | 7219 (5945) | 1274 (948 to 1594) | 2.92 (2.17 to 3.65) | 1.21 (1.15 to 1.28) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6210 (5742) | 468 (154 to 774) | 0.76 (0.25 to 1.26) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.14) |

| White | 23 431 (22 809) | 622 (–539 to 1766) | 0.31 (–0.27 to 0.88) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) |

| Drug overdose | ||||

| All | 78 921 (66 021) | 12 900 (5618 to 20 043) | 3.92 (1.71 to 6.08) | 1.2 (1.08 to 1.34) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 986 (676) | 310 (212 to 406) | 11.21 (7.67 to 14.69) | 1.46 (1.27 to 1.70) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1053 (858) | 195 (91 to 297) | 0.92 (0.43 to 1.40) | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.39) |

| Black or African American | 13 445 (11 009) | 2436 (1307 to 3546) | 5.59 (3.00 to 8.13) | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.36) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9183 (7567) | 1616 (960 to 2262) | 2.64 (1.57 to 3.69) | 1.21 (1.12 to 1.33) |

| White | 53 791 (46 457) | 7334 (1518 to 13 040) | 3.66 (0.76 to 6.50) | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.32) |

Abbreviation: PI, prediction interval.

Observed to expected ratios were defined as the observed number of deaths divided by the expected number of deaths. All external causes of deaths included transportation fatalities, other external causes of unintentional injury, suicide, homicide, event of undetermined intent, legal intervention and operation of war, complication of medical and surgical care, and sequelae of external causes of morbidity and mortality.

Black individuals had the highest estimated excess homicide deaths per capita (6.7 per 100 000 population; 95% PI, 5.04-8.33)—more than twice the next highest group (American Indian or Alaska Native individuals (3.02; 95% PI, 1.68-4.32).

Lower than expected suicide deaths primarily reflected patterns among White individuals (−2643 estimated excess deaths; 95% PI, –4517 to –796).

Although all groups had estimated excess deaths from drug overdose, American Indian or Alaska Native individuals had the highest per capita estimated excess deaths (11.21 per 100 000 population; 95% PI, 7.67-14.69).

Excess transportation fatalities were only evident among Black individuals (1274 estimated excess deaths; 95% PI, 948-1594) and Hispanic individuals (468 excess deaths; 95% PI, 154-774).

Discussion

This study found racial and ethnic disparities in estimated excess deaths from external causes during the COVID-19 pandemic and our findings suggest that the pandemic contributed to these disparities through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Structural racism is the fundamental cause of observed disparities in excess deaths from external causes in the US.4 Discrimination against Black and American Indian or Alaska Native populations has left these communities especially vulnerable to the consequences of the pandemic, including worsening poverty, unemployment, housing instability, food insecurity, and decreased access to health care. For instance, structural barriers to accessing treatment services and lower-burden medications such as buprenorphine may have contributed to drug overdoses in minority communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, riskier driving increased2; which, combined with differences in occupations and the ability to work from home,5 may be associated with higher rates of transportation fatalities in the Black population. Limitations of this study include inaccurate death certificates and untestable modeling assumptions. In addition, the aggregated data did not allow us to evaluate differences between Asian or Pacific Islander subgroups, which have been documented for other health outcomes and may have been exacerbated with recent increases in anti-Asian racism in the US.6 These results underscore the urgency of addressing the structural determinants of violence, substance use, and transportation deaths among racial and ethnic minority groups, especially among Black and American Indian or Alaska Native communities.

eTable. Underlying Causes of Death with ICD-10 Codes

References

- 1.Alcendor DJ. Racial disparities-associated COVID-19 mortality among minority populations in the US. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2442. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faust JS, Du C, Mayes KD, et al. Mortality from drug overdoses, homicides, unintentional injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and suicides during the pandemic, March-August 2020. JAMA. 2021;326(1):84-86. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YH, Glymour MM, Catalano R, et al. Excess mortality in california during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, march to august 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):705-707. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How Structural Racism Works—Racist Policies as a Root Cause of US Racial Health Inequities. Mass Medical Soc; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YH, Glymour M, Riley A, et al. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18-65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through November 2020. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalyanaraman Marcello R, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. Disaggregating Asian race reveals COVID-19 disparities among Asian American patients at New York City’s public hospital system. Public Health Rep. 2022;137(2):317-325. doi: 10.1177/00333549211061313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Underlying Causes of Death with ICD-10 Codes