Abstract

This comparative effectiveness research study evaluates the association between toy type and parent language input during play with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and those with typical development.

Although structural language skills (eg, vocabulary) are no longer part of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), many children with ASD have severe language delays that limit their social and academic success.1 Parent-child play is critical for supporting language development in children with ASD.2 Parents and caregivers are commonly taught to create high-quality play interactions by responding promptly and contingently, following the child’s lead, and providing rich language input.2 However, toy type can affect the richness of these interactions and the learning opportunities they provide.

Electronic toys have become increasingly prevalent compared with traditional, nontechnologically advanced toys. Though often marketed as educational, electronic toys may compromise the quality of play interactions.3,4,5 Clinicians should provide evidence-based recommendations about toy selection to parents of children with ASD, but existing studies focus exclusively on children with typical development (TD). The goal of this study was to test the association between toy type and parent language input provided to children with and without ASD. We hypothesized that input quality and quantity would be lower during electronic vs traditional toy play across groups.

Methods

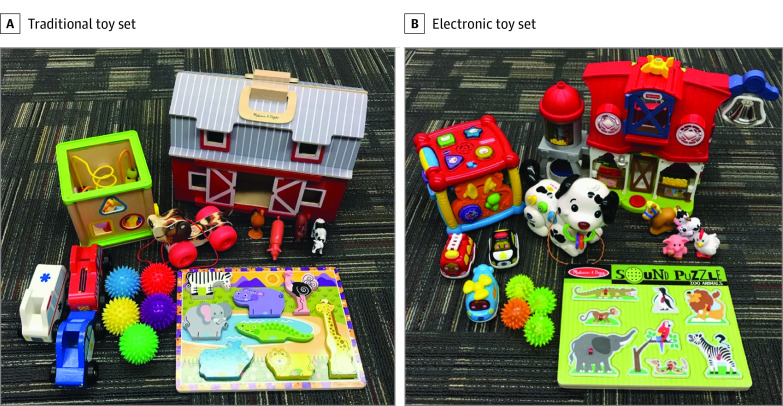

In this comparative effectiveness research study, data were collected from January 1, 2018, to March 15, 2020. Families completed 2 laboratory visits. Parent-child dyads participated in 1 play session with electronic toys and 1 with traditional toys (Figure) of 10 minutes each. Research assistants transcribed sessions. Details are given in the eMethods in the Supplement. This work received prospective approval by the Michigan State University institutional review board. Parents provided written informed consent. This study followed the ISPOR reporting guideline.

Figure. Traditional Toy Set and Electronic Toy Set.

Number of parent utterances per minute and percentage of pause time represented input quantity. Number of different word roots per minute (measure of lexical diversity) and mean length of parent utterances (measure of grammatical complexity) represented input quality. We analyzed the data using repeated-measures analysis of variance using R, version 3.6.1 (R Project). Alpha was set at .05. Hypothesis tests were 2-sided.

Results

Participants were 14 children with ASD (11 boys, 3 girls) and their mothers and 14 children with TD (5 boys, 9 girls) and their parents (11 mothers, 3 fathers). Mean (SD) age did not differ significantly between the ASD (44 [13] months) and TD (46 [15] months; P = .63) groups. Parents reported child race and ethnicity from investigator-defined options based on categories recommended by the National Institutes of Health (Supplement).

During electronic vs traditional toy play, parents produced significantly fewer utterances (mean [SD], 16.25 [3.83] vs 18.65 [5.98]), a significantly higher percentage of pause time (mean [SD], 24% [19%] vs 16% [19%]), and significantly fewer different word roots per minute (mean [SD], 14.60 [3.20] vs 16.03 [3.37]) (Table). Toy type was not significantly associated with mean length of parent utterances.

Table. Toy Type Comparisons by Groupa.

| Mean (SD) [95% CI] | Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Electronic | Mean difference (95% CI) | F 1,13 | P value | η2 | |

| ASD group | ||||||

| Utterances per minute | 18.65 (5.98) [15.52-21.78] | 16.25 (3.83) [14.24-18.26] | 2.40 (0.35-4.45) | 5.28 | .04b | .29 |

| Percentage of pause time | 16 (19) [6.06-25.94] | 24 (19) [14.55-33.95] | 8.30 (3.20-13.40) | 9.90 | .008b | .43 |

| Different words per minute | 16.03 (3.37) [14.26-17.80] | 14.60 (3.20) [12.92-16.28] | 1.43 (0.25-2.62) | 5.62 | .03b | .30 |

| MLU, morphemesc | 3.46 (0.56) [3.17-3.75] | 3.44 (0.65) [3.10-3.78] | 0.02 (−0.17 to 0.21) | 0.04 | .86 | <.01 |

| TD group | ||||||

| Utterances per minute | 14.81 (4.63) [12.38-17.24] | 12.60 (3.69) [10.67-14.53] | 2.22 (0.52-3.91) | 6.53 | .02b | .33 |

| Percentage of pause time | 9 (9) [4.39-14.13] | 24 (16) [15.55-32.23] | 15 (8.50-20.70) | 21.77 | <.001b | .63 |

| Different words per minute | 20.04 (3.72) [18.09-21.99] | 18.02 (2.64) [16.64-19.40] | 2.02 (0.48-3.56) | 6.62 | .02b | .34 |

| MLU, morphemesc | 4.84 (0.82) [4.41-5.27] | 4.94 (0.42) [4.72-5.16] | 0.10 (−0.22 to 0.42) | 0.37 | .55 | .03 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; MLU, mean length of utterances produced by parents; TD, typical development.

Data analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance.

Significant at P < .05.

Morphemes are words plus grammatical markings.

Discussion

In this study, lower quality and quantity of parent language input for children with and without ASD were associated with electronic toys. Clinicians should advise parents of children with ASD that electronic toys are not necessary for supporting language development and may actually be detrimental. Parents should be assured that they (not the toys) are the most important part of play interactions and that no toy can take the place of an engaged play partner.4,6 Clinicians’ recommendations should take individual beliefs into account to ensure that parents’ efforts to help their children are respected.6

Although the relatively small sample size may limit generalizability, these findings also highlight the benefits of engaging children in play with traditional toys. When parents talk more and provide a more diverse vocabulary, children gain opportunities to learn language and how to communicate in a flexible way. This concept is particularly important for interventions that teach parents to maximize the quality and quantity of their language input, as the use of traditional toys may best support this goal.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods Information

References

- 1.Ellis Weismer S, Kover ST. Preschool language variation, growth, and predictors in children on the autism spectrum. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(12):1327-1337. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman HM. How young children learn language and speech. Pediatr Rev. 2019;40(8):398-411. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sosa AV. Association of the type of toy used during play with the quantity and quality of parent-infant communication. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(2):132-137. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wooldridge MB, Shapka J. Playing with technology: Mother–toddler interaction scores lower during play with electronic toys. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2012;33:211-218. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zosh JM, Verdine BN, Filipowicz A, Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Newcombe NS. Talking shape: parental language with electronic versus traditional shape sorters. Mind Brain Educ. 2015;9(3):136-144. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassinger-Das B, Quinones A, DiFlorio C, et al. Looking deeper into the toy box: understanding caregiver toy selection decisions. Infant Behav Dev. 2021;62(January):101529. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods Information