Abstract

The main purpose of this study is to gain an in‐depth understanding of the impact of financial prudence (FIN) on social influence and environmental satisfaction in the sustainable consumption (SC) behavioural model from a cross‐market intergenerational perspective in the context of COVID‐19. Surprisingly, we discovered that, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, significant differences emerge between the Chinese and European markets in the four factors (social influence, SC behaviour, environmental satisfaction, and FIN). Unpredictably, Generation X in the European market and Generation Y in the Chinese market had the highest FIN during the pandemic. Another substantial contribution is that, during the epidemic, the influence of social interaction promotes SC behaviour and social influence motivates users to implement SC behaviours by enhancing environmental satisfaction. However, differences arise in the moderating effect of FIN. In China, the moderating effect occurs in the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour, whereas, in Europe, it reflects in the relationship between social influence and environmental satisfaction.

Keywords: consumer behaviour, COVID‐19, crisis, environmental satisfaction, financial prudence, intergenerational theory, social influence, sustainable consumption

1. INTRODUCTION

The study of sustainable development has captured attention since the 1970s, but only in 2015 did sustainable consumption (SC) and production become the goal of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which requires governments, international organisations, the business sector, and other non‐state actors and individuals to contribute to changing unsustainable consumption (UNEP, 2002; United Nations, 2015). The global outbreak of the coronavirus in 2019 (COVID‐19) has caused governments, enterprises, and individuals in various countries to pay even more attention to the issue of sustainable development. The COVID‐19 pandemic had serious the impacts on all 17 goals (United Nations, 2020). Consumer behaviour has changed radically in response to COVID‐19 in every aspect of their lives (Fabius et al., 2020). In June 2020, the European Union launched a seminar called ‘Towards an EU Strategy on SC after COVID‐19’, which asked for more scholars and experts to analyse the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on SC. Moreover, preventing excessive consumption and wasting resources is an important driving force in the development of SC. Excessive consumption is a key contributor to being environmental, unsustainable, and causing social harm (Hume, 2010). In 2019, consumers globally tossed away nearly a billion tonnes of food, which is the equivalent of 17% of food consumption (UNEP, 2021). This widespread food waste reflects a prevalent lifestyle based on having abundant resources, a view which is ripe for deconstruction due to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Cohen, 2020). With the advent of big data, artificial intelligence, and the sharing economy, the pressure for more sustainable development, the methods of production, and service delivery have changed, further promoting SC behaviour by the general public (Farooq Baqal & Abdulkhaleq, 2018; Chi et al., 2020; Zhen & Xu, 2019). Moreover, companies considering investments in CSR (corporate social responsibility) are advised to focus more on SC and production (Poddar et al., 2019) and to increase organisational trust and identification. Especially in culturally plural organisations (Lissillour & Wang, 2021), organisational trust and identification play an important role in the impact of CSR on employee green behaviour (May et al., 2021).

SC behaviour is a result of conflicting objectives in purchasing decisions, but the combined influence of non‐environmentally related factors have not yet been explored (Testa et al., 2020). As many researchers have found contrasting results for SC in the environmental dimension, Balderjahn et al. (2013) and Dangelico et al. (2021) strongly encourage cross‐country comparisons of environmental consumer behaviour. Future research on the environmental dimension of sustainable development should deepen understanding of the motivations that drive green consumption (Hojnik et al., 2020). Contrasting results on the impact of social influence on pro‐environmental behaviour (PEB) led Alzubaidi et al. (2021) to call for research examining contextual factors that might influence consumer intentions to adopt PEBs. According to Lazaric et al. (2019), future research could explore in more depth the weight of the regional context in the impact of social influence on environmental awareness and SC. Because the financial dimension of SC behaviour dominates the environmental dimension, further research should investigate more thoroughly the conditions in which consumers behave in a way that is more environmentally friendly (Jaeger‐Erben et al., 2021). Furthermore, Liu et al. (2020) suggest that research should focus on motives that continuously engage participants in the process of giving and receiving used goods as an example of consumer satisfaction. The giving and receiving of used goods fully support the idea of SC. Chang and Chuang (2021) have been calling for more research on consumers' recognition of cheaper alternative products and services, consumers' attitude towards social, environmental, and ecological concerns and their motifs towards environmental and social benefits. Moreover, Ramkumar et al. (2021), who studied consumer perception towards circular fashion services, suggest the further investigation of stakeholder engagement in products and services resulting from the circular economy. Therefore, increasing calls for research led us to investigate the relationship between different variables of SC (FIN, social influence, environmental satisfaction) across geographic areas and across generations.

The main purpose of this study is to gain an in‐depth understanding of the impact of FIN on social influence and environmental satisfaction in the SC behavioural model from a cross‐country intergenerational perspective in the context of COVID‐19.

The current study makes several contributions to the literature. First, many studies do not employ a systematic approach to SC that is grounded in an integration of social, environmental, and economic characteristics (Balderjahn et al., 2013; Phipps et al., 2013; Piligrimienė et al., 2020). Mindful consumption is a customer‐centric approach to sustainability that considers the interdependence of a consumer's environmental, personal, and economic well‐being (Sheth et al., 2011). Only a few studies have investigated the relationship between all three main dimensions of SC (Balderjahn et al., 2013; Geiger et al., 2018; Gleim, Smith, Andrews, & Cronin, 2013; Ozaki & Sevastyanova, 2011; Phipps et al., 2013). Outside of the field of SC, the field of CSR could also serve as a generator of value for consumers (Currás‐Pérez et al., 2018) and provide researchers with additional idea about social, environmental and economic dimensions that play a key role in consumers' decision‐making process. CSR practices may also shape consumer's purchasing behaviour where environmental protection looks the most influential with mediating role of consumers´ trust (Tian et al., 2020). We build on these studies, studies focused on the social and the environmental dimensions of SC (Jansson et al., 2017; Quoquab et al., 2019; Shao et al., 2017; Ionescu, 2020; Testa et al., 2020), and studies calling for further research in analysing the position of three modified dimensions in sustainable consumer behaviour.

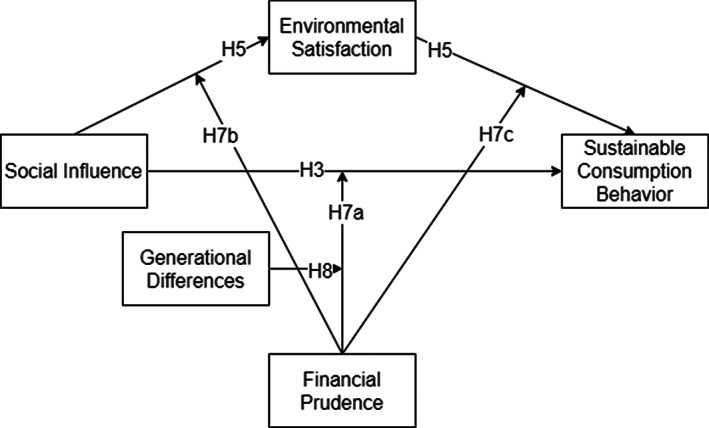

Second, this study makes another contribution to the existing literature by proposing a model of SC in which FIN (Bakar et al., 2020; Hibbert et al., 2004; Yuesti et al., 2020) plays a moderating role by influencing the relation between social influence (Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2011; Lazaric et al., 2019; Rashotte, 2007) and environmental satisfaction (Chen et al., 2019) and between social influence and sustainable consumer behaviour.

We test our research model, avoiding the most common limitations, such as geographic limitations, small sample size limitations, or a focus on a specific generation. This study is based on a sample of 3771 consumers in Europe and China and compares SC across four generations (Gen Z, Gen Y, Gen X, and baby boomers).

Finally, we study the roles of social influence, environmental satisfaction, and FIN in SC by consumers who did and did not change their consumption patterns during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The paper is structured as follows. First, a literature review on the factors affecting SC is presented, organised into sections on SC, intergenerational and intercultural perspectives on SC, and social influence, environmental satisfaction, and FIN. Next, a conceptual framework with hypotheses is outlined in the methodological section, including the sample, operationalisation of variables, and analytical methods. Afterwards, we present the research results and discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our framework. Finally, we highlight the main conclusions and limitations and suggest possible avenues for future research.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

2.1. SC in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic

SC was first proposed at the UN Environment Programme's Oslo Symposium in 1994. It was then defined as ‘the use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimising the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardise the needs of further generations’ (Ministry of the Environment Norway, 1994). Subsequently, many scholars of SC have enriched and expanded this definition by adding the issues of a consumer's quality of life, product life cycle, and protection of resources and the environment. See Table 1 on the evolution and development of the concept of SC.

TABLE 1.

Development and evolution of the concept of sustainable consumption

| Year | Publisher/authors | Concept | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 |

Oslo Symposium on Sustainable Consumption hosted by the Norwegian government (Ministry of Environment Norway, 1994) |

The use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and enable a better quality of life, while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials, and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations. | Intergenerational issues, production, and consumption |

| 1997 |

Jiadong Yang & Xingfang Qin (Yang & Qin, 1997) |

Consumption that conforms to the principles of inter‐generational justice and intra‐generational justice, which can ensure the continuous evolution of human material and spiritual life from a low to a high level and promote the achievement of sustainable development strategies. | Development of material and spiritual life |

| 2000 |

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)/Carl Duisberg Gesellschaft (UNEP/CDG, 2000) |

Sustainable consumption is not about consuming less but about consuming differently, consuming efficiently, and having an improved quality of life | Efficiency and quality |

| 2002 |

Global Status Report issued by UNEP (UNEP,2002) |

Six strategic areas to develop sustainable consumption:

|

Concept development, measurement, and the transformation of products and services |

| 2005 |

Mette Wier, Line Block Christoffersen, Trine S. Jensen, Ole G. Pedersen, Hans Keiding, & Jesper Munksgaard (Wier et al., 2005) |

Human consumption behaviour and its impact on the environment; resources can be reflected in the direct and indirect impacts of the family‐centric social unit on the environment. | The impact of households on sustainable consumer behaviour |

| 2010 |

William Young, Kumju Hwang, Seonaidh McDonald, & Caroline J. Oates (Young et al., 2010) |

In the same broad sense as ‘green’, ‘environmental’, and ‘ethical’ consumption, these consumers prefer products or services that do the least harm to the environment, as well as those that support forms of social justice. | Social factors |

| 2012 |

Catherine Banbury, Robert Stinerock, & Saroja Subrahmanyan (Banbury et al., 2012) |

The concept of SC implicitly assumes that individual choices, lifestyles, and behaviour would significantly lower resource use through efficient market mechanism | individual choices, lifestyles, and behaviour |

| 2012 |

Xuebing Dong, Zhi Yang, & Ying Li (Dong et al., 2012) |

Sustainable consumption is an important manifestation of achieving sustainable development, including sustainable production and consumption (abbreviated as ‘sustainable production behaviour’) and sustainable living consumption (abbreviated as ‘sustainable consumption behaviour’). | Sustainable consumption is divided into two dimensions: production and life |

| 2015 |

Jianping Zhang, Jianjun Ji, & Jing Jin (Jianping et al., 2015) |

Compared with traditional consumption patterns, sustainable consumption patterns have three important connotations: economic sustainability of consumption patterns, environmental sustainability of consumption patterns, and social sustainability of consumption patterns. | Contrast with traditional consumption methods and emphasise the uniqueness of sustainable consumption in China |

| 2019 |

Yang Zhen & Yingjie Xu (Zhen & Xu, 2019) |

In the context of the sharing economy, the ethical core of sustainable consumption is embodied in the efficient aggregation of idle resources on a shared platform, enabling consumers and suppliers to achieve precise docking, and achieving intra‐generational and inter‐generational fairness in consumption. In addition, the separation of product ownership and use rights under the sharing economy promotes the sustainability of the consumption process. Furthermore, the value creation process based on collaboration and co‐creation implements the consumer's concept of sustainable consumption. |

Consumption ethics, consumption process, and sharing economy |

Before the outbreak of COVID‐19, the main hot topics discussed in the study of SC behaviour included the classification and development of the concept of SC behaviour (Belz & Peattie, 2009; Dong et al., 2012; Liu, 2016; Yang & Qin, 1997) and the influence of social structural factors (Li & Li, 2017; Zhou & Shen, 2020) and psychological factors (Sidique et al., 2010; Thøgersen & Ölander, 2002), and other external intervention factors (Egmond et al., 2006; Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2011; Xie & Liu, 2018) on SC behaviour as well as research on the impact of shared or second‐hand products on SC in emerging markets (Liu et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2020; Zhen & Xu, 2019). However, the COVID‐19 pandemic interrupted progress towards attaining the sustainable development goals (Perkins et al., 2021). The impact of the awareness of SC on behaviour became the prevalent topic (He & Liu, 2021; Severo et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). The research on supply chain management of SC and technological innovation (Kumar et al., 2020; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al., 2020) in this period attracted attention. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, new consumption patterns and lifestyles have stimulated consumers to engage in SC (Degli Esposti et al., 2021). Therefore, the COVID‐19 pandemic can be used as a catalytic event to enhance people's SC behaviour, from the macro‐level political (e.g., economic and cultural aspects) (Wells et al., 2020) to the micro level, such as personal lifestyle (Echegaray, 2021).

In conclusion, research on the concept and influencing factors of SC behaviour is becoming more comprehensive, but there is still room for research to explore the changes during COVID‐19, notably in terms of generational theory, environmental satisfaction, and FIN.

2.2. Intergenerational perspectives on SC

Mannheim (1970) believes that the modes of thinking and values of different generational groups are influenced by social, historical, and political factors, which result in significant behavioural differences. Therefore, when consumption behaviour is studied, it is necessary to analyse the distinct patterns that characterise generational groups. Based on the standards for the classification of intergenerational differences in SC in previous studies (Chaney et al., 2017; Dabija & Bejan, 2018), we use the following classification: the world crisis generation (born before 1946), baby boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), Generation Y (1981–1996), and Generation Z (1997–2012). Are there any intergenerational differences in SC behaviour between China and Europe?

In China, differences in generational consumption are influenced by the concept of intergenerational support. Parents' educational expectations for their children affect the family's ‘downward’ intergenerational support. The expectations of parents of high‐quality education for their children have a significant impact on the consumption expenditure of the next generation (Zhang, 2019). Prior research on differences in intergenerational consumption has explored the differences in intergenerational consumption based on the dynamic monitoring of Chinese migrants and finds that the younger generation has greater consumption potential than prior generations (Wang & Deng, 2021). Affected by the epidemic, older generations became more committed to organic food. Younger generations' attitude towards game meat is more negative, whereas older generations attach more importance to it because of its nutritional and medicinal value (Xie et al., 2020). Moreover, parents' ecological knowledge and consumption behaviour influence their children's green consumption intention (Gong et al., 2020).

In Europe, some scholars have confirmed that Generation Z is more inclined to accept sustainable behaviour than other generations of consumers (Suchanek & Szmelter‐Jarosz, 2019). In France, a study finds that the relationship between perceived consumer effectiveness and the purchasing intention for environmentally responsible products is stronger for Generation X, while media exposure has a bigger impact on Generation Y (Ivanova et al., 2019). Other studies find that Generation Y (millennials) are more enthusiastic about purchasing the right to use (renting or shared use) rather than purchasing ownership (Hwang & Griffiths, 2017).

The pandemic may have changed and affected the consumption patterns of different generations across markets. Currently, Chinese Generation Z pays more attention to factors such as being in tune with nature, social recognition, and patriotism (Growth from Knowledge, 2021). In addition, a global survey of Generations Y and Z finds that the pandemic has brought about an even stronger sense of individual responsibility and that a majority of respondents are financially prudent and literate (Deloitte, 2020). A study on Brazil and Portugal finds that Gen Y felt the impact of the pandemic more than other generations (Severo et al., 2021). Therefore, SC behaviour during COVID‐19 varies across generations and cultures. Thus, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1a

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in sustainable consumption behaviour between Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H1b

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in sustainable consumption behaviour between generations in Chinese and European markets.

2.3. Social influence and changes in SC behaviour during the COVID‐19 pandemic

What is the role of social influence in the transition from SC consciousness to SC behaviour? The characteristic of social influence is that disseminating information causes people to increasingly consider interactions with other individuals or social groups (Rashotte, 2007). Based on the social influence theory put forward by Deutsch and Gerard (1955), social norms and social consensus direct public attention and lead consumers to imitate behavioural intentions (Nolan et al., 2008; Reynolds et al., 2015; Testa et al., 2018). Social influence provides consumers with information and the motivation to form or imitate new attitudes and adopt behaviours that are accredited by the public (Alzubaidi et al., 2021; Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2011). SC as a new behavioural intention or behavioural practice has become an important driving force in the expansion of interpersonal relationships in social communication (Robertson, 1967). In a recent study based on data in Saudi Arabia, consumer intentions were found to have a significant effect on indirect PEBs and direct PEBs (Alzubaidi et al., 2021). Thus, it drives further efficiency in the conversion of SC intention into behaviour (Salazar et al., 2013) in social networks. When consumers become aware of changing or maintaining their patterns of SC, they will be more likely to strengthen their own behavioural tendencies, disseminate related cognitive structures and practical processes, and influence the decisions of others (Froome et al., 2010). In addition, the action intention of opinion leaders and the forerunners of SC transform the behaviour intention into behaviour practice through communication media and the endorsement of their own behaviour practice, which then spreads to the interpersonal network, resulting in more imitation and convergence (Froome et al., 2010). During the pandemic, for example, the rapid growth of short videos changed the way in which Chinese consumers socialised. To attract attention, they started to create advertisements and videos about food waste (eatcast; called chibo in Chinese and mukbang in Korean). Inspired by these videos, China's state‐owned media and social platforms called on people not to overeat and spread public announcements to encourage a reduction in food waste, triggering broad agreement in society (China Daily, 2020). Based on this mutual vision, consumers spontaneously began to pay attention to and practice sustainable food consumption seen in the content of short videos. Neurobehavioural patterns may eventually deliver more specific and multifaceted interpretations of consumers' decision‐making process (Drugău‐Constantin, 2019) because neuroscience provides cutting‐edge ways to assess incongruity in consumer behaviour by evaluating dissimilarities in separate sensitivity throughout areas or structural discrepancies in the brain (Mirică, 2019).So how does the relationship between social influence and SC look nowadays? The research about the social influence on SC behaviour has increased in recent years (Lazaric et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). The most discussed social relationships are those among family, friends, and government authorities. We can observe differences in the relationship between social influence and consumer behaviour among different groups of people. Some studies show that the family is better than the government at promoting sustainable consumer behaviour (Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2011), while other studies confirm that peers (e.g., colleagues, family, and friends) have a positive impact on SC (Salazar et al., 2013). Some experiments analyse the purchasing behaviour of members of different social groups (peers, colleagues, family members, and friends) and find that diverse interpersonal relationships have a different degree of social influence (Lazaric et al., 2019; Severo et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Peer effects are also important in promoting SC and changing the consumption patterns of social groups in France (Lazaric et al., 2019).

Research on the generational relationship between social influence and SC (Confente & Vigolo, 2018) reveals differences in the effects of social influence and attitudes on the online purchasing decisions of four groups (Generation Y, Generation X, baby boomers, and the silent generation (born between 1925 and 1945). Chinese Generation Z is more dependent on social media than other generations in China (Growth from Knowledge, 2021). A study on eight European countries concludes that if the reference group adopts organic food, the other groups might imitate it, and the larger the number of consumers, the greater the social pressure to buy is (De Maya et al., 2011).

However, research on the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour does not take into account the differences between countries and generations at the same time. In addition, the COVID‐19 pandemic has led to tremendous changes in life and work styles towards the increased use of digital channels and technologies (Kannan, 2020; Lazaric et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). The importance of online social networking has become increasingly prominent in SC behaviour (Severo et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis H2a

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence of sustainable consumption behaviour differs between Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H2b

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence of sustainable consumption behaviour differs between generations in Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H3

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence had a positive influence on sustainable consumption behaviour.

2.4. Environmental satisfaction and changes in SC behaviour during the COVID‐19 pandemic

Environmental satisfaction has different conceptual connotations across disciplines but mainly consists of individual responses to the natural environment and to government environmental policies (Chen et al., 2019). In this study, environmental satisfaction refers to consumers' willingness to contribute to protecting the environment and to their satisfaction regarding their environmental responsibility. In recent studies, this phenomenon is called ‘green experience satisfaction’, conceptualised as an important dimension of the relationship between brand quality and consumers (Wu et al., 2018). Education on the concept of sustainability regards environmental protection behaviour as having achieved a social consensus (Wang et al., 2020). Environmental responsibility represents a person's perception of environmentally friendly behaviour, which can significantly increase a customer's willingness to consume sustainably (Liu et al., 2012). So, after the awareness of SC is widely reflected in social norms and public opinion, consumers make product choices by weighing the utility they receive against the ethical behaviour or consensus (environmental satisfaction) expected from certain social groups (Conrad, 2005). Further, researchers have proposed how to promote SC behaviour by influencing consumers' self‐perception. That is when people come to see themselves as ‘consumers willing to make an effort for the sake of the environment’, and their sense of satisfaction in environmental protection increases, which will promote SC behaviour (Cornelissen et al., 2008). Therefore, this paper holds that environmental satisfaction is the bridge between environmental cognition and environmentally friendly behaviour.

Studies on the relationship between environmental cognition and EB have produced a variety of results. Earlier research found that the relationship between cognition and behaviour is not significant or weak (Almeida et al., 2015; Grob, 1995), and new studies believe that it has a significantly positive influence (Wang & Tou, 2021). This may be influenced by the environment, culture, product price, product quality, and other factors. For example, in Brazil, Gen Y scores significantly lower than the other generations in a comparison of environmental awareness in the social networks of baby boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y (Severo et al., 2019). Social influence changes consumers' awareness of SC (Salazar et al., 2013), which in turn is likely to lead to a sense of responsibility, environmental protection, and, consequently, to higher environmental satisfaction (Liu et al., 2012).

The outbreak of the COVID pandemic attracted more attention to environmental problems and influenced consumer behaviour (Butu et al., 2020; Li & Wu, 2020; Sun et al., 2021). A study on Chinese fashion consumers during the pandemic found that those with higher awareness of sustainable fashion felt more moral anxiety (Du et al., 2020). Among the groups of consumers with the highest awareness of sustainable fashion, 74% felt anxious about the negative environmental impact of their consumption. An increasing number of consumers with high awareness of sustainability is practising ‘conscientious consumption’, which means consuming in a way that reduces harm to the environment or supports public welfare (Du et al., 2020). Based on data from the Chinese market, prior research found that a sense of awe about COVID‐19 positively influences green consumption behaviour because those who feel this sense of awe pay more attention to the environment and to society while reinforcing their group identity, thus promoting green consumption (Sun et al., 2021). These consumers paid more attention to their environmental responsibility and environmental contribution, inspiring others to emulate their environmental concern and environmental protection behaviour. Thus, environmental satisfaction drives SC behaviour and influences consumers' decision‐making chains. Based on this reasoning, we propose that:

Hypothesis H4a

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in environmental satisfaction between Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H4b

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in environmental satisfaction between generations in Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H5

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, environmental satisfaction mediates the relationship between social influence and sustainable consumption behaviour.

2.5. Financial prudence and changes in SC behaviour during the COVID‐19 pandemic

The research on finance and SC behaviour focusses on the relationship between consumers' income and SC behaviour. Prior research on consumers' income and SC behaviour led to different and sometimes inconsistent findings because uncontrollable factors measure income as a single indicator. For example, some scholars found that income is an important indicator of decision‐making behaviour that affects households' SC (Di Talia et al., 2019; Sardianou, 2007; Wang et al., 2014), whereas others believe that income has no significant effect on SC behaviour (Feng & Reisner, 2011; Wang & Peng, 2007). Compared to the various impacts of income on financial behaviour (Martin et al., 2006), financial knowledge has a stable and significant impact on short‐ and long‐term financial behaviour (Kim et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2006). Inoescu (2020) focused on studying the relationship between environmental performance, sustainable energy, and green financial behaviour. However, financial knowledge is closely related to social relations. The financial behaviour of parents has a direct positive effect on the financial behaviour of their children (Angulo‐Ruiz & Pergelova, 2015). Parents and peers are likely to significantly influence individuals' financial knowledge and, subsequently, their financial behaviour. There may be differences across generations and cultural backgrounds.

Because of the inconsistency in results based on a single financial indicator, this paper draws on the concept of FIN (Bakar et al., 2020; Hibbert et al., 2004; Voydanoff, 1990; Yuesti et al., 2020). FIN is one of many ways to manage and reduce financial strain (Hibbert et al., 2004). This concept is defined as the acceptance of a degree of caution in the exercise of judgement needed when making required estimations under conditions of uncertainty (Pillai et al., 2010; Voydanoff, 1990). Therefore, we explore the effect of FIN (including financial knowledge, income, and price sensitivity) in the context of the disruption wrought by the pandemic.

Some studies have shown that FIN varies across generations and cultural backgrounds. In research on the Indian market, Generation X engages in more prudent financial behaviours and attitudes than Generation Y (Shobha & Kumar, 2020). Another study based on online consumers also found that Generation X is more cautious than Generation Y in making financial decisions (Tolani et al., 2020). In China, financial attitudes between different generations are influenced by regional and intergenerational support from the previous generation (Zhang, 2019). Moreover, FIN can affect the relationship between social influence and SC behaviours differently, depending on family education or financial socialisation (Bakar et al., 2020; Alekam, 2018; Ivan & Dickson, 2008), as well as on environmental satisfaction and SC behaviour (Chen, 2021; Nassani et al., 2013).

Studies have shown that the main reason that uncertainty leads to unsustainable behaviour is the ‘future component’ because environmental, social, and economic consequences need to be optimised to meet the needs of future generations (van der Wal et al., 2018). Environmental uncertainty increases the FIN of consumers (Pillai et al., 2010) because acting sustainably incurs individual costs (Van der Wal et al., 2016), which will reduce SC behaviour to some extent. Consumer financial behaviour changed during the pandemic. Indeed, a research report based on SC behaviour in the Chinese market over many years found that, in 2018, 77% of consumers did not engage in SC because the price of sustainable goods was higher than that of non‐sustainable products that were similar and thus unaffordable. In 2019, that rate dropped to just 42.95% (SynTao, 2019). In the most recent report, for 2020, the price was the least disruptive factor in moving from SC awareness to SC behaviour (SynTao, 2020). This shows that some consumers are willing to pay a premium within a certain range for sustainable products: for food (Sallandarré et al., 2016; Carley & Yahng, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Galati et al., 2019; Lanfranchi et al., 2019), apparel (Moon & Lee, 2018; Tey et al., 2018) and cars (Costa et al., 2019). At the same time, a recent study based on Chinese microdata concludes that residents affected by the pandemic change their consumption behaviour because of anticipated income reduction, precautionary savings motives, and the tendency towards rational consumption (Li & Wu, 2020). Therefore, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H6a

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence behaviour differs between Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H6b

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence behaviour differs between generations in Chinese and European markets.

Hypothesis H7a

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and sustainable consumption behaviour.

Hypothesis H7b

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and environmental satisfaction.

Hypothesis H7c

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between environmental satisfaction and sustainable consumption behaviour.

Hypothesis H8

Generations moderate the two‐way interaction between social influence and financial prudence on sustainable consumption behaviour.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Sample and data collection

The data collection was performed through conducting a survey of consumers in 13 countries, China plus 12 countries in Europe: Albania, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Macedonia, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, and Ukraine. To ensure the validity of the questionnaire, the research team invited native speakers of various countries to translate it, carried out a back‐translation test in accordance with the questionnaire translation rules, and finally distributed it in 10 national languages. After the translation process, a small number of questionnaires were piloted. After the pilot phase some ambiguous sentences were adjusted and the questionnaires were mainly distributed through online platforms such as Google in Europe, and Wenjuan in China. The survey questions were discussed and repeatedly verified by experts in the field of consumer behaviour or green behavioural research in various countries. The pre‐survey invited 18 people from each group in various countries to participate in the survey. Before distributing the final questionnaire, the response time, wording, and warnings were revised and improved. The questionnaires were distributed in various countries from November to December 2020, and the scenarios were set during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The questionnaire has two main sections. The first section collects demographic variables, including nationality, gender, age, education level, and income level. The age group was screened only from 1946 to 2012, and the income level was based on the official gross national income (GNI) of each country in 2019. The demographic information is shown in Table 2. The second section is the research on SC. A total of 4000 questionnaires were sent out, of which 3771 were valid.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable categories | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Markets | China | 2113 | 56.0 |

| Europe | 1658 | 44.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 1400 | 37.1 |

| Female | 2371 | 62.9 | |

| Generation | Baby Boom (1946–1964) | 245 | 6.5 |

| Generation X (1965–1980) | 698 | 18.5 | |

| Generation Y (1981–1996) | 1287 | 34.1 | |

| Generation Z (1997–2012) | 1541 | 40.9 | |

| Education level | Secondary school or less | 1010 | 26.8 |

| Bachelor's degree | 1793 | 47.5 | |

| Master's degree | 735 | 19.5 | |

| PhD or higher | 233 | 6.2 | |

| Income level | Below national average | 1903 | 50.5 |

| Around national average | 1006 | 26.7 | |

| Above national average | 862 | 22.9 | |

3.2. Measurement scale

The four constructs focused on in this paper are sustainable consumer behaviour (SCB), social impact (SI), environmental (EV) satisfaction, and FIN during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This study is based on previous focus groups and in‐depth interviews with scholars of SC behaviour evaluation and testing. It includes mature items in the literature on SC behaviour and revises them for the context of COVID‐19 to develop the measurement scale used in this study (Table 3). The scale mainly relies on the scales of Joshi and Rahman (2017) in the constructs on SC behaviour, the scales of Wang et al. (2014) and Teoh and Gaur (2019) in the constructs of social influence, the scales of Wu et al. (2018) in the constructs of environmental satisfaction, and the scales of Wang et al. (2014) in the constructs of FIN. These constructs were evaluated with five‐point Likert‐type scales, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

TABLE 3.

Scale measurement items

| Variable | Measurement item | Factor loading | Common factor variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social influence | SI1 | Social aspects in consuming important for me (e.g., to look good, to show your status with a good car or house) | 0.788 | 0.754 |

| SI2 | I would act sustainably if my family and friends do so | 0.642 | 0.749 | |

| SI3 | I am a member of different groups in social media where people donate or sell used products | 0.630 | 0.735 | |

| SI4 | Seeing famous people buy used/second‐hand products or ecological products encourages me in acting in a sustainable way | 0.552 | 0.708 | |

| Environmental satisfaction | EV1 | I am satisfied when I know that I did something for the environment | 0.827 | 0.563 |

| EV2 | I feel good when I donate products that I do not need | 0.838 | 0.581 | |

| EV3 | I feel good when I donate goods, instead of throwing them away | 0.826 | 0.558 | |

| EV4 | Doing something for our planet Earth makes me feel satisfied. | 0.780 | 0.548 | |

| EV5 | I feel good knowing that my purchase behaviour can save the planet as well as my finances | 0.548 | 0.448 | |

| Financial prudence | FIN1 | During the COVID‐19 pandemic, I started to save more money | 0.744 | 0.511 |

| FIN2 | During the COVID‐19 pandemic, I decided to repair products, instead of buying new ones. | 0.664 | 0.640 | |

| FIN3 | During the COVID‐19 pandemic, I will purchase only products within my budget | 0.653 | 0.576 | |

| FIN4 | During the COVID‐19 pandemic, I postponed my investments | 0.637 | 0.511 | |

| FIN5 | During the COVID‐19 pandemic, I think much more than before when spending money. | 0.537 | 0.522 | |

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | SCB1 | When shopping, I choose products with environmentally friendly packaging | 0.781 | 0.515 |

| SCB2 | When shopping, I check the ingredients of the products | 0.734 | 0.724 | |

| SCB3 | Purchase of environmental or eco‐friendly products | 0.668 | 0.614 | |

| Accumulated variance interpretation rate after rotation | 0.601 | |||

| KMO | 0.931 | |||

| Bartlett’s test | chi‐square | 27363.582 | ||

| df | 153.000 | |||

| p | 0.000 | |||

3.3. Research procedure and research model

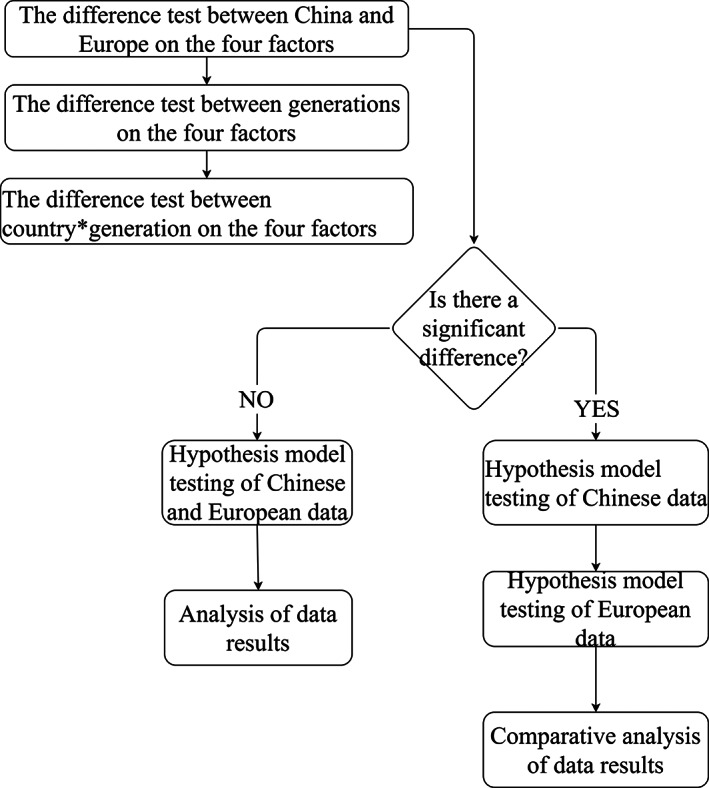

First, we test H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b, H4a, H4b, H6a, and H6b. The purpose is to explore the differences between Chinese and European consumers, different generations, and the interaction between Chinese and European consumers and generations on SI, SC behaviour, environmental satisfaction, and FIN behaviour during the COVID‐19 pandemic. If we find significant differences in the four factors between Chinese and European consumers, then we can further explore whether the differences between Chinese and European consumers in the hypothetical models are significant. First, we discuss the hypothesis and analyse it with data from China and then we conduct a comparative test with the data from Europe. The design process and hypothetical model are shown in Figures 1 and 2. All the hypotheses are listed in Table 4.

FIGURE 1.

Design process

FIGURE 2.

Hypothesis model

TABLE 4.

Tested hypotheses and results

| Hypotheses | Test used | Supported/not supported | Significance level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total data | Chinese data | European data | Total data | Chinese data | European data | ||

| H1a: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in sustainable consumption behaviour between Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | — | — | p < 0.001 | — | — |

| H1b: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in sustainable consumption behaviour between generations in Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | Not supported | Supported | p < 0.001 | p = 0.688 | p < 0.001 |

| H2a: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence of sustainable consumption behaviour differs between Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | — | p < 0.001 | — | ||

| H2b: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence of sustainable consumption behaviour differs between generations in Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | — | — | p < 0.001 | — | — |

| H3: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the social influence had a positive influence on sustainable consumption behaviour. | Linear regression PROCESS Model 4 | — | Supported | Supported | — | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| H4a: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in environmental satisfaction between Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | — | — | p < 0.001 | — | — |

| H4b: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, differences arose in environmental satisfaction between generations in Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Not supported | — | — | p = 0.133 | — | — |

| H5: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, environmental satisfaction mediates the relationship between social influence and sustainable consumption behaviour. | PROCESS Model 4 | Supported | Supported | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||

| H6a: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence behaviour differs between Chinese and European markets. | Two‐way MANOVA | Supported | — | — | p < 0.001 | — | — |

| H6b: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence behaviour differs between generations in Chinese and European markets | Two‐way MANOVA | Not supported | — | — | p = 0.073 | — | — |

| H7a: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and sustainable consumption behaviour. | PROCESS Model 59 | — | Supported | Not supported | p = 0.043 < 0.05 | p = 0.689 | |

| H7b: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and environmental satisfaction. | PROCESS Model 59 | — | Not supported | Supported | p = 0.798 | p = 0.001 < 0.01 | |

| H7c: During the COVID‐19 pandemic, financial prudence has a moderating effect on the relationship between environmental satisfaction and sustainable consumption behaviour. | PROCESS Model 59 | — | Not supported | Not supported | p = 0.529 | p = 0.060 | |

| H8: Generations moderate the two‐way interaction between social influence and financial prudence on sustainable consumption behaviour. | PROCESS Model 12 | Partly supported; supported (except for baby boomers) | — | — | — | — | — |

3.4. Data analysis and measurement model results

3.4.1. Common method bias

We follow the suggestions of Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff et al. (2012), Reio (2010), and Tehseen et al. (2017) to reduce the influence of a common method bias exists. In the survey process, we adopt a series of control measures, such as anonymous decentralised measurement, multi‐source data acquisition, and item order. In each section of the questionnaire, we stress the investigation background of COVID‐19 and relevant guidelines and constructed different variables. In addition, we perform the Harman one‐factor test to identify the first eigenvalue in the data matrix. After some items are deleted, the results of exploratory factor analysis of 18 items show that 4 factors have eigenvalues greater than 1. The first eigenvalue accounts for 37.671% of the total variance (threshold of 50%), indicating that this study is less affected by common method bias and is within an acceptable range (Malhotra et al., 2006; Podsakoff, 2003). The common degree (variance of common factor) values of all items in Table 3 are higher than 0.4, indicating that the research item information can be extracted effectively. Moreover, as shown in Table 5, the absolute values of correlation coefficients between latent variables are all less than 0.9, which also shows that common method variance does not bias our results.

TABLE 5.

Pearson and AVE

| Environmental satisfaction | Sustainable consumption behaviour | Financial prudence | Social influence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental satisfaction | 0.756 | |||

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | 0.570*** | 0.683 | ||

| Financial prudence | 0.464 | 0.529*** | 0.615*** | |

| Social influence | 0.444 | 0.551 | 0.571 | 0.629*** |

Note: Values in italics show the square root of AVE.

3.4.2. Reliability test

Table 6 shows the Cronbach's α coefficient of each factor. SC behaviour comprises four items, with internal consistency reliability of 0.789. The social influence consists of four items, with internal consistency reliability of 0.720. Environmental satisfaction is made up of five items, with internal consistency reliability of 0.871. FIN during the pandemic consists of five items, with internal consistency reliability of 0.755. The Cronbach's α coefficient of each factor is greater than 0.7, indicating that the scale has good reliability, and the measurement items have high reliability and stability.

TABLE 6.

Reliability and validity analysis

| Variable | Cronbach's α | KMO | Bartlett's test | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | 0.789 | 0.773 | Sig. < 0.001 | 0.778 |

| Social influence | 0.720 | 0.753 | Sig. < 0.000 | 0.705 |

| Environmental satisfaction | 0.871 | 0.847 | Sig. < 0.001 | 0.861 |

| Financial prudence | 0.755 | 0.817 | Sig. < 0.001 | 0.749 |

3.4.3. Validity test

First, the factor loading coefficients in Table 3 are all greater than 0.4, which means that a corresponding relationship is found between the item and the factor. Second, the KMO (Kaiser‐Meyer‐Olkin) value is 0.931, and the KMO values of all factors in Table 6 are greater than 0.6, which means that the data are valid. Furthermore, the results of the Bartlett sphere test show that the correlation between variable measurement items is strong, and the validity of the research data is good (Table 6). Finally, the variance interpretation rate values of the four factors are 19.43%, 14.60%, 14.13%, 11.94%, and the cumulative variance interpretation rate after rotation is 60.107% (>50%). This means that the information in the item can be effectively extracted.

We performed an additional CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) test for all factors. In the test of convergent validity, based on the recommendations of Fornell and Larcker (1981), all standardised factor loadings are significant, and the average variance extracted (AVE) of all variables is higher than the standard (0.36–0.5). The composite reliability is greater than 0.70, indicating that each dimension in the scale has good internal consistency. To determine the discriminant validity, we used the same AVE approach and found that the AVE for each pair of factors is higher than their squared correlation (Table 5) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Comparative analysis results between the Chinese and European markets

This paper uses two‐way MANOVA to evaluate the influence of Chinese and European consumers and generations on the four‐factor score. The data are normally distributed in each group (based on the chi‐square, Mahalanobis distance plot, and Shapiro–Wilk test). The Chinese and European markets have significant differences in the four‐factor scores (see Table 7), so H1a, H2a, H4a, and H6a are supported. The difference in the scores for the various generations on FIN (F = 2.326, p = 0.073 > 0.005) and environmental satisfaction (F = 1.865, p = 0.133 > 0.005) during the pandemic was not significant, so H4b and H6b were not supported. However, significant generational differences arise in the scores on SC behaviour (F = 5.957, p = 0.000 < 0.01, η2 p = 0.005) and social influence (F = 29.032, p = 0.000 < 0.001, η2 p = 0.023), which support H1b and H2b. Because the generational group is a categorical variable, we then perform a post hoc comparison to explore the levels of SC behaviour and social influence of the different generational groups. We conduct a pairwise comparison using the Scheffe method, finding that the scores on SC behaviour and social influence are significantly higher for Generations Y and Z than other generational groups.

TABLE 7.

Main effect test

| Variable | F | Eta square | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market (Chinese and European market) | Social influence (H1a) | 647.885*** | 0.147 |

| Environmental satisfaction (H3a) | 32.238*** | 0.008 | |

| Financial prudence (H6a) | 188.167*** | 0.048 | |

| Sustainable consumption behaviour (H8a) | 223.758*** | 0.056 | |

| Generations:baby boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980),Generation Y (1981–1996), Generation Z (1997–2012) | Social influence (H1b) | 29.032*** | 0.023 |

| Environmental satisfaction (H3b) | 1.865 | 0.001 | |

| Financial prudence (H6b) | 2.326 | 0.002 | |

| Sustainable consumption behaviour (H8b) | 5.957*** | 0.005 | |

| Generations* market | Social influence | 3.448* | 0.003 |

| Environmental satisfaction | 2.03 | 0.002 | |

| Financial prudence | 4.288** | 0.003 | |

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | 7.728*** | 0.006 | |

Note: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001.

Table 8 indicates that after adding the environmental satisfaction variables, the R2 increased from 0.400 to 0.506 using Chinese data. Similarly, Table 11 indicates that the R2 increased from 0.140 to 0.238 using European data. The results suggest that environmental satisfaction has a higher influence on SC behaviour in China because the change of R2 in Chinese data (0.106) is higher than the change of R2 in European data (0.098). The same results in the relationship of Social Influence and SC behaviour. Even though Chinese consumers are statistically more influenced, this difference is likely to be explained by their cultural tendency to give higher marks in all items compared to their European counterparts.

TABLE 8.

Results of model 4 based on Chinese data

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | Environmental satisfaction | Sustainable consumption behaviour | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Constant | 0.055 | 0.095 | 0.582 | −0.295** | 0.109 | −2.712 | 0.163 | 0.086 | 1.898 |

| Gender | 0.118*** | 0.031 | 3.819 | 0.257*** | 0.035 | 7.235 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.839 |

| Generations | −0.077*** | 0.019 | −4.036 | −0.077*** | 0.022 | −3.486 | −0.049** | 0.017 | −2.822 |

| Education Level | 0.000 | 0.021 | −0.017 | −0.004 | 0.024 | −0.168 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.060 |

| Income Level | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.967 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.237 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.956 |

| Social Influence | 0.615*** | 0.016 | 37.385 | 0.526*** | 0.019 | 27.808 | 0.422*** | 0.017 | 24.201 |

| Environmental Satisfaction | 0.366*** | 0.017 | 21.324 | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.400 | 0.277 | 0.506 | ||||||

| Adjust R2 | 0.398 | 0.275 | 0.505 | ||||||

| F | F (5, 2107) = 280.608, p = 0.000 | F (5, 2107) = 161.214, p = 0.000 | F (6, 2106) = 359.977, p = 0.000 | ||||||

Note: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001.

TABLE 11.

Results of model 4 based on European data

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | Environmental satisfaction | Sustainable consumption behaviour | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Constant | 0.018 | 0.158 | 0.115 | −0.375* | 0.176 | −2.131 | 0.131 | 0.149 | 0.883 |

| Gender | 0.055 | 0.047 | 1.182 | 0.297*** | 0.052 | 5.72 | −0.035 | 0.044 | −0.784 |

| Generations | −0.036 | 0.025 | −1.422 | −0.042 | 0.028 | −1.508 | −0.023 | 0.024 | −0.969 |

| Education Level | 0.028 | 0.026 | 1.079 | 0.122*** | 0.029 | 4.259 | −0.009 | 0.024 | −0.376 |

| Income Level | −0.089** | 0.032 | −2.769 | −0.056 | 0.036 | −1.569 | −0.072* | 0.03 | −2.377 |

| Social Influence | 0.420*** | 0.027 | 15.787 | 0.498*** | 0.03 | 16.81 | 0.269*** | 0.027 | 9.934 |

| Environmental Satisfaction | 0.302*** | 0.021 | 14.537 | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.14 | 0.174 | 0.238 | ||||||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.137 | 0.172 | 0.235 | ||||||

| F | F (5, 1652) = 53.771, p = 0.000 | F (5, 1652) = 69.765, p = 0.000 | F (6, 1651) = 85.737, p = 0.000 | ||||||

Note: *p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001.

Moreover, the other three factors have significant differences in the results from the test of the interaction effect between generations and countries (Table 7), except for environmental satisfaction. As seen in Figure 3, the scores in Chinese questionnaires are generally high across all generational groups. The chart of social influence in Figure 3a shows that Generations Y and Z in the Chinese and European markets have significantly higher scores than the others, indicating that consumers in these two generations pay more attention to the SI of SC. Interestingly, in the chart on FIN in Figure 3b, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, Generation X had the highest scores for FIN in the European market, but in China, it was Generation Y. The scores on European SC behaviour in Figure 3c are similar. But in China the scores on SC behaviour are relatively flat, indicating little difference between generations.

FIGURE 3.

Generations and Chinese and European market interaction test [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To determine the accuracy of the differences between Chinese and European FIN and SC behaviours in the interaction effects, we analysed Chinese and European data separately with ANOVA. The results show that no significant difference in SC behaviour across Chinese generational groups (F = 0.492, p = 0.688 > 0.005) but a significant difference across European generational groups (F = 10.766, p = 0.000 < 0.001). Moreover, the results of the pairwise comparison of Chinese and European data separately are consistent with the results of the interaction effect based on the full dataset. That is, consumers with the highest score on FIN are in Generation X in European countries but in Generation Y in China.

4.2. Hypothesis testing based on Chinese data

Because the Chinese and European markets differ significantly in the four factors (see Table 7), we divide China and Europe into two separate databases. First, the Chinese data are used to test the model, and then the European data are used to test the hypotheses. Finally, we compare and discuss the model in both contexts.

4.2.1. Direct effects in Chinese data

After we control for variables such as age, generational group, education level, and income level, the linear regression analysis reveals that social influence has a positive impact on SC behaviour (b = 0.615, p < 0.001), which supporting H3 (R2 = 0.400, p < 0.001).

4.2.2. Mediating role of environmental satisfaction in Chinese data

We used PROCESS (Model 4) for SPSS developed by Hayes (2017) to assess the indirect effect (IE) of social influence on SC behaviour through environmental satisfaction (see Table 8). All the variables were standardised before the analysis. Based on 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias‐corrected confidence intervals (CI), the results display a significant indirect positive impact of social influence on SC behaviour through environmental satisfaction (see Table 8). Because the CI did not include zero, environmental satisfaction acts as a mediator in the model (Hayes, 2017), supporting H5. Appendix A1 displays the hierarchical regression results for Chinese data (Table 9).

TABLE 9.

Results of model 4 for mediating effect of environmental satisfaction based on Chinese data

| Total | Direct | Indirect | 95% BootCI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Influence= > Environmental Satisfaction= > Sustainable Consumption behaviour | 0.615 | 0.422 | 0.193 | 0.180–0.222 | 0.000 |

4.2.3. Moderating roles of financial prudence in Chinese data

To test the significance of the moderating effects, we used the PROCESS Model 59 by Hayes (2017) with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% CI to examine the moderating effects of FIN on all the relationships in the model in order to test H7a, H7b, and H7c. As seen in Table 10, the interaction between social influence and FIN on SC behaviour has a significant and negative effect (b = −0.031, p < 0.05), offering partial support for H7a. We use Johnson‐Neyman to further test H7a (Spiller et al., 2013). Figure 4 shows that the conditional effect of social influence on SC behaviour is statistically significant across the entire range of FIN. This means that the continuous process of FIN has no point at which the conditional effect shifts from statistically significant to insignificant (Spiller et al., 2013). Thus, H7a is supported, indicating that, regardless of the level of FIN, social influence has a positive impact on SC behaviour. The figure also shows that the positive effect of social influence on SC behaviour is higher when FIN is lower. The moderating effect is illustrated in a diagram in Appendix A2.

TABLE 10.

Results of model 59 for moderation effects of financial prudence based on Chinese data

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | Environmental satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Constant | 0.069 | 0.085 | 0.810 | −0.45*** | 0.108 | −4.177 |

| Social influence | 0.317*** | 0.020 | 16.188 | 0.357*** | 0.024 | 15.082 |

| Financial prudence | 0.221*** | 0.018 | 12.179 | 0.255*** | 0.022 | 11.353 |

| Social influence* financial prudence | −0.031* | 0.015 | −2.023 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.256 |

| Gender | 0.048 | 0.027 | 1.736 | 0.271 | 0.034*** | 7.866 |

| Generations | −0.041* | 0.017 | −2.445 | −0.058 | 0.021** | −2.708 |

| Education level | 0.013 | 0.018 | 0.715 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.835 |

| Income level | 0.032 | 0.018 | 1.817 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 1.032 |

| Environmental satisfaction | 0.315*** | 0.017 | 18.088 | |||

| Environmental satisfaction* financial prudence | −0.012 | 0.019 | −0.630 | |||

| Sample size | 2113.000 | 2113.000 | ||||

| R 2 | 0.539 | 0.320 | ||||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.537 | 0.318 | ||||

| F | F (9, 2103) = 273.227, p = 0.000 | F (7, 2105) = 141.630, p = 0.000 | ||||

Note: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001.

FIGURE 4.

Conditional effect of social influence on sustainable consumption behaviour as a function of financial prudence based on Chinese data

The results in Table 10 also show the interaction effect of social influence and FIN for environmental satisfaction (b = 0.04, p > 0.05), rejecting H7b. In the same way, H7c is not supported by the results. This insignificant support for H7b suggests that the positive impact of social influence on environmental satisfaction does not increase when FIN is lower. The insignificant support for H7c indicates that the relationship between environmental satisfaction and SC behaviour is not affected, regardless of the level of FIN.

4.3. Hypothesis testing based on European data and comparative analysis

Based on European data, this paper uses the same method to test the hypotheses.

4.3.1. Direct effects in European data

After we control for variables such as age, generational group, education level, and income level, the linear regression analysis reveals that social influence has a positive impact on SC behaviour (b = 0.420, p < 0.001), supporting H3.

4.3.2. Mediating role of environmental satisfaction in European data

The results displayed in Table 11 indicate a significant, indirect, and positive impact of social influence on SC behaviour through environmental satisfaction. The CI also supports H5. Appendix A3 presents the hierarchical regression results of the European data (Table 12).

TABLE 12.

Results of model 4 for mediating effect of environmental satisfaction based on European data

| Total | Direct | Indirect | 95% boot CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Influence= > environmental Satisfaction= > sustainable consumption behaviour | 0.420 | 0.269 | 0.151 | 0.108 ~ 0.157 | 0.000 |

4.3.3. Moderating roles of financial prudence in European data

Table 13 shows the interaction between social influence and FIN on environmental satisfaction and SC behaviour and the interaction between FIN and environmental satisfaction on SC behaviour. The results partially support H7b (b = −0.091, p < 0.01), but not H7a and H7c. Figure 5 further supports H7b, indicating that social influence has a positive impact on environmental satisfaction, regardless of the level of FIN. The figure also shows that the positive effect of social influence on environmental satisfaction is higher when FIN is lower. The moderating effect is illustrated in a diagram in Appendix A4.

TABLE 13.

Results of model 59 for moderation effects of financial prudence based on European data

| Sustainable consumption behaviour | Environmental satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Constant | 0.002 | 0.150 | 0.014 | −0.365* | 0.165 | −2.209 |

| Social Influence | 0.117*** | 0.029 | 4.052 | 0.316*** | 0.031 | 10.265 |

| Financial Prudence | 0.156*** | 0.031 | 5.062 | 0.312*** | 0.032 | 9.607 |

| Social Influence* Financial Prudence | −0.011 | 0.027 | −0.401 | −0.091** | 0.028 | −3.241 |

| Gender | −0.007 | 0.045 | −0.147 | 0.276*** | 0.049 | 5.672 |

| Generations | −0.103*** | 0.024 | −4.304 | −0.032 | 0.026 | −1.232 |

| Education level | 0.039 | 0.025 | 1.602 | 0.114*** | 0.027 | 4.245 |

| Income level | 0.034 | 0.031 | 1.104 | −0.025 | 0.034 | −0.729 |

| Environmental Satisfaction | 0.372*** | 0.027 | 13.598 | |||

| Environmental Satisfaction * Financial Prudence | −0.042 | 0.022 | −1.881 | |||

| Sample size | 1658 | 1658 | ||||

| R 2 | 0.328 | 0.273 | ||||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.324 | 0.269 | ||||

| F | F (9, 1648) = 89.364, p = 0.000 | F (7, 1650) = 88.366, p = 0.000 | ||||

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

FIGURE 5.

Conditional effect of social influence on environmental satisfaction as a function of financial prudence based on European data

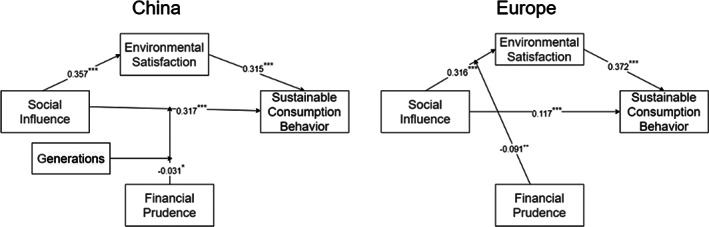

Comparative analysis

A comparison of the Chinese and European data in the model found the same results, except for the moderating effect of FIN. In the results with Chinese data, FIN has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour. In the analysis of European data, FIN has a moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and environmental satisfaction.

4.3.4. Moderating effect of generations with a Three‐Way interaction

The results in Section 4.1 demonstrate generational differences in FIN behaviours between Chinese and European consumers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Indeed, the group with the highest scores on FIN is Generation Y in the Chinese market and Generation X in the European market. Therefore, we further explore and analyse whether generational differences have a moderating effect on FIN in the model (H8).

Because generation is a categorical variable, SCwe used PROCESS Model 12, which allows probing interactions between multicategorical and continuous variables using multiple contrasts (Hayes, 2017). We entered generations as the multi‐categorical moderated moderation variable (baby boom = 1, Generation X = 2, Generation Y = 3, Generation Z = 4), and the baby boom group is the reference group. As shown in Table 14, the three‐way interaction of social influence, FIN behaviour, and three generations (in boldface in the table) is statistically significant, and the confidence interval does not include zero. Further, we analyse the moderating effects of the four generations in the high and low FIN behaviours (M ± 1SD), as shown in Table 15. Except for the baby boomer generation in the high FIN behaviours, which does not have a moderating effect, the rest of the generations have a moderating effect. Thus, H8 is partly supported. When FIN is low, the slope of the baby boom group is the highest among the four generations, but when FIN is high, Generation Z has the highest slope. This may be affected by intergenerational differences in social influence. At a high level of FIN, the moderating effect of Generation Z on FIN is better than that of other generations. At a low level of FIN, the baby boomers have a better moderating effect on FIN than the other generations.

TABLE 14.

Three‐way interaction effects of intergenerational differences

| Coefficient | SE | t | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.138 | 0.101 | 1.364 | −0.061 | 0.337 |

| Social influence | 0.332** | 0.083 | 3.979 | 0.168 | 0.495 |

| Financial prudence | 0.210 | 0.083 | 2.539 | 0.048 | 0.371 |

| Social influence* financial prudence | −0.148*** | 0.041 | −3.602 | −0.228 | −0.067 |

| Generation X | −0.118 | 0.087 | −1.355 | −0.289 | 0.053 |

| Generation Y | −0.232** | 0.084 | −2.759 | −0.397 | −0.067 |

| Generation Z | −0.243** | 0.085 | −2.840 | −0.410 | −0.075 |

| Social influence* Generation X | −0.002 | 0.092 | −0.025 | −0.182 | 0.178 |

| Social influence* Generation Y | −0.016 | 0.088 | −0.182 | −0.188 | 0.156 |

| Social influence* Generation Z | −0.024 | 0.091 | −0.264 | −0.201 | 0.154 |

| Financial prudence* Generation X | −0.050 | 0.090 | −0.561 | −0.227 | 0.126 |

| Financial prudence* Generation Y | 0.025 | 0.087 | 0.284 | −0.145 | 0.195 |

| Financial prudence* Generation Z | 0.024 | 0.090 | 0.265 | −0.152 | 0.200 |

| Social influence* financial prudence *X | 0.103 * | 0.049 | 2.094 | 0.007 | 0.199 |

| Social influence* financial prudence *Y | 0.113 * | 0.045 | 2.535 | 0.026 | 0.201 |

| Social influence* financial prudence *Z | 0.144 ** | 0.049 | 2.914 | 0.047 | 0.241 |

| Gender | 0.054 | 0.028 | 1.973 | 0.000 | 0.109 |

| Education level | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.742 | −0.023 | 0.050 |

| Income level | 0.029 | 0.018 | 1.590 | −0.007 | 0.065 |

| Environmental satisfaction | 0.313*** | 0.017 | 18.224 | 0.279 | 0.347 |

Note: The dependent variable is sustainable consumption behaviour. The part of the result where the dependent variable is environmental satisfaction is not statistically significant, so it is not shown.

TABLE 15.

The moderating effect of intergenerational differences on financial prudence

| Financial prudence | Generations | Coefficient | SE | t | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Baby boomers | 0.440 | 0.088 | 5.002 | 0.268 | 0.613 |

| Generation X | 0.363 | 0.047 | 7.657 | 0.270 | 0.455 | |

| Generation Y | 0.341 | 0.033 | 10.334 | 0.276 | 0.406 | |

| Generation Z | 0.311 | 0.045 | 6.977 | 0.223 | 0.398 | |

| High | Baby boomers | 0.119 | 0.103 | 1.153 | −0.083 | 0.321 |

| Generation X | 0.264 | 0.050 | 5.298 | 0.167 | 0.362 | |

| Generation Y | 0.266 | 0.036 | 7.337 | 0.195 | 0.337 | |

| Generation Z | 0.302 | 0.049 | 6.231 | 0.207 | 0.398 |

5. DISCUSSION

Prior research indicates that the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic varies from country to country (Gopinath, 2020), thus affecting consumption behaviour to various extents (Li et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2020). Unlike most existing studies, which analyse data from one or two countries (Grinstein & Riefler, 2015; Joshi & Rahman, 2017; Lazaric et al., 2019; Van Doorn & Verhoef, 2011; Vassallo et al., 2016; Yuesti et al., 2020), this article compares the changes in sustainable consumer behaviour during the epidemic in two influential markets including 13 countries.

The Covid‐19 pandemics has significantly altered the priorities of consumers (Vautier, 2020). More than 50% of millennials and nearly 50% of generation Z are saving money in order to deal with unexpected expenses (Deloitte, 2020). These results share commonalities with the findings of this research according to which in China, Generation Y and Generation Z are more cautious about finances than Generation X. In Europe, Generation Z is also more concerned about finances than other generations. Similarly, Lofts (2020) from Ernst & Young found that Covid‐19 pandemic is going to change consumer attitudes to sustainable finance towards a greener future. According to this survey, 50% of consumers still expect their lives to change significantly in the long‐term, while 53% say the pandemic experience has led to a re‐evaluation of their values and how they look at life. Moreover, financial sustainability is becoming a priority for 30% of consumers, while 26% of consumers rather focus on health and safety products. In our research results, we also found that in both the Chinese and European markets, when measuring FIN, there are more than half of people in each market who agree with the question of “I think much more than before when spending money”.

According to Leruste (2020) from multinational services company Accenture, 31% of US consumers preferred companies that were taking steps to reduce global warming and 21% avoided products of companies for opposing climate action. Research company Nielsen revealed in 2019 that 73% of global consumers would definitely or probably change their consumption habits in order to decrease their impact on the environment and 41% of consumers would pay premiums for all‐ natural or organic ingredients. Deloitte's survey in 2020 revealed that Millennials are more green‐orientated than Zoomers. Baby boomers, Generation X, Y and Z slightly differ in their attitude towards “clean” products, environmental responsibility, health and wellness benefits, recycling, and organic ingredients. While Boomers focus on “clean” environmentally friendly products, Generation Z prefers health and wellness benefits (Haller et al., 2020). In resonance to these studies from consulting firms, our research further provides academic evidence that, compared to the Generation X, Generation Y and Generation Z pay more attention to the social influence of SC.

Deloitte's survey shows that the pandemic has increased empathy and enthusiasm a positive of Millennials and Zoomers towards social aspects of life (carrying for myself, community, and others) (Deloitte, 2020). Moreover, it states that many companies declared that Covid‐19 changed consumer behaviours and consumers, at least temporarily, changed their preferences. More specifically, according to our finding, more than half of the respondents “prefer to pay extra for products produced in a sustainable way”, thus changing their consumer behaviour during the Covid‐19 epidemic as they started to focus more on products with environmentally friendly packaging.

In this context, the study first explores the differences in the Chinese and European markets and the interaction of generations and market in terms of social influence, SC behaviour, environmental satisfaction, and FIN. The study finds that significant differences arise between Chinese and European consumers regarding the four factors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This seems to contradict a recent study on the Brazilian and Portugese markets, which shows no difference in the impact of COVID‐19 on SC (Severo et al., 2021). Like other studies (Qi et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020), this study finds that the impact of COVID‐19 on SC differed among generations. Using multiple factors, we find that the intergenerational differences were significant only for social influence and SC behaviour. Indeed, Generations Y and Z pay more attention to social influence (Taylor et al., 2011) and SC behaviour (Bedard & Tolmie, 2018; Heo & Muralidharan, 2019) than other generations. Prior research on COVID‐19 and consumer behaviour discusses the differences between generations (Eger et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2021; Severo et al., 2021) and markets (Islam et al., 2021; Keane & Neal, 2021), but few discuss the effects of markets and generations on SC (Severo et al., 2021). For instance, according to the global study by Deloitte (2020), Generations Y and Z both score high on FIN, and COVID‐19 did not affect their buying behaviour. We found that Generation X in Europe and Generation Y in China had the highest FIN during the epidemic. In addition, although SC behaviour by Chinese consumers was not significantly affected by intergenerational differences, in the European market SC behaviour by Generation X was significantly affected in comparison to other generational groups.

Second, the results further confirm that, during the epidemic, the influence of social interaction promotes SC behaviour and social influence motivates users to engage in SC behaviour by enhancing environmental satisfaction. Thus, this result confirms the importance of influencers in raising awareness of SC, especially Generation Y consumers (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018). Moreover, the research finds that social influence can further influence SC behaviour by improving environmental satisfaction. This provides new evidence on a shift from environmental awareness to actual SC behaviour (Wang & Tou, 2021).

Third, previous studies document the economic impact of pandemics (Bell & Lewis, 2005). Some studies claim that uncertainty caused by an epidemic and disease prevention protocols led to a lower level of sustainable behaviour (van der Wal et al., 2018). The pandemics also engendered fluctuations in global economic and political conditions, which might affect consumers' degree of FIN (Coibion et al., 2020; Deloitte, 2020; Noordegraaf‐Eelens & Franses, 2014), especially during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In the multifactorial analysis of the Chinese data, we found that FIN has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour. Thus, the influence of social influence on SC behaviour is gradually weakened by an increase in FIN behaviour. However, FIN has no significant moderating effect between social influence and environmental satisfaction or between environmental satisfaction and SC behaviour. Therefore, it is of great significance to influence SC behaviour through social influence on environmental satisfaction. Nevertheless, the results show that the impact of social influence on SC behaviour through environmental satisfaction in the European market is not affected by FIN.

The moderating effect of FIN occurs in the relationship between social influence and environmental satisfaction—that is, the higher the degree of FIN, the weaker the effect of social influence on environmental satisfaction. Our results further show that, among European consumers, FIN does not affect SC behaviour in the presence of high environmental satisfaction. By introducing variables for FIN and environmental satisfaction into the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour, we contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between social influence and SC behaviour (Bakar et al., 2020; Alekam, 2018; Ivan & Dickson, 2008).

The verification results of the main effect and the mediating effect are similar for the Chinese and European markets. However, differences emerge in the moderating effect of FIN. Based on differences in the four factors across markets, the group with higher FIN seems to be Generation Y in the Chinese market but Generation X in the European market. Our study of Chinese data shows that intergenerational differences in China have a moderating effect on FIN, but we could not confirm the moderating effect of intergenerational differences on FIN in the European market. Figure 6 compares the hypothetical models across markets.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of Chinese and European hypothesis model testing

6. CONCLUSIONS